“Not the Good Fortune . . .” (1803–1824)

T. Edgar Lyon Jr., John Lyon: The Life of a Pioneer Poet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 1–58.

“Some men are born to greatness, and others have it put on them, so said somebody. But I had not the good fortune to have either!” With these almost apologetic words, John Lyon begins a short account of his early years. In his account entitled “Forest King, His Life and Writings,” Lyon thinly veils his own identity (Lyon—king of the forest) and sets out a few sketchy details of his early life.

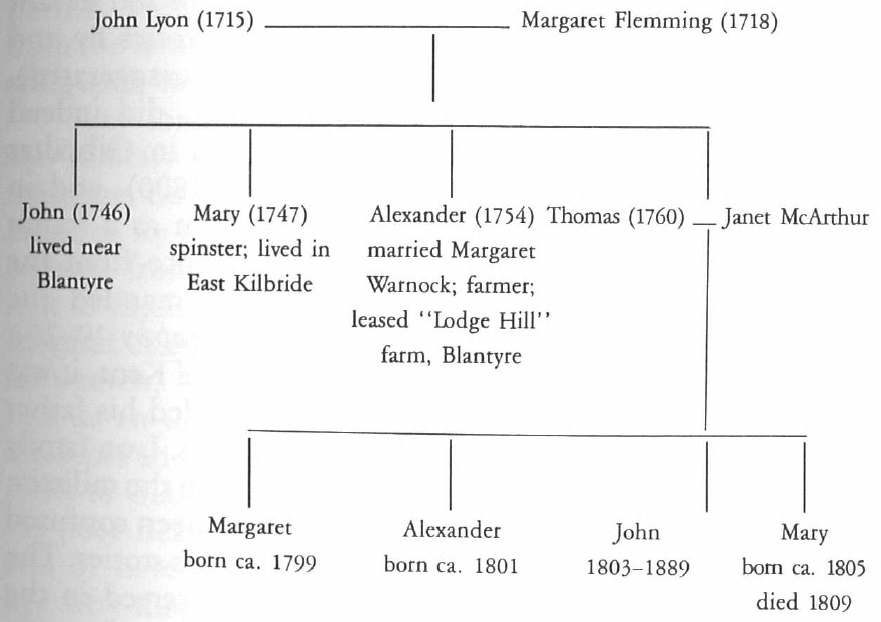

John Lyon was born in Glasgow, Lanarkshire, Scotland, on March 4, 1803. Neither the birth nor a christening is recorded in any of Glasgow’s parish registries, nor on any official documents from the hometowns of his mother or father (mandatory birth registration did not exist in Scotland until 1855). [1] His parents, Janet McArthur and Thomas Lyon, were experiencing severe financial problems in 1803, when the twenty-six-year-old mother gave birth to her son without the aid of midwife or doctor, on a damp winter’s day. Janet had already lost her first two infants, Margaret (born and died about 1799) and Alexander (in 1801), and obviously held great hopes for this new son. He was named simply John Lyon, in honor of his paternal grandfather and perhaps other illustrious John Lyons in Scottish history.

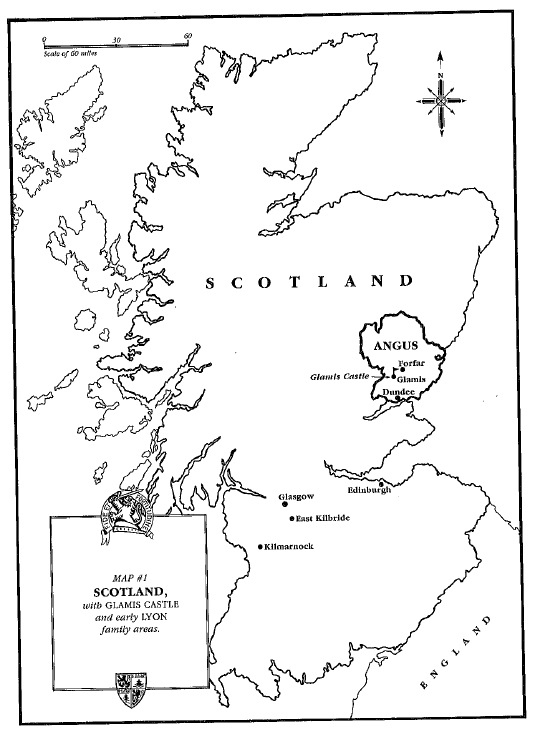

Young John’s progenitors likely came to England from Lyon, France, in 1066 with William the Conqueror. The first Lyon mentioned in Scottish annals is a Thomas Lyon, a crossbowman garrisoned at Linlithgow in 1311 (Ross 1). A relative of Thomas, perhaps a grandson or a nephew, an educated and influential John Lyon was appointed chamberlain (keeper of the royal treasure chamber) of Scotland on October 20, 1377. Two years later, he was also named keeper of Edinburgh Castle, the seat of Scottish royalty. He soon married the king’s daughter and received royal grants of land near Glamis and Forfar, as well as a three-hundred-year-old hunting lodge that had been used by the Scottish royalty (Ross 2–3). For several centuries, the Lyon family grew and spread over both highland and lowland Scotland (Loch Lyon, Glen Lyon, the River Lyon are prominent features bearing the family name). The Lyon family still lives in the old Glamis Castle, near Forfar and Kirriemuir in Angus County. Elizabeth Bowes-Lyon, Queen Mother of Great Britain at the time of this writing, was born in the castle and continues to honor it with her frequent visits (see map 1). Mary Queen of Scots and many of Scotland’s Jameses stayed in the castle, and in time it held so much fame as the most haunted castle in Great Britain that Shakespeare used it for the setting of the ghostly Macbeth. In Perthshire and Aberdeenshire the Lyon family or sept joined with its neighbors to form the Farquharson Clan, whose crest is a lion issuing from a wreath, indication of the family’s importance in the clan.

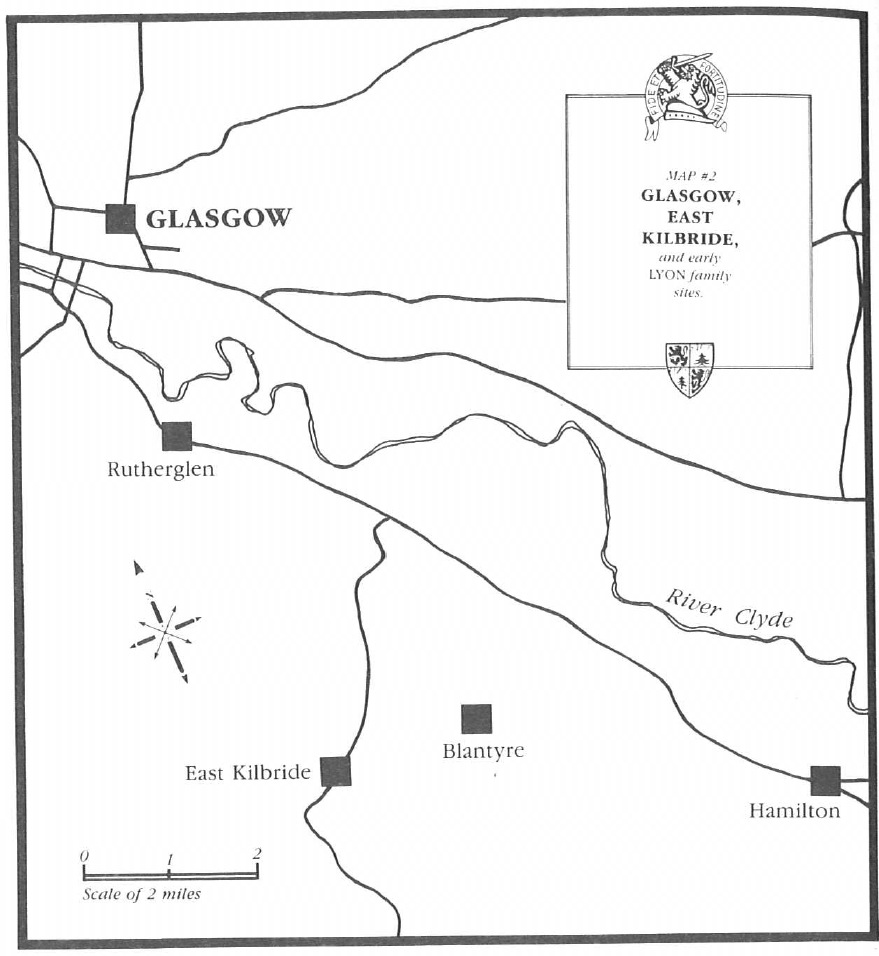

Sometime in the late sixteenth or early seventeenth century, a member of the Lyon clan moved southwesterly and settled near the farming villages of (East) Kilbride and Blantyre, eight miles southeast of Glasgow (see map 2). Similar to the early Lyons in the county of Angus, the given names of Thomas, John, and James predominate among the East Kilbride and Blantyre descendants. By the early eighteenth century, the family prospered through agriculture, sowing and harvesting oats in the marshy fields between East Kilbride and Blantyre.

