Symbolic Beauty in Design and Structure

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Symbolic Beauty in Design and Structure," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 71–90.

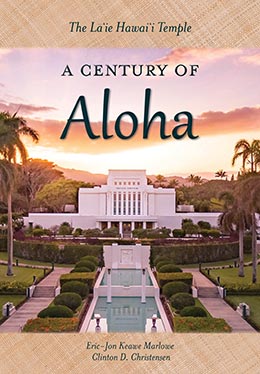

Even without its many forthcoming adornments, the temple’s design and structure alone was both symbolic and striking. Painting by LeConte Stewart. Courtesy of the Church History Museum, Salt Lake City,Utah.

Even without its many forthcoming adornments, the temple’s design and structure alone was both symbolic and striking. Painting by LeConte Stewart. Courtesy of the Church History Museum, Salt Lake City,Utah.

With unanimous approval for a temple in Hawaiʻi, President Joseph F. Smith concluded his conference remarks saying, “We shall now proceed, as circumstances and means will permit.”[1] It would seem precarious to attempt to erect a temple in the midst of World War I (1914–18), yet Hawaiʻi’s location, nearly half a world away from the main conflict, mitigated the effects of those events. What’s more, during this era sugarcane prices were relatively strong and consistent, enabling the Lāʻie Plantation to generate a steady stream of revenue needed for building the temple.[2]

Architectural Design

Facilitating a rather prompt start to the temple’s construction was the fact that Church leaders decided to use an architectural design similar to that used for the temple in Alberta. This meant modification of an existing plan rather than a full-scale proposal and decision process that could easily have taken several more months.[3]

Selecting the design

The design of the Alberta Temple had been determined through a competition. The Presiding Bishopric invited fourteen Latter-day Saint architects to anonymously (to ensure fair judging) submit designs based on only a few criteria. The criteria included the necessary ordinance rooms, the specified size, and the request that the drawings situate the temple “on an eminence facing the east.”[4] But perhaps more interesting was what the criteria omitted or indicated was not requisite. Most notable was the removal of the large assembly halls that had been a significant feature in all preceding temples. What’s more, the Presiding Bishopric suggested that towers need not form any important symbolic feature of the plan, and no direction on any particular style of building was provided.[5] Lastly, although it is unclear how much emphasis would be placed on construction cost, cost would be a factor in the decision process.[6]

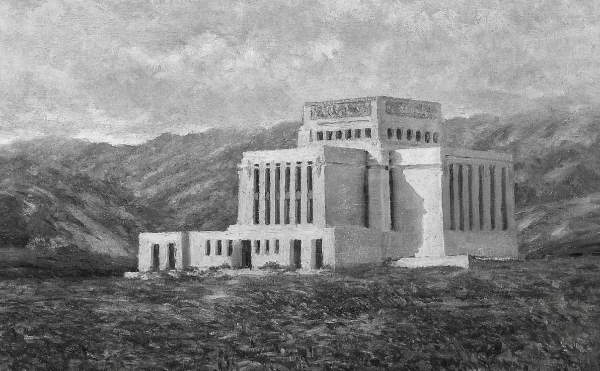

The Laie Hawaii Temple combined ancient and modern design, drawing from such structures as the ancient temple in Jerusalem, pre-Columbian ruins in America, and contemporary

The Laie Hawaii Temple combined ancient and modern design, drawing from such structures as the ancient temple in Jerusalem, pre-Columbian ruins in America, and contemporary

buildings such as Frank Lloyd Wright’s Unity Temple in Chicago, Illinois. Sketch of Laie Hawaii Temple courtesy of Church History Library.

Seven architectural designs were eventually submitted and put on public display in the Bishop’s Building in downtown Salt Lake City.[7] Noticeably, most of the designs submitted incorporated towers and pinnacles, in some ways resembling the familiar Salt Lake Temple.[8] However, the First Presidency bypassed the more traditional plans in favor of what has been called a “daringly modern design.”[9] The winning proposal came from the architectural firm of Pope and Burton, which at the time had been in business less than three years. Hyrum C. Pope, a German immigrant in his early thirties, was the firm’s engineer and manager. Harold W. Burton, the designer and junior partner, was twenty-five.[10]

Of the original design of the Alberta Temple, Hyrum Pope later explained that it occurred to him and Burton that the temple should be “in harmony with the genius of the Gospel which has been restored. . . . It should be ancient as well as modern, it should express all the power which we associate with God.”[11] To produce this “ancient as well as modern” design, Pope and Burton drew on their training. Both men were among the earliest admirers of modern American architect Frank Lloyd Wright, and Burton had studied the pre-Columbian ruins of Mexico and Central America.[12] It appears that consideration was also given to the ancient Israelite temple of Solomon.[13]

Ancient temple in Jerusalem. Courtesy of Deror avi, Wikimedia Commons.

