Sculptures, Murals, and Interior Finish

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Sculptures, Murals, and Interior Finish," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 91–108.

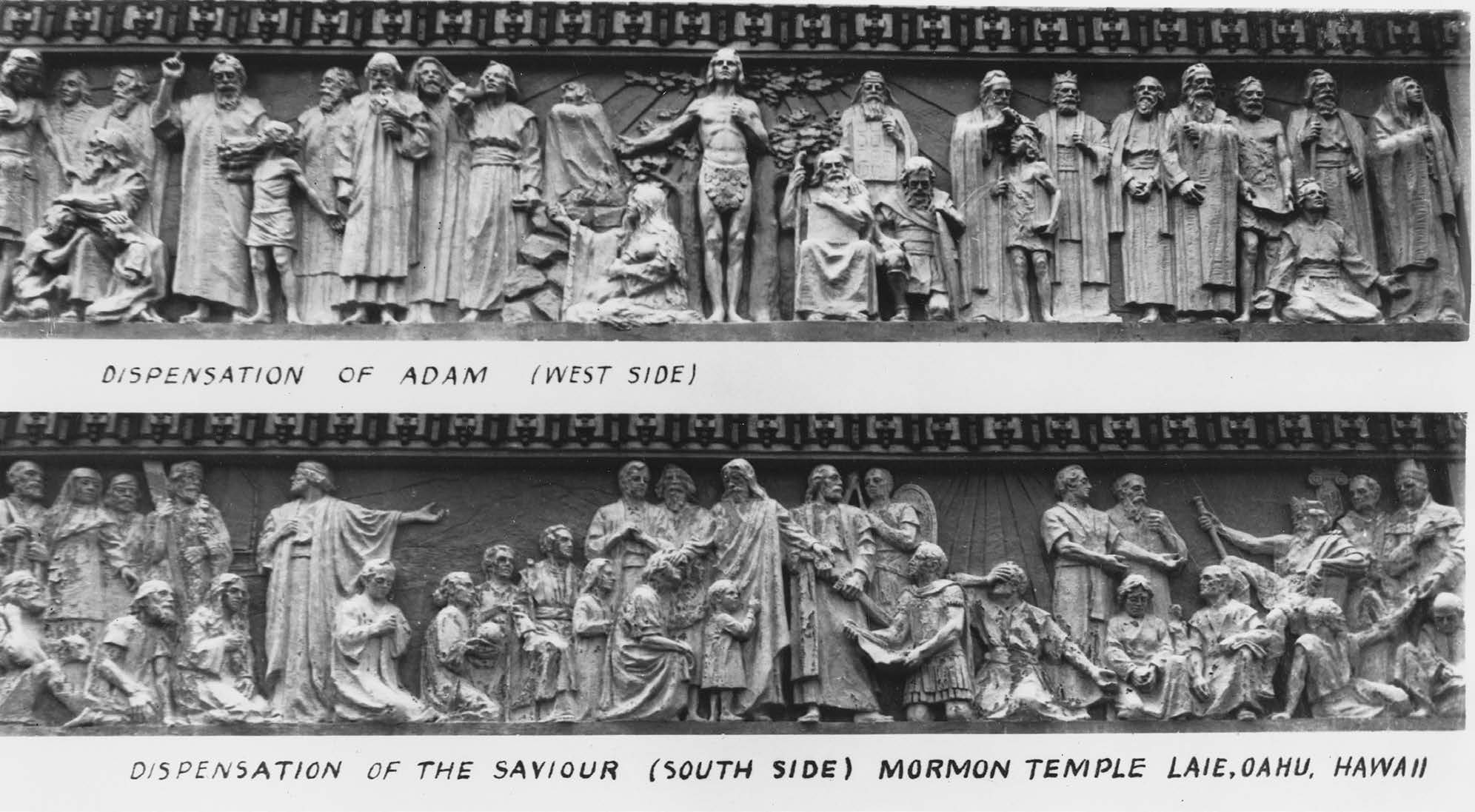

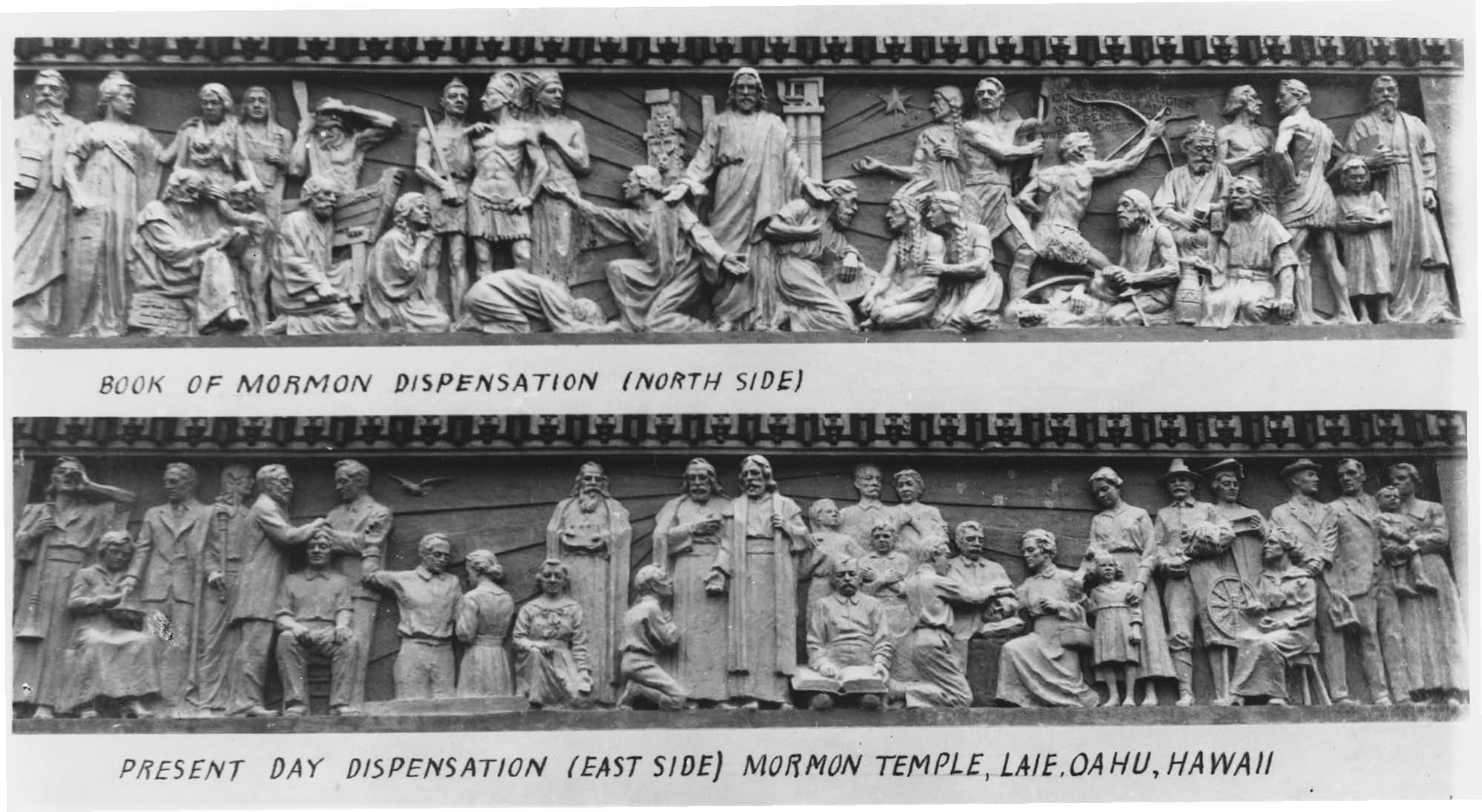

These friezes encircling the temple’s cornice are among a number of artistic adornments to the Laie Hawaii Temple. See additional information on the friezes in appendix 2. Courtesy of Church History Library.

These friezes encircling the temple’s cornice are among a number of artistic adornments to the Laie Hawaii Temple. See additional information on the friezes in appendix 2. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The framed though unfinished temple was striking. There was literally nothing like it in Hawaiʻi, and in its rural setting on a slightly rising hill it stood starkly above a sea of sugarcane fields. However, there was much more to be done, and work proceeded to create an expressive exterior and graceful interior that would imbue the Hawaii Temple with its distinctive character and beauty.

Sculptures: Friezes and Oxen

Recognizing the possibilities of adding symbolism and decor to the temple with the use of cement in plaster molds, architects Pope and Burton added to their design a few isolated sculptured panels to adorn the outside of the temple.[1] With the sculpting of these panels and the oxen for the temple’s baptismal font in mind, the architects approached their friend J. Leo Fairbanks, who had studied art in Chicago and Paris and was then director of art and architecture for the Salt Lake City school district.[2] But it was not Leo alone whom the architects were considering. Leo’s youngest brother, Avard, though still in high school, was recognized as an artistic prodigy; he had already studied at the New York Art Students League (at age thirteen) and had become the youngest artist ever to exhibit work at the prestigious Paris Salon.[3]

