Question and Responses

"Questions and Responses," in Inspiring Service, ed. Andrew Teal (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 55–70.

Teal: Thank you very much indeed for such diverse and inspiring addresses. I would like to sum up tonight by reflecting on who it is that can inspire others. It can seem, particularly with these stellar guests tonight, as if it is only the most articulate and powerful that inspire others, but I think I will share something with you, and I hope to spare someone’s embarrassment.

I remember when I was eighteen years old, I was sitting in a garden at Selly Park in Birmingham. I had prepared food for Arthur, of whom we have just heard, and one of the things he loved to do was throw his food on the floor after I had prepared it. It was a nice afternoon, we sat out in the garden. He was on his beanbag, and he had his rattle. The light was going through the trees and the way in which leaves fluttered made a beautiful pattern, and he was holding his hand out—I am not sure if he still does this?

Young: Yes!

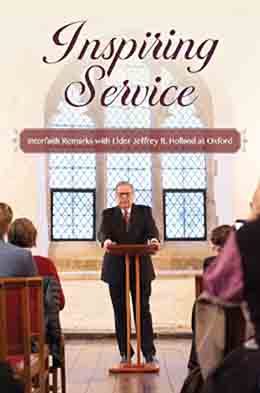

Arthur Young

Arthur Young

Teal: There I was trying to read, trying so hard to read Karl Rahner and thinking, “I’ve had enough.” And I looked at Arthur, and Arthur, without the din of words, in a sense, called me to be who I should be. One of the things about being human is our ability to be called out by another person, who in a sense calls us out into being. And actually that was a moment when I realized I do not need to be Karl Rahner; I do not need to be Frances Young, to do that profoundly. Arthur, by simply being himself and inhabiting who he was, had this immense way of inviting and challenging me to take my path. So thank you, panelists, for sharing your vision and inspiration and for encouraging us to be who we are. Now, there’s time for questions.

Question 1: Thank you so much for such an inspiring group of talks. Lord Alton, you mentioned that democracy without values quickly becomes a thinly disguised totalitarianism, which reminded me a lot of Walter Benjamin’s idea that there is no document of civilization that is not the same as a document of barbarism and Theodor Adorno’s idea that fascism is the aestheticization of politics. Lord Rowan, you also mentioned we need to challenge the inconsistency of our worldview, but Frances Young said we need to protect the nature of institutions. I guess my question would be, how do we as Christians expand our empathic circle not just beyond the nation-state but to outside our species as well? For example, gorillas can speak two thousand words in the wild and can be taught; they have an IQ of 89. So philosophically defined, if not biblically defined, gorillas are persons, right? This example is just to illustrate my questions on how Christianity can help challenge our species’ chauvinism, and what do we have to say about environmental civil disobedience? Could this be a form of service?

Alton: I’ve got the short straw again. I suppose, being at Oxford, I can quote C. S. Lewis, can’t I? He was a member of the anti-vivisection society and once said, “If you start off being cruel to every other species, then you’ll end up being cruel to your own.” [1] Pope Francis writes (in Laudato Si) about the entirety of creation and our duty to be good stewards of what God has given to us or entrusted to us, and I think that there is a real call in your generation, especially. Others in Rome have particularly referred to the way in which we have destroyed so much of what we have been given, and I think we will be held to account for much that we have done.

Your point about institutions is a good one as well because I think it was Thoreau who said that if you cut down all the trees, there’ll be nowhere left for the birds to sing.[2] And it does worry me that we are at the point where so much of our institutional life in this country is under attack. I talk now again about politics for a moment, but we as political classes have a lot to answer for, specifically for what we have done to the institutions that have been entrusted to us. These are fragile things, and they are passed from generation to generation, and my theory is that it is the toxicity, the disconnection that I referred to earlier on, that is leaving people incredibly cynical with the political classes. I chaired one of the biggest meetings as a neutral chairman; I had my own views and cast my vote in the referendum like everyone else, but I was asked to chair a referendum meeting in Lancashire, and what struck me most about it was not how they voted, there was no doubt in my mind about how the people were going to vote (these were people from the Lancashire towns, places like Burnley, Blackburn, and Clitheroe), but it was the anger that was amongst the people there. They were not all racist and xenophobic people lining up behind the English Defense League. They were angry with politics and politicians, and they were going to give us all quite a kicking about the principal question that was going to be on the ballot paper in the referendum. So I think we have brought a lot of this on ourselves by the disassociation we have made with the people who are on the streets. Back in my parliamentary days, but even more so as a local councilor, we called it community politics. People will sometimes dismiss it as playing politics, but being there on the pavement, being there on the street, connecting with ordinary people, I think that there is a huge amount to be done to reclaim the lost ground. Because we do not do that, and there is a lot cynicism about our institutions at this time, whether it is parliament, the Church, the broadcasting media, the law, and I think that’s very dangerous for us.

Holland: In passing the microphone, I will just note that the adage is “think globally but act locally.” The larger the institution, the greater the abstraction. Nevertheless, in the end, institutions are made up of people; they are made up of individuals, so I believe in a variation on that little theme: survey large fields but cultivate small ones. I do not know how else to deal with large institutions except to deal with the individuals in them. We should have what influence we can. Mother Teresa commented, “do what you can,” and that’s usually not at a global level; it is not often at the institutional level. It is usually more private, more personal.

Williams: If I’ve got time for a very brief comment, first of all on gorillas and the like. Yes, I think the same fundamental principle applies: what is securing, nourishing for the environment we are in is bound up with what is secure for us, and the idea that the human race somehow lives six feet above the rest of the organic world is a myth. I think that is a key insight here, and I’m very glad you’ve underlined it so strongly. Which is also why, given the whole ecological picture, I have put my name to support the extinction rebellion in the last couple of weeks. But just very quickly on the word ecology. An ecology is a balanced, interactive system that finds equilibrium by the working of its components. That means that there’s a social ecology as well. Part of a good social ecology is what I like to call sustainable institutions, that is, institutions that do not just wobble around depending on political fashion and electoral cycles. One of the biggest challenges we have is to create and maintain sustainable institutions—that is, institutions that have in view the good that is not just dictated by electoral cycles and political fashion. At the moment, we have been busy tearing up lots of those, or, as David just said, undermining them in various ways. Institutions need to think about how they regain and retain credibility because they have been guilty of betrayals and failures. And, also, I think we need to challenge the climate, the media climate of our society, which is hostile to institutions in problematic ways. So there is a lot, but ecology is the word I am coming back to here.

Young: Have you heard of slime mold? It is a living thing that is just one cell under normal circumstances, but in certain conditions the cells coalesce and you get what they call emergence. I think it was in 2004, that Japanese scientists said they taught slime mold to find the shortest route through a maze even though slime mold has no central nervous system, no brain, nothing. Now, I think that’s a parable of the human race in relation to the planet. Actually one of the things that’s really dangerous is the idea that we are single cells because corporately we do things through these sort of feedback mechanisms, influencing one another to the point where corporately we do things that are profoundly damaging to the very environment that sustains us. I think until we can start thinking through that, we are in a very dangerous place in terms of the future. But it’s OK; I am not going to live much longer, you know. [laughter]

Question 2: My question is for Rowan Williams. I was really interested in your statement that advanced life forms are interdependent, and you think of the length of childhood, for example, where different species and human children are dependent is for an awfully long time. As our world becomes more complex, perhaps that length of time is becoming even longer. So much of the scientific (and not just science but economics, evolutionary biology, and neurosciences) way of studying human nature is really from the point of view of the self. And there is sort of a selfishness in economic conceptions of rationality and the selfish gene, for example, in understanding how evolutionary biology works. It seemed to me in your comments there was a nascent theory of human character of human identity that was quite different than this emphasis on self and selfishness as being the key to understanding biology or human nature, economic relations, and so forth. I was wondering if you could just expand on that a little bit for us—and maybe even not just of human nature but of human ecology because that may tie in to the connectedness humans have to the environment and to other species . . .

Williams: Thank you, I won’t try to give a lecture on the whole theory, you’ll be glad to know. But I think one of the oddities of the last few decades is the eagerness with which people have embraced this mythology that I spoke about. And Richard Dawkins’s selfish gene is not science; it’s a massively inflated metaphor that is not recognized as such. I often like to say to secondary school students doing science, “Remember, there is no such thing as a gene. There’s a little bloke in there.” We talk about genes as a way of talking about the transmission of information, about intelligence. As Frances was hinting, the whole ecology of creation, intelligence, the exchange of information, the feeding of systems into each other, feedback loops, all of that, that is the scientific world we are actually looking at these days—not this world of curious little chaps in armor going around inside us doing what they want, competing, and somehow winning little battles inside us. That’s a bizarre picture, but whether it’s neuroscience, evolutionary biology, or physics, the picture of unexpected, unplanned, and sometimes quite elusive connectedness is what the scientific world seems to be delivering to us now, and theology and philosophy really ought to be catching up with that. It’s not to say that collectivities trump individualism; it’s to say that relationship and intelligence are fundamental categories in the reality we experience. A lot more can be said, but that is where I would start.

Question 3: Everyone mentioned a bit about atomism in society, the breakdown of communities, and in a multicultural society here or anywhere in the western world, how can we work against that if we insist on myths of Judeo-Christian heritage? Rowan talked about prophecy and breaking down idolatry when the prophet who had the most to say about idolatry was Muhammad, and I am really struggling to see how Christianity or Judaism has more to say either in its history or in its philosophy about democracy over Islam. So, if we are living in a multicultural society and we are trying to break down barriers, how can we do that if we hold ourselves as the exemplar of what the right society should be, ourselves being the Christian community?

Young: I think I would come back to what I was saying about meeting the “other.” What we need in our society is more people who reach out and meet the “others” who are different from themselves. It is when you actually receive from people who are different that you offer them dignity and we become a part of a much larger whole. I do not think this can be done from the top down. I think it has to start with ordinary people in ordinary places who actually walk across the road that has become a barrier.

Williams: The last thing I would want to suggest is that somehow this is all about encouraging another round of Christian triumphalism. I am a Christian; I believe the Christian faith to be true; I believe that I can also learn from other religious traditions and that in the face of the kind of secularism that empties out the content from the world around us, we need to listen to one another and work together. So, to me, it is rather important that, as you rightly say, Islam is a tradition at the beginning of which is a rebellion against idolatry and that Buddhism is a tradition at the beginning of which is a rebellion against the idea of a solid, independent self. These are crucial insights that we need to save our world, as you might say. It does not alter the fact that, for me, the Christian faith is the most comprehensive and the most dependable picture of reality that I believe we can have. I will argue that with my Muslim and Buddhist friends ‘till the cows come home. I do not expect them to agree overnight; I do not expect Christianity to be the dominant cultural presence in the world. I am grateful that there are other voices that echo back what I believe is most precious in my own legacy and enhance it in so echoing.

Holland: I don’t think there would ever be a suggestion, certainly not from us and I do not think from any of you, that Christianity, the Judeo-Christian tradition, or the Western world generally has some corner on the market of truth. We will be open to truth wherever it is and from whatever persuasion, whatever culture, whatever religious faith it comes from. That seems to me to be a given for contemporary issues, current social issues in the world in which we live. The advantage starts to come for Christians (as long as we are using that language and that persuasion tonight) and starts to take on its real significance, in another world. It is beyond the contemporary environment, contemporary ecology that the real significance of Christianity and the life of Christ has its greatest meaning. So that takes it to a higher level for me when we talk about the distinctive quality and the unique characteristics of the Judeo-Christian tradition. I would also say there are things that the Judeo-Christian tradition brings to the contemporary world as well as the eternal one. However, not exclusively and not at the expense of others who also so teach. For example, when we talk about ecology, I think Christians could start by talking about the ecology of a marriage, the ecology of a family, the ecology of a neighborhood. If we talk about the environment—the environment of the soul, the environment of the human heart—I think Christianity has a great deal to say. And then if the discussion of the environment goes beyond Christianity out into a wider circle, a wider world, a larger globe, so be it. We will take whatever truth comes in addition to what we have, but there are some unique gifts, there are some unique promises—prophecies, if you will—that come with the Christian tradition that are salvational now and later.

Alton: When I went to Liverpool as a student, we still had a sectarian party on the city council, which was still there when I was first elected to council, and it brought to mind that thirty years earlier the Catholic archbishop and the Anglican bishop would not even say the Lord’s Prayer with one another because they didn’t recognize each other’s orders, and such was the relationship in a sectarian city. What a contrast when after the London bomb, standing on the steps of Liverpool Cathedral were the Anglican bishop, the Catholic archbishop, the local rabbi, the trustee of a local mosque, and the secretary of a Hindu cultural organization holding a sign that said “But not here.” Now it seems to me this is the issue: how do we learn to live alongside one another respectfully? It is not quite saying, well you were more concerned about idolatry than we were, or we have all the answers to everything that confronts us; it is not for those reasons at all. We enter into each other’s lives, and we are enriched by that.

As a student, and I’ll come back to the practical now, I spent two of my vacations thinking I was doing a bit of good because I taught immigrant children English. It did me more good than it probably did them. The children primarily came from Chinese backgrounds, they had come via Hong Kong, but many had escaped from Mao’s China and the Cultural Revolution. Learning their stories was extraordinarily instructive for me. Hearing the suffering and the pain that they had gone through touched me. One of those families became very close friends of mine, and indeed one of the children of that family is my goddaughter. I mentioned her in a speech in Parliament this week in the House of Lords on Monday when I raised the issue of English as a Second Language. How can we have true integration in this country if we don’t even give Syrian refugees and many others who are here living in this country the opportunity to learn our language? ESL courses have been cut by 60 percent over the last ten years. This is a crazy thing to do. It touches on something very fundamental: that is, our identity. I do not need to surrender my identity to enter into other people’s lives. Isaiah said, “Consider the rock from which you were hewn” (Isaiah 51:1, New Jerusalem Bible), and wasn’t it King Croesus of Viridans who went to the oracle and asked, “What is the most important thing a man should know?” And the oracle replied, “Know who you are.” Know who you are. So I am a Christian, but that does not stop me recognizing the gifts that other people bring to the table and learning to live alongside them is crucially important. Next month in December we will commemorate the seventieth anniversary of two things. One is the genocide convention. Hold that in mind when you think about what happened to Yazidis, Christians, Shia Muslims, Jews, Shabaks, Mandeans, and other minorities in northern Iraq and Syria. The other anniversary is the universal declaration of human rights. Article 18 says, “Everyone shall have the right to believe, not to believe, or to change their belief.” It’s honored in the breach all over the world. This is something that brings us together. One million King Croesus of Viridians were sent to reeducation camps in China. Rohingya Muslims were persecuted alongside Christians in Burma. Raif Badawi was humiliated and beaten in Saudi Arabia because he was an atheist, and Alexander Aan spent four years in prison in Indonesia because he posted on his Facebook profile that he didn’t believe in God. We have to stand alongside one another, stop measuring how much we believe in something against how much someone else believes in something, and stop trying to set up mutual rivalries that will take us nowhere.

Geoff O’Donoghue: Good evening and thank you very much. This is partially a question, but maybe more an observation prompted by Mark’s question about where we find this empathic capacity that will be required in our modern world. All this talk about the self, prompted me to reflect on what Pope Francis said about the sacred and reconnecting with the sacred in our lives and in our world. And he spoke about that very explicitly in terms of understanding the sacred in all things, the interconnectedness of all things. But he also made it very clear that this was an ancient knowledge; it was not a new knowledge that was being imparted. For myself, if I go back in my own ancestors, Celtic ancestors, when they sat down to milk a cow, they put their hand on the side of the cow. In that very moment, they gave thanks for the bounty of that moment and for the gift that they were about to receive, and it was that close—their understanding of the sacred, the sacred nature of God and of all things, and the sacred nature of themselves and the animal that they were encountering was all part of a single relationship. And I think this is the call that we have been given again, because of the degree to which we are individually able to reconnect with what is sacred: with our God, however we express that; with the sacred in the person; and with the sacred in every creature. When this happens on the earth, it seems to me that it will prompt service, and it will be the kind of service that heals and is what is needed for this next stage.

Holland: That probably wasn’t a question; it was a major message. That was wonderful. But inherent in that comment, it seems to me, is the reminder that life is noisy, things are busy, there are distractions; there are competing urgencies and demands. As I mentioned earlier in my brief remarks, even the living Son of the living God had to get away, had to retreat, go into the mountains, get away from the crowd, even though He was committed to the crowd and all the purposes and all the needs of that crowd. I think you have given a wonderful statement about the constant need to renew, to look inside, to reflect, to meditate and respond and pray. Only then can we be fortified to reengage and come back for the battle. But we need to remember that at some point that tank of fuel can run out. We need to renew, we need to refortify, until it is there, the holiness is there, the sanctity is there. I believe that if we take the time to get away from the noise, move away from motion, we are better prepared to engage in the substance of what this conversation has been about here tonight.

Williams: I am very glad that you have foregrounded this idea of the sacred because it seems to me that to acknowledge the sacred is to recognize there is something that we absolutely and fundamentally do not own. And the idea that we own, have a right over, or possess something, whether it is the world we are in or another person, is the absolute opposite of anything we could understand as service. So my question, really, is for all of us and for our culture: what are the processes and habits we educate our people in, especially children and young people? Do we give them the opportunity to experience the world as something that is not owned? Other people as realities that are not owned. How do we get that pause, that hesitation, that distance that allows us to see that this is not us, this is not our property? That can be in all sorts of ways, and I do wonder whether our education system at every level really gives those opportunities to young people with the more functionalist, busy, and anxious we get as educators. That’s another story that is with us.

Teal: Geoff O’Donoghue is international director of CAFOD (the Catholic Fund for Overseas Development), and I think he is able to answer any questions tonight if anyone is interested in spending time with that organization.

Thank you so very much to everybody who is here tonight, because it has been an experience of people really wanting to engage and question, and it’s been like watching something alive and kaleidoscopic—changing with illumination and color from different directions, so we have witnessed texture, nuance, and integrity. I do not think I am alone in being absolutely delighted that this evening has gone the way it has and profoundly thankful to our speakers.

Notes

[1] C. S Lewis, “Vivisection,” in C. S. Lewis: Essay Collection and Other Short Pieces (London: Fount, Harper Collins, 2000), 693–97.

[2] See Richard Higgins, “Thoreau and Trees: A Visceral Connection,” 2 June 2016, https://