Faith and Community: Women of Nauvoo

Carol Cornwall Madsen

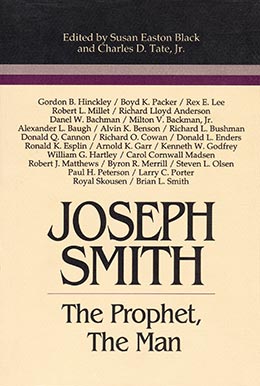

Carol Cornwall Madsen, “Faith and Community: Women of Nauvoo,” in Joseph Smith: The Prophet, The Man, ed. Susan Easton Black and Charles D. Tate Jr. (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1993), 227–240.

Carol Cornwall Madsen was associate professor of history and research historian, Joseph Fielding Smith Institute for Church History, Brigham Young University, when this was published.

After the Saints’ expulsion from Missouri, the new Zion, Joseph Smith declared in 1839, was to be established on a promontory of Illinois land, then known as Commerce, nearly surrounded by a bend in the Missouri River. The swampy land on the river’s bank—the flats, as they were called—gave rise to a plague of disease and death that almost sank the venture before it hardly began. And yet they streamed into the new city from all directions, believers, who, Eliza R. Snow observed, “seemed to have been held in reserve to meet the occasion, for none but Saints full of faith, and trusting in the power of God could have established that city” (Snow, “Sketch of My Life” 12).

Nauvoo was a city of refuge to those escaping the Missouri persecutions, a city of hope to the spiritually and economically impoverished British Saints who almost doubled the population, and their city on a hill for the spiritually hungry religious seekers from the East and Canada. But above all, Nauvoo was the City of Joseph, named for the prophet whose latter-day revelations drew these disparate people together and united them as Latter-day Saints. “I was willing to come and gather, “declared Jane Manning James, because “I was certain he [Joseph] was a prophet . . . . I saw him back in Connecticut in a vision, saw him plain and knew he was a prophet” (“Joseph Smith, The Prophet” 16:553).

Unlike the typical frontier town, Nauvoo was settled by families, a community as much dependent on women as men for its remarkably rapid development (James Smith 17–19!). Yet little is known about its women. Only three could claim instant name recognition today: Emma Smith, Eliza R. Snow, and Sarah M. Kimball, none of whom was truly typical of the man y other women who also made Nauvoo their home. These others, whose names lay hidden in diaries and journals, were also engaged, though less visibly, in the process of kingdom building, having committed themselves at conversion, like Priscilla Staines, to lay their “idols upon the altar” and “set out for the reward of everlasting life, trusting in God” (Tullidge 288). The hardships they encountered did not deter them in that commitment. Like so many others, Mary Field Garner, who lost a husband and two children after reaching Nauvoo, entertained no thought of abandoning her resolve. “We were too thankful,” she wrote, “to be at Nauvoo with the other Saints of God, and to be associated with our Prophet and leader, Joseph Smith, and to listen to his teachings . . . to complain about our problems” (Garner, “Autobiography”). In their personal narratives, the experiences of women take on a life of their own, telling a tale of the unfolding of a distinct and significant Mormon women’s culture tightly interwoven with the dramatic events and revelations making the final years of Joseph Smith’s ministry.

Though seemingly preoccupied with the continuous challenge of housing shortages, scarcity of commodities, and ubiquitous disease, the women’s writings are predominantly religious narratives, recorded accounts of the lives mandated and justified by the spiritual epiphany that brought these women to Nauvoo. It is as though in the recital of their daily struggles they gave testimony to the greater truth that informed their lives. They were part of a movement larger than themselves, and a prophet was at its head. Thus it is that in the presence of so much adversity they wrote accounts remarkably free of self-pity or regret. “I did not put my hand to the Plough to look backward,” Electa C. Williams responded when her husband’s parents offered a home and security if they would return to Michigan (Williams, “Autobiography”). For her, the time of decision was past.

Faith in the reality of the restoration and Joseph Smith’s prophetic calling had brought them to this gathering place despite its inhospitable environment. Adversity seemed to nurture their faith and create a tightly woven society, self-defined and distinct. These new Mormons were not building jut a city-they were building Zion and everyone had a part.

