A New Era in Temple Building

Eric-Jon Keawe Marlowe and Clinton D. Christensen, "A New Era in Temple Building," in The Lā'ie Hawai'i Temple: A Century of Aloha (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 31–42.

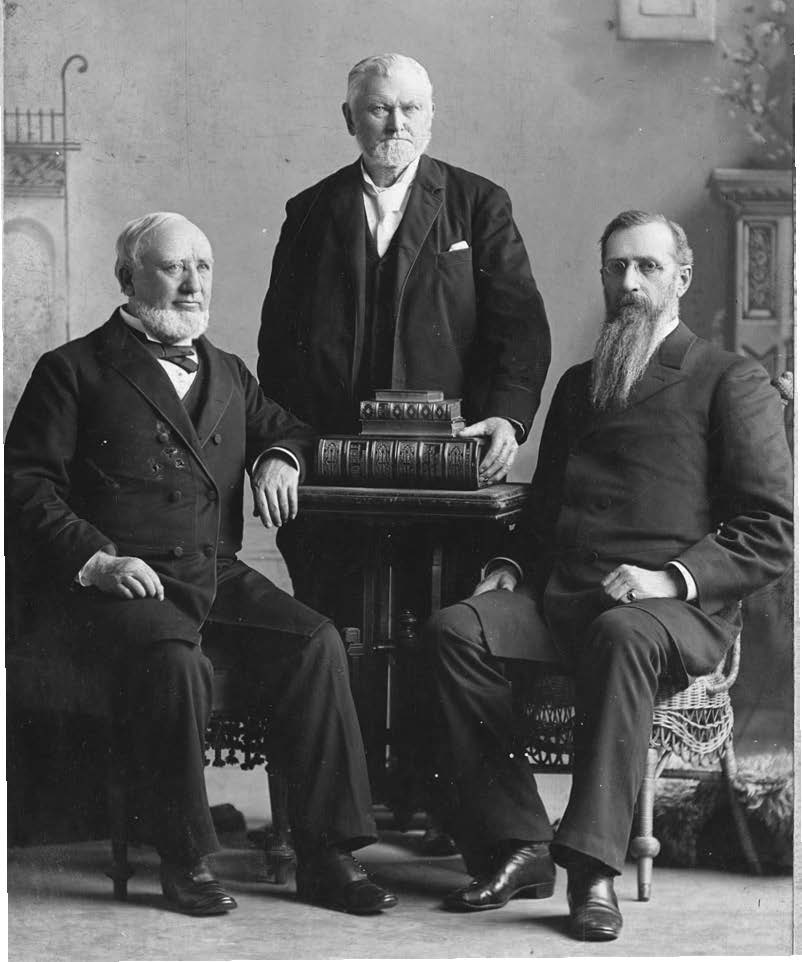

George Q. Cannon (front row center) of the First Presidency visited Hawai‘i in 1900 to celebrate the mission’s golden jubilee. Impressed by the Hawaiian Saints’ faith, he spoke openly to them of temple blessings that would come to the islands. To his left are Alice and Samuel E. Woolley, to whom he confided his certainty that a temple would one day be built in Hawai‘i. Young missionary William M. Waddoups (behind Sister Cannon) would be called eighteen years later by Joseph F. Smith to serve as the temple’s first president. Courtesy of Church History Library.

George Q. Cannon (front row center) of the First Presidency visited Hawai‘i in 1900 to celebrate the mission’s golden jubilee. Impressed by the Hawaiian Saints’ faith, he spoke openly to them of temple blessings that would come to the islands. To his left are Alice and Samuel E. Woolley, to whom he confided his certainty that a temple would one day be built in Hawai‘i. Young missionary William M. Waddoups (behind Sister Cannon) would be called eighteen years later by Joseph F. Smith to serve as the temple’s first president. Courtesy of Church History Library.

