To “Our Ain Mountain Hame” (1853)

T. Edgar Lyon Jr., John Lyon: The Life of a Pioneer Poet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989) 155–212.

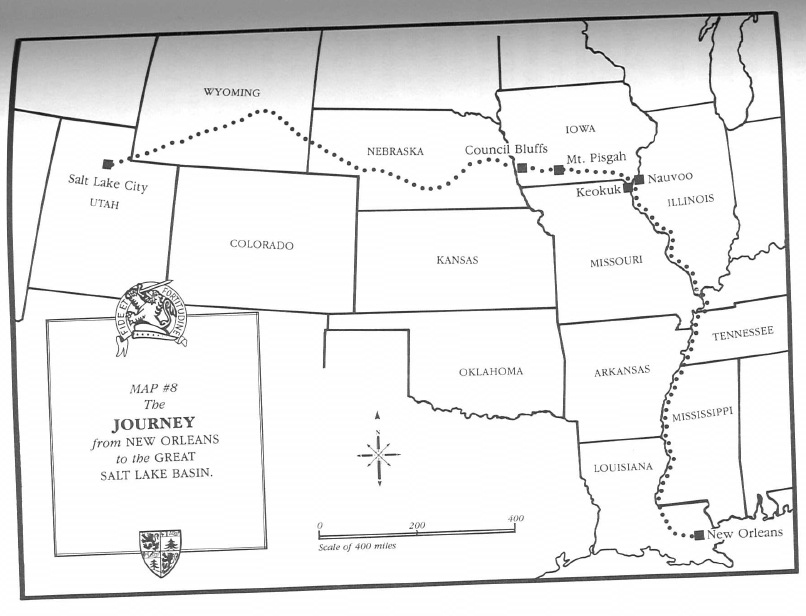

The year in which John Lyon celebrated his fiftieth birthday was undoubtedly the most momentous of his life. Publishing his poetry in book form, bidding farewell to Scotland forever, sailing over 5,000 miles of ocean, steaming 1,400 miles upriver, trudging another 1,400 miles on foot across plains and mountains, and eventually establishing his family in a desert valley 8,000 miles from “name’—all suggest 1853 as the pivotal year in Lyon’s life.

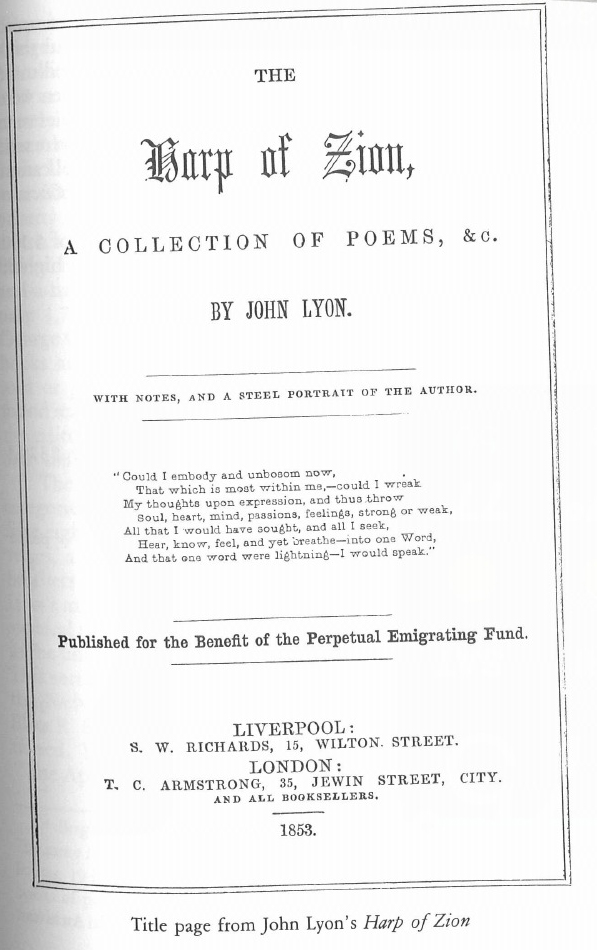

For a man who did not master reading and writing skills until in his mid-twenties, the publication of a handsome volume of his poetry was pure literary ecstasy. As early as October of 1851, Lyon had decided he would publish his poems in a single volume and received permission from Franklin D. Richards to do so. In September of 1852 Lyon delivered the 104 manuscript poems to Samuel W. Richards, the new mission president. [1] Franklin D. Richards had seen the possibility of profit for the Perpetual Emigrating Fund from the sale of a finely bound volume and commissioned local printer T. C. Armstrong to publish the poetry.

It was late in the afternoon [of early January, 1853] when J. Sadler of 16 Moorfields, Liverpool, loosed the screw of the old book-press and, with pride well deserved by a good bookbinder, handed a beautiful book to John Lyon, the author. . . . It was well stitched, fine cloth covered boards, elegantly decorated with designs in gold. It contained two hundred twenty-three pages of fine paper, well trimmed and gilt edged. The author’s picture was prominently displayed on the page opposite the frontispiece. [2]

When Orson Pratt first suggested the idea of a collection of LDS poetry to Lyon, President Pratt intended that it be a high-quality publication; his successor, Franklin D. Richards also urged a first-class book. Accordingly, three editions of the book were printed, each having a separate cover: (a) the standard cloth embossed (selling for two shillings, six pence), (b) cloth extra, with gilt edges (for three shillings, six pence), and (c) the luxury edition in morocco gilt extra, including fifty copies on superior paper (for six shillings, six pence—approximately one dollar and 65 cents in U.S. currency at that time). Considering that the average factory worker or weaver in 1853 made less than one shilling per day (about 25 U.S. cents), the book was quite expensive. But a consolation to the now-poorer purchaser came from his knowledge that not only was he getting a fine book but he was also contributing to the worthy Perpetual Emigrating Fund. One humble LDS traveler, James Brady, a PEF immigrant, records: “When I left Glasgow [in 1853] I had 5 shillings [to my name] and I gave 3 and six-pense in Liverpool for the harp of zion” (Buchanan, letters). That a near-destitute man would have spent more than half of his meager savings to purchase a volume of poetry is almost beyond present-day imagination.

On January 29, 1853, the Millennial Star announced that “the Harp of Zion, a collection of poetry by Elder John Lyon, has been nobly donated to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund by its talented author, to help on the praiseworthy and God-like object of gathering the Lord’s poor to Zion” and that it was now ready for sale at the Millennial Star office. Although the words nobly donated, talented, praiseworthy and God-like were used to encourage purchase, the Church leaders in Liverpool were justifiably proud of the edition, which was “got up in a superior manner, printed in new type, on beautiful thick paper, and splendidly bound. No Saint will be satisfied to be destitute of a copy” (Millennial Star 1853, 73). Members were urged to buy additional copies for gifts to friends. Copies were distributed to bookstores throughout Liverpool; some were sent to booksellers in London and other major towns. Publication details appeared in the important London Publishers’ Circular (vol. 14, 1853); Lyon’s book was officially launched.

Samuel W. Richards had ordered the printing of 5,100 copies; the actual count after binding was somewhat higher:

| Cloth | 3,881 |

| cloth extra (gilt) | 917 |

| morocco gilt | 300 |

| superior edition | 50 |

| 5,148 |

Total expenses for the production were nearly £379- [3] Richards was taking an obvious gamble by ordering such a large number but in characteristic Mormon fashion was “thinking big.” If all books were to sell at suggested prices, £607 would accrue to the PEF, a net profit of £228, approximately $1150 U.S. currency (Liverpool Financial Records, November 16–17, 1853), enough to assist a score of people to Utah. Unfortunately, sales to the financially strapped Saints were not as high as expected; food and shelter had to take priority over poetry. Members were already contributing to tract funds, the PEF, the Danish Mission, the Traveling Elders’ Fund, the Salt Lake Temple Fund, etc. Even so, a year-and-a-half later, 979 copies had sold. By 1861 sales had slowed; only 1,765 were paid for by that year. Mission President George Q. Cannon lamented the backlog, crated most of the books and sent them to Utah, where they eventually were sold or given to friends. [4] “Thousands of copies are to be found scattered through the homes of Utah,” warmly observed the editor of the Millennial Star on Lyon’s death (Millennial Star 1889, 813).

The 104 pieces in the volume are divided into four major categories: Poems, Sonnets, Songs, and Hymns. The poems, fifty-eight in number, include an assorted collection of early verses, a number of words written in praise of the Richards brothers and other Church friends (especially people from Lyon’s missionary days in Worchester), and many short philosophical pieces dealing with LDS doctrine and Lyon’s exultation in the unique, all-encompassing gospel of the Mormon church. This section also includes a poem written to Lyon by one of the Twelve Apostles, John Taylor, as well as a poem written by Eliza R. Snow to Franklin D. Richards in which Lyon is mentioned. The poems include “Forgiveness,” “The Prophet,” “The Apostate,” “Presidency,” and “A Marvellous Work and a Wonder”; one is “Inscribed to His Excellency Brigham Young, Governor of Utah Territory” Many of the works praise Church friends or are dedicated to British Church leaders. [5]

The second section consists of eighteen tightly structured sonnets. Most are of a more timeless, universal nature than the “poetry of occasion” in the first section: “Faith,” “Lust,” “Regret,” “Obedience,” etc., are all religiously based sonnets.

The third section comprises sixteen songs which were to be sung to popular Scottish tunes: “The Old House at Home,” “The Ivy Green,” and “The Lass o’ Glenshee.” Most of the songs reflect LDS goals or activities: “Song of Zion,” “Mountain Dell,” “Mormon Triumph.” A few are light, almost jocose in nature.