Sharing was the law of survival in Nauvoo’s earliest days. Finding food and shelter in a settlement that offered little of either spurred individual resourcefulness and communal interaction. The discomfort of crowding two fatherless families into a single room yielded to companionship and pooling of resources that sustained Sarah Pratt and Leonora Taylor in the absence of their husbands during Nauvoo’s earliest years of settlement. Despite a frenzy of building, housing could not keep up with the demand. British immigrant Ellen Douglas felt blessed to find a small house to rent when she arrived with her family in 1842, since she had “prayed that we might have one to ourselves for there is [are] 3 or 4 families in one room, and many have to pitch their tents in the woods, or any where they can, for it is impossible for all to get houses when they come in for they are coming in daily” (Letter).

Adequate housing was just one challenge women faced. Learning how to stretch a little cornmeal or a handful of greens to feed a family of hungry children was another. Mary Garner managed to keep her family of seven alive with only a pint of corn mean a day while Louisa B. Pratt sold her silver teaspoons for a bushel of apples (Carter, Heart Throbs 8:228). Women often traded their domestic skills for needed provisions. Drusilla Hendricks took in sewing and washing for food and reluctantly went out “on public days” to sell her homemade gingerbread, “this showing,” she wrote, “that necessity is the mother of invention” (“Historical Sketch” 24). Trading-a spool of fine cotton for a piece of pork, a blanket for a sack of flour, or a son’s labor for a cow—was the economic exchange in early Nauvoo, most of it done by women; bartering had long been “woman’s business” and scarcely required cooperation.

Sickness was a rite of passage for all newcomers to the city. Each week the Nauvoo Neighbor published the names of those who had succumbed to the deadly malaria, which struck every fall, along with a litany of other ailments that attacked the populace. (For a detailed analysis of the subject f death and disease in Nauvoo see M. Guy Bishop, et al.) As traditional caregivers women carried much of the burden of these debilitating diseases often while suffering from their destructive effects themselves. “We are now a family of invalids,” Sarah Allen exclaimed when she followed her husband and children into the sick bed, her body shaken with chills and fever. “It was very difficult to hire a nurse,” she found, “and as difficult to keep one on account of so much sickness, so I had to be my own nurse” (Carter, Our Pioneer Heritage 11:138). Immigrant Mary Ann Maughan scarcely had time to unload her luggage before she was called to nurse the Kingstons and Pitts, fellow saints from England who were suffering from the ague (Ibid 2:363). When her husband was bedridden from the complaint for a year, Mary Ann claimed that it “was the hardest one of my life, as I had to provide for a family of eight in the best way I could (Ibid 2:370). Even Charlotte Haven, a critical gentile visitor to Nauvoo, acknowledged the selfless service of two Mormon midwives who attended the birth of her nephew. “A kind heart in this place,” she observed, “can always be active” (Haven 622–24).

For many, the heartbeat of Nauvoo centered on the river that brought the streamers to the city and took them away again. Their freight was sustenance for the burgeoning city, but their human cargo was its life. The return of long-absent missionaries, the reunion of families, and the enthusiasm of new converts made the docks scenes of joy and expectation. New convert Mary Alice Lambert was thrilled to recognize the Prophet Joseph as her boat pulled into one of the docks. “I knew him the instant my eyes rested upon him, and that moment I received my testimony that he was a Prophet of God” (“Joseph Smith, The Prophet” 16:554). But even as the Nauvoo wharfs heralded seasons of joy and reunion, they also signified periods of loneliness, the partings, some permanent, engraving their images on saddened hearts. The wharf at the end of Water Street was inked in the memory of Emmeline B. Harris [Wells] when she said goodbye to her husband of little more than a year as he boarded a boat to go “downriver” to find work. She little dreamt she was bidding him goodbye forever. “Here I was brought to this great city by one to whom I ever expected to look for protection,” she wrote a few months later, “and left dependent on the mercy and friendship of strangers” (Diary, 20 Feb 1845).

The features most distinguishing the experiences of Nauvoo women from other women of their time were the unique principles and practices of Mormonism. More compelling than the demanding rituals of daily living was their immersion in the life of the spirit. The frequent prayer or blessing meetings that gathered families and neighbors together in each other’s homes intertwined the religious with the familial. “I never missed a meeting when it was in my power to go,” Elizabeth T. Kirby recalled, remembering especially the prayer meeting when “Sister Wheeler sang in tongues and the gift of interpretation was given to me” (Heward 13). Non-Mormon Charlotte Haven attended several of these Sunday evening cottage meetings and found each time “the room well filled” and the meetings “orderly” though unstructured, everyone “at liberty to speak” (Haven 627).

