Weaving a Tale (1824–1848)

T. Edgar Lyon Jr., John Lyon: The Life of a Pioneer Poet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 59–110.

On a summer’s morning in 1824, twenty-one-year-old John Lyon walked cautiously into the bustling town of Kilmarnock. He had taken a day and a half to cover the twenty-two miles from Glasgow, trodding along muddy roads, past green hills and dales, and greeting many cottage weavers on the way. Darkness had overtaken him in Fenwick, and where to spend the night was a serious problem. He stopped at a tiny wayside inn, but “I had no money to pay my night’s lodging. . . . [The innkeeper] asked me to leave something with her until I returned as a pledge. I gave her a new vest, until I should come back.” [1] Two weeks later, to her great surprise, Lyon returned to Fenwick, paid the lodging bill, proudly claimed his vest, and returned to Kilmarnock, his home for the next twenty-four years.

Lyon’s purpose in coming to Kilmarnock was to restore his lost health, but his most immediate concern was food and shelter—he would have to work, as well as “drink plentifully of sweet milk, and take all the fresh air morning, noon and night” (so said the doctor). He had never been so far from home in his twenty-one years and felt the usual insecurity and anxiety any stranger feels in a strange town. On the very morning of his arrival, however, he made inquiry and found a loom for hire, and after proving to its owner that he could indeed weave fine cloth, rented the apparatus as well as a tiny flat near the center of town. The day had been a success; by nightfall he exulted in the happy prospect of a regular job, a place to sleep, adequate food, and improved health. ‘“This was my first entrance into Kilmarnock, which became to me as sacred and more so, than Glasgow where I was born” (ms).

Kilmarnock was inhabited as early as the Roman domination of lowland Scotland. Here, or very near, Old King Cole, a local lord or chieftan, called for his pipe and his fiddlers three. Later, Marnock, an Irish monk, brought Christianity to the area, establishing a kil. Since the seventh or eighth century, the area became known as Kilmarnock. In 1821, Kilmarnock numbered 12,769 residents in 2,696 families. While 120 of the families engaged in agriculture, the remaining 2,576 were involved in manufacturing—weaving and shoemaking being the principal industries. The 2,696 families lived in 1,320 homes; there were only five unoccupied houses and only five under construction (M’Kay 238). In short, Kilmarnock existed with a housing shortage, heightened by the large families of the Industrial Revolution and little-remedied by infrequent new construction. The solution to providing for new residents seemed to be “move over and make room” rather than start a building boom.

In 1824, when Lyon arrived, the town would have numbered approximately 14,000 souls. Kilmarnock boasted a town library with nearly a thousand volumes. A newsroom in the town house subscribed to newspapers throughout the area and made them available to local readers. Printing presses produced books, but no newspapers were published locally. A joint stock company provided the very modern luxury of gaslighted streets, commencing service in 1823 (Kilmarnock and Riccarton Post Office Directory, preface). A building society, formed the same year that Lyon arrived, constructed a few nouses for its members, but by and large, crowded living conditions prevailed. A seventy-foot-high astronomical observatory added to the culture and sophistication of the town. Kilmarnock took pride in having published the first editions of Robert Burns’s poetry (1789) and considered him an honorary native son, even though he had lived in nearby Ayr. In 1823, the Philosophical Institution was organized for “‘the promotion of general, and more particularly of scientific knowledge” (M’Kay 310). The usual Presbyterian churches and offshoots conducted nine Sunday Schools in their stately buildings. Baptists, Roman Catholics, and Episcopalians completed the religious scene of the 1820s.

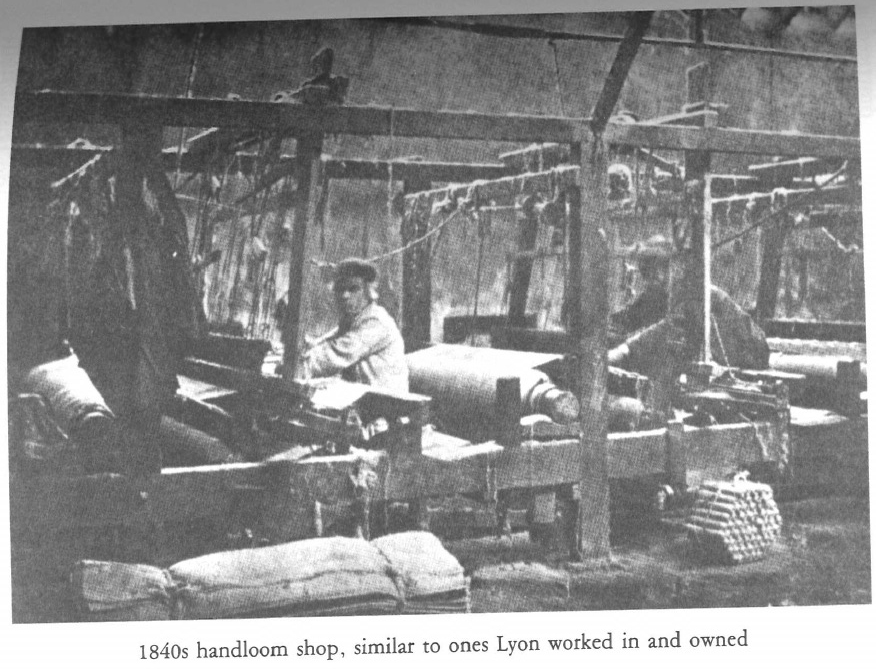

But it was not religion or cultural advancements which brought Lyon to Kilmarnock. He came to improve his health and his finances. In later writings he never again mentions weakness or dizziness; Kilmarnock was indeed good for his health. And in 1824 weaving in Kilmarnock was also in a hearty state. In this year William Hall introduced the printing of worsted shawls, providing work for those who printed the fabric as well as for hundreds of handloom weavers. Within a few years, three thousand looms turned out this new-to- Scotland luxury (M’Kay 239). In a one-year period in 1830 and 1831, more than a million shawls were produced in Kilmarnock. Carpets, rugs (blankets), and bonnets were also a vital part of Kilmarnock’s weaving output, but Lyon assuredly capitalized on the boom resulting from worsted shawls. Different from Glasgow, with a depressed, overcrowded weaving economy, Kilmarnock vibrated with life and opportunity. Experience gained in the tough-edged Glasgow market benefited Lyon such that he soon purchased his own equipment and enjoyed the mild prosperity of a successful young weaver.

Lyon missed friends and activities in Glasgow, so “on a very warm summer day in 1824, being then a young unmarried man, I started from Kilmarnock to Glasgow to see the fair, and to be social with my old comrades” (ms). He stopped at a country inn and pleasurably drank considerable “moor dew” to appease his walker’s thirst. Two sailors noted his fine appearance, followed him, beat him up, and took his bundle of extra clothing, which consisted of a “dress shirt, a silk vest, a pair of black, fancy ribbed stockings and a pair of new light buckled shoes.” Lyon had worn older clothes to walk in, saving the finer clothes for the fair. Having such a proper wardrobe after a few short weeks in Kilmarnock indicates that weaving had been profitable; he gave the appearance of elegance and prosperity, and for this reason the sailors mistook him for a wealthy fellow. As an experienced boxer, he undoubtedly gave them a good battle but could not prevail over two ruffians. He took a beating and returned to Kilmarnock without seeing friends or mother.

In 1824, the narrow streets of Kilmarnock not only bustled with new-found economic purpose but with hundreds of young lasses. Independent, hardworking Lyon, at twenty-one met, talked with, and courted several eligible young women. As a newcomer to the town, he passed through some difficulty being accepted by the “established families” but soon found favor with sixteen-year-old Janet Thomson and her parents, Janet Lamont Thomson and Robert Thomson. In the memory of one old resident, young Janet was a “Holm Lassie of much respectability.” [2] John talked of her as a “Holm Callan,” a young girl from the Holmes area south of town. The numerous Thomson families boasted a long history in the Kilmarnock area, achieving status and prosperity in various professions. After a few courting visits, ambitious, handsome Lyon enjoyed first the guarded acceptance and finally the full approval of the family.