Ten hymns make up the final section of the book. Seven of these hymns were already in print in the 1851 LDS hymnal published in Liverpool. Lyon’s young Apostle friend, Franklin D. Richards, had put the new hymnal (ninth edition) together in an attempt to replace “about sixty hymns with more appropriate ones.” [6] The new anthems were mainly from the pen of Mormon poets; Lyon was the Mormon poet most frequently represented in the volume. Like previous editions, the 1851 Sacred Hymns and Spiritual Songs had the appearance of a tiny book of poetry since it contained only the words for the church songs with no musical notations for its 296 hymns. Lyon’s poem/

| 1851 Hymnal | Page | Harp of Zion | Page |

| O Lord, Responsive to Thy Call | 60 | Confidence in the Lord | 24 |

| O Lord, Do Thou Thy Gifts Bestow | 90 | Confirmation | 202 |

| When Sickness Clouds the Soul with Grief | 96 | Anointing and Prayer for the Sick | 203 |

| O Lord, Do Thou in Heaven Seal | 129 | Marriage | 204 |

| To Thee, O God, We Do Approach | 121 | Praise to God | 206 |

| Come, Let us Purpose with One Heart | 123 | Practical Religion | 211 |

| Hail! Bright Millennial Day of Rest | 74 | Millennial Hymn | 213 |

Three more songs, “True Religion,” “Christ’s Second Coming,” and “Anthem,” complete Lyon’s hymns. As with many of the poems in Harp of Zion, most of the hymns deal with a specific event or ordinance and were likely sung on such occasions (marriage, blessing the sick, confirmation after baptism, etc.). Most of these hymns remained in future editions of LDS hymnals until 1927; two survived until 1948, keeping Lyon’s name before the LDS membership each time they opened their hymnbooks.

Lyon was justifiably proud of his volume of poetry “got up in superior manner.” The six shilling, six pence edition—with its embossed gilt inlays on a green cover—is now a luxury collector’s item. The Harp of Zion signified a new venture for the LDS church: authorities had previously printed newspapers, tracts, magazines, standard scriptures, and an emigrant’s guide—practical matters for a pragmatic church. Now, however, the Church sponsored and sold a book of creative poetry, its first major venture into aesthetic matters. The tacit approval thus granted by the Church indicated that many authorities as well as lay members felt that the uniqueness of the Restoration must be captured in creative form as well as rhetorical and scriptural discourse. During his later life, Lyon basked in warm acclaim as the author of the first volume of poems ever issued by a member of the LDS church. All Church magazines and newspapers of the nineteenth century acknowledged this as a first. The claim, however, is subject to some dispute, since in 1840 Parley P. Pratt had published a 140-page collection of poems and miscellaneous writings. It did not, however, have the certification of the Church implied in Lyon’s 1853 work, nor was it widely read. Pratt’s work faded, whereas Lyon’s was kept alive by the many hymns he composed and by his visibility in Church councils in Utah for thirty-five years after the book’s publication.

Franklin D. Richards, Brigham Young, John Taylor, Orson Pratt, Orson Hyde, and other Church leaders in Utah received free copies of the volume. Upon receipt of her finely bound copy in 1853, the dynamic Eliza R. Snow inscribed a few lines to Lyon:

Like a bright golden gem, in a casket refin’d,

Is the “Harp” you presented to me:

I admire its bold speech, and its high tone of mind,

And its accents of innocent glee.

I accept the fair gift, the rich, beautiful boon,

With gratitude mingled with pleasure:

With its heaven-inspir’d pages I love to commune,

And, possessing it, feel I’ve a treasure.

(Snow 235)

In late 1852, Lyon had received £11 from the Liverpool office to travel to London to sit for a portrait. He went to Frederick Hawkins Piercy, a convert to the LDS church who in 1853 would also journey to Great Salt Lake City. Piercy was just twenty-two at the time but had already achieved a degree of success by exhibiting at the Royal Academy of Arts in London (Piercy xii). Piercy completed a sketch of Lyon that was included on the first page of the Harp of Zion. Lyon appears as if floating, in an oval frame, his long hair over his ears, proud, noble, with pursed lips, a long straight nose, and penetrating eyes. A high white collar sticks above a formal coat and black handkerchief. Lyon was forty-nine at the time but appears a much younger man. The sketch portrays a traditional Romantic poet, caught in a fleeting moment as he stares at the reader of his verse. Once again, this visual representation of the author with the text was a first in LDS publishing and provided Lyon with instant recognition among thousands of the Mormons he would later meet (see frontispiece).

Despite the delight at seeing himself in print, Lyon did not have time to rest on his publication. He and Janet had received permission to emigrate to Utah’s Zion and so began the months of preparation, sorting, abandoning, making new clothes, gathering funds, finishing up Church business in Glasgow, and deciding what would stay in Scotland and what would travel the thousands of miles to the mountains. The first major question—what clothes to take on an 8,000 mile, seven-month journey—was partially resolved by the family weaving business; parents and children simply wove their own. Lyon recorded in his personal notebook each item packed for America and the chest in which the item was located.

Chest No. 1

John Lyon, Sen.

4 pair of trousers

5 vests

2 plaids [mantle, cloak]

4 coats

neckershifts [neckerchief]

2 gravats [cravat, scarf]

4 pairs of stockings

5 semmets [undershirt]

4 pair of drawers

John’s Clothing (John, Jr., age 18]

4 pair of trousers

4 vests

2 neckershifts

4 coats

2 pair of stockings

1 jacket

Matthew’s Clothing [age 10]

2 coats and one jacket

3 pair of trousers

3 vests

2 gravats

1 paper of pins

1 paper of tapes

1 paper of thread

Chest No. 4

Ann’s Clothing [age 21]

7 shifts [undergarment, chemise]

3 trousers

5 frocks

5 short gowns 3 cloaks

1 plaid

2 polkas [woman’s jacket]

3 coats

1 gravat

Lillie’s Clothing [age 16]

3 shifts

3 pair trousers

2 polkas

2 coats

5 frocks

2 cloaks

Chest No. 5

Mrs. Lyon

6 shifts

3 trousers 6 gowns

3 coats

3 pair of stockings

4 shawls and plaid

1 boa [long, fluffy scarf]

2 neck napkins

5 mutches [white night cap]

2 screens [head scarf, shawl]

1 knitted polka

5 silk shawls and plaid

2 neck ties

1 shimizet [chemise] 1 pair cuffs

Mary Lyon [age 8]

6 shifts

3 pair trousers

1 polka

1 muff

4 petticoats

1 white gown and petticoat

2 frocks

2 cloaks

3 pair of stockings

The previous lists indicate that the Lyon family had means with which to make or buy many things; it is not the clothing of the extremely poor; many luxury items were part of the large chests. Lyon and his two sons shared a trunk; the four females shared two. The same notebook [7] indicates that on January 5 Lyon purchased cloth valued at £1.18, likely to make some of the previously mentioned clothes. Later in the month, Lyon had his watch mended and bought boots, shirts, a brush, a comb, a knife, stamps, and paper, necessary items for the trek to the mountains. The contents of chests two and three are not listed in the notebook, but they assuredly contained boots, weaving tools, a turning lathe, a wood plane, a saw, leather goods, and personal necessities.

The Lyons disposed of tables, chairs, a loom, some cooking utensils, eating ware, and a few extra clothes that they could not take with them; the sale of such items raised a few pounds for the journey. The family was to form part of a Ten Pound Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company. The price of £10 was the approximate amount for each adult for the journey, as suggested by Brigham Young and his travel agents in England, New Orleans, and Keokuk, Iowa. Children under fourteen were required to pay half this amount. The Perpetual Emigrating Fund would pay any additional amounts needed to get the Saints to Utah. Expected profits from the Harp of Zion were likely viewed as total payment for Lyon and his family; he never appeared on later PEF debtor lists. The couple’s two oldest children, Thomas and Janet (Spiers), were married and would have to earn their own way to the valley later. Five of John and Janet’s children had died during the previous five years; the five remaining children, ages eight through twenty-one, would accompany their parents. So John and Janet had to raise £50 for themselves and their three older children and £5 each for Mary and Matthew—a total of £60 (approximately $300 in U.S. currency of the time). Some of this amount came from the sale of furniture; most came from contributions from Church members in the Glasgow Conference. As conference president, Lyon collected and carefully recorded donations from conference members to the Salt Lake Temple Fund, to purchase the Millennial Star, to aid the Danish Mission, to the Traveling Elders’ Fund, and so on. A few of the Saints, less strapped by poverty than most of the lower middle-class converts, were able to donate a few shillings directly to the Lyon family cause. During January and February, Lyon records the names of more than 550 people, each of whom made a small contribution—a few pence, a few shillings—to various funds. He notes some of these as “Subscriptions for J. Lyon, with names of donators.” His own son-in-law, George Spiers, is among the contributors in Kilmarnock, as is a “Mrs. Eccles.” After a long list from the Second Calton Branch, the entry notes that John Kinlock contributed two shillings “and his 2 children—3 pence.” John Roberts is noted as promising to donate “a pair of boots or shoes.” A single name, David Drummond, rates a special page; from December 29, 1852, through February 14, 1853, he contributed £22 to the Church, much of which was intended for the Lyon family. A roughly scribbled note in pencil (monies received were noted in pen) gratefully states: “David Drummond will have his Endowments and blessings for the dead and the sealing ordinance; if the Lord spares my life.” John felt an unpayable debt of gratitude for the charity of this man and promised to hastily complete the saving ordinances for him as soon as a facility was available in Great Salt Lake City.

After John Lyon’s four years of full-time service to the Church and after the Lyon’s official permission to “gather to Zion,” the emigration of the Lyon family became a cooperative effort. Church members recognized the spiritual contributions and personal sacrifices that the Lyon family had made and willingly gave as much as they could. As with many others, the departure of the Lyon family became a conference project. The faithful who shared their meager funds knew that one day they too might be blessed to “leave Babylon” and go to the Salt Lake Valley. Lyon’s written record of the generosity of the members of the Glasgow Conference is a testimony of the willingness of many poor Saints to participate in a venture larger than themselves. From Lyon’s personal diary and from Church records, it is evident that Lyon baptized at least 715 people in Great Britain; many of them, especially those in Worchester and Glasgow, contributed to the Lyon family emigration fund.

Leaving Scotland, Lyon’s home for fifty years, was both painful and joyous for him and his family. His parents were dead, and he had no living brothers or sisters; he visited his uncles in East Kilbride, bidding them goodbye and at the same time inviting them to unite with the LDS church. Janet still enjoyed association with many of her family members in Kilmarnock and tried to make them understand her spiritual need to gather to Utah. In these moments of deep feeling, Lyon drafted many yearning poems. One poem, celebrating his departure, appeared as the final selection in the Harp of Zion:

THE POET’S FAREWELL

Fareweel, my cattie,

fareweel Fareweel, my countrymen a’;

To auld Scotia’s land;

And her glory is faded awa;

For the terror of night

Gives the tyrant his right,

And her sons starve with nothing to do.

Proud Scotia, for ever, adieu.