Ancient temple in Jerusalem. Courtesy of Deror avi, Wikimedia Commons.

Mayan ruins at Tulum, Mexico. Photo by Dennis Jarvis. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://

Mayan ruins at Tulum, Mexico. Photo by Dennis Jarvis. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://

When it was decided to build a temple in Hawaiʻi two years later, Church leadership again looked to Pope and Burton as architects, asking them to design a similar but smaller version of the Alberta Temple for the temple site in Lāʻie. Latter-day Saint architectural historian Paul L. Anderson observed, “In its architectural style, the Hawaii Temple reflected many of the same influences as the Alberta design. It bore a strong resemblance to Wright’s Unitarian Church with its rectilinear form and flat roofs. More than the Alberta Temple, the Hawaii Temple also borrowed rather literally from elements of pre-Columbian American architecture. Perhaps traditional Book of Mormon connections with Polynesia reinforced the appropriateness of this borrowing.”[14] Anderson concluded that the combination of these influences in the temple design was unquestionably in the forefront of American architecture at that time. Ultimately the architects did much more than create a miniature of the Alberta Temple. The dimensions, mode of construction, materials, art, landscaping, terraced pools, and other factors involved in the Hawaii Temple’s construction would render an edifice that is distinct from any other temple in the Church.[15]

Interior design reflects a change in focus

Unity Temple in Chicago, Illinois. Photo by Brian Crawford. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://

Unity Temple in Chicago, Illinois. Photo by Brian Crawford. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, https://

For the Church’s temples, this shift in design from that of the Salt Lake and earlier temples to that of the Alberta and Hawaii Temples likely remains the most pronounced design change of this dispensation. All previous Latter-day Saint temples had been “meetinghouse temples,” generally composed of “large meeting rooms one above the other.” However, in the late 1870s there was a major change in the interior arrangement of temples after Church leaders decided to replace the two lower assembly rooms with ordinance rooms for the presentation of the endowment.[16] Omitting the large halls marked a complete transition from a multipurpose temple design to temples with a singular focus on ordinances that continues today.

Consequently, the elimination of the large assembly room left the design focus squarely on the four major ordinance rooms and the celestial room, allowing their arrangement to shape the entire building. “As designer Harold Burton pondered this situation,” wrote Anderson, “he arrived at a brilliant architectural composition that was perfectly logical and simple. The four ordinance rooms would be arranged around the center like the spokes of a wheel, each one a few steps higher than the one before, with the celestial room in the center at the very top of the building. The baptismal font would be in the center of the lower level directly below the celestial room.”[17] This arrangement was both practical and symbolic. As people pass through all four ordinance rooms, they do so in an ascending spiral to the central celestial room, which occupies the highest space in the temple. Such architectural arrangement elegantly portrays the idea of progression found in the temple endowment ceremony itself.[18]

Symbolism of the exterior design

South side view of the Laie Hawaii Temple. Patrons enter the ground level of the temple from the east side. Then in ascending symbolism they pass from room to room until reaching the celestial room, the pinnacle of the temple. Courtesy of Church History Library.

South side view of the Laie Hawaii Temple. Patrons enter the ground level of the temple from the east side. Then in ascending symbolism they pass from room to room until reaching the celestial room, the pinnacle of the temple. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Because there was no “pre-conceived idea of [the temple’s] external outline,” the principal rooms inside influenced the most prominent features outside.[19] The four ordinance rooms, each pointing in a cardinal direction, form a symmetric cross with an entrance extending to the east. At the center, projected above it all, is the celestial room, providing a suggestion of a tower.[20] The unity of interior and exterior, a basic principle of modern architecture,[21] provided a simple yet striking exterior in need of little embellishment.