Lyon family and LDS genealogical records indicate that on December 1 or December 4, 1825, John and Janet were married in Kilmarnock. He was twenty-two and she sixteen. The Kilmarnock Parish Registry, however, records no union between John and Janet in December 1825. Rather, on February 23, 1826, the registry reads, “John Lyon and Janet Thomson both in this parish, after proclamation were married” (Kilmarnock Parish Registry 597/

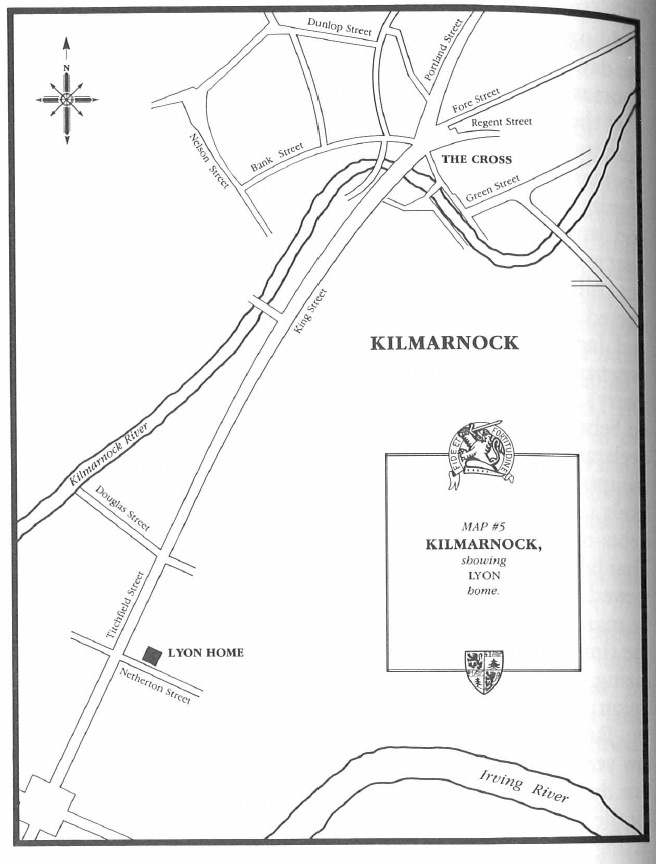

Janet and John probably lived with her parents for the first few years of their marriage; the prominent Thomsons had a fine dwelling south of Kilmarnock. But weaving required space for the awkward loom, so Lyon looked for a home of their own. Saving enough from the sales of woven goods, he put up money for a house on East Netherton Street, approximately one mile south of the center of town (see map 5). [3] No street number is mentioned in the post office directory—East Netherton was only one block long at the time, and its few residents were undoubtedly known by those in the vicinity Finally, for the first time in his entire life, Lyon had a house, a home, his own small castle. It was close enough to his in-laws that he often visited, but was removed enough that he was free to develop his own family traditions. He had proven that class barriers could be broken in industrial Great Britain: a young man from the sooty slums of Glasgow could work hard, marry a lovely, well-bred wife, and secure a fine home.

During the next twenty-two years, Janet gave birth to twelve children in this house, six boys and six girls, the last one born when Janet was thirty-nine. Eleven of the twelve children survived childhood maladies and lived past the crucial first year. Two others died while Lyon was serving a mission in England, 1849–51, and a third died shortly after his return to Scotland.

| Children of John Lyon and Janet Thomson | |

| Born | |

| Thomas | Sept. 5, 1826 |

| Janet | Jan. 5, 1829 |

| Annie | Jan. 6, 1831 |

| Robert T. | Dec. 15, 1832 |

| John, Jr. | Jan. 18, 1835 |

| Lillias | Aug. 22, 1836 |

| David C. | Nov. 3, 1838 |

| Matthew T. | Mar. 22, 1842 |

| Mary | Mar. 27, 1844 |

| Margaret | Dec. 15, 1846 |

| Agnes | Mar. 1, 1848 |

| Franklin D. Richards | Jun. 13, 1849 |

While children may be able to assist a family weaving endeavor as early as age six or seven, the first few years of their lives are more burdensome than profitable to business. Young Thomas, named for the paternal grandfather he never knew, tugged at the loom, played with the heddles, and likely misplaced a shuttle or two. As two sisters and then two brothers were born into the home, Thomas formed childhood alliances that at first hindered more than helped the weaving business. But soon he and his siblings were contributing members of the family business, filling the same tasks their father carried out as a child. The business stagnations, the demonstrations, and the exploitations in Glasgow were less harsh or absent in busy Kilmarnock. John and Janet “settled in” to a life of work and more work.

In 1827, after the birth of the first son, an event occurred which changed the entire pattern of Lyon’s life. He was a weaver, confident in his abilities to turn out a quality shawl, an excellent harness, or a tightly woven blanket. Yet this was not fully satisfying. Having had limited access to formal learning on two previous short-lived occasions, the twenty-four-year-old father now began attending the meetings of an intellectual fraternity in Kilmarnock. Identifying himself by the pseudonym of’ ‘Forest King” (Lyon—the king of the forest), Lyon recalls that he

became acquainted, however, with some spirited young men, and they forming a good opinion of him, introduced him to a Society they had formed during the winter vacation, as they were all College Students, and had formed this Society for their mutual improvement during winter.

In this Society Forest was taken notice of, particularly for his quaint remarks on the ideas suggested in their essays, and as every member, had this privilege, this gave great scope for argument, which brought Forest out, in his own natural remarks, very different from theirs. Although he had never been learned to write; except what he had got by reading his mother’s letters and words, and asking the meaning of them from boys at school, in this way he could scribble out all the words in the alphabet, and putting the words together, made out to him at least, that he could write a letter, which he did to his mother sometimes. In this Society the members had to produce some subject in turn. When it came to Forest’s, he was asked, by the president to name his essay, or the name of his piece so that the members might be able to respond to the sentiments or otherwise.

Forest, when asked the question hurridly [sic] answered, “The Devil,” more in the tone of a person surprised, than otherwise. The president who was an elderly gentleman professor, was offended, but when Forest said, that was to be his essay, it was put down, and such a winking and laughing there was among them, until called to order. If they had known that I could only scribble, and a poor hand at that, their fun would have been much greater, but from my remarks on their essays, and the design of cutting me up, they were pleased with the reflection, of what could I know of the Devil, and that I should find they would pay me back with good interest for my witty slang, as they called it. I did my best during the week, putting down every thing I had heard the Evil One accused of, as well all I had read of him in the Bible, and making my remarks thereon. Having closed my subject, I sat down to compose myself for a furious attack. But the respondent said he had never thought of such a character as that I had introduced, and left it to be discussed by the members without his remarks. But what was my surprise, any of them who did speak were perfectly nonplused, as they formed a very different opinion than I had. The president eulogized me and said it was the best treated subject he had heard during the session, and asked me to favor him with a rending of it; here was a dilemma. I had not thought of such a request; my writing resembled a sheet, as if a whole rookery of hens had walked over the paper. I told him I had merely scratched down my ideas, but I would draw out a fair readable copy, and present it next meeting night, which I did, having it translated from vulgar fractions, by a school boy, with my interpretations, to plain figures.

This essay I may say, brought me great respect, and I believe, none of them ever found out how ignorant I was. This was my first rise to the sublime, and put me on a determination to pursue my studies, which I did without a grumble night and day, while many of the students became my intimate associates for many years afterwards, and led me to friendship and places I never anticipated. (ms)

Whether this “Society” was the famous Kilmarnock Philosophical Institution or some lesser known organization is not clear. Whatever the group, they enjoyed Lyon and his witty, quaint verbal contributions. This “first entrance into literary society” indicates that Lyon was barely able to read and had not yet mastered the ability to write. He was conversant with the Bible, from his infrequent attendance at church meetings, but was not able to read it well. His bouyant personality and verbal acuity had carried him through his initiation, however. One of the members of the group, Matthew Wilson, recalled that “Lyon was of a forward, inquiring nature, very disputatious as well as pugnacious” (Senex, 1881, supplement). A more eulogistic—perhaps exaggerated—characterization appeared in the Millennial Star.

In the toils and struggles of early semi or complete orphanage he exhibited that drift towards intellectual pursuits, which was evidently hereditary, although it found none of those opportunities which come from schools; and disposition alone in the midst of grinding poverty enabled the little fellow to acquire from such resources as he could reach, the thirst for learning and advancement. (1889, 813)

Lyon’s own will, verbal facility, and fighting spirit impelled him towards more learning and successful literary activity. At age twenty-four he was clever with words, original and feisty, but he was not able to write well. Now, after presenting an innovative discourse on the devil, he urgently felt the need to write proper English. This single experience with “the devil” pushed him to improve and perfect writing skills to such a degree that for most of his adult life he was known as a writer first, then as a weaver. He studied “without a grumble night and day” in order to master writing skills; the process took several years, perhaps his whole life. Unfortunately, his first written exercise, the discourse on the devil, does not survive but would be interesting to compare to later writings. To master writing skills as an adult was tedious and frustrating for Lyon. Manuscript copies exist for many of his stories and poems, indicating that he felt the need to practice, polish, and rewrite before publishing a piece. The first drafts of his stories are almost always wordy and awkward, and at times filled with spelling errors and grammar problems; subsequent versions are improved greatly. Nearly every published story went through four or five drafts before it was ready for the public. To see his improvement, one need only compare the previously cited story of how Lyon got started writing, with its run-on sentences and illogical breaks, to the more polished prose of his published writings in Songs of a Pioneer.