The unpublished “Song Written Extempore at the Falls of Clyde in 1852” expresses Lyon’s love for the Scottish landscape, his pride in his country’s history, but his need to depart:

Fareweel my native vales and hills

Where youthfu’ scenes my mem’ry fills

Where Mouse swell’d by a hundred rills

Runs murm’ring to the Clyde, o.

Where nature smiles so cheery

I’ve wand’red wi’ my deary

Nor never thought it dreary

When walking by her side, o.

Far doon thy heather-clad fairy dells,

Where Wallace hid frae south’rn swells,

I’ve pulled fair Scotia’s heather bells,

Among thy banks so briery.

In distant lands and fairer climes

Where freedom reigns and truth combines

I’ll seek a home where tyrants’ crimes

Nor pourtith, e’er will come, o.

Where nature smiles so cheery

I’ll wander wi’ my deary

Where age nor toil can’t weary

In Zion’s happy home, o.

Both poems lament the supposed rule of tyrants and the limitations on life in old Scotland; Lyon never chose to comment on the tyrants in America who martyred the first prophet of his church. Like most British Mormons of the day, he found much to criticize in Scotland and almost nothing but good in the unknown mountains of America.

The year 1853 was not only a pivotal date for Lyon; it was a high-water mark for the Mormon church in Great Britain as well. Its missionaries had baptized over 8,000 people each year in 1849, 1850, and 1851—the highest numbers ever recorded for the mission. The burst of new members in the country swelled emigration figures approximately four years later, a reasonable period for new converts to complete their business transactions, save money, and apply for and receive permission to emigrate. In 1852, a mere 581 Britons departed for America; in 1853, with the aid of the Perpetual Emigrating Fund and the large numbers of 1849–51 converts, 1,778 members left for the Utah Territory (Evans 245). Sonne lists 2,603 people departing from Liverpool in 1853; some of these were Scandinavian Saints who had transhipped through Liverpool (Sonne 150). The period 1853–56 represents “the greatest concentration of Mormon emigrants ever seen,” more than 11,000 in four years (Taylor 145). Internal affairs in Utah in 1857–58 reduced emigration to a few hundred each year; the 1853–56 peak was never again achieved. The seven members of the Lyon family formed a small part of the mass movement which began in 1853.

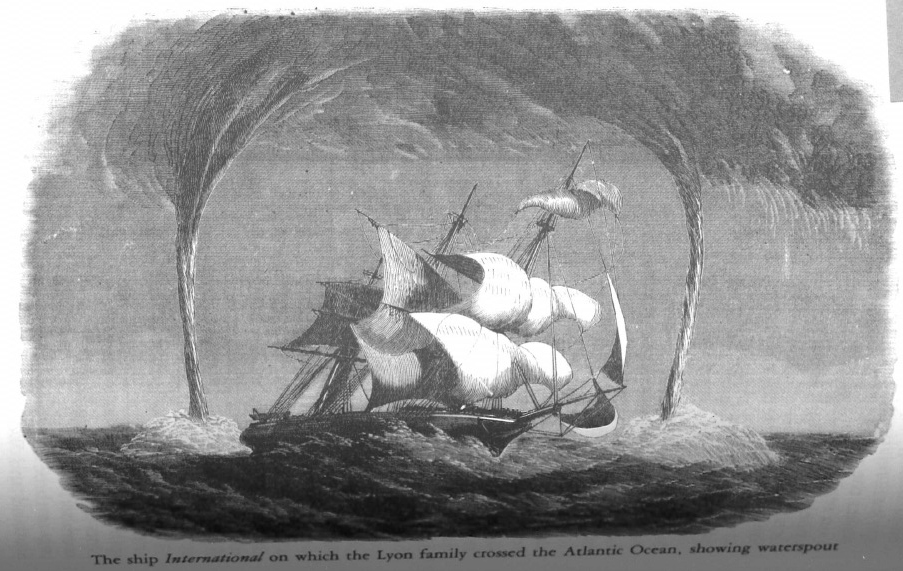

Lyon began a journal to record the voyage: “Saturday 19th February 1853. Left Glasgow for L-pool at eight o’clock p.m. per steam ship Princess Royal. In company with a few Saints bound for G.S.L. City.” [8] He described no emotion or regrets on leaving, an unaffected beginning for an 8,000 mile trek. The voyage by coastal steamship lasted twenty-four hours and cost £7 for the family. On his arrival in Liverpool, Lyon laconically noted: “Sunday 20th had a good passage and landed at 8 p.m.” Following established procedure, the Lyons boarded the ship International the next morning, sleeping on board for four nights, marking time while the company of 425 Saints assembled from all parts of England, Scotland, and Wales. The Church agent, Samuel W. Richards, had made special arrangements for passengers to board upon arrival in Liverpool to avoid “the ruinous expense of lodging ashore and preserve many an inexperienced person from being robbed by sharpers” (Piercy 50). The frugal Lyons appreciated the savings.

The International was a large sailing ship (1,003 tons) completed in 1851 in Kennebuck, Maine. It was constructed of live oak from Georgia and pine from Maine (Sonne 50, 150). The ship’s 1853 voyage from Liverpool to New Orleans was the first and only passage in which it carried LDS emigrants. The International boasted a crew of twenty-six and was commanded by amiable veteran Captain David Brown, who made his home in New Orleans. Passengers could enjoy the fresh air of the open deck but were berthed on lower decks. The few wealthy might travel with private bunks in Cabin Class. For a few shillings or a pound extra, some could travel in Second Cabin. “The great majority of the Saints, of course, were always in the steerage” (Taylor 180). Lyon’s family and indeed most PEF emigrants bunked in this lowest deck, with its dark, low ceiling, its long rows of box-type beds on each side and its eating table that extended down the center between the beds. By 1853, numerous British laws and, to a lesser degree, American laws had standardized food, space, sanitation, and cooking requirements for ships. At best, however, the accommodations were cramped, noisy, and smelly. Buckets located in steerage were emptied regularly into the “head,” a cranny that was located at the front or head of the ship and so was regularly rinsed out by wave action. Passengers slept four to a berth, with a 6’ x 18” space designated for each occupant. Rules of conduct included rising by 7:00 A.M., cleaning before and after meals, and airing bedding twice a week if weather allowed. Wash days occurred twice a week. No alcoholic drink or gunpowder was permitted on board (Taylor 180–83).

On Thursday, February 24, Samuel Richards brought the 425 Mormon passengers together. “Christopher A. Arthur was appointed president (of the LDS passengers) and Elders [John] Lyon and [Richard] Waddington to be his counselors” (Lyon Diary). Arthur, self-titled “the largest man of the Restoration,” standing six feet six inches and weighing 280 pounds, was a baker from Wales; Lyon, of course, hailed from Scotland, and Waddington from England—a true geographic representation of the ship’s population. Two days later, while the ship was still at anchor waiting for favorable winds and while in the midst of a snowstorm, these men divided the eighty-eight berths in steerage into six wards, with an additional two wards organized in the Second Cabin. They also appointed a president to watch over each ward, which consisted of approximately fifty people. There were 237 of the passengers who belonged to the Ten Pound Company; 188 were classed as “Ordinary,” which indicated that they were paying their entire fare to the valley. The ten-pounders contributed £10 only, and the Perpetual Emigrating Fund was to supply any additional monies needed to see them through to Great Salt Lake City (Piercy 43). Fare in steerage on the International was £5 for adults over fifteen years old and half of that for children ages three through fourteen; consequently, half of the amount paid by each adult ten-pounder went to ship fare. Much more would be needed to see them through to the mountains.

While waiting for all the passengers to arrive and then for favorable sailing winds, Lyon and his family mingled nervously with the other anxious passengers. Their religion gave them a sense of unity and cooperation not normally present among emigrants from such diverse backgrounds and areas. New friendships, coupled with the anticipation of embarking on a grand adventure, helped the passengers overcome the deep nostalgia over leaving their homeland. Christopher A. Arthur was the natural leader of the group, not only because of his size but also because he had brought nearly a hundred people with him from Abersychan and Monmouthshire and was paying the fare for forty of them. Among these was his non-LDS son, Christopher J., who later recalled that he “found a great friend in John Lyon and we were like father and son during our trip” (4). In Liverpool, Lyon and Christopher J. attended the theatre “for which I received a lecture from father, who was not a theatre-goer,” records the chastised son. Lyon’s more open, even liberal attitudes may have occasionally clashed with the more conservative senior Arthur, but in general the two got on very well. At the end of the journey, Christopher A. reported to Samuel W. Richards:

I rejoice to say that my right hand Counsellor, Elder John Lyon, is one of the best men I have ever met with, and I hope we shall be near neighbours when we reach the Valley of the Great Salt Lake. (Millennial Star 1853, 359)

Such love and goodwill bode well for the passengers, who would be cramped and crowded together for eight weeks.

The ship provided food and water for each passenger, but to vary the limited rations, many of the travelers purchased extra provisions: potatoes, ham, dried salt fish, onions, baking powders, lime juice, plums, and currants were advised (Piercy 56). By law, the ship had to provide three quarts of water a day to each adult, and, on a weekly basis,

2 ½ pounds bread or biscuit

1 pound wheaten flour

5 pounds oatmeal

2 pounds rice

½ pound sugar

2 ounces tea

2 ounces salt.

Apparently, LDS travelers received some additional sugar, three pounds of butter, two pounds of cheese, and one pint of vinegar (Piercy 55–56). Still, the diet became understandably monotonous and unpleasant to those used to more fruit and vegetables. Passengers had to furnish their own bedding as well as cooking and eating utensils; the ship provided the cooking apparatus and fuel.

Friday, February 25, a steamer tugged the big International out of Stanley Dock into the River Mersey, but for three days the ship lay at anchor awaiting favorable winds. During one of these doldrum days, Lyon noted that “a ship was seen on her beam ends, about a mile distant from leaward; several persons lost.” Obviously, such sights reminded the novice travelers that they too could be subject to storm and shipwreck. In their confined, dark quarters, they would hear strange creaking noises, hear the anguish of sick and crying children, hear the retching and vomiting of the seasick, hear the wind whistling through the rigging, and feel the waves crashing into the hull. Prayers for safety were frequent. However, in 318 crossings of the Atlantic between 1840 and 1890, no LDS emigrant ship was ever lost (Sonne 58–60, 148–59).