The twenty-six years between the founding of Iosepa in 1889 and the announcement of a temple in Hawaiʻi in 1915 was a time of significant change in the Church as a whole, and in Hawaiʻi as well. To be sure, the doctrine that temples would be built throughout the world had already been well established. Brigham Young stated, “To accomplish this work there will have to be not only one temple but thousands of them.”[1] It had never been a matter of if, but rather when and where conditions would be suitable for more temples to be built. However, after the Logan Utah Temple was announced in 1876, more than thirty-five years would pass before the next wave of temples, including the one in Lāʻie, Hawaiʻi, would be announced.[2]

A Hiatus in Temple Building

Effect of US government crackdown on polygamy

This gap in the announcement of more temples began with the presidency of John Taylor (1877–87), a time when the Church was being persecuted for the practice of plural marriage. Beyond outlawing polygamy, which resulted in the arrest of hundreds of Church members, the US government sought to dismantle the Church as a political and economic organization.[3] The seizure of Church property, confiscation of holdings, and removal of voting rights ensued. As a result, when Wilford Woodruff assumed the presidency in 1889, Church debt was mounting, arrests continued, member immigration was curtailed, and territorial political power was increasingly in the hands of politicians who were hostile to the Church. Finally, Church leaders learned that the Utah US attorney was investigating the management of Church property, and in late August 1890 President Woodruff received confirmation that the US government was going to confiscate the temples.[4]

Shortly thereafter, during general conference on 6 October, President Woodruff issued what is known as “the Manifesto,” declaring that the Church would no longer teach plural marriage nor permit members to enter into it. Later, he explained that the Lord had shown him by revelation what would take place if plural marriage did not cease—namely, the “confiscation and loss of all the temples, and the stopping of all the ordinances therein, both for the living and the dead.” However, discontinuing the practice of plural marriage would “leave the Temples in the hands of the Saints, so that they can attend to the ordinances of the Gospel, both for the living and the dead.”[5]

The burden of Church debt

Under threat of temples being confiscated, President Wilford Woodruff received a revelation known as “the Manifesto,” which led to the end of plural marriage and the continuation of temple

Under threat of temples being confiscated, President Wilford Woodruff received a revelation known as “the Manifesto,” which led to the end of plural marriage and the continuation of temple

work. Photo by Charles Roscoe Savage courtesy of Church History Library.

Although the desire to build more temples was constant, the Church simply did not have the resources to do so. The challenges associated with plural marriage, combined with economic conditions of that era, left the Church in considerable debt.[6] This burden extended throughout the 1890s and weighed heavily on the presidency of Lorenzo Snow.[7] While speaking at the St. George Tabernacle on 17 May 1899, President Snow told the Saints that they had neglected the law of tithing and that the Church would be relieved of its debts, and they of their drought, if members would pay a full tithing. Through emphasis on the law of tithing throughout the Church, President Snow placed the Church on a path to financial solvency that would eventually allow the construction of more temples.[8]

Shift in Gathering

From the time the Church was organized, members had been encouraged to gather to the center of the Church—Zion (see Doctrine and Covenants 29:7–8). Whether this gathering took place in Kirtland, Nauvoo, or the Rocky Mountains, the resulting unity helped the Saints to forge spiritual strength in a refuge free from persecution and sin. Furthermore, the policy of gathering members to Zion produced the resources needed to build temples.[9] However, by the turn of the century the Church was no longer encouraging immigration. As things were, Latter-day Saint settlements in Utah found it increasingly difficult to support large numbers of immigrants. Moreover, the resulting depletion of member strength in foreign lands hindered missionary work.[10] Thus the Saints were asked to “stay and build up the work abroad.”[11] Almost concurrent with the new emphasis on having the Saints gather in branches, wards, and stakes throughout the world, Church leaders began considering how to provide all members, not just those living near the center of the Church, with the ordinances of the temple.