Lyon’s drive to become a better writer eventually led him to begin writing for money. He and Janet continued and even expanded the weaving business, but as he developed and improved his writing skills over the next two or three years, he realized that he had a gift of expression, a talent that could turn a profit. He knew that neighbors and friends considered him clever, verbally adroit and witty; why not turn the aptitude into written expression? Could a living be made from writing? Kilmarnock had no local newspapers in 1828, but the success of Burns’s poetry still enlivened the air and many weavers dreamed and talked of fame beyond the web. Weaving could be an extremely social activity; it was not so mentally taxing as to fully occupy the Webster’s thoughts. Thus, he could converse, discourse, and even versify to the rhythm of the loom. The weavers of Glasgow had gained a reputation as political rebels because they took time to talk of societal malaise while at the loom; those of Kilmarnock also ventilated political frustrations, but the success of the worsted shawl and relative prosperity allowed many to dip into literature as an emotional outlet rather than into politics. Lyon saw opportunities and prepared himself. Janet was able to read and write; she may have helped him. He may also have taken formal training in the local Netherton Holm School, on East Shaw Street, just a block from the Lyon home. A new 36’ x 22’ addition to the school, completed in 1828, provided extra room for adult participation (Minute Book of Netherton Feuars, 1794–1952).

By 1830, John was able to write sufficiently well that he had some simple verses accepted by Ayrshire papers. However, he continued studying, meeting with younger college students, and attempting to improve his literary skills. He now had a goal—to write for the newspapers in the area. He would continue the family weaving business, with its periodic stagnations and irregularities, as well as write for newspapers, with all their irregularities and roving life-style. For the next eighteen years newspapering provided Lyon with identity, fulfillment in meeting hundreds of new and interesting people, and opportunities to travel. He did not secure a mighty fortune from the work, but what he earned was sufficient to supplement the weaving income. As with weaving earlier, newspapers were just coming into their boom period in the 1820s and 1830s. Previously, newspapers had been principally a large-town luxury; in the decade of the twenties small local presses popped up throughout Scotland, a phenomenon which persisted and multiplied until the 1860s, when the big dailies crushed and closed down the smaller papers. “There was then [1815–60] much more diversity of opinion and more real independence than is possible [now]” (Cowan ii). Newspapers, usually weekly, bimonthly, or monthly, were taxed at a high rate of four-and-a-half to seven pence per issue. Hence, they were not readily available to the poor working classes. Many papers existed by subscription and would-be receivers paid for a year in advance. During the 1830s, many unstamped papers defiantly challenged the newspaper Stamp Acts of 1819, such that the tax was reduced; nevertheless, Glasgow and other towns continued publishing radical, unstamped papers, most supporting reform and workers’ causes (Montgomery 154–69).

A fundamental principle governing most of the local papers was anonymity of authorship. Rarely did a contributor, even of an inoffensive literary piece, sign his name. “Anonymity was the rule and the press no stage for stunt features and personal display” (Cowan ii). Feature articles rarely carried names; original poetry was usually anonymous or appeared under a well-disguised pen name. A short story, “The Victim of Style,” which appeared in the 1835 Kilmarnock Annual, confirms this. It recounts the incident of an ingenuous local who made the innocent mistake of telling a friend that he wrote for newspapers. Soon the whole town knew; some felt that it was he who had slandered them in previous articles; others were offended because he did not write about them; the minister and teacher felt that they could detect his style in any contribution appearing in the paper. Finally the guileless fellow was forced to leave town.[4] This governing principle of anonymity is applied to Lyon; he too followed suit, contributing unsigned poems, stories, character sketches, news reports, and opinions to the local papers. A thorough search of the now incomplete newspapers he worked on has not revealed a single reference to John Lyon as author of an article or poem during the 1830s. Nor was the literary name he used later in life, Forest King, ever used to identify a contributor. For at least ten years, he wrote scores of pieces but his sought-for anonymity has proven most successful.

In writings of his later life, Lyon variously identifies himself as a “penny-a-liner,” a newsgatherer, a canvasser, a collector, a newspaper correspondent, and a traveling correspondent. He contributed to at least eight different papers. On occasion he worked for more than one paper at the same time. Lyon performed different functions for each paper. He traveled and sold subscriptions. He interviewed old characters in remote places and wrote accounts of their eccentricities. He delved into the history of a region and, in true Romantic fashion, embellished it with clouds, wild nature, and mystery. As a “penny-a-liner,” he collected local news and views and editorialized on their import, later calling himself “Lambda, the fill-up-a-corner-man.” And most of all, he observed the rural and working poor and frequently espoused their causes. He traveled, usually afoot, for weeks on end, during many of his twenty years of newspapership. Janet tended shop at home with the working children; Lyon walked and hitched rides all over Scotland. Lyon never made a complete work history and often used abbreviated titles or nicknames for the papers, but from his prose sketches, written later in life, it is evident that he worked with the following publications:

| Title | Years of Existence | Lyon’s Work on Paper |

| 1. The Ayr Advertiser | 1803–60 | 1829–30? |

| 2. The Kilmarnock Chronicle | 1831–32 | 1831–32 |

| 3. The Kilmarnock Journal and Ayrshire Advertiser | 1834–57 | 1834–40 |

| 4. The Witness (Edinburgh) | 1840- | 1840–42 |

| 5. The Ayrshire Examiner | 1838–39 | 1839 |

| 6. The Western Watchman and Ayr and Galloway Herald | 1842–44 | 1842–44 |

| 7. The Ayrshire Agriculturist | 1843–49 | 1843–48 |

| 8. The Kilmarnock Herald | 1844–48 | 1844–48 |

Some of these papers were monthlies; others were published weekly. Lyon could, therefore, work for more than one at a time since they were not always in direct competition. Nearly all of them advocated popular reform principles and the lessening of taxes and Tory control. The Witness and the Western Watchman had religious causes to advance as well.

Lyon’s later prose writings in America provide insights into his work and precise details on the characters and incidents he recorded from 1828 through 1848. Most of these stories appeared in the Deseret News during the 1860s. From these stories, one can piece together specific incidents in Lyon’s life during this period.

The earliest identifiable incident occurred (in late 1828 or early 1829) while George IV was still king (1820–30). Lyon indicates that he “was travelling as a canvasser for an agricultural newspaper,” likely the Ayr Advertiser (Songs of a Pioneer 158). While walking the western moorlands of Clydesdale, he noted an obtrusive, man-made mound, which piqued his curiosity. Pursuing his fancy, he went to a nearby house and met an old man who, by good fortune, had been a schoolmate with his grandfather sixty years earlier in Blantyre Parish. The white-haired farmer told John that the mound had been built as an observation spot to allow his ancestors, the Covenanters, to see approaching government troops coming to try to stamp out the Covenanters’ religious dissent. [5] The two men struck up an immediate friendship, and Lyon was invited to spend the night with the farmer and his family.

The apartment [house] to which I was introduced was their kitchen, dining room and workshop, where the women sat at their little spinning wheels working, while the old man, his two sons and myself, talked until bed-time on many religious and political topics. A great peat [turf] fire, with a piece of light coal blazing in the centre, gave heat and light, being aided by the reflection of a large rack of pewter plates on the opposite side of the room. On each side of the doorway was a large box bed, having for curtains sliding doors of wood. . . .

After supper, and before retiring to bed, the old man brought forth a large family Bible, and said, “Come, let us worship God.” He then opened the book and read two verses of a psalm which was sung by the whole family to the tune of “old hundred,” a chapter was read, and all knelt down, when the patriarch prayed fervently for the Almighty’s protection and favor—the rights of faithful men—the prosperity of Zion—the reign of peace to come, and for the true heritage of God, scattered o’er the earth. (Songs of a Pioneer 166–68)

After this family worship, Lyon and the old gentleman retired for the night, sharing the same cramped box bed. In the morning, the family repeated its scripture-reading and prayer, shared breakfast with the young newspaperman, and bid him stay another day; however, newspaper necessity forced Lyon’s immediate departure for Kilmarnock.

Several vital details emerge from this “first sally” into the world. Lyon was able to make friends easily, even with cautious, closed farmers whose ancestors had been suspicious of all strangers. The location is specified, Lochgoin, a farmstead near Fenwick. Dating the event is relatively easy since the author indicates that George IV was then his king. Lyon also mentions that the old farmstead was near the “birthplace of Robert Pollock, who had recently died.” Pollock was a folksy local poet who died in September 1827. Hence, the incident took place in 1828 or 1829- But the most important element in the story—and, indeed, in many other stories by Lyon—is the presence and power of religious conviction. He was fascinated by the strength and unity he observed in those with deep religious feelings, especially the Covenanters, the Dissenters, and all groups which provided a spiritual fulfillment to their adherents. Fully a third of the extant stories written about his newspaper years deal with the religious motif, long before he himself’ ‘took up the cross” and joined the Mormon church. At the time he met the Covenanters, John was apparently not participating in any organized church worship, a pattern carried over from his early life in Glasgow. Presbyterianism had at one time been the religion of his ancestors, as it was of most Scotsmen, but it had lapsed or lost its spiritual hold on John and his parents. His wife may have attended Sunday School in her native Kilmarnock, but religion was not a dominant part of their early married life. Perhaps the absence of a personal religious conviction aroused Lyon’s interest in those who confessed and professed an active creed. By 1829, John and Janet had two children, a further stimulus to question the direction of their lives and examine gaps in their spiritual commitment.