Several unique occurrences set the voyage of the International apart from other emigrant ships. There were seven births during the fifty-four day crossing, the highest number recorded on any LDS emigrant ship. Five marriages were performed. Only seven deaths occurred, a relatively small number for a large ship carrying families composed of three or four generations; all of the deaths were older people or very young babies. Most singular were the forty-eight baptisms that took place. All the non-LDS passengers (twenty-five) and twenty-three of the crew, including the captain and his two mates, received baptism. Two blacks were among the baptized crew members. The proselyting fervor that led to so many baptisms created a feeling of goodwill among crew and passengers such that love and unity prevailed to a degree rarely seen on such voyages. Arthur recorded:

The captain is truly a noble, generous-hearted man; and to his honour I can say that no man ever left Liverpool with a company of Saints, more beloved by them, or who has been more friendly and social than he has been with us; indeed, words are inadequate to express his fatherly care over us as a people. (Millennial Star 1853, 359)

Arthur and Lyon ordained Captain Brown to the office of elder in the Church and indicated that they hoped to baptize his wife while in New Orleans. These successful missionaries on the high seas invited Captain Brown and the crew to accompany them to the valley, but economic demands kept most of the crew bound to the ship.

The LDS emigrants viewed the many conversions as a manifestation of spiritual approval by the Lord; through their faithfulness the Lord had added new proselytes to the fold. Captain Brown himself had “seen” his baptism in a dream while in the mid-Atlantic and, after attending the regular preaching and testimony meetings, finally decided to join the church that brought so much harmony to his ship (Hartley 9). Christopher, Arthur’s son, was baptized on April 9 and was confirmed a member of the Church by Lyon. The baptisms took place in a large vat of sea water on the main deck. Lyon baptized some of the crew members with whom he had struck up a friendship as they listened to and discussed his preachings in the nightly church meetings while at sea.

The proselyting successes of the International’s passengers were touted in the Millennial Star. Using his own diary and adding a few details from Arthur’s sketchy record, Lyon prepared for publication an account of the trip. It was likely designed to give future LDS voyagers the details and the flavor of the journey, in much the same way as William Clayton’s 1848 Emigrants’ Guide had enlightened those preparing to cross the American prairie. The result of Lyon’s editing was an eight-page pamphlet published in Keokuk, Iowa, while he was waiting to start the trek across the plains. Quotations from the published version and the original diary differ in many details:

| Lyon’s diary | Published account | |

| Mar 9 | Sailing at a quick rate but in the wrong direction. | Strong west wind; heavy sea. |

| Mar 12 | (No corresponding entry) | Remarkable dream of Captain Brown that himself, mates, and crew were all baptized in the Mormon faith, and when he awoke he found himself at prayers. |

| Mar 13 | Rather gloomy day with slight showers; which prevented our meeting on deck. | North wind; very calm mild weather; three meetings. |

| Mar 15 | Fair weather. Most of the Saints recovered from sickness. | Very fine weather. |

| Mar 18 | The sun sand most beautiful, painting all the glories of the western world, as he dipped his barnished forehead in the western ocean. | (No corresponding entry to this poetic description of the sunset) |

| Mar 21 | Still stormy. In the evening it sank to a calm. Southwest wind. | Fine weather—all drawing sail to best advantage—meeting in the evening, addresses by several of the Elders. |

| Mar 26 | A counsil (sic) meeting held to settle a cooking dispute. | A council meeting held to settle a cooking dispute, which was settled amicably. |

| Mar 31 | (long paragraph on problems of water distribution and rationing) | (No corresponding entry) |

| Apr 16 | Held meeting on the poop deck, a great many of the Saints were present; had some teaching on the principle of being liberal. | Held meeting on the quarter deck, great many of the Saints present. |

From Lyon’s diary, it is obvious that the trip had the usual minor disputes over water, cooking, and fire privileges. The storms, especially in March, were fearful and life threatening—on one occasion “the luggage on the larboard side broke their moorings and rolled to the centre of steerage,” causing panic in the lower cabin. Most of the travelers were seasick at various times. Some days the writing in Lyon’s diary is very sloppy, likely due to the tossing of the ship in rough seas. Arguments over rights must have caused the April 16 discourse on “being liberal” and accepting other points of view. Many days were monotonous; to fill up the hours Lyon often recorded the minutest details in poetic description. On one occasion, the passengers were ordered to keep all dogs chained and to clean up their messes. The published account of the voyage eliminates most of these unpleasantries and normal problems, emphasizing the daily prayer and preaching meetings, the spiritual relationships, and the baptisms. The account even makes the weather finer than it really was. This public rendition seriously distorts the rigors of the journey, giving it the appearance of a pleasant Sunday afternoon jaunt rather than detailing the ofttimes anxious, painful crossing that it was for so many passengers. The account was obviously designed to ease the anguish that British proselytes might feel about gathering to Zion.

Lyon and his family had boarded the International on Monday, February 21; however, the square-rigger did not hoist her sails until the following Monday, when a steamer towed her twenty miles out to sea and favorable winds started her on the 5,000 mile “uphill” (against the prevailing winds) voyage to New Orleans. For fifty-four days, from February 28 through April 23, the passengers rolled, tossed, and pitched toward America. One storm was so violent that it caused a huge water spout to form on the sides of the ship. Seasickness was common, especially during the first few turbulent days. Counselor Richard Waddington was violently seasick during the entire journey; Lyon never mentions that he or his family members were even mildly nauseated. Storms and contrary winds so slowed the crossing that after five weeks only 2,400 miles had been logged, an average of less than 70 miles a day. Consequently, Captain Brown rationed the water and reduced food quantities. Arthur and Lyon called a special meeting on April 3 in which “a proposition was made that we should pray . . . for favorable winds, when remarkable to relate the Lord almost immediately answered our prayers” (Lyon Diary). The final 2,600 miles were covered in twenty days, an average of 130 miles a day.

The 425 passengers met nearly every evening for prayers and preaching. Lyon was the most frequent speaker in these spiritual assemblies, followed by President Christopher Arthur. Non-LDS travelers and crew members attended, and Church members soon began performing a few convert baptisms two or three times a week. The proselyting zeal acquired in Scotland and Worcestershire followed Lyon on the ocean; he continued blessing babies, preaching daily, baptizing, and confirming. Some Saints were rebaptized and at least once, on April 8, “president Arthur Baptised some for their health” (Lyon Diary). The ship’s presidency organized open meetings in which anyone could testify. On March 28, “a sister prophesied conserning [sic] myself and wife, that we would be blessed to see and enjoy the good of Zion.” Another “woman spoke in tongues revealing the mind of God” (Lyon Diary, April 19, 1853). It is obvious from these incidents that both men and women had the privilege of spiritual prophecy; the women seemed especially adept at interpreting the Spirit.

The most gala day of the voyage was April 6, on which all the ship celebrated the organization of the LDS church. Six rounds of musketry heralded a morning of ceremony, dancing, and singing. President Arthur, his two counselors, and not-yet-Mormon Captain Brown presided over the formalities in which twelve young women, twelve young men, and twelve “venerable old men,” dressed in white and holding Bibles and Books of Mormon, paraded on the deck. In the afternoon the Saints again prayed, praised God, sang, danced, recited poetry, and played musical instruments. Lyon and others read poetry written especially for the day and sang original songs to the tune of “Yankee Doodle.” An exaggerated sentence, not in Lyon’s diary but in the published version, indicates that they had “a repast of every delicacy the ship could afford, or pastry cooking invent.” The joviality, a necessary release from the cramped quarters and monotony, continued until late into the evening; “it was a day of great harmony and mirth, such as many of the Saints never before experienced” (Lyon Diary).

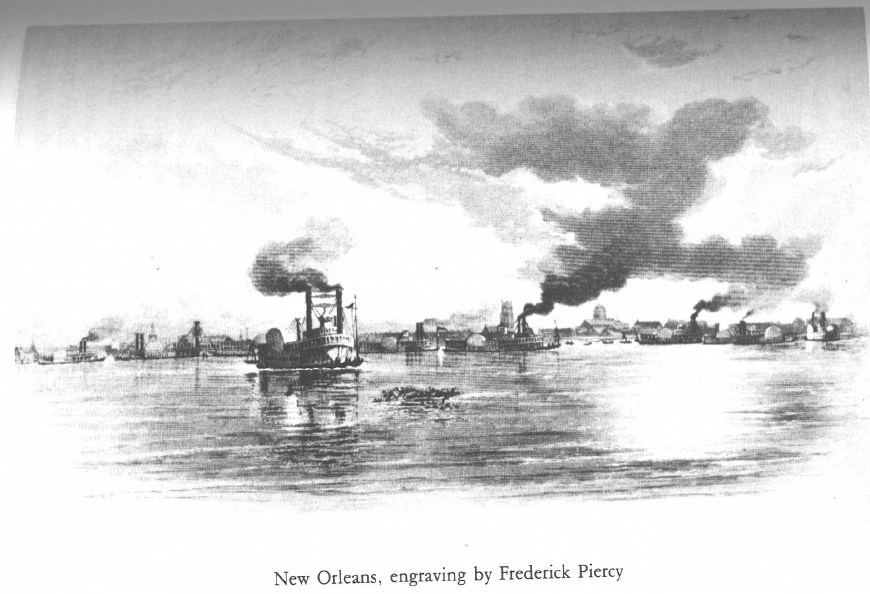

As the ship drew closer to America, Lyon saw a lighthouse from Cuba and felt the completely unaccustomed tropical climate: “excessive heat, 110 degrees” (Lyon Diary, April 19). The astonished passengers had caught never-before-seen fish and sharks, had seen a whale as well as a miraculous waterspout, and had thrilled at one of the most congenial LDS emigrant voyages on record (Sonne, 63). Just three days from New Orleans, Captain Brown was finally baptized . . . in his own bathroom. On April 23, a steamer tugged the International 110 miles up the Mississippi River, where it docked in New Orleans port at 5:00 P.M. An American doctor came aboard, briefly examined the passengers, and pronounced them ‘hearty and whole,” fit to enter the United States of America as permanent residents. No visa or other permission was necessary; their residence in America would make them citizens.

