“Of Artists They Have Plenty”

T. Edgar Lyon Jr., John Lyon: The Life of a Pioneer Poet (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 1989), 285–326.

In 1856, Franklin D. Richards expounded one more “must” for Mormon Saints:

It is the duty and privilege of the Saints . . . to procure and study the poetical works of the Church, that their authors may be encouraged and the spirit of poetry [may be] cultivated in the bosoms of the readers by “the thoughts that speak and words that burn” on each page. When man can be taught principle in the beautiful language of poesy, the affections of the heart are purified, the soul aspires to ennobling deeds, and the judgement is better directed in performing them. (Millennial Star 1856, 106)

Now, besides paying tithing, contributing to the Salt Lake Temple, donating to the Perpetual Emigrating Fund, purchasing the Millennial Star, and supporting the traveling elders, Church members were expected to buy “the poetical works of the Church” and then to study them. In 1856, there were only two available volumes by LDS poets: John Lyon’s 1853 Harp of Zion and Eliza R. Snow’s recently printed Poems: Religious, Historical, and Political. Richards’s editorial noted that Lyon’s and Snow’s books were “the pioneer poetical works in the peculiar literature of the Latter-day Saints.” John Lyon was not an 1847 pioneer, but throughout his life he was known as the first Mormon to publish a volume of verse, truly a “pioneer of poesy.”

Yet there were many detractors who doubted the existence of any true poetry among the Mormons. In the 1860s, Richard F. Burton caustically observed that “Art does not at present exist in America, . . . of artists they have plenty, of Art nothing” (205). Burton applied this condemning generalization to all art forms in the United States, including the supposed art and literature of the Mormons. In Great Salt Lake City finding himself “in want of local literature, after vainly ransacking the few bookstalls which the city contains” (Burton 259), Burton concluded that there was little literature to be found. For the sophisticated world traveler, art simply did not exist in America. Lyon and a score of other eager LDS writers, however, were “anxiously engaged” in capturing in poetic form the uniqueness of the Mormon restoration. This uniqueness created a different kind of literature because of the absolute claims Mormonism made about the nature of man and of God as well as its novel beliefs about the universe and historical events of the world. Whether these writers would ever reach the level that Burton would call “Art” is debatable, but they sensed deeply their unique mission to create a special poetry in an extraordinary setting. Lyon and his friend and co-worker in the Endowment House, Eliza R. Snow, were recognized as Mormondom’s premier poets in the nineteenth century and felt the need to capture the spiritual grandeur of the LDS religion in their literature. Lyon’s contributions were continuous and extensive. “John Lyon did a relatively large amount of writing as compared with the output [of other early writers]. . . . One comment will pretty well sum up what might be said about this man and his work: His devotion to the cause was boundless” (Washburn 109–10). This devotion, to literature and the Church, found expression in poetry, fiction, essay, and drama criticism.

Contrary to statements in several early twentieth-century LDS publications, [1] Lyon did not make “his real start as a writer . . . when he was sixteen years of age” (D. R. Lyon 136). Rather, he was at least twenty-six or twenty-seven when he began rhyming words on paper. This late start in an era in which Romantic poets typically began very young, only to “burn themselves out” by age thirty or thirty-five, did not limit Lyon—he still had sixty years in which to write. Some 260 of his poems have been identified; scores of others are lost in the anonymity of early nineteenth-century Scottish newspapers and local anthologies or hidden behind imaginative pen names in the Deseret News and other local journals. (A complete list of Lyon’s known poetry comprises Appendix A; Appendix D notes some of his pen names.)

Lyon wrote much of his early poetry in the Scottish dialect, taking advantage of the unique sounds, diction, word-clipping, and imaginative metaphors of his native land. At least nine of these early poems have been identified:

| Title | Source | Approximate Date of Composition |

| Song of Reform | Songs of a Pioneer 118 | 1833 |

| Auld Man’s Lament | notebook 1 | 1840s |

| Widow Ship’s Lament | notebook 4 | 1840s |

| The Bonny Sweet Heir | manuscript | 1840s |

| O’ the Green Poplar Tree | ||

| “It’s a Cauld Barren Blast That Blaws Nobody Good” | Harp of Zion 121 | 1840s |

| Elegy—On Wee Hughie | Harp of Zion 131 | 1840s |

| Contentment | Harp of Zion 180 | 1850 |

| The Poet’s Farewell | Harp of Zion 217 | 1852 |

These poems, generally free from trite didacticism and the oft-repeated praises of Mormonism found in many of Lyon’s later works, are some of his best. In an examination of early LDS poets, Nile Washburn concludes: “Some of the best selections in the whole study, from a literary point of view, belong to [Lyon’s] Scottish group” (85). The poet’s imaginative language, original imagery, and light tone remind the reader of the early Robert Burns. In an “Auld Man’s Lament,” Lyon nostagically recalls bygone days:

AULD MAN’S LAMENT

The new mill’s a name, which will ever be new

While the dam fills the lade where the water rins through;

Though the miller be dead who first geed it a name,

Still, the din o’ the clapper and happer’s the same.

O weel do I mind o’ the year ninety-three

When we gather’d in crowds ‘neath the muckle ash tree,

When the miller sae bauld, o’er his coggie o’ yill

Tauld his auld forrent jokes ‘bout his mutter and mill.

And aye when the landlady brought a new gang,

There were plenty o’bannocks and cheese or braw whang

To thicken her swats, and put pith in our banes

For the quoting, or curling or putting our stanes.

There the lassies and lads wi’ the auld folks were seen

Joining hands, as they trip’t thro’ the dance on the green;

There was nae proud distinction nor portith ava,

Ilka neighbor was neighbor-like, canty and braw.

When love threw its glamour o’er young hearts sae true

Our gutchers ne’er tried happy love to undo,

Nor sought they to frustrate what heaven had designed

For gold, rank or title ne’er lap in their mind.

When the term day came roun’ there were nae flittens then,

O’ their ain they had a’ a bit, but and a ben;

There were nae growling lairds nor house factors to skrew—

A hame was a hame then, for Scotchmen, I trew.

Frae the Kirkton-holm down tae the foot o’ the glen,

And roun’ by the netherton auld granny en’

There was seldom a quarrel, so weel did they gree—

If a loon dared to wrangle, weel dookit was he.

O there’s nothing like now tae what was lang syne—

E’en the sun in midsummer he cauldly does shine,

And the wee birds sae ourie, they scarce sing ava

Since the miller and a’ my auld friends are awa.

(Notebook, 1849)

The romantic nature of the poem is obvious—past times or lang syne were much better than the present. Lyon chose the year 1793, precisely the time when Robert Burns was in the height of his popularity, as the date for “the good old days.” The setting appears to be Lyon’s own Kilmarnock (Kirton-Holm and Netherton—places near the old town) but is not limited to a single spot—any past time is viewed as more joyous than the present. The poem’s language produces a joyful tone.

A few stanzas from “It’s a Cauld Barren Blast That Blaws Nobody Good” also illustrate the poet’s delight with the Scottish language as well as his concerns for the poor:

When the winter winds roar like to ding down the lum [chimney]

And every fell blast threatens vengeance to come,

Till our biggins o’ thack are left roofless an’ bare,

And the owners half dead wi’ the thoughts o’ repair;

Then the thatcher and tileman may thankfully craw,

While the wind plays old Harry among the old straw,

And tumbles the canes in its hurricane mood:—

“It’s a cauld barren blast that blaws nobody good.”

At the sign of the Bottle, and Three Golden Balls,

Near the Home of the drunkard—the old Prison walls!

There the pimply-faced publican, swelled like a tub,

Wi’ a red partan [lobster] nose, that would blaze wi’ a rub,

And his neighbour, the pawnbroker, live at their ease;

On the last dregs o’ wretchedness, want, and disease,

For them thousands go naked and perish for food—

“It’s a cauld barren blast that blaws nobody good.”

When the state grips the kirk wi’ its cauld, icy claw,

And would force her to yield a’ her rights to the law,

. . . ca’d rebels, and chased from their manses and flock. . . .

Let the chances o’ fate turn the trump o’ the day;

Be it sunshine or murrain, grim want or decay;

Yet there aye will be hope in our losses and fears;

Then a fig for their lectures, their curses, and tears.

While there’s wind in the lift [firmament] let it tear up the thack;

And drunkards to drink there will never be lack;

Should Reformers bawl out till their een start wi’ blood,

“There will aye be a blast to blaw somebody good.”

(Harp of Zion 121)

Expressions like “ding down the lum,” “our biggins o’ thack,” and “till their een start wi’ blood” add to the tone and folksy appeal of the poem. This particular poem takes a swipe at those who drink excessively, at the government, and at the avaricious landowner, but it ends with a positive note: that Reforms will truly bring a brighter day to Scotland. Lyon’s 1833 “Song of Reform,” found in Appendix E, also expresses in similar language concern for the poor and hope for a better future.