For some reason, perhaps either his inability to adequately convey the feeling in writing or his fear of censorship for writing on a controversial subject, Lyon never published in Scotland this experience with the Covenanters:

I left the place in fulness of my vocation as a reporter, to note down what I dared not then submit to the press, but which remains as the living memorial of rejected pieces, kept in the archives of memory and reflection till time and opportunity gave them a name and location in the world of letters. (Songs of a Pioneer 169)

Lyon was still attending a night school and

was ambitious to be a scholar, and to rise in the scale of learning, as I had composed several pieces of rhyme, and had some of them accepted in newspapers. I was determined to obtain a knowledge of the English language, so that I could write correctly for the press. [6]

These years of school as an adult proved a bit embarrassing for Lyon, a married man much older than the regular schoolboys. Nevertheless, he stuck with formal studies until 1830, at which time he felt that he had mastered the complexities of writing English. Some of his verses, now lost in anonymity, had been accepted in the Ayr Advertiser, but publishable prose contributions, other than short newspaper stories, were still only a hope for the future.

In 1830 or 1831, Lyon made a three-day “excursion to Loch Doon to give a description of the history and beauties of that place” [7]—the first newspaper assignment he mentions in his later writings. He had gained sufficient recognition by this time to be trusted by his superiors to turn out a good piece. He talked two local fisherman friends into joining him, and on a humid summer day they journeyed to the Ayrshire lake. They fished, drank, danced, partied, and talked to the locals. In what by then was a pattern of his newsgathering, Lyon sought out one of the older residents of the area, established rapport, and got the old man to relate personal stories. Lyon and his friends then journeyed to a nearby castle and passed through a picturesque glen, spending the rest of the daytime hours talking and fishing. In later writings, Lyon recalls the tasty trout breakfasts as well as the cheese and whiskey at night. The trip seems more like a vacation than work, but he did collect sufficient history and local color to “fill up a corner” of the newspaper. Years later, worrying that his Utah readers might judge the trip a frivolous lark, Lyon noted that he was “gathering scraps [for stories] by the way . . . asking subscribers for the paper and collecting back paper accounts, which was my real [emphasis added] business engagement.” In sum, he was not a sports editor assigned to check out the local fishing but merely an all-around worker for the good of the paper, involved with soliciting, selling, and collecting. While traveling with these primary purposes in mind, he also observed and scribbled down notes, eventually working some of them into human-interest stories.

On July 12, 1831, a third child, Ann, was born to the Lyons in Kilmarnock. Just as with the older brother and sister, no record of Ann’s birth or christening is found in local parish or midwife registries, an indication that the parents were not active church participants and that they were probably still struggling financially. The small family cottage on East Netherton Street now housed four-year-old Tommy; two-year-old Janet; the new baby, Annie; John and Janet; and the large weaving loom, still the main source of family income. Lyon was away frequently, and to Janet fell the burden of child rearing, as well as weaving. Lyon plied the loom when he returned home in the evenings. The Lyons were only two of the 1,200 people in Kilmarnock manufacturing worsted, printed shawls. “Between May 1830 and June 1831, there were 1,128,814 of these shawls manufactured, the value of which amounted to about 200,000” (New Statistical Account of Scotland 551). Despite the hours of labor required to produce each fine shawl, the depressed, oversupplied market now brought small financial gain to the steady workers. “Men, women and children work . . . six days per week, and most ten hours per day, and some twelve hours” (New Statistical Account 552). At times John and Janet worked even longer hours—seventy or eighty a week.

This hard life was joyously interrupted each Tuesday and Thursday by market days in Kilmarnock. Janet would often trade a handwoven shawl, bonnet, or blanket for agricultural produce brought from nearby farms. Different from many of his neighbors, Lyon never owned a cow in Scotland, so the family had to buy or trade for milk, cheese, and curds. They purchased tea, a miniscule amount of butcher meat, a few herring now and then, a taste of sugar, and many giant bags of oats. And they tended a small kailyard (family garden plot) near their home, where green vegetables grew large in the moist black soil and supplemented the ever-present diet of oats. Breakfast for the Lyons normally consisted of an abundance of porridge made with whey or water, no sugar, and mixed with milk. Oat cakes, cheese, and bread might complete the fare. Dinner, taken late in midday, consisted of a broth thickened with barley, peas, beans, and other garden stuffs. Beef or mutton occasionally appeared on the family table, supplemented by the never-ending oat cakes, or potatoes and milk. For supper they usually ate porridge and milk again, champed (mashed) potatoes, sowens (oatmeal pudding), and oat cakes when available. Choice and variety were limited, but the family grew and maintained adequate health.

As Lyon traveled in his newspaper work, he sold or bartered his own woven wares, always carrying a bundle or sack to deliver woven goods and return with foodstuffs. But to Lyon, his pen and notebook were still the most prized items carried in the pack. He composed verses, jotted down impressions, and carefully recorded colorful scenes and characters. Some of this local color appeared anonymously in the Ayr Advertiser, most remained unpublished in miscellaneous notebooks, destined to appear in Utah papers as “Scraps from the Note Book of an Old Reporter.”

One newspaper assignment took Lyon to the grounds of the nearby Dundonald family mansion to look into some rumored illegal activities. “One Sunday morning I put on a new suit of black clothes, that I might appear respectable.” [8] He walked the few miles to the mansion and met an old character, John Cochrane, or “Jack O’ the Whelps,” who lived in a large dugout near the manse. Cochrane mistakenly took Lyon to be a young doctor and invited him in, whereupon John observed other finely dressed young gentlemen, all involved in betting on cockfights, dogfights, and “drawing the badger.” Although the cruel activities sickened him, Lyon stayed the entire day, even after the betting guests had departed, and became a good friend with the unscrupulous proprietor. Cochrane provided Lyon with a meal of kale

composed of a boiled cow shank and a tongue or two, well seasoned with onions, cabbage and other vegetables. . . . The table was composed of rough boards, laid on trestles and the culinary vessels were brown delfware, tin and wooden “luggies,” or cups. The knives and forks were home-made, all of a piece [of wood] rough but clean, which to me was a wonder. (ms)

The betting, vulgarity, homemade whiskey, and animal violence exhibited during the day shocked young Lyon and caused him to compare the life of the well-dressed “gentlemen” with the humble but noble existence of the old Covenanters and the poor with whom he regularly associated. His sympathies quite obviously went with the latter. Sometime later he published the account of this day in the Advertiser. “It created quite a sensation among the authorities in Ayrshire. Policemen, excisemen, and other persons were on the alert to find the writer who dared to publish such a ‘romance,’ or falsehood on the religious people of that portion of the country” (ms). Anonymity in publishing continued to be a protective necessity.

In 1831, Lyon began occasional work with the new and fragile Kilmarnock Chronicle. The irregularly published paper, founded by James Paterson, lasted less than two years, but the period was enough for Lyon to firmly establish himself as a newspaperman in his own town. On November 5, 1831, the famed Italian violinist Niccolo Paganini made an unexpected stop in Kilmarnock. He had played in the nearby town of Ayr, and while returning to Glasgow, his traveling coach broke down in the narrow, winding streets of Kilmarnock. A local theater was opened to him, and he agreed to give a benefit performance for the poor. To the ruddy Scotsmen, Paganini was “weirdlike. He had, in fact, an unearthly appearance—so wan and spare—with muscles immovable” (Paterson 104). Lyon attended the performance and contributed a small piece to the floundering paper. Such human interest stories were now his specialty, filling small corners in the Chronicle and Advertiser.

The year 1832 was eventful for Great Britain, for Kilmarnock, and for Lyon. A cholera epidemic spread from continental Europe to England and moved with frightful rapidity to Scotland. From July to October of 1832, approximately 250 people died in Kilmarnock. A temporary hospital was set up in Ward Park, not far from the Lyon house, where some patients recovered, away from their fearful families. Many, however, did not recover and were buried with only the briefest ceremony in a mass grave in the corner of the park. Janet was pregnant during the epidemic; fortunately, she and her entire family escaped the ravages of cholera. Most families felt it.

To describe the state of terror into which the public mind was thrown would be a difficult task. Some, to avoid the danger, held no intercourse with society at large. Others changed their place of residence. . . . Many of the sufferers were persons of irregular and dissipated habits, such as were reduced to a state of extreme indigence by their own folly and want of circumspection. The temperate and virtuous also, it must be confessed, fell before the scourge, but not in the same proportion. (M’Kay 241)

Fortunately, Kilmarnock suffered only a small percentage of deaths; other towns in the west of Scotland lost a fifth or a sixth of their inhabitants; and the village of Inver in the north buried fully half of its population. The contemptuous tone of the above quote indicates that intemperance and dissipation were to blame for many of the deaths in Kilmarnock; in reality, the disease struck those who were already weakened by hunger or reduced to mean living by poverty.

