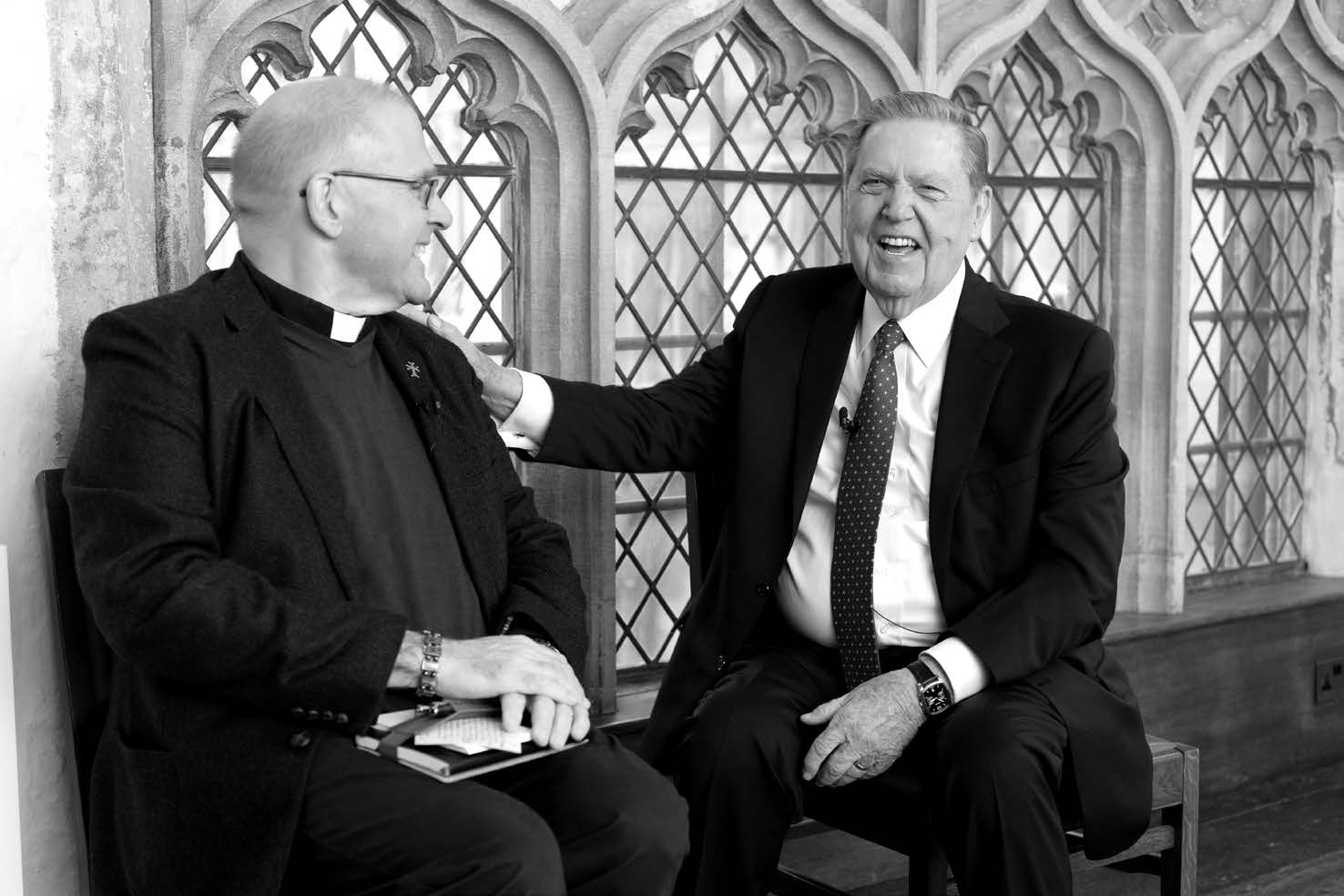

Jeffrey R. Holland with Andrew Teal

Jeffrey R. Holland and Andrew Teal

Jeffrey R. Holland and Andrew Teal, "The Restored Gospel" in Inspiring Service, ed. Andrew Teal (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 73–108.

The following remarks and question and answer session took place at the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin, Oxford, under the auspices of the University of Oxford’s faculty of theology and religion on 22 November 2018.

Reverend Dr. Andrew Teal and Elder Jeffrey R. Holland

Reverend Dr. Andrew Teal and Elder Jeffrey R. Holland

Holland: Thank you, Professor Paul Kerry; we acknowledge your role here at the university and the wonderful relationships you’ve built and the kindness of the Reverend Doctor Andrew Teal, whom we love and admire as a friend. We are grateful for the hospitality that we feel here today.

Andrew has invited me to speak for a few minutes about The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, its doctrine and practice, and then allow some question and answer time. I want to say at the outset that I am anxiously trying not to be off balance here. I realize I am over from the colonies, so that in itself is a little unsettling. The other unsettling thing is that although I know my own theological vocabulary, I nevertheless want to make sure that I honor the language Andrew will use. That leads me to the only humor I will be able to work into this talk, and I hope it is humorous. When doing background work for this lecture, I discovered that the very earliest Anglo-Saxons did not have a concept of eternity. It was then I realized that was how the game of cricket was created. [laughter] If I fall back or fall short, please understand at the outset that I love this country. I have lived here for more than five years of my life and am proud to be the true anglophile in our quorum and in our Church leadership.

I’m anxious to share information with you today that will be more substantial than the clichéd humor that somehow still manages to find its way around regarding polygamy, which we do not practice, or the fact that there are double decker buses this very hour circling Piccadilly Circus and the neighboring theater district in London, pleading for everyone to see The Book of Mormon musical. In contradiction to those buses and those billboards, we would prefer that people read the Book of Mormon rather than see the show, but I suppose we will just let that go as show business does. If all that you know about The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is what you glean from pop culture or street conversation, you probably do neither yourselves nor us the adequate justice that I hope I can summon today.

