Prologue

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "Prologue," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), xix–xxii.

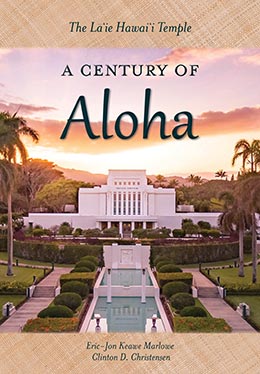

“Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi (1832–1919). This sculpture graces the entrance to the Laie Pioneer Memorial Cemetery, adjacent to the Laie Hawaii Temple. Sculpted by Jan Fischer. Courtesy of Gary Davis.

“Ma” Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi (1832–1919). This sculpture graces the entrance to the Laie Pioneer Memorial Cemetery, adjacent to the Laie Hawaii Temple. Sculpted by Jan Fischer. Courtesy of Gary Davis.

Sometime in the early 1850s, on the Hawaiian island of Maui,[1] Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi and her husband favorably received haole[2] missionaries and their message of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. Later this young couple cared for a severely ill teenage missionary. This youthful missionary had lost his father and his uncle (after whom he was named) at age five and then his mother a few years before he embarked on his mission at age fifteen. The motherly care shown the orphan missionary was never forgotten, and the young elder’s experience among the Hawaiian people played a pivotal role in his becoming a man. He later described the early years of his youth as “a comet or a fiery meteor, without . . . balance or guide” and credited his mission to Hawaiʻi for having “restored my equilibrium, and fixed the laws . . . which have governed my subsequent life.”[3]

Little more is known of this caring Hawaiian couple, but like many other early Hawaiian converts to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the islands, they would have endured breaches of apostasy within the Church and general persecution from without. What’s more, as Native Hawaiians they would have endured epidemics of disease leading to the death of much of their race, tumultuous governance, and unimaginable change as their once-isolated society became increasingly exposed to the outside world.

The fate of the husband is unknown, but Sister Manuhiʻi remained connected to her faith. And remarkably, more than sixty years later, this devoted sister and the young missionary she cared for were reunited on a pier in Honolulu in 1909. She called out for “Iosepa,” Joseph, and he instantly ran to her, hugging her and saying, “Mama, Mama, my dear old Mama.” The boy she had cared for was now the prophet of the Church, Joseph F. Smith; and the caring sister, now blind and frail, had brought him the best gift she could afford—a few choice bananas.[4]

“Ma” Manuhiʻi’s enduring faith and her heartfelt but meager gift of bananas are telling. While her faith was deep and abiding, her meager means meant that the fulness of the gospel, realized only in temples thousands of miles away, was not a reality for her. This inaccessibility to temples, faced by Ma Manuhiʻi and so many other Saints in distant lands, had been a conundrum for Church leaders for years, and possibly the most outspoken of those leaders on that subject was Ma’s “son” Joseph F. Smith.[5]

Years later, Ma learned that her beloved Iosepa would again visit the islands, and she waited for days on the steps of the mission house in Honolulu, anticipating his arrival. The prophet and his party had an exceptional visit, and it appears that before his departure he promised Ma that she would live to attend the temple.[6] Three months later, in the October 1915 general conference, President Joseph F. Smith proposed the construction of a temple in Hawaiʻi. It was unanimously approved.

Although construction advanced promptly, President Joseph F. Smith did not live to see the Hawaii Temple completed among a people he loved so dearly, but Ma did. In her nineties and among the first to attend, Ma was carried through the temple to receive her blessings and be sealed to her husband. While in the temple, she heard the voice of Joseph F. Smith tell her “Aloha,” and a dove flew in through an open window and alighted on her bench. Expressing her feeling of deep contentment, Ma passed away a week later.[7] Ma is buried near the temple, and a statue of her now resides next to the temple in honor of her, and so many others like her, whose faith laid the foundation for a temple in Hawaiʻi.[8]

Notes

[1] Nathaniel R. Ricks, My Candid Opinion: The Sandwich Islands Diaries of Joseph F. Smith, 1856–1857 (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2011), 157n2. However, it is also suggested this event took place on the island of Molokaʻi in Joseph Fielding Smith, The Life of Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1972), 185.

[2] Haole is a Hawaiian term for a person who is a nonnative Hawaiian, especially a white person.

[3] Joseph F. Smith to Samuel L. Adams, 11 May 1888, Truth and Courage: Joseph F. Smith Letters, ed. Joseph Fielding McConkie (Provo, UT: printed by the editor, 1988), 2.

[4] Charles W. Nibley, “Reminiscences of President Joseph F. Smith,” Improvement Era, January 1919, 191.

[5] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1901, 69; and October 1902, 3.

[6] Elder Isaac Homer Smith, then serving in Honolulu, recorded his recollection: “He [the prophet] promised her [Ma Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi] on this occasion that she would live to receive her blessings in the House of the Lord.” Brief History of the Life of Isaac Homer Smith, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI.

[7] William M. Waddoups, journal, 5 December 1919, William Mark and Olivia Waddoups Papers, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT. See Wilford W. King, “Hawaiian Mission,” Liahona the Elders’ Journal, 3 February 1920, 271; and “‘God Hates a Quitter’: Elder Ford Clark: Diary of Labors in the Hawaiian Mission, 1917–1920 & 1925–1929,” Mormon Pacific Historical Society 28, no. 1, article 9 (2007).

[8] The two most common sources for the story of Ma Nāʻoheakamalu Manuhiʻi are Joseph Fielding Smith, comp., Life of Joseph F. Smith: Sixth President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1938), 185–86; and Nibley, “Reminiscences,” 193–94.