In a much lighter vein, Lyon speaks of Wee Hughie, his pet canary, who “spake . . . as weel as some men.” The bird was loved by all; each morning he would

. . . dight his neb on the bauke tapping thing, Then straik down his breast, an’ stretch out his wing, Then ring [wake] up the house wi’ whistling a screed: But he’ll ne’er wake us mair, for Hughie is dead!

(Harp of Zion 131)

The ending of this poem is slightly sad, but its jocund tone and word choice produce little lament. Again, in a fashion very characteristic of Scottish Romanticism, Lyon has selected a minute, homey subject to praise. An incipient humor that infuses much of his poetry in later life is here present. Still the poem seems a little out of place among the serious eulogies of Mormonism that constitute the Harp of Zion.

Several other poems from Harp of Zion, not in the Scottish dialect, were probably written prior to Lyon’s baptism into the Mormon church in 1844. Less than one-third of the Harp of Zion’s 104 poems had been previously published in the Millennial Star. It is not likely that John wrote all remaining (about sixty-five) poems in the book during his busy years as a traveling elder in Kilmarnock nor during his mission in England. The following poems from the Harp of Zion were likely written during the 1830s and early 1840s, before Lyon joined the LDS church:

| Fear | Harp of Zion | 69 |

| Reflections on a Bank Note | Harp of Zion | 71 |

| Recreation (A Fable) | Harp of Zion | 73 |

| Ode to Morn | Harp of Zion | 106 |

| Water—an Ode | Harp of Zion | 108 |

| Time | Harp of Zion | 127 |

The best known of these works is “Reflections on a Bank Note,” published in Kilmarnock and thought by Lyon’s Kilmarnock friends to be his finest poem (Hunter):

REFLECTIONS ON A BANK NOTE

“Money makes the man; the want of it the fellow,

The rest is all but leather and prunello’—Anon.

Thou representative of something great,

What wert thou in thine unconverted state?

Derived from lint, stalks, or, as like may be,

The downy castings of the cotton tree!

Perchance the lowly silkworm’s death-shroud gave

The silky texture which thou seem’st to have;

Spun into yarn—then woven into cloth—

Then worn—then cast away as what we loathe;

And after mingling with—decomposition!

Mark the reverse of this—thy strange transition—

Snatched from the dunghill by the ragman’s hand;

Again remodell’d as thou now dost stand;

Invested with the honour of a name,—

The painted mockery of a righteous claim.

Heaven bless us! and is this our riches!

The loathsome flumm’ry of rags from wretches!

For such as thee I’ve seen life’s forfeit given—

The miser’s soul lose all its hopes of Heaven;

The poor despis’d, and wealthier ones made poor

From failures of thy sponsors—insecure!

Yes, yes, from thee, thou fragment of a shirt!

Or the torn tatters of some mantle’s skirt:

So subject to be lost, consumed by fire,

Dissolv’d with water, or defac’d with mire,

Thy weakly form, how liable to tear,

How soon thou’rt worn, e’en with the greatest care;

But who—vain ghost of currency—pray, who

Gave thee such value, as to stand in lieu

Of labour?—tell me, for I wish to know

Who thy great sponsor is, that I may go

Directly to the source whence thou dost flow,

And there examine what thy motive is

For circulation—ha! interest!! ‘Tis

Individual selfishness makes mankind sweat

To help some lordling of the soil to meet

Extravagance! forsooth, to make his land

(As if it did not yield enough) demand

A double—treble int’rest by the law,

To palm thee, tiny thing! that he may draw

With seeming grace, and usury provoking,

First for his land, and then for paper-broking.

And is this all, vain thing! thou canst produce

To make thee so respected for abuse—

The trust-deed of a promissory pay,

That may go down for ever in one day!

Ha, ha, bank note; when all thy faults are told,

Thou’rt nothing to the yellow, glittering gold!!

Lyon here reduces the worldly honor of the bank note to the “painted mockery of a righteous claim.” In the poem he does not miss a chance to praise the poor and castigate the miserly. The poet humanizes the lowly note, addressing it in familiar speech: “pray, who / Gave thee such value, as to stand in lieu / Of labour?” The poem, in iambic pentameter, is made up mostly of rhymed couplets. Alliteration is frequent; the repetition of the s sound is especially prevalent in the couplet “So subject to be lost, consumed by fire / Dissolv’d with water, or defac’d with mire.” It is as if the repetition of the s helps in the dissolution of the lowly bank note. This dissolution in turn suggests that imagined wealth and paper money are vanity. This implied criticism of government policies was what probably made the poem so popular with Lyon’s Kilmarnock friends.

In addition to personification and alliteration, effective use of imagery is present in Lyon’s early poetry, as evidenced by the first stanza of “Ode of Morn”:

The night! the night! the dark, dull night,

Is gliding fast away;

Sweetly the breath of infant morn,

Wafts on its wings, fair day.

See! see! the rays with pressing might,

Now grey, now blue, now lost in white,

Far, far, o’er hill and sea are borne:

Glad life-inspiring light of morn!

The primary function of this stanza is to paint a descriptive word picture. The desire to teach a lesson or express an emotion is clearly secondary and almost nonexistent here.

After Lyon joined the LDS church, his poetry became decidedly religious and uniquely Mormon. He, with nearly all his fellow LDS poets of the late 1840s and 1850s, placed his poetic ability at the service of his newfound faith. In 1856, Franklin D. Richards reminded Millennial Star readers that Eliza R. Snow’s and John Lyon’s books were

a valuable addition to our literature . . . the two leading works of the kind that are now extant in the Church. They may be considered the pioneer poetical works in the peculiar literature of the Latter-day Saints. We say peculiar, because their writings must be as different from those of the world, as their [LDS] principles and faith. In the great mass now comprising the poetic literature of the day . . . truth is too often sacrificed for fiction, and high and ennobling sentiments for the fantasies of heated imaginations and appeals to passions and feelings belonging rather to the animal than the intellectual part of man. (Millennial Star 1856, 106)

Sensing the spirtual mood of their church, Lyon and other LDS poets often forsook their previous poetic modes or the poetic styles of the day in order to create uniquely LDS poetry. Almost without exception, twentieth-century observers now find this poetry didactic, trite, and “formally and thematically weak.” Cindy Lesser Larsen observes that “one of the problems preventing Mormon poets from creating serious poetry might have been their propensity for taking themselves too seriously” (38, 44). Larsen also mentions dogmatic zeal and high-toned diction as “flaws” in early LDS poetry. From a twentieth-century viewpoint, these accusations may be true, but the faithful nineteenth-century Saints saw no alternative but to merge their will and talents with the needs of the Church. Just as other converts lent their muscles, money, and business and crafting skills to the cause, so too did the believing poets subordinate their style, even their nature, to the “building up of Zion.”

Approximately 70 percent of Lyon’s poetry explores, extols, and animates religious themes. Of the poetry published in the Harp of Zion, the most common theme is to “flee Babylon [the secular world] and gather in Zion”; forty-one poems praise the mythic and actual geographical concept of Zion and caution Saints to depart wicked, soon-to-be-destroyed Babylon. Other religious themes abound: the Second Coming, the need to assist the Lord’s poor, praise of specific Church leaders, the future temple, faith, regret, and obedience. However, Lyon also explores secular ideas that, if properly applied, would make any individual happier and more complete: “Poverty and Debt,” “A Satire on Avarice,” “Lust,” and “Independence” are excellent examples of poems of this bent.

In Songs of a Pioneer, published posthumously, Lyon expresses some of the same religious themes evident in his earlier works. These later poems, written between 1854 and 1885, praise the establishment of Zion, singing of the joys of the new land and of turning the desert into a garden. An amazing optimism pervades much of Lyon’s Utah poetry. While many Church leaders were haranguing the Saints in pulpit-pounding Reformation speeches (1856–58), Lyon was blissfully celebrating the eternal joys of Mormonism, praising the priesthood, lauding the labors of the working class, and even finding meaning in all that Utah offered. The local band harmonized with the hills:

The prairie has no solitude

When music lifts her voice,

The distant mountains echo loud

When Mormon boys rejoice;

The barren waste, the hills, and dales

In rapture clap their hands

Whene’er they hear in Utah’s vales

Our instrumental band

(“Song for a Musical Festival,” Songs of a Pioneer 17)

For Lyon, Utah’s climate and resources were unequaled:

We’ve wealth in our cornfields, the gold mines can’t give; And health in the water, and air breeze to live; Then who would exchange for a king’s palaced dome, With his minions and power, our own peaceful home?