We believe that we are coming to you and to the world in fulfillment of an ancient prophecy from the gifted prophet Isaiah:

They are drunken, but not with wine; they stagger, but not with strong drink. For the Lord hath poured out upon you the spirit of deep sleep, and hath closed your eyes: the prophets and your rulers, the seers hath he covered. . . . Therefore, behold, I will proceed to do a marvellous work among this people, even a marvellous work and a wonder: for the wisdom of their wise men shall perish, and the understanding of their prudent men shall be hid. . . . They also that erred in spirit shall come to understanding, and they that murmured shall learn doctrine. (Isaiah 29:9–10, 14, 24)

In coming to know us, you’ll learn quickly that we believe not only in God the Eternal Father, His Son Jesus Christ, and the Holy Ghost but also in angels—resurrected beings, divine messages, and messengers of all scriptural kinds. In a word, we believe in modern revelation as it was given in past dispensations and which we believe should always characterize the true Church of God.

That is an essential prelude to my message because we believe the dawn of that marvelous work and wonder, to which Isaiah referred, came in the spring of 1820 when a young man not yet fifteen years of age desired to know if the true, original New Testament Church of Jesus Christ was still on the earth. Acting on pure faith and in response to a single biblical verse, James 1:5, “If any of you lack wisdom, let him ask of God, that giveth to all men liberally, and upbraideth not; and it shall be given him,” that boy, with the plainest of Anglo-Saxon names, Joseph Smith Jr., prayed vocally for the first time in his life. In response to that prayer, what happened next is, to believers like myself, the most important revelatory event for mortals to have witnessed or to have heard about since that little band of disciples gathered on the Mount of Olives to witness Christ’s final hours on earth. On that day of ascension, two angels had said to the group, “Ye men of Galilee, why stand ye gazing up into heaven? this same Jesus, which is taken up from you into heaven, shall so come in like manner as you have seen him go into heaven” (Acts 1:11). Just days later, the Apostle Peter added, “[He] whom the heaven must receive until the times of restitution of all things, which God hath spoken by the mouth of all his holy prophets since the world began” (Acts 3:21). We believe that spring day in 1820 was the beginning of that second messianic return in a vision, which the young Joseph Smith described as being “above the brightness of the sun” (Joseph Smith—History 1:16). God the Eternal Father and His resurrected Son, Jesus Christ, appeared to him in breathtaking glory.

This is our message to the world—and surely you have seen some of our approximately seventy thousand young missionaries that are laboring around the world sharing that message—that the day of restitution prophesied so long ago has begun, including a step-by-step restoration of all that was in the primitive Church, including twelve Apostles and the other Church offices of that day—all in anticipation of Christ’s triumphant, much more public and final, return to rule and reign as King of kings. The appearance to young Joseph Smith was only the precursor. So the day of that vision in 1820 is inextricably linked with my day at Oxford with you.

Both days presuppose certain truths. One of those is that in New Testament times there was a true Church, of which Jesus Christ was the chief cornerstone and the personification of divinity, with mortal men called as prophets and apostles to form a foundational structure around Him. These Apostles with other teachers and priests, pastors and members, constituted a figurative building—a Church, if you will—fitly framed together, which Paul described as “for the perfecting of the saints, for the work of the ministry, for the edifying of the body of Christ” (Ephesians 4:12).

Another truth fundamental to my visit with you today is that the New Testament Church was expected to exist, or at least it is assumed it was expected to continue to exist, until that glorious, final appearance of which these angels spoke of in the book of Acts. There were Jesus’s teachings to be taught, His saving ordinances and sacraments to be embraced, and a community of believers to be established that would serve and strengthen individuals, families, neighborhoods, and nations by putting on what Paul called “the whole armour of God” (Ephesians 6:11).

Sadly, however, the Church did not withstand what Paul went on to call “the wiles of the devil” and “the rulers of the darkness of this world” (Ephesians 6:11–12). After Christ’s ascension and the gradual, inexorable death of the early Apostles, the divinity of the Church and its orderly succession of ordained, authorized priesthood administers was gradually lost, removed from the human family. Without apostolic keys and authorized priestly oversight, over time the doctrine either eroded or in some cases was corrupted, and unauthorized changes to the saving ordinances were introduced. What then ensued was more than a millennium of institutional darkness, leading to the divisions and divergence and religious disarray of many kinds and dashing Paul’s hopes that there would be a unity of the faith and a knowledge of the Son of God. It belabors the obvious to note that in the Christian world we do not enjoy anything remotely approximating a unity of faith today, nor a common church fitly framed together. Indeed, those in the contemporary religious culture—if we can call it that—particularly the young, seem well and truly “tossed to and fro, and carried about with every wind of doctrine” (Ephesians 4:14). But Paul still gives voice to all who would yearn for that “one Lord, one faith, one baptism” (Ephesians 4:5) of the original New Testament Church.

And so it was in Joseph Smith’s day; the young boy prophet lamented that his region was a scene of great confusion and bad feeling: priest contending against priest, convert against convert so that any good feelings were entirely lost in a “war of words and a tumult of opinions” (Joseph Smith—History 1:10). That confusion led to the prayer I have mentioned and the theophany that followed. So, what brings me to you today is not a message of reformation but of restoration. The Church that Christ established by His hand in the meridian of time has been restored by His own hand in this present time. This is a fundamental way in which The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is for the most part distinct from most, virtually all, of contemporary Christian churches—a distinction without which one cannot fully understand our history, our doctrine, or our fervor in sending out missionaries to all the world. Our basic message, then, about Christ’s restored Church and doctrine is not limited to but might begin with these truths:

