“Fair Home of My Choice” (1853–1889)

T. Edgar Lyon Jr., John Lyon: The Life of a Pioneer Poet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 213–84.

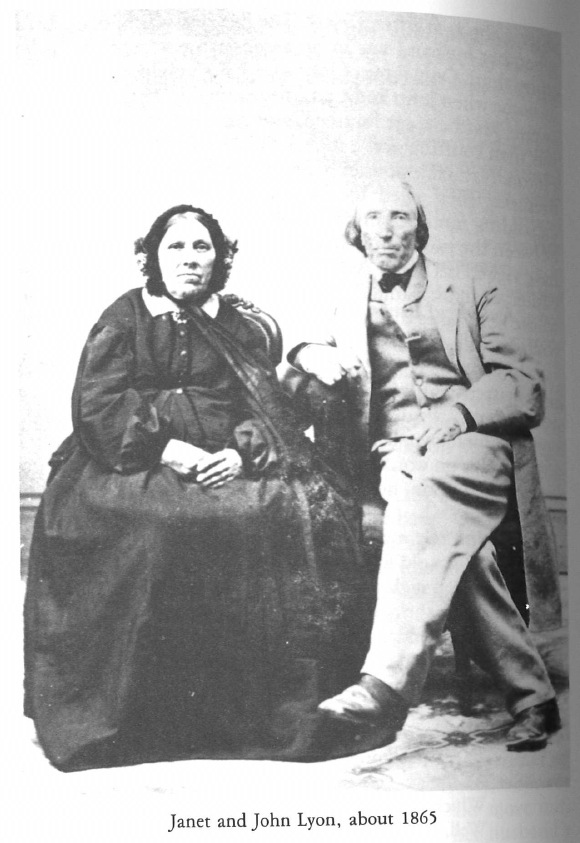

The Lyon’s old-world “hame” soon became “home” in the promised Great Salt Lake Valley; Scottish words and customs gave way to the language and culture of the American frontier and to the value system of Mormonism. “Babylon” had been washed away in the rebaptism of October 1, 1853, and John, Janet, and their five children began their “new life” in association with businessman Edwin Woolley in one of the central wards of the city. Despite the generosity of the valley Saints, the Lyons nearly starved to death during the cold, dark days of their first mountain winter. They existed mainly on donated potatoes and roots grubbed from the snowy foothills. A son recalls that “for about six months [the family] lived almost entirely on potatoes and salt, and were better off than some who did not have the salt.” [1] It is likely that some of the family spent the winter in the box of the wagon that had been “home” on the prairie. In the midst of eking out a meager wintertime existence, Lyon and his wife took occasion to receive their sacred endowments in the Council House, the spiritual fulfillment of their 8,000 mile physical ordeal as well as their years of anxious waiting. [2]

The lives of the Lyon family now revolved fully around Church activities. On January 12, 1854, Lyon was ordained a seventy and was sustained as the second of the seven presidents in the newly organized 37th Quorum of Seventies. Cyrus Wheelock, Lyon’s friend from mission days in England who also trekked across the plains in 1853, was the senior president. Most of the quorum members had also come to Utah in 1853; most now resided in the valley, but some had taken up residence in Nephi City, Grantsville, and Lehi (Deseret News, March 30, 1854). Lyon, age fifty, and ten to fifteen years older than the other quorum members, was known because of his published poems and hymns and hence was accorded a senior role in the group. Church leaders created the quorum to fill a social as well as a spiritual role for its members. The group held its first regular meeting on Tuesday evening, January 31, 1854, in the Eighth Ward Schoolhouse. Subsequent meetings convened in the Fourteenth Ward School, usually on Friday night. [3] At the second meeting, Lyon suggested that they “form a lyceum—for the purpose of quickening [the] members” (Minutes, February 3, 1854). Like the fraternal organizations he had known as a student in Kilmarnock, Scotland, and other organizations with which he would soon associate in Utah, the group selected topics for mutual edification. During the slow winter months, they chose polemical themes two weeks in advance, assigned two men to defend differing viewpoints, and then heatedly discussed the proposition. Members were to take turns suggesting discussion topics, yet the minutes frequently show it was Lyon who “was asked to moot a question for the next meeting.” The types of questions discussed indicate the broad interests of the group as well as their willingness to tackle heady theological issues:

1. Who will be at the head in the Millennium, Juda or Ephraim?

2. Has man a free agency in this state of probation or not?

3. Will man’s next state of existence be a temporal or a spiritual one?

4. Is zeal without knowledge a dangerous thing?

5. Has astronomy, geography, or chemistry been of the greatest service to man?

6. Government.

7. Origin of man on earth.

8. Military tactics.

9. Economy.

10. Sinning against light.

(See Minutes, 37th Quorum of Seventies)

Fortunately for the Lyon family and other new arrivals to the valley, the spring of 1854 came early to Utah. By March 17, attendance at the Friday night quorum meetings had dropped off “owing to the increase of business, consequent of fine weather.” Few meetings were held during the “seeding” season; Lyon and the others had more urgent tasks to perform. “During the second year [1854 or 1855] I built a small log house in the 20th Ward. There were few houses from Eagle Gate up to my house, perhaps four or five” (Lyon, fragment, 3). The house was actually in the Eighteenth Ward at the time it was built; the Twentieth Ward was divided from the Eighteenth in 1856. Family members began the heavy tasks of ploughing and planting the anemic-looking, clay-ridden soil, so different from the dark loam of Great Britain. A few years later, after the seedling trees had grown and the acre garden was producing food, Lyon eulogized his humble plot:

How sweet on the bench-land’s the breeze of the morning,

How fragrant the odor all nature distills,

Where th’ sun rises o’er the high mountains, adorning

The age-shelving hollows dividing the hills!

Around my log-cabin the peach trees are blooming—

The grape-vines and currants their beauties impart,

While the sweet-scented flowers the air is perfuming,

To gladden the eye and enliven the heart.

Fair home of my choice, ‘mid the dark Rocky Mountains!

I love thee far more than my birthplace can name!

. . . .

Our orchards, like Eden, in fruitfulness bear;

With my fam’ly around me, thou’rt more worth revering

Than all the gold tinsel that Bab’lon can wear!

(“Fair Home of My Choice,” Songs of a Pioneer 39–40)

The land the Lyons moved onto was free; logs for the tiny cabin came from the nearby hills, dragged or carried to the construction site by all the Lyon family Lyon, his sons, and kind neighbors completed the log home during the summer, at which time Lyon returned favors gratefully accepted the previous year by receiving into his home many of the Scottish immigrants who trekked into the valley each fall. David McKenzie, who later became one of the most popular actors in the Salt Lake Theatre, records:

Robert G. Taylor and myself arrived in the city from Scotland in October, 1854. We called at John Lyon’s to whom I had a letter of introduction, where a convivial party was being held. During the evening Brother Taylor delivered two recitations, and so impressed Brother Lyon with his ability that he invited him to attend a meeting to be held in the Social Hall, only two evenings later, for the organization of a theatrical company to play through the winter. Brother Lyon held the position of critic in the association, hence his influence. He introduced Brother Taylor to President Brigham Young at that meeting. (Cited in Pyper 52)

From the quotation it is evident that the Lyon house was a welcome haven to new arrivals and—just as it had been in Kilmarnock—was a center of social activity.

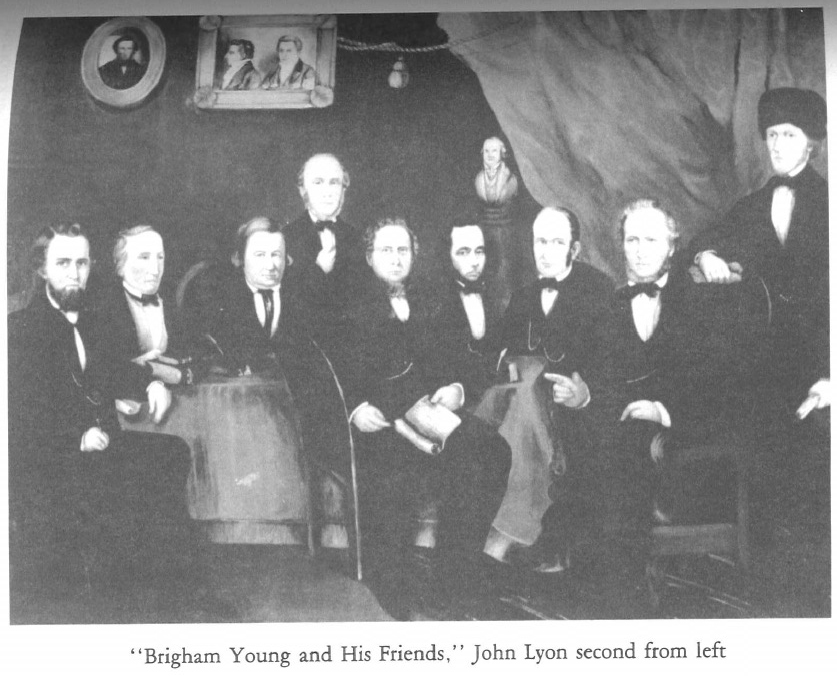

Lyon had joined the Deseret Dramatic Association and was diligently recruiting new members; Brigham Young, who so warmly touted the civilizing effects of wholesome drama, was also an enthusiastic member. Lyon had already been named “critic,” a job that consisted of assisting in the selection of plays for performance, training and coaching the actors, and later reviewing the association productions in the Deseret News. A large number of Scottish immigrants dominated the association, giving a decidedly British accent to its performances.

Shortly after his arrival in Utah, Lyon began collaborating with the Deseret News. His reputation as the foremost Mormon poet, one who had published an entire book of poetry, gave him easy access to the pages of the Church-controlled weekly. Similar to other newspapers of the day, the News usually carried an original poem in each issue, prominently displayed on the front or second page of the paper. Such a policy encouraged local talent and stimulated aesthetic endeavor by many men and women. Lyon wrote for the Deseret News and later the Mountaineer, the Mormon, the Contributor, Tullidge’s Quarterly Magazine, the Millennial Star, and a few other smaller journals; the Mormon literary field was truly white and ready for experienced journalists to thrust in the pen.

Lyon’s first signed piece written in the valley, entitled simply “Reflections,” appeared in the Deseret News in early January of 1854. The words of the poem are the tragically poignant feelings of R. W. Wotcott “on the death of his wife, Calista . . . , arranged in a poetical form by Elder Lyon” (Deseret News, January 5, 1854). One can easily imagine the anguish of a recently arrived young Saint (Wotcott), whose weakened wife did not make it through the first valley winter, and who came to a recognized poet asking for a suitable assemblage of words in which to wrap his loss and despair. Lyon willingly agreed to help his newly made friend and arranged the fifty-line poem in simple rhyme:

Calista! Thou wert dear to me,

Ere life’s short sand was run;

And dearer now thou seem’st to be

Than aught beneath the sun.

. . . .

Inspiring hope come closer, cling,

That day is drawing nigh,

When we shall meet, and all shall sing,

That death himself must die.

When from the ashes of the tomb

Calista will arise.

While “Reflections” is poignant, Lyon’s first Zion-inspired poem, “An Eastern Fable,” is surprising; it was not written in praise of the valley, nor is it a eulogy of Brigham Young, nor is it spiritually uplifting. It is, rather, ribald humor directed at the husband in a polygamist marriage. The practice of Mormon polygamy had only been made public in mid-1852, and Lyon was careful not to criticize openly that sacred, sometimes onerous, religious obligation. Consequently, he set the poem in far-off Arabia, surely wanting to avoid any direct association with the same practice in Utah. The Deseret News published the poem on January 26, 1854, so Lyon must have written it during the first three months after his arrival in the valley, quite likely basing it upon his observation of some infelicitous polygamous unions. Through literary displacement he exposes the not entirely unexpected human strife and struggle possible in any polygamous union.

Most non-Mormons viewed polygamy as a crude throwback to an uncivilized era, one of the relics of barbarism, as mentioned in the 1856 Republican platform. Others, among them Mark Twain and Artemus Ward, whom Lyon would later meet, turned polygamy into fun and frolic. And while Lyon was aware of the serious aspects of polygamy—its potential for conflict, its joys, and its doctrinal importance—he chose in this poem to emphasize its humorous side.

AN EASTERN FABLE

In the calm sunny shade of an Eastern clime,

Lived an old loving pair quite jocose,—

There the laws of the country had made it no crime

For a man to get wed to as many in time

As would crown him with honors, celestial, sublime

In the harems of Allah’s repose!

With this old loving wife he had lived many years,

‘Till his head became silvered with age,

When a buxom young dame, as the sequel appears,

Struck his fancy to wed her, as one of his dears,

In the nuptial bond which affection reveres,

So, they lived like three birds in a cage.

Both were loving, and lived on the happiest terms,

And the old man, enhanced all their care,

But the most happy moments of life, has its germs

To embitter, as well as to please with its charms,

More especially ‘mong women, where life’s all alarms,

So it turned out with crazy nob’s hair.

The youthful one loved him, and wished he were young,

And to make him look blooming, and gay,

She pulled out the white hairs in handfuls and flung

It indignantly from her! as if it were dung,

For she felt, as she pulled it, as if she were stung,

She so hated the color of gray!

The old matron too, loved to see him look bright,

And to make him look sage-like and bland!

She made it her practice to wash him each night

And when dressing his head it was all her delight

To pluck out the black hairs, that mixed with the white,

‘Till his head was as bare as her hand!

Old crazy nob knew not how matters went on,

Till he looked in the mirror, and there,

To his grief, he perceived his hair was all gone!

E’en the tuft on his crown, with the rest it had flown,

Then he silently stroked down his pate with a groan,

And ran off to his wives in despair.

“Oh! you vampires,” said he, “you ingratiate crew,

Look you here, at your taste, you vile baggage,

With your perfumes and oils and combing you’ve drew

Ev’ry hair from my head, that when most, were but few

And my tuft, I can’t see e’en the place where it grew.

“You’ve left me as bare as a cabbage!

“Ah! why did you do it? I would not for gold,

What you each, have been madly pursuing;

Don’t you see all my hope of salvation is sold,

Hath not Allah, moreover, by Omer foretold

How wives, to their husbands, should matters unfold,

That each might know all that were doing.”

But to wind up this fable of fondness and frown,

And to put all the parties aright—

They made him a wig, with a tuft on the crown,

One half of it white! and the other dark brown,

And when he walks out with his wives thro’ the town,

Each cling to the brown and the white.

(Songs of a Pioneer 42–44)

The poem’s tone and rhythm are happy and carefree, even giddy. The theme, that polygamy has its problems as well as its delights, is an insider’s view, not accessible to non-Mormon humorists. Indeed, humor serves to humanize what in most official pronouncements is never discussed—conflicts and jealousy. The supposed “Eastern clime” of the poem is merely a disguise to shift identification from the author or Mormons in general. A close reading of the text shows that Mormon ideology and geography are pervasive throughout the poem. Lyon observes that in this Eastern land polygamy was necessary to “crown him [the main character] with honors, celestial, sublime,” a teaching that Lyon heard directly from Brigham Young. The simile comparing a bald head to a cabbage rings more of agriculture in Utah than of desert Arabia. Further, evening strolls with one’s wives were hardly a part of Moslem culture. Wigs were unknown in the Arab world of bushy dark hair. In short, the whimsical poem obviously deals with polygamy in Mormon Utah.

Two of Lyon’s other early poems (1855) written while in the valley portray his activities, his values, his joy of pioneer life, and his praise of those who toil with their hands:

Let soldiers sing of battle fields,

And sailors of the seas,

The miner of his golden stores,

The wealthy—pow’r and ease;

But I will sing of canyon life,

Of rocks, and valleys deep,

Of mountain trails, and snaggy roads

Along the winding steep.

(“The Woodman’s Song,” Songs of a Pioneer 11)

The 1855 “Home, Sweet, Sweet Home” is a poem from a man who has eagerly accepted the preachings of Brigham Young about farming and who finds himself thoroughly happy in his new life:

We’ve wealth in our cornfields, the gold mines can’t give;

And health in the water, and air breeze to live;

Then who would exchange for a king’s palaced dome,

With his minions and power, our own peaceful home?

Home, home, sweet, sweet home—

With friends, wives, and children, our own mountain home!

Then let us still live, where the fountain of love

Flows with life-giving Truth from the mansions above;

In “Ephraim’s fat valleys,” where fear will ne’er gloam!

The day-star of hope, of her glory to come!

Home, home, sweet, sweet home—

Ah, who would exchange for this world, their home?

(Songs of a Pioneer 18–19)

Early in 1854, Lyon had consulted a prominent English gentleman, William C. Staines, who likely knew more about horticulture than any other person in the valley Staines offered fruit trees and scores of different seeds for sale; he had reputedly lost 100,000 seedling trees to the 1848 crickets but was again in a prosperous state (Evans 414). Staines and Lyon established an admiring and enduring friendship, one that would be further cemented both by their working together in the Endowment House and the territorial library and, shortly, by a plural marriage. Staines’s diary notes “Mr. Lyon at my house” (March 2, 1854). No details of the visit are given, but the two men likely discussed planting as well as the LDS endowment.

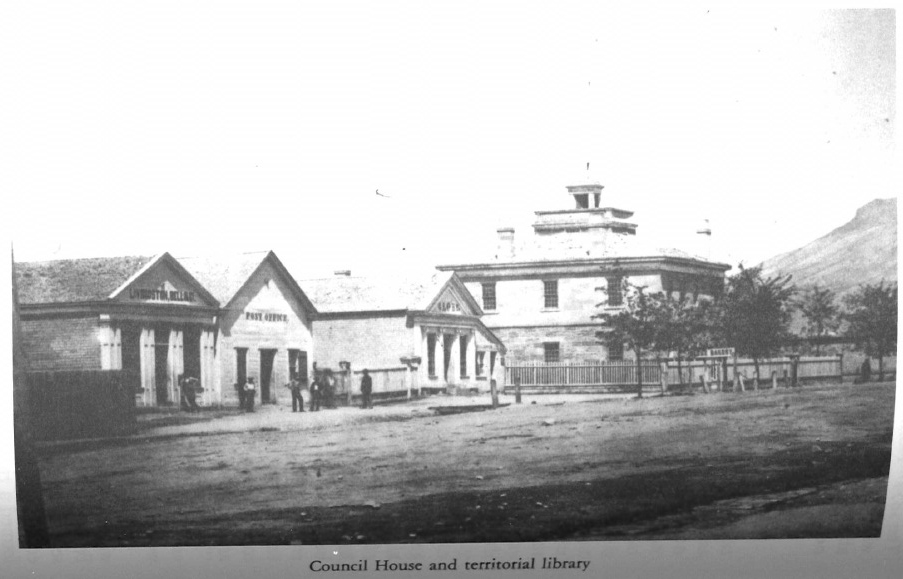

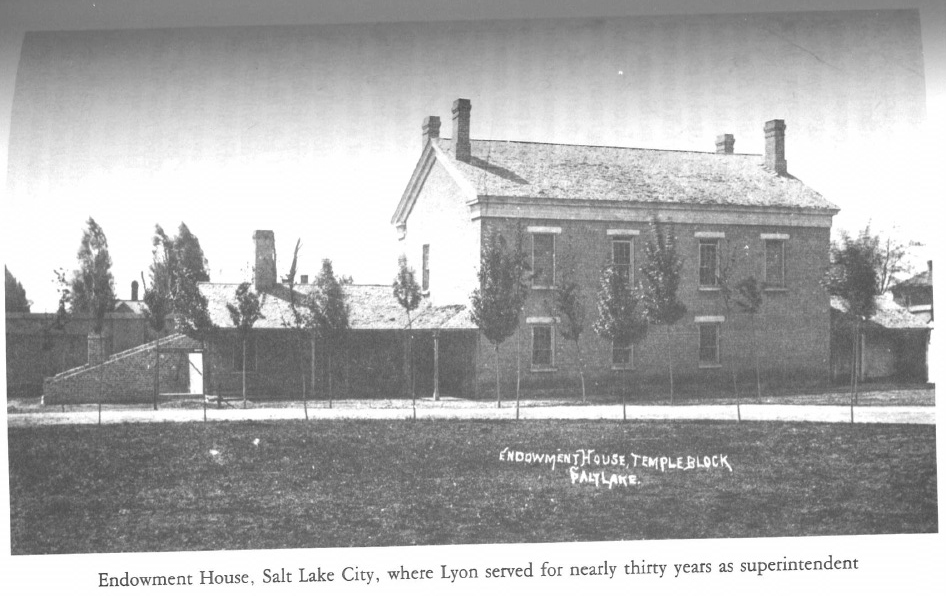

Staines was in charge of quarters for the Council House, where he began conferring endowments on the faithful on February 28, 1851 (Staines, “Reminiscences” 123). He also served as territorial librarian, shepherding some 3,000 books ensconced in the same building. The two British gentlemen formed a rich friendship that lasted until Staines’s death in 1881. William had come to the valley in late 1847 and by 1854 enjoyed the close friendship of Brigham Young and other prominent businessmen in the valley. Staines asked Lyon to function as an unpaid assistant in the library. When in 1855 the Endowment House on the temple block was nearing completion, Lyon was appointed to Staines’s old job as doorkeeper, recommend-checker, and organizer of sessions, and was given the title of superintendent.

Among the many topics discussed by Staines and Lyon was matrimony. Staines had married stately Elizabeth Turner in 1852 but had had no children by her. Lyon’s hearty eighteen-year-old daughter Lillias had caught his eye, and the pressures he felt from friend Brigham to again marry prompted him to propose a polygamous union with Lillias. The Lyon family had only become fully aware of the practice of plural marriage during the previous year, but by 1854 they were prepared to accept and participate in it. Consequently, thirty-six-year-old William married Lillias Thomson Lyon on October 30, 1854, in the sacred rooms of the Council House. No extant diaries or letters record the feelings of Staines’s first wife, those of Lillias, or those of her parents; both deep rejoicing and some serious sadness must have marked the day. Staines later married two other women, but he had no children by any of them.

Despite being in Zion, Lyon and Janet still had to attend to the practicalities of making a living. For the first few years in Salt Lake, Lyon took small jobs, mainly carpentry and weaving, to supply an income. He had brought tools from Scotland with which to ply his home weaving trade. He built a loom in his home and began contract work for a few customers. Brigham Young paid him a small fee to teach his daughters to weave, and for many years Lyon regularly visited the home of the President. One daughter, Maria “Young Dougall, recalls that “Father had his own weaver, John Lyon, and the weave room often turned out plaid” (Jensen 611). Payment for Lyon’s services was generally made in food and household goods taken from the tithing stores. Lyon may have also labored on the public works project to build a wall around Salt Lake City during late 1853 and 1854; the wall was never completed, but it did serve “to keep the English and Danes at work” (Arrington 112).

In August 1854, the 37th Quorum of Seventies resumed meeting. Just as had occurred on many other occasions in which Lyon had started out as second in command but had soon become the leader, in late 1854 he became the de facto senior president of the quorum, functioning in that role for the next thirty years. Cyrus Wheelock—the theoretical leader of the quorum—was either away from Salt Lake on business, serving as a foreign missionary, or disaffected from the Church. Consequently, the leadership role fell naturally upon Lyon. Meetings were switched from Friday to Saturday evenings to try to accommodate the needs of quorum members. Lyon suggested that they hold a testimony meeting once a month and invite their wives to participate in it; Lyon became the “great admonisher,” urging “the brethren to grasp at all intelligence,” to write out the talks they were giving in the sessions, to “improve their time and talents,” to be “moderate in all things,” and to be “cool and collected in their acts and remarks” (Minutes, August 26, 1854). He asked how his companions in the quorum stood with regard to tithing and gave an account of his own actions relative to that law; and he instructed the men to learn foreign languages, especially Italian and German (Minutes, December 16, 1854). In time the quorum members switched their meetings to Sunday, and once a month their wives participated in a testimony meeting—an apparent beginning of present-day sacrament and testimony meetings at a time when no other such gatherings were held in the Church.

Lyon also participated in other organizations. Just as the Saints in Ohio had formed the School of the Prophets in Kirtland, so the Saints in Utah used the winter months to form adult schools for continued learning. Energies devoted to agriculture and home-building in the summer found outlet in spiritual and intellectual activities during the chilly season. Lyon probably belonged to the rather elitist Polysophical Society, which was formed in December of 1854 (Beecher 146). For though he is not mentioned in contemporary records, Annie Wells Cannon in 1908 recalled that Lyon had indeed been a participant (Cannon 26).

During December, 1854, Lyon also attended a meeting to establish a philosophical society. After consultation with Brigham Young on January 8, 1855, the society’s name was changed to the Universal Scientific Society (Brigham had a personal aversion to the term philosophy, a discipline practiced by those with whom he did not agree). On February 3, 1855, approximately sixty men met in the Council House and officially organized the society. A constitution was approved, and Wilford Woodruff was elected president; seven other men were chosen to serve as vice presidents: John Taylor, Ezra T. Benson, Lorenzo Snow, Orson Spencer, Albert Carrington, Samuel W. Richards, and John Lyon. Lyon was again in good company; all the other vice presidents were Apostles or long-standing Church leaders. Brigham had suggested that this powerful group “be blended with the board of regents [of the University of Deseret] and act in concert with them” (Journal History, January 8, 1855). The society met regularly, holding lectures and study sessions in the Council House. Woodruff s presidential address established the group’s goals:

We are desirous of learning and possessing every truth which will exact and benefit mankind. . . . We wish to be made acquainted . . . with art, science, or any other subject which has ever proved of benefit to God, angels or men. The proverb that knowledge is power is a truth which cannot be denied. . . . We would be glad to see all Israel unite in joining this Universal Scientific Society or branches of the same.

Elder Woodruff asked members of the society to bring books to form a “library”; to collect birds, insects, and rocks from all over the world for a museum; and to establish a reading room. Both by title as well as by plan the group was thinking big. Records were kept; books and materials were gathered. Just how the books meshed with the territorial library—which was in the same building—is not clear; but since William C. Staines was apparently not an active member of the Universal Scientific Society, and since Lyon was, Lyon became the key figure in cataloging and arranging the items collected by the society’s members.

During 1855, then, Lyon’s life revolved around the 37th Quorum of Seventies and the several societies to which he belonged. He spoke each week in his quorum meeting, at once opposing “individualism” and urging the brethren to cooperate and aid each other. He made this plea for cooperation especially for the control of a serious grasshopper plague. Once, in excusing his own absence from a previous meeting because of illness, Lyon observed that he “never had any confidence in doctors . . . always thought them knaves, who would get all they could, and then you might die [anyway]” (Minutes, October 21, 1855). Lyon advised members to cultivate faith and not visit local doctors. The minutes of quorum meetings indicate that he continually admonished his quorum brethren to improve themselves, to participate more fully in church and civic activities, and to consecrate themselves and their goods to broader causes than just themselves.

Lyon also continued assisting his son-in-law, William Staines, in endowment work at the Council House. In 1854, Church leaders had proposed the erection of a two-story adobe Endowment House on the temple block, which construction had begun in the summer of that year. By December the workers had “placed the rafters on the new building” (Journal History, December 6, 1854). Good weather had allowed work during much of the winter, and by the spring of 1855 the plastered, painted rooms were ready for dedication, causing George A. Smith to note that “the endowment house is finished and is a beautiful building” (Journal History, April 27, 1855). On Saturday, May 5, 1855, Brigham Young, his counselors, and other prominent Church leaders including Staines met in the newly completed building on the northwest corner of the temple block, and in “an upper room . . . [Heber C. Kimball] dedicated the same to the Lord” (History of Brigham Young, May 5, 1855). Three couples completed their endowments, a sacred religious ceremony, and were sealed that day. The structure was intended as a “temporary temple,” designed for use only until the permanent House of the Lord was complete. However, sealings were performed in it even after the St. George Temple in southern Utah opened in 1877. In fact, the Endowment House was used for endowment work until November of 1889.

At the dedication of the building in May, 1855, Brigham Young affirmed that the Spirit of the Lord would be in the sacred rooms and that “no one would be permitted to go into it to pollute it” (Journal History, May 5, 1855). To maintain the sanctity of the place, a doorkeeper had to be present. Consequently, in March Brigham named John Lyon as superintendent of the Endowment House (Lyon Biography). Lyon occupied a desk in the entrance room on the north side of the building. For thirty years, until 1885, he went, at least once and sometimes two or three times a week to perform his sacred duties in the Endowment House. Here he had occasion to greet and counsel with all who came to receive spiritual ordinances. As doorkeeper, he would have met virtually all active LDS members in the area. Scotsmen who came to the Endowment House often mentioned Lyon in their letters home. James B. MacNeil wrote the following to relatives in Airdrie, Scotland, part of Lyon’s 1852 jurisdiction near Glasgow:

When I came down from Cottonwood the Bishop was advising all the young Men that were worthy of it to go through the house & receive their endowments. . . . So I got a recomend from the Bishop & went down & got My endowments & I Seen old John Lyon, alias the Lion of the Lord. I Made Myself acquainted with him & when I was coming away he told me to give you his best respects. & Father he give Me a good advice I can tell You. So I wear My Garments Now all the time & I think it done Me good.[4]

Lyon’s pep talk made MacNeil feel good, but it also helped the “Lion of the Lord” feel the importance of his job.

Lyon’s official title was superintendent of the Endowment House; he actually carried out administrative work similar to that done by LDS temple presidents in the twentieth century. Lyon apparently received a small salary for his work, again paid in commodities rather than cash. As soon as he had checked “recommendations” for each individual and had formed a “company,” Lyon participated in the endowment session himself, almost always taking the role of the preacher; his poetess friend Eliza R. Snow was even more regular than he, always taking the part of Eve. Records show almost no other woman but Eliza officiated in the Endowment House during the 1850s, 1860s, and early 1870s. Another poet, W. W. Phelps, always acted the role of the devil, except when he was sick, at which time Lyon took the adversary part and Abinidi Pratt became the preacher (Endowment House Records, film 183, 406).

Another of Lyon’s tasks was to arrange for a doctor to be present at the Endowment House, where parents brought their children to be circumcised when eight days old. Early Church leaders felt that they were truly reestablishing Israel and so had to restore all known ordinances; the substitute temple was a logical place to perform the covenant ceremony of circumcision (T. Edgar Lyon, Interview, 1975). Lyon worked under the direction of Heber C. Kimball, the chief administrator of the House. Lyon now enjoyed an important ecclesiastical identity—he was working for the Lord in fulfillment of an apostolic prophecy. “Years earlier, likely in 1848,

Brother Lyon had expressed to Franklin D. Richards his strong desire to emigrate to Zion, though doubtful that his hope would ever be realized. Thereupon the latter promised him that he should not only emigrate to Zion, but should there become a door-keeper in the House of the Lord. Literal fulfillment of this prophetic promise was later seen in the service rendered by the venerable poet as door-keeper of the old Endowment House. (West 84)

The year 1855 also witnessed the marriage of the Lyon’s twenty-year-old son, John Jr., to Mary Elizabeth Toone, an English girl then residing in Salt Lake. John and Mary were married on April 18, just two days after her fifteenth birthday. Mary gave birth to twelve children during the next twenty-five years; six of them died in infancy. After their marriage, the newlyweds took up residence in the Twentieth Ward, near the Lyon family home.

During the 1855 October general conference of the Church, Brigham Young called twenty-seven men who 1 ‘were unitedly and unanimously voted to go on missions to the Saints in Utah Territory” (Journal History, October 8, 1855). Many of the men were Apostles; John Lyon was among those called to perform this “home mission.” These callings indicate the beginnings of the well-known 1856–57 “Reformation Movement.” In his 1855 October conference talk, Brigham railed on the Saints for their complacency and outright neglect of duty, noting that “many are stupid, careless and unconcerned . . . greedy, . . . neglect their prayers” (Journal History, October 8, 1855). Home missionaries were to cleanse the Church of these curses. A week after the men were called to the mission, a planning meeting was held in Parley P. Pratt’s home in which preaching districts were organized and the concept of quarterly conferences in towns and stakes (a geographical designation) was suggested as a way to reach all the people. Lyon received the assignment to work in Salt Lake and Tooele counties in company with his old friend from Great Britain, Levi Richards, as well as with Joseph Young, Wilford Woodruff, and Parley and Orson Pratt. These “home missionaries” preached long and loud; Woodruff notes in his journal that after the first local meeting “evry missionary present had a cold sore throat and was hoarse” (Wilford Woodruff’s Journal, October 20, 1855, 340). On November 10, 1855, at the schoolhouse in Tooele, “Lyon Addressed the people for about one hour” (Wilford Woodruff’s Journal). A clerk summarized Lyon’s lengthy preachment as follows:

I feel very weak; I did so in the old country, but much more so in this, where there is so much of the priesthood around me. I have wished that what I had learned in the world was taken from me, for I have thought that it had done me more hurt than good. I have seen many that had enjoyed the gifts of God, that have apostatized, and said it was all a delusion. Some are in the faith when the sun shines, but when the grasshoppers eat up their grain and all they planted, they feel as though they want to leave, and try to find a better place. When we have the spirit of God we feel well, and are blessed; but when we do not have it, we do not know what to do, and we do not prosper temporally nor spiritually. (Journal History, November 11, 1855)

The thrust of Lyon’s sermon is clearly that of a reformation sermon: members must repent of all sins or be cut off from the Church.

The home missionaries set up regular quarterly conferences in the towns and stakes in their assigned counties. And Lyon traveled and preached with his Apostle friends during late 1855, 1856, and most of 1857. The missionaries’ messages were very similar at each conference: consecrate property, forsake worldly pursuits, be honest, cut off backsliding members, avoid debts, keep homes and yards clean (Larson 52–56). Lyon proved himself a dynamic preacher and faithful follower during this difficult period of the Reformation.

Lyon also continued joining many of the new organizations that formed. In 1855, he united with the “Deseret Typographical Association,” a group of intellectuals involved in printing, writing, and education. Orson Pratt and others fostered the Deseret Alphabet through the association. In early 1856, the association met in Social Hall for dancing, songs, a grand march, dinner, and a very extensive program of poetry, original songs, talks, and toasts; the gathering lasting from 4:00 P.M. to past midnight. During the festivities, association members proposed to change the name of the organization to the “Deseret Press Association,” and Lyon composed an eleven stanza poem for the occasion, “Song of the Deseret Press,” which was sung to the tune of’ ‘The Steam Arm.” The poem is one of the many special occasion poems from the author’s pen and has perhaps more historic than poetic value:

Let them sing of invention, discovery, and trade,

And mechanical arts of every grade—

Yet, there’s none of them all, be it quietly said

When compared—the Press throws them all in the shade:

. . . .

It speaks of a child raised in travel [sic], and pain,

Whom old uncle Sam cast out in disdain;

And how this same lad, grown to manhood, would fain

Prove his right to be linked to his family again.

But, where you will ask, are those stirring views

To be found without flatt’ry, fraud, or abuse?—

Where men find their level, and devils their dues?

Then read, my dear friends, the “DESERET NEWS.”

(Deseret News, February 13, 1856)

The poem expresses the curious desire to establish a better relationship with the government of the United States and indicates Lyon felt that Utah had now reached maturity. The last stanza, which had to end with the words Deseret News, is rather forced but nevertheless expresses the pride the society and Saints in general felt about the honored press.

A similar occasion, a meeting of the Press Association in February of 1862, called forth another Lyon poem:

THE PRESS OF DESERET

No printing press in days of yore

Did light and truth diffuse;

The tardy movements science wore

Cramped the unlettered muse.

But now the mind’s electric fire

Beams forth where’er we be;

The pen and press has gained a name—

Will soon the world set free.

Now intellectual science reigns,

With manners pure and chaste.

. . . .

And here in Deseret we claim

Arts—genius in each trade,

And all that gave the world a name,

May of her now be said.

And may the living spark inspire

Each freeman’s heart to glow,

Till this void waste becomes empire,

Where truth and light shall flow.

(Songs of a Pioneer 23)

This second poem, written during the Civil War, postulates a high-minded mission for the press—to inspire men to freedom through the dissemination of truth. The poem’s images (“mind’s electric fire”), its optimism about art and genius in Zion, and its universal message all make it a much better poem than the 1856 verses. Lyon served an important function as the ever-present, often-invited poem-maker at meetings of the press and numerous other associations.

In just two years in the valley, Lyon was doing many of the same types of things he had done in Scotland and England: he was now a traveling and preaching home missionary, a weaver and weaving instructor for Brigham Young’s daughters and numerous others, the senior president of the 37th Quorum of Seventies, and a leader and poet-laureate of several organizations to which he belonged: the Deseret Press Association, the Universal Scientific Society, the Deseret Agricultural and Manufacturing Society, the Deseret Dramatic Association, and others. He also took on new jobs as superintendent of the Endowment House and as assistant territorial librarian.

But if 1855 was a good year for Lyon’s personal growth, it was a disastrous one for the economy of the Territory. Grasshoppers again swarmed in most of the new-green valleys, devouring the summer crops; some areas lost all of their expected harvest; most lost over half. William C. Staines reported the loss of a half million apple tree seedings to the hopping plague (Evans 414). Heavy immigration brought an additional 4,225 hungry mouths to Zion in a single season; they, too, had to share the scarcity The deus ex machina seagulls of 1848 failed to appear in 1855; severe food shortages were universal. Then, the winter of 1855–56 blew harder and longer than any previous. Thousands of Church-owned and privately owned cattle starved or froze to death; famished Indians ran off many of the remaining weakened animals. Heber C. Kimball estimates that half the cattle in the Territory perished during the winter {MillennialStar 1856, 396–97). The area’s poorer inhabitants had to grub through the deep snows for thistle roots and mustard leaves; better-supplied Saints cut their family consumption in half and rationed as best they could (Arrington 148–54). Cooperation flourished as neighbors shared their small food treasures. The clerk of Lyon’s 37th Quorum humbly notes that one “Elder Bilhston did not want to boast, but said he would willingly give to any brother that was in want 5 or 6 pounds of flour” (Minutes, January 19, 1856). Another entry poignantly states t h a t “the brethren met but owing to the inclemency of the weather and want of wood for fuel, the meeting was adjourned” (Minutes, January 5, 1856). The suffering was borne by hungry, cold individuals who made it through the long winter months in necessary and willing cooperation. The Lyon family may have been better off than most as a result of Lyon’s work in the Endowment House; those completing their endowments (at this time members came for their own sealings and covenants only) often brought food for the full-time workers. Heber C. Kimball, in a letter to Utah bishops, urged them to send men to the Endowment House who should “bring their eggs, butter, meat, bread, and flour, and the luxuries of life to grace the tables of the House of the Lord, to feed the men and women who administer unto them” (Journal History, May 19, 1856).

The severity of the 1855–56 famine, coupled with the growing Reformation movement, also brought renewed preaching of the doctrine of plurality of wives. The number of plural marriages in relation to the population was 65 percent higher in 1856 and 1857 than in any other two years of Utah’s history (Ivins 231). As home missionary, regular guest in the home of Brigham Young, father-in-law to twice-married William C. Staines, endowment worker, and a friend to most of the Church authorities, John Lyon daily came in contact with the doctrine, its chief adherents, its supposed physical benefits, and its indispensability for spiritual progress. In early 1856, in the midst of these pressures, Lyon had a dramatic dream:

I thought [dreamed] . . . that I was in company with the First Presidency, as a guest at dinner . . . when Brigham Young asked me why I did not take another wife, as I was losing time. . . . I replied that I did not know where I could find one willing to have me. Said he, “Will you take one, if I find one?” I said “yes,” so I [dreamed] he took me out to the street and told me to go as far as I saw the rise of the road, and there enquire for a lady of the name——. In my dream I arrived at the house in quick time . . . but it seemed to be evening and rather dark. So I rapped at the door but got no answer. . . . I rapped again and a voice said, “Come in.” I was . . . in the middle of a small room having one bed in the corner, where a woman was sitting in her nightgown. I enquired “if there was a lady of the name of——[who] lived here?” when all in chorus, rang out a loud laugh, from the lady in bed, and what I supposed three others who were hidden somewhere in the room. This merry introduction wakened me out of my pleasant anticipations. (Lyon, fragment)

The dream reveals Lyon’s desire to comply with Brigham’s wish, but it also suggests that he worried about the reaction of others, particularly his acceptance by women to whom he might propose, as indicated by their derisive laughter as he approached the lady in bed.

Near the small Lyon family cabin lived another Scotsman, Robert Crookston; Lyon frequently visited with his fellow countryman and observed a sixteen-year-old English girl who served as a maid. Her father had died in Nauvoo and her mother in Winter Quarters, and the kindly Crookstons had brought her to Salt Lake City in 1852. “Often visiting this family, my mind was drawn to this girl, and plural marriage being a subject on my mind as sacred as baptism for the remission of sin,” Lyon timidly thought of marriage with the sixteen-year-old orphan:

Although I never put much faith in my dreams as revelation still I looked upon it as strange that this [house of the dream] was in the vicinity of my Scotch acquaintance’s dwelling, where I had seen this girl. . . . Some months after this I was invited to dinner in the very house of my dream . . . [by the First Presidency]. After dinner Brigham Young addressed me in the exact words, “Why did I not take another wife as I was getting old?” To this question I answered by a laugh, when he sternly asked me what I meant. I then told the three gentlemen my dream.

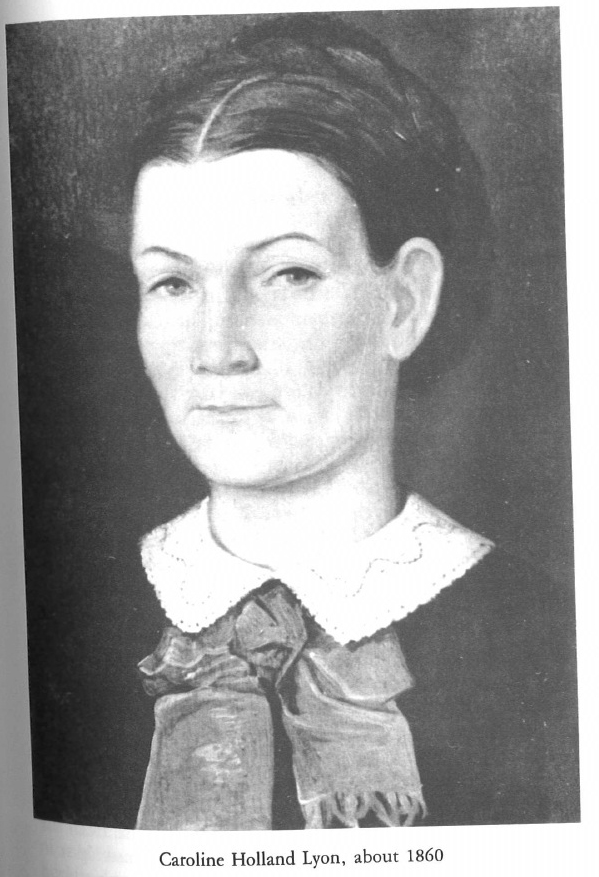

Brigham then told Lyon that the dream was truly from the Lord and that he ought not be concerned about ridicule. That very night after dinner, Lyon went to the Crookston home, talked with the young girl, and “proposed to her . . . if she would be my wife for time and all eternity, to which she answered in the affirmative. This was all the courtship we had.” On March 28, 1856, Brigham Young sealed fifty-three-year-old John Lyon to sixteen-year-old Caroline Holland in the Endowment House. Janet had also been sixteen when she married John, thirty years earlier. She was present at the ceremony and was sealed a second time to her husband (Endowment House Records).

Little specific consultation took place between Janet and John prior to this plural marriage, but a considerable amount occurred after! Young “Carrie” (Caroline) moved into the cabin occupied by John, Janet, and their unmarried children until Lyon could build her a tiny cabin on the corner of Oak and Bluff streets (3rd Avenue and F Street), adjacent to his “first home.” When Caroline finally did move out, forty-eight-year old Janet must have resented her husband’s frequent evening absences. At times, beginning in I860, Janet went to live with her married daughter, Janet Lyon Spiers, in Tooele. Still, Janet helped teenage Caroline care for her regularly arriving children; Caroline bore seven children during the next fifteen years. The last one was born in 1872, when her husband was in his seventieth year and she in her thirty-third. Only three of John and Janet’s children were living at home when John and Caroline married in 1856—Mary, age twelve; Matthew, age fourteen; and Ann, age twenty-four, who was then courting and a month later married widowed Allen Hilton. Natural jealousies between Lyon’s two wives sometimes overcame their need to cooperate and to sacrifice for the expanding family. Lyon felt some of the tension that existed between the two women living under the same roof and must have viewed his poem “An Eastern Fable,” published two years earlier, as an unplanned prophecy. The old Moslem patriarch, whose head takes the brunt of jealousies between an older and younger wife, was now uncomfortably similar to himself.

In contrast to the frustrations of polygamy expressed in “An Eastern Fable,” a short unpublished poem, “Old Age and Dotage,” written when Lyon was past eighty, affirms the joys of plural marriage in one’s advanced years. The title is a joyful play on words—old age and dote-age; the poet enjoys being doted upon, not just by one wife but by scores of them:

It surely must be quite bewildering

When old folk have no friends or children,

When nights are dark, to lead them home

As in their dotage they might roam

And wander into holes, and stumble;

Well, then they may have cause to grumble.

I’m thankful that my wife’s no bore,

Of grandchildren she has half a score

Also, a friend who’s very zealous

To see her home, I’m no ways jealous,

As she’s now past three score and ten,

Which cools her blood for other men;

Well, let her ramble where she may

While I at home in comfort stay

Enjoying sweet polygamy,

O what comfort man derives

From having half a hundred wives!

Unlike in “An Eastern Fable,” the poet now affirms the joy of polygamous marriage. Obviously, neither he nor any other Mormons lived with fifty wives, but the hyperbole serves to enhance the effect: if being doted on by one is good, by fifty is even better. Conflicts, jealousies, or the feelings of the wives are not mentioned here; the point of view in Lyon’s poetry is that of the priesthood-holding, honored male. The poem is one of those marked “not suitable” by Lyon’s son, David Ross Lyon, who in 1923 collected some of his father’s prose and poetry and published Songs of a Pioneer. Whatever the suitability of the poetry, in 1856 Lyon joined an elite group of Church leaders, perhaps no more than 10 percent at that time, who supported polygamous families (Arrington 238). Lyon had now completed one more step toward hoped-for celestial salvation.

A further cause for joy in 1856, as well as for serious concern, was the long-desired departure of the Lyon’s two married children from Scotland to America. An 1854 letter from Utah Scotsman James Brady to David MacNeil in Airdrie petitions: “When you rite let me now whereabouts Tom Lyon is. His folks never got a letter from him sinse they left. They are very uneasy about him. I am in their house sometimes” (Buchanan, Letters). Despite his parents’ anxiety, thirty-year-old Thomas was faithfully serving the Church in Great Britain, first as president of the Belfast (Ireland) Conference in late 1852 and early 1853, where he resided at the time his parents left for America. Next he labored for twenty months as counselor in the LDS presidency for all of Scotland (1853–54), and then he served for a year (1855) as president of the Hull (England) Conference. Like his father, Thomas baptized scores of new converts during his three years as full-time missionary and received praising reports on his work (Millennial Star 1855, 705). Effective January 1, 1856, he received a release from the Hull Conference and permission to emigrate; he had “put in his time” for the Lord. Thomas’s sister Janet and her husband George Spiers had also fulfilled spiritual commitments in the Kilmarnock Branch, where George served as the local president. He also kept the six-loom weaving business going, supplying money for missionary Thomas and his family. In March of 1856, Thomas, Mary Ann, and their three children, along with George and Janet Spiers and their three wee ones, left Kilmarnock for America. Both women were pregnant; “while lying at anchor [in Liverpool] the night of Friday, March 21, Sister Mary Ann Lyon . . . was delivered of a daughter, which was named Christina Enoch” (British Mission History, March 22, 1856). Thomas and Mary Ann honored their Boston-bound ship, the Enoch Train, christening their daughter with the ship’s name, however nontraditional the name “Enoch” might be for a girl. The ship could show no mercy for the new mother and sailed the next morning. The Lyon children’s forty-one day crossing was shorter than their parents’ 1853 passage but was no less rough. Mary Ann, her new baby, and Janet Lyon Spiers were sick much of the way; the captain of their Perpetual Emigrating Fund Company, Henry Rich, notes that “it required the most increasing attention to keep them alive during the voyage.” Upon their arrival in Boston, the entire company boarded a train for New “York, where Mary Ann and Janet were both “pronounced unable to proceed at present” (British Mission History). The two women’s husbands and their young children of course stayed to aid them; the forced delay lasted three years! Though saddened, the Lyons found some consolation in that by remaining in New “York they were not among the many Saints from the Enoch Train who unfortunately perished in the 1856 handcart disasters—a fate that may well have befallen John and Janet’s children had they attempted the trek. Not until 1859 could the two young couples in New “York save enough money to continue on to Salt Lake, since PEF monies had already been expended in their behalf. In Salt Lake John and Janet grieved deeply and helplessly; they would not see their children and grandchildren for three more years.

Meanwhile, Lyon’s days were filled with drama productions, with seventies quorum meetings, with work at the territorial library and at the Endowment House, with the meetings of various intellectual groups, with building a second house, and of course with planting and weeding. Yet there were plenty of evenings left for special occasions and the poetry to enhance them. July 4, 1856, despite the hint of another year of meagre harvest (it was hot and dry and crickets again abounded), was an entire day spent in patriotic celebration. Brigham Young opened with a long oration; bands, cannons, and children blended in noisy observance of patriot’s day. President Young called for toasts; Lyon presented at least six: (1) to Deseret, may she be a state, (2) to the Press of Deseret, founded in the spirit of our Pilgrim Fathers, (3) to home industry and its development and technology, (4) to the railway, may it come soon, (5) to the heroes of ‘76 and their great success for us and our children, and (6) to the stripes and stars of our Union, may it continue to unite us (Journal History, July 4, 1856). These were not exactly the sentiments usually expressed in Reformation rhetoric, but on the 4th of July they demonstrated the patriotic mood of the day. Minutes of the 37th Quorum of Seventies indicate other concerns—sermons on retrenchment, plurality of wives, consecration. In reality the Reformation movement changed the quorum meetings; they no longer discussed “worldly” topics but focused completely on spiritual commitment. Interestingly, participation dropped off at this time, and Lyon continually had to harangue nonattenders, threatening them with disfellowship if they did not attend.

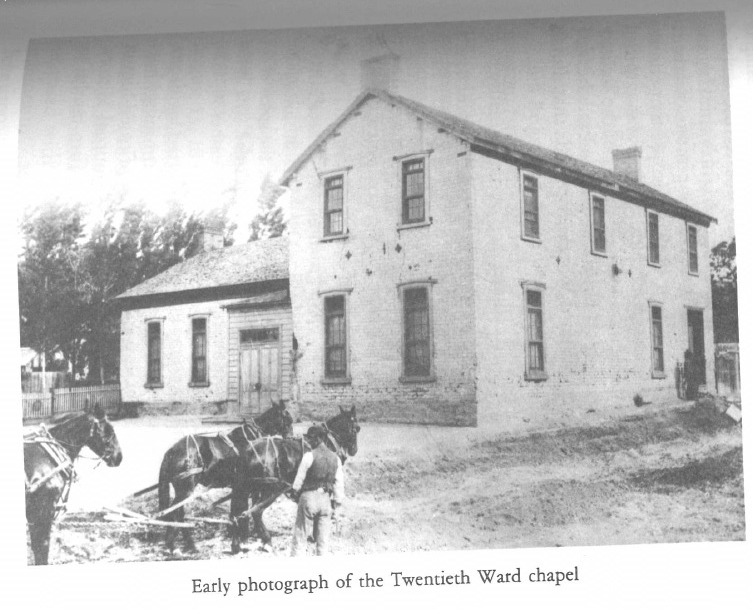

As Salt Lake grew, new wards were added; the Eighteenth Ward was divided and a new Twentieth Ward was created during October conference, 1856. The Lyon families were charter members of the new ward, two of the eighteen families presided over by Bishop John Sharp. The 1856 boundaries extended eastward from A (Walnut) Street and north from South Temple Street, extending to the mountains in both directions (Twentieth Ward History 1). The ward was home for a large number of Scottish families. Many of the ward’s charter members, and a number of those who would move in later, would have great impact on the Church: Henry Naisbitt, Joseph Toronto, William S. Godbe, E. L. T. Harrison, George Romney, George D. Watt, Phineas Young, Karl G. Maeser, A. O. Smoot, T. B. H. Stenhouse. One historian has observed that the Twentieth was one of the city’s most “intellectual and liberal wards” (Buchanan 349). Buchanan also indicates that Lyon functioned with Bishop Sharp in the leadership of the ward, likely as a clerk. The open, intellectual tenor of the ward obviously helped shape some of Lyon’s thinking and actions; conversely he helped shape the opinions of others.

On a cold December day in 1856, while quietly performing his duties at the Endowment House, Lyon was surprised by the appearance of the entire legislative body of the Territory of Utah. The Reformation activities had even entered the legal body of the Territory; Wilford Woodruff records that during the legislative session that day

it was finally moved that all members of the Legislative Body of the Territory of Utah repent of their sins & go to [the] font at 6 oclok on the Temple Block & be baptized for the remission of their sins which was Carried unanimously & the Legislature met at the font & had to fill it with Buckets from the Creek [City Creek]. . . . We Confirmed the whole Company. . . .

This was a New feature in Legislation. We believed that if we Could get the spirit of God we could do business faster & better than with the spirit of the Devel or the spirit of the world. There was 55 in all Baptized and Confirmed. The Twelve done most of the Confirming. (Woodruff, December 30, 1856)

The home missionaries, many of whom were elected legislators, also were rebaptized at this time. James W. Cummings baptized Lyon in the chilly water; Orson Hyde confirmed him in the upper room of the Endowment House (Journal History, December 30, 1856). The year ended with a firm resolve to live more perfectly in the future.

All through the momentous year of 1857, Lyon continued with Reform-oriented preaching in stake conferences, in his seventies quorum, in his homes. The Universal Scientific Society no longer met; the Deseret Typographical Association moderated its sometimes critical stance; Lyon lessened his intellectual pursuits in favor of spiritual rededication. He, Janet, their two teenage children, and pregnant Caroline, along with hundreds of other Saints, camped in Brighton, Utah, in late July of 1857 to commemorate the tenth anniversary of the pioneers’ arrival in the valley. There they heard the frightful news that an army was coming from the United States to quell the supposed rebellion in Utah. They quickly returned to the valley, and Lyon began preparations to secure the records of the Endowment House; he committed, however, to stay in Salt Lake as long as possible if the Church had to abandon the city.

On August 13, 1857, despite anxieties over an impending invasion, Lyon participated, by invitation, in laying the cornerstone at the southeast corner of the temple foundation. The uncertainty of the temple’s future did not impede a ceremony in which many of the principal writings of the latter-day restoration were preserved in a large metal box. Modern-day scriptures, translations, hymnbooks, papers, journals, Deseret gold coins, and two books of poetry were selected for preservation. The inclusion of the books of poetry—including Eliza R. Snow’s recently arrived Poems: Religious, Historical, and Political, published by the Church in Great Britain in similar fashion to Lyon’s 1853 volume, and Lyon’s Harp of Zion—was proof that Church authorities saw great value in preserving an artistic as well as a spiritual heritage (Journal History, August 13, 1857). Lyon’s friend, Church architect Truman O. Angell, participated in the ceremony only to see the entire foundation of the proposed building covered over and the future of the temple held in abeyance.

Johnston’s Army was coming, and the sought-for security of the mountain valleys was seriously threatened. Lyon participated with Brigham when the “brethren going into the mountains” received their endowments (Journal History, February 9, 1858). Lyon then packed up Endowment House records and, under the direction of his bishop, John Sharp {Twentieth Ward History 56), oversaw their removal to Provo. He placed his own life at the disposition of the Church. Caroline had given birth to their first child on November 23, 1857; she and Lyon named him Joseph “Young Lyon, honoring the two latter-day prophets. In May of 1858, Caroline took the infant and with Janet and Janet’s two unmarried children departed, moving sadly south—Salt Lake would be abandoned when the army came. Lyon sent two loads of breadstuffs and other necessary articles of domestic use with the families. He compared the Mormons’ departure from Salt Lake with the tragedy of the Saints’ leaving Nauvoo only twelve years earlier. On May 10, 1858, he wrote a long letter to his married children in New York, detailing the sombre events of the move south as well as his melancholy feelings; the letter later appeared in the Millennial Star. He told Thomas and George that he and the family were “all well and enjoying health and happiness, and joy and peace in our most unpopular religion,” continuing,

The last time that I wrote to you, I was warranted by circumstances to urge you to come here at the first opening of emigration, and I fully anticipated seeing you before many months; but now, my sons, my hopes for the present are blasted. When I may have the privilege of seeing you in the flesh is beyond my ken; and what is worse, I see no basis from which comforting hope may spring. I have every confidence in your integrity before the Lord, and feel that, with me, you will bear the dispensations of Providence for perfecting us in the school of adversity and experience without a murmur.

Lyon also sized up the political motives for the army’s presence in and the Church’s withdrawal from northern Utah as well as his reaction to the newly appointed governor:

We have in the city, at present, Governor Cumming, who was sent out by President Buchanan to act as Governor of Utah. He is residing, for the time being, with your brother-in-law [William C. Staines], whose splendid mansion, beautiful garden, and, above all, his well plenished and elegantly furnished rooms, and otherwise tasteful and agreeable accommodations, have been made the home of his Excellency, during his visit to this far-famed, notorious city. I have been in the gentleman’s company, and, from my physiological knowledge of the outward man, I would say that he is, in appearance, a very social, good-natured-looking gentleman—a good specimen of an old country aristocrat, at ease in himself and at peace with all the world; although his coming here with a great army appears rather ominous of a contrary character. However, he speaks well of this people, and he could not do otherwise; but, as there are so very few in the Gentile world who can do this, I must give him credit for speaking the truth. Oh that he had been sent here, with honourable associates, to discharge the duties of federal officers, without that scourge and calamity for any people—the army! The misery that I have witnessed and that only at the commencement of our pilgrimage, would have been unknown. Many a heavy heart to-day would still have been light and merry; many a little innocent that has been out exposed to drenching rain in its mother’s arms, these last few weeks, would have been at home, nursed and watched over with that affection a tender mother can give and their helplessness demands. But oh, my sons, I must refrain from picturing to your mind what has almost broken my own heart. . . .

Some may say we have brought the misery upon ourselves, by refusing to accept a new Governor. This is unqualifiedly false. We prefer President Young to any living man, and have done our utmost to have him re-appointed; but had Mr. Cumming, or any other man of his character, been appointed, without the army accompaniment, we would have received him. I know what I say to be just as true as it is true that we have received him respectfully and courteously into our midst now. It was only yesterday that what President Young said on that subject was the topic of conversation in a small select company, of which I was one. Five out of the six heard him the time he is said to have spoken about being Governor as long as the Lord would have it so, in spite of the opposition of men; and all heard him the second time make allusion to it, on the return of our delegate from Congress.

The final destination for the displaced Saints was still unknown; it could have been as far south as Sonora, Mexico. Faithful Saints deposited full trust in the Lord’s prophet:

You possibly might have preferred to hear of our movements; but I count on your learning of these from Col. Kane. Where we are going is undecided. The people are content to go where the Presidency direct. If the Government show no spark of humanity and disposition to do us justice, it is not unlikely that we will go to a warmer climate; but if Gov. Cumming, and Col. Kane, and other honourable men can be heard, and can be credited, on what they report from actual observation, and from the report of the former on the falsity of the charges of our enemies, which has caused this trouble, we may remain in the Territory. Meantime, the northern settlements will be vacated almost entirely. Trustees remain to manage and dispose of the property as they may be directed.

Yet it is the family and personal messages that most poignantly capture the spirit of the 1858 exodus:

Of my sacrifices to get here, you know well. My most earnest hope and prayer was to see my family comfortably around me and your mother in our declining years. We patiently endured many privations on the way here, and, for the first two years after our arrival, lived very economically, depriving ourselves of many comforts and even necessaries of life, to gather around us something for a home. We got the start, and added daily to that home what we could by honest industry, and often did we sing with the spirit and understanding—

“We’ll plough, and sow, and joyful reap

The land our God has given,

To bless our friends, to bless our foes,

And make our home a heaven.”

But, alas! that labour of years I must leave; that cherished hope of independence, in the evening of life has vanished, and before me is again the wilderness to body and to mind. Where we shall settle we know not; what may befall us is hid from our eyes. . . .

I did not intend to write you these things, but my heart is full, and I could weep over the sufferings of many of my brethren and sisters. Yom sister Lillias has brought me her note to enclose in my letter, and has asked me to read it. Well has she said, “I am afraid to mention our troubles here.” None will feel it keener than she will. She leaves a comfortable home. When your mother and Mary left, and kissed the little ones round, I thought that Lillias would have broken her heart. Her cries were alarming. Possibly a few days together on the road will “drive dull care away”. . .

John is married. Ann lives about two hundred yards from my dwelling, and her little girl is running about, just the picture and figure of herself when at that age; but this cup of joy will soon be dashed from my lips. She, too, wanders, in a few days, from a comfortable home. I truly wish, notwithstanding, that my grandchildren in New “fork were even that near me. Lillias is still as hearty and healthy as she used to be when she tripped the heather hills of auld Scotia. Matthew is a harum-scarum fellow, as wild as a young buck. He has left with your mother’s team. They all remember you and wish you were here to toddle the road with us, that we might bear our wayward fate together. I should very much like to see my daughter Janet. I am glad that the ways of the Gentiles have no attractions for her. She is a good soul—How I love her!—the remembrance of her, when her sparkling hazel eyes used to light up my countenance, the lustre of which shines through the dim distance of many years, in the remembrance of her father. God bless her and all of you, until the time comes when he shall be pleased to gather the scattered remnants of his people. From where, or when you will have another letter from me, I know not; but you may rest assured that, wherever the Church is located, there, I hope, you will find me. (Millennial Star 1858, 483–87)

Church authorities appointed Lyon one of 300 men who were to remain in Salt Lake County and, if necessary, set fire to the area’s buildings and homes. The worried Saints had planted only a few crops in the spring, not wanting to leave foodstuffs to the army and unsure of their future home. In early June, Lyon rode in a wagon to Provo, forty-five miles south, where only a few weeks later, on June 28, 1858, Brigham announced that the crisis was over and that all who wished to return could do so. Within two months 30,000 Mormons trekked back to their northern Utah homes (Arrington 193).

The “Move South” disrupted some but not all of Lyon’s activities. The 37th Quorum had held their last meeting on April 3, 1858, but resumed with a social in the Seventies Hall in October. The large and well-organized Deseret Agricultural and Manufacturing Society, to which Lyon had belonged since the previous year, resumed meetings in July of 1858 and agreed to hold its second annual exhibition in the fall, despite the late and scant harvest due to the exodus. Lyon served on the committee for tanners, saddlers, boot and shoemakers, bookbinders, printers, weavers, and other laborers. Eleven other committees prepared and carried out what the newspaper dubbed the Deseret State Fair, October 4–6, just prior to general conference (Journal History, October 4 and 6, 1858). The committees displayed manufactured goods and some foods produced in the Territory, evidence of productive self-sufficiency in spite of government intrusion. Governor Alfred Cumming and many of the soldiers from Camp Floyd attended the proud show.

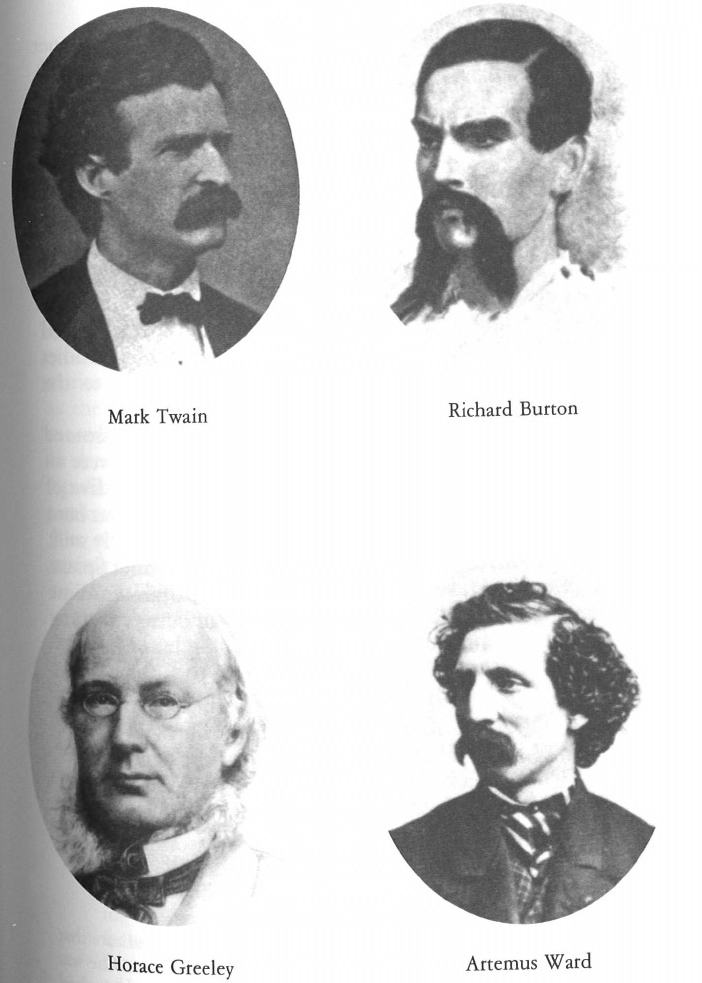

With a non-Mormon governor of Utah many travelers now considered the Territory not only a safe but an intriguing place to visit. Americans from the East, Englishmen, and Frenchmen thronged to the city to record its quaint culture. Because of his daughter’s marriage to unofficial city-host William C. Staines, his position in the territorial library, and his reputation as one of Mormonism’s premier poets, Lyon met most of the visiting dignitaries. On the evening of July 16, 1859, “members, with their ladies” of the Deseret Typographical and Press Association gathered in the Council House to fete Horace Greeley, editor of the influential New York Tribune. Greeley spoke of great advances in printing presses and of the telegraph, which could link continents. Lyon offered one of his original poems for the occasion, “Welcome to Greeley”; no copy of the poem remains. Music and singing continued until 11:00 P.M., at which time the group and its distinguished visitor “repaired to the Globe, where cakes, pies, wines and ice cream were bountifully served up.” The Deseret News correspondent, perhaps Lyon himself, observes that “union and good feelings prevailed throughout, and doubtless in years hence, Mr. Greeley will look back with pleasure on his happy interview with the printers of Great Salt Lake City” (Deseret News, July 20, 1859). Greeley did indeed record the meeting for his paper, but instead of adulation he criticized the apparent jokes made about polygamy and censured the two hours of zealous speeches by members for never once mentioning the evils of slavery, a burning national question for Greeley. He felt that the Valley Tan incorrectly reported some of his casual remarks on women’s rights and later, in a special footnote, clarified his views (Greeley 238, 242–44). Wilford Woodruff, who was present at the meeting, was unimpressed by Greeley, a strong indication that the gathering did not come off as smoothly as the Deseret News had suggested (Woodruff, July 16, 1859). For Lyon the evening was a success; he carried out his customary role as “poet for the occasion.”

Other visitors arrived; the next summer world traveler Richard F. Burton spent nearly a month in the city of the Saints (from August to September I860). He was duly feted and found a cicerone in Lyon’s Scottish friend T. B. H. Stenhouse. Burton gleaned what information an outsider could pick up about the Endowment House, assuring his readers that its secret activities were not sanguine, as others had reported. Then, “being in want of local literature, after vainly ransacking the few bookstalls which the city contains, I went to the Public Library” (Burton 259). Burton there met his compatriot “John Lyon, who is also a poet,” and derived considerable pleasure from the books of the library.

On January 19, 1860, the legislature appointed Lyon territorial librarian; William C. Staines, to whom Lyon had been an assistant for several years, had recently been called on a mission. For sixteen years, beginning in I860, Lyon received $400 a year as librarian, perhaps the first major work he did in Utah for money. Whenever Staines was in town for an extended stretch, he resumed some of the library duties; pay vouchers in the Utah State Archives indicate that Staines received some salary in 1865, 1866, and 1874 (Birkenshaw 11). Lyon, however, was the recognized resident librarian until 1876. As such, Lyon was the Church’s showpiece, a visible symbol of the successful, articulate Britisher, whose presence contradicted claims by Burton, Greeley, and others that Mormon converts were usually of the lower uneducated classes. [5] In I860, the library boasted about 1,000 volumes, “placed in a large room on the north side of the ‘Mountaineer’ office, and the librarian attends every Thursday” (Burton 260). Sir Richard was unaware of, or did not choose to record, the Mormon/

The annual parade of summertime visitors included Orion and Mark Twain (two days in 1861); Artemus Ward (1864); Samuel Bowles, editor of the Springfield (Massachusetts) Republican; Schuyler Colfax, speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives (1865); Charles W. Dilke (1866); and many others. Church leaders arranged for Lyon to meet most of these dignitaries, hoping to impress them with the stature of the man and the books he kept. All of the visitors published hurried comments on the Mormons, on polygamy, and on life in Utah. Twain’s account was one of the more honest ones; through his biting humor he admitted that his brief stay was simply too short for him to make a valid interpretation of “the Mormon question” (Twain 138). Lyon family tradition holds that young Twain and John Lyon met in the territorial library, but no written record of the visit exists. Twain was only twenty-six at the time and had not yet achieved recognized literary stature. Once again Lyon was filling his role as official library greeter and public relations man.

After three years in Scotland and three more waiting in New “Vbrk, John and Janet’s two oldest children began their final preparations for the journey to Utah. Since 1856 Thomas Lyon and George Spiers had worked in New “fork, weaving and setting up a small shop selling imported English china, trying to save money for the trek west. They were ready to leave by 1858, but the Saints’ difficulties with the federal government that year caused another year’s postponement for the two young families. Thomas and Mary Ann now had five young children, the oldest age ten. George and Janet Spiers had four children; their two-year-old had died in New “York in 1858. Just a few days after Janet delivered, the party of eleven rode the train to St. Louis, took a boat to Kaneville, and joined a large company of Saints commanded by Captain Edward Stevensen. The company followed the same wagon route John and Janet had taken six years earlier, arriving in the valley in mid- September (Journal History, September 15, 1859). Among the company members were Lyon’s old friends T. B. H. and Fanny Stenhouse. The reunion of parents and children was warm and long.

During their first winter in Utah, Thomas and George continued the quality weaving they had learned in Europe, while their wives and children crowded in with John, Janet, and Caroline. Just three weeks after his arrival, a report of the third annual Deseret State Fair praised the “silk and cotton fringe by Thomas Lyon” as highly superior to most exhibited (Mountaineer, October 8, 1859). The two young families prospered but apparently never repaid their debts to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund. [6]

Finally, by I860, the lives of John and Janet had assumed a degree of normalcy. Their seven surviving children were all Church members, living with or near their parents; five of them were married. John and Caroline’s second child was born in November of 1859; the parallel families meshed fairly well. Janet frequently lived with her married daughter Janet Spiers, who by 1860 had taken up residence in Tooele, Utah. Caroline kept having babies; the children of the union between young Caroline and John were as follows:

| Child | Birth Date |

| 1. Joseph Young | Nov. 23, 1857 |

| 2. Sarah Elizabeth | Nov. 9, 1859 |

| 3. William Augustus | Dec. 9, 1861 |

| 4. David Ross | Aug. 16, 1864 |

| 5. Alexander | Aug. 17, 1866 |

| 6. James | Aug. 6, 1869 |

| 7. Eliza Snow | Aug. 29, 1872 |

Unlike Lyon’s first family, none of the seven children from the second died in infancy; their average age at death was sixty-two. Eliza Snow Lyon Wilcox died in 1944, making a span of 141 years between her father’s birth and her death!

The census of I860 lists John Lyon, Sr. (he had begun using “senior” since the marriage of his son John in 1855) as territorial librarian with $350 in real estate and $250 in personal wealth (Kearl 1981). While Lyon and his families never achieved a great deal of wealth, they were able to live comfortably on his salary from the library, on commodities received for his work at the Endowment House, on the sale and barter of goods woven from the home loom, and on occasional small payments for dramatic (elocution) lessons and stories and articles published in local papers. Lyon continued as the senior leader of his seventies quorum, but meetings ceased to have the spiritual or intellectual spark of those held in the 1850s. By I860, most were mere business meetings or “public expression” gatherings in which there was no planned topic and in which anyone could speak on whatever he wanted (the minutes of the meetings suggest that they were rather boring). John Jr. and Thomas were both part of the quorum by 1861. All members paid dues, which were generally used as an assessment for the Church Seventies Hall and to provide light and fuel for the meetings. Lyon paid approximately $25 a year in cash dues—the largest annual contribution of any quorum member. He was prospering in Zion; he would return what he could to the Lord.

On August 27, 1859, Hosea Stout, Major S. M. Blair, and a Mr. Ferguson initiated another weekly newspaper in Great Salt Lake City. On that day Stout recorded:

The history of the last week has been the history of a new system of business for me. On Sunday evening last myself Seth M. Blair & James Ferguson conceived the idea of publishing a news paper in this city to be an independent paper so far as religion and politicks are concerned. On Monday we made arraingements with the Editor of the “Deseret News” for use of his press and type. . . . On Saturday we issued 2400 copies of the paper and called it “the Mountaineer.” (Stout 2:701)

Subscription to the new weekly was $6 a year; its motto was “Do what is right, let the consequence follow.” Richard Burton in 1861 observed that it was “considered rather a secular paper” (283–84), yet it likely began as a reaction to the Valley Tan, an anti-Mormon periodical started by Kirk Anderson at Camp Floyd (Campbell 308). The Mountaineer featured more international coverage than the Deseret News or the Tan, as well as full coverage of local court reports. The new weekly took up editorial offices in the Council House, probably with the blessing of Brigham Young and use of the Deseret News press. The Mountaineer was edited in the same room in which the territorial library was located (Burton 260). Here Lyon and the three editors (soon reduced to two when Hosea Stout resigned) frequently traded ideas and information. Lyon recalled his newspaper days in Scotland and likely suggested that the paper publish literary essays and original poetry. Naturally he was able to supply both. During the two years that the paper existed, Lyon published two signed essays, a third under the name “Lambda,” six signed poems, and four under the transparent pen name of “Leo.”

The essays Lyon published in the Mountaineer are vital for their historical insights. “An Essay on Poetry” will be analyzed in the final chapter of this book. The second, “Essay on Physiology and Phrenology” (October 8, 1859), is an extremely well-written examination of a popular belief and practice. Joseph Smith had earlier suggested that the Quorum of the Twelve have their head bumps “read,” likely feeling that the restored gospel encompassed all truth and that phrenology was just one more way of getting at the true nature of human character. In Scotland, Lyon had experimented and even lectured on the subject: “As a ‘private manipulator’ of heads he had acquired some prominence . . . of the so-called science” (Naisbitt 241). Lyon continued “reading” heads during most of the 1850s. On May 6, for example, he interpreted the bumps of seventy-three-year-old John Smith (1781–1854), a curious phenomenon in which a newly arrived European convert told the official Church Patriarch about the latter’s spiritual nature (Smith Diary).