Overthrow of the Hawaiian Kingdom

Just as the Church was experiencing significant change at the end of the nineteenth century, conditions in Hawaiʻi were shifting as well. During its rule the Hawaiian Kingdom endured repeated British, French, and US attempts to exert influence over it. Over time, American business ventures and Protestant missionizing, both facilitated by Hawaiʻi’s proximity to US ports, increasingly linked the Hawaiian and US economies. Trade treaties strengthened those ties, and eventually US sugar plantation owners came to dominate Hawaiʻi’s economy and politics. When Queen Liliʻuokalani sought to reestablish a stronger monarchy, a group of American businessmen deposed her in 1893, removing the Hawaiian monarchy from power. The Church did not take a political stand in this matter; however, Church members in Hawaiʻi (nearly all native) were displeased. Hawaiʻi was annexed by the United States in 1898 and became a territory in 1900 (later becoming a state in 1959).

Making the Lāʻie Plantation Profitable

Though the Church’s financial ventures had generally been communal and cooperative, as its debt mounted in the 1890s and industry expanded throughout the US, the Church increasingly turned to more capitalist business practices.

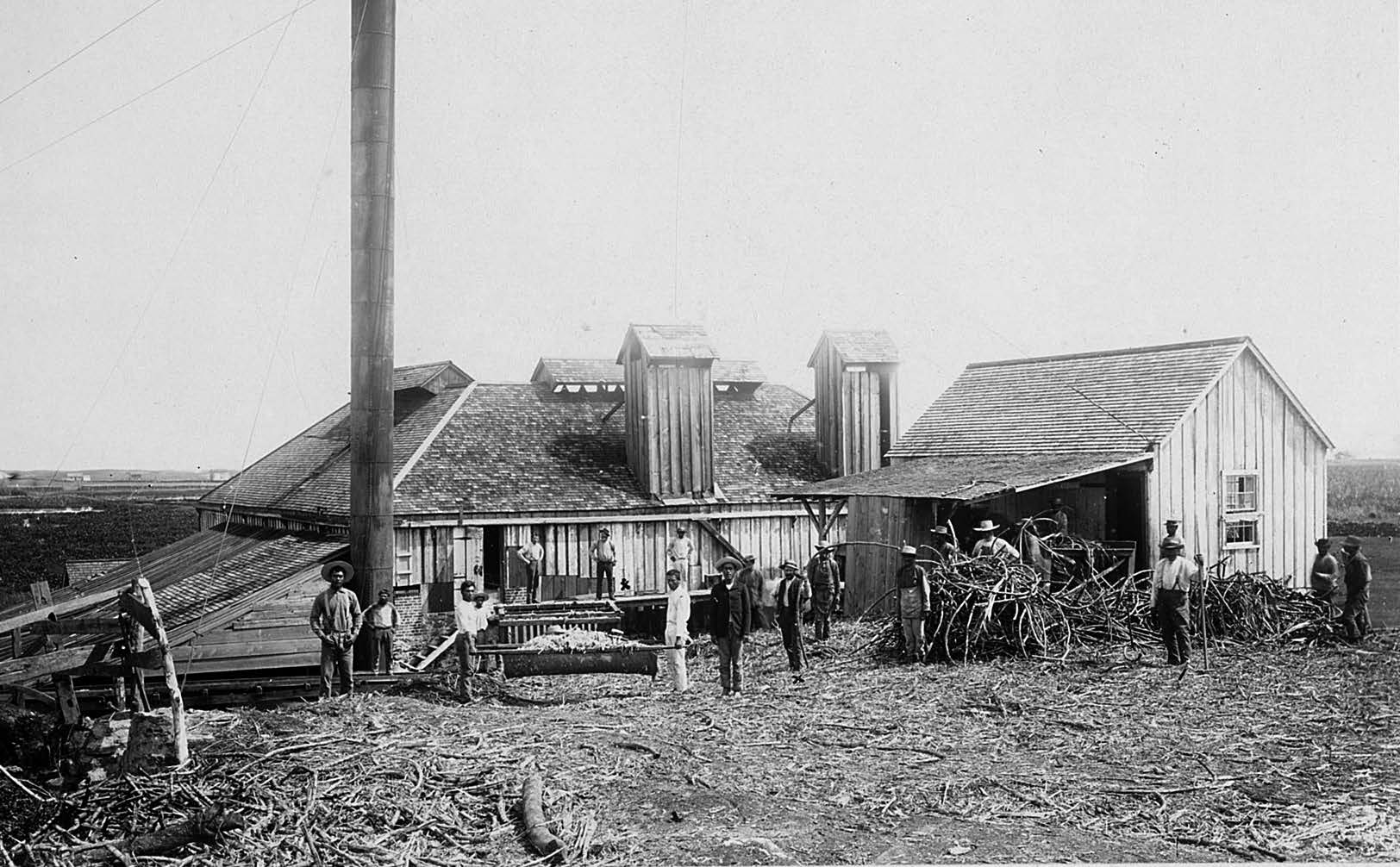

This shift can be seen in the administration of the Lāʻie Plantation, where, among other crops, sugarcane was increasingly grown and harvested industrially. For one, the Church could ill afford to prop up the plantation in hard times as it had in the past, and if the plantation could be enlarged and made to be more profitable, labor opportunities would increase, allowing more Hawaiian Saints to gather to Lāʻie.[12] The move toward increasing the plantation’s profitability began during the mission presidency of Matthew Noall (1891–95) and was expanded during the mission presidency and plantation management of Samuel E. Woolley (1895–1921). It was the economic success of the Lāʻie Plantation, combined with Hawaiian member donations, that would allow the temple to be constructed without financial assistance from Church headquarters.

Visit of George Q. Cannon

In the 1890s sugarcane was increasingly grown and harvested industrially on the Church plantation at Lāʻie. The Lāʻie Plantation’s economic success, combined with Hawaiian member donations, would allow the temple to be constructed without financial