The outside design and orientation of the temple are also symbolic. The shape of the Hawaii Temple is a Greek cross,[22] a design widely used in Byzantine architecture and later imitated in some Western churches.[23] In Christianity a cross generally represents Christ’s sacrifice or is emblematic of Christianity itself. However, a Greek cross, with four arms of the same length, was intended to represent not necessarily the Crucifixion, but rather the four directions of the earth and the spread of the gospel thereto.[24] “And he shall set up an ensign for the nations,” Isaiah said, “and gather together the dispersed . . . from the four corners of the earth” (Isaiah 11:12). This symbolism of evangelism and gathering in the temple’s structure seems particularly symbolic when considering these words from the Prophet Joseph Smith: “What was the object of gathering the . . . people of God in any age of the world? . . . The main object was to build unto the Lord a house whereby He could reveal unto His people the ordinances of His house and the glories of His kingdom, and teach the people the way of salvation.”[25]

Furthermore, the ancient Israelites built their temple with the main doors facing east. The rising of the sun announced the new day, symbolizing new beginnings and opportunities.[26] Ezekiel wrote that “the glory of the God of Israel came from the way of the east. . . . And the glory of the Lord came into the house [temple] by the way of the gate whose prospect is toward the east” (Ezekiel 43:1–4). In like manner, five of the first six Latter-day Saint temples built in this dispensation were deliberately constructed facing the east, the Hawaii Temple included.[27] Moreover, this eastward orientation symbolizes watching for the Second Coming of the Savior, an event likened to the dawning of a new day (see Joseph Smith—Matthew 1:26).[28]

What the design omits

The temple forms the shape of a Greek cross (four sides of equal length), which can symbolize gathering “together the dispersed . . . from the four corners of the earth” (Isaiah 11:12). Courtesy of Church History Library.

The temple forms the shape of a Greek cross (four sides of equal length), which can symbolize gathering “together the dispersed . . . from the four corners of the earth” (Isaiah 11:12). Courtesy of Church History Library.

The design of the Hawaii Temple is also recognizable for what it does not share with most other Latter-day Saint temples, specifically spires and an angel Moroni. As stated earlier, the criteria given the architects by Church leaders did not indicate the necessity of spires. This omission likely involved some consideration of cost and undue encumbrance. The architects also noted that the biblical temple of Solomon, and the ancient American temples they studied, did not use spires. As for the angel Moroni, of the four temples in operation before the Hawaii Temple, only one, the Salt Lake Temple, included a statue of the angel Moroni. Although the angel is beautifully symbolic, at the time of the Hawaii Temple’s construction it was not considered necessary and was several decades away from becoming a symbol synonymous with temples.[29]

Perhaps one more feature absent in the design needs mention—size. When originally constructed, the Hawaii Temple was just over ten thousand square feet. That was at least ten times smaller than any other temple in operation at the time and well over twenty times smaller than its predecessor, the Salt Lake Temple. Although the Hawaii Temple is so small in comparison, the architects’ exacting focus on the ordinances allows the temple to accommodate approximately fifty patrons per session, which is only four times fewer than what the Salt Lake Temple can accommodate, which is approximately two hundred patrons. The Salt Lake Temple was built with multiple purposes in mind; however, if it had the same ratio of patron to square footage as that of the Hawaii Temple, it would accommodate well over a thousand patrons per endowment session. Such efficiency of scale was another genius of Pope and Burton’s design.

Hyrum Pope said of the completed design, “Both in exterior treatment and interior arrangement, it is a highly symbolical expression of the sacred purpose of the edifice.” He then added, “Truth and simplicity have been the guiding stars in every detail of the design.”[30] When more than fifty years later Harold Burton was asked what he would change if he were to design the Hawaii Temple today, he responded, “I was twenty-nine years old when I designed that. With all the experience I’ve had, I couldn’t add one thing to that building. Not one thing. I was inspired, pure inspiration, that was way over my head.”[31]