(“Home, Sweet, Sweet Home,” Songs of a Pioneer 18–19)

Happiness followed those who followed Brigham’s admonitions to till the soil:

While reverends sage, with rule and gage,

And politicians great,

Square up the morals and the laws

Of hierarchy and state

We’ll sing of humbler, happier men,

Who live by daily toil—

Who ply the plow-share and the spade

To break the stubborn soil.

(“Farmer’s Song,” Songs of a Pioneer 9)

The quality and value of these lines will be discussed later; here it is sufficient to observe that the recurring theme in these Utah poems is obedience to gospel preaching and sincere joy in the new Zion. These are the prevalent themes in the poetry of John Lyon after 1844 and, indeed, in the lyric expressions of most other nineteenth-century LDS poets. [2] Obviously, there is nothing wrong with exploring spiritual themes—much of the greatest poetry of such authors as Milton, Dante, San Juan de la Cruz, Donne, and Wordsworth has used the religious motif—but early LDS poets generally explored their sacred topics with a dogmatic zeal that often alienates twentieth-century readers. This approach was, nevertheless, the self-imposed mode of the day, the unique themes and style that Mormon poets fashioned for themselves. Lyon was one of the original creators of the style and one of its most prolific producers.

A slight modification in the religious motif in Lyon’s poetry was necessitated by the poems he wrote for special occasions. Of Lyon’s positively identified poems, sixty-three, or approximately 24 percent, were dedicated to a specific person or group. (Appendix B lists the persons to whom Lyon’s poems are “inscribed” or who inspired the verse.) For example, Lyon wrote a poem to welcome Horace Greeley to Great Salt Lake City, another poem to be read as a toast on the Fourth of July, three poems extolling the greatness of the Deseret News press, poems to departing missionary companions, poems to some of his newly baptized converts, poems for an “old folks sociable,” and poems written at the deaths of Brigham Young, W. W. Phelps, George A. Smith, John Smith, a kindly Doctor France, and many others. Lyon was obviously fascinated with the youthful dynamism and spirituality of Franklin D. Richards—he dedicated at least four poems to the young Apostle:

Farewell! beloved of the Lord, farewell—

In Scotland’s name a Scot would dare to tell

How much we’ve prized your labours since you came,

Though now you leave for lands of brighter fame,

Where truth and love—eternal as the spheres—

Shall wield the sceptre through unnumbered years.

Farewell! but oh! one lasting boon I crave,

Remember Scotland, and her sons—so brave.

(“Address [to Elders F. D. and S. W. Richards],” Harp of Zion 17)

Although Lyon wrote many serious poems, a surprising number of his works are humorous. In an age in which the seriousness of their desert-conquering endeavor was foremost in the minds of most Mormon leaders, it is happily suprising to find a poet, truly a public poet in Lyon’s case, who takes delight in plumbing the mines of literary humor. The supposed frivolity of humorous writing had little place among the trekking, building, multiple-marrying Saints (Cracroft 31–37). Perhaps the humor that writers like Mark Twain, Artemus Ward, Arthur Conan Doyle, and other “Gentiles” unearthed in Mormonism caused most’ ‘saintly writers” to retreat to the safe ground of defensive solemnity. E. B. White observes that Americans in general feel that “if a thing is funny it can be presumed to be . . . less than great, because if it were truly great it would be wholly serious” (174). Mormons felt that they were involved in the greatest spiritual endeavor in the history of the world; hence, the wit and whimsy sometimes evident in Mormon sermons and folklore did not often take shape in poetic form. [3] Lyon is a minor if sportive exception to this norm. Some humor is present in such early works as “Elegy—on Wee Hughie” (1840s) and “An Eastern Fable” (1854), but Lyon’s poetry of the 1880s regularly delves deeper into satire, parody, and comic situation than do his earlier verses. By 1880, the attitudes of Church publications and leaders may have permitted more openness with literature, or Lyon may simply have felt more secure in his position and less burdened by convention. Much of his humorous poetry has never been published. A penciled note, “not suitable,” appears by some poems in Lyon’s poetic notebook of the 1880s, presumably written by his serious editor son, David, indicating that these comic poems would not appear in Songs of a Pioneer. [4]

At least twenty (approximately 9 percent) of Lyon’s poems reveal delightful elements of humor. These humorous poems are some of his best—even one of his severest critics admits that Lyon “could have been well remembered as a writer of light verse” (Larsen 44). In these poems, Lyon lightheartedly pokes fun at marriage and polygamy, garrulous women, a federal judge, and others “lifted up in pride,” “model” schools which produce “model” behavior, and pious religious customs; he also parodies poems written by others and even takes a jestful jab at his own avocation, writing poetry. Lyon’s 1854 “An Eastern Fable” has already been discussed. It is a daring poem, an obvious criticism of jealousies in polygamy at a time of great sensitivity shortly after the practice of plural marriage was publicly acknowledged. Thirty years later, after Lyon had personally experienced a plural union, he wrote “Old Age and Dotage,” quite a different poem, discussing the desire of younger, monogamous men to roam about,

While I at home in comfort stay

Enjoying sweet polygamy

O what comfort man derives

From having half a hundred wives!

Using fewer feet per line (iambic tetrameter rather than pentameter) and the unusual rhyme—’stay” and “polygamy’—is entirely appropriate to the light tone of this poem. Indeed, marriage serves as the focal point of the humor in at least six poems as Lyon jests about overly chatty women or cuckolded men (“Meg’s Tongue” and “The Henpecked Husband”).

Lyon’s best-known poem finds humor in the inviolable hour of family worship:

FAMILY PRAYER

‘Tis sometimes hard to be devout at prayer,

For devils then will lead our minds astray

By some injected thought, or outward snare,

And turn the current of our thoughts away

From holy things, in spite of all our care,

So artful are they, watching night and day,

To work our ruin, by some hidden guise,

Which, when found out, we heartily despise.

This story’s of a countryman’s devotion,

While praying with his wife and two small sons,

Who of a dog and cat had little notion,

Were winking by the fireside without hoise,

When all at once, by some infernal motion,

Snap growled at Puss, and gave her such a noise,

When she hissed, spitting, jumped from the attack

And fastened claw-deep on the farmer’s back.

The boys laughed loud to see at pray’r such fun,

While father groaned, and swore an oath or two;

The cat kept scratching where she’d safety won

Above the reach of Snap, who growled, and grew

More furious barking as at Puss he run,

Till all the family were in a stew,

Nor could continue longer their devotion

With such unholy feelings and commotion.

“O Lord!” he cried, in accents quite emphatic—

Rather more serious than his praying mood—

But which he’d often done, stung with rheumatic;

His wife, as every loving woman should,

Roared out, “Confound that dog!” in tones erratic,

“And that singed cat that’s always in a feud”;

And rising from the knees, in holy ire

Caught Snap and threw him plump into the fire.

The husband, sorry for his poor burnt dog,

Threw Puss in fury at his angry wife;

And she, to be revenged, commenced to flog

Her little boys, for laughing at the strife—

“Who were,” she said, “like father, the old rogue,

Who never did the square thing in his life.”

So on they went, a town’s talk and their sport,

Until they parted at the probate court.

Such is a picture I have seen of late,

Suggesting quarrels of a family kind,

That led to greater, and a sadder fate,

To say and do things in our passion blind

Which, when with other, meaner acts combined,

Led on by folly, in an angry state,

To sober thought, and helpless do fail

To calmly act, as we would read this tale. [5]

The poem is very well ordered: presented in the abstract, the first stanza discourses on the problem of maintaining spirituality when the mundane world creeps in. The next four stanzas recount the story of the farmer and his family’s feud, which ends in divorce. Like the first, the final stanza returns to the abstract and offers a moral commentary on the incident; neither the first nor the last directly conveys any sense of humor. The laughable part of the poem comes through the word picture of a devout family trying to effect a spiritual moment. Taken at face value, the poem is a tragedy—a family breaks up over a minor squabble. Humor arises in the mind of the reader not merely from the comic incidents of the four central stanzas but also from the common bond the incident may create with the reader’s own experience in family devotion. As Lyon’s fellow-countryman Robert Burns observes, “The best laid schemes o’ mice and men gang aft a-glee”; and when they do, Lyon suggests laughter as an apt response, even for a pious Mormon father.