In the 1890s sugarcane was increasingly grown and harvested industrially on the Church plantation at Lāʻie. The Lāʻie Plantation’s economic success, combined with Hawaiian member donations, would allow the temple to be constructed without financial

assistance from Church headquarters. Photo of sugar mill courtesy of Church History Library. Photo of sugarcane harvest courtesy of BYU–Hawaii Archives.

The year 1900 was the fiftieth anniversary of the Hawaii Mission. In celebration President George Q. Cannon, one of the original ten missionaries in Hawaiʻi and now First Counselor in the First Presidency, traveled to Hawaiʻi to attend the festivities. It was during this gratifying visit that President Cannon, on at least two occasions, openly spoke to the Hawaiian Saints about the possibility of receiving temple blessings.

Of President Cannon’s comments during Sunday meetings in Lāʻie on 23 December, Elder Fred Beesley recorded: “He exhorted the Saints very strongly to live pure and virtuous lives and if they were faithful and would strive to be worthy they would have the privilege to be sealed in marriage. He remarked that the sealing power would be given to the president of the mission, so that the ordinance of sealing would be accorded . . . without their going to the temples in Zion.”[13] Mission president Samuel E. Woolley reprised that instruction in these words: “If they would only be faithful enough, the time would come when someone would be given the power to seal husband and wife for time and eternity so that their children would be born under the new and everlasting covenant.”[14]

President Cannon’s journal preserves the essence of what he said in Honolulu a week later:

[In Sunday School] I spoke upon temple building, the work to be done in the temples and the necessity of their gathering all that they could about their ancestors.

[At 2 o’clock meeting] I led them to believe that if they did so [lived lives of purity] and exercise faith the lord might move upon his servants, the prophet, Lorenzo Snow, to authorize one of his servants to seal wives to husbands for time and eternity. I felt led to touch upon this point for I believe if that were done here in the cases of faithful saints it would be attended with excellent effects.[15]

George Q. Cannon, First Counselor in the First Presidency, greets Church members in Honolulu in 1900. Among the first missionaries in the Hawaiian Islands, Cannon lauded the Saints’ faithful longevity. Courtesy of the William R. Bradford family.