Captain Brown warned the emigrants about the dangers of sickness in New Orleans, urged caution with fresh fruits and vegetables, and ordered a watch to prevent sharpers who might steal the voyagers’ goods or cheat them of their money. For four days the wide-eyed emigrants tarried in New Orleans, visiting Bourbon and Royal streets and—above all—marvelling at the newness, the contrasts, the people. In 1853, New Orleans was the fourth-ranking port in the world and the second busiest in the United States. Its 130,000 inhabitants lived in aristocratic luxury and filthy poverty. Slaves were evident everywhere, and a spirit of bustle and fast-moving commerce, akin to that seen by Lyon in his earlier days in Glasgow, filled the streets. Lyon’s working “friend” from his teenage days, cotton, waited to be loaded on the International for her return to Liverpool; the abundance of sugar, also bound for Great Britain, awed the Lyon family, who had used sugar only on special occasions. Years later, Lyon recalled his introduction to America:

T’was New Orleans, where first I landed . . .

Where I came from, t’was preaching prayer all day.

But here, it was all laughter, dance, and jest,

And sports and plays of ev’ry kind the best,

Great dancing halls, slave markets, and what not,

Were all astir; people a mixed lot;

Black, brown, and yellow, some a darker white,

All ladies too, dressed gay, but something very light. [9]

For five days the Lyons smelled, tasted, heard, saw, and touched the previously unimagined sensations of New Orleans—lighthearted gaiety mixed with the heavy pain of human beings for purchase by other human beings. New Orleans food provided exotic relief from the ship’s fare, but the late April heat seemed to oppress and the humidity to smother them. A moderate meal at a restaurant cost a mere five cents a person, but the Lyons generally stayed close to the ship, fearing malaria, which in New Orleans claimed as many as 200 people a day in the summer of 1853 (Piercy 161).

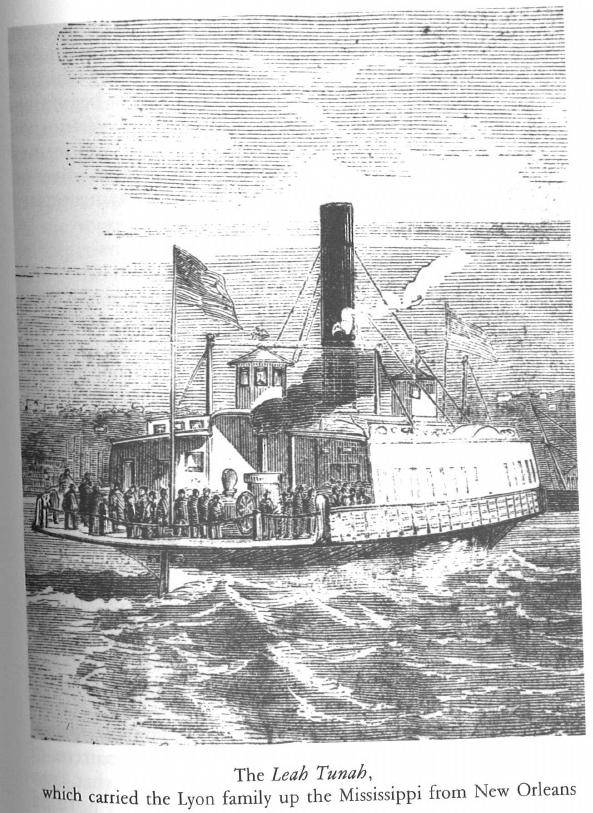

On Sunday, April 24, the emigrants held their last meeting aboard the International and were honored by Captain Brown and his wife. Christopher Arthur and LDS church agent, James Brown, split the company into two groups, naming Lyon to head the 237 Ten Pound Saints; Arthur himself commanded the smaller ordinary contingent. Arthur entrusted the remaining Perpetual Emigrating Funds to Lyon. When the money was later counted, £20 were missing; “Elder Lyon felt very bad and thought that [Arthur] would think he stole it. . . . Brother Lyon hardly got over it” (C. J. Arthur Diary, 5, 12). The burden of carrying all the money weighed heavily on Lyon. He ceased making daily entries in the logbook and began recording every cent and pence paid out. Dollars and pounds were accepted with equal value. Lyon records that he received “money in hand—gold—248 pounds” in New Orleans. He paid £104 for the company’s passage to St. Louis and bought cheese, biscuits, and pork for the journey. At 4:40 P.M., Wednesday, April 27, the Ten Pound Company boarded the Leah Tunah, a twin-stacked, side-wheeler Mississippi steamer to begin the noisy, smokey 1,200 mile trip to St. Louis. For eight days the paddle-wheeler chugged upstream at about six miles an hour, stopping twice daily to replenish its fuel—wood which was supplied, stacked, and sold by local farmers. The Perpetual Emigrating Fund passengers were crowded below deck in steerage class without food, bed, or toilet. They slept on crates, on the damp deck, and on makeshift beds; they improvised (Picture: The Leah Tunah, which carried the Lyon family up the Mississippi from New Orleans) meals as best they could. With little perceptible motion, the river slipped by the steamer night and day in an endless stream. Lyon obviously had many free hours during which he “doodled” in his record book, thinking of his beginnings in a new land: the words George Washington, Mississippi, New York, America fill up three entire pages; Lyon seemed to take particular delight in writing the name of the river on which he was traveling. Another miscellaneous fragment noted

Smooth runs the water

Water where the brook

is deep.

Perhaps thinking on his own economics, Lyon carefully penned:

Blessed are the poor for

they shall inherit

the earth.

The unaccustomed heat continued to smother the new Americans. On Sunday, May 1, Christopher J. Arthur fretfully noted, “Thermometer 98 degrees nearly Blood Heat,” as if he feared that his body could not stand such a temperature. Yet his diary notes that it was “a beautiful day,” that a “stove was lighted for a few hours for breakfast,” and that the group was congenial. The newness of river travel, of the sights and customs, of life in America—all sunk deeply into Lyon and his band. Slavery and the presence of so many blacks elicited conversations and even condemnation of a country so progressive yet still practicing such an antiquated pattern of human bondage. Here the blacks did much of what Lyon called “Irish work” in Scotland; other passengers justified slavery because “negroes were truly inferior animals to white men” (Piercy 75). As in past occasions, Lyon championed and defended the poor and oppressed.

The passengers marvelled at American ingenuity and the “go-ahead” attitude that produced important inventions. Piercy, for example, extolled the modern American stoves, which made cooking so much easier, and the amazing new zinc-covered washboards, which did not shred the clothes as washboards with wooden ridges did. The passengers saw that “Americans are as quick at eating as they are at most other things. . . . It is, doubtless one cause of the universal complaint of indigestion, to which the general habit of eating bread hot from the oven contributes not a little” (Piercy 78). Some of the voyagers felt that they got sick from the new foods; all experienced some homesickness. James Farmer reflected that “the scenery at this time reminded us of our native land” (Part 1, 99).

The Leah Tunah stopped at Memphis, 750 miles from New Orleans, where Lyon and Waddington again counseled and worried about money and provisions for the hungry river travelers, purchasing “205 lb of Biscuit, 51 lb of Butter, 51 lb of Sugar” for $24.50. Some of the Saints still complained about the food; the unifying daily meetings on the International were not possible now, and small dissentions magnified. In the early evening on May 5, the side-wheeler slipped quietly into the St. Louis docks. The passengers unloaded their scanty chests and slept on them, a necessary protection from thieves as well as a way to obtain a dry place to sleep. Quite by chance, Lyon met the man who had baptized him, his dear Scottish friend William Gibson, and began to feel that the elect had truly fled Babylon and were now here in this new home. The bustle of gentile St. Louis was temporarily laid aside; the Mormons were now congregating.

The next morning, the tired, ragged group boarded the Jenny Dean, a smaller paddle-wheeler, enroute to Keokuk, Iowa. Lyon paid £49 for the entire group to make the 200- mile trip. For two more days the steamer traveled slowly upriver, stopping at Quincy, Illinois, to purchase more food. Lyon heard frequent complaints about shortages of food and water as well as about soggy biscuit and no chance to light a fire to cook the few pieces of available meat. On Sunday morning, May 8, the Jenny Dean eased into the busy docks of Keokuk. More than 6,000 miles of ocean and river were memory; now the real trial by walking would begin. Yet, Keokuk was a resting place, a change, a chance for renewal, regrouping, rededication.