Two earlier drafts of this poem contain some important differences from the published version. Lyon originally titled it “Hodge, the Revivalist,” focusing on a farmer who had gone to a spiritualist meeting. Imbued with newfound religiosity, he returned to impart his spirit to his uninitiated family, at which time the parallel cat-and-dog, husband-and-wife incident transpired. The fact that such a thing should occur on “the first eve of his religious life” is, of course, good comic irony. A few lines of these earlier versions even make the poem sound Mormon: “When circumstances come . . . to marr our plans, while aiming at perfection” and “Now he believed [he] was saved, and would increase / In working out his family’s salvation” (emphasis added). [6] These references disappear in the published version, very likely a self-protective move of the author, similar to his attitude in “An Eastern Fable”—a way to keep from running afoul of ecclesiastical authorities who felt the need to avoid levity in matters as serious as family prayer. In the earliest version, after the divorce court, Lyon interrupts the poem and comments that “this moral is not required . . . but lest the description of the picture should be laughed at, and the consequences overlooked, the moral is added.” He then concludes with two lengthy stanzas, only one of which was retained in the poem’s final form. It seems that here, at least, Lyon could not let lightmindedness have the final say.

On the manuscript copy of’ ‘Family Prayer,” Lyon records, “This doggerel sketch was suggested to the author from a chroma [a colored lithograph] in Mr. Savage’s window.” Savage was a well-known photographer of early Utah; Lyon apparently walked by his studio in Salt Lake City and saw a lithograph print that had been touched up and colored. [7] The original painting, model for the chroma, was an oil by American artist Archibald Willard (1836–1918) entitled “Deacon Jones’ Experience,” depicting two children laughing during family prayer. The painting not only sparked the artistic imagination of Lyon but also that of Nathaniel Spens (1836–1902), an early Utah painter whose representation of the main incident (cat on back, dog by fire, family at prayer) is displayed in the Springville (Utah) Museum of Art. Influenced by the title of the painting, Lyon also gave his original version a religious backdrop by making the male character a “revivalist.” The final published version, however, could represent any pious family, even a Mormon one.

Although Lyon wrote several serious epitaphs for departed friends, he also wrote one which is less serious. His “Epitaph on a Fat Sectarian” pokes fun at a pious fellow (obviously not a Mormon):

Here lies beneath this clod—

The frame-work of a man;

When earth was his abode—

A sorry course he ran.

His bumps were very small,

(If brains be thinking matter)

A nut-shell might have held them all;

(The dead we would not flatter.)

But since he’s left this earth,

We hope where ere he’s gone—

He’ll be of greater worth,

Where brains will be unknown.

Ah! what a pity that his wits,

Had not been held within his guts!

(ms)

Rhyming here is not complete but is consistent with the rhyme scheme of some of Lyon’s lighter poems. His diction here approaches the crude but is harmonious with the chubby clod whose pea-sized brain is a more accurate representation of his eternal worth than his paunch. The basic idea of the poem, that intellect is divine and of great worth in the hereafter, is a theme that Lyon, newly converted, preached to his incredulous friends in Kilmarnock in the 1840s. [8] Whether or not the poem chides a real person is unknown.

Lyon was prone to attack and satirize those with whom he disagreed. “The Great Judge McVain” is mordant humor aimed at the federal judgeships in territorial Utah. The poem refers to James B. McKean (pronounced McKane, hence the title’s comic rhyme), a strict federal judge assigned to duty in Utah (Alexander 85–100). A few select verses set the stage:

All the States may have heard of the great Judge McVain—

And the rulings illegal of his soft muddled brain—

The jurors sit dumb when they hear him explain—

How the law does free thieves to go stealing again—

This wonderful judge you may know by his gait—

He walks very stiff with his head quite elate—

Self-esteem rules his brain in one bump of conceit—

(Notebook 3)

Written in ballad form and sung to a popular Scottish ditty “Laird of Cockpen,” “The Great Judge McVain” was circulated among Lyon’s friends and the members of the Twentieth Ward, who no doubt derived perverse comic pleasure from singing it.

Lyon also enjoyed parodying the works of others; the poem, “A Thieving Poet: Dedicated to Sir Pilfery Nibble,” is a 166 line ballad, one of Lyon’s longest and last poems. It is a burlesque of how some work their way to literary fame in Mormon Utah—plagiarize, alter a bit, and publish. Many early Utah journals, editors, and writers fall under Lyon’s parodic pen in this poem: Edward Tullidge, William Dunbar, Charles Penrose, Junius Wells, the Exponent, the Herald, and especially the Tribune (Lyon’s inviolate Deseret News, of course, escapes).

Lyon also parodied several popular poems of the day. “The Beautiful Snow,” by the not-too-well-known American poet John W. Watson (1824–90), was a highly regarded and frequently anthologized poem in the latter half of the nineteenth century, appearing in Fireside Encyclopedia of Poetry (1878), in The Humbler Poets (1885), and in many other anthologies. Lyon, through his work in the territorial library, must have come across the poem in a recently arrived book and found himself at odds with its romantic adulation of beautiful snow. He penned a parody, “The Dreadful Snow” (Songs of a Pioneer 102–04). Watson’s original begins:

Oh! the snow, the beautiful snow,

Filling the sky and earth below!

. . . .

Dancing, flirting, skimming along.

Beautiful snow! it can do no wrong.

Watson continues, praising the snow, wishing he were as pure and even desiring a final “shroud of the beautiful snow.”

Lyon’s poem, of precisely equal length, begins:

O the snow, the dreadful snow!

It comes like a friend, and goes out like a foe;

At first its small flakes come twirling around,

Making farmers feel good, for their seed in the ground.

Till deeper it falls on the pall cover’d earth,

Then he sees all his labor is lost and its worth;

Snow, gathering it falls, and yet softer than down,

While the sun shines thro’ mist with a sickly gray frown.

Lyon traces the storm from small flakes that at first delight the farmer and then turn to heavy drifts, to an avalanche, and finally, to floods that destroy land and crops. The snow completely stymies life:

It blinds and it cramps with a dull, sleepy pain

Till it chills all the body and freezes the brain;

And shrouds you in mist to deaden your woe,

While the wind raves around you wherever you go.

Unfortunately, the poems final stanza (not reproduced here) moralizes on the good life now available in Utah, freed from the woes of winter; this sermonizing weakens the parodic effect of the poem. The innovative, precise images of the first stanzas—“pall cover’d earth,” “the sun shines thro’ mist with a sickly gray frown,” “made homeless and landless without a recall”—all disappear in the final, openly didactic lines. Yet this last stanza is consistent with the original poem it negates and further indicates not only the poet’s need to parody but the Mormon’s need to moralize. The poem is witty but not funny; humor here stems from looking at the world in a whimsical, parodical way. Lyon and his family nearly died from cold and hunger in the winter of 1853–54 but in the more comfortable 1880s could joke about winter weather.

As indicated earlier, most of Lyon’s poetry is a serious eulogy of Utah, Zion, and Mormon ideals. A score of poems, however, many written during the last ten years of his life, enter the realm of the humorous. Unlike his contemporary humorists such as Mark Twain, Lyon was not a master of word play or verbal juxtaposition; instead, he found chuckles in comic situations and characters, in viewing the mirthful side of serious institutions. His humor is rarely belly-splitting but arises from the contemplation of absurdities and inconsistencies in his own and frontier Utah life. [9]

A minor but important trend in Lyon’s prose and poetry is a concern for poetic form and the art of writing. An essay entitled “Poetry”—originally published in the Mountaineer (September 17, 1859) and later amplified and republished in the Contributor (August 1883) and in Songs of a Pioneer—philosophizes on the origin of poetry, its near-sacred place in past societies, and the role of poets in the development of Mormonism. Once again Lyon is full of optimism and views the poet as a noble preserver of truth:

Poetry is not the production of education, but the natural development of expression promoted by the circumstances of life. (265)

Nothing in the shape of literature ever has left or will leave such an indelible impression on the minds of any people of the past, present or future as poetry. (267)

We believe poetry to be the undisguised sentiment of feeling, of truthful perception. (269)

This last quote, almost sounding like one of the Church’s Articles of Faith, equates poetry with truth and faithful perception. At this time (1859), prose fiction was receiving widespread condemnation from Church leaders, who saw it as treacherous and deceptive, especially to women and adolescent readers. Poetry, to the contrary, was “safe,” since it supposedly postulated virtue and truth.

In this essay, Lyon praises Eliza Snow and concludes that most Mormon poems “may be rude when compared with the classical refinement of modern nations; still, they will progress from their present infancy and . . . be more than equal, if not beyond comparison with the most enlightened of any other people on the globe” (268–69). Obviously, Lyon felt that his verse was fulfilling a vital function for God’s people. In his 1852 poem “Epistle—to Liverpool,” Lyon was humble enough to ask the editor of the Millennial Star to read and improve on his poetry which was soon to appear as the Harp of Zion. Lyon also light-heartedly reminded the editor that

We live in days when every fool

His wit would rhyme without a rule,

And pleased in print would show it;

When greater clowns than he would praise

His dogg’rel “chanting billy” lays,

And puff him as a poet.

Lyon was aware of mediocrity, even his own, aware of those who attempted poetry without knowledge of formal rules, and aware of the pride of would-be poets. In his own verse, he strove to avoid these poetic “sins.”

Five poems in Lyon’s collection Songs of a Pioneer also contemplate the role of the writer. In 1855 Lyon penned “Memento to a Talented Writer” (Deseret News, December 26, 1855), a poem lamenting the death of Orson Spencer:

Caught from the altar of our woes—

His burning words can ne’er expire!

Our eyes can see the figured sounds,

The letter’d spirit of his thoughts—

So full of truth, truth that confounds

The mighty in their wisdom caught.

(Songs of a Pioneer 55)

Lyon considered Orson Spencer a great writer, partially because his words “burned with truth,” just as the lyrics of early LDS writers were supposed to have done. The four other Lyon poems that deal with the art of poetry, “Advice to an Amateur Poet,” “Rhyme not Poetry,” “The Spirit of Poetry,” and the humorous “Pen Picture of a Would-be Poet,” reveal the thoughts of a self-conscious writer:

Then what’s poetry, longed for and sought,

. . . .

It’s a gleam of celestial fire,

By the gods to us frail mortals given,

To know and to feel and desire,

And to think in the language of heaven.

(Songs of a Pioneer 33)

And, poking fun at himself, Lyon wryly advises “an amateur poet”:

If you’d correctly write in rhyme,

Make equal feet to sound in time,

For one small word will mar the chime

And spoil the metre,

As want of music is a crime,

But sound is sweeter.

(Songs of a Pioneer 115)

Lyon’s discussions on poetry do not constitute an Ars Poetica for himself or his fellow poets. In them, however, he affirms that serious poetry should be filled with what Franklin D. Richards praised as “‘the thoughts that speak and the words that burn.’. . . When man can be taught in the beautiful language of poesy, the affections of the heart are purified [and] the soul aspires to ennobling deeds” (Millennial Star 1856, 106). What might be designated the “Mormon Style,” especially in terms of theme, took precedence for Lyon over the major poetic movements of the nineteenth century: Romanticism and Realism. Still, the freedom and subjectivity which Romanticism allowed the poet found acceptance among LDS poets, who saw this openness as license to create their own norms for excellence. Given these norms, especially as they were reflected in Lyon’s various observations about the art of poetry, he and most other early Mormon poets saw themselves as being quite successful. The people they most respected—their literate Church leaders—also perceived them as successfully aiding the march of the kingdom and so published their works. Until at least 1868, in the Utah Magazine and later in the Tribune, there was no room for literature of doubt, dissent, or nonconformity.

Still another theme in Lyon’s Utah poetry has its roots in his experiences in Scotland. While toiling as a weaver in Kilmarnock and writing for Scottish newspapers, Lyon frequently praised and championed the rights of the struggling poor and the common laborer. This sincere concern continued in his poetry written while in Utah. He observed that in Deseret the (Lord’s) poor were not demeaned nor forced to beg but always had ennobling work available. His poetry, especially that written shortly after his arrival in the valley, dignifies those who labor with their hands. Various poems, such as “Farmer’s Song,” eulogize printers, railroad workers, sawmill laborers:

While reverends sage, with rule and gage,

And politicians great,

Square up the morals and the laws

Of hierarchy and state,

We’ll sing of humbler, happier men,

Who live by daily toil—

Who ply the plow-share and the spade

To break the stubborn soil.

. . . .

Who is in life so free from strife

Or indigence and woe?

He leads an independent life

That richer men don’t know.

(Songs of a Pioneer 9–10)

A score of similar poems applaud, glorify, and celebrate the life of the common laborer.

The sun shines o’er his lonely path,

The air he breathes is pure,

No cares perplex the woodman’s mind

Which great men’s bliss obscure.

(“The Woodman’s Song,” Songs of a Pioneer 12)

Lyon may have considered himself one whose bliss was obscured by care; he worked a bit in his garden but made his livelihood by his mind and his pen, not by physical labor; consequently, he occasionally expresses envy for the working-class man.

Lyon also observed the work of women, lauded their labors, and even pushed for more equal opportunity for them. In the somewhat unpolished, incomplete poem “Women’s Rights, by Ann Eliza Bel Zebub (Inscribed to Susan B. Anthony),” Lyon argues convincingly that women must be able to extend their talents beyond mere domestic duties. The tone of the poem’s title is jocose, but its message is both serious and timely:

Some men are fitter for the kitchen work

To scrub the floor and clean the forks and knives

Or wash the dishes, fry the eggs and pork

Than we poor slaves, their intellectual wives.

. . . .

And for doctoring who could match our skill

In all the arts of medicine, to cure.

(Notebook 4, 101–03)

Lyon continues the poem by suggesting that women could also excel in the law, bookkeeping, clerking, and other jobs rarely open to women in the nineteenth century. This is one of a very few Lyon poems in which the point of view is not that of a priesthood-bearing male; a woman narrator expresses her deep frustrations with the male-dominated society in which she exists. The fact that Lyon dedicates the poem to women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony and includes the names of Eliza (Snow?) and Bel Zebub (the devil) in the title might make him appear to be critical of the women’s movement. Such is not the case. The poem projects a “better day” for toiling women, but for the present they form a vital part of Lyon’s praiseworthy laboring class. He quite accurately observes in his poetry that they are unable to derive the same pure pleasures from their efforts as working men enjoy.

Numerous other minor themes exist in Lyon’s poetry—praise of Church leaders, especially young, literate and articulate authorities such as Orson Pratt, Franklin D. Richards, and Orson Spencer; poems about his wife Janet (little is said of Caroline, his second wife); the Civil War in the United States; growing old—all these themes remain for future study.

John Lyon was a man who learned to read and write later in life than did most individuals involved with literary concerns. Weighing this fact against the volume of poetry he was able to produce in his lifetime should evoke some respect from his critics and readers even in the twentieth century. Sometimes the formal aspects of Lyon’s poetry are strained, but—remembering his educational background—it is amazing that he was able to try his hand at so many different meters and forms. His poetry may not be great, but much of it is good. It served to teach, persuade, warn, cheer, and uplift the nineteenth-century Latter-day Saints.

Although he was known principally as a poet, Lyon also wrote a great deal of prose—essays, stories, sketches. His earliest works from Kilmarnock have already been detailed; selections from much of his prose are quoted in previous chapters, since many of them are partially autobiographical. Curiously, his prose illuminates more of his life than does his poetry.

Lyon’s earliest story written as a Mormon may be “Paddy’s Unfortunate Journey to Market,” published as an unsigned piece in the Millennial Star, March 1, 1847. The Millennial Star had not previously carried such worldly prose fiction; this piece is an unexpected exception. If it is indeed from Lyon’s pen, he warrants another first. Gean Clark notes that this is “the first actual printing of fiction in a Mormon publication.” Clark believes, however, that it was likely written by a Catholic “because of its many references of Catholicism” (Clark 20). The argument that this unsigned contribution may have come from Lyon’s pen stems from the fact that one of his unpublished poems, “Paddy the Piper,” narrates a similar incident of a simpleminded Irishman who attends the local market in the same town, Baliwach. The poem’s diction, town name, type of character and, of course, simpleminded humor are all quite similar to the parallel elements of the prose story. The parallel name of the main character is also identical, but this may not be a convincing argument since “Paddy” was the name suggested by literary convention for any ingenuous Irishman. If this is indeed a story by John Lyon, it warrants further study—its presence in the Millennial Star is not justified by any religious, moral, or Mormon purpose; it is purely a clever story for the sake of a good story. Interestingly, it appears in the Millennial Star precisely at the time when Lyon was most active in his contributions to the Church publication.

Twenty-seven of Lyon’s short stories have been positively identified (they are listed in Appendix C). Most are not short stories in the modern sense of that genre; they generally lack plot, suspense, character intrigue, and denouement. They are more akin to Romantic character sketches or true-life, nostalgic reminiscences of past incidents. All twenty-seven deal with life in Scotland before John knew Mormonism, yet all were published after he had lived in Utah for many years, and all were published for a Mormon audience. These sketches represented a nostalgic return home for many Scottish and English converts in Utah and so were widely read from the 1860s through the 1880s, during which time they were published in the Deseret News, Tullidge’s Quarterly, the Contributor, the Western Galaxy, and other publications. Many more of Lyon’s stories may exist under pseudonyms or anonymous authorship in Scotland or Utah. [10]

Lyon’s serialized stories began appearing in the Deseret News in 1864 and ran regularly during 1865. Exactly why the paper suddenly began publishing prose stories was never explained to the readers. Then a long hiatus occurred in which the Deseret News published almost no prose. Finally, in the 1880s a revival of interest in Mormon prose again caused Lyon to begin revising and publishing stories and reminiscences from his past life, and various journals sought to publish his writings. Gean Clark has documented the attitudes and speeches of Mormon leaders toward fiction in the last century: “From 1850 to 1888 the sharp battle of words against the corrupting influence which this ‘false’ literature [prose fiction] had upon the minds of the young never ceased” (Clark 4). Church authorities regarded novels and short stories as fiction, a lying literature, while they thought that poetry, as has already been noted, could contain the sublimest of truths, and hence be very acceptable as a teaching/

The taste which is so prevalent in the world at the present time for reading works of fiction, and which is also partaken of by many of the Latter-day Saints, is productive of very great injury.

. . . .

The fascination is so strong—the excitement which an indulgence in this habit produces is so pleasurable, that many entirely overlook the evils consequent thereupon, and they think it an innocent, harmless, yet very agreeable way of passing off their leisure moments. If novels, romances, and works of that character were a true reflection of things as they really exist, though works of fiction, their perusal might not be so hurtful; but the contrary of this is the case, as all who have any experience in the world well know. The counterparts of their heroes and heroines are never to be found in real life; the circumstances their authors place them in, the incidents they depict as happening to them, are unnatural and grossly improbable exaggerations. Correct and tmthful impressions cannot, therefore, be derived from them. They mislead the inexperienced, by giving incorrect views of the world, and produce dissatisfaction in their minds with the circumstances by which they are surrounded.

. . . .

Such books are not only injurious in this respect, but their perusal has a tendency also to impair the memory and weaken the intellectual powers. It is a task of no small magnitude for an habitual novel reader to reflect profoundly or intently upon any subject that requires concentration of thought. The habit of novel reading is adverse to it. It induces superficial reading and thinking, feeds the imagination, gives it undue stimulus and consequent activity; while the larger portion of the intellect, not being called into play, and having no occasion to exercise itself, lies dormant and gradually loses its power. (Millennial Star I860, 110)

In 1871, Emma Fowler warned the girls in the Twentieth Ward “ibung Ladies’ Cooperative Retrenchment Association to avoid the supposed falsity of fiction:

Fiction feeds the imagination and carries us away from real life as it exists and as we shall have to meet it, until realities grow distasteful and we do not relish them. In consequence of this, many grow discontented with the common lot of life and become careless and indifferent. I believe that many a poor woman in the world, has ruined her health by pining and fretting over her supposed hard lot—waiting and watching for something that would never come if she should live to the age of Methuselah—she concludes that life is a miserable mistake and there is nothing worth living for; and all through a disordered imagination produced by novels.

. . . .

Girls, do not say that you cannot give up novel reading. It is worth the trial. I speak from experience. Cultivate the habit of reading, and read books that will instruct and benefit you. They may seem dry at first, but if you will persevere, you will soon learn to like and appreciate them, so much so, that fiction will seem disgusting to you. Instead of wasting precious time on trash, let us devote it to storing our minds with useful knowledge. (58)

Similar attitudes prevailed until the late 1880s, when Church authorities recognized that they could not stop the flood of fiction and so began encouraging local writers to create good Mormon stories. Parry’s Literary Journal and the Western Galaxy were 1880 responses to the need to create special fiction for LDS readers. To provide a substitute for proscribed prose fiction, Lyon and a few other writers had already been filling literary pages with a pseudo-fiction, true-life experiences embellished by the hand and imagination of the author. The fact that fiction was so frowned on may explain why Lyon’s anecdotes lack the literary life of modern short stories—they were incidents taken from real life, true human situations which did not have orderly plots and carefully worked-out character relationships.

On Wednesday, August 17, 1864, when descriptions of distant Civil War battles dominated the first two pages of the Deseret News, a curious new column abruptly appeared on the paper’s third page, “Scraps from the Note Book of an Old Reporter.” It was an unsigned column that told of a reporter’s assignment to travel through Scotland and gather human interest stories for a Kilmarnock newspaper. This reminiscence is Lyon’s first attempt to write creative prose for the Deseret News; during the next year-and-a-half, the lengthy column appeared frequently. Lyon called each of these literary creations “tales,” recounting in them twelve unique incidents in the life of a roving reporter. Together, however, they may be taken as a loosely connected serialized novel, another first in Mormondom, with the reporter (Lyon) serving as the novel’s unifying character. These “tales” were all republished in magazines in the 1880s and some were eventually collected into the stories of Songs of a Pioneer (see Appendix C for a listing of these stories). In these “Scraps” Lyon confronts the Mormon bugaboo of truth in writing and reporting. His Scottish editor attacks Lyon’s matter-of-fact prose: “‘Mr. King [Lyon’s supposed pen name], we shall have . . . none of your wishy-washy trash, nothing but real genuine elocuence . . . Words that breathe, and thoughts that burn’” (Deseret News, September 7, 1864). “Truth must be clothed in ornaments of gaudy attire. . . . [Place] your scraps in a form worthy of being read” (Deseret News, November 23, 1864). Lyon replies,

“This sir,” said I, “would come under the name of novel writing, or perhaps worse, fiction, or—’ “Romance,” he grinned. . . . “King,” said he, “I am of the opinion that your dry narratives would take better if illustrated in character. This tale which I hold in my hand, is well narrated, but if you could put a tongue into your characters and make them speak, how much better would it be.” (Deseret News, June 7, 1865)

Lyon took the editor’s advice and wrote the narrative “Dumida, or the Hermit [‘Fugitive,’ in later published versions] of Colzean.” Lyon said in 1865 that this was his first story and that it was “thirty years in manuscript,” indicating that he first wrote it in about 1835 although the story was never published in Scotland. Lyon assures his Salt Lake readers that he does not embellish the truth, yet “Dumida,” in true Romantic fashion, narrates the story of a taciturn old hermit who lives in the shadowy ruins of an old Scottish castle and who views himself as a tragic victim of circumstances. The tale’s description of place and character reveals Lyon’s mastery of literary language:

Among the numerous little hills, which form that part of Scodand lying west between Colzean Casde and Brown Carrick, may be seen the ruins of an old castle and monastery. . . .

In this sequestered spot there once lived an obscure character, known only by the fishermen and a few visitors who frequented this place during the summer season, for fishing and game. His outward man had little of an inviting appearance, and his distant demeanor deterred even the curious to approach on his company or enter his stronghold. Strange and varied were the reports in circulation throughout the country respecting him. And although the prying eye of inquisitiveness had marked his wanderings by night and day, on hill and shore, still no clue could be distinctly made out as to how he subsisted, where he came from and what were his intentions in living in such a solitary situation.

From the first of his being known by the few persons who lived near the shore, his habiliments or apparel were the same—over his head slouched an old glazed south-wester, covering the tops of his shoulders; a Spanish blue frock coat, the skirts of which met his knees, and lapped his body like a mantle; while underneath might be seen his weather-beaten legs and naked feet, as he paced the beach, or glided across the path of some rustic neighbor returning from a late carousal by the harvest moon. (Songs of a Pioneer 325, 326)

The story is approximately 15,000 words, almost a short novelette. It took five weeks and thirty columns of the Deseret News to complete the ambitious publication. As Lyon’s first attempt at prose fiction, it deserves further analysis. It likely caught the attention of Scottish converts in Utah, anxious to recall the stories of intrigue and adventure from their homeland. The story’s descriptions of place and character are similar to the descriptions written by Robert Louis Stevenson, especially those in the beginning of Treasure Island.