George Q. Cannon, First Counselor in the First Presidency, greets Church members in Honolulu in 1900. Among the first missionaries in the Hawaiian Islands, Cannon lauded the Saints’ faithful longevity. Courtesy of the William R. Bradford family.

President Cannon went on to explain that he had spoken so freely to the Hawaiian Saints about receiving temple ordinances because during his visit he had observed firsthand the faithfulness of the Hawaiian Saints, some of whom had been “steadfast in the truth” for over forty years.[16] Such righteous longevity well exceeded that of most Church colonies established throughout the West.

However, President Cannon’s recorded statements do not say that a temple would be built in Hawaiʻi, only the possibility that the sealing ordinance would be made available.[17] That he did not publicly mention the building of a temple is explained by comments President Woolley made nineteen years later at the Laie Hawaii Temple dedication. Woolley stated that during his visit to Hawaiʻi in 1900, President Cannon specifically told him there would be a temple erected in the islands in the near future and that if not for that he would exercise his authority to seal some of the faithful Hawaiian families whom he had known for nearly fifty years. Woolley added that he had been deeply encouraged by President Cannon’s words and that since that day in 1900 he had dreamed of a temple in Hawaiʻi and actively labored to bring about conditions favorable to its accomplishment.[18]

As a result of President Cannon’s visit, temple work became a recurring topic at mission conferences, and Hawaiian Church leaders stressed to the members the personal worthiness necessary to qualify for temple blessings.[19] Even children in the Church school in Lāʻie were taught by their missionary teachers to “be good and go to church” so a temple could be built.[20]

Presidency of Joseph F. Smith

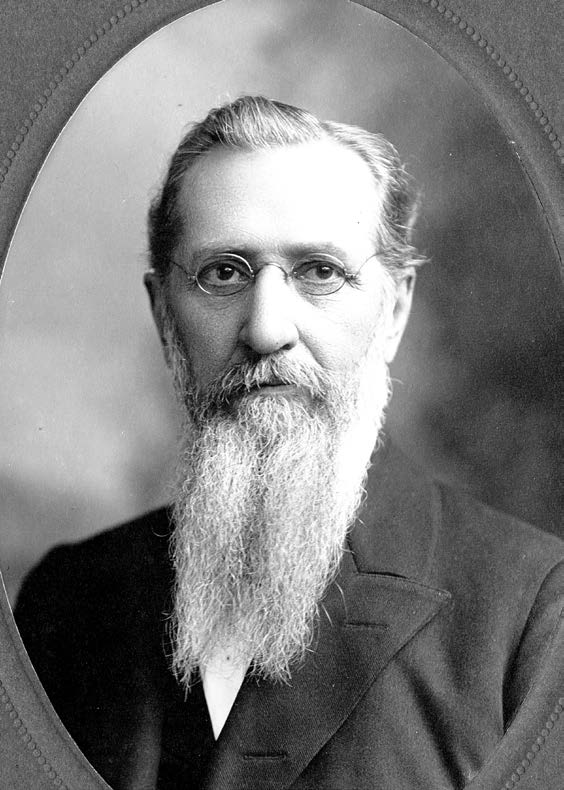

After almost a monthlong stay in Hawaiʻi, President Cannon returned to Utah in January 1901. As evidence that Cannon’s desire to extend temple blessings to more members was shared by his associates in the First Presidency, less than three months later President Joseph F. Smith, Second Counselor in the First Presidency, shared the following in general conference:

[Members] are becoming so numerous in distant parts of the country that even though we have four temples [St. George, Logan, Manti, and Salt Lake] . . . there are thousands of our people who are practically deprived of the privilege of enjoying them, because they are so far removed from them. Under these circumstances, I foresee the necessity arising for other temples or places consecrated to the Lord for the performance of the ordinances of God’s house.[21]

Becoming Church President in 1901, Joseph F. Smith continued to speak of the need for more temples to bless members far removed from Utah. Photo by C. R. Savage courtesy of Church History Library.