Women developed strong spiritual “kinships” as their everyday lives, in which they formed close, sustaining networks, merged seamlessly with their religious one. Spiritual manifestations, as experienced by Elizabeth Kirby, were frequent though quiet demonstrations of a unity of faith, expressed not in grand religious edifices or settings but in the private sanctuary of their homes among friends. Their dependence on faith endowed the most homely act with a supernal significance. Healing blessings, in the presence of untreatable illness, were a logical recourse, and women in performing their traditional healing art utilized this restorative power. Elizabeth Ann Whitney and Patty Sessions were only two of several women set apart by Joseph Smith “to administer to the sick and comfort the sorrowful,” and were often called into service (Whitney 7:191). Abigail Leonard drew on this reserve force of spiritual power when she called in the sisters to administer to a young British convert with whom she shared her home. “They came, washed, anointed, and administered to her,” Abigail wrote, noting that the young woman’s health was almost immediately restored (Tullidge 149). Drusilla Hendricks also trusted woman’s spiritual access. Unable to find provisions for her destitute family, she decided to travel to St. Louis to work and buy supplies. When others advised against her plan, Drusilla turned for counsel to Mother [Elizabeth Ann] Whitney because “I knew,” she noted, “she had had her endowments.” [1] In blessing her, Elizabeth Ann told Drusilla to go, promising her success in her efforts. After eight successful weeks in St. Louis, Drusilla returned with food, clothing, “and other comforts” for her family (“Historical Sketch” 25).

The slowly rising temple also merged the temporal and spiritual. Not only was it becoming a visual focal point of the flourishing city, as it rose high on the bluffs overlooking the river, but even more it was the spiritual focus of the people. Everyone had a stake in its completion. As men took their turns building it, women contributed clothing for the workers and their families, shared their homes with the builders, and offered tithes and other contributions. Many women, Louisa Decker remembered, “sold things that they could scarcely spare” to get money toward its construction, her mother selling her best China dishes and fine bed quilt “to donate her part” (Decker 37:41–42). Widow Elizabeth Kirby gave the only possession she had for which, she said, she would grieve to part, her husband’s watch. “I gave it,” she explained, “to help the Nauvoo Temple and everything else I could possibly spare and the last few dollars that I had in the world, which altogether amounted to nearly $50” (Heward 13).

But it was what would transpire within the temple they helped build that most distinguished LDS women from their Gentile counterparts. As introduced by Joseph Smith, the temple ordinances—the most sacred of their faith’s rituals—required women’s participation. Not only would they experience the sealing powers of the priesthood, linking husbands and wives in eternal marriage and binding families together from generation to generation; [2] not only would they make the covenants and receive the keys that would lead them to exaltation, but they would themselves perform their portion of those saving ordinances, officiating at the temple alongside their brethren. [3] Emma Smith was the first woman to receive the temple ordinances. She, in turn, administered the initiatory rites to other women, including Bathsheba W. Smith, who felt privileged afterwards to be “led and taught . . . by the prophet himself who explained and enlarged wonderfully upon every point a they passed along the way” (Smith Diary). Emmeline Wells noted that when the Nauvoo Temple was completed “woman was called upon to take her part in administering therein, officiating in the character of priestess.” One of these women was Eliza R. Snow who ministered in the temple “as priestess and Mother in Israel to hundreds of her sex” (Snow, “Pen Sketch” 9:74). Thirty-six women became ordinance workers in the Nauvoo Temple, working round the clock during the winter of 1845–46 to administer the ordinances to as many as possible before the exodus. “I worked in the Temple every day without cessation until it was closed,” recalled Elizabeth Ann Whitney, one of the thirty-six. “I gave myself, my time and attention to that mission” (7:191). Dozens of other women washed the clothing and prepared the food that physically sustained that remarkable undertaking.

