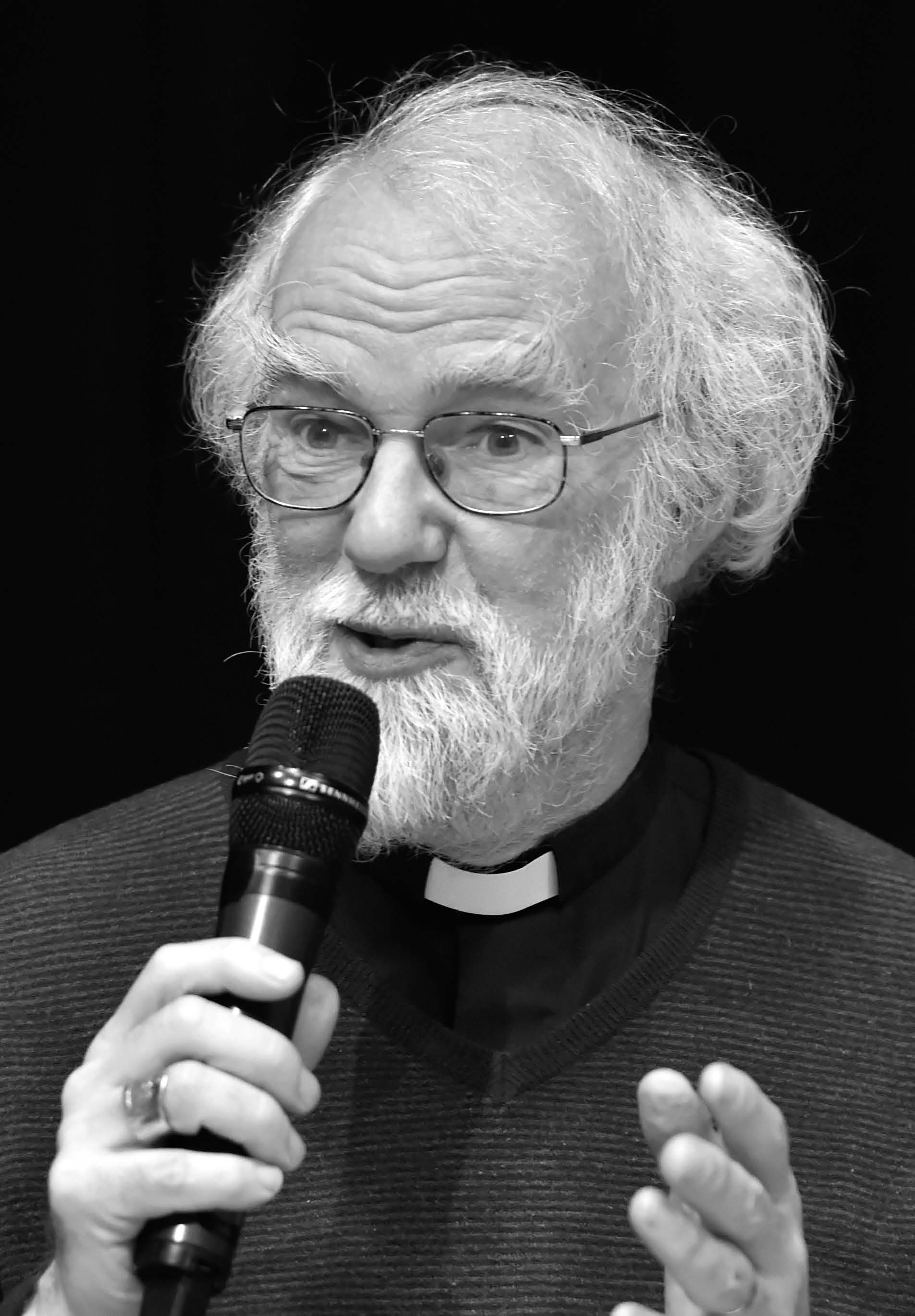

Rowan Williams

Rowan Williams

Rowan Williams, in Inspiring Service, ed. Andrew Teal (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 37–46.

Lord Rowan Williams

Lord Rowan Williams

It’s a very great honor and pleasure to be alongside such a distinguished panel this evening and to have a chance to reflect for a few minutes on what constitutes service and why it’s part of our essential humanity.