Leo was the oldest of ten brothers, Avard the youngest, Leo being nineteen years Avard’s senior. Their father, John Fairbanks, taught art at Brigham Young Academy and was among a group of four artists who studied in Paris under Church sponsorship in 1890 in preparation to paint the murals in the nearly completed Salt Lake Temple. Tragically, six months after Avard was born his mother passed away, and with his father often away trying to provide for the family, Leo in many respects raised Avard with the help of the other teenage children. It was under Leo’s direction that young Avard’s gift for sculpting was recognized.[4]

The original plan called for the sculpting of the oxen and three small panels adorning the upper portion of the temple’s exterior, which were to depict subjects taken from Church history. However, Leo and Avard proposed that the exterior panels be much larger in size and theme.[5] Leo was deeply interested in religious history, and he formulated ideas and worked out sketches for four extensive panels, or friezes, that would encircle virtually the entire temple cornice, each frieze representing one of the four major scriptural eras or dispensations: “The Old Testament,” “The New Testament,” “The Book of Mormon,” and “The Latter Days.” Leo and Avard’s plan was to portray each panel with several characters from its corresponding era in a way that would be inspirational as well as decorative.[6] Leo even consulted his friend, Apostle and scriptural scholar David O. McKay, about the choice and arrangement of these characters. Pope then arranged for Leo and Avard to present their ambitious plans to the First Presidency, who gave their approval.[7]

Work began in August 1916 with the purpose of creating the models in Salt Lake, then ship them to the temple site in Hawaiʻi and have them cast in cement. When devising the friezes, the brothers researched religious books and clothing corresponding to each scriptural era represented. Leo mainly provided content and direction, and Avard sculpted. Each panel was about twenty-four feet long and included about thirty figures, each four feet high (two-thirds life-size). “To give relief, shadows, and strength to the frieze[s], the upper part of the figures are made in full round and the lower part is low relief so that the upper part tips forward” to give the figures better visibility when viewed from below.[8] In all, the friezes include 123 nearly life-size figures.

As work progressed on the friezes, work also began on the twelve oxen. For the baptismal font in the Salt Lake Temple, one ox was cast twelve times, but Avard wanted his oxen to be more lifelike. He carefully studied the animal and determined to craft one section of three oxen in different positions. This section was then reproduced three more times, and when all sections were fitted together, the twelve oxen appeared different when viewed from various angles.[9] Of these oxen Paul Anderson concluded, “For one so young, Avard’s sculpture work is quite astonishing in its expressive quality. The oxen for the baptismal font appear dignified, strong, and lifelike in their movements, perhaps the best ever executed for a temple. Their harmonious integration with the architects’ design for the font gives the whole composition a marvelously unified sense of religious solemnity.”[10]

With the temple structure basically in place by the fall of 1916, the architects were eager for Leo and Avard to complete the models and ship them to Hawaiʻi for casting as soon as possible. With schools dismissing some students early owing to the escalation of World War I, Avard was able to pack and ship the oxen and two of the four friezes and depart for Hawaiʻi in May 1917.[11] The two other friezes (depicting the Book of Mormon and the latter days) would be sculpted in Hawaiʻi.

A set of three distinct oxen were sculpted and then reproduced three more times, giving the effect that all oxen look different when viewed from various angles. © 2010 IRI. Used with

A set of three distinct oxen were sculpted and then reproduced three more times, giving the effect that all oxen look different when viewed from various angles. © 2010 IRI. Used with

permission.

Soon after arriving in Lāʻie, Avard was confronted with a problem: he could not find anyone technically trained to cast his sculptures in plaster. Avard asked Burton to send for Torleif Knaphus, a sculptor from Norway who had been assisting the Fairbanks brothers in Salt Lake City, and John Anderson, an excellent caster who worked in Copenhagen but had moved to Salt Lake City to study.[12] Avard also gained the assistance of three Hawaiians—Charley Lehuakona Broad, his son John, and George Oliwa Alapa—all recently returned from the Iosepa colony in Utah. Avard esteemed these men as “very capable, wonderful character, affable, and quick to learn.”[13]

Avard and his sculpting crew were assigned a shed near the temple in which to work on the friezes, and upon arrival the clay oxen were placed directly in the temple baptistry for casting. In general the sculpting process involved constructing a near-scale frame (often of wood and wire) onto which the clay was attached and molded into the desired shape. After hardening, this sculpted clay was meticulously covered and painstakingly layered with a kind of plaster that Avard described as “glue (a tough gelatin)” that “as it is used is pliable, flexible.” The plaster hardens to a cast that, when separated from the clay sculpture, forms the mold into which the special concrete was poured. Like the temple structure itself, the finished art was “cast stone,” meaning concrete.[14]

Avard Fairbanks (above) was assisted in sculpting by George Oliwa Alapa (below), as well as Charley Lehuakona Broad and his son John; all three had recently returned from the Iosepa colony in Utah. Photos courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Avard Fairbanks (above) was assisted in sculpting by George Oliwa Alapa (below), as well as Charley Lehuakona Broad and his son John; all three had recently returned from the Iosepa colony in Utah. Photos courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Leo came with his wife for two months during the summer to help design the last two friezes, and Avard remained to complete the project. Such sculpting had likely never been seen by those employed at the temple site, and Avard was impressed with how quickly the Hawaiians adjusted themselves to the work. Whenever models were needed, Hawaiian members would pose in costumes sewn by the sisters at the mission home from cloth they could find at the local store. “All this was an experience of a most unusual kind,” recalled Avard of the creative contributions of so many that helped produce the final two friezes, of which all could be proud.[15]

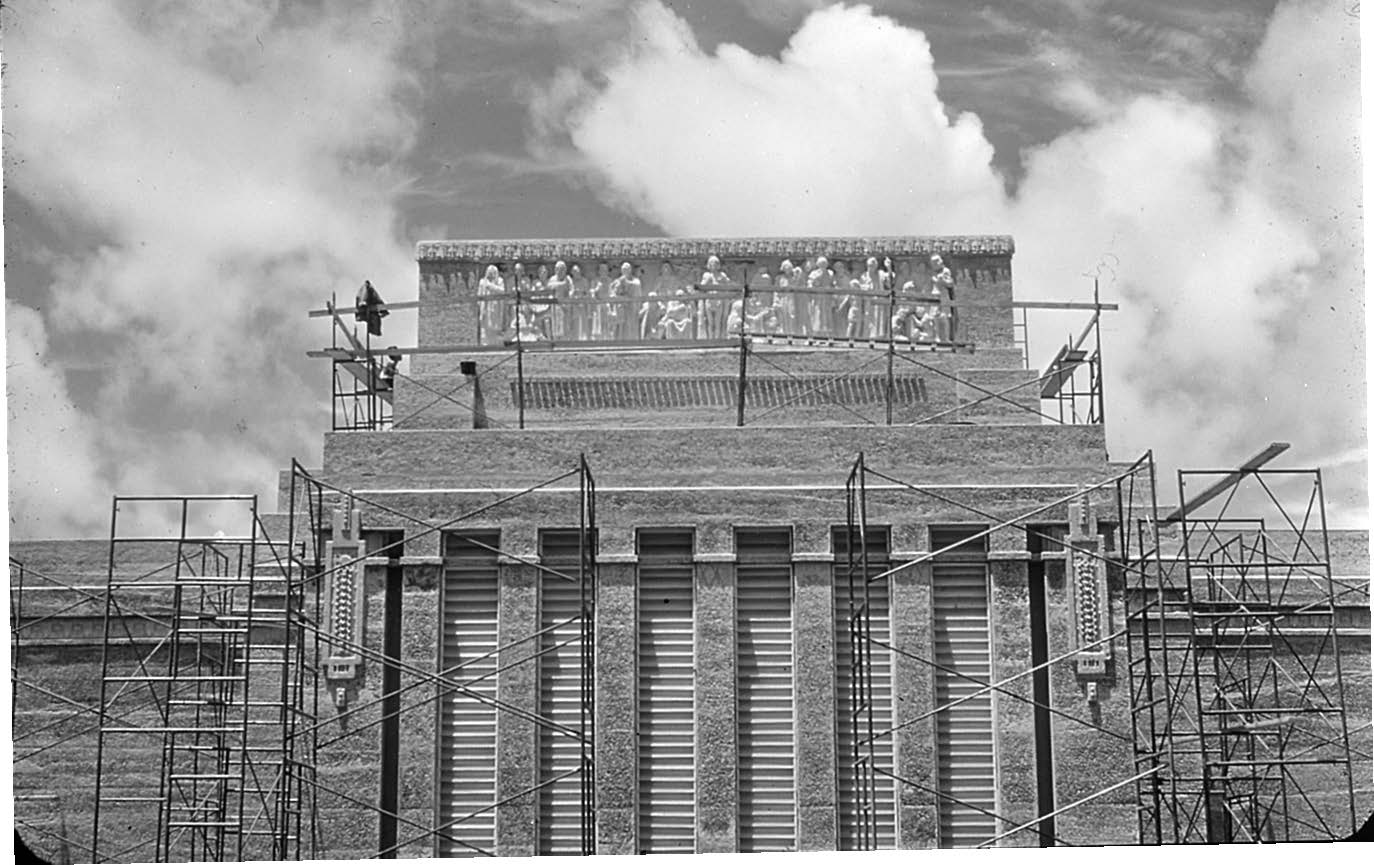

The twenty-four-foot friezes for the top of the temple were simply too large and heavy to cast in single panels, so Avard divided each into sections from five to six feet, choosing partitions that would be least conspicuous. To fit the panels in place, scaffolding was arranged around the temple cornice, and a block-and-tackle system, powered by horses, was set up to lift each section of the friezes into place. Each panel was secured using large iron screws, then retouched before securing the next. This process went on for a couple of months, ending with Avard feeling that “the effects of the completed work were in truth very impressive.”[16] (See appendix A for photos of the friezes and an explanation of their meaning.)

As the frieze panels were curing, the casting of the oxen was done within the temple baptistry, making work on both projects simultaneous. The same process of creating a mold from the clay sculpture and pouring cement therein was used with the oxen; however, the number of molds made was exponentially larger. Not only would the section of three oxen be reproduced three times, but the horns and ears of each oxen (also designed to be distinct) would be cast separately. In all, Avard estimated there were between 160 and 170 cast molds or pieces used to create the font and its oxen. To prevent cracks or seams in the cement from connections made on dry joints, upon completion and placement of all the molds, Avard and his crew remained on the job day and night, pouring the cement for three days. As a result of the strain, Avard became ill and a doctor recommended rest for a couple of weeks. Yet Avard proudly noted later that “the entire job came out beautifully, and I was quite satisfied.”[17]

The friezes were hoisted into place and mounted around the cornice of the temple. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The friezes were hoisted into place and mounted around the cornice of the temple. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Of the handful of haoles (white foreigners) who contributed to the construction of the Hawaii Temple, few so quickly and so deeply took to the Hawaiian people as Avard did. He recorded that soon after arriving in Lāʻie and touring the temple site,

I met the foreman of construction, Hamana Kalili, a native Hawaiian of very robust proportions. We promptly became very good friends, and Hamana soon regarded me, a young sculptor, like a son. He related many of the Hawaiian legends, and invited me to social events, which I enjoyed, appreciating the opportunity of learning about an ancient culture with their interesting traditions. I learned the songs and often sang with the workers. The Hawaiians love to sing, have beautiful voices, and a marvelous sense of rhythm. They sing at work; they sing when pounding poi; they sing when paddling their outrigger canoes; [etc.].[18]

Art historian Paul Anderson wrote, “The oxen for the baptismal font appear dignified, strong, and lifelike in their movements, perhaps the best ever executed for a temple.” Courtesy of

Art historian Paul Anderson wrote, “The oxen for the baptismal font appear dignified, strong, and lifelike in their movements, perhaps the best ever executed for a temple.” Courtesy of

Church History Library.

When waiting for the cement to cure, Hamana taught Avard to ride a surfboard and took him fishing in his outrigger canoe. “It was a wonderful experience . . . to be in that beautiful setting,” recalled Avard, “near to the temple, and in among the Hawaiian people . . . in the little town of Laie. . . . There was a spiritual atmosphere which was felt in the entire community.”[19]

Perhaps the purpose and potential impact of the sculpted art of the Hawaii Temple are best expressed in J. Leo Fairbanks’s creed: “Art is for service; for making things beautiful as well as useful; for lifting men above the sordid things that grind and depress: to give a joyous optimism in one’s work; . . . to take pleasure in seeing beauty as it exists in what man has made as well as in one’s immediate environment. . . . To me, the purpose of art is to visualize ideals, to realize ideals, and to idealize realities.”[20]

Murals

Hamana Kalili, sculpted by Avard Fairbanks. Hamana, a foreman on the temple site, took young Avard under his wing, and the two formed a lasting friendship. Photo courtesy of Gary Davis.

Hamana Kalili, sculpted by Avard Fairbanks. Hamana, a foreman on the temple site, took young Avard under his wing, and the two formed a lasting friendship. Photo courtesy of Gary Davis.

Work on the temple’s interior began in December 1916 and took approximately sixteen months to complete, though some fine-tuning continued.[21] Of the many beautiful features of the temple’s interior, some of the most recognizable are its stunning murals.

The commission to paint murals in the creation, garden, and world rooms was originally given to German immigrant Fritzof E. Weberg, who was to be assisted by Utah painter Lewis A. Ramsey. However, when Weberg was unable to fulfill the task, Ramsey, who had studied in Paris along with J. Leo Fairbanks and had established himself as a skilled landscape and portrait painter, was authorized to complete the commission.[22]

Ramsey developed sketches for the murals in January and February 1917 and completed all three rooms before returning home in the early summer. In the murals for the creation and garden rooms, the ocean and tropical foliage suggested local Hawaiian scenery. For the lone and dreary world, however, the scene shifted to the Rocky Mountains, complete with deer and bears. Sadly, however, these murals did not survive. Ramsey had recommended against mounting the canvas for the murals directly on the walls, fearing moisture problems, but was overruled. His concerns proved to be justified, and not long after his departure the newly completed murals began to deteriorate from moisture and mold.[23]

LeConte Stewart

Providentially, a twenty-four-year-old missionary named LeConte Stewart had recently arrived in the Hawaii Mission. He was an accomplished painter, having received advanced training at the New York Art Students League.[24] Upon his arrival, Elder Stewart was taken to the mission home in Lāʻie and was awestruck by the beauty of the temple. Contrasted with the island’s natural terrain, expansive fields of sugarcane, and hillsides covered in rows of pineapple, the temple to him stood out “like a great star” and was unlike anything he had ever seen.[25]

Painted by LeConte Stewart, each framed mural in the creation room depicts a stage of the Creation. © 2010 IRI. Used with permission.

Painted by LeConte Stewart, each framed mural in the creation room depicts a stage of the Creation. © 2010 IRI. Used with permission.

Before his mission, Stewart had met architect Harold Burton in Salt Lake City. Now, drawn together by mutual interests, these talented young men talked for hours about their artistic philosophy, the temple, and its interior decor and furnishings. Burton recommended that Stewart be placed in charge of the interior painting of the temple and other decorative work, and three weeks after his arrival, Stewart was reassigned to work on the temple in Lāʻie.[26]

When it became evident that Ramsey’s murals would need to be replaced, the architects collaborated with Stewart to produce miniature sketches for new creation room murals. Rather than filling the whole wall, the proposed murals would be a series of long narrow panels framed in the horizontal moldings around the room. The new sketches and new approach were submitted to the First Presidency and approval arrived weeks later.[27]

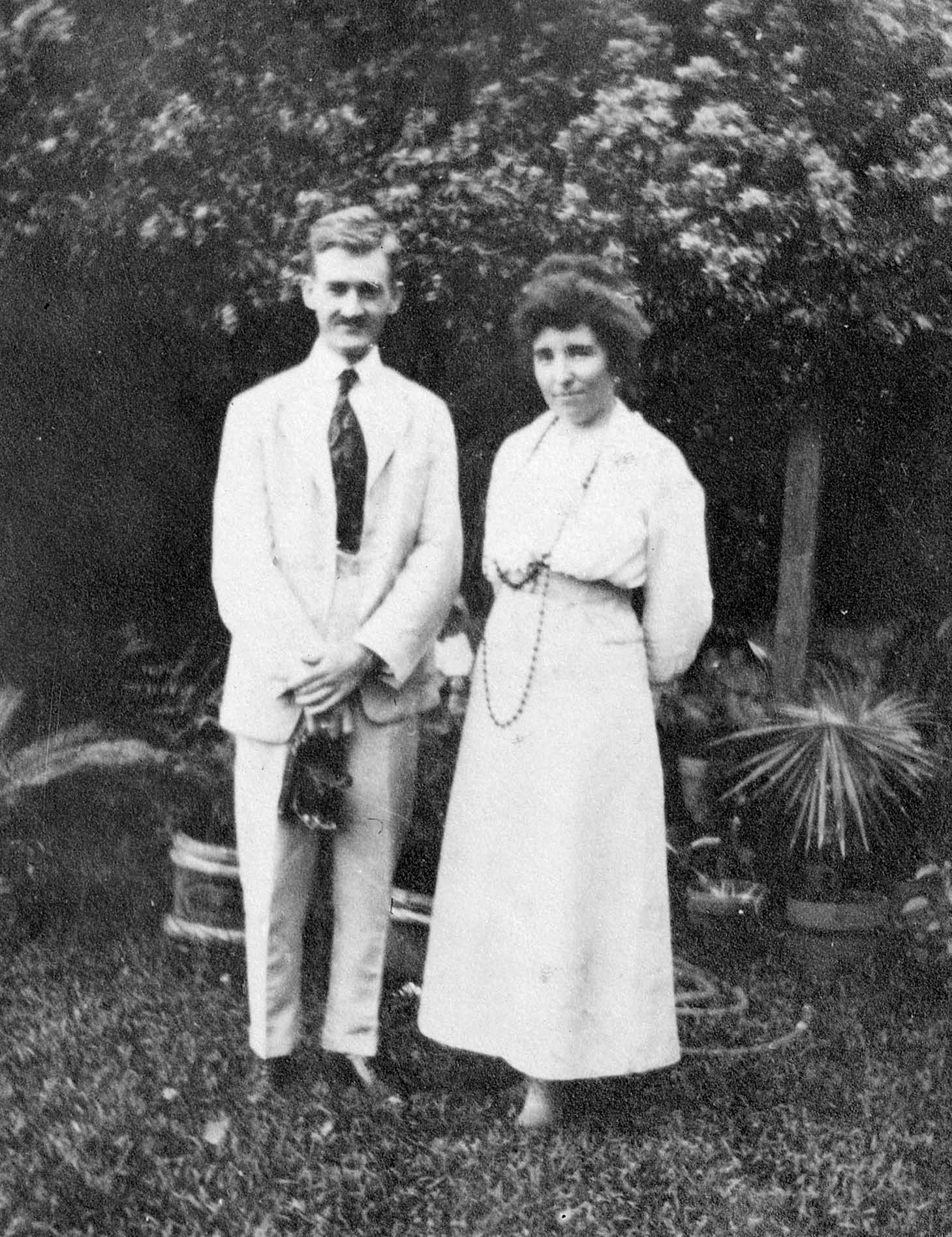

LeConte and Zipporah Stewart. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

LeConte and Zipporah Stewart. Courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

Stewart spent hours prayerfully studying the book of Genesis and other Creation scripture in an effort to authentically tell the Creation story “in a different delightful artistic way.”[28] He worked long hours, and sometimes late into the night, to complete the work. His supervisors were pleased when the creation room was complete, and Stewart was further assigned to paint the garden room in a series of panels portraying “groves of beautiful trees, lawns and flowering shrubs, among which are various animals, all evidently living together in peaceful association.”[29] Yet painting was not LeConte Stewart’s only contribution to the temple—he also helped supervise the general decorative work throughout the temple, including assisting in choosing furniture, carpets, and drapes that harmonized with and complemented the painted walls and murals.[30]

As LeConte Stewart began his work on the temple, his fiancée, Zipporah Layton, joined him in Hawaiʻi and they were married. As LeConte painted, Zipporah taught at the Church school in Lāʻie. She later recorded, “After school and on Saturdays, I spent hours in the temple doing odd jobs and trying to give Stewart support in his new work. Seems like together we prayed about it and thought about it night and day for we were young, and we felt the great responsibility of doing work in a temple of God. Surely God did hear and answer our prayers.”[31]

Alma B. Wright

The assignment to repaint the world room fell to yet another talented Latter-day Saint artist. Alma B. Wright, a college art instructor in Logan, Utah, had studied in Paris at the same time as Lewis Ramsey and Leo Fairbanks. Wright had become well known for his portraits, and Church leaders in Utah had arranged for Wright to go to Hawaiʻi and paint a series of murals in the temple baptistry. Then, as the need arose, he was asked to paint the world room as well. Quite different from Stewart, his murals of the lone and dreary world were done in a hard-lined style. The murals depict wild beasts in combat, broken and rocky mountains, storm-swept landscapes, and gnarled trees.[32] Some of the background areas have a softer, more impressionistic feeling, suggesting Stewart’s assistance or retouching of those places.[33]

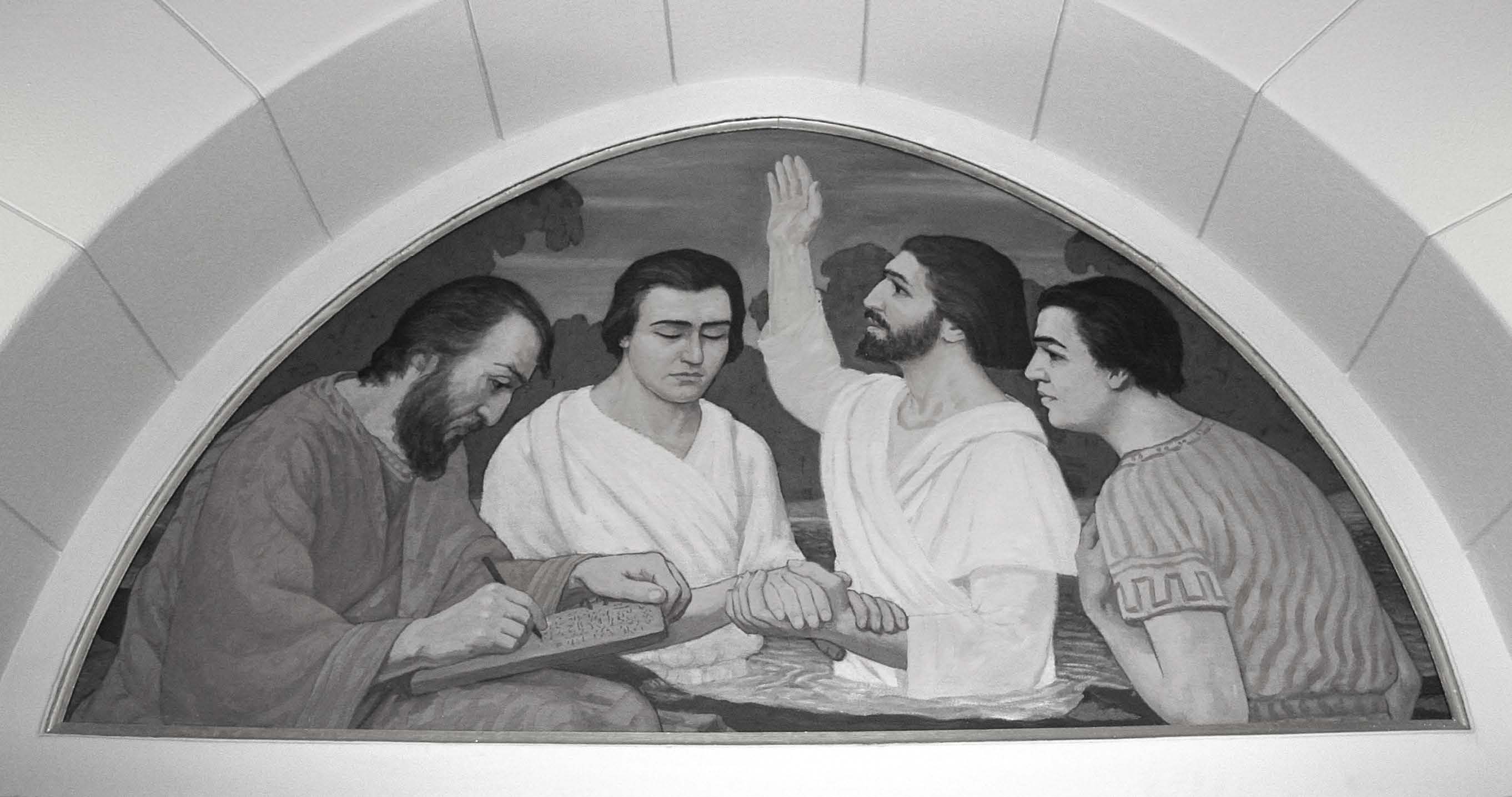

In the arches of the baptistry there are also seven colorful murals, or lunettes, painted by Wright, “illustrating in an original manner the first principles and ordinances of the gospel by means of historical incidents selected from the Bible and the Book of Mormon.”[34] These paintings include Receiving Priesthood Blessing,[35] Administering to the Sick, Jesus Baptized by John the Baptist, Preaching the Gospel, Alma Rebuking Corianton, Baptism, and Healing the Blind.[36]

A heightened experience

The use of film in portraying the endowment ceremony would not be incorporated into the Hawaii Temple experience until 1978. Thus for nearly sixty years patrons relied exclusively on these murals by Stewart and Wright for a visual representation of the creation, the garden, and the world. Now joined by a film, these murals continue to heighten and enhance the kinetic learning experience that is a hallmark of temples everywhere.

Interior Work

Though very visible, murals accounted for only a fraction of the work that needed to be done within the temple, so much of which goes unnoticed. Electrical work and plumbing were integral considerations from start to finish. All interior walls needed to be weatherized, sheeted, plastered, and painted with multiple coats. Custom woodwork including trim, baseboards, paneling, and more needed to be installed and detailed. Custom glass art and marble and tile arrangements were also added. Windows were fitted, set, and weatherized; doors were hung while custom furniture, carpets, and draperies were ordered, then assembled and installed. Hardware such as faucets, door handles, and light fixtures were installed, and the list goes on.

The colorfully painted lunettes in the baptistry were created by Alma B. Wright and portray the

The colorfully painted lunettes in the baptistry were created by Alma B. Wright and portray the

ministry of the Aaronic Priesthood. © 2010 IRI. Used with permission.

What’s more, President Rudger Clawson, Acting President of the Quorum of the Twelve, noted, “The interior workmanship and finish are first class in all respects.”[37] The materials used were some of the finest. Hardwoods were used, including “Hawaiian Koa, a native wood of the island which rivals the choicest mahogany in the beauty of grain and color.” The baptistry and other rooms included mosaic tile and marble (the latter shipped from Vermont through the recently completed Panama Canal).[38] Furthermore, the work was meticulous. LeConte Stewart spent days lying on a board hung from the temple roof putting 18-karat gold leaf detail on the fretwork with a camel-hair brush.[39] Of the original interior, Paul Anderson explains:

The completed ordinance rooms were carpeted with heavy velvet pile rugs. The windows were draped with Japanese silk. Unpolished oak moldings ornamented most of the major rooms. One of the sealing rooms was paneled in precious Hawaiian Koa wood. The high windows in the celestial room were leaded in a geometric pattern [representing the Tree of Life]. . . . The furniture for the temple was made by Fetzer Furniture in Salt Lake City to the architects’ specifications. In keeping with the temple’s architecture, the chairs and tables were straight and geometric. . . . The furniture was made of oak to match the architectural woodwork, with some contrasting wood inlays on more prominent pieces.[40]

Close-up of lunette in baptistry. © 2010 IRI. Used with permission.

Close-up of lunette in baptistry. © 2010 IRI. Used with permission.