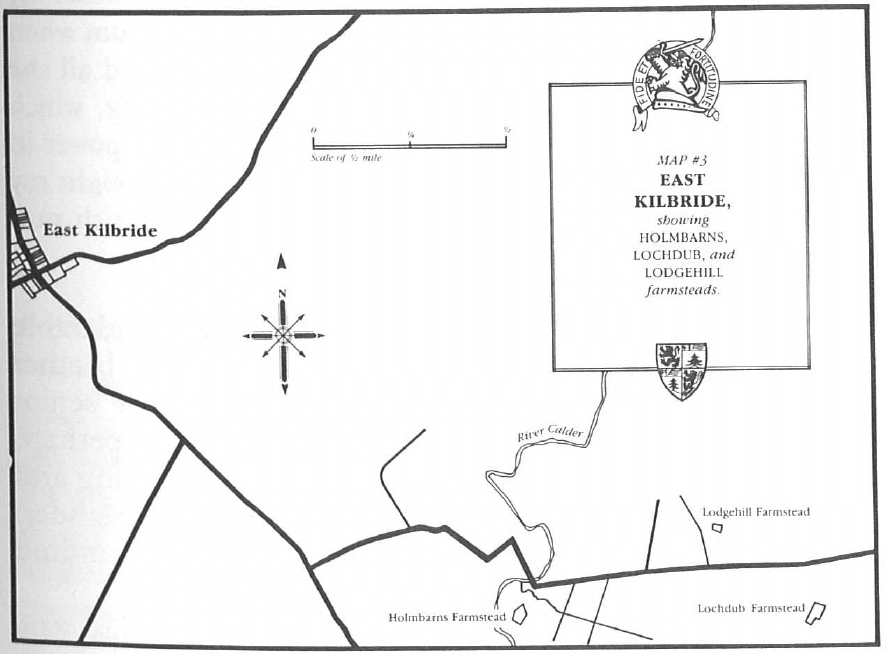

John Lyon (grandfather of the Mormon poet) was born on June 26, 1715. Though the family may have resided in the Blantyre Parish, the birth is recorded on the closer East Kilbride Parish Register. In 1747, John married Margaret Flemming. They had five children: Alexander, John, Margaret, Mary, and Thomas (father of the poet). In 1754, John leased a hundred acre farm from the estate of Torrance, known as Holmbarns (Holm Burn), located in Blantyre Parish. The land is located on a lazy bend on the east side of the River Calder. The lease agreement, apparently fulfilled, was for forty years. During this period John and his sons also farmed at nearby Lodgehill and Lochdub farms (see map 3). One son also extended his interests to a farming area known as Hairmyres in East Kilbride Parish; the family directed most of their commercial activity toward East Kilbride and not their “home” parish of Blantyre. Holmbarns was marshy land with many acres of trees as well as some arable sections. [2] In May of 1770, John Lyon was living at Holmbarns and voted against a new minister for Blantyre (Wright 35).

Records and personal recollections give only sketchy information on the senior John Lyon. His farms were sufficiently successful as to endow him with some wealth and status; he would have been known as a prosperous gentleman farmer in both Kilbride and Blantyre. East Kilbride Parish was a large area, ten miles long, varying from two to five miles in width. In the late 1700s, 2,359 persons in 587 families comprised the rural village and parish. The inhabitants supplied food and building wood to urbanized Glasgow (Statistical Account of Scotland 414). Grandfather John assuredly forayed frequently into the large town to sell goods from his prosperous farms. When John Lyon the elder died he left a large sum of money to his children, and Alexander was named executor of the estate. In a handwritten manuscript, Mormon John Lyon recalls:

My father [Thomas] would often comfort my mother by telling her that I would be sure to receive a goodly sum when his brother [Alexander] died, as he had not received all the legacy his father left him by seventy pounds sterling, which he [Alexander] kept from him in consequence of a power in the will, to give this sum to my father, when he thought my father was capable of putting it to a proper use, which sum he never received. [3]

Seventy pounds sterling would have been a considerable gift in 1800, but Alexander never considered his brother Thomas sufficiently mature to benefit from it. The senior John also leased a small farm for his son Thomas (perhaps Lochdub Farmstead), but the son knew little of farming and mismanaged it; the acreage reverted to the dutiful Alexander. According to Alexander, Thomas received several hundred pounds sterling upon his father’s death, all of which he allegedly squandered in fleeting business ventures.

The following diagram clarifies family relationships previously described:

[John Lyon & Margaret Flemming Pedigree Chart]

Thomas, father of the Mormon poet, was born at Holmbarns and grew up on this farm planting oats, milking cows, and tending cattle and goats. He went to the parish school. In the late eighteenth century, Scotland was probably the most literate country in the world, with free or very inexpensive education available in town or parish schools everywhere. Thomas attended school in Blantyre or Kilbride and gained fame “for being learned; he was known to outstrip [even] the parochial teacher in learning and science.” Thomas’s father and older brothers, “solid” farmers of the area, viewed his interest in anything but agriculture with disdain and even condemnation. His brother Alexander remembered that Thomas “was esteemed as a good moral gentleman, up to the time he was drawn into the militia” (ms). While in his thirties, Thomas volunteered to serve in a military unit his son recalled as the “Scott’s Royals, commanded by the King’s son, Duke of Kent” (the king was George III, of reknown in the American colonies). In the eyes of his older brothers, Thomas was merely running after fleeting glamour and avoiding his “obligation” to farm, but the affable, educated Scotsman was rapidly promoted and for a period of time became the Duke’s bodyguard and servant (so his son John recalled, having heard war stories by and about his father; perhaps some were a bit exaggerated). Edward Augustus (1767–1820), Duke of Kent, did indeed serve in the military and commanded troops in Gibraltar (1791 and 1802), in Canada (1791–94; 1796–1800), and in the West Indies (1794). George III viewed him as a minor filial embarrassment and kept him at a distance from the court. Records do not indicate that he commanded the “Scott’s Royals” (Dictionary of National Biography 19–20). If Thomas Lyon did in fact serve with the Duke of Kent, it was only for a brief period; young John never recalled his father mentioning Gibraltar, Canada, or the West Indies. Lyon family tradition avows that Thomas journeyed to India in the military; perhaps India and the West Indies could have been confused in the mind of John when he recalled his father’s stories. The Royal Highlanders (not the “Scott’s Royals”) served in the West Indies from 1795–98, and Thomas may have been in this unit with Edward Augustus in battles on Martinique and St. Lucia. A ceremonial sword, currently in the possession of a great, great grandson, John Eorsberg Lyon, is purported to have been used by Thomas in the Indies.

At some time and place in his military career, Thomas was named assistant to a surgeon in the Royal Commissioned General Inspectors. In this capacity he traveled throughout England, Ireland, and Scotland, inspecting military hospitals and perhaps assisting a surgeon on specialized medical problems.

In 1798 or 1799 Thomas met and married Janet McArthur, born in Pollokshaws, Renfrewshire, Scotland, in about 1777. Pollokshaws, sometimes known as Shaws, was a small settlement in Eastwood Parish, just three miles southwest of Glasgow. Janet and Thomas were probably married on one of his return visits to Scotland, while still in the military. Thomas would have been nearly forty years old when he married; Janet, twenty-two. No record of the marriage exists on parish registers in Glasgow, Kilbride, Blantyre, or Pollokshaws, nor are recorded the births of any of the four children that came to the marriage. Thomas, having “seen the world,” probably was somewhat estranged from the family religion, Scottish Presbyterianism, and felt no obligation to register the marriage.

How long Thomas actually carried out the duties of this military office is not known. At some point before his marriage, he became seriously ill with asthma and was sent home to try to regain his health. He never received a regular pension from the army, but after he married Janet he was sent to Chelsea, in South London, to recuperate in a military hospital. Little improved, he returned to Scotland at age forty-seven, weakened and asthmatic. His brothers viewed him as an unrepentant prodigal son. Instead of taking up residence in Kilbride or Blantyre, he moved the eight or ten miles to Glasgow, taking a job as a clerk in a brewery. Again, his poor health kept him from adequately filling the job, and he never worked again. In 1811 he died in Glasgow, at age fifty-three, most assuredly a victim of the debilitating effects of asthma.

Thomas was more of a dreamer than his father or brothers; he chose the romantic solution—leaving the farm to try fame and fortune in the world outside the small radius of East Kilbride, Blantyre, and Glasgow. Perhaps because he was the youngest son, his older siblings considered him the irresponsible, spoiled child. After Thomas’s death, some of his bar cronies in Kilbride recalled Thomas’s athletic prowess, “putting the stone [shotput], dancing, or running a race, or jumping, or drawing the badger.” They also recalled his intellectual abilities, confiding in young John that his father had not really been as irresponsible as Alexander would have everyone believe. John Lyon’s detailed recollection of his father’s funeral and related activities provides the best available insight into his father’s character and resulting family tensions:

My father died, and my mother was left in great poverty. A letter was sent to Kilbride of my father’s decease, and [Uncle Alexander] was informed that if he did not come to his funeral he would lie in state until he came. With this notice, he came with his son James, and brought with him a grand coffin and a hearse with an extra horse. Everything was done rapidly; a few of father’s friends dressed him and his body was put in the coffin. A great number of people who were acquainted with my father, some said to the number of four hundred, were congregated on the street to see him decently conveyed out of the city. And his only son, myself, riding behind the carriage on a country cart horse. A mile out of the city [Glasgow] my uncle stopped and thanked the people. When we drove on to Kilbride, half way to that place, we were met by a large company of farmers on horseback which formed quite a cavalcade. . . .