The central conflict of most of the tales in “Scraps from the Note Book” is the continuous clash between reporter and editor, struggles that Lyon undoubtedly experienced in Kilmarnock during the 1830s and 1840s. Thirteen of these twenty-seven somewhat autobiographical stories have never been published. Lyon apparently took his editor’s advice to emphasize character—nearly all of the stories revolve around eccentric individuals with whom John became acquainted before 1844. One of the most intriguing stories recounts Lyon’s search for and successful discovery of a “lost” poem of Robert Burns; another deals with a “resurrectionist” who dug up recently buried bodies to sell to medical students; still another details the comic tragedy of an enthusiastic but failed poet. Character interaction and plot involvement are weak in nearly every tale, but character description is generally innovative and artistic. An example of excellent character delineation is the description of a would-be poet, Tim Snissel:

Tim had an antique physical development; he measured five feet one inch in his shoes, which did not deteriorate from his real height—being heelless. His head was precociously large and symmetrically developed, and when seen over a half door, or through a trap-opening in a pawnbrokers’ receiving room, he looked well enough. There his precocious expansive forehead, his finely arched brow, and blue eye, acquiline nose and fair broad chin, gave a favorable impression of the half seen author; but when viewed in full portrait, he looked for all the world like an inverted V, with a great primer period stuck on the upper point of the reversed letter,—as a termination to its malformation, resembling very much the colossus at Rhodes in miniature. (Songs of a Pioneer 211)

In another story Lyon describes one of his feisty editors as

a tall, thin, meagre-looking personage, of a hard iron-gray complexion, bordering on fifty. His face was naturally long and narrow; his eyes protruded considerably, being very large, the color of which changed so often that I could not say of what they were composed; when he smiled they were yellow; when serious, green; when reflective, a dark hazel, such as I have seen in a cat. His nose was a masterpiece of Roman antiquity, rising in the centre like a drawbridge between his brow, and curved chin, which gutted out and upwards, leaving a small space, to the deep furrow of his mouth, which marked a cut three-quarters across the hollow cheek of his carnivorous visage. His dress, a long, calico-printed gown, considerably besmeared with ink, much faded from its original color, and hanging slovenly on his body. (Songs of a Pioneer 288–89)

With respect to character delineation and narrative description, Lyon may have been a better prose writer than a poet. Yet his stories lack suspense and cleverness. In one story an editor praises the reporter as “a good relator of local incidents,” but Lyon recognizes his own lack of invention and imagination in creative literature (“Jinks and Bellows,” Songs of a Pioneer 290, 305). Curiously, there appears to be more imaginative creativity in Lyon’s pre-Mormon writing than in that written after 1844. Once a member of the LDS church, he generally subordinated his talents to the desirable and soul-satisfying ideals he found in the “new life.” He never wrote prose pieces about his life in Utah, perhaps feeling that they would be too familiar to the experience of his readers. It is a shame that he did not record some of the unique Mormon acquaintances—Brigham Young, Hosea Stout, Christopher Arthur, William Staines, Edwin Woolley—that he knew in Salt Lake City. He could have written of crossing the plains, of trying to harmonize friends and church commitments with the Godbeites, of the “Move South.” Apparently, these experiences were historically and geographically too immediate to enter into his concept of prose fiction.

In the mid-1800s, John Lyon was not the only Scottish immigrant writing LDS poetry and prose. Scottish historian Frederick Buchanan has described poetry by Scottish converts, starting as early as 1841, found in journals and scattered periodicals. [11] Robert Burns’s influence was a constant factor in the production of poetry by nearly any literate Scotsman. The myth that Burns was a simple child of nature devoid of formal education, a rustic who produced song from his untrained soul and native soil, caused hundreds of other compatriots to put down feelings in rhyme. Andrew Sproul, Matthew Rowan, Richard Ballantyne, John Duncan, Mary Bathgate, and scores of other nineteenth-century converts pursued the poetic muse, trying to capture the gospel in verse (37–43). Through friendships stemming from the intellectual, predominantly British Twentieth Ward, Lyon knew and associated with most of these Scottish converts. Few ever did more than dabble in the art, but many felt the need to rhyme words. They looked to Lyon as their mentor.

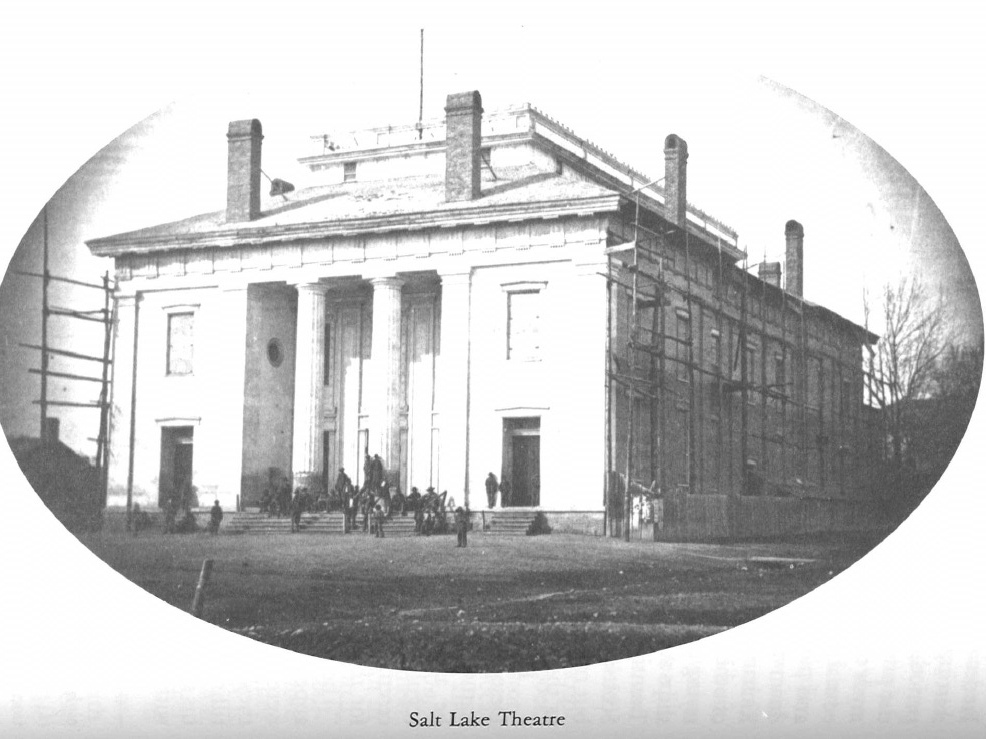

In early 1854, Lyon had linked his artistic life with the Deseret Dramatic Association, where he was immediately named the organization’s official “critic.” In this capacity he assisted in the selection of plays, coached the actors, regularly attended rehearsals, participated in opening night ceremonies, and, most importantly, wrote a review of each play for the Deseret News. Lyon’s columns in the News, titled “The Theatre,” “Theatricals,” or “Theatrical Critique,” appeared frequently during the 1850s, 1860s, and 1870s. They were usually more of a summary of the presentation than they were an in-depth analysis of the performance. Lyon was filling his mixed duty to both the dramatic association and his newspaper colleagues, and so he tried to walk a fine line, without offending either party. In 1863 he wrote:

Like Mormonism and the Mormons, criticism and the critic are not so repulsive as some ignorantly imagine. They have a low conception who take criticism as synonymous with fault finding. . . . The spirit of true criticism leads to admiration of the excellent, rather than to wallow in the mire of others’ defects.

He quickly adds, however:

Yet it must not be supposed that the critic should sing eternal songs of glorification and meaningless praise. (Deseret News, January 21, 1863)

Lyon occasionally made negative evaluations of acting and staging—“Mr. McKenzie, [usually] one of our best actors, was less happy” (Deseret News, January 21, 1863); “Mr. Simmons . . . has defects, and they are mostly seen in his stage action, and in the delivery of his speeches” (Deseret News, February 11, 1863). Most of Lyon’s comments, however, consisted of praise and positive hyperbole. He often ignored writing about poor performances which, by their absence of review, would be obvious. While reporting on a number of dramatic presentations put on in the newly completed Salt Lake Theatre during the week of April conference, 1863, Lyon noted that the plays were “equal in quality and variety to first class general entertainments given either in the States or Europe,” and he later called the productions “[not] second to any similar entertainment anywhere” (Deseret News, April 22, 1863). When an actress or actor that Lyon admired did not perform well, Lyon would often excuse the result by stating that she/

This type of noncritical praise bothered some, among them being Edward W. Tullidge and his British associates Harrison and Godbe. On May 27, 1863, Tullidge wrote a rambling article for the News entitled “Alpha in the Dumps” (Alpha was one of the pen names Lyon used). In the article Tullidge maintains that Alpha (Lyon) is “in the dumps,” that he is depressed because the theatre season is closed, many of the actors are “off to the sunny grape-growing south,” there is “nothing juicy in the city to make the recess a little jolly,” and he (Lyon) has no one to eulogize. Tullidge acknowledges that Lyon “has strong instincts for criticism,” but argues that he is simply too “much disposed to praise.” Tullidge also implies that Lyon is also overly fond of Mrs. L. Gibson, that he takes personal offense when his contributions to the News are edited, and that in future issues, he, Tullidge will reveal much more. The whole article is written with sarcasm but with apparent good humor. The following week, in a short article entitled “A Literary War Imminent,” a characteristic dose of serious humor by Lyon warns Tullidge to be cautious:

Our “devil” and one or two other lads in the NEWS office who recently occupied that “distinguished” position have become displeased with “Alpha,” in consequence of some of his allusions which, they fancy, savor a little too much of personality. They also think that some of his words . . . have not much music in them when formed into sentences. These youngsters having a taste for literature and a superficial knowledge of the science of language, but not having quaffed sufficiently to make them as sober as they ought to, . . . threaten to give the chief of critics . . . a philological castigation. (Deseret News, June 3, 1863)

The literary “war” ended amicably enough, but Harrison and Tullidge’s Peep O’Day cropped up shortly thereafter (1864), an early indication of their estrangement with the established institutions of Salt Lake. Lyon, on the other hand, continued training actors, rehearsing, and writing about the theatre for the Deseret News for more than twenty-five years. Lyon’s full contributions to drama in Salt Lake have yet to be documented.