The year 1832 also witnessed a great business recession or “stagnation” in Kilmarnock, with traditional trade coming to another of its irregular halts.

Not a cotton mill, print shop, bleachfield, or woolen factory but were shut up, and the hands sent adrift to find a living elsewhere, or starve if they could not. During this period thousands were parading the streets and crowding around the mayor’s residence, calling out for relief in no mistakable language.

It would be folly to describe the squalid destitution and misery which that short period brought to the homes of sober, industrious, and aforetime, respectable citizens. Faint efforts had been made by the authorities to stifle the cry of hunger in the shape of subscriptions. But the demands were so many, and daily accumulating, and the poverty so deplorable, that means could not be collected adequate nor fast enough to meet their necessities. (Songs of a Pioneer 315)

Lyon quite naturally followed the human interest stories of suffering brought on by unemployment and wrote various bits for the Chronicle. He was now sufficiently well known that the magistrates appointed him one of twelve men to dole out relief and report extreme cases of suffering. After several months a town councilor, whom Lyon names Craik in his later narration (likely the well-known Hugh Craig), asked John to draw up an accurate census of the poor in and around Kilmarnock. Lyon complied, detailing some of the worst cases he had observed, and just two days later handed the report to Craig. Three weeks later, in the Chronicle office, the editor thrust a copy of the London Daily Times in front of John. Lyon quickly glanced at the paper and recognized that his survey on poverty occupied four columns on the front page! Craig had sent it to London to Robert Wallace (of nearby Kelly), a popular and vigorous orator, who had read it in Parliament. No credit was ever given to its author; it was merely read and published as an anonymous report on suffering in Scotland. The same article appeared in the local papers but with negative official response, since the local magistrates felt that it reflected their inefficiency and even niggardly behavior toward the poor. They came to the paper, demanded to know who the author was, and threatened the staff. Anonymity and authorial privilege were again wisely maintained, and Lyon escaped censorship or worse. [9] Public officials were unaware, but his colleagues now knew his work. “I may say that this affair gave me a new start in the reporting business; often I had burned the midnight oil to produce a column of matter which ran ten chances to one of being rejected, but now the tables were turned and [I could get my] reports received with pleasure, and paid per charge” (Songs of a Pioneer 324). A single fortuitous incident set a course for the rest of his life; he would still weave at home, but weaving tales for the press was now his first vocation.

The year 1832 also saw the introduction of the first major voting Reform Act in Great Britain, an act calling for a redistributing of parliamentary seats to favor newly industrialized areas and extending to middle-class landholders the right to vote. In May, when the House of Lords at first rejected the bill and it appeared that it would not become law, the angered citizens of Kilmarnock held a protest meeting. Lyon, parading his already-manifested concern for politics and the poor, was present. Various politicians were hanged or burned in effigy. When the bill was finally passed, “the exultation of the people of Kilmarnock was extreme, nothing but bonfires . . . and fuddling [drinking]. . . . They were now to have a fifth share in a whole member of Parliament” (Paterson 105). So elated was Lyon that he penned and published a “Song of Reform,” verses to be sung to the tune of “Killiecrankie”:

In days when folks ken’d naught ava

About the kirk or state, man,

They thought it was their duty, a’

To beck and bow to great men;

But now the poor folks’ turned mair wise,

And may their knowledge higher rise

Till once the rogues wha did despise

The poor man’s fare, he brought to share

A carcass spare, and deeding bare,

Wi’ face as thin’s a slate, man.

We’ve stood amidst the thunder storm

Of tyrants’ mighty rage, man,

But unity has brought reform

Tae this enlightened age, man,

Though ance it was a mighty crime

To speak the truth, or yet combine,

And if we chanced at any time

Tae growl or grudge, or yet tae nudge,

They’d gar us trudge, and would us lodge

Securely in their cage, man.

But since we’ve got the rogues brought doon,

Wha kept us in the thraws, man,

We’ll drink a health a’ roun’ an’ roun’,

“Success tae freedom’s cause, man.”

And may ilk honest-hearted chiel

Be ready aye tae tak’ the fiel’

And steady stand wi’ hearts o’steel

To strike the blow at freedom’s foe,

And lay them low—it shall be so,

Never mair tae craw, man.

(Songs of a Pioneer 118–19)

Kilmarnock became the head, or the returning burgh, from which a new member of Parliament was to be elected and hence a much more politically active town than previously. Prior to 1832, voting privileges were enjoyed only by a few nobles, established upper class who owned property; now some power shifted to the newer middle class, and a very obvious conflict over the rights and privileges of the poor ensued.

For the next sixteen years, Lyon contributed poetry, prose sketches, news items, and local color to the Kilmarnock Journal, the Witness, the Ayrshire Examiner, the Western Watchman, the Ayrshire Agriculturist, and the Kilmarnock Herald. He never bought into the ownership of any of these papers nor aligned himself with a single editorial policy. Most of his writing, and indeed the slant of the papers, dealt with reform and the need to improve life and society. His newspaper experience gave Lyon identity as a writer, an intellectual, even a liberal. He frequently traveled to Ayr, Machline, Stewarton, Fenwick, and many nearby villages and farms. At times he went as far as Glasgow, East Kilbride, and Edinburgh. He wrote sketches, reported newsworthy events, canvassed for subscriptions, and carried out editor-assigned tasks. He continued his home in Kilmarnock but walked, hitched, paid a pence to ride a public coach, and, after 1842, rode the fast-moving new trains from Glasgow and Edinburgh. In Kilmarnock he associated with William Wallace, John Leighton, John Beaton, John D. Carrick, Matthew Wilson, James Paterson, James Mathie, Hugh Craig, and others. Years later, he satirized many of these men in his stories, using the thinly veiled names of Jinks, Bellows, Craik, Skelly, Tim Snissel, etc. Lyon obviously enjoyed the work, talking and writing with opinion-setters and elected officials, but he also found hypocrisy, pettiness, and deceit in the newspaper world. Many of his prose selections in Songs of a Pioneer—“Jinks and Bellows,” “In Search of a Lost Poem of Robert Burns,” “The Covenanter,” and “The Self-Made Chemist”—examine the newsgathering process, its trials and joys.

Lyon fortuitously embarked on a new career precisely during the period (1833–47) that R. M. W. Cowan considers “one of the most stirring in the history of the English newspaper” (134). The appearance of so many newspapers in Ayrshire during the 1830s and 1840s attests to the health of the newspaper industry during that period, and Lyon worked for nearly every one of them. The papers prospered during this period because they became more protective and less likely to be sued for libel. Also, in 1836 the stamp duty was reduced, first from seven to four-and-a-half pence per paper, then to one pence; and in 1855 the duty was abolished altogether. This made newspapers more accessible to the working but still poor middle class. Lyon fought vigorously for the reduction of the duty, arguing that it was an “illegal tax on knowledge.” Many smaller papers flaunted the government and simply ignored charging the duty; the larger papers for which Lyon worked generally followed government rules to avoid possible closure.

On February 7, 1834, Kilmarnock’s first successful paper, the Kilmarnock Journal and Ayrshire Advertiser was launched by editor John D. Carrick and was published by Messrs. H. Crawford and Son. It began as a joint stock company advocating reform principles but later became more conservative (M’Kay 244). The first edition affirms that it is “a new political journal [whose] creed is declared Liberal and, consequently stands opposed to all measures detrimental to . . . our civil and religious liberties.” From the articles in this issue, it is obvious the editors felt that England collected too many taxes and returned too few benefits. “As Scottish journalists we have duties to discharge . . . and we are determined to stand . . . in the ‘gude’ town o’ Kilmarnock as long as there’s a button on our coats.”[10] The paper carried advertisements for food, cabinetmaking, and fire insurance; Hugh Craig announced he had “much cloth to sell to the public.” The paper reported a meteor shower in the United States and offered snipping news, births, deaths, and information on the local weaver’s union. Most of the news stories were gleaned from other newspapers throughout Great Britain; local news was limited. To determine which journalists contributed which articles—the fledgling paper zealously guarded authorial anonymity—is impossible.