Never shall I forget the appearance of my uncle on that occasion; he had on a long-tailed dark blue colored coat, ornamented with large brass buttons and a scarlet vest with pockets on each side, down to his small clothes, his unmentionables hanging without braces [suspenders], showing his shirt all round, of homemade grey cloth buttoned at the knees, over a pair of dark grey rigging—for stockings, lost in a pair of hob-nailed shoes. . . . After my father was interred my uncle invited the whole regiment of cavalry into the head inns, where he sat at the head of the table, with the minister of the parish on his right hand and myself on his left. Shortbread and fancy biscuits were set on trays along each side, with here and there large flagons of wine, were in readiness to be emptied, by men who were appointed by the innkeeper for that purpose, for the company’s service, a motley company of aristocratic landholders. The reverend Gendeman asked a blessing and the noisy conversation began about my father, of what he had been and of what he would have been had he become a farmer. This farce continued for a long time, complementary to my grandfather and uncle. . . .

My uncle got up, when the company was pretty well inflamed from the spirit drawn from the flagons, and made a speech lamenting over the loss, and folly of my father; and also of my grandfather, in giving my father so much schooling, and neglecting his other two sons, with half the tuition lost upon him [Thomas]. What was all his activity in rural sports of jumping, racing, and drawing the badger, compared to virtuous, industrious economy? His father had given him a farm, but he knew nothing of sowing, or handling the spade, nor of the seasons, when to sow, or when to reap and in consequence had to give up the farm, which his father turned over to himself, whereon, he by industry and economy had made a good living and brought up his family respectably, and had saved something for a rainy day. It was true his father had left his misguided brother several hundred pounds sterling at his death, and being chosen as his executor for his two brothers and two sisters, he, with the counsel and consent of the family had given him at several times large sums to start him in business, but all failed in his thoughtless mismanagement. He doubtless had still kept in his hand a few pounds, by which he was able, to put him decently below the sod, as they all could testify, who formed this intelligent company. In rounding this infamous, shameful character of his brother, he put his hand into his britches pocket and drew out his purse, from which he extracted a silver dollar, held out the piece to me, saying in a loud tone, “There John I make you a present of this piece of money, hoping that you will be a more careful and thoughtful man than your father.” With that he put the dollar in my hand, with a flourish and wave of his hand, and sat down, looking at the company, as if he had done some great deed, expecting somebody to respond to the philanthropy of such a noble action. Boy as I was, only eight years old, I felt that I could have thrown the dollar in his face. I cried, however, and continued my lamentations, until my Aunt Mary took me to her home. [4](ms)

This account was written as many as seventy-five years after the event. Uncle Alexander, in retrospect, had likely become more villainous than he really deserved; yet from that young age, John was able to recall the opulent attire his uncle paraded before the mourners. The purpose of this description was that of demeaning Alexander, who more appropriately should have worn black. The story indicates that Thomas had many friends and acquaintances, both in Glasgow and Kilbride; he undoubtedly drank, played, and philosophized with many neighbors and relatives. Throughout the account there is a mild tone of sarcasm toward the entire group of characters and their irreverent words—’a motley company of aristocratic landholders,” “the reverend gentleman,” “this farce continued”—all indicate John’s contempt for the absurd performance and its saturated actors. Yet he does not hasten to defend or extol his father in this manuscript; in only two of his many personal recollections does he ever praise his father:

As a child I thought him a wonderful man in his knowledge of government, physic, and geographical research. This as a boy I drew from conversations and by the acquaintance of his friends . . . but in my advanced life I learned that he was greater in my estimation than even my wonder when I was a boy. (ms)

Most likely young Lyon simply did not know his father well since Thomas was often away in England or sick in bed. Judging by the absence of references to his father in his later prose and poetry, Thomas did not exert a major influence on the life of his son. John, however, was careful to try to reverse the prodigal image his uncles held of their venturesome brother. The death and burial of Thomas, like so many of the Lyon family in Kilbride and Glasgow, are nowhere recorded on parish records.

Even while Thomas was alive, Janet McArthur Lyon was likely the stronger, more constant of the marriage partners. With the death of her husband, the thirty-four-year-old widow took on the sole support of herself and her son, never getting any assistance from Alexander or the Lyon family estate. Janet had given birth to four children; the first two died in infancy, perhaps succumbing to smallpox or “consumption,” common fatal infant diseases of the day. [5] John was born in 1803; and the fourth child, Mary, a year or two later.

By 1803 Glasgow was a rapidly growing city, the largest in Scotland. The first official census in 1801 counted 77,385 residents; by 1811 it had grown to over 100,000, and by 1821 it had nearly doubled from the 1801 census, with a population of 147,043 (Boyle 10). The city comprised 1,864 acres, or approximately three square miles, with most of the town spread out along the north bank of the River Clyde (see map 4). The name Glasgow likely comes from a Celtic word meaning “dear, green place,” a truly representative name for the verdant Clyde Valley in which it is located. Glasgow is closer to the Arctic Circle than is Moscow, Russia, and was the northernmost city in the world to reach a population of one million. It was not only the largest city in Scotland but also one of the oldest, with continuous habitation from pre-Roman times. It likely owes its existence to the eighteen-inch shallows of the River Clyde which, before dredging in the 1800s, caused ships to anchor in the area.

The dramatic growth of Glasgow in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries was due to the tobacco and sugar trades, the increase in weaving, spinning of cotton, and dyeing, and the trade and commerce resulting from these industries. Children and adults from the Scottish Highlands migrated to the cities to find employment; Glasgow became the largest commercial center in the country. Half of its population worked at the looms or in related trades.

Thomas and Janet Lyon, originally from rural areas of nearby Kilbride, Blantyre, and Pollokshaws, took up residence in the busy city in hopes of better employment than small-town life provided. Yet Glasgow was hardly a haven of health and the good life. Turnips, carrots, herbs, and fresh fruit, recently introduced in rural areas, were expensive or unattainable in the cities; even kale, a standby of the common people, was hard to purchase in Glasgow. Potatoes and oatmeal, so readily available to village farmers, had to be purchased by city dwellers. Recent introduction of tea and sugar to Glasgow added variety to the diet but little nutritional benefit. In short, urban dwellers in the early 1800s suffered more health problems than their village cousins (Smout 250–51). Epidemics took a high toll among city dwellers, who often lived in dirty tenement slums. Smallpox was by far the worst killer; in 1800 a third of all infant deaths was attributable to the disease. Half the children born in Glasgow died before age five (Mackenzie 172). Inoculation against smallpox was known and used in the Highlands, but city folk generally distrusted the process. Glasgow in 1801 adopted a policy of free vaccination for poor children but found much suspicion and too few participants (Smout 256). John Lyon’s two older siblings died in early childhood, perhaps from rampant smallpox. It is not unlikely that saddened and concerned parents may have taken John, born in 1803, to one of the free clinics for vaccination.