Elizabeth Ann Whitney’s pleasure in temple service was exceeded only by the joy she felt in giving birth to the child who, she explained, was the first to be “born heir to the Holy Priesthood and in the New and Everlasting Covenant in this dispensation.” Having been sealed to her husband by the Prophet Joseph just a few months before, Elizabeth Ann treasured the knowledge that her daughter was the first child to receive this cherished birthright in this dispensation (Whitney 7:191). [4]

Adding to the rich spiritual dimension of the lives of these Nauvoo women were their patriarchal blessings. Personal and individualized, they were yet universal in their spiritual empowerment, declaring to the women their royal lineage and assigning them specific tasks and privileges. Like the revelation give to Emma Smith in 1830 (D&C 25), these blessings charged women to “teach, instruct, and counsel.” [5] Elizabeth Barlow Thompson was just one of the many women who were promised all of the “blessings of mother Sarah of old.” She was given “a renewed gift of wisdom, knowledge, light and understanding” and told “many will come to thee for counsel and advice and they shall go away happy and contented.” As a woman close to the spirit and willing to extend the reach of her nurturing, she was promised that she would “have great influence with thy sex for good . . . the young and rising generation [shall] come to thee for advice and instructions and thou shalt bless them and they shall bless thee” (Thompson). The spiritual relationship among women delineated in these blessings did not end in Nauvoo. A few years later Martha Riggs, like many others, was blessed that she would “become mighty in the midst of thy sisters . . . and thou shall have a knowledge by which thou shall teach the Daughters of Zion how to live, for it shall be required unto thee from the heavens” (Riggs). She was also promised prophecy and revelation. Besides receiving gifts of wisdom, knowledge, and light, women whose family ties had been severed at their conversion found solace in the knowledge that they would “stand as a savior in the midst of [their] father an mother’s house” (Ballantyne). Through the ordinances of the temple, they learned they would be the means of reuniting their families, a blessing unknown had they not been courageous enough to forsake their families in this life for eternal union in the next (see Thompson and Riggs; see also Ballantyne and Savage). Women were also charged with a duty to use their faith to heal the sick, rebuke the adversary, and discern evil for the benefit of their families (see Hall and Martin; see also Whitney 7:91, and Madsen). Nauvoo was indeed a community of Saints, men and women endowed with heaven’s power to bless one another’s lives.

The bonds of spiritual kinship that embraced the women of Nauvoo were strengthened and expanded on 17 March 1842 when Joseph Smith organized the Relief Society. “I have desired to organize the Sisters in the order of the Priesthood,” Sarah Kimball remembered his saying when she presented her proposal for a charitable society. “I now have the key by which I can do it,” he said. “The organization of the Church of Christ was never perfect until the women were organized” (Kimball). The Relief Society was thus perceived as more than a facility for charity. It was to be an integral part of the Church, giving women a distinct ecclesiastical identity. Like a spiritual magnet, the Relief Society drew women in ever increasing numbers, some even ferrying across the river from Montrose to attend its meetings (Williams “Autobiography”). Before its final session in 1844, its membership reached nearly 1,300. As an agency of Christian charity, it provided an institutional seal to the solicitude that already informed the relationships of the women of Nauvoo. Ellen Douglas was only one of many who experienced the fruits of this organized charity after the death of her husband. After 13 weeks of illness when she had been unable to sew or provide necessities for her children, she was encouraged to apply to the Relief Society for help. “ . . . They brought the wagon and fetched me such a present as I never received before from no place in the world. I suppose the things they sent were worth as much as 30 shillings” (Letter). The rapid growth of the Relief Society bespeaks their strong desire to preserve those relationships and to give definition to the strong female community of shared experience and belief.

Joseph Smith’s spiritually charged sermons to the members of the Relief Society instilled a powerful sense of their worth as women as well as Latter-day Saints. His broad vision of the woman’s rose in the restoration; his desire to make “of the Society a ‘kingdom of priests’ as in Enoch’s day—as in Paul’s day,” affirming its connection to the temple and the restoration of the priesthood; his delivery of the keys of knowledge and intelligence, both temporal and spiritual; and his approbation of their expression of the gifts of the spirit gave them a sense of full citizenship in the Restored Church (Minutes, 30 Mar 1842). [6] Nancy Tracy recalled the power of those sermons; “He was so full of the Spirit of the Holy Ghost that his frame shook and his face shone and looked almost transparent” (24–25). Whatever else it meant to the women, the Relief Society, along with the temple and their patriarchal blessings, gave them respite from the physical and emotional clutter of their everyday lives and offered them a transcendent vision of their part and potential in the great restorationist movement.