First, every man, woman, and child who has ever lived, now lives, or will yet live, so long as the earth shall last, is a son or daughter of a loving and divine Heavenly Father. He is the God in whose image we were created as the spiritual offspring to God. We are “heirs of God and joint-heirs with Christ” (Romans 8:17). To gain a mortal body and experience moral growth available in no other way, a real Adam and a real Eve chose to leave the paradisiacal setting—Eden, if you will—to learn all that was necessary for the children of God to learn. They especially learned about living together in love and realized that the guidance of God would give them the only real answers to personal and familial, social and political, economic and philosophical problems that they would face in mortality. Because mistakes would be made in the course of the mortal education, sometimes horrible mistakes, a Savior was provided for such a plan, one that would not only atone for Adam and Eve’s initial transgression but also for every individual transgression that was made for all those in the human family: the sins and sorrows, the disappointments and despair, the tears and tragedy of every man, woman, and child who would ever live. Such a plan was necessary, and such a Savior was required because life is eternal. Our hopes and dreams mattered before we came to this earth, and they will most certainly matter after we leave it. We say with Job, “Though after my skin worms destroy this body, yet in my flesh shall I see God” (Job 19:26), and say with the Apostle Paul, “If in this life only we have hope in Christ, we are of all men most miserable” (1 Corinthians 15:19). Lastly, this plan, this divine course outlined for us, including the fortunate Fall in Eden and the redemption of Gethsemane and Calvary, is universally inclusive. All are children of the same God, and all are included in His love and His grace. “For as in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 15:22). Everyone is covered, though it remains to be seen whether everyone cares, but if there is a failure to respond it won’t be because God didn’t try and Christ didn’t come. That is at the heart of what I have been introducing to you as the restored gospel.

Now in light of what I considered is reasonably straightforward biblical theology, one may wonder: Why did these Latter-day Saints stir up such emotions in people, and why are they not considered Christian by some? Let me conclude with just a few thoughts on that. We are not considered Christian by some because we are not fourth-century Christians; we are not Nicaean Christians; we are not creedal Christians of the brand that arose hundreds of years after Christ. No, when we speak of restored Christianity, we speak of the Church as it was in its New Testament time, not as it became when great councils were called to debate and anguish over what it was that they really believed. So if one means Greek-influenced, council-convening, philosophy-flavored Christianity opposed to Christianity in apostolic times, we are not generally considered that kind of Christian. Thus, we teach that God the Father and His Son Jesus Christ are separate and distinct beings with glorified bodies of flesh and bone. As such we stand with the historical position that the formal doctrine of the Trinity as it was defined by the great Church councils of the fourth and fifth centuries is not to be found in the New Testament. We take Christ literally at His word that He came down from heaven not to do His will but the will of Him who sent Him. Of His antagonists, He said they have “hated both me and my Father” (John 15:24). These along with scores of other references, including His pleading prayers, make clear Jesus’s physical separation from His Father. However, having affirmed the point of Their separate and distinct physical nature, we declare unequivocally that they are indeed one in every other conceivable way—in mind, in deed, in will, in wish, in hope, in faith, in purpose, in intent, and in love, but they are separate and distinct individuals as fathers and sons are. In this matter, we differ from traditional creedal Christianity but do agree with the New Testament perception.

We also differ from fourth- and fifth-century Christianity by declaring that the scriptural canon is not closed, that the heavens are open with revelatory experience, and that God meant what He said when He promised Moses, “My works are without end, and also my words, for they never cease” (Moses 1:4). The Book of Mormon, which is subtitled “Another Testament of Jesus Christ,” and other canonized scripture as well as the role of living oracles bear witness to the fact that God continues to speak and to guide His children here on earth. Coupled with the Holy Bible, there is no document more powerful than the Book of Mormon as evidence of God’s continuing, loving voice and as witness of the divinity of the Lord Jesus Christ. The Book of Mormon is that other half of Isaiah’s prophesy with which we began of which the prophet went on to say, “And the vision of all is become unto you as the words of a book. . . . And in that day shall the deaf hear the words of the book, and the eyes of the blind shall see out of obscurity, and out of darkness. The meek shall also increase their joy in the Lord, and the poor among men shall rejoice in the Holy One of Israel” (Isaiah 29:11, 18–19). I, for one, would feel to walk on hot lava and chew broken glass if I could find a document, any document anywhere, containing any new words of Christ—fifty words, twenty words, one new word from the Son of God—let alone hundreds of pages that record the appearance, teachings, covenants, and counsel He gave to a heretofore unknown audience. Because I want you neither to walk on hot lava nor chew broken glass, I have gifted copies of the Book of Mormon for those of you that would like one at the end of this lecture.

In any case we agree enthusiastically with the insightful Protestant scholar who inquired, “On what biblical or historical grounds has the inspiration of God been limited to the written documents that the church now calls its Bible?... If the Spirit inspired only the written documents of the first century, does that mean that the same Spirit does not speak today about matters that are of significant concern?”[1]

Lastly, for today, we’re unique in the modern Christian world regarding another matter, which a prophet and a president of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints called our most distinguishing characteristic, that is divine priesthood authority to provide the living sacraments, the saving sacraments, the ordinances of the gospel of Jesus Christ. The holy priesthood, which has been restored to the earth by those who held it anciently, signals the return of divine authorization. It is different from all other man-made powers and authorities on the face of the earth. Without it there could be a church in name only, and it would be a church lacking in authority to administer the things of God. This restoration of priesthood authority eases centuries of anguish among those who knew certain ordinances and sacraments were essential, but lived with the doubt as to who had the right to administer them.