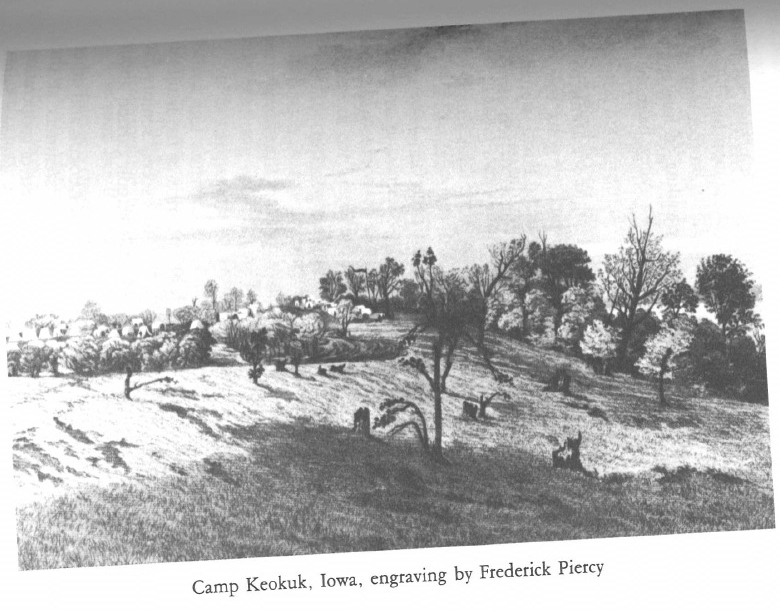

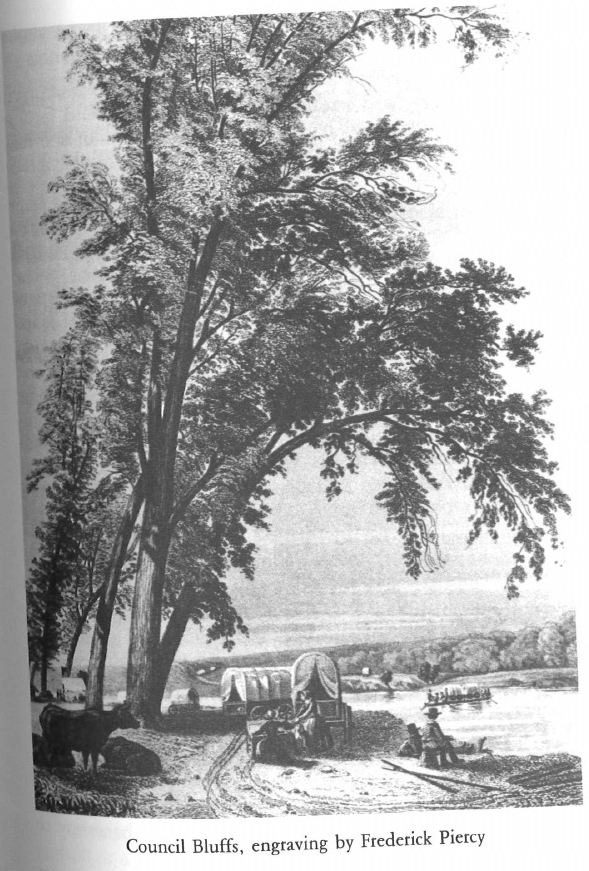

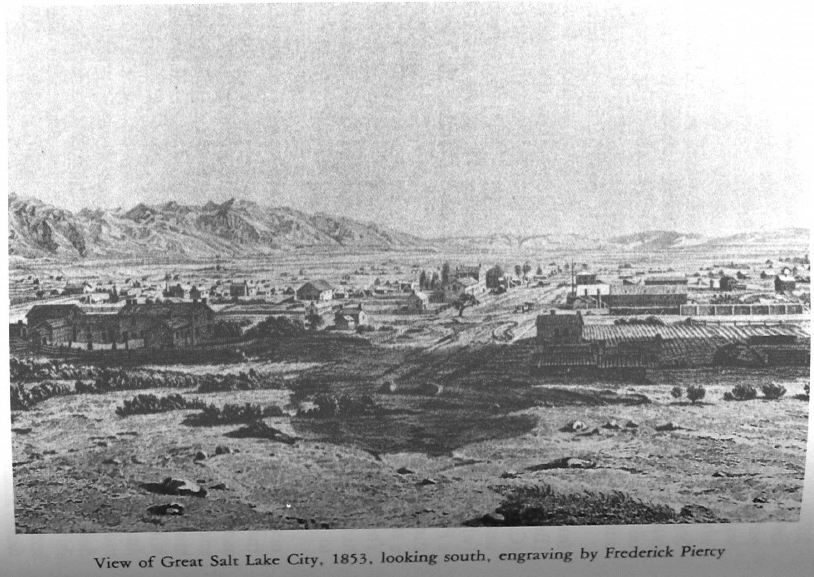

During preceding years, Mormon emigrants had steamed up the Mississippi River to St. Louis, transferred to a Missouri River queen, and gone to Council Bluffs, at the extreme western point of Iowa. As a result of the flood of LDS emigrants and California and Oregon-bound overlanders, however, merchants and traders around Council Bluffs and Kanesville had raised prices to such inordinately high levels that Isaac C. Haight, who in 1853 was the Church agent in charge of emigration over the plains, selected Keokuk as a new jumping-off point (Piercy 201). This decision added more than 300 miles to the overland journey, but the savings in cost, especially to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund companies, justified the decision. Haight concluded that Keokuk was a healthier spot than Council Bluffs and that it would prove a wiser place to begin the route. The town’s proximity to Nauvoo, Illinois, just twelve miles upriver, also may have played an emotional part in Haight’s choice. Haight directed the Saints to a large staging ground on the river bluffs, a half-mile north of downtown Keokuk (Kimball 428). Hundreds of other emigrants had arrived previously; hundreds more would come during the rest of May. Most of the 2,312 emigrants sailing from Liverpool congregated there, most of them planning to make the sea and land journeys in a single, albeit long, season.

While still aboard the International, the Lyon family and others had sewn tents and wagon covers of twilled cotton purchased in England. Once settled in camp, they pitched their tents, their homes for the next four weeks. Housing was now no problem. Money problems, however, continued to plague the party; there simply was not enough Perpetual Emigrating money left to buy wagons, oxen, and provisions for all the Ten Pound Company. Haight had already purchased 450 yoke of oxen, 250 wagons, 300 cows, and provisions for four months for 2,500 people with $40,000 in gold and drafts he had brought from England (Journal History, August 29, 1853). Yet this was still insufficient for all the Mormons, and so Haight

asked father [Christopher Arthur] to help him out. Father told him he had divided his means among his children. If they were willing he could have $1,000. Brother Haight came to me and I said I was perfectly willing to loan my part. Brother Haight on arriving in the valley paid the loan. (C. J. Arthur 59)

With these and other dollars, Haight set about buying, making, and remodeling the 300-plus wagons that were needed for the 1853 Perpetual Emigrating Fund overlanders. The 1853 food allowances for each wagon of ten emigrants were as follows:

1,000 pounds flour

50 pounds sugar

50 pounds bacon

50 pounds rice

30 pounds beans

20 pounds dried apples, peaches

5 pounds tea

1 gallon vinegar

10 bars soap

25 pounds salt

This amounted to at least 1,300 pounds of foodstuffs in each wagon plus personal items not to exceed seventy-five pounds per person, meaning that each wagon carried about a ton of supplies and personal items.

Many of the men in camp took jobs in Keokuk and other nearby towns, building roads, unloading steamers at the docks, repairing fences. A congenial atmosphere of cooperation and mutual benefit developed between the anxious Saints and the local businessmen, who prospered immensely. The Mormons bought oxen, cows, wood, nails, powder, coffee, flour, canvas, clothing, axes, chains, boots, zinc, and scores of other necessities for the four-month expedition to the valley. But food for the weeks of waiting and organizing also had to be obtained. Some hunted birds and squirrels; others fished in the Mississippi; some bought foodstuffs from local farmers.

Lyon apparently did not keep a diary at this time. Information about the month-long wait in Keokuk comes from the diaries of other expectant travelers—Christopher Arthur, his son C. J., and James Farmer. As in the past, Lyon was immediately assigned a leadership role; on May 9, Haight appointed him “captain of fifty” in the camp (C. A. Arthur Diary). Lyon had to buy and distribute the food; he made Christopher J. Arthur his assistant, and together they dealt out “7 lb flour, 1/

The first few days in May were chilly, but by mid-month temperatures had risen along with the Saints’ desires to depart as soon as possible. Haight realized that he would have to stagger departures so that the various companies would not interfere or compete for the same resources on the trail. But the weather would not cooperate—rainstorms kept the prairie soaked such that heavy wagons would bog down and hungry oxen would pull grass up by the roots and get muddy mouth-fuls, resulting in sickness. The wait continued.

Lyon’s acquaintance from Great Britain, Frederick Piercy, visited and sketched the assembled Saints:

The Camp was in excellent order, and the emigrants informed me that when the ground was not muddy they would as soon live in a tent as a house. I saw few idlers. . . . The emigrants from each nation [English, Scottish, Welsh, French, Dutch, Danish, Irish] had wisely been placed together and those who crossed the sea together were still associated as neighbors. . . . I was told that the general health was good. . . .

Guards were selected to stand watch at night. . . . A council of the whole Camp had . . . jurisdiction in all cases of dispute or of conduct unbecoming Saints. (Piercy 91, 201

All diarists expressed amazement at the general good health of the camp, likely having heard horror stories of cholera and other community diseases. The waiting Saints prayed together each night, testified on Sundays, and preached Mormonism to their new friends in Keokuk. Along with other camp leaders, Lyon spoke in nearly every meeting. By Monday, May 16, Lyon’s company had eighteen wagons, and he “purchased wood and nails—for making the sides of the waggons” (C. A. Arthur Diary). The obvious shortage of wagons caused Haight and others to purchase flat-bedded vehicles which were then remodeled to accommodate wooden sides and canvas covers.

Still awaiting final preparations and better weather, camp leaders encouraged all literate Saints to keep diaries. Arthur wanted to set the example and, on May 21, mentioned the “proof sheet of [his] Diary punctuated by Elder Lyon” (C. A. Arthur); apparently Lyon’s literary reputation provided work for him as he edited diaries of others in the company. The same day Arthur noted, “Heavy rains. Prayers by Elder Lyon.”

On the twenty-third, Arthur, Lyon, and Waddington undertook a small business venture—the selling of diaries to Saints and Gentiles: “Sold between 7 and 8 dollars worth Diarys. Waddington owes me 60 cents. Brother Forsyth insulted Elder Lyon. . . . Sent 450 Diarys. . . . I was to have half the profits, Brother Lyon 3/

While the members of the company waited in camp, surrounded by more than 1,000 strangers, tensions mounted and conflicts ensued:

A council meeting of the priesthood called, in consequence of Sister Newton offending father Waugh, in defending himself he unfortunately hurt her mouth. Her husband had been stocking him. Brother Newton struck father Waugh. All parties were reconciled. (C. A. Arthur, May 23)

On another occasion, Cyrus Wheelock, a friend from Lyon’s mission days in England, was “exhorted to keep the word of wisdom,” and a resolution was passed that “any Brethren be disfellowshipped that were found intoxicated. All thieves be left on the plains” (C. A. Arthur, May 15).