Becoming Church President in 1901, Joseph F. Smith continued to speak of the need for more temples to bless members far removed from Utah. Photo by C. R. Savage courtesy of Church History Library.

This statement signaled optimism that more temples would be built in order to serve those members living far from the geographic center of the Church. Sadly, just days after President Smith’s comments, President George Q. Cannon passed away (12 April 1901), and six months later, just four days after the October 1901 general conference, President Lorenzo Snow also died. A week later, on 17 October 1901, Joseph F. Smith, who cumulatively had spent nearly seven years among the Hawaiian Saints, was set apart as the sixth President of the Church. He would serve in that capacity for seventeen years.[22]

As prophet, President Joseph F. Smith continued to address the need for more temples, stating in the October 1902 general conference, “We hope to see the day when we shall have temples built in the various parts of the land where they are needed for the convenience of the people.”[23] However, the Church continued to face lingering political challenges[24] and debt, and President Smith’s public statements about temples seemed to subside over the next couple of years. Then in 1906, he declared that “temples of God . . . will be reared in diverse countries of the world.”[25] And in the April 1907 general conference, President Smith announced, “Today the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints owes not a dollar that it cannot pay at once.”[26] The Church was out of debt.

A Temple in Canada

In a surprise announcement in the October 1912 priesthood session of general conference, President Joseph F. Smith said that a temple would be built in Alberta, Canada. This concluded thirty-six years without the announcement of a temple, the longest in this dispensation, and seemed to signal that a new era of temple building had begun.

In general, Church persecution had receded and financial obligations were now met. The current prophet, Joseph F. Smith, who had a deep connection with Hawaiʻi, had repeatedly expressed his desire that temples be built in areas distant from the Church center, and the announcement of a temple in Canada was a step toward making this desire a reality. Certainly the optimism that a temple would one day be built in Hawaiʻi had never been more justified.

Notes

[1] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1881), 3:372. Succeeding prophets similarly taught of more temples to come: Wilford Woodruff declared that temples would be built across “North and South America—and also in Europe and elsewhere” around the world (Journal of Discourses, 19:229–30). And speaking at the dedicatory services of the Salt Lake Temple on 6 April 1893, President Joseph F. Smith said, “This is the sixth temple [including the Kirtland and Nauvoo Temples], but it is not the end.” Quoted in Brian H. Stuy, comp. and ed., Collected Discourses Delivered by President Wilford Woodruff, His Two Counselors, the Twelve Apostles, and Others, 5 vols. (Burbank, CA: B. H. S. Publishing, 1987–92), 3:279; and “The Ministry of Joseph F. Smith,” in Teachings of Presidents of the Church: Joseph F. Smith (Salt Lake City: The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2011), xi–xxv.

[2] The thirty-six years between the announcements of the Logan Utah Temple (1876) and the Alberta Canada Temple (1912) is the largest gap between temple announcements in the history of the restored Church. This era also produced the largest gap (twenty-six years) between the dedication of the Salt Lake Temple (1893) and the dedication of the Hawaii Temple (1919). See https://

[3] For an overview of challenges faced during John Taylor’s presidency, see Church History in the Fulness of Times, Student Manual, 2nd ed. (Salt Lake City: Church Educational System, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 2003), 422–34.

[4] For an overview of the conditions leading to the Manifesto, see Church History in the Fulness of Times, 435–50.

[5] Official Declaration 1, “Excerpts from Three Addresses by President Wilford Woodruff Regarding the Manifesto.”

[6] “The Church went about $300,000 in debt as a direct result of the Edmunds-Tucker Act. It had also undertaken the care of the families of men incarcerated for plural marriage, as well as their legal fees and court costs and its own legal expenses. The building of the Salt Lake Temple, the increased needs of Church education and welfare expenditures, and start-up costs of various industries added to the large debt.” Church History in the Fulness of Times, 454.

[7] Lorenzo Snow, set apart as the fifth President of the Church on 13 September 1898, died on 10 October 1901.