Breaking ecclesiastically with his more famous brother John over the latter’s decision to ordain without any divine authority to do so, Charles Wesley wrote,

How easily are bishops made

By man or woman’s whim:

Wesley his hands on Coke hath laid,

But who laid hands on him?[2]

In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, we can answer the question of who laid hands on him all the way back to Christ Himself. The return of such authority is truly the most distinguishing feature of our faith. Not long ago I happened across a quotation from one who had a ministry, not in England but in New England, a century ago. This plain-spoken cleric wrote:

The loss of respect for religion is the dry rot of social institutions. The idea of God as the Creator and Father of all mankind is to the moral world, what gravitation is in the natural; it holds everything else together and causes it to revolve around a common center. Take away that and any ultimate significance to life falls apart. There is then no such thing as collective humanity, but only separate molecules of men and women drifting in the universe with no more cohesion and no more meaning than so many grains of sand have meaning for the sea.[3]

I hope I’ve said something that can counter the loss of respect for religion and expunge what in some settings is the dry rot of modern, social institutions. My convictions about The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and the gospel of Jesus Christ mean everything to me. Certainly it is the common center of my existence around which everything else revolves. It produces, protects, promises, or points to every good thing I possess now or hope to possess in the future. Thank you for your attendance; I am honored by your invitation and complimented by courtesy and hospitality. I say that expressly of my beloved friend Andrew Teal. May the love of God be with us all and may the Church, the truth of Christ, and the truth in Christ save our souls and make us free. In the name of Jesus Christ, amen. Andrew, thank you.

Teal: Thank you, Elder Holland. It is great to be here in this historic place that Elder Holland was commenting on. On this Thanksgiving Day, it is great to be here together. There was another theological conversation in the sixteenth century between Thomas Cranmer and some persecutors, and so I hope that the outcome of today’s gathering will be a lot better for all of us. But Broad Street is just right there for whatever. [laughter]

Holland: Is that smoke I can smell? [laughter]

Teal: This is also a place where the Oxford Movement began, which transformed and challenged the nature of the Church of England to ask deep questions about, among other things, apostolic succession. And it’s where a former vicar of this church, John Henry Newman,[4] came to terms with the fact that apostolic succession was one of the things that could not be argued back into the nature of the Church of England. Apostolic succession seemed to be a real hot potato. This is also the very room where Oxfom was founded in 1942, so it’s a great thing on this Thanksgiving Day. There are a lot of things to be grateful for and most particularly Elder Holland. It’s a long path from Salt Lake City, but the path of Christianity is even longer. It’s a moving path, where only God is both consistent and true, and He has integrity as He moves with us through the steps of time. With His support we find new words and renewed life to bear witness to journey with real tensions. We want to be consistent with what is true and what has been revealed, and we also want to say that actually, for us, the golden age is not in the past; archaeology is not the answer; it’s eschatology; it’s the end-time. On this path there have been many stages of development and change. My specific research area is the fourth and fifth centuries, and one of the things that you find there is that people like Athanasius will use words, different words, in order to try to move things on, and now even those ways of seeing things can be recognized as important even if we later look to other emphases in doctrine.[5] Steps the Christian community had to take as a sort of progression, in time, may have to be reviewed again. An Anglican theologian, Richard Hooker, said (and I paraphrase!), “That which was once best might now be worst.”[6] He wanted to say that in early Anglicism there needs to be a real determination to bear witness of the significance of this journey and Christ, the one who accompanies us—He is the one who teaches, mentors, eats with, and travels with us, coming bearing eternal truths. Our theological conjectures tell us more about ourselves than Him all too often, but His patience is astounding!

Today we can listen together and commit to a real determination to discuss, a commitment to really understand, to explore, to enjoy, and to converse with true love and affection. This commitment is almost radiantly palpable, and that doesn’t mean we need to collapse into politeness—far from it. Respect and love allow a real openness to truth. Therefore, I think all of us here, I hope, are determined to be aware that our history should not collapse our discussion today into distant categories so that we can label one another.

For example, one of the things that I have been discussing with Paul Kerry is the nature of language describing the personhood of God. God isn’t like Wi-Fi, which is here interfering with our mobile phones and making strange noises, but God always comes in a personal way. He always comes incarnate and rather than say, “Well, when you talk about the personhood of God and the embodiment of God, that’s the anthropomorphite controversy of whatever century.” We are obliged to ask ourselves: What is the language of the tripersonal God and His unity? Can we commit to working together and finding a vision of the God who weeps at human brokenness, lack of hospitality, and harshness of mind and heart, yet who doesn’t abandon us but time after time draws near?

So that’s what I really hope is the beginning of a significant journey to say we need to understand each other and work together and love one another.

I suppose the first question is a really steep path. There is no rehearsal for this. A friend of mine gave me a small sign to put on the door that said “You’re never ready for what you have to do: you just do it. That makes you ready.” And we, as humans, don’t like that. We like to have everything carefully prepared and secure, especially if we are involved in organizing things like this. So the question is: On this journey, how does The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints try to form people into a consistently flexible community? What’s been difficult in helping people to take some things as eternally true and to see that it is likely that other things will change? I know all of our churches have changed massively, but that doesn’t exclude some very significant challenges that we must face together. What is that formation like?

Holland: I think, Andrew, probably a fundamental principle for us in this regard would be the principle of ongoing revelation. It reinforces the fact that we need to be tentative to some degree when looking back and looking forward. We realize that God has not revealed everything that He is going to reveal. One of our articles of faith is that we believe that God has revealed, does now reveal, and will yet reveal great saving truths, and that has an impact on us individually and as an institution. It has an impact on individual faith and belief, so I think it’s obligatory for us to remain open (perhaps tentative is not as good a word as open) to reflection, review, history, insight, and revelatory experience. Whether that is in scientific, economic, political, or more straightforward theological terms, we need to be open to that. We can’t be fixed; we, by definition, can’t be locked into a position that is not open to continuing revelation. Whether we honor that well can be a matter of opinion. Some of us are more rigid than others, but I think that would not be the fault of the Church. The Church is solidly predicated on the idea of revelation.