The prophet’s death, as his life, emerged as a rallying point for the faithful. Stunned by the news from Carthage, Joseph’s followers seemed transfixed in disbelief. “Every heart is filled with sorrow, and the very streets of Nauvoo seam [sic] to morn [sic],” wrote Vilate Kimball to her absent husband Heber (Esplin 238). The anguish of Louisa Follett, widow of King Follet, expressed itself in verse: “Oh Illinois,” she wrote, “thy soul has drunk the blood, Of prophets martyred for the Cause of God. Now Zion mourns- she mourns an earthly head. The prophet and the Patriarch are dead” (Follett Diary). The turmoil that followed the martyrdom drove out the disaffected and left a strong corps of saints “more united than before,” Zina Jacobs observed. The faithful are determined to keep the law of God, she affirmed, to finish the temple and claim “the blessings that had ben [sic] promised to us as a people by Joseph, A Man of God, and I believe after God’s own hard [sic]” (Beecher 298).

Joseph Smith in life was the cohesive force of the latter-day movement. In death, it was faith in the authenticity of his mission that preserved the unity and commitment of his followers. Their conviction sustained them in the tumultuous days that preceded their abandonment of his city and in their drive westward. They left behind a spiritually bereft city, “for the spirit of love and unity,” Mary Garner observed, “had gone with the Saints” (Garner “Autobiography”).

That spirit has been the energizing force in creating the bonds of community around Nauvoo women. Joseph Smith, in giving women an integral part in the Church and an essential role in its theology, strengthened those bonds and helped give definition to a distinctive type of religious woman. Though no longer gathered within the same geographic boundaries, LDS women today can find community in their shared faith and distinctive religious experience. They may not have known Nauvoo, but their religious roots are firmly embedded there.

Bibliography

Bishop, M. Guy, Vincent Lacey, and Richard Wixon. “Death at Mormon Nauvoo, 1843–1845.” Western Illinois Regional Studies (Fall 1986) 19:70–83.

Ballantyne, Anna. Patriarchal blessing by William Smith. Nauvoo, 1845, RLDS Church Archives.

Beecher, Maureen Ursenbach. “‘All Things Move in Order in the City’: The Nauvoo Diary of Zina Diantha Huntington Jacobs.” BYU Studies (Spr 1979) 19:285–320.

Carter, Kate B., comp. Heart Throbs of the West. 13 vols. Salt Lake City: Daughters of the Utah Pioneers, 1947.

Carter, Kate B.. Our Pioneer Heritage. 20 vols. Salt Lake City: Dauthers of the Utah Pioneers, 1959.

Decker, Louisa. “Reminiscences of Nauvoo.” Woman’s Exponent, (Mar 1909) 37:41–42.

Douglas, Ellen. Letter (2 Jun 1842) Nauvoo, IL. Typsecript. Martha Deseret Grant Boyle Collection. LDS Church Archives.

Esplin, Ronald K. “Life in Nauvoo, June 1844: Vilate Kimball’s Martyrdom Letters.” BYU Studies (Win 1979) 19:321–40.

Follett, Louisa. Diary. Typescript. LDS Church Archives.

Garner, Mary Field. “Autobiography.” Typescript. LDS Church Archives.

Hall, Abigail. Patriarchal blessing by Isaac Morley. 21 Mar 1846, Nauvoo, IL.

Haven, Charlotte. “A Girl’s Letters from Nauvoo.” The Overland Monthly [San Francisco] (Dec 1890) 616–38.

Heward, Elizabeth Terry Kirby. “A Sketch of the Life of Elizabeth Terry Heward” (6 Sept 1843). Parshall Terry Family History. Comp. Mr. and Mrs. Terry Lund. Salt Lake City, 1963. 13–15.

“Historical Sketch of James Hendricks and Drusilla Dorris Hendricks.” Typescript. LDS Church Archives.

“Joseph Smith, The Prophet.” Young Women’s Journal (Dec 1905) 16:548–58; 17:537–48.

Kimball, Sarah M. “Early Relief Society Reminiscences” (17 Mar 1882). Salt Lake Stake Relief Society Record, 1880–1892. LDS Church Archives.

Madsen, Carol Cornwall. “Mothers in Israel: Sarah’s Legacy.” Women of Wisdom and Knowledge. Eds. Marie Cornwall and Susan Howe. Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1990. 179–201.

Martin, Margaret M. Patriarchal blessing by James Adams. 7 Jul 184- (not clear). Bancroft Library, Univ of California at Berkeley.

Minutes of the Female Relief Society of Nauvoo. 28 Apr 1842. LDS Church Archives.

Oaks, Dallin H. “The Relief Society and the Church.” Ensign (May 1992) 22:34–37; also in Conference Report (Apr 1992) 47–51.