Not so very long ago, there died in this country a very remarkable and influential philosopher who was much underrated in the Christian community for many years. Her name was Mary Midgley, and one of the books, which she published about fifteen years ago, was under the title of The Myths We Live By, a powerful collection of essays looking at the various comforting fictions we tell ourselves about our humanity in our current society. She was particularly concerned about the fictions we tell ourselves about the environment we live in and its apparent inexhaustibility. Long before green issues were as prominent as they now are, Mary Midgley was underlining them as issues of greatest moral significance. But also among the myths we live by, she was able to name the pervasive fiction that tells us that the fundamental form of human life is rivalry. Thanks to a particularly unintelligent reading of Charles Darwin, the notion that the survival of the fittest is the law of evolution has taken a powerful hold on the human imagination, especially in the Western world. But the story of evolution is in fact rather different from what that reading might suggest. The more complex carbon-based forms of life become, the more it seems they are interdependent: the more they need one another and the more cooperation, mutual assurance, nourishment, and protection actually come to matter. And to overcome the myth of individual rivalry as the basic form of life, we need a robust account of how advanced life forms, developed life forms, are interdependent.

To put it rather more concretely, we learn and we are fed. The first thing that happens to us as human beings is that we are fed and among the next things that happen to us is that we learn to communicate. We receive before we give. We are what we are quite literally because of what we receive, and in becoming givers ourselves, we fulfill our role within a complex, interdependent form of life. In Christian scripture, this is presented as the optimal form of our life. It is referred to metaphorically as the Body of Christ, in which each agent is given a gift to share with others and each agent needs to receive from others. Whenever you encounter another human subject, the questions you must ask are: What is the gift that they alone can give me, and what is the gift only I can give them? And so it is that the characteristic, distinctive, radical thing about human life is that we are the most complicatedly, sophisticatedly interdependent life-form that there is. To be human is to be inserted into that pattern of giving and receiving wherever we are and whoever we are.

That means, of course, that while we may quite rightly talk about altruism in the sense of putting somebody else’s interests ahead of ours (and I know that Oxford is the home of the effective altruism school of ethics), nonetheless we shouldn’t forget that there is something about our service of others that is quite simply the way we learn to exercise our humanity in its fullness. In other words, the self-interest of wanting to be myself most fully is, paradoxically, interest in learning how I’m most free to serve and to nourish my neighbor.

There’s no great gulf between being selfish and unselfish here. If I want to be myself, that’s how to do it. We get some glimpse of this, don’t we, in those various forms of human activity that are necessarily and irreducibly shared if they’re going to work at all. The devoted and gifted solo violinist who performs devotedly and giftedly as a soloist within an orchestra is not actually doing anything very much for herself or for the orchestra. There’s a famous nineteenth-century novel about undergraduate life in Oxford, by somebody who had no idea at all about Oxford or undergraduate life, that contains a famous description of a boat race with the unforgettable attribution “All rowed fast, but none so fast as stroke.”[1] That’s the problem of individualism. You can’t imagine a boat race without cooperative virtue; you can’t imagine a choir or an orchestra without cooperative virtue. Being good at what you’re doing is being good at the harmonics of that particular group and that shared activity whose goodness, whose excellence is all about how you learn to do it together. Your own excellence has to do with the attention, the careful listening, and the picking up of signals from those around you, enabling them to do what best they can.

So within the optimal human community, life circulates. What’s good for me and what’s good for you are at the end of the day going to be bound together, and one of those myths we live by, a myth which is perhaps unprecedentedly popular at the moment, is that there is some way of literally or metaphorically fencing off what’s good for me so that it is completely irrelevant to what’s good for you. I can keep myself safe and your security or your well-being are of no interest whatever to me.

At the same time as that particular toxic fiction gets a deeper and deeper hold on our world, we’re also, strangely enough, becoming more and more aware of the way in which crises do not stop at borders, the way in which the suffering, the privation, and the challenges of communities on the other side of the globe become our issue very directly. We need as never before, I think, to challenge the inconsistency of a worldview that, in many ways, recognizes more fully our interdependence and an ethic that seems more and more to drift away from the ideas of common good and public service.

David began with three Ps—principles and practice and people. I’d like to add two more to that for discussion and reflection. One is an uncomfortable word—prophecy—uncomfortable because the prophetic tradition in the Jewish-Christian world is about challenging the myths we live by. Prophets in Hebrew scripture are those who above all challenge idolatry and unfaithfulness—that is, the worship of what is not ultimate as if it were ultimate and the betrayal of common virtue and commitment, mutual fidelity, and trustworthiness in society. And we’re talking about service, so I hope we can talk about that prophecy as well: the capacity to challenge this particular fiction of idolatry and to name it for the nonsense it is.