Teal: The central question that I think Jesus asks is always “Whom say ye that I am?” (Matthew 16:13), and that’s quite a hard question to answer, but today we have heard about His relation to God the Father, and His distinctness from God the Father. So already we are in the realms of mystery and revealed mercy. Frederick William Faber, one of Newman’s friends, said, “There’s a wideness in God’s mercy, like the mercy of the sea. There’s a kindness in God’s justice, which is more than liberty.”[7] And I think that connects with what you said about how, in fact, part of the gospel committed to us is revealing a God that is more generous in His views and boundless in His mercy and blessings than we can conceive. So does the genre of doctrine have to be honed to what you described as the eternal gospel, that there is no one who ever has been or ever will be, who can’t be a part of that wonderful blessing? Is that the defining boundary?

Holland: If I understand the question, you are probing a basic, defining principle for us. Salvation, as extended through the plan of God and the incarnation, the ministry, and the Atonement of His Son, is all-inclusive. Every man, woman, and child ever to exist is covered by the atoning grace and mercy of Jesus Christ. Because of this gift, there are some things that are expected in terms of a godly walk; there are some implications of this belief that would dictate how people should behave. We do believe firmly in the sacraments; we do believe in ordinances, but we believe those come as a consequence of one’s faith and as a response to the feelings that he or she has had in coming to understand the universal gift of Christ’s Atonement. Down through the centuries, in the era of the Old Testament, people would have known a great deal about God’s justice, they would have known a great deal about His omnipotence, they would have known a great deal, on occasion, about His anger, but I think what He had not been able to convey successfully to us as mortals was His love and His mercy. So the ultimate gift and manifestation of who God is was the embodiment and the incarnation of His Son. It was through the life of Christ, God’s greatest gift and His greatest blessing, that the Father primarily showed the grace, mercy, and love that we know of, teach of, testify of, and identify with. That brings us back full circle to the idea of God and Christ’s unity, for Their mercy, truth, grace, and love is the same. The only distinction between Them that we make is that They were and are two physically distinct beings, that when Christ prayed, He was praying to Someone. When He said, “Father, forgive them” (Luke 23:34), He was talking to His Father and asking for forgiveness to be extended to His tormentors. But other than that physical distinction, the unity, especially of Their love, mercy, and grace, is inseparable, inextricable—a witness that we’re anxious to bear and have understood as our institutional position.

Teal: One of the things I think that other churches, other denominations, find puzzling is the baptism for the dead, which the Apostle Paul writes about, but you’ve viewed this as an extension of the mission of mercy.

Holland: That’s exactly right.

Teal: In the Orthodox tradition of the twentieth century, a great, saintly man named Silouan the Athonite experienced the devastation of the Bolshevik Revolution on the Orthodox Christian community. For him, too, it was heartbreaking to see the destruction and desecration of cathedrals and churches and the fabric of faithfulness. Another Russian visited him on Mount Athos. He said, “‘God will punish all atheists. They will burn in everlasting fire.’ Obviously upset, the Staretz said, ‘Tell me, supposing you went to paradise, and there looked down and saw somebody burning in hell-fire—would you feel happy?’ ‘It can’t be helped. It would be their own fault,’ said the hermit. . . . [Silouan] answered him with a sorrowful countenance: ‘Love could not bear that,’ he said, ‘we must pray for all.’”[8] In this city, and very probably in this very location, the Anglican Church rediscovered the nature of the infinite Atonement and a Christian responsibility to pray for others, the living and the dead, in the name and authority of Him who lived and died and who grasped all in every kind of self-alienation and despair, the living and the dead. We trust that those prayers will gently lead all to Jesus Christ with devotion, care, humility, self-sacrifice, and compassion. So the extension of an actual sacrament to the dead in some churches is the Absolution of the Dead. In a way, is this a manner of understanding baptism for the dead?

Holland: Indeed, it is. For us it would be a cosmic, monumental injustice to say that someone who had never even heard the name Jesus Christ and was born in an era where that language wasn’t used and in a culture where it was not understood would be condemned to hell, that somehow these people could be cast off through no act or choice of their own. To pass judgment because of the inadvertence of their birth and ancestry would seem to be the most blatant injustice of eternity. So, as you noted, Andrew, we do perform a vicarious ordinance, as Paul taught, but its acceptance is optional. I don’t know whether there are attorneys in the room, but the vicarious ordinances performed are an “offer” to the dead, and of course offers have to be accepted to be contractually binding. We are not assuming that everybody is going to accept that ordinance or that they will choose Christ any more there than they chose Him here in mortality. But we do believe that it would be a terrible injustice and no act of mercy in any way to preclude people simply because they were born in a time, place, era, culture, or dispensation where the gospel of Jesus Christ was not available or His name was not even known. To provide for them is a part of that universal embrace that we speak of.

Teal: There are many people who live inspiring lives and can bring about a reorientation towards God in every generation. Can you envisage a day when, through conversation, common understanding, and prayer, Joseph Smith will be recognized as a prophet for the broader Christian Church? Can you envisage a day when people will say, “Lay aside some of the aggression and recognize that he was a human being in his era—a simple, ordinary man to whom the living God spoke, and through whom He worked,” and would that be something that you would hope for?

Holland: Oh, I would definitely hope for that! Whether I can envision it or not, I’m not sure, but I can hope for it. I would hope for it on the basis of merit. To use Joseph Smith as the example, I would hope for it on the basis of what he taught, seeing that as consistent with what seems true, what sounds true, what feels true, and is consistent with what you, or I, believe is true. So I wouldn’t expect such loyalty in the absence of faith. I wouldn’t ask that someone suspend reason and good judgment and accept my witness just because I say it, but I would invite the kind of investigation that asks: What did Joseph Smith teach? What did he stand for? I would ask the same of someone investigating Peter, Paul, or anyone else of such standing, and let the truth fall where it may, let that spiritual conviction come if it comes. That is one of the reasons why I believe that one of the first gifts, one of the first of the Church’s institutional messages to the world came in the form of the book. It was tangible; it was readable; it was shareable; it was portable. And it didn’t rely on an act of faith, though faith is ultimately at the basis of everything one believes. The Book of Mormon doesn’t require blind faith. It was intended to start an open conversation, then let the merit of the conversation carry the reader where it will. That kind of universality for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints I can envision, and it’s what I would truly hope for. Then I would let the truth and spiritual witnesses come where they come, taking our chances with that.

Teal: One question that is interesting is that some other early Christians speculate that there were two creations, a spiritual one and then the Fall, and the Fall is why we are in flesh. Now that seems to be rather different from what you were saying about how, in fact, there is a premortal existence of men and women, and the Fall is not so much a fall but a step, a pedagogical, educational step. So does that mean that the Fall of Adam and Eve was a choice?

Holland: We are fairly emphatic about the reality of Adam and Eve and impact of the Fall. We do talk about the Fall and about a fallen world as part of a plan linked to the Atonement of Jesus Christ. We do not see it as an ignorant step. We believe that the exit from the Garden of Eden was given as an option and that Adam and Eve could have theoretically stayed in the garden forever. But it is also our doctrine that if they had chosen to stay in the garden, then none of the rest of us could have joined them on earth. So, they chose to leave in order that we might be. They chose with the understanding that there would be a Savior who would come and be, as Paul said in Corinthians, another “Adam” (1 Corinthians 15:45, 47). And so Adam and Eve were involved in the Fall, and the other Adam, Christ, was involved in the redemption. And so you get that little couplet, “As in Adam all die, even so in Christ shall all be made alive” (1 Corinthians 14:22). They become the bookends of a plan that brings us into mortality, gives us learning and a physical body, then provides a way for us to leave with a resurrected body, which we all celebrate, and which, I think, is sometimes too understated in Christianity. When we talk about an unembodied God, it’s hard for me to reconcile that with all the emphasis that Christians supposedly place on the Resurrection. What was so significant about the Resurrection if we don’t see a need for divinity to be embodied? Yes, we are very emphatic about the Fall, but it was a fortunate fall; it was a step, knowingly made, into mortality with some promises conveyed that would reassure Adam and Eve that there was a way up out of that Fall, into eternal life.

Teal: There is an ancient hymn of the earliest Church called the Exsultet sung during the night of Easter, and one of the couplets from that is “O happy fault, O necessary sin of Adam.”[9]

Holland: That could be our hymn; we could adopt that.

Teal: I will send you a copy! But it seems to be a celebration of our bodies; it gives the sense of a happy fall that is the foundation of the Resurrection. And this thing about bodies, enjoying looking after and engaging with our bodies, seems to be in the culture of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. For example, there appears to be a real enjoyment of things like dancing. In fact, if I could quote a Latter-day Saint singer of a group called The Killers, Brandon Flowers, there is a song with lyrics “Are we human or are we dancers?,” and I actually think the answer is that we are both.

Holland: Both. We haven’t gone around as advance men for The Killers, but we acknowledge that truth in their song.

Teal: But the Exsultet is better then?

Holland: Right, and so is the Tabernacle Choir!

Question 1: I have the first question. When you spoke, you mentioned a time of overt persecution of the Church and that we must strive for something like normalization or the idea of overcoming the distance we put between ourselves. Could you explain and expound on that? What are your thoughts?

Teal: I remember Elder Holland saying how the Latter-day Saint community brings with them the experience of being the only community, as far as I am aware, in the United States that had an order for extermination.

Holland: That’s right, an extermination order.

Teal: That was in Independence, Missouri. But in a sense, that prompted, despite it being a dreadful thing, a journey and, if you like, the carving of a frontier spirituality.

Holland: It played a significant part in forming the character of the Church in its first century of existence.

Teal: With progression there also comes opposition, aggressive reactions, and attempts to undermine.

Holland: I think that tension will always exist. For us, it had a very binding, covenantal impact. It drew those pioneers, those refugees, together. They depended on each other very, very much; thus was born an early heritage of service, care, and watching out for each other. But, Andrew, I also think the idea is important that although we were even driven, quite literally, across the United States and finally beyond the then existing territorial lines of the United States, we never felt like we were retreating from or taking ourselves outside of that community. Almost immediately after arriving in the Great Basin, there was a spirit of growth, education, and engagement in the political processes that would allow us to return to the community. We’ve never seen ourselves as being a community that wanted to be “loners,” to be outside the circle of a Christian, cultural, or political community. I think the history of the Church now shows that return. A year or two ago, we had not one but two candidates running for president of the United States who were members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. For me, I wouldn’t have cared very much for the negative political consequences that surely would have come to the Church had either won, but the symbol of these candidates running shows that we meant to return, planned to return, and have returned to be part of the larger community and be in a normalized, comfortable relationship with our neighbor. We have worked very hard at that and have tried to make sure that we are inclusive and not exclusive.

Question 2: We live in a time when many social justice advocates are saying that religion is out of touch, that it fails to meet the needs of large groups of constituents including women, the LGBTQ+ community, minorities, and individuals. However, a theology student of deity and Christian theology, and specifically of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, will find answers to many of these claims. Attention is being brought to lost scriptures that exonerate women and an existence of a divine Heavenly Mother alongside the Father. However, these doctrines remain largely trapped in theological discussions, out of reach of the average religious discourse. Therefore, how can we bring these great theological truths, which for too long have been regarded as deeper theology, to the surface level in order to answer these claims that the Church is no longer in touch with common humanity?

Holland: That’s a great question; that’s a great speech. Did we get that all down? I actually think what Andrew Teal is doing this very minute with us and what he does with others, such as with my two sons and Paul Kerry, is to encourage that kind of conversation. I’ve heard him use the word conversation a dozen times since we met on the street and walked up here, and that is a compliment to Andrew. It shows that he really wants that climate, that attitude, that openness: the openness of both personal and institutional faith. We are not always this welcomed; we are not always so warmly invited, in many places. So there are symbolic steps in understanding, like this very experience today and the freedom you have to ask that very question. We need to find ways to do more of this. When we have these conversations, what we’ll find is that we have far more in common than we have differences. In unity we will have more impact, more energy, and far more inspiration. We’ve let some differences, and I acknowledge that there are significant doctrinal distinctions, get in the way of warmer, wonderful conversations wherein we realize we have much in common and that much good can be done together. Earlier, I referred to the declining respect for religion being termed the “dry rot of social institutions.” We must never allow religion to be relegated to the position of some sort of ancient appendix that is essentially useless, can be dangerous, and needs to be excised for safety’s sake. Religion is still the answer to the world’s problems. A little nun, when they discovered her effects, had just a sari or two, a sweater, and a little three-by-five card by her scriptures that said “With God all the rules are fair, and there are wonderful surprises.” We need to engage in the surprising part; we need to start to talk about those, because surprises are available right now. We just need to talk about them more.

Teal: One of the things that I think is wonderfully clear is that there is a lack of defensiveness in this conversation. And if you read some of the things that are produced by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, there is a recognition of much common ground. I remember hearing somebody say, “It may be a million miles away from where I am, but whatever you are, wherever you’ve been, come and talk, and we will try to be clean together. We will try to respect one another and build each other up.” And there’s that sense of recognition, respect, and dignity. This means openness. We represent institutions, which are important, and we have to recognize that there are times when we have been a million miles away from embrace, understanding, and the twinkling of an eye when we disagree with something. We can still smile and be friends and keep on working on misunderstandings and disagreement. And that works in terms of doctrine, but it also works in terms of how all the mainstream religions, not just Christianity, have treated women, how they’ve treated people of different classes, how they’ve prioritized some people. All of that needs to be owned and addressed.

Holland: And the first obligation forever and ever is that we love God and love each other. If we could remember that, begin with that, and do that, I can’t really imagine a serious conversation getting into trouble. Sometimes we leap to other issues and other differences, including doctrinal differences, and forget, unfortunately, that we’re committed to love. If we can just anchor ourselves there, then I think we’ll find an answer to other questions that we have.

Question 3: I love this conversation that’s taking place here on the faith traditions in the way they are traditionally understood. And I just want some insight on this about the apostolic succession for bishops and the schism between the Western and Eastern branches of the Church.

Teal: Well, I think of the Church in the West in terms of Roman Catholic and Protestant traditions and the Church in the East in terms of the Orthodox. I do recognize apostolic succession, but there are many complex and nuanced schisms over this issue. Now, two weeks ago, the patriarchate of Moscow and the patriarchate of Constantinople divided. This doesn’t mean they don’t think there are proper ministers with apostolic succession, but there is a whole question about what apostolic succession means. Does it mean that there has to be a tangible, physical passing on of that apostolic authority by the laying on of hands? Is it sort of like a drain pipe where you’ve got to have everything connected? Or is it more like something from the Protestant wing of the reformed Church of England, which wasn’t really concerned about apostolic succession because it was much more about the Bible, and there was yet another argument that there was a residual apostolic succession. One of the things that happened after the Oxford Movement was a papal investigation that took place to see whether or not Anglican priests could claim to have apostolic succession (like the Old Catholics), and in wonderful clarity, perhaps less charity, they said Anglican orders were “absolutely null and utterly void,” in other words, completely powerless.[10] So that, in a sense, is where the Anglican Church stands in the definition of the Catholic Church: the Anglican ministers are ministers, but they’re not priests. And one of the things that you talked about was apostolic succession and restoring the priesthood. Temple rather than church—is that the reason why you build temples in Chorley, and indeed all over the world?

Holland: Thank you for raising that, Andrew, because people often have that very question. We have our regular worship, our regular daily, weekly worship, in chapels and meetinghouses as almost any church would do. The temple is distinct with us in the sense that it is reserved for the highest ordinances, the most sacred sacraments, and not for the weekly worship where we gather as families, sing our hymns, and have our prayers. For example, the work that we talked about for the deceased, where we do work for our own kindred dead, our own ancestors, is reserved for a temple. The temple is not a secret. In fact, any time we build or renovate a temple, we have an open house so people can come in and see its beauty. Once it’s dedicated, however, it takes on a special sanctity, and it is reserved for special, holy ordinances. We have 150-something temples (and counting), but we have probably twenty thousand chapels or meetinghouses or other places of worship around the world for daily and weekly use. That is the distinction that we make for the two temples in the UK—London and Preston—you have mentioned.

Teal: And the priesthood for all the believers, in a sense, is apostolic succession, the Aaronic Priesthood. Is that how priesthood is construed?

Holland: Yes, we do make the priesthood available to all worthy males, but there is a worthiness aspect. One does not simply step forward and say, “I claim the priesthood” or “I have ordained myself.” There is a process. We speak of keys; we talk about the transmission of keys by the laying on of hands, but the priesthood is universally available for the men who meet the worthiness standards. I hasten to stress that women and children all participate in the blessings of that priesthood as well. There is a male ordination involved, but the priesthood influences and affects all—men, women, and children. For example, babies can receive a priesthood blessing at birth. You and I were talking about this before this event and how it is the equivalent of your christening. So the priesthood is experienced by individuals and entire families from birth forward.

Question 4: I’m a philosopher, so I could talk about this all day. I love that excuse. Elder Holland started talking about the reasons members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints are regarded as Christians; Christianity started with the doctrine of the Trinity, and then he went on to describe the oneness of the Godhead in a way. You could understand what he described in terms of being of one essence, of one nature but of three distinct personages. I heard you, Reverend Teal, express a willingness to rethink the way we describe the experience of God, the experience of divinity. So I guess my question is just how important do you think this physical oneness is? It seems to get in the way so often of our chances to talk to each other, our treating each other with respect.

Holland: The wonder of today is all a tribute to Andrew Teal. You heard him introduce me and ask these questions. He knows more about what we believe and what we don’t believe than some of our own members, and that is the proper way to have a gospel conversation. You knew that it was in Missouri that an extermination order was issued; you knew about the distinctiveness of the Book of Mormon; you are familiar with Joseph Smith’s history. You knew that before I walked in this room. That is the way to cut through metaphysical difficulties. There might be some metaphysical challenges that arise along the way, but if they arise with common understanding and common vocabulary, then I think we can handle them courteously and comfortably. In short, we need to keep those first two great commandments, and that is the ultimate compliment to you today, Andrew. You have invited us with courtesy and knowing more about us than some of us know about ourselves. That truly is the ultimate compliment.

Teal: We need each other’s eyes to see ourselves. I think this is why something living is going on.

Holland: And that’s why we will find that good people have more in common than in difference. In regards to my own education regarding the Trinity, as a young man (like one of these young men back here with these missionary name tags on), I was quite sure that I knew everything that the apostolic Church believed, traditional Christianity believed, the Roman Catholic Church believed, and everybody else believed about the Trinity. Well, embarrassingly, I’ve learned that I didn’t know very much about what they believed. But, if we can start talking about what we have in common, where we do agree, like we have in these kinds of conversations, then it is a lot easier to fine-tune the issues—we get more light and less heat. The differences may be significant, but if they are discussed in a spirit of goodwill, we can come to understanding. I get interviewed in many of the places I go. The only thing I have ever asked from a journalist or the one who is interviewing me is to please not tell me what I believe. So often someone will say, “Well, now you Mormons believe,” and I have to stop them there and say, “Well, I am going to be interested in what you say because then I will tell you whether I believe that or not.” It is just a lot nicer to do it the Andrew Teal way, who will say, “If I understand correctly, this is the Latter-day Saint position,” or “Please tell us what you believe regarding . . . ,” then the conversation starts at such an elevated level, at such a courteous and informed level. It often turns out we agree on more than we realize, and it gives us ground to discuss where we don’t agree. I loved your word envisage; I loved your word hope. Could it possibly be that if we learn together in the spirit we have felt today, that we could be closer to true brotherhood and sisterhood than we thought possible? Closer together and not further apart? I really, truly believe that with all my heart.

Teal: Yes, me too. We’ve had a really marvelous time, and we have a wonderful note here to almost end on, but we wanted to leave it in case someone had a final question here.

Question 5: I guess I mostly just have a question about priesthood. And I was wondering what your understanding of priesthood is and why it requires a formal ordination. And obviously during different periods, the definition of priesthood has been known to many different groups of people, but that question is more of if the priesthood, or however God wants to interact with humanity, transcends this notion. Reverend Teal mentioned that it does, and Elder Holland mentioned how priesthood sort of affects all people: men, women, and children. So my question is basically what is the significance of ordination, and why do you need to control it in that formal sense?

Holland: Maybe that question is directed to me because we are the ones that say it requires ordination. I’m not sure what actually happens when hands are laid upon a person’s head but something is being communicated in that touch, that contact. And I do know that keys and authority must be held in order for one to give keys and authority to another. As for control and regulation, I’ve wondered if part of the answer is that ordination can be a protection against abuse and profligacy. Let me use a horrid, extreme example. Some evil, truly evil person might like to say, “Well, I claim the priesthood; I have it, and I’m God’s spokesman, now I’ll proceed to destroy that family, or ruin this nation, or hurt this individual, and will do it all in the name of the priesthood.” That could still happen, I suppose, if an evil person somehow had hands laid on his head, but I think it is less likely if other worthy people are involved in the process. I think there is some governance, some actual protection against a “come one, come all” attitude of self-appointed priesthood. That’s why I went to some length to make clear that worthiness distinction about the universal availability of the priesthood. We do believe in universal access, but we do not believe that one can just assume it, and I just wondered aloud with you, if that isn’t some protection against one trying to claim a godly power in order to try to do some harm. At least there is a check and balance if one is found worthy by another who holds the keys to pronounce worthiness. God’s house is a house of order, and the priesthood makes unique use of the word “order.” It has the same root meaning as “ordain.”

Teal: Thank you all for being here as we take these steps.

Holland: Thank you; I love you. I’ve just extended a formal invitation to Andrew to come to Brigham Young University next spring. We’ll transport all of you over there for a continuation of this conversation. We promise to be just as courteous there as you were here. Please, I insist. What a generous and good man! Thank you, Andrew, thank you. I love you.

Notes

[1] Lee M. McDonald, The Formation of the Christian Biblical Canon, rev. ed. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 1995), 255–56.

[2] Quoted in C. Beaufort Moss, The Divisions of Christendom: A Retrospect (n.d.), 22.

[3] Adaptation of original quote by Henry Martyn Field (1822–1907), longtime editor of The Evangelist. More easily accessed at greatthoughtstreasury.com.

[4] Who is to be canonized as a saint in the Catholic and Anglican churches on Sunday, 13 November 2019, by Pope Francis in St. Peter’s, Vatican City.

[5] Athanasius, for example, clearly has a vision of the necessity of apophatic theology to prevent our idolatry of language and intellectual constructs, as necessary as they are in the light of error. See his Contra Arianos.

[6] Richard Hooker, Laws: III.x.5, https://

[7] Frederick William Faber, “There’s a Wideness in God’s Mercy,” Hymnary.org, https://

[8] Archimandrite Sophrony (Sakharov), Saint Silouan the Athonite (Essex, United Kingdom: Stavropegic Monastery of St. John the Baptist, 1991), 48; emphasis added.

[9] “O Felix Culpa” (O Happy Fault), Exsultet.

[10] Pope Leo XIII, Apostolicae Curae, w2.vatican.va/