Labor

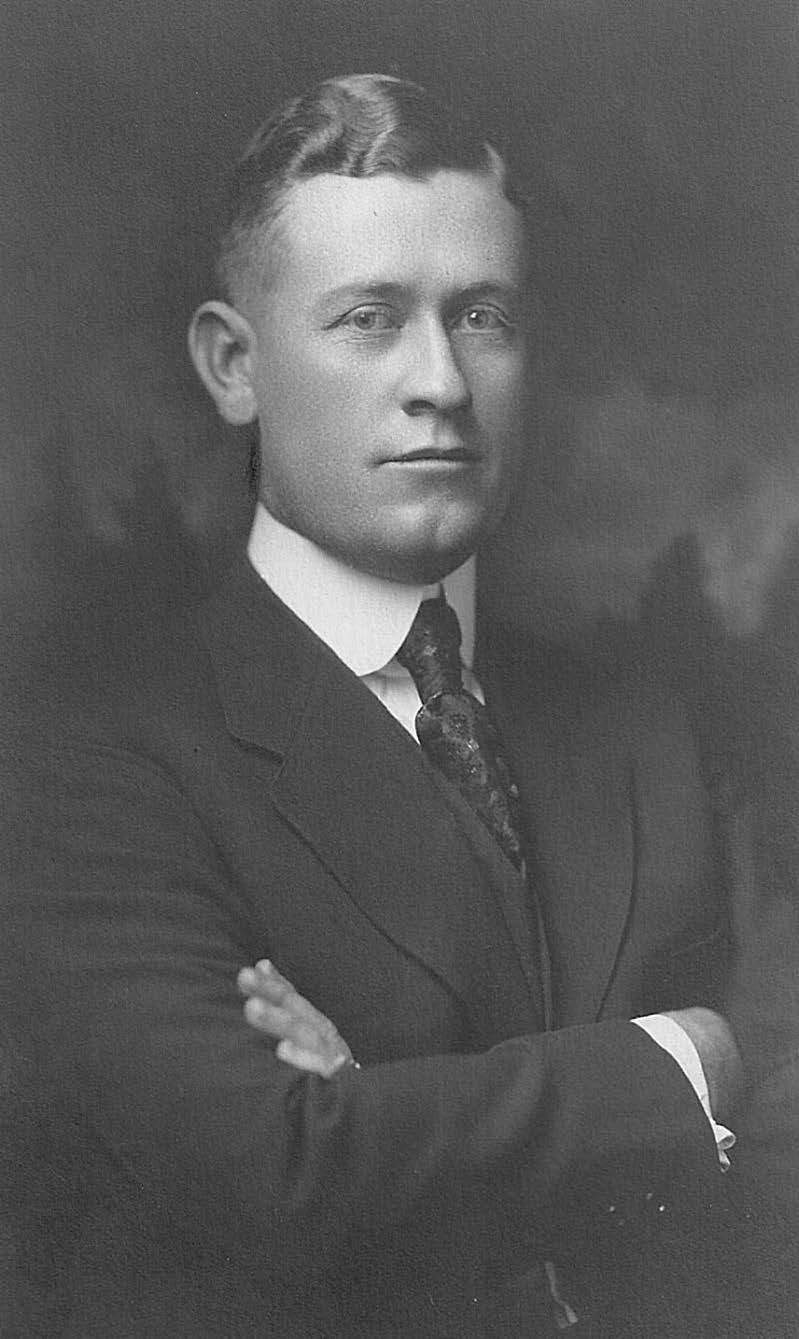

Ralph E. Woolley filled the role of general contractor and played an important role in the temple’s construction from start to finish. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii

Ralph E. Woolley filled the role of general contractor and played an important role in the temple’s construction from start to finish. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii

Archives.

Overall construction proceeded under the supervision of President Samuel E. Woolley. During construction Woolley continued as mission president, the highest ecclesiastical leader in Hawaiʻi, and as plantation manager. With these responsibilities, President Woolley was not constantly on the job site. However, he regularly observed construction, was involved in most major decisions, coordinated efforts with the Presiding Bishop’s Office, and brought invaluable experience, connections, and leadership to the process. A particularly important role President Woolley handled during construction was that of financier. Although money was at times advanced through the Presiding Bishop’s Office in Salt Lake City, the temple was largely, if not completely, funded by plantation earnings and by the tithing and other donations of Church members in Hawaiʻi—all of which were ultimately accounted for by President Woolley.

Ralph E. Woolley (age twenty-nine), President Woolley’s son, filled the role of project manager, or what today might be best described as general contractor. The temple was his full-time focus for nearly three years. Although Ralph was inexperienced in some aspects of building the temple, his work repeatedly demonstrated his acumen and resourcefulness. Of Ralph’s role in building the temple, Hyrum Pope averred, “A description of the Hawaiian temple would be incomplete without calling attention to the painstaking labors of Mr. Ralph E. Woolley, who had charge of the construction work, from commencement to completion.”[32]

There was also a cadre of invaluable professionals who contributed immensely to the temple’s construction and beauty. Architects Pope and Burton were joined by the Spalding Construction Company; muralists such as Lewis A. Ramsey, LeConte Stewart, and Alma B. Wright; sculptors J. Leo and Avard Fairbanks; and other specialized workers.