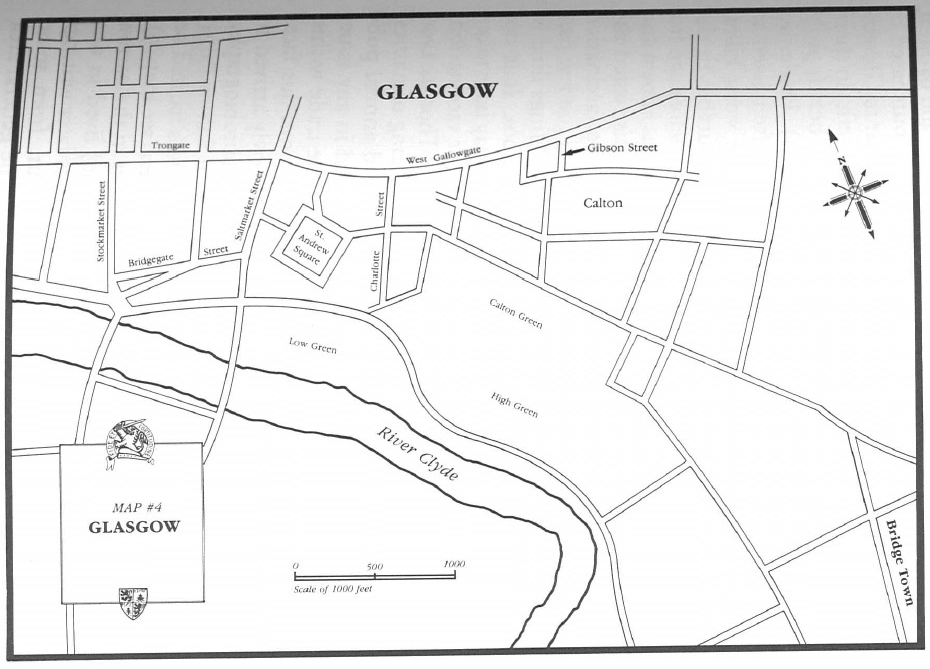

We do not know exactly where Janet and Thomas Lyon lived in Glasgow. The Glasgow Directory, a listing of names, addresses, and trade or profession, commenced annual publication in 1799, but Thomas is never included in any issue. Owning no property nor practicing any unique trade within the city, he and his wife would have been anonymous faces in a noisy city of thousands of poor workers newly arrived to feed the Industrial Revolution. In a single-page autobiography, John mentions that he was born “in Bridgetown Barony Parish of Glasgow” (Lyon, Biography). Bridge Town was located on the east end of Glasgow, beyond the High Green (see map 4). Several stone tenements were crowded together in the narrow streets, where at times “up to fifteen [people] lived in one house [one room flat]” (Mackenzie 171). In his later writings John never mentions a street or address but, from some unintentional clues in his sketches, locating the general area in which he and his parents resided is possible. In the story “A Tale of My Dry Nurse,” he mentions “The old Boar’s Head, an old, antiquated tavern opposite the barrack yard” (Lyon 139). A 1904 publication in Glasgow recalls that the Boar’s Head Inn was on the east side of Marshall Street, off Gallow-gate, and that the 71st Infantry Regiment, after the Battle of Waterloo (1815), would come over from the barracks and fight their battles all over again. Youngsters, when accompanying drinking parents, always got a free glass of milk because the landlady kept cows on Glasgow Green (“Round the Bars” 289–90). John also mentions the clay fields (143) on the outskirts of town, as well as Glasgow Green and Baalam’s Pass (148, 154). [6] In the story “The Self-Made Chemist,” from the same collection, he mentions the Tontine and Barrowfield’s Bar, also located in the extreme eastern section of town, near the Gallowgate area. Finally, an unpublished story, “Dr. Barnett,” describes meeting a childhood friend and going to their old gaming area, St. Andrew’s Square, not far from the previously mentioned areas. All these streets, bars, and Glasgow Green were located in a small radius on the eastern edge of Glasgow in 1803. John’s parents probably rented a small flat in the Bridge Town and Gallowgate areas, one of the oldest neighborhoods in the early 1800s.

Due to the rapid influx from rural areas, poor city planning, and booming business in cotton, linens, and weaving, Glasgow had the worst slums in all of Europe at the turn of the nineteenth century. The Lyons lived in these gray surroundings. In August 1803, William Wordsworth and his sister Dorothy visited the burgeoning town. She observed:

One thing must strike every stranger in his first walk through Glasgow—an appearance of business and bustle, but no coaches or gentlemen’s carriages. . . . I also could not but observe a want of cleanliness in the appearance of the lower orders of the people, and a dullness in the dress and outside of the whole mass. [7]

Given a choice, young John Lyon might have preferred birth and childhood in some other town; given the circumstances of his parents, Glasgow was home.

A local poet, John Mayne (1759–1836), praised Glasgow’s beauty and industry:

Hail, Glasgow! Fam’d for ilka [every] thing

That heart can wish or siller [money] bring;

Lang may thy canty [merry] musics ring,

Our sauls [souls] to chear;

And Plenty gar [makes] thy childer sing,

Frae [from] year to year.

. . . .

In ilka houfe, frae man to boy,

A hands in Glasgow find employ:

E’en maidens mild, wi’ meikle joy,

Flow’r Lawn and Gauze,

Or clip wi’ care the Silken-foy,

For Lady’s braws.

Look thro’ the town;—the houfes here

Like royal palaces appear!

A’ things the face o’ gladnefs wear,

. . . .

—O, Glasgow! may thy bairns ay nap

In smiling Plenty’s gowden lap;

And tho’ their daddies kifs the cap,

And bend the bicker,

On their auld pows may bleffings drap,

Ay thick and thicker. [8]

Unfortunately these blessings did not immediately distill on the heads of the Thomas Lyon family. Poverty, reproach from country cousins, and childhood illness and death aptly characterize existence of the Lyon family in Glasgow. City directories extol the rapidly growing commerce of the day, the monumental churches, the college, the hospitals, the Royal Infirmary, the lunatic asylum, and the scores of literary and benevolent societies. The Lyon family derived little benefit from these amenities. However, a hundred acre public park, the Glasgow Green, was near their home, providing open-air play for children and leisure for cooped-up adults.

Fine gravel walks surround it, which, in some parts, are overshadowed by lofty trees. . . . In fine weather this beautiful lawn is thronged by busy groups, in the pursuit of health, wisdom, or pleasure. . . . Many are seen playing at the games of cricket and golf. Numbers are employed in washing or drying clothes; and in summer the young resort to the contiguous river for bathing; in winter for skating, curling, etc. (Glasgow Delineated 77)

Young John Lyon knew the Green very well. In later years, he joyously recorded recollections of his childhood in the area:

Glasgow Green, during the summer months, is a beautifully decorated public ground along the borders of which, the river Clyde winds its majestic waters. Intersecting are finely graveled walks, shaded on each side with tall beech and elm trees, and beautified with a large monument erected to the memorable Nelson of Trafalgar notoriety. There are, also, beautifully enclosed mineral springs, known by the name of Aaron’s Wells; and, on the margin of the river stands a stately, solemn-looking building, called the Dead-house, where boats, creepers, baths, and other apparatus are always in readiness in case of accident, with attendants to look after the unfortunate. (Songs of a Pioneer 149–50)

On a folded, scribbled, half-page note, likely a rough draft of a letter to a friend in England, Lyon wrote from Utah: “Generally all well behaved men altho’ far from home retain a life-long-love for the land of their nativity, yeah’ even for the poorest moss-grown district, and the meanest portion of household tenements.” He indeed grew up in a poor, damp, degenerate tenement area, but as a very young child, he played obliviously on the Green and rejoiced in life.

In a dingy, multiple-storied building with red sandstone walls eighteen inches thick, the Lyon family shared a small flat. Thomas may have worked irregularly, bringing home a small income to the family of four, but only for short periods. He received no pension support from the military; his work as clerk in a brewery lasted only a brief time. Janet, the industrious mother, capitalized on the growing weaving business in Glasgow and rented or purchased a hand loom which occupied center stage in the room. She contracted work for capital-minded businessmen and enlisted her son, as early as age four, to assist in the labor.

A small child became an especially valuable worker since the child could crawl underneath or behind the large looms, passing the heddles back to the main weaver. This and other such chores contributed to a rapid decline of children enrolled in school; they were more valuable to parents and family as “heddle-boys,” millworkers, or workers at a score of other tasks, than as educated members of society. Glasgow, swelling with the Industrial Revolution, experienced a dramatic increase in illiteracy and its resultant social woes. Large factories employed hundreds of cheap-labor children, who were just the right size to crouch and work behind the looms or in mine tunnels. Some industries, or towns, such as New Lanark, established disciplined schooling as part of the work regimen. John was one of the many boys, usually from the poorer sections of town, who attended almost no school. Perhaps Thomas and Janet could not afford the few pence a year for school fees; more likely they simply needed his hands at home. Ailing Thomas, however, found sufficient leisure to teach his son the alphabet and get him started forming letters and words. John remembered frequently taking pieces of chalk and scribbling letters on shutters, doors, walls, or any flat surface. Litttle by little he learned some rudiments of writing. He recalled:

My mother however could write a little, and as she had to send to her employer for thread, and sometimes money, these notes she would read to me. . . . I read them the best I could on the road going, and in this way could see how the words were formed. (ms)

Life for the weaver’s son was not all dull work, however. In the summers he waded in the Clyde at the well-known Broomielaw, where the river was no more than eighteen to twenty-four inches deep. In winters the ice provided an arena for games and sliding. Glasgow Green and St. Andrew’s Square were open spaces for group games: “tig, tow and touch wood,” “smugglers and gaugers,” “I spy,” “Tumble the wulcat,” “Scotch and English,” “Wully, Wully Wastle, I’m upon your castle,” marbles, and many other of the running, chasing, skipping, and hiding games which flourish in poor areas (Cochrane 33). When he was a bit older, he may have played cricket, or even a rough form of golf, sharing the Green with scores of cows and the resultant mess they leave. Time spent in childhood games provided a necessary break from the otherwise dreary, closed-door existence of tenement Glasgow.

At an early age, John Lyon developed a lasting fear of ghosts and spectres. The family tenement room was only a few blocks from the Blackfriar’s Church in High Street. Parents would have warned and even forbidden him from visiting the shadowy area; he went anyway. This undoubtedly contributed to his dread of the dark and the fear of apparitions. Three of his stories recount ghostly experiences from his youth. In “Murder Will Out—A Strange but a True Story,” Lyon relives what he describes as “one of my earliest recollections.’ ‘ When he was about five years old (1808), a public hanging took place in Glasgow, at the Tolbooth, Glasgow Cross, not far from his home. His parents had known the accused, named Mr. Gilchrist in the story, and actually hired a second-story room from which to observe the execution; their son accompanied them. He does not recall or even describe the hanged man but “in after years the view of the scaffold never left my mind.” A different story, with the same title (“Murder Will Out”) appears in Songs of a Pioneer. Lyon wrote:

When I was nine years old I was terrified to go to bed alone; I had heard so many tales of ghosts and witches that I was afraid . . . to sleep alone. My mother was a strong-minded woman on every subject but one, and that was in the fear of spirits after death, and of their appearance to people who survived their decease. In consequence, this subject was often brought up by neighbors who came to visit her, and I became a retentive auditor and stored my mind with these spiritual relations that to this day cause me to keep a sharp lookout, in out-of-the-way places, for something supernatural. (Songs of a Pioneer 258)

The nearby cemetery, the hanging, the fears of his mother and her friends, the somber neighborhood and its old buildings and unlighted streets, the child’s natural desire to slightly scare himself—all combined to create in John a lifelong fear of darkness and ghosts.

Little John’s most exciting days were spent with cousins and other relatives in the East Kilbride and Blantyre areas. On holidays, or for his father’s health, or when food was scarce in Glasgow, the family journeyed the eight or ten miles to the old family homesteads. Leaving the gray or faded red-rock, smokey city for the green countryside must have thrilled the young lad, too long cooped up in the tenement and already working to assist family finances. The Lyons usually walked the several miles, perhaps hitched a ride on a friendly farmer’s wagon, or may have occasionally paid a few pence to ride one of the regular coaches which offered public transport. While Thomas may not have relished the visit to his censorious brothers and sisters, Johnny found exquisite delight in the freedom of rural life. He played in the streams, fished, lazed in heather, and counted passing clouds while lying on his back in the mossy green meadows.

Uncle Alexander occupied a large house atop a rising ridge, or brae, known by all as Lodge Hill, in Blantyre Parish.

It consisted of a barn, then the dwelling house, a stable, byre (or cow barn), and cart house, all in one straight line. The dung pile lay opposite, forming a hill as conspicuous as the house itself. The interior of the house was as much a curiousity as the outside. The door in the centre led between two rooms, the one on the right was twenty feet long, having two windows facing north and south. The one on the left was narrow and here were kept all their chests and all that was by them thought valuable, a table and a small looking[glass] and a picture or two on the wall. The room on the right hand side was called the kitchen which had better answered the cognomen of hall. As you entered this between two box beds, there was before you a large fire place, raised about a foot high on each side, with large unhewn rocks, and a division in the centre to hold ashes. From the roof hung a large chain, to which was attached a boiler or pot called the chaff, or cowl pot. On the front of this fire grate a bar of iron ran from side to side to hold the candle, or light which illuminated the room during the evening. Beyond the fire a door entered into the stable, byre and hen house, which was very convenient in winter when snow and rain, and wind storms came blowing a hurricane over the hill farm, altho’ perhaps the smell of the dung pit was not so pleasant, but usage is everything, and fresh air is not appreciated when colds and fevers are the consequences, particularly in a place where wind was blowing continually from all points of the compass. . . .

In the cart and tool house (as it was called) which occupied nearly half the row, was the hen house which in the morning there was such a noise of crowing kept up, that would have wakened half the parish, had not their banks been half a mile higher than the villagers in Maxwelltown, Haremires, or Lochdubbs. There also lay the ploughs, harrows, spades, shovels, all as snug and dry as when laid fast, well washed and clean to keep them from rust during the winter. . . .

[In the house] brooms, and scrubbing brushes were all made of heather, and the churns, and milk dishes were all purchased from a country cooper, all made according to the old style. In fact all the dishes for domestic use were made out of wood or horn, and the food of the same quality, day in and day out, the year round. In the morning a large wooden bowl was filled with oatmeal porridge, and each one had what was called a coggie [bowl] when they took from this large bowl, into this coggie what porridge and milk they intended to eat. Then cheese and oatmeal cakes, or sometimes potatoes and beef or mutton and/

To young John the home was a mansion, albeit the eccentricity of its owner, who insisted on everything being homemade and done in the “old style,” and who abhorred tobacco and chocolate. The smell of the dung pile hung in John’s nostrils and memory, quite logically for a city boy visiting the country; the noise from the henhouse also stayed in his mind, a sound not so frequent in busy Glasgow. But perhaps most memorable were the meals, bounteous, varied, with occasional sweets, fruit, meat, and cheese, even for breakfast. The slender boy from the hungry city anticipated and relished the visits to East Kilbride. Even after his father’s death, John continued his visits to Lodge Hill.

While there, Uncle Alexander sent me to herd the cows; he often found me roaming amongst the heather looking for birds’ nests. He was highly displeased and sent me home the next day, saying that the cattle were better fitted to herd me. . . . Although losing his approbation as a herd boy, I still had his favor when I went to see him at other times, when he set me to cleaning the byre or cow shed, for labor was a virtue greater than any other pursuit to him. (ms)

As executor of the estate of his father, and well-to-do farmer, Alexander occasionally filled the role of surrogate father to young John.

Thomas’s sister Margaret married Andrew Scott, who owned a large cooperage (for barrel-making and repairing) in East Kilbride. The couple had several children, all of whom died, apparently of consumption or measles. When John was five or six, his Aunt Margaret made arrangements with Thomas and Janet to adopt John as their own son. The adoption appears to have been a charitable act, to help out the poorer city dwellers in their economic plight; perhaps they had “taken a shine” to the sensitive child. John left Glasgow immediately and took up residence with his aunt and uncle. He helped in the prosperous cooperage, which had most of the business in the area. Life now promised much more security and economic hope for the future; yet within a year Andrew Scott fell sick with an inflammation of the lungs and died in a few short weeks. John continued living with his widowed Aunt Margaret but often wandered off to fish for minnows or to creep in the graveyard to deface the tombstones or to fight with his little comrades or to call ‘them nicknames, which was a grave offense.” He often sneaked away from his grieving Aunt Margaret to visit his Aunt Mary, a spinster who lived on the other side of the village. With no children of her own, she doted over Johnny and even encouraged his frequent and lengthy visits. A rivalry developed between the two sisters and Mary assumed the caretaker role of the adventuresome child. But she, too, soon tired of his boyish exuberance and childhood antics and finally, in late 1809, returned him to his parents in Glasgow.

The return was not pleasant for the six-year-old boy, already reared in one household, transplanted to another, shifted to a maiden aunt, and finally sent back to the starting point of the game. His parents were saddened that he now would not have the large inheritance they had expected from Margaret and Andrew. Further, John’s sister Mary, four or five years old, was seriously ill with measles, and despite the proximity of the prestigious and charitable Royal Infirmary, she died shortly thereafter. Lyon never mentions a funeral, but in adult life recalled his sister in a fine poem, “My Sister, Charity”:

What a world of thought gleamed from her blue eyes!

So chequered and spangled with glowing light,

Like the gold-tinged clouds of a thousand dyes

That peopled a scene of visions bright.

. . . .

Her infant innocence gladdened the heart,

That love from the well of affection drew,

But those hopeful tears had a burning smart,

In the mother’s eyes, when she sighed adieu.

(Songs of a Pioneer 27)

Glasgow parish archives do not record the date of this sad death; Lyon poignantly observed that “this left me sole heir to my father’s poverty” (ms). Three of the four children born to Thomas and Janet died very young; Mary’s death was the most tragic since she made it past the crucial and vulnerable first year, only to succumb to what, in the twentieth century, appears to be a minor childhood disease. Little Mary was probably buried in a common grave at public expense.

Thomas’s amiable personality and Janet’s work brought numerous friends to the tenement flat. Mrs. Gilchrist, wife of the hanged man already mentioned, was an old friend of Janet and frequently dropped by. Former friends from army days came to see Thomas and exchange stories. He had many friends from his brief work in the brewery, and they likely drank together in one of the more than 700 public houses that served spirits to the town’s residents. Drunkenness was rampant in the city. An 1840 statistic indicates that “spirit” consumption in England averaged seven pints per person per year, thirteen in Ireland, and twenty-three in Scotland! (Glover 321). “Glasgow Punch,” a drink made from West Indian rum diluted with three parts water and flavored with sugar and lime or lemon juice, was even more popular than Scotch whiskey (Cochrane 33–34). Thomas was well known and liked not only among drinking friends but also among neighbors for his ability to teach, converse, and debate. His acute asthma and an accident at the brewery left him unable to work. After the death of Mary, he spent more time teaching his son to read and write, using the basic primer, the “Big Spell.” He also encouraged John to draw pictures of the world around him.

Thomas died in 1811, likely in the early spring, victim of prolonged asthmatic debilitation. As already indicated, Alexander paid the funeral expenses. Thomas was buried in a small, now unknown cemetery plot in East Kilbride or Blantyre. His funeral service corresponded to the customs of the day. “A funeral was an entirely male occasion; the service took place in the house, and there was no service at the grave” (Haldane 41); it was an occasion for the reunion of friends and relatives, and it took a rather festive character. Janet said her tearful goodbyes in Glasgow; eight-year-old John had to experience the “mockery of a funeral” with all his male relatives. The drinking and demeaning of his father troubled him for the rest of his life. One tragicomic incident related to the funeral stayed with the fatherless son. His uncle brought an extra horse, albeit a large cart horse, to Glasgow so young John could travel in style to East Kilbride.

By the time we got to Kilbride my poor thighs were shaved so bad that when taken off the horse I cried with pain. All the village turned out in the graveyard, and I heard an old woman bemoaning my situation, saying, “Poor boy, see how greaved [sic] he is in the loss of his father”; but she did not know how sore my legs were, in being cramped and skinned on a long ride, never having been on a horse in my life before, (ms)

John stayed with his aunt in East Kilbride for a week and then returned to the tragedy of a disintegrating home. While John was at the funeral, “the owner of the house where we lived had all we possessed put in arrest, for rent until a roup, or public sale could be had.” Janet was able to spirit away her loom and some weaving tools, but John was caught trying to “steal” a black leather bag, his father’s most prized remembrance, filled with surgical lances, saws, and knives used while he served in military hospitals. One can imagine the deep emotions for young Johnny upon losing his father, the degree of humiliation in having to submit to his uncle’s braggadocio and disdain after the funeral, and then the ultimate degradation of losing the flat and the one possession that mythically tied him to his father’s past. The laird had legal right to place such a hold on the property—debts had mounted and rent had not been paid. The legality, however, did not ease the pain.

“My mother removed to another house [flat] where she followed her employment, without a bed, chair, or seat, until she bought a few articles of furniture” (ms). Her son of course accompanied her to the new dwelling, living a life of simple subsistence. The tenement building was likely in the same older section of Glasgow, the east side, near the Green.

Not only was Janet able to buy some used furniture but also she was able to send her son to school for the first time in his life. He was now eight years old, two or three years older than the usual starting age, but certainly not the only “older” boy in the beginning class. He already knew the alphabet and must have been able to read some basic words. The school he attended is lost in anonymity, but the master was “one of the most severe who ever handled cane or ruler.” The cane was for punishment, and Johnny likely needed it on more than one occasion. With the head start gained at home he progressed quickly, not through structured grades but through graded readers, where, after a year, he had mastered Scott’s Lessons, the highest reading text in that rigid school. He spent another four or five months in a second school where he began preparation “to be a teacher of the A.B.C. Class” but for unexplained reasons never completed the training. This year and a half was all the formal schooling he ever completed in his childhood. At home his mother had him read to her from the Book of Psalms as she worked at the loom; she also required him to memorize passages from the New Testament, “which was a sore trial to me. However, since that time I can look back, to what I considered a punishment, to be one of the greatest blessings” (ms).

John and his mother, on a scant few occasions, ventured back to East Kilbride and Blantyre, where they ate better, breathed fresher air, and despite past animosities and judgments, were now well received. On one trip, John, nine at the time, learned of a fortuitous event that would lift him and his mother from poverty and grant economic security to the struggling boy. While in East Kilbride, he was called to the office of Hugh Tweeddale, a prominent lawyer in town; Tweeddale [maybe a created name] was married to Lyon’s cousin and hence was considered “family.” The lawyer informed the young lad of a romantic tale filled with intrigue and suspense, an immense inheritance that he could share, if he did not reveal it to anyone, even his mother. He agreed. And Tweeddale told him a fantastic story that in the previous century his grandfather’s two brothers each had a son; the sons got together and formed a contraband business in liquors and silks, smuggling from the West Highlands, to Galloway and Ayrshire, and back again. When caught they “volunteered” to leave Scotland and took up residence in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in British North America. There they again prospered, using the same skills and enterprises as before. They purchased a large tract of land and enjoyed the benefits of their labors. Neither married, but upon the death of the second, an illegitimate son appeared and claimed their household goods but could lay no claim to the amassed fortune due to his illegitimacy. In about 1800 he journeyed to Scotland to try to find the “legitimate” heirs of a rather illegitimately gotten fortune. He came to East Kilbride, inquiring for the Lyon family and was directed to Lodgehill. Alexander had listened to his story, including his desire to have part of the large legacy despite his veiled ties with the family, and an agreement was reached. Tweeddale was then hired to recover the inheritance money, some £30,000, now held by the Court of Chancery in London. All this was begun ten or twelve years before John heard the story and the case was still not decided. He was to receive £7,000 sterling, his uncles, Alexander and John, the same, and the illegitimate son a similar amount. Lyon, as his father’s only living heir, recalled that “when I was told that I would have 7000 pounds for my share, I hardly knew whether I carried the earth or the earth me.” Such an immense amount was not fully comprehensible to the boy, but he obviously knew that it meant status, ease, better living. The matter was nearly decided, and all Tweeddale needed was Lyon’s power of attorney and a promise to not relate the incident to anyone. The boy signed and promised, as did his uncles, and the lawyer prepared affidavits and letters for London. If he indeed did keep the secret from his mother, he would have shown great restraint, for their living conditions were falling, with no hope for betterment. As a young schoolboy, he must have floated elatedly from classes, to home, to play on the Green. He would now be rich!

Before the lawyer could depart for London, a Mr. Russell, a teacher in Glasgow, visited Tweeddale, informing him that he was married to a young woman by the name of Lyon, whose mother was a full cousin to the deceased and hence more closely tied than the Kilbride Lyons, who were only half-cousins by a second marriage. Russell employed lawyers; Alexander begrudgingly paid more to Tweeddale, and the case dragged on. During the time when prosperity seemed imminent, Alexander sported his memorable long-tailed, light blue coat, red vest, and knee breeches; but when “Mr. Russell laid in his claim, he [characteristically] cast them off, declaring that all the beggars in the country . . . claimed his relationship” (ms). Now, after a decade-long battle in London, the hassle was to begin again. Alexander paid even more for legal fees, but finally gave up; the issue was never fully resolved. Russell also wearied of dead-end legal fees and stopped his litigation in the 1820s. As late as 1870, Lyon recalled seeing notices that both the property and the fortune were still administered by the Court of Chancery, awaiting a certified heir. By 1870 he obviously was resigned to never receiving any money, but throughout many boyhood years he undoubtedly nurtured the hidden hope, the romantic dream, that a huge, future-assuring sum would descend upon him and save him from his gray poverty. It never came.

The basic needs of the small family demanded work now. Learning to read and write would produce no income, and Janet felt the need to help her sandy-haired son find a paying trade. She herself was able to get by now—two fewer mouths to feed, no major debts to repay. She grieved deeply at the loss of husband and daughter but determinedly set about to make a new life on her own. In late 1812 when John was still nine years old, his mother bound him as an apprentice to an established weaver, for a seven-year, on-the-job training program. A formal contract was signed; Janet received a few pounds sterling, and her son began what would be his work for the next forty years. The apprenticeship agreement was somewhat informal, made with one of the many free-lance hand weavers of industrious Glasgow. Lyon began his indentured work, twelve or thirteen hours in each long day, six days a week, seventy or more hours a week, and very few holidays. Sundays he had free to spend with his mother or in church, but if he took New Year and August Fair off, he might have to make up the hours.

From 1780 to 1810, weaving was a fast-growing enterprise throughout most of Scotland, an era that is commonly referred to as the “Golden Age” of the trade. Villages grew up around weaving mills; cottage industry in small towns prospered as families lessened farming activities, purchased a loom or two, and began lucrative family enterprises. The larger towns, especially Glasgow, flourished in the boom of new-felt wealth and opportunity. Weavers formed Friendly Societies and Savings Banks against a future day of adversity. Cotton, much of it from the new American Republic, flowed into towns along the Clyde for final transformation into shawls, linens, dresses, bonnets, lace. In spite of the invention and use of some power-looms, weaving was still very labor-intensive; handlooms outnumbered the costly machinery 50,000 to 2,000 in 1820. The cloth finishing work spawned a boom in bleaching, dyeing and printing of fabrics, and methods learned in cotton weaving proved workable with the fibers of flax and wool (Smout 237).

In the 1780s and as recently as 1805, the weavers were the most confident and affluent of all trade groups in the country. Village weavers usually had a large loom right in their home, planted a large family garden, and kept a cow or two for milk, butter, and cheese. Weavers in Glasgow gave up the agricultural delights of rural folk, but nevertheless prospered at the loom. Recalling the olden days, one weaver noted, “Four days did the weaver work, for then four days was a week . . . and such a week to a skilled workman brought forty shillings. Sunday, Monday and Tuesday were of course jubilee” (Thorn 9). While the account may be a bit exaggerated in favor of past leisure, it nevertheless demonstrates the relaxed, happy, prosperous life of a weaver in late eighteenth-century Great Britain. Weavers formed clubs for curling, playing golf, and fishing, and they created literary, debating, and political societies. Poetry was an especially vital auxiliary activity for many websters. Paisley, weaving center of the famous shawl, excelled not only in cloth but in verse—’it was a common saying at that time in Paisley, that every third man you met was a poet” (Blair 50). A good trade, a good life.

But the very year Lyon entered his apprenticeship, 1812, became the economic turning point for the Scottish weaver. Strikes, food riots, and attacks on looms took place in parts of Scotland and England, especially in Lancashire (Bythell 208–09), but none more devastating to the worker than the one in Glasgow. A thirty-eight to forty-six-hour workweek in 1790 earned a good weaver thirty-five to forty shillings. In 1812, he only earned seven or eight shillings for a week that might drag on for eighty tiring hours (Daiches 102). Instead of cutting back, he increased time and production in a necessary struggle merely to bring in enough money to survive. Each new apprentice added a few more pence to his marketable output; each hour of labor a few more inches of completed web. Wages and earnings continued to fall; in 1816 a group of protesting weavers was arrested in Glasgow and given “transportation”; that is, they were banished to Botany Bay, Australia. The Battle of Waterloo (1815) and the end of the wars in France brought thousands of out-of-work soldiers into Glasgow; many entered into a business they recalled as leisurely and remunerative—weaving. By 1819, a weaver’s wage in Glasgow dropped to two or three shillings a week. The industry never again rebounded. Using 1815 as base 100 percent, Bythell has shown that eleven years later woven calico brought only 33 percent of 1815 prices, yet the price of oatmeal increased to 107 percent of base. The increasing number of militant, angered, and anguished weavers concerned the local government. Websters (weavers, those who worked with the web of the loom) carried out another strike on April Fool’s Day, 1820, marching through the streets of Glasgow and scaring the populace; three men were arrested for “treason” and later hanged and beheaded. Life did not improve during the 1820s, 1830s, and 1840s for the struggling Glaswegian weaver (Bythell 279). Continued poverty, disease, hunger, and poor education were often the results. By 1850, mechanical weaving administered the coup de grace to most families trying to subsist solely on the thin fruits of handloom weaving.

Two important factors contributed to the decline of prosperity in Scotland’s weaving. Thousands of immigrants from the Highlands and from crowded Ireland congregated in Glasgow and other Scottish towns, producing an oversupply of cheap labor. Handloom weaving is relatively easy to learn; within two or three months an adult could turn out quality work and, at least in 1800, make as much as a master mason. The industry attracted thousands of previously unskilled workers, who soon flooded the market and quickly depressed prices. The second factor was the drawn-out Napoleonic Wars with France, resulting in inflation that increased prices on most goods, especially foodstuffs, but not woven materials. With rising prices for edibles, but depressed prices for labor, the webster suffered greatly. Two petitions to Parliament (1803, 1809–11) asking for a set minimum wage received little attention, and in 1811 Glasgow took the lead by establishing a union of weavers to bring about improved conditions. The union tried to restrict entry, standardize apprenticeship requirements, and fix a minimum wage. The next year, recognizing that courts were not upholding their demands and the few legal rights the workers had, the union leaders called for a strike. Most weavers in Glasgow responded, and for nine weeks in late 1812 and early 1813 the town reveled in a near-carnival appearance; little violence resulted, perhaps more drinking and tension-releasing than previously, as the weavers were happy at the prospect of finally doing something about their economic future. Quite unexpectedly, the union committee was arrested and its leaders were tried before the High Court of Justiciary, accused of conspiracy, quickly found guilty, and sentenced to prison terms from four to eighteen months (Smout 398). The severity of the sentences broke the strength of the union organization, and it gradually faded in influence.

Lyon’s master ran a small shop, employing a few other boys besides Johnny. Lyon probably began as a draw-boy, responding to the needs of an older, master weaver, drawing the shuttle through the warp. On Saturday afternoons he cleaned the loom heads, mended harness bridles, washed the brushes, and assisted in the set up of new warping boards for Monday’s never-changing schedule. For a young boy who had previously enjoyed being in the open fields of Kilbride, fishing, and giving animal shapes to passing clouds, the apprenticeship could only have been monotonous tedium. He struck friendships with the other boys. At first, as “new boy,” he would have suffered their cruel teasing and pranks. Later on he would have joked back, laughed, and spent his little leisure time with them, playing tops (made from broken shuttles) or a type of ball game using wool or cotton balls left over from their work. The boys may have gone to some of the inexpensive public amusements, shows and booths in Glasgow of 1812 to 1815. Johnny was rarely home now and, for such a young lad, felt an exhilarating independence. Work, friends, and the future occupied his first priorities. After a few wearisome months as a draw-boy, he began working as junior weaver, now able to put aside some of the irksome tasks required of the younger boys, but he was still closely supervised by other senior weavers.

The small shop was near the tenement building. The shop had a trodden earth floor, probably dug down below ground level, poor ventilation, and a moist, unpleasant atmosphere. It was alleged that the wood used for the loom was often “green with the damp.” [9] The materials used by the websters frequently reeked with a fetid gas. The work was rapid and at times taxing, filling the already-foul air with heavy perspiration smells—hardly the atmosphere for a boisterous, free youth. In 1812 (just at the time Lyon began to work as an apprentice) many contemporary writers and doctors noted the poor health of websters and their apprentices: “long hours in such damp and airless situations will gradually reduce and ultimately destroy the best constitutions” (Glasgow Herald, November 9, 1812).

For two-and-a-half years, from 1812 through 1814, young Lyon worked the weaver’s long hours, much of the time as an assistant weaver, setting up the loom and doing some of the actual weaving. But he was not the oldest in the shop and so continued the clean-up chores of early apprenticeship. He assuredly kept hoping, even expecting the £7,000 inheritance, £7,000 with which to acquire fancy trousers, elegant food, and a nicer living accommodation. But instead, he took home a shilling or two every two weeks; fortunately, he took tea (dinner) at the shop. On Sundays, he memorized scripture with his mother and may have gone to the Presbyterian church. But he also played along the Broomilaw by the Clyde and saw the large ships farther down the river. He dreamed of other places, opportunities, travel.

On a Saturday afternoon, when he was ten or eleven, he asked one of the older apprentice boys to go with him downriver several miles to see the big cargo ships. [10] Lyon may have even had the idea of running away to sea as a cabin boy. Although he considered himself a bit weak or frail, he was tall for his age and hence could pass for a thirteen- or fourteen-year-old. The next morning, “when mother had gone out dressed [in her best, perhaps to go to church], I laid up a good store of bread and cheese, and having put on my best suit of clothing I started with my companion for Greenock . . . Greenock, where the river Clyde was seven or eight miles wide, and . . . the great ships lying at that sea port.” To avoid detection by friends in Glasgow, he and his older companion left the public highway and crossed to the south bank of the Clyde, jauntily, eagerly, and naively walking the fifteen miles to Greenock. When he recorded this mischievous incident many years later, Lyon gave it the title “Strolling from Home . . . ,” because it began as little more than a casual Sunday nature walk. About midday, the two carefree runaways came to the point where the Cart River joins the Clyde, near the Inchinon Bridge. Never imagining that there would be a penny charge to cross the footbridge, and of course having no money at all, they were obliged to walk to Paisley, three miles distant, to avoid the charge. Willingly, almost joyously, in freedom from mother and work, the two made the six-mile round-trip but found themselves weary and hungry again. At this point they had already walked fourteen or fifteen miles, yet were still far from their romantic goal at Greenock. They made up a heartrending tale that they were brothers working in Glasgow and were on the road to Greenock to visit their mother who was violently sick. A kind farmer took them in and fed them a supper of broth and potatoes.

And then he made us a bed in the stable with some straw and two or three coarse sacks to cover us.

I never felt so uncomfortable in my life. During the whole night the horses kept chomping and neighing and knocking their feet against a large stone which divided our sleeping place from their crib. In the morning, we got up early and left without breakfast. When we got onto the highway, I had a great inclination to go home; indeed, through the whole night I had slept little and wept silent tears of grief, and thought often of the base lies my comrade had told the old man about our mother being sick. . . . My mother, oh! how I thought of her, how sad. I thought I saw her running everywhere, inquiring for me and crying in distraction, lest I might have fallen into the Clyde and was drowned.

Thoughts of his mother continued to torment John, but not enough to cause an immediate return. Nor did the absence from an apprenticeship bother him. The boys continued on, begging money from an old spectacle-maker on the road but going all day Monday with no food and getting both tricked and jinxed by an old man. By evening they were still closer to Paisley than to Greenock, hungry, repentant. Lyon remembered that a woman who used to make [weaving] heddles with his mother now lived in Paisley. He looked her up, told her their sad but humorous adventures, and after gentle chastisement, ate a hearty meal and slept in a fine box bed. In the morning the gentle lady gave him six pence to buy bread while on the way home, but once again his older companion convinced him that “if I returned I would get a dreadful thrashing, and that my master would perhaps put me in prison for running away” On to Greenock. A terrible rainstorm fell, dampening the idyllic vision of the sailing ships in port, and soaking the homeless waifs. And a wet lad once again quite naturally yearned for home, “I . . . felt downcast and sorrow, so vexed that I cried.” But as soon as the storm cleared, on they journeyed to the docks, looking for employment as cabin boys. By evening of this third day from home, hunger once again caught up with them; they ate bread and biscuits from the bakery; they slept that night in a fine coach parked at an inn.

Wednesday was spent searching for a ship to work on, but no captain would take the runaways for fear of punishment. They slept that night on the damp steps of a large house. Thursday—no luck with the ships—they spent the night in the police station. John’s companion fell in with a press gang, willingly went aboard a ship, and was never more known to his runaway companion. Friday, the sixth night away from home, John was taken in by a kindly couple who fed and warmed him. On Saturday, very much alone, he walked the fifteen weary, wet miles toward home.

It was sometime after dark when I reached the brigend opposite the jail, on the other side of the Clyde. An aunt, a sister to mother, lived in this place, so I went to her house. She was quite glad to see me, and said my mother had left not an hour before, and was almost distracted [crazy with grief] about me, and that I had done her a great injury and was a very foolish, wicked boy. . . . [She] took me home. When my mother heard my voice she ran and clasped me in her arms, and was frantic with joy.

It could be no surprise that Janet was overcome with joy; she had already lost her husband and three of her four children. Her eleven-year-old son had been gone for a week, obviously a week of frantic searching and anguished suffering for the young mother. Lyon never recorded his mother’s response, but his frequent thoughts of her throughout the week-long escapade indicate a mutual love that bound them. That he could have been gone for a whole week at such a callow age seems incredible. John did not record any punishment from his master weaver but did recall that his mother stood to forfeit the £10 sterling she had received when he began the apprenticeship. He was very likely penalized or in some form made to pay for his tomfoolery. Without a doubt, he learned deep appreciation for home and mother.

John went back to work, but the financial picture only worsened each year. He did not fully understand the economics of the moment, but he must have understood that he was not eating well; that his already worn clothes were too small for his slender, growing body; and that there was scant money for new items. His mother continued her solo work with a set of shafts and heddles, making lace now, as well as making heddles for others. But this type of piecework done for an outside employer also declined in value.

In 1815, shortly after John celebrated or at least observed his twelfth birthday, his shopmaster gave up the trade and granted all his apprentices their unconditional liberty. Lyon was assuredly disappointed that he would not be able to become a master weaver but recognized the worsening economic conditions. He now spent more of his time at home, helping his mother in her work, enjoying a short-lived childish freedom previously lost in a sweaty weaver’s shop. At twelve he was unemployed, unschooled, and unable to help with family finances. But he was not unwilling to work. After a few anxious months at home he made a decision

to learn the cotton-spinning business which was then high in repute as a money-making business. I then was engaged as a piecer, and although too old, and too large to lie below the carriages to run over me, I had to work almost for nothing, having sometimes given to me as pay, and with a grudge, four shillings for two weeks. In this way I felt bad, and my mother advised me to leave, but the wages of a [master] spinner having so high pay, I continued. And in the course of a few months I was raised to six, and ultimately to ten shillings fortnightly. (ms)

At twelve, Lyon was old enough to compare professions and futures. The spinning business, preparatory step to the weaving he already knew, appeared to hold a brighter future than that of a webster. Knowing something of the process necessary for cotton spinning, he again entered into an apprenticeship agreement. He worked as a piecer, joining one thread to another, uniting what without proper care could produce sloppy yarn and threads and be unacceptable to sell to the weavers. Various types of spinning machines were in use throughout Scotland; Lyon worked with an extremely large one which operated with 150 spindles. It was likely a waterpowered “mule,” a machine perfected by Crompton, based on earlier models (Mercer 118). Lyon’s height and long arms helped him reach the spindles quickly, making sure that threads and yarn were continuous, even, finely spun. In an autobiographical sketch he referred to himself as an “outside Piecer,” a reference not quite clear as to whether he worked outdoors preparing the cotton, or whether he labored outside the machine as opposed to the smaller workers who tended the machinery inside, or under it.

Within two years, in 1817, when John was fourteen years old, he mastered the necessary tasks such that he was able to replace the master spinner whenever the master went away. He continued receiving salary increases, earning sixteen shillings every two weeks, certainly enough to support himself and to aid his mother. In 1819, after John had spent three-and-a-half years in this promising apprenticeship, the master informed him that the firm was confronting the same economic crisis as the weavers. All the “outside boys” were released from their obligations, in essence fired, and girls were hired in their places; young girls did not demand the same pay as male apprentices who intended to make a career in spinning.

Neither John’s dismissal from weaving nor his leaving the spinning trade casts doubts on his ability or desire to work; the whole cloth and manufacturing business had reached what he later called a “dullness,” a type of recession in which workers were plentiful and salaries depressed, but in which prices for goods rose. In such conditions the younger, less-skilled laborers lost not only their present jobs but also their future; they would not become masters of the trade. At sixteen years old, John had tried to perfect skills and win the necessary certification in two trades and had been foiled in each. Quite independent and mature for his sixteen years, he engaged with a weaver as an assistant but not in a formal apprenticeship. During this year, late 1819 and 1820, he became sensitive to the political structures extant among workers, especially the private, secret unions formed by the weavers and spinners. He was definitely sympathetic with them and likely participated in their meetings. The government recognized that many weavers had become radical and were dangerous to bureaucratic order and image.

In his scattered, incomplete personal memoirs, Lyon rarely gives dates of events in his life but merely states that he worked for a year here or three-and-a-half there. Piecing these bits of information together tells us that his third job, assistant to a weaver, must have ended in 1820. He recalls a strike that “lasted a few weeks, when the spinners [and weavers] commenced firing the buildings.” Historian David Daiches confirms the protest, the breaking of looms and machinery owned by wealthy landlords and the spreading of fear through the populace (54). Lyon saw and wrote of the public whippings and the trials, and he knew some of the men who were “transported” for ten or fifteen years as a result of their protests and illegal activities. In Lyon’s later years, his writings criticize weavers and spinners for their greed in desiring more than the “good” salary they were already making, but his activities and writings in Scotland demonstrate strong rapport and sympathy for the working class—the home craftsmen, the small businessman. Participation in and observation of the 1820 strike, more than any other single event, interested young Lyon (barely seventeen years of age) in politics and made him a champion of fair wages and better conditions for the worker.

Despite the strike, he earned enough during the year to supply his simple needs of food and clothing; his shelter was still home, with mother. But during late 1820 or early 1821 my mother entered into a new life with a man I had seen in the house sometimes. I did not like his appearance, and whether this was through prejudice, or a hatred I had to step-fathers, I cannot say. However, I fell out with my mother about it and left to face the world on my own account, (ms)

As a romantic boy, he felt predictably annoyed, upset, and betrayed. He would have preferred that she remain close to the memory of gallant, dashing Thomas, the departed father who needed defending from condemning aunts and uncles. After nine years, Thomas was only a shadowy memory to the adolescent, but a memory that should be maintained, honored, kept inviolate. Janet did not feel the same need; widowed since age thirty-four, Janet was lonely, barely existing above a poverty level in a town that had lost much of its charm for a weaver. Now in her early forties, she met another man, perhaps a widower, and began a “new life” with him.

Lyon moved away, quite without a negative scene. At seventeen, he was earning his own keep, had developed a strong sense of self-reliance, and was considered an adult both by himself and society. He left home, found a flat of his own, and continued his work and leisure activities. He seemed little changed or traumatized by the break with a home in which he had spent precious little time since he was nine. His apartment was also somewhere on the east side of town, the older section with cheap rents and run-down buildings. For the next four years he spun and wove, then returned to his dreary apartment which was often shared with other male companions. He prospered in friendships and confidences but not in finances.

Love and concern for his mother continued, but in future writings he rarely mentions her. A poem, “Regret,” written many years later in Utah, may refer to his own mother. Although the pretense of the poem suggests a daughter yearning to counsel with an absent mother, the circumstances and wording suggest incidents in Lyon’s own life.

There’s not a child that lisps the name of mother

But that sweet sound runs thrilling through my brain,

And brings the mem’ry of past years together

Of her I loved, and ne’er may meet again;

In fancied vision oft I see her smile,

And hear the voice, which once glad’n’d my sad heart;

Sweet words of hope, that ling’ring still the while

Whisp’ring we’ll meet though severed far apart,

. . . .

O! mother dear! could I but fly to thee

For one brief hour, to lean upon thy breast,

And hear thee whisper, “Truth has made me free,

Now all my fearful troubles are at rest,

And thou art mine, more lovely, long lost child,

Though, runaway! again I have thee caught.”

Oh! could I hear such heav’nly accents mild,

And know to thee salvation has been brought:

This world were nothing, for the priceless prize

To have my mother, for its sacrifice.

. . . .

O, mother, will I e’er see thee again?

(Songs of a Pioneer 70, 71)

Lyon’s concern is here more spiritual than mere human communication; his mother never joined the Mormon church and he desires that she too have its blessings so that she may achieve full salvation. He sees family harmony in the hereafter, with truth restoring unity. Yet the poem ends with a despairing question—will he ever see her again? In his frequent autobiographical sketches and poems, these are the only two direct mentions of his mother in later life. He certainly visited with her while he was living in Glasgow; in later years, when he had a job that required travel over central Scotland, he must have stopped off to see her. It is logical that she adopted the name of her second husband, now not known, and died in anonymity. Genealogical records show her death in 1832, but this date is taken from family tradition and memory rather than written record. Despite the paucity of references to her, she was constant, hardworking, loving. Seventeen or eighteen years younger than her first husband, she worked, scrimped, and organized a household that kept disintegrating. The “break” with her only son, in 1820, must have torn her and hurt deeply.

Lyon went on with life: ‘I was confident I would do well if I attended to my work. I removed from one place to another as a journeyman weaver, and made nothing of it; being my own master I sought pleasure in dancing halls and in sparring . . . and in the theatre” (ms). In later life, in his brief “Forest King” sketch, he tends to look down on this period as a time of frivolous folly and youthful waste, but his stories and creative literature add a further dimension. Perhaps even in 1819, but surely by 1820, he again commenced formal study in the evenings on his own initiative. Glasgow was proud of its numerous “charity-schools,” which in 1821 taught nearly 7,000 students (Glasgow Delineated 54). The term charity indicates that the schools were free, or nearly so, and, hence, especially available to lower classes. There was a small stigma that they might be inferior to some special private schools, but they nevertheless filled a vital role. Some of these free schools taught basic reading, math, and writing skills in the evening; Lyon attended such a school. He recognized his inadequacies—only a year-and-a-half of formal training—and decided to improve himself. He labored during the long working hours and, for a year or more, studied in the evenings. Seven years had elapsed since he had engaged in any formal learning; undoubtedly he had forgotten certain specifics but had retained sufficient skills during his apprentice years to read simple prose. Now, older, generating his own need and enthusiasm for learning, he studied with precise purpose: he saw the fluctuating, falling status of the webster and knew that he must be something more if life were to be fulfilling. A simple answer—more education—would allow him the possibility of change and personal development in changing, developing times.