[8] In addition to the increased emphasis on tithing, the Church also purchased interest in a number of businesses to help provide additional resources to fund its operations. See Thomas G. Alexander, Mormonism in Transition: A History of the Mormons 1890–1930 (Chicago: University of Illinois Press, 1986), 74–92; and Richard O. Cowan, The Latter-day Saint Century, 1901–2000 (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1999), 38.

[9] See Royden G. Derrick, Temples in the Last Days (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 20.

[10] See William G. Hartley, “Coming to Zion: Saga of the Gathering,” Ensign, July 1975, 14–18.

[11] Millennial Star, 23 May 1907, 329. “He [Joseph F. Smith] and his Counselors in the First Presidency counseled members to be ‘faithful and true in their allegiance to their governments, and to be good citizens,’ and to ‘remain in their native lands and form congregations of a permanent character.’ Members of the Church were no longer encouraged to move to Utah to gather with the Saints.” Quoted in “Ministry of Joseph F. Smith,” xx.

[12] Riley M. Moffat, Fred E. Woods, and Jeffrey N. Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2011), 68.

[13] Andrew Jenson, comp., History of the Hawaiian Mission of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 6 vols., 1850–1930, photocopy of typescript, Joseph F. Smith Library Archives and Special Collections, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, Lāʻie, HI, 23 December 1900. See Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 106.

[14] Samuel E. Woolley Diaries, 23 December 1900, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, UT (hereafter CHL).

[15] George Q. Cannon, Journal of Travels to the Hawaiian Mission Jubilee, 30 December 1900, CHL, 16.

[16] Cannon, Journal of Travels to the Hawaiian Mission Jubilee, 30 December 1900, 16.

[17] First Presidency authorization to use the sealing power to solemnize marriages outside the temple for “those who are unable, through poverty or some other serious impediment, to go to the Temple of the Lord to be sealed for time and for eternity” had been a consideration for some time before President Cannon’s visit to Hawaiʻi in 1900. See Devery S. Anderson, ed., The Development of LDS Temple Worship, 1846–2000: A Documentary History (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 2011), 87–88, citing Wilford Woodruff to John Henry Smith, 21 September 1891.

[18] See Rudger Clawson, “Impressive Dedicatory Service and Prayer in New Hawaii Temple: Full Text of Dedicatory Prayer by President Heber J. Grant,” Deseret Evening News, 13 December 1919. See also N. B. Lundwall, Temples of the Most High (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1966), 153.

[19] See Moffat, Woods, and Walker, Gathering to Lāʻie, 106; and R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaiʻi, 2nd ed. (Lāʻie, HI: Jonathan Nāpela Center for Hawaiian and Pacific Islands Studies, Brigham Young University–Hawaii, 2018).

[20] Ruby Enos, interview by John Fugal, Lāʻie, HI, 1990, quoted in Richard J. Dowse, “The Laie Hawaii Temple: A History from Its Conception to Completion” (master’s thesis, Brigham Young University, 2012), 53, https://

[21] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1901, 69.

[22] See “Ministry of Joseph F. Smith,” xi–xxv. Further, Joseph F. Smith biographer Francis M. Gibbons noted: “Little if any time was required to acquaint the new president with the requirements of his office. For thirty-five years he had been one of the inner circle of Church leaders. He had served as counselor to the four previous presidents (Brigham Young, John Taylor, Wilford Woodruff, and Lorenzo Snow), and he had served with the last three throughout their presidencies. Moreover, his knowledge of Church leaders and doctrines extended to the earliest days of the Church.” Francis M. Gibbons, Joseph F. Smith: Patriarch and Preacher, Prophet of God (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1984), 216.

[23] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, October 1902, 3.

[24] Among the lingering challenges were the politically charged Senator Reed Smoot hearings. See Church History in the Fulness of Times, 465–79.

[25] “Das Evangelium des Tuns” [The gospel of deeds], Der Stern, 1 November 1906, 332, quoted in Church History in the Fulness of Times, 481–94.

[26] Joseph F. Smith, in Conference Report, April 1907, 7.