As personal conflicts developed on the staff and the Journal took a more conservative stance, Lyon found more satisfying employment with other newspapers. In 1839, he wrote for the short-lived Ayrshire Examiner, but no identifiable contributions exist. In 1840, he found a journal that best expressed his own personal views—the Witness, published on Wednesdays and Saturdays in Edinburgh. “Its purpose was to assist the cause of a ‘pure, efficient Christianity,’ such as had dignified the Covenanted Church” (Cowan 236). Its editor, Hugh Miller, contracted John to represent the journal in Ayrshire. Lyon’s fascination with religious dissent now found journalistic outlet as he crusaded for reform in the church, as well as the state. By 1842, he vocally rejected the conservative trend of his hometown Journal and devoted major efforts to the Western Watchman and Ayr and Galloway Herald (1842–44), another paper with a religious mission, supporting reformist and non-intrusion policies. Finally, in 1844, along with many political liberals, he aided in the formation of the Kilmarnock Herald (1844–48). During these same years of newspapering turmoil, he wrote and canvassed for the Ayrshire Agriculturist (1843–49). Each published piece brought a few pence to supplement the diminished earnings from family weaving. Lyon was now a full-time writer and only a part-time weaver.

Recalling his work for the Kilmarnock Journal, with its biased editors, Lyon states, “Although I never was a really smart reporter, yet I generally gave occurrences as they transpired, and that was something in a one-sided paper where accusation, insinuation, public abuse and scandal were the bone and sinew of its deformed existence” (Songs of a Pioneer 301). He may not have been a great reporter, but he excelled in description of local characters and places. Tommy Raeburn, a well-known eccentric near Kilmarnock, is delightfully drawn in black and white, smelling and dirty:

He was covered with what had been home-made blue cloth, but so patched with all sorts of colored rags that no one could distinguish, at a short distance, the original ground work. His hat was without a brim; his coat, vest, and pants were hanging in tatters like a sheep’s fleece ready for shearing. His shoes had been worn out and made into clogs; his legs were naked, and the uncombed hair of his head and beard hung down over his back and breast more than two feet, matted together like a batch of cow’s hair disgustingly besmeared. Tommy was a strong built person, over six feet in height broad shouldered and well formed; but such a figure of rags and filth I have never seen before nor since. A crowd followed him through the street keeping at a respectful distance as if he had been a bear let loose for their amusement. (Songs of a Pioneer 172)

Similarly, Lyon also “painted” one of the editors of the Journal in masterful prose:

His face was naturally long and narrow; his eyes protruded considerably, being very large, the color of which changed so often that I could not say of what they were composed; when he smiled they were yellow; when serious, green; when reflective, a dark hazel, such as I have seen in a cat. His nose was a masterpiece of Roman antiquity, rising in the centre like a drawbridge between his brow, and curved chin, which gutted out and upwards, leaving a small space, to the deep furrow of his mouth, which marked a cut three-quarters across the hollow cheek of his carnivorous visage. (Songs of a Pioneer 288–89)

A further example demonstrates his ability to capture detail and depict the feeling of a bar full of dissipated veterans:

To form a correct idea of this elysium of Mars, you must lay commonplace conjectures aside, and try to conceive, not a palace of ornament and grandeur, such as the halls of England, but a large, dingy room, divided into eight compartments or boxes, set with forms and tables, around which are seated groups of invalids, varying from twenty-six to seventy years of age, and, on the table before them, intermingled newspapers, broken tobacco-pipes, pewter quart tankards, and above their heads an atmosphere as thick as the fogs of Kent, issuing from the mouths of fifty patented sucking valves, sending forth their steam as the piston of their lungs forced out the exhaled smoke, to squirt out a stream of saliva or tell an anecdote of daring adventure. (Songs of a Pioneer 140)

Lyon was never well known in Kilmarnock as a major local poet; fame in this genre came later in his life while in Utah. He was, however, thought of as an excellent storyteller and accurate recorder of human interest events. His various editors continued to send him to distant parts of southwest Scotland to dig up a story, cover a regional celebration, or interview a local character. He was frequently away from home for two or three days each week to adequately experience and record his assignments.

During his years as a newspaper man, Lyon’s home and family grew. Child number four, Bobby (Robert Thomson), was born in the notable year 1832; John, Jr., in 1835; Lily in 1836; and David in 1838. And so in the late 1830s, John built an addition to the stone house on East Netherton Street to accommodate his expanding family. Unlike in many families in Kilmarnock, none of the Lyons’s first eight children died in infancy. All the children labored, tending the garden and each other, working, and weaving to assist the family income. During most of the year, Janet did the cooking in the fireplace, swinging a pot of porridge into the fire on a sweigh, or hook and chain. Until the invention of friction matches in 1833 and their later dissemination in the 1840s, she started a fire with flint and steel. Water for the house, always too scarce, came from a nearby well shared by several neighbors; baths and cleaning were very infrequent. Light for the expanded house was provided by candles and oil cruise lamps. The children slept in box beds that were built right into the walls and doubled as storage areas during the day; two, three, or four children may have shared a single bed. The concept of a private room for one or two children was unknown; the house belonged to all, and each worked to improve the lot of the family. From his own struggles and experience, Lyon determined that his children would have as much education as possible; he sent them to nearby Netherton Holm School. The children frequently missed school, however, when they were needed to work at home, but all learned to read and write at an early age.

The children delighted in the frequent special days—May Day eve with its fires was a thrilling time for all. New Year’s Eve and Day were filled with amusements, visiting Janet’s parents, and playing with cousins and neighbors. Christmas was not a day of festivity but only of religious worship. “But Hallowe’en the night when a’ the witches are to be seen” was the most magic of all (Haldane 46). Bonfires, guisers, and roasting nuts made it an annual pleasure anticipated for weeks by the children. Ginger cakes and gingersnaps were welcome treats, a change from the everyday oatmeal and oat porridge.

The Lyon children knew that they were weavers—they all participated with their mother and proudly showed off their skills when their father was home. Janet and John took in “customary” work on consignment from neighbors and local businesses. Despite the introduction of the power loom, handloom weavers still found plenty of specialty items:

There’s shirtings, sheetings, corduroys, nankeens,

There’s sacking, canvass, osnaburgs and jean,

There’s ticking, broad cloths, cassimere and checks,

There’s velvets, bombasines and bombasets,

There’s many other fabrics coarse and fine,

Whose names prosaic will not rhyme,

And some few more which metre very well,

I could pronounce them but I cannot spell. [11]

The area’s economic situation still required long hours for the weaver; he might keep his loom operating twelve or fourteen hours a day. The Lyon children cleaned the loom-steads, mended harness bridles, washed brushes, or crouched behind the loom to return the shuttles. In the late 1830s, wages were still depressed—only three to five shillings a week for a weaver, fortunately, Lyon supplemented this meagre payment with irregular earnings from newsgathering and writing. He enjoyed both jobs; weaving gave him a chance to relate to his children, to talk to them, and teach them. It also allowed him opportunity to think and speculate on life, politics, and religion.

It was customary for Lyon and his family to engage in some other activity during a weaving session. They recited poetry, discussed politics, and argued religion. Frequently, one of the family read a chapter from the New Testament. Parents and children discussed individual verses. “For the most part, the average handloom weaver was intensely religious” (McLeod 16). Lyon and his family were no exception. His newspaper assignments had brought him in contact with many fervent believers, and he began the practice of morning and evening family worship. For a few short minutes all gathered, sang a song, read a scriptural passage, and prayed. Yet the family likely did not actively involve itself with any of the churches in town. An article in The Juvenile Instructor, published in Salt Lake City, Utah, indicates that Lyon joined the “Baptists and became a preacher of that church” (1902, 772). Several other articles written in Utah in the 1890s indicate some involvement by Lyon with the Baptist religion. The Baptist church was established in Kilmarnock in 1832, but no contemporary record of that church nor of the Lyon family confirms their membership in it. However, the mention of the Baptists does indicate a known truth: the Lyons were concerned about organized religion and actively sought participation. Several Sabbath Schools functioned in Kilmarnock; however, neither John’s nor Janet’s name appears on their records. The Lyon children were not baptized or christened in any of the organized churches—the Establishment, the Relief, the Reformed Presbytery, etc.

Despite a few other Protestant faiths and a smaller number of Catholics, the Presbyterian church (and its various offshoots) was the dominant church in Kilmarnock. It practiced a monthly fast day and prohibited the faithful from bathing, swimming, watering a garden, riding, or playing any sort of games on Sunday. Lyon found the church’s code too strict and limiting to his personal development and did not see fit to join. His newspaper work with the Witness and later the Western Watchman introduced him to alternatives to the established Church of Scotland.