He also used the pages of the Deseret News and those of the short-lived Peep O’Day to instruct his sometimes unprepared Mormon audience on the history of the theatre, the background of important playwrights, and the role of theatre in the fine arts. And he derided those who did not practice proper theatre etiquette:

There was a good house on Wednesday evening last, with a strong penchant for arriving late and decided moving proclivities when in the building. The music of creaking boots and heavy “stumps” may be agreeable to the owners, but those who are seated would prefer listening to the play. (Deseret News, August 10, 1864)

During the same week in August 1864, Hamlet was presented in Salt Lake for the first time; Lyon not only reviewed the acting and stage setting, he also felt obliged to tell theatergoers how to better understand and enjoy the performance.

Most contributions for the theatre section of the Deseret News were not signed; yet, during the mid-1860s Lyon, as previously noted, frequently used the pen name “Alpha.” The practice of pen names and anonymous contributions of literary material was as common in early Utah as it was in Great Britain. Historian Davis Bitton has recorded 175 pseudonyms, initials, or pen names used to veil the identities of nineteenth-century Mormon writers. [12] Many authors, including Susa Young Gates, Lula Greene Richards, and Eliza R. Snow, used various code names to sign their works. Some identifiers such as W. S. G. for William S. Godbe were fairly transparent, but Dr. Snuffbottle, Kishkuman, Veritas, UnoHoo, Geranium, and Pocahontas are all masks for unknown Mormons authors. Women, much more than men, were prone to write under pseudonyms and invent multiple names; Eliza R. Snow, for example, used at least ten different pen names.

In the pages of the Mountaineer, Peep O’ Day, and the Deseret News, Lyon used at least five identifiable pseudonyms: Alpha, Leo, Lambda, L, and Maggy. These names have been corroborated by internal sleuthing in the poem or article itself or by corrobating manuscripts of the same poem in Lyon’s handwriting. Leo (a lion), Lambda (the name of the Greek letter for L), and the letter L are all obvious and little-concealed uses of a nom de plume. Lyon had used Alpha for some of his writings in Scotland and apparently brought the name with him to Utah; he only signed with it when authoring theatrical critiques or essays. Why Lyon chose to use Maggy is a mystery. He used it only once, in the Mountaineer, May 25, 1861. While in Utah, Lyon wrote of having used “Forest King” (Lyon—king of the forest) in his Scottish newspaper writing; this statement obscures even further Lyon’s literary identity, since I can find no prose or poetry in Kilmarnock or Salt Lake newspapers signed by a Forest King.

It is possible, of course, that Lyon also used other pseudonyms in Utah in addition to the ones I have mentioned. A theatre article in the Deseret News signed by Omega sounds very much as if it were written by Lyon—the possibility that he would have signed himself as both Alpha and Omega, however, is somewhat dubious, as such an act would have been pretentious, even sacrilegious. An 1863 Deseret News column signed simply J is likely from John Lyon’s hand. Iota, Sirius, Diogenes, Philalethas, and Orion are also unidentified pen names used in Mormon journals, some of which could have been Lyon, as suggested by an analysis of the works’ subject matter and types of poetry (see Appendix D). Orion (the hunter—Lyon) was a prolific writer for the Mountaineer, his themes of spiritual and self-renewal ring of Lyon’s ideas. Much of Lyon’s poetry is still lost in unknown pseudonyms and unsigned literary compositions.

Richard F. Burton was only partially right. Time has shown that there were excellent artists and writers in nineteenth-century America. Not only the young United States but also its new religion, Mormonism, could honestly be proud of its incipient literature. The LDS church authorities encouraged aesthetic expression, affirming that the Church would soon have its Shakespeares and Miltons. In the desire to foster local talent, zeal often overcame critical judgment and the spiritual content of a work was prized more than its formal perfection, originality of imagery, or profundity of meaning. John Lyon, however, in a few poems and prose sketches, created striking images such as “bitterness had grown to putrid cancer in his soul” (“The Apostate”), wrote with adequate formal control (the sonnet “Lust,” for example), and offered meaningful insights into the Church, the Zion of Utah, and life itself. In these areas he passed the bounds that a dynamic but sometimes dogmatic religion might suggest for its orthodox poets.

Lyon must be recalled for his “firsts” in LDS literature. The tale “Paddy’s Unfortunate Journey to Market” (Millennial Star, March 1, 1847), if indeed from his pen, was the first short story published by a Mormon in a Church magazine. His 1853 Harp of Zion was the first book of poetry published by the Church, and with the exception of verses published by Parley P. Pratt, was the first published volume of LDS poems. During Lyon’s thirty-six years in Utah Territory, he basked in the renown of being Mormonism’s premier poet. He wrote the first theatre reviews for the Deseret Dramatic Association and the Salt Lake Theatre. His prose contributions to the Deseret News in the mid-1860s may even be viewed as an incipient serialized novel in an era in which Church policy officially frowned on the form. “First” does not necessarily mean “best of all the game,” but the pioneering of new literary genres must be acknowledged for its historical place. John Lyon willingly, joyously, filled his role as pioneer, pioneer prose writer, and poet.

Notes

[1] Articles appearing after Lyon’s death in the Juvenile Instructor, the Improvement Era, the Deseret News and the Millennial Star all indicate that he began writing poetry “at a very early age/’ yet no contemporary record confirms these statements, and Lyon himself records that he had almost no formal schooling until he began attending night schools in Kilmarnock, in his mid-twenties.

[2] A notable and refreshing exception is Sara E. “Lizzy” Carmichael. Many of her poems, even the ones dealing with Brigham Young, demonstrate a high degree of emotional control over her subject matter and an attempt to lift art above zeal. Unfortunately her poetic endeavors only lasted a few years (about 1858–68). (See Miriam Brinton Murphy, “Sarah E. Carmichael,” Sister Saints, ed. Vicky Burgess-Olson [Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1978], 415–31.)

[3] Historian Davis Bitton has gathered a delightful collection of humorous anecdotes, jokes, and sermons from the early Deseret News as well as from the LDS Historical Department and has published it as Wit and Whimsey in Mormon History (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974), but he does not deal with the published poetry of John Lyon.

[4] Notebook 4, in my possession; titles reproduced in Appendix A.

[5] The poem has been anthologized in Richard A. Cracroft and Neal E. Lambert’s A Believing People: Literature of the Latter-day Saints (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1974), 167.

[6] These lines are taken from a manuscript copy in my possession.

[7] American author Bret Harte was a friend of the publisher of this lithograph, J. F. Rider. Rider worried that the picture might appear sacrilegious and asked Harte to write a poem on the subject. Harte’s poem, “Deacon Jones’ Experience” accompanied the colored lithograph in its first edition; from Fine Americana, painting number 754, catalogue, 1978. I have not been able to locate the above-described poem by Harte, which was likely never published in his poetic works.

[8] See the comments of John Kelso Hunter in Kilmarnock Standard, April 20, 1895. Lyon explained to Hunter that intellect would be a distinguishing factor in the next life.

[9] A more detailed account is found in my “Feud and Fun: Humor in the Poetry of John Lyon,” Mormon Letters Annual, 1984 (Salt Lake City: Association for Mormon Letters, 1985), 59–76.

[10] Many of the newspapers for which Lyon wrote in Great Britain are not available at the Collindale (England) Library or any other place. To make the issue more complicated, in Scotland Lyon apparently did not use the pen name “Forest King,” as he said he did while writing in Utah. He mentions the titles of several stories, but I have not been able to find the stories themselves. For example, in a brief introduction, “Scraps from the Notebook of an Old Reporter,” in the Deseret News, he says his editor criticized his stories “Margary Flin,” and “The Student,” (June 7, 1865); I have the latter story in manuscript but have not been able to locate the former.

[11] Buchanan gives examples of poetry from 1841 to 1960. He notes eight categories, all of which are present in the poetry of John Lyon: (1) restoration and testimony, (2) farewell and gathering, (3) human relations, (4) social commentary, (5) tribulations, (6) humor, (7) nature, and (8) recollections of Scotand (“Scottish Mormon Immigrants and the Muse: Verses from the Dust,” Mormon Letters Annual, 1984 [Salt Lake City: Association for Mormon Letters, 1985], 36–58).

[12] From an untitled list provided by Davis Bitton, Department of History, University of Utah.