As the May weather gradually dried, the Saints’ anticipation grew. The dominant, heavy C. A. Arthur made a necessary sacrifice and “sold my Bed and pillows for V/

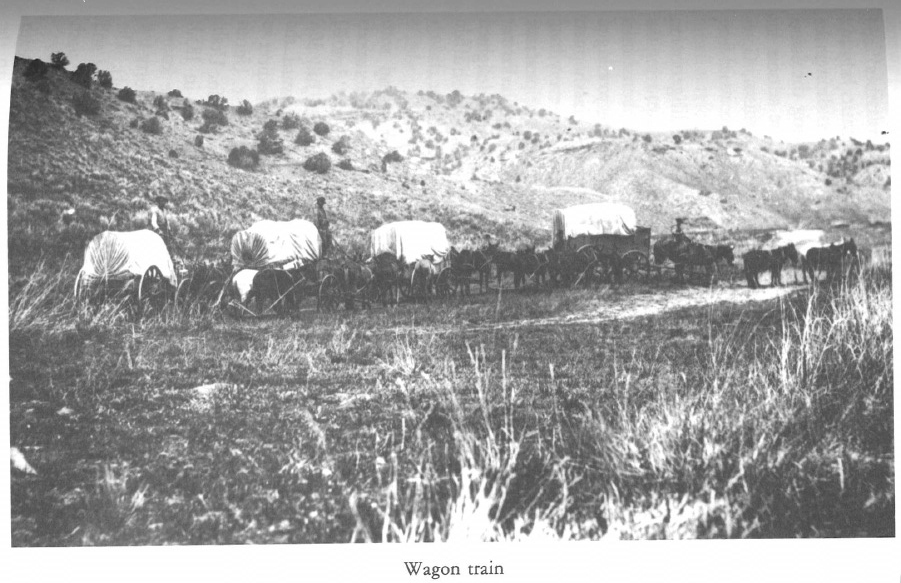

At long last, after twenty-eight preparation days in the camp, fifty Saints under the command of John Lyon left Keokuk at 10:00 A.M., on Thursday, June 2. James Farmer, in the advance camp near Montrose, notes that “Gates left us to fetch a [Ten Pound] company from Keokuk. . . . About sun down we had a heavy storm Thunder and lightening and rain which continued all night rained through our tents and wagon covers” (Farmer Diary, June 2, 1853). The old enemy, rain, again thwarted Lyon and his charges on the first day of the 1,344 mile trek to Utah. Piercy observes that the spring of 1853 had brought higher creeks and rivers “than was ever known since white men” had come to the area (202). John Unruh also found 1853 to be the wettest year for overland migration; it slowed the travelers down in Iowa but produced commensurate advantages in the arid West, where oxen found grass in usually dry places (322). The most vexing problems the Gates companies experienced during their trek through Iowa were swollen rivers, cavernous mud holes, and near-impassible roads. “Roads were very bad,” “got stuck in the mud,” and “road very bad worse than ever I had seen” are frequent diary entries. But the soggy Saints moved steadily along. After three days of regrouping in Montrose, they began regular travel, averaging nearly twelve miles a day on the 307-mile mud-trek to Council Bluffs. They traveled every day of the week; on Sundays they usually only hitched up the oxen for half a day, leaving the morning free for washing, baking, resting. The company’s rather late start in the traveling year, when combined with the 300-mile handicap tacked on to the beginning, required that they use every possible day to its fullest. One day the Saints trekked twenty-five miles (Farmer Diary, June 28), their top record; three miles represented their shortest day (June 26).

The first goal in everyone’s mind was Council Bluffs, or Bluff City, the fabled and tragic gathering spot of the first Mormon pioneers (see map 8). As they left Keokuk and Montrose, the Mormons traveled past a few villages, including Charleston and Farmington, but always tried to avoid settled areas. Firewood, water, and grass for the animals are the three urgencies regularly mentioned in all diaries. Wood, water, and grass continued to be the voyagers’ primary concerns for the remainder of the journey. A group of Danish Saints, the John Forsgren Company, was already on the trail ahead of Lyon and his fellow travelers. Cyrus Wheelock and company were right behind them and occasionally caught up and passed them while they were taking a noon rest/

After twenty-nine continuous travel days, the Gates Company wearily rolled into Bluff City on June 30, to rest, regroup, and ferry wagons and animals over the slough-ridden, swollen Missouri River. The Lyon family had held up very well during the arduous month. Lyon had been quite used to walking in Great Britain while working on newspapers and carrying out missionary activities. His wife experienced difficulty with blisters and sore legs but showed great courage. The children seemed to revel in the experience. Ann (age twenty-two now) helped with Matthew (age ten) and Mary (age eight), who often hitched a ride in the wagon. John Jr. (age eighteen) usually drove the family wagon; Lilly (age sixteen) aided her mother with the smokey cooking and frequent washings. Lyon spent most of his time organizing and aiding others, to keep the eighteen wagons in his charge moving as a unit.

The two-week stay at Council Bluffs provided the necessary rest for bodies to rebuild themselves, sore feet to recover, and provisions to be readied. Arthur bought and disbursed an additional 100 pounds of flour, ten of bacon, one pound of sugar, one-and-a-half pounds of tea, one-and-a-half of soap, and some salt and currants (raisins) to each wagon in the Ten Pound Company. Meetings were held to reorganize for the longer trek to the valley. On Sunday, July 3, Isaac Haight, who after dispatching the companies from Keokuk, had steamed down to St. Louis and upriver to Council Bluffs, “proposed and moved that Lyon be chaplain” (C. A. Arthur) of the entire company, of some 267 Saints. He willingly accepted the assignment, which consisted of being the spiritual leader of the company, calling them for morning and evening singing and prayers, preaching in all meetings, conducting prairie funerals, and anointing and blessing the sick. Frederick Piercy, now in a company just three weeks ahead of Lyon, observed that in LDS pioneer companies

the voice of prayer was heard every day, and the song of praise at the rising and setting of the sun. Many a hard feeling was then destroyed by the melting influences of spiritual instruction, and resolves to amend were made, which doubtless resulted in a better life. (104)

At the meeting presided by Haight, Lyon “was also appointed Captain of hundred” (Farmer, July 3), a further indication of his abilities to organize and motivate.

C. A. Arthur noted July 4 as “Anniversary of the independence of America (no cases of drunkeness).” Farmer recorded that “the inhabitants of Bluff City had a public dinner. I went to the City for a short time and rejoiced to see the people so happy.” The minor reverie was a patriotic boost for the fatigued, sometimes impatient, travelers.

A frequent problem while rolling through Iowa, as well as in camp at Council Bluffs, was how to appoint and control guard duty; some men had slept while on watch; a few had refused to serve. As a result, cattle had frequently strayed, and valuable time was lost in their retrieval. As the group prepared to depart westward, “Brother Lyon [was] appointed by Elder Gates to see after the Watch” (C. A. Arthur, July 10). To his prior multiple duties was added the increased work of appointing and assuring the proper functioning of guard duty. Occasional complaints about noncompliant guards still appear in scattered diary entries but not with the frequency mentioned in Iowa. Each adult male had from three to four hours of duty at least twice a week. The difficulty of staying awake half the night, or arising at midnight after a very full day of walking, pushing stuck wagons or searching for stray cattle, was a tremendous physical drain on all the men. Lyon was most successful in organizing and bringing harmony to an extremely difficult duty.

Four days were required to ferry all the wagons across the swampy-sided Missouri River; two more days saw all the cattle across. Arthur and Lyon paid the usual but very costly $1.50 per wagon to the ferrymasters. Once the 267 Saints of the large Gates Company were all across, “a few gallons of whiskey were drank,” to celebrate as well as to warm “many of the Brethren [who] were up to their necks in water and mud whole of the day” (C. A. Arthur). On Saturday, July 16, at 9:00 A.M. “Elder Gates gave orders for us to start” (Farmer), and the Mormon overlanders began the final 1,031 mile lap of their journey to the Great Salt Lake Valley. They were a minor part of the 5,000 Mormons who pushed into Utah in 1853, and the 27,500 non-LDS who went on to Oregon and California that year (Unruh 85). Far from being lonely and isolated, emigrants crowded the broad trail, which was often a mile wide through Nebraska territory. Most of the travelers had preceded the Gates Company by several weeks; consequently, Lyon and his trailmates often found grass and firewood depleted. That same year drovers had already pushed more than 300,000 cattle, horses, sheep, and mules along the route to satisfy the agricultural needs of the new settlers on the West Coast; the Fort Kearny register notes 1853 as a peak year for livestock on the trail (Unruh 334). Not only were resources drained, but mud, ruts, and often times dusty trails resulted. Gates carried William Clayton’s Emigrant’s Guide and recognized that his own company was beginning more than three months later than Brigham Young’s pioneer group and was traveling over a now-worn trail—one with many new problems. Money continued to be a serious concern. Each wagon paid a dollar to be ferried over the Elkhorn River (July 18), another dollar and twelve hours of waiting to cross a fork of the Platte River on ferry (July 22), and similar amounts to cross streams and rivers all the way to Utah. Enterprising emigrants had set up ferries and supply shops all along the trail, where overlanders could replenish their foodstuffs at inflated prices.

A routine day during the early part of the journey began at 4:00 or 4:30 A.M., with a prayer. Breakfast in family groups came next and then the women prepared the food for the day and the men rounded up the ever-straying oxen, yoking up the teams for an 8:00 or 9:00 A.M. departure. The group then traveled for five or six hours, before stopping at a convenient grassy spot for dinner. By 3:00 P.M., the group was again plodding westward for four to six more hours, beholden only to the vagaries of where to find grass, wood, and water for the night. At 8:00 or 9:00 P.M., Gates called a halt, the women served a light meal, and the used-up Saints washed dishes, sang a song, prayed, appointed a contingent of boys and men to watch over them, unyoked the tired oxen, and eased their aches between dirty blankets. The day was sixteen or seventeen hours long, but only ten or eleven hours were actually spent traveling. Taking into account the few rest days on this longer leg of the journey, the Gates Company averaged approximately 14.5 miles per day over the next seventy-seven days, or slightly over one mile per hour! The reliable but plodding oxen moved much slower than a person could walk; long waiting at ferries, mutual assistance when a wagon got stuck, and double-teaming up steep hills—all combined to thwart rapid progress. Frederick Piercy, in the better-prepared Miller/

Sunday, July 24, was a day of complete rest and celebration for the emigrants. Farmer notes:

Fine morning spent the day in washing &c. I and Brother Cook and Lilly cut down wood to make an ox yoke at 3 we held a meeting. Elders Lyon, Waddington and Gates addressed the Saints and gave excellent teaching which caused us to rejoice. . . . Most of the saints felt worn out for the want of rest as many had not slept for several nights owing to the mosquitos but the Lord sent an East Wind and blew them away and we got a good nights rest.

After eight days of continuous travel from the Missouri River, many of the company were exhausted; by staying in camp an entire day, their bodies recovered and their spirits rose. Some of the men fished to supplement the now-tedious diet of bread, bacon, and coffee. During a meeting, “Brother Lyon exhorted to general obedience”; the more-experienced Jacob Gates “observed that we was amongst the Pawnese [Pawnees] Nation, the meanest of the American tribes” and urged caution in straying from camp (C. A. Arthur, July 24). Gates also projected that he would “eat his dinner the fifth of October in the Valley [with] Lyon,” giving the Saints for the first time a target date, albeit late in the season, for their arrival in Zion. Despite the public optimism, Gates knew he would have to hurry the wagons along to avoid frost and early snows in the mountains.