The decades of 1830 and 1840 were filled with both political and religious turmoil in Scotland, and politics and religion often mixed. The political reforms of 1832 have already been mentioned. Not content with the scanty results from these reforms, and burdened by the serious economic depression of 1837–38, a group known as the Chartists demanded more rights, especially for the poor. John Lyon, as could be expected, was part of the struggle. Chartism, in May 1838, proposed equal electoral areas, universal suffrage, payment to members of Parliament (so poorer men could “afford” to serve), vote by ballot, and other reforms. During the same year, Thomas Chalmers, magnetic minister of the Church of Scotland, preached and pushed the nonintrusion principle, forcibly affirming that the government, especially in England, should not have power to continue “intruding” on the Church of Scotland by sitting in its assemblies and naming its ministers and thereby controlling or limiting its freedom. Finally, in a solemn assembly of the Church of Scotland on May 18, 1843, in one of the most dramatic scenes in Scottish religious history, Thomas Chalmers read his protest and in full ceremonial robes led 193 other ministers out of the meeting. Eventually, he was joined by 470 ministers who together formed the Free Church of Scotland. The grand exit with its resultant new church is known as the “Disruption.” Chalmers called for and organized a church free from political control and more involved with the needs and rights of the poor. Parishes were split into small working units where both paid and lay members could make visits to each others’ homes to determine needs and render assistance. Many of these ministers of the “Disruption” church made major sacrifices, giving up lucrative salaries formerly provided by the government. Lyon was deeply moved by this willing sacrifice, similar to the fervor he had witnessed in earlier splinter groups, the Cameronians and the Covenanters. In 1842, he offered his journalistic services to the Western Watchman. He had already been working for the Witness since 1840. In 1843, the Witness was the largest paper published in Edinburgh with a circulation exceeding 3,500; its pages also reached most of the major towns of Scotland. Lyon knew the editor, Hugh Miller, and Miller’s friend William Anderson, who edited the Western Watchman.

I was appointed their collector and canvasser and newsgatherer, and in order to fulfill this duty, I had to travel everywhere in Scotland, to gather their debts, lift advertisements and become acquainted with the feelings of the public regarding their outgoing and correspond with the office in Ayr, as well as support the interest of the paper by anything in the shape of tales connected with religious parties, who had formerly been oppressed by Governments for their profession, whether of one sect or another. [12]

Lyon was now truly a national traveler, journeying throughout Scotland. The Watchman was short-lived (1842–44), but Lyon’s work for the Witness continued until 1845 or 1846. Such was the fervor these two semireligious periodicals generated in Ayrshire that the editors of the Watchman and the Tory Ayr Observer at one time even contemplated a duel. [13] Lyon enjoyed the stimulation of tension and reveled in the reforming, revivalist atmosphere of the 1840s.

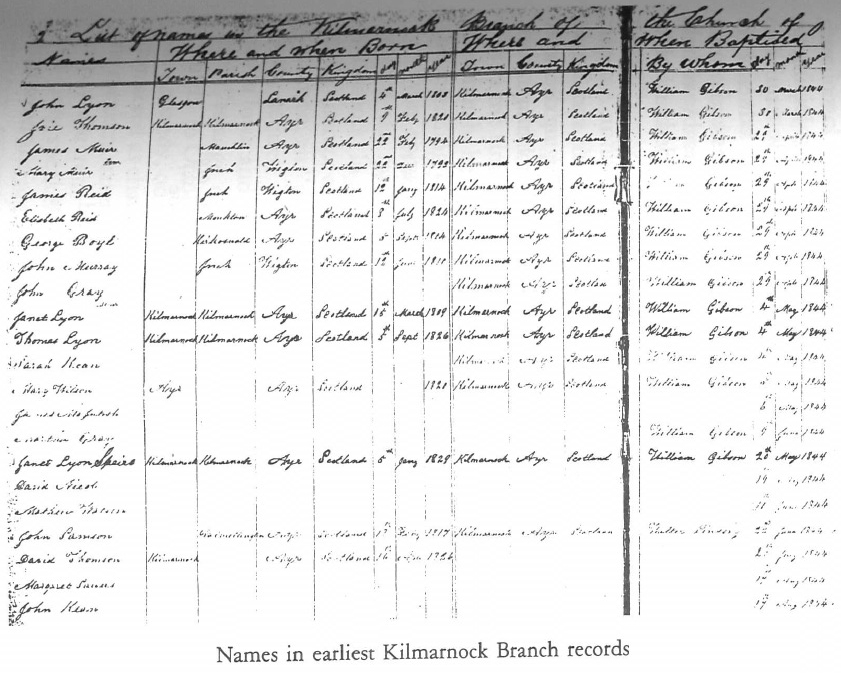

In 1837, a small group of proselyting missionaries from The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (Mormons) arrived in Liverpool, England. Their American origins were obvious by their accents; their religion was even more unique. They journeyed to Preston, England, where they preached and later baptized their first converts in Great Britain. Early in 1840, two former Scotsmen, who had converted to Mormonism and were then residing in North America, proceeded to Scotland and began proselyting work in Edinburgh and Banff. They were joined in May by Orson Pratt, an Apostle of the Church assigned to oversee missionary work in Scotland. Elder Pratt organized the first “branch” (congregation) in Paisley, near Glasgow. More missionaries arrived from the United States; as new converts to Mormonism demonstrated commitment, they too were called to go to other parts of Great Britain to spread the “good news” of a restored gospel of Jesus Christ. By 1851, faithful Mormons in Scotland numbered 3,291; seventy branches were organized. The rapid numerical growth was not without opposition from ministers and members of the dominant churches. The founder and recognized prophet of the Mormon church, Joseph Smith, was burned in effigy in Clackmannan in 1842; ministers of nearly all religions preached against the incipient Church. It fought back and prospered.

William Gibson, born in Paisley in 1809 and baptized into the LDS church in 1840, hearkened to a church call and became a zealous part-time preacher/

The first night I preached in Klmk Bro McDougall had taken a large hall and I had a large audience and I preached on the Apostasy of the Church and the necessity of Authority being given to men to administer in the ordinances of the Church. At the close of my remarks, as I had not spoken of Joseph Smith a man arose and asked “Pray, what Church do you belong to?” I said, “I am an Elder of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints.” “I thought so,” he said. Another man asked, “what proof can you give us that you have any more authority from God than any other Church or any other minister?” I replied, “the best of all proof and that which no other minister of any other Church dare give you without being found an imposter. . . .” Another man belonging to the Christian Disciples [Disciples of Christ] or Cambelites got up and gave me a challenge to a public discussion. “Very well my friend,” I said, “but before accepting your challenge I would like to know what Church you belong to.” He would not give me an answer, when John Lyon, . . . whom I did not then know, arose and said to me, “I will tell you my friend, he belongs to the Christian Disciples.” “Then my friend,” I said, “I will accept your challenge, the subject of the discussion to be the necessity of New Revelation, so you can appoint your committee; I will appoint mine.”

. . . I took a hall in Kilmarnock and preached in it through the day on Sabbath as well as in the Evening. Kilmarnock was a large place, full of Churches, Parsons, Religions and bigotry and although I had generally good meetings . . . the fear of man was so great that it was some months before I baptized any [of the residents]. [14]

Whether Lyon was at the meeting as a reporter, either because of the pre-publicity or due to a sincere yearning to find out about the new sect in town, is not clear. He obviously knew many people in attendance; he was able to identify the challenger as a Campbellite. Gibson’s diary records that Kilmarnock was a religious town; but for Gibson, a zealous, proselytizing Mormon, it was also bigoted. Actually, Kilmarnock was no different from other Scottish towns; for to staunch Presbyterians the Mormon faith was a radical departure from traditional religion and appeared to be even non-Christian in some of its doctrines. Still, that Gibson was always allowed to preach and that large numbers came to hear and debate him indicates openness and interest in religion in Kilmarnock.

Lyon and Gibson soon became friends; Gibson returned and preached nearly every weekend; Lyon attended, often playing the role of antagonist. Gibson left copies of the Book of Mormon for those investigating the new church; Lyon read the book and as many religious tracts as possible. After nearly six months of study, debate, doubt, prayer, and finally, spiritual confirmation, Lyon was baptized into the Mormon faith on Saturday, March 30, 1844. Gibson tersely records, “This evening I baptized the first two [people in Kilmarnock], John Lyon and Ivy Thomson.” [15] The baptisms probably took place in a secluded spot on the Irvine River near Paxton’s brewery, just a short distance from Lyon’s house on East Netherton Street, where a small dam made the water deep enough to immerse the new converts. Lyon enjoyed the honor of being the first Mormon baptized in Kilmarnock. His wife, Janet, had listened to him read from the Book of Mormon and had joined in the discussions regarding the new religion but had just given birth to her ninth child three days earlier and was still in confinement. Five weeks later, on Saturday, May 4, she and their seventeen-year-old son, Thomas, were baptized by Gibson; the other children over the age of twelve also received baptism as they matured and felt a conviction of faith.

Lyon’s decision to join a church and commit himself fully was extremely difficult for a man who had not previously been an active participant of any faith. He realized that union with the Mormon church would likely bring reproach and ridicule from friends and neighbors. It might also mean loss of work, both contracted weaving and newspaper writing. Joining the Mormon church, at age forty-one, would surely require his adopting a new set of habits, activities, and values. How would Janet’s parents react? What about uncles and cousins in East Kilbride and Blantyre? Would Lyon be able to hold the family together in a new faith that demanded such strict allegiance? He was aware that many Mormons were leaving Scotland and emigrating to the “promised land” in America; would he too feel the need to “gather to Zion” and forsake the land of his fathers? Lyon truly faced life-changing decisions. Thirty years later, however, from a different vantage point he recalled:

How sweet the Gospel message came,

When first I learn’d its light and pow’r;

‘Twas all an anxious heart could claim,

It and the Scriptures were the same:

I was a “Mormon” from that hour!