“Relief Society Conference, Juab Stake.” Women’s Exponent (1 Jun 1879) 8:2.

Riggs, Martha A. Patriarchal blessing by Zebedee Coltrin. 11 Nov 1876, LDS Church Archives.

Savage, Lydia. Patriarchal blessing by Patriarch Lorenzo Hill Hatch, Woodruff, Arizona, 31 Mar 1900, LDS Church Archives.

Smith, Bathsheba W. Diary. Typescript. LDS Church Archives.

Smith, Emma Papers. Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, Archives. Typescript copy in possession of author.

Smith, James E. “Fronteir Nauvoo, Building a Picture from Statistics.” Ensign (Sep 1979) 9:17–19.

Snow, Eliza R. “Sketch of My Life.” Holography. LSD Church Archives.

Snow, Eliza R. “Pen Sketch of an Illustrious Woman.” Woman’s Exponent (15 Oct 1880) 9:73–74. (This articles began in the 1 Aug 1880 issue [9:33–34]).

Thompson, Pamela Elizabeth Barlow. Patriarchal blessing by Patriarch Israel Barlow. N.d., LDS Church Archives.

Tracy, Nancy Naomi Alexander. “Incidents, Travels and Life of Nancy Naomi Alexander Tracy including Many Important Events in Church History (1816–1902).” Typescript. Brigham Young Univ, Provo, UT.

Tullidge, Edward W. The Women of Mormondom. New York: Tullidge, 1877.

Wells, Emmeline B. Diary. Special Collections. Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young Univ, Provo, UT.

Whitney, Elizabeth Ann. “A Leaf From an Autobiography.” Woman’s Exponent (15 Nov 1878) 7:91; (15 Feb 1879) 7:191.

Williams, Electa C. “Autobiography of Electa C. Williams.” In the papers of Emily Stevenson. Microfilm. LDS Church Archives.

Notes

[1] Before his death Joseph Smith administered the temple ordinances to a number of couples, fearing, correctly, that he would not live to see the completion of the temple. The Whitneys were among the privileged few.

[2] Widow Elizabeth Kirby worried that she “could not obtain her blessings as she was,” so decided that “the best thi8ng she could do” was to marry her husband’s hired hand, John Heward, who had come to Nauvoo from their native Canada to assist her when she joined the Church. With his assent they were married by Hyrum Smith (Heward 15).

[3] To a Relief Society conference in Juab Stake in 1879 President John Taylor explained this partnership: “Our sisters should be prepared to take their position in Zion. Our sisters are really one with us, and when the brethren go into the Temples to officiate for the males, the sisters will go for the females; we operate together for the good of the whole, that we may be united together for time and all eternity.” (“Relief Society” 8:2)

[4] Elizabeth Ann recalls the month as January in this account although family genealogy puts the date as 17 Feb 1844.

[5] A blessing given to Emma Smith in 1834 by her father-in-law reconfirmed the endowment of “understanding” and “power to instruct thy sex” (see Emma Smith Papers).

[6] Editor’s Note: For an alternative interpretation of what Joseph Smith mean in these remarks see History of the Church 4:570.

Since this paper was presented, Elder Dallin H. Oaks of the Council of the Twelve spoke on these events as he honored the 150th Anniversary of the founding of the Relief Society in General Conference: “The authority to be exercised by the officers and teachers of the Relief Society, as with the other auxiliary organizations, was the authority that would flow to them through their organizational connection with The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and through their individual setting apart under the hands of the priesthood leaders by whom they were called.

“No priesthood keys were delivered to the Relief Society. Keys are conferred on individuals, not organizations. The same is true of priesthood authority and of the related authority exercised under priesthood direction. Organizations may channel the exercise of such authority, but they do not embody it. Thus, the priesthood keys were delivered to the members of the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, not to any organizations” (Oaks 36).

As to the matter of the early women of the church laying hands on one another and bestowing blessings, Elder Oaks added: “In considering the Prophet’s instructions to the first Relief Society, we should remember that in those earliest days in Church history more revelation was to come. Thus, when he spoke to the sisters about the appropriateness of their laying on hands to bless one another, the Prophet cautioned ‘that the time had not been before that these things could be in their proper order—that the Church is not now organized in its proper order, and cannot be until the Temple is completed’ (Minutes, 28 Apr 1842, p.36). During the century that followed, as temples became accessible to most members, ‘proper order’ required that these and other sacred practices be confined within those temples” (Oaks 36).