The trouble is, though, that the word prophecy can come to sound a bit melodramatic. There’s a part of most of us that would quite like to be prophetic, to stand up bravely in the public square and denounce manifest evils and then go home again and sleep well. The fact is that, again as David has indicated, and I think Frances will be underlining shortly, effective prophecy, like effective service in general, has a lot to do with the fifth P—prose. It’s not all prophecy and it’s not all poetry. Some of it is slog, boring, prosaic, routine work making tiny, but measurable, difference. And perhaps to phrase our thinking about service within a religious environment allows us to see that prose matters as much as prophecy or poetry; it allows us even to see that failure is not the end of the world.

We might almost add a sixth P—permission. Permission to fail. Permission not to solve everything. Permission not to be God, at the end of the day, which is the most liberating thing that can be said to any human being. We really don’t have to be God because the job is taken. Others have spoken about particular examples and inspirations, and before I sit down, I want to mention one or two of the lives that have stirred and challenged me over the years. Some thirty years ago, my wife and I spent some time in southern Africa working for the Anglican Church there and had the great privilege of meeting a man named Beyers Nordee, a minister of the Dutch Reformed Church who had given up a promising career as a pastor in that church because he could no longer support the Dutch Reformed Church’s attitude to apartheid. He preached a famous sermon in his large and successful church in Pretoria on the text “We Must Obey God Rather Than Man” and walked out of the church, resigning his office. My wife and I met him in very strange circumstances because he was at that moment under what was called a banning order. That is, he wasn’t supposed to meet people, and if he was arranging to meet anybody, there had to be security people present, and he couldn’t meet more than two people at once. So we met him in the lobby of a hotel in Johannesburg and conversed for an hour, which left a very deep mark, and as we parted I felt, as one sometimes does with great people, an urge to say something grateful to him, but I was very tongue-tied (you know how it is), and I found myself saying eventually, “I just need to say how very important you are to some of us.” He smiled and said, “Well, you know, there’s a point where you know they can’t really touch you”—meaning that his integrity was so prosaic, so routine, he just got used to living in the light and didn’t think he was doing anything particularly heroic.

But the second example is, to my mind, a story that tells us a little bit about what the prophetic might mean in certain contemporary circumstances. This is a story of somebody I met in Cambodia, introduced by a mutual friend, a few years ago in Phnom Penh. Scott Niessen, an Australian, had worked for some years in the media in the United States. He’d had some very highly placed jobs managing various projects in and around Hollywood. He serviced the needs and the careers of many quite famous household names and went on holiday one year to Cambodia, where he somehow or other managed to see something of the life of the children abandoned on the streets in Phnom Penh. As you may realize, Cambodia is a country still suffering the colossal trauma of the Khmer Rouge tyranny mentioned by David earlier. Generations were literally wiped out; broken families and parentless children are still a regular feature of life there. Scott spent some time simply getting to know something of the circumstances of the children living on the streets in the city from birth upward. He went back to the States and thought quite a lot about what he ought to do. Niessen went back to Phnom Penh to visit some of these communities in the streets again and to begin to work out what was the best thing that could be offered to them. He likes to tell the story of when he was there, walking through inches-deep sewage in the back streets of Phnom Penh with a couple of naked children clinging to his arms and legs, he had a call on his mobile phone. It was from one of his senior media clients in the United States, who wanted to complain to him that the video games on his private jet were not the ones that he’d ordered.

Scott says that that was the moment at which he realized what kind of human being he wanted to be and what kind of human being he didn’t want to be. He gave up his job, he sold his house, he moved to Phnom Penh, and for the last eight years or so he has been running a charity in Phnom Penh that deals with nearly 1,500 children in the streets there. I had the privilege of spending a day with him, meeting some of the children he works with and seeing some of the work he does with the police in Phnom Penh. He’s managed to persuade the police force in Australia to assist some people to the work in Phnom Penh so that they are able to train police there in safeguarding child protection: how to handle complaints of abuse, violence, and sexual exploitation. In other words, he’s addressing both a personal and a structural set of problems, and he’s one of those people who is very definitely among those who for me defines service and inspires because of that.

And the question that he found himself asking when he had that call on his mobile is the question that service finally prompts: what kind of human being do I want to be, and what kind of human being do I not want to be? Do I actually want to be part of that mutually nourishing humanity in which others goodness actively feeds and enhances mine and my goodness actively feeds and enhances others, or do I want to be committed to a fiction that will, in the end, poison and kill us all? Thank you.

Notes

[1] Compare Desmond Francis Talbot Coke, Sandford of Merton: A Story of Oxford Life (Oxford, 1903), ch. 12, who likewise describes an individual rowing faster than his team: “His blade struck the water a full second before any other: the lad had started well. Nor did he flag as the race wore on. . . . As the boats began to near the winning-post, his oar was dipping into the water nearly twice as often as any other.”