Gates complimented the men for their diligence on guard duty as well as for their new-found skills in moving the headstrong oxen along. They also heard new, sometimes horrifying sounds; all diarists record the terrifying yowling of wolves at night. And new animals abounded—grasshoppers (“another heavy swarm of grasshoppers at this time everything is covered and millions in the air they have the appearance of snow we never saw such a wonderful sight,” wrote Farmer on August 19), lizards, antelope, and prairie hens all delighted the British immigrants. On August 3, the camp saw buffalo for the first time and carried out the obligatory hunt, bringing back two of the gigantic beasts to share.

An occasional Indian party ventured into camp with positive results for both groups. The Indians were not ferocious and hence are seldom mentioned in the diaries. “Saw 12 Indians they smoked and took oath” (C. A. Arthur, July 30). Never did these Saints express fear or anger toward the Indians. The year 1853 was one of the safest with respect to Indian/

The natural phenomena of birth, sickness, and death traveled with the company. From June 6 to September 30, the days on which the Lyon family departed from Keokuk and on which they arrived in Great Salt Lake, eight deaths and three births occurred in the company. [11] Four of the deaths were young children; four adult males also died; not a single adult female in the company was buried on the prairie. Most of the deaths took place toward the end of the journey in late August or September. When a company member died, the pressured company could stop only long enough for a short burial service. As chaplain, Lyon officiated in a brief graveside prayer and sermon for each of the deceased, and then the main group quickly moved on, allowing grieving parents or friends a few minutes to mourn in silence and then catch up. Nor was much more time or comfort alloted to the three mothers who stoicly delivered babies during the trek. The brief entry in Arthur’s diary “BIRTH of a Male child of Brother Hawkins” (August 4) does not even give credit to the travailing mother nor does it mention any delay in the company’s routine for the birth. Life continued westward.

The Saints comprising the Gates Company had escaped cholera and malaria epidemics in New Orleans and on the Mississippi but worried about contacting diseases while on the trail. In 1852, more than 2,000 overlanders died of Asiatic cholera while on the trail to Utah, Oregon, and California (Unruh 346); the Mormons feared the same epidemic in 1853. But 1853 was a much more healthful year, and the Gates Company suffered more from mosquitoes than cholera. “The Mormons, whose passages to Salt Lake City were invariably better organized and included a higher percentage of females, succumbed less frequently to diseases” than non-LDS travelers (Unruh 346). Unruh’s presumption is that the presence of a larger than normal number of females was responsible for better hygiene and thus improved health among the Mormon groups.

C. A. Arthur’s diary notes the minor health complaints of the company, while the other company diarist, James Farmer, mentions the scenery more than the travelers’ illnesses. Arthur records that ague, pulled muscles, fatigue, fever, swelling, and mountain fever plagued some in the camp, but little more than had they been safely settled in a city. On September 16, “Father Haggis broke his leg” (C. A. Arthur); this was apparently the only broken bone in the entire company. The leg was set by one of the group, and the man rode the rest of the way to the valley. An accident and subsequent miraculous healing amazed both record keepers:

Brother John Butlers little boy aged 7 years was trying to hang on the tent pole which was placed along side the waggon he let go his hold and the wheel went over his back there was 2400 lbs in it we administered to him and he was healed to the astonishment of all that saw it. (Farmer, August 4)

The Gates Company felt themselves both lucky and blessed; no fatal accidents occurred to them, and their sicknesses were all minor.

On Sunday, August 21, just a few miles beyond Fort Laramie, Gates made a major decision. Both diarists record the event:

| Farmer | Arthur |

| Little rain during the night but a fine morning spent the time washing and several indians visited us during the day in the afternoon held a meeting opened by Elder Lyon. Elder Gates addressed us all to rejoice after which business was put before us as Elder Gates thought it would be wise to divide the company in 2 parts it was moved and seconded that Elders Waddington and Thistle (Thirkill) take charge of the Independent Compy and as many more as deemed wisdom and that Elder Gates and Mois bring on the remainder of the £10 Company. | Good feed near the Platt Held a council meeting parted the Company. 17 wagons with Waddington and Thirkill, 9 independent and 8 £10. Company—And 16 with Gates and Moyes. . . .Gates addressed the meeting. Lyon closed with prayer. Plenty wood. Washing and Baking health of the Camp improved . . ..(A government officer at our meeting.) |

Jacob Gates realized that the size of the company had been the cause of its slower than expected progress and hoped that by dividing the Saints into two groups both could move faster. He also sought to lessen the obvious differences between the wealthier independent company and the make-do Ten Pound Company—differences so recently evidenced in the former group’s purchases of goods at inflated Ft. Laramie prices. The plan failed to produce the hoped-for added speed, however, and on September 11 the two groups again joined as they approached South Pass.

Meeting other immigrants and exchanging news was a common occurrence on the trail. On July 30, Lyon met his first missionary companion, J. D. Ross. Ross was headed east, having accepted another mission call. The two reminisced in love and friendship. On September 14, the Gates Company ran across Frederick H. Piercy, another of Lyon’s friends from Great Britain. Piercy had completed his commissioned work for the LDS church (sketches of the route, of Brigham Young, of Salt Lake City) and was returning to Great Britain to tell of his positive experiences with the Saints. Earlier, Lyon had met William Gibson in St. Louis, the man who baptized him into the Church; truly America was the gathering place of the elect.

C. A. Arthur recorded on September 9: 1 ‘We have met the mail on these mountains with a Compy of Gentlemen amonst them was Dr. Bernishel [sic] on business to the States of great importance the facts we could not learn/’ Dr. John M. Bernhisel, friend of two Church Presidents and recently reelected delegate from the Utah Territory, was returning to Washington, D.C., to argue the case for Utah statehood.[12] His patient, efficient nature impressed the Gates Company (Barrett 119).

On September 11, the company filled a request from Brigham Young and forwarded to Great Salt Lake the exact number currently in the group: 103 men, 87 women, and 72 children under fourteen, a total of 262 people (C. R. 376:1). The survey also listed

2 mares

1 bull

147 oxen

47 cows

3 lambs

5 dogs

33 waggons

There were now approximately 4.5 oxen per wagon, with eight people dependent on each wagon. President Young had requested the trail survey so that the Saints in the valley could prepare for the arrival of the immigrants that fall. The year 1852, a major year for the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, had surprised the valley Saints with thousands of new residents, and Brigham Young wanted no such surprises in 1853.

Finding food on the trail and then making time to prepare it was a constant drain of energy, especially for the women. Arthur’s diary lists the following purchased goods as part of the diet of the independent company:

| figs | apples | capi maderia | biscuits |

| onions | beef | currants | lime juice |

| yeast | brandy | potatoes | oil |

| essence of lemon | cocoa | coffee | flour |

The Ten Pound Company was not as fortunate and likely did without some of the more exotic items. Lime juice and essence of lemon were essential to fortify the travelers against scurvy. Alcohol may have been intended for personal consumption but also made a fine item for trade with the Indians and barter with other immigrants. Even the previously listed items became tedious after nearly four months on the trail. The Saints supplemented with:

| fish | wild ducks | geese | oxen |

| service berries | prairie hens | hares | mutton |

| milk | buffalo | antelope |

Both Arthur and Farmer record their delight at eating fresh fish, duck, and buffalo. The immigrants also found and butchered several sheep that had strayed from a large herd being trailed to California. When their yeast and baking soda ran out, they substituted saleratus from certain springs. Mary L. Morris, a few days behind the Gates party, recalled, “Our bread we mixed with a piece of light dough, or leven, but often by the time we reached the camping ground, especially in warm weather, it was sour, or in cold weather not sufficiently raised and then we had heavy bread” (Journal History, October 10, 1853).

During the final month of the company’s journey, the cows gave less and less milk. And the oxen wore down as the hills steepened and the animals’ energy depleted. During the first three-and-a-half months of the trek, only three oxen died; during the last eighteen days, twenty oxen and seven cows died, usually from sheer exhaustion. All were eaten, even by the hungry children, who had previously given the animals nicknames and treated them as pets. Arthur carefully records the death of each animal, usually in bold print that is larger than when a child died. The long trail was finally wearing down both animals and humans, and food was frightfully low. Since the first of September, Gates had admonished all the men, women, and children to walk and not burden the animals.

As the travelers approached Ft. Bridger, on September 19, twenty-seven-year-old Francis Crowther died quietly and was buried. Lyon observed the incident and began a poem, “The Desert Grave,” which he later polished and published in the Deseret News:

Alas! is’t here the “pilgrim” lies,

With all his trials past?

The Saint’s unwav’ring faith ne’er dies,

. . . .

In Bab’lon none would make him stay,

This was his heart’s intent,

Tha’ here he sleeps in solitude,

Who kept the camp in merry mood.

. . . .

Ah! if “the righteous scarce are saved,”

Who venture far to roam,

Of home, and dear ones all bereaved,

That are upon their hearts engraved;

O! what shall men receive, depraved,

Who spurn God’s laws at home,

Nor dare the desert, seldom trod,

To gather with the sons of God.

(Deseret News, March 27, 1872, 107)

This poem, like the plodding Saints themselves, projects an optimism, a confidence, and also a condemnation for those who do not venture west; the pioneer spirit was still very present in 1853. The hungry company was indeed performing a trek of greatness. At Ft. Bridger their shortage of food became critical. Valley Saints had ousted Jim Bridger from the fort the previous month for supplying Indians during the so-called Walker War; hence the anticipated food was not available, and the Church’s Ft. Supply had not yet been established. The company walked on, out of flour, coffee, and potatoes—hungry, worried, weak. Mary Morris remembered that “in walking I was so anxious to save the soles of my shoes, that I walked on the grass wherever possible, so that the uppers wore out first” (Journal History, October 10, 1853). The travelers slowly lumbered up the 7,700 foot pass that divides the Colorado drainage from the Great Basin and hurried eagerly down the other side, stopping on the Bear River for a day to “shoe cattle and repair waggons.” There they “met some Brethren from the Valley who told us that provisions was coming” (C. A. Arthur, September 22). Here feed, wood, and water were plentiful, but food was not. Lyon and his companions dobbed thick crude oil on their squeaky wagon wheels from a nearby “Tar Spring” and for the first time in months enjoyed a squeak-free journey.

Even the well-to-do Christopher Arthur also suffered from lack of nourishment. “Many Brethren without food (Brother Moyes let us have some biscuit and Bad oatmeal)” (C. A. Arthur, September 26). No help came from the valley until September 28, when the immigrants “met P. P. Pratt [who] had brought us 200 lb. of flour. We served out 1/