Finally, architects Pope and Burton, along with LeConte Stewart, arranged the finished interior to symbolically convey progression. Like the ascending layout of the rooms themselves, the decor in the ordinance rooms leading to the celestial room incorporated increasingly elegant woods and detail to strengthen the symbolism of advancement toward celestial exaltation.[41] Describing the pinnacle room in this process, in 1919 President Clawson said:

The walls and ceiling of the Celestial room are paneled, [and] bordered with genuine oak, and striped with gold leaf, producing a most harmonious and delightful effect. A Wilton carpet covers the floor, and gold colored silk plush portieres hang in the recesses of the room on all sides. A soft, mellow light is furnished by windows high up just under the ceiling, and a handsome chandelier sheds forth a subdued electric light when darkness comes on. This, of course, is the largest and most beautiful of all the Temple rooms, and one’s entrance there seems to bring him into an atmosphere of absolute peace. It is indeed a heavenly place.[42]

Notes

[1] See J. Leo Fairbanks, “The Sculpture of the Hawaiian Temple,” Juvenile Instructor, November 1921, 575; and Hyrum C. Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” Improvement Era, December 1919.

[2] See Robert S. Olpin, William C. Seifrit, and Vern G. Swanson, Artists of Utah (Salt Lake City: Gibbs Smith, 1999).

[3] See Eugene F. Fairbanks, A Sculptor’s Testimony in Bronze and Stone: The Sacred Sculpture of Avard T. Fairbanks, rev. ed. (Salt Lake City: Publishers Press, 1994); and Paul L. Anderson, “A Jewel in the Gardens of Paradise: The Art and Architecture of the Hawaiʻi Temple,” BYU Studies 39, no. 4 (2000): 170–73.

[4] See Fairbanks, Sculptor’s Testimony, 1; and Athelia T. Woolley, “Art to Edify: The Work of Avard T. Fairbanks,” Ensign, September 1987.

[5] See Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 170–73.

[6] See Fairbanks, “Sculpture of the Hawaiian Temple”; and Avard Fairbanks, transcript 1, in authors’ possession.

[7] See Avard Fairbanks, transcript 1.

[8] Fairbanks, “Sculpture of the Hawaiian Temple,” 575.

[9] See Avard Fairbanks, transcript 1.

[10] Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 172.

[11] See Avard Fairbanks, transcript 1.

[12] See Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3, in authors’ possession. For biographical information about these artists, see Robert S. Olpin, Dictionary of Utah Art (Salt Lake City: Salt Lake Art Center, 1980).

[13] Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3.

[14] Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3.

[15] Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3.

[16] Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3.

[17] Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3.

[18] Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3.

[19] Avard Fairbanks, transcript 3.

[20] Fairbanks, Sculptor’s Testimony, 11.

[21] The final progress report, filed in March 1918, stated, “Odds and ends of various kinds in the interior have been finished.” Correspondence and Reports Relating to the Building of the Laie, Hawaii Temple, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, BYU–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI (hereafter cited as BYU–Hawaii Archives).

[22] See Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 177.

[23] See Lewis A. Ramsey, correspondence 1916–17, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL). In “The Hawaiian Temple,” Millennial Star, 8 January 1920, 31, Rudger J. Clawson noted: “A serious obstacle was encountered when the heavy rains came and caused a kind of fungus or mildew to appear on the canvas-covered walls of the interior. By reason of the humidity of the atmosphere, which caused the walls to sweat, this was hard to control. After practically completing three rooms, it became necessary to take off the canvas. The walls were then treated with a damp-proof preparation, also a special paste was used to stick the canvas to the walls, which proved very satisfactory and eliminated further trouble in this direction.” See also Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 177–78. In addition to the murals that were lost, Lewis Ramsey produced two portraits—one of George Q. Cannon, the other of Joseph F. Smith—that continue to be displayed in the temple today.

[24] See Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 178.

[25] Zipporah Layton Stewart, reminiscence of Hawaiian Temple, 1894–1984, CHL.

[26] See Zipporah Layton Stewart, reminiscence; Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 178; and Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, BYU–Hawaii Archives, 1 July 1917.

[27] See Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 178; and Zipporah Layton Stewart, reminiscence.

[28] Zipporah Layton Stewart, reminiscence.

[29] Duncan M. McAllister, A Description of the Hawaiian Temple of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Erected at Laie, Oahu, Territory of Hawaii (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 1921), 14.

[30] See Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii”; and Zipporah Layton Stewart, reminiscence.

[31] Zipporah Layton Stewart, reminiscence.

[32] See McAllister, Description of the Hawaiian Temple, 14.

[33] See Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 179.

[34] Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” 153.

[35] This particular lunette, originally part of the baptistry, is now visible only within the stairwell leading to the creation room.

[36] See Ann Marie Atkinson files, “Laie Temple Interior,” in authors’ possession.

[37] Clawson, “Hawaiian Temple,” 31.

[38] Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii,” 151. Further details on materials used can be found in Correspondence and Reports Relating to the Building of the Laie, Hawaii Temple, BYU–Hawaii Archives.

[39] Zipporah Layton Stewart, reminiscence.

[40] Anderson, “Jewel in the Gardens,” 179. See McAllister, Description of the Hawaiian Temple.

[41] See Pope, “About the Temple in Hawaii”; and Richard O. Cowan, “Latter-day Saint Temples as Symbols,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 21, no. 1 (2012): 2–11, http://

[42] Clawson, “Hawaiian Temple,” 31.