Yet by far those most responsible—in time, effort, and sacrifice—for the construction of the temple were the Hawaiian members themselves. Local men like Hamana Kalili and David Haili were exceptional foremen. And capable local men such as Edward Aki Forsythe, Ulei, Kaleohano Kalili, Keawemauhili Jr., Henry Nawahine, Kaeonui, Keanoa, Kema Kahawaii, Imaikalani, and Papa H. Kaio made up a crew that generally worked ten-hour days, six days a week, earning $1.25 per day.[33] The Relief Society sisters prepared meals for the workers, and children took the food to the temple site daily.[34] In addition to tithing, members throughout the islands personally donated at great sacrifice what they could to the temple fund. Members also organized musical performances, dances, and lūʻaus, often going house to house selling tickets to raise money for the temple.[35] Such labor, effort, and sacrifice of the Hawaiian members would continue throughout the construction years and contribute immeasurably to the temple’s construction.

Moving the Chapel

With the completed architectural plans in hand, Hyrum Pope, accompanied by President Samuel Woolley, traveled to Lāʻie to initiate the temple’s construction. There was a lot to consider upon their arrival in late December 1915.[36] Foremost, the location designated by President Joseph F. Smith for the temple was occupied by the I Hemolele Chapel, then possibly the largest structure on the windward side of Oʻahu at thirty-five feet by sixty-five feet, holding up to seven hundred people.[37] Before any construction could begin, the chapel would need to be removed.

Rather than dismantle the chapel, a plan was devised to move it to a new location, and work toward that goal began on 16 January 1916.[38] A new site for the chapel was readied down the hill and to the northeast, and the chapel itself was lifted off its foundation with jacks. Large timbers were then placed underneath the chapel, providing a relatively sturdy and flat surface upon which two rows of four-inch pipe about three feet long were laid under either side of the building. When the building was lowered onto the pipes, men with tackles and long ropes were able to pull and push the building down the hill. Each time the building rolled off the pipes, they were carried ahead and placed on solid timber so the chapel could again roll over them, thereby making a continuous track on which the chapel was hauled. It took several days to move the chapel and to set it up where it stood in use until 1941.[39] Moving the chapel was a remarkable feat of ingenuity, improvisation, and grit—emblematic of similar feats to come during the temple’s construction.

To make way for the temple, the chapel was lifted using jacks in preparation to roll it down the hill and then north to its new location. Courtesy of Church History Library.

To make way for the temple, the chapel was lifted using jacks in preparation to roll it down the hill and then north to its new location. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The Temple Structure

The foundation

With the temple site now cleared for construction, workers began excavating the ground for the temple foundation with picks, hand shovels, blasting powder, and a mule-driven scraper.[40] The excavation revealed coral rock with numerous pockets filled with soil.[41] This presented a worrisome challenge—how to design a satisfactory foundation for such a heavy structure on a porous rock formation.[42] To ensure a solid foundation, workers removed all the soil and loose coral, which in some instances required going ten to fifteen feet deep.[43] These cavernous trenches were then filled with a combination of large lava rocks and cement to form the thick and sure foundation upon which the temple could safely be built.[44]

Composition of the structure

Another major construction dilemma had been under consideration for months. All previous temples had been built from quarried stone, but the volcanic geology of Hawaiʻi could not provide such stone, and shipping it to the islands was too costly. Pope wrote, “It was quite a problem to determine the material of which it [the Hawaii Temple] should be built, for, although highly favored in other respects, the islands are almost devoid of building materials.”[45]

Apparently at one point the use of structural steel was considered.[46] However, after spending time in Hawaiʻi, Pope learned that lava rock “readily obtainable near the [temple] site could be crushed into an aggregate which would make very good concrete,” and he determined that the temple could be built of reinforced concrete.[47] “This was a very progressive building technique for the time, particularly in such a remote location. Frank Lloyd Wright had pioneered this system for his Unitarian Church in Chicago just ten years earlier.”[48]

Spalding Construction Company

Remarkably, in 1916 there was a company in Honolulu that specialized in this very type of concrete construction. Walter T. Spalding had earned an engineering degree from MIT with focus on reinforced concrete design, a rare profession in those days. After graduating in 1910, he worked for a year with the Hennebique Construction Company in New York, an innovative leader in reinforced concrete construction, before forming the Spalding Construction Company in Portland. When he won a construction bid from the US Navy, he moved his company to Honolulu in 1912.[49]

To ensure a solid foundation for the temple, workers dug cavernous trenches up to fifteen feet deep, filling them with a combination of large lava rocks and cement. The entire temple would be built without the use of heavy equipment. Courtesy of Church History Library.

To ensure a solid foundation for the temple, workers dug cavernous trenches up to fifteen feet deep, filling them with a combination of large lava rocks and cement. The entire temple would be built without the use of heavy equipment. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Most likely in February 1916, Pope approached Spalding with the temple plans, wanting to know the conditions under which he would consider constructing the building. Spalding, though not a Church member, offered to do so for cost plus a fee of 5 percent, cost being all expenses as shown by bills and receipts to be settled every month. Five percent was half the price Spalding charged for any other work he ever did on the islands.[50] Shortly thereafter President Smith and Bishop Nibley arrived in Hawaiʻi to follow up on the temple’s progress, and a special meeting was held in Lāʻie on 4 March 1916 to specifically consider entering into the contract with the Spalding Construction Company. The terms of the agreement were unanimously agreed upon, and afterward President Smith remarked, “I am mighty well pleased with this arrangement, for I must admit that it has been somewhat a worry to me, but now I feel perfectly easy about the matter. I feel that my trip has been a success now.”[51]

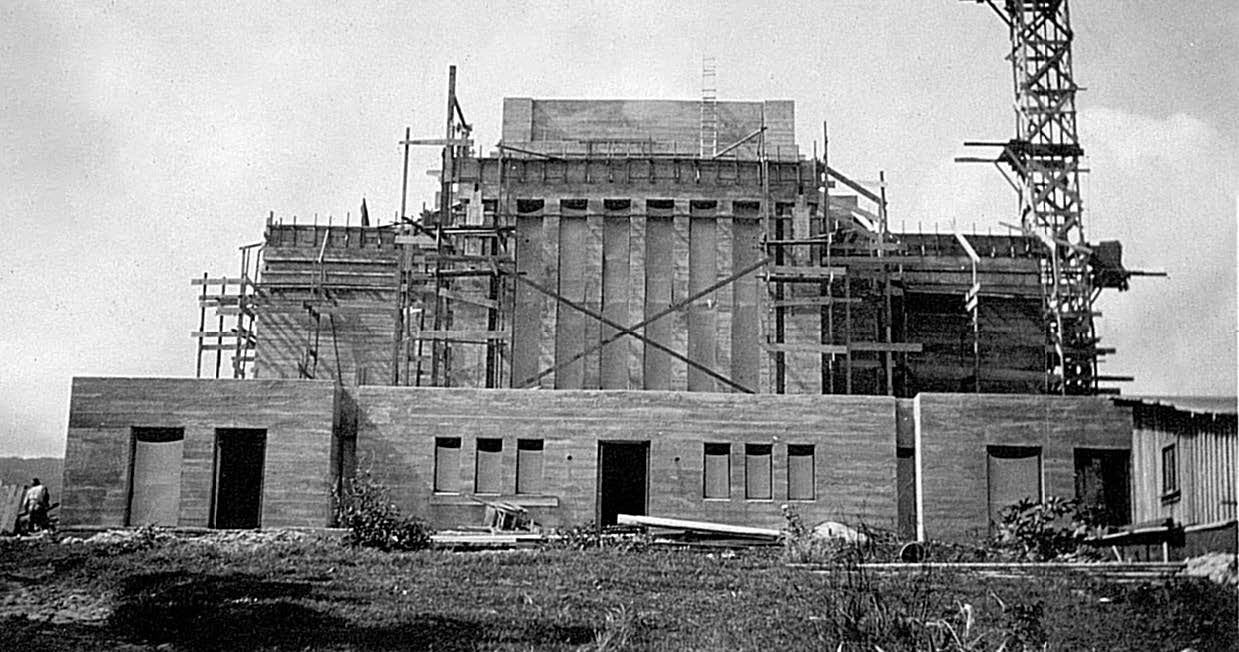

Temple under construction in 1916. Laborers on the temple site were mainly Native Hawaiian members. Courtesy of BYU–

Temple under construction in 1916. Laborers on the temple site were mainly Native Hawaiian members. Courtesy of BYU–

Hawaii Archives.

The work

Because the project was going to require such an enormous amount of cement, the decision was made to build and equip a factory for crushing lava rock and mixing cement on-site.[52] However, with the exception of crushed rock and sand, almost all other supplies needed to be transported by railroad from Honolulu around Kaʻena Point (a distance of more than seventy miles).

Lava rocks near the temple site were crushed and used to make the cement that forms the temple structure. Photo by Eric Marlowe.

Lava rocks near the temple site were crushed and used to make the cement that forms the temple structure. Photo by Eric Marlowe.

With the construction site cleared, footings in place, staging area prepared, and supplies on hand, the project moved into a higher gear. President Woolley arranged with Spalding to use mainly Native Hawaiian Church members on his crew. Spalding was skeptical at first, stating that “they were neither carpenters nor cement workers or plumbers or anything of that sort.” Yet he quickly observed that they “were great workers. Each one would try to outdo the other in handling crushed rock and other supplies. I don’t recall how long it took to do it, but it went forward at a . . . good rate.”[53]

April through October 1916

West side view of the temple under construction, with rock-crushing equipment

West side view of the temple under construction, with rock-crushing equipment

at left.

Satisfied that matters were in order and moving ahead, Hyrum Pope returned to Utah in April.[54] Later that same month, President Woolley established a business relationship with Theo H. Davies and Company of Honolulu for supplies and hardware that lasted throughout the temple’s construction.[55] Almost daily, forms were being set and cement poured. In the period of April through October 1916, the temple site went from dirt and footings to the temple in its basic stately form.[56] Though far from finished, the temple’s unadorned frame (bare floors, walls, and roof) was majestic and a marvel.

Front view of the temple under construction. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Front view of the temple under construction. Courtesy of Church History Library.

“The entire edifice, floors and roofs as well as the walls,” wrote Pope, were made “of cement concrete, reinforced with steel in all directions. Hence, the building is a monolith of artificial stone, which, after thoroughly hardening, has been dressed on all of its exterior surfaces by means of pneumatic stone cutting tools, thus producing a cream-white structure which may be literally said to be hewn out of a single stone.”[57] Special credit needs to be given to Walter T. Spalding and his company for their expertise and management of this crucial phase of the construction. In approximately seven months, in rural conditions, they built an innovative structure that has stood the test of time.

Such rapid progress led President Woolley and others to suggest that the temple could be ready for use by “spring or early summer 1917.”[58] However, framing a building is only part of a finished edifice—and for the Hawaii Temple the finish work necessary to achieve the beauty and quality that distinguishes a house of the Lord would require much more time and labor.

Notes

[1] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, 3 October 1915. See Millennial Star, 4 November 1915.

[2] See Jeanne Kuebler, “Sugar Prices and Supplies” and the subsection “Conditions in Sugar Market Before Depression,” Editorial Research Reports 2 (1963): 563–82, http://

[3] Further enabling a prompt start to the temple’s construction, almost one month before the temple’s public announcement “Ralph Wooley arrived at Laie to do engineering on the plantation and on the new temple.” See Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as History of the Hawaiian Mission), 7 August 1915.

[4] “Approved Design for Temple in Alberta Province: Pope & Burton Awarded First Honors in Architects’ Competition,” Deseret Semi-Weekly News, 2 January 1913.

[5] See “Approved Design.”

[6] “Church leaders, seeking to avoid needless expense, had recommended against large towers and spires. They also reiterated the decision that a large assembly room was no longer needed.” Paul L. Anderson, “A Jewel in the Gardens of Paradise: The Art and Architecture of the Hawaiʻi Temple,” BYU Studies 39, no. 4 (2000): 167. See Presiding Bishop’s Office, Presiding Bishopric journals, 1912, no. 4, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL), 26–27.

[7] See “Approved Design.”

[8] Harold W. Burton to Randolph W. Linehan, 20 May 1969, Harold W. Burton Papers, MS4235, folder 3, CHL. See Paul L. Anderson, “First of the Modern Temples,” Ensign, July 1977, 6–11.

[9] Anderson, “First of the Modern Temples,” 8.

[10] See Dorothy Ruth Pope Christensen, Hyrum C. Pope Papers, MS 16347, CHL; and Anderson, “First of the Modern Temples,” 6–11.

[11] Hyrum C. Pope Papers, Alberta Temple dedication, 29 August 1923, MS 16347, CHL.

[12] See Harold W. Burton to Randolph W. Linehan, 20 May 1969, Harold W. Burton Papers, CHL.

[13] See Hyrum C. Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” Improvement Era, December 1919.

[14] Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 170.

[15] See Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 170.

[16] See C. Mark Hamilton, The Salt Lake Temple: A Monument to a People (Salt Lake City: University Services, 1983), 54–55. See also Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 166. Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” notes that the large assembly rooms in the earlier temples took up “almost one-half of the entire structure” (p. 151).

[17] Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 168.

[18] See Anderson, “First of the Modern Temples, 6–11”; and Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 168.

[19] Harold W. Burton to Randolph W. Linehan, 20 May 1969, Harold W. Burton Papers, CHL.

[20] See Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii”; and Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 168.

[21] See Anderson, “First of the Modern Temples,” 6–11.

[22] Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” 151. See N. B. Lundwall, “The Hawaiian Temple,” chap. 7 in Temples of the Most High (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1941).

[23] Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, s.v. “Greek-cross plan,” https://

[24] “Greek Cross (Cross Imissa, Cross of Earth),” SymbolDictionary.net: A Visual Glossary, http://

[25] Quoted in Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph Smith (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2011), 416.

[26] See Richard O. Cowan, “Latter-day Saint Temples as Symbols,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 21, no. 1 (2012): 2–11, http://

[27] Shortly after the temples in Hawaiʻi and Alberta, Latter-day Saint temples began to face the direction most suitable to the building site. Also, BYU–Hawaii professor Mark James has noted that magnetic north and true north are about eleven degrees different in Hawaiʻi, and in the case of the Laie Hawaii Temple, it appears the builders used magnetic east.

[28] See Cowan, “Latter-day Saint Temples as Symbols.”

[29] After the Salt Lake Temple (1893), the next temple to receive a statue of the angel Moroni was the Los Angeles Temple sixty-three years later (1956). Over two decades later, the Washington DC Temple received the third statue of Moroni (1974). Not until the 1980s did these statues begin to adorn virtually all new temples. Over the years, a number of temples originally built without the statue of Moroni had them added to their towers. See Cowan, “Latter-day Saint Temples as Symbols”; see also “Angel Moroni Statues on LDS Temples,” https://

[30] Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” 151.

[31] Edward L. Clissold, interview by R. Lanier Britsch, 11 June 1976, PCC oral history, James Moyle Oral History Program, MSSH 261, box 2, CHL.

[32] Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” 152.

[33] See Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957, MSSH 284, box 52, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives).

[34] See Josephine Huddy, Laie Hawaii Temple Centennial Collection, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[35] See Dean Clark Ellis and Win Rosa, “‘God Hates a Quitter’: Elder Ford Clark: Diary of Labors in the Hawaiian Mission, 1917–1920 and 1925–1929,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 28, no. 1 (2007), https://

[36] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 22 December 1915.

[37] See Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2011), 40.

[38] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 12 January 1916.

[39] See Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957.

[40] See Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957. See also William R. Bradford, “My Memories of Lāʻie,” MS 30906, folder 93, CHL.

[41] See Rudger J. Clawson, “The Hawaiian Temple,” Millennial Star, 8 January 1920, 30–32.

[42] See Dorothy Ruth Pope Christensen, Hyrum C. Pope Papers, MS 16347, CHL.

[43] See Clawson, “Hawaiian Temple,” 31.

[44] See Hui Lau Lima News, temple edition, 24 November 1957. See also Marvel Murphy Young and Eva Newton, recorded interview with Kehau Peterson Kawahigashi in “Finishing the Hawaii Temple,” MSSH 496, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 331–40.

[45] See Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” 149.

[46] See Charles W. Nibley to Samuel Woolley, 17 December 1915, in Correspondence and Reports Relating to the Building of the Laie, Hawaii Temple, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[47] Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” 149.

[48] Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 168.

[49] Walter T. Spalding, interview by Max Moody, 28 May 1973, AV 2226, Spalding transcript, CHL.

[50] Spalding, interview.

[51] Quoted in History of the Hawaiian Mission, 4 March 1916, record C:1-36.

[52] See Clawson, “Hawaiian Temple”; and Spalding, interview.

[53] Spalding, interview.

[54] See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 11 April 1916.

[55] Samuel Woolley to Theo H. Davies, 24 April 1916, in Correspondence and Reports Relating to the Building of the Laie, Hawaii Temple.

[56] A report on progress as of October 1916 in Correspondence and Reports Relating to the Building of the Laie, Hawaii Temple notes, “All the walls and roofs poured. All forms stripped except interior of roof #5. Total concrete in place 1262.5 cu. Yds.”

[57] Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” 150–51.

[58] John A. Widtsoe, “The Temple in Hawaii: A Remarkable Fulfilment of Prophecy,” Improvement Era, September 1916, 956. See History of the Hawaiian Mission, 9 April 1916; and E. L. Miner, “The Hawaii Mission,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 30 May 1916, 778–80.