But there were other truths to learn,

Which then I could not well discern.

How strange it seemed—the Elders’ cry:

“Fly, fly from BabTon’s coming woe”:

. . . .

Why should I leave my native land,

I thought, and all love’s labor cease

. . . .

Here I can worship God and dwell

Where all my grandsires lived of yore.

(Songs of a Pioneer 81, 82)

In May of 1844, the headquarters of the LDS church in Liverpool asked William Gibson to move his family to Kilmarnock and direct the missionary work there. He immediately left Paisley and settled his family in a two-room house, one room of which he used for his wood-turning business. As branch president [parish leader] and elder of the LDS church in Kilmarnock, he continued to preach, debate, and baptize. By the end of 1844, there were twenty-four Mormons in Kilmarnock; the Church grew rapidly as a result of eager preaching and proselyting by Gibson and Lyon. On June 20, 1844, Gibson and Peter McCue (presiding LDS authority from Glasgow) ordained Lyon an elder in the Church, bestowing full authority to preach and baptize in Aryshire. [16] Just seven days after this ordination, the founding prophet of Mormonism, Joseph Smith, was assassinated in Illinois. Nearly two months later, when Lyon learned that the death occurred just at the time he had received the priesthood authority of the Church, he felt a providential mission to somehow further the spreading of the restored gospel.

Lyon enjoyed the respect of many; Gibson and Lyon teamed up for several public lectures and discussions in Kilmarnock. In July, they debated the Reverend James Morison on the concept of baptism and salvation. In August, Alexander Robertson, an “apostate” Mormon from Paisley, came to town at the request of local ministers; he was given the largest hall in town and preached strongly against the Mormons and their “strange doctrines”; Lyon and Gibson defended the Church. In October, Gibson debated a Methodist preacher, a Mr. Kennedy, on the topic of baptism by complete immersion. Lyon acted as chairman of these public meetings, introducing the speakers, attempting to keep order, and collecting monies to pay the rent for the hall. Lyon was a feisty organizer and fiery speaker; on several occasions he got into ardent discussion and argument. One of Kilmarnock’s better-known citizens, expressing respect for Lyon’s ideas, observed that

John had clear views of progressive perfection, and declared that the summit could only be reached by perpetual culture, and that those who left the world in a state of mental doltism would be set on a very low stool in the next. John believed in class spiritual as well as class temporal. While talking to me one day of the reign of bliss, “Depend on it,” said he, “society will be very select there. There will be no imitations; worth alone will procure a seat suited to the mental capacity. Would it be fair to seat such minds as Sir Isaac Newton’s on a barrow tram to listen to an Irish nawie rehearsing what masses of dirt he had set in motion by brute force? Not likely. (Hunter 6)

Lyon’s friend, Gibson, did not fare well with the solid citizens of Kilmarnock. As a newcomer, he never truly fit in and viewed any opposition to his preaching as the work of plotting enemies. He was never able to contract sufficient wood-finishing work to live comfortably:

The good Christians of Kilmarnock now tried a new plan to get rid of me and that was to starve me out. [They] laid their heads together and would not purchase any of my work. And the Saints [Mormons] although willing to assist were too poor and trade was very dull. . . . So I had to leave in search of employment. (Gibson 52)

Economic duress forced Gibson to move to Glasgow in February 1845, and the Church then named John Lyon as presiding elder of the rapidly growing Mormon congregation. He became a preaching-traveling minister. Religion, not news-papering or weaving, now became his first craft. He voluntarily gave up working for the Witness, and the Western Watchman ceased publication in 1844, so he had no religious conflict to resolve with that paper. He continued to gather news and subscriptions for the Kilmarnock Herald and the Ayrshire Agriculturist and solicit contributions for the Ayrshire Wreath, an annual of local poetry. The family weaving returned sufficient money to subsist; Lyon received no salary from his church but still dedicated most of his time to traveling and preaching its doctrines. He turned his poetic energies and inspiration away from local themes and submitted his writings to the LDS church’s Millennial Star, published in Liverpool. From 1844 until his departure to England in 1849, he penned fifteen poems for the Millennial Star.

Lyon’s first’ ‘Mormon” poem, entitled simply “Man,” was written in July of 1845 and published in the Millennial Star on November 15 of the same year. The thirty-line poem is a philosophical comparison of man’s life to the elements of nature:

Man, when his constitution is unfurl’d

Resembles much this great material world!

Of dust and earth his sluggish flesh is made;

Like rocks his bones, in strength and firmness laid;

How like the seasons to his growth and fall,

How like the frost and snow to death’s white pall. (176)

As a poet formed during the years of Romantic intensity, Lyon explored the relationship of life to the natural world. His second Mormon poem, written on February 5, 1846 (Millennial Star, March 1, 1846), is an admonition to the Saints scattered through Iowa. Titled “Exodus,” it shows a remarkable early knowledge of where the outcast Mormons were to settle:

Go seek some lonely valley . . .

Up and away, to your Mountain home,

Where wild beasts prowl, and red men roam . . .

Go where ne’er a white man trod:

Unveil each Indian nation,

Unfold the stick of Ephraim’s God. (80)

All the poems reflect an optimistic view of life, and many point to a future millennial reign on earth. Lyon sensed the Mormon mood of the day, feeling that he was part of a new order that would soon usher in the Second Coming. His poems reflect the themes he and Gibson preached—an evil world, gathering to Zion, the artificiality of appearances, and love as a conquering force. He also wrote poems to celebrate specific occasions and people—the departure from Great Britain of Samuel W. and Franklin D. Richards for “the Camp of Israel” in America (February 15, 1848); he memorialized James Young, a missionary who died in Scotland in 1847. He penned verse for two lonely sisters in a rural area of Scotland who felt isolated from the Church, admonishing them to firmer faith and to someday leave “Babylon” and gather to Zion. Most of these early poems were later collected and published in his Harp of Zion in 1853.

During the decade of the 1840s, five more children came to the Lyon house. Matthew was born in 1842, Mary in 1844, Margaret in 1846, Agnes in 1847 or 1848, and Franklin D. Richards, child number twelve, in 1848. [17] The name of the last child is further indication of John’s and Janet’s commitment to Mormonism—he was named for one of the early leaders of the Church who carried out successful missionary work in Great Britain. All the other Lyon children had received simple and traditional family names; Franklin was blessed with three given names. John was forty-five and Janet thirty-nine when Franklin was born; the family was now complete. The Lyons had been fortunate in that all of their older children had survived the dangerous years of infancy as well as the cholera epidemic of 1832. However, in January of 1848, thirteen-month-old Margaret (child number ten) died of an unmentioned illness; in March of the same year Agnes died, living only sixteen days; Franklin also died in Kilmarnock, at age three, in March, 1852—none of the last three Lyon children survived childhood. Janet’s health was obviously at a low point, having given birth to twelve children in twenty-two years.

While the Lyon family was growing in numbers, it was also growing in another direction. As the parents and older children expanded their family weaving business, new and finer looms were acquired. Lyon recalled “being the proprietor of a six loom shop, occupied by my own children and apprentices. . . . I was an Agent for three manufacturing houses in Glasgow and Paisley to give out webs for them.” [18] By 1846, Lyon had become a fine businessman. One of his apprentice weavers was a young LDS convert, George Spiers. According to Lyon family tradition, Spiers moved into the already-crowded household, fell in love with young Janet (nineteen years old), and married her. However, at the time of their marriage, on November 24, 1848, parish records show that he was living on Tilchfield Street. In spite of their membership in the LDS church, the Lyons still posted banns, and the marriage was performed and recorded in the Kilmarnock Parish Register. Thomas, the oldest child, also courted a local Mormon girl, Mary Ann Higgins (living on Low Church Lane), and married her on January 4, 1849, just six weeks after his younger sister’s marriage. [19]

As the local ecclesiastical leader, Lyon directed the growth of the Kilmarnock Branch. He performed the funeral service for John Kean in 1846. He blessed (christened) most of the babies born to LDS families in Kilmarnock. But his biggest joy came in baptizing new converts, most of whom drew near to the Church as a result of his preaching. On November 11, 1844, he baptized Ann Watson; in 1845, he baptized eight more new Saints in Kilmarnock alone, two in 1846, three in 1847, and twenty-two in the rapid-growth year of 1848. However, he did not baptize his own children even though he had the authority to do so; custom dictated that a friend should. Lyon also pronounced blessings on the new Church members and imparted to them “the gift of the Holy Ghost.” He visited the sick, giving them health blessings. The Scottish press viewed this activity with critical incredulity, poking fun at the simple-mindedness of the Mormons. The Kilmarnock Journal reported, in a very biased fashion, a local incident: