Introduction

Andrew Teal

Andrew Teal, "Introduction," in Inspiring Service, ed. Andrew Teal (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), xi–ix.

The Genesis of an Idea

I begin with a disclaimer. It is all the more interesting, moving, and challenging to dive straight into this volume’s records of an extraordinary weekend in Oxford towards the end of Michaelmas term in 2018 than to begin bogged down in this introductory description, commentary, and agenda. I am persuaded to submit an introduction only on the understanding that readers are forewarned that it is a retrospective reflection that aims to give some context to the event, to offer some reflective commentary on the sessions, and most of all to invite us to look forward, presenting some outcomes. In that sense, better an introduction than a conclusion.

The notion of a panel of speakers from across Christian traditions emerged through friendship. Matthew Holland, then the president of Utah Valley University, spent a term as a visiting scholar at Pembroke College Oxford; he was very good news and someone adept at initiating fruitful conversations across the University of Oxford and further afield. As a result, I was delighted to be part of a meeting of faith leaders exploring the plight of the Yazidis, where Elder Jeffrey R. Holland and Sister Patricia Holland joined Baroness Nicholson, Bishop Alastair Redfern, Lord Alton, and many others to be in solidarity with religious freedom in general and the Yazidis community in particular.

In conversations there, especially with Paul Kerry, two other concerns emerged:

1. How might we find ways of inspiring students and young people to take to heart a sense of vocation rather than merely an oppressive awareness of the large amount of student debt to be managed after they graduate? In other words, how could we unleash and energize a sense of vocation?

2. There was some reflection about the place of worship and college chaplaincy in higher education, in particular how—in the college chapels of Oxford and Cambridge—beautiful, aesthetic experiences are so often limited to fleeting emotions without encouraging a profound engagement with the substance of faith and its capacity to reach deeply into, and transform, the human condition. It was agreed that as marvelous as it was that literary and musical accomplishments celebrated human creativity and beauty, enabling the possibility of meaningful pastoral connections, the spontaneous desire to share the greatest gift, that of faith in a loving God worthy of the outpouring of such worship, was hard to convey and sometimes even avoided and treated as an embarrassment.

Inspiring Service

There thus seemed to be an important agenda, a real opportunity to begin to address these needs together, so bringing together a spectrum of people that were able to do something about it would be the best strategy. It was never going to be handed to us on a plate, we needed a significant amount of energy and a year and a half to imagine, plan, and provide for such an opportunity that might address these perceived needs. Paul Kerry’s organizational commitment and contagious enthusiasm never waned; the idea of a panel of speakers from the Church, academy, and public and political service was conceived.

This had the obvious advantage of addressing issues by looking to serve the world, looking outward together from a spectrum of faith perspectives in a mission that sought to communicate the value of all and to equip people to respond to needs boldly, collaboratively using diverse gifts, talents, energy, and personalities to transform our world. This notion was simple and clear. The academy is a proper environment to equip leaders to a model of profound service: leadership in Church, state, and local communities needs an integrity that measures power in the currency of service and values. The emergent idea of “Inspiring Service” sought to prompt people to reflect upon their experiences to equip a new generation to make a difference—contributing at a formative time in the life of students to use and cherish established, trusting relationships.

Thankfully this brought together four outstanding public servants—in state, academy, and Church—to commit to come to Oxford to meet students and others, formally at a panel and then informally over a stunningly large and inclusive banquet dinner, enabled by generous donations.

David Alton

Lord Alton began the series of presentations with an address that was as personal as it was carefully structured. He explored principles that must guide and inspire in the political world; he reflected upon an appropriate, reflective, and informed practice, before acknowledging in a poignant manner how it is personhood that inspires most powerfully. In a world where contemporary political life seems dominated by the charisma of personality, where there is significant evidence of popularist propaganda, Lord Alton urged a virtue ethic with these three dimensions—where values, honest reflection, and paradigms of personhood as character stand firmly against quick-fix techniques of an ethic rooted in personality or charisma.

Lord Alton cited examples from across his political career as the youngest-ever Liberal Councillor (aged twenty-one); he took a seat on Liverpool City Council in 1971. He was elected Member of Parliament as a member of the Liberal Party (later the Liberal Democrats) from 1979–97 and is currently a cross-bench peer in Britain’s upper house—the House of Lords. He managed to balance his integrity with the machinations of political life but would not compromise his commitment to human rights at every stage of human life—particularly aligning himself with the vulnerable. He is Professor of Citizenship at John Moores University in Liverpool and is committed to human rights, religious freedoms, and inspiring the International Young Leaders Network. His address and answers to the questions show that this is not a mere strategic or superficial veneer but his very life as a committed Catholic rooted in the social teaching of his own faith community. Alluding to Ghandi, Lord Alton himself demonstrated that integrity consists of ourselves being the change we want to see in our world and brought the personal plights of victims of religious oppression into the discussion with vigor and commitment.

Jeffrey R. Holland

Elder Holland brought his pastoral genius and his experience as president of Brigham Young University and a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, where he has had significant international leadership experience. He established that the character of the giver is laid bare in acts of service informed by committed understanding. Elder Holland’s address focused on the stories of the New Testament, particularly the story of the good Samaritan (Luke 10:36–37), to show the centrality of service within the Christian faith tradition—service extended to all regardless of differences in faith. Anything that gets in the way of caring for another, whether it is dressed up as business or a desire to not be made ritually unclean by an encounter, is exposed as a reluctance to be “doers of the word” (James 1:22) and disobedience to the requirements to give energy and attention empathetically to anyone; “if a brother or sister be naked, and destitute of daily food” (James 2:15), then words are not an adequate response to authentic philanthropy. He encouraged quiet and sustainable service rather than self-promotion and cited the Book of Mormon (Alma 34:17–28) as a witness and guide consistent with the teachings of the New Testament.

Elder Holland is a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, a church renowned for generously modeling the centrality of worship and community service; the imperative of giving sacrificially for humanitarian, welfare, and educational impact; a profound commitment to interfaith collaboration, advocacy, and solidarity, speaking for human rights and religious freedom; and support for international governance with finance and friendship. He acknowledged the traumatic experience of being a persecuted minority in the Church’s early days—in the state of Missouri and in the Roman Empire centuries ago—as significant motivation for this outward-looking service. Yet his own community’s accomplishments were not Elder Holland’s emphasis. Rather, he focused on the witness of scripture and the potential each person has (giving Saint Teresa of Calcutta as an example) to change the world and its future, offering an antidote to the widespread cynicism concerning the motivations and impact of serving and the unselfish use of human agency. The references to the New Testament illuminate a much-cited text from the Book of Mormon: 2 Nephi 25:23. This text is often cited by the Reformed tradition as evidence that the restored Church is one of works righteousness. Rather, this text urges profound accountability and may also be read as a text that heralds the victory of grace; despite the immensely inspiring examples of so many, salvation is rooted in God’s saving will and power. But the text may be read as highlighting this further, taking the phrase “that it is by grace that we are saved, after all we can do” as an affirmation of the power of God to bring victory and light out of all the dark deeds that humanity can—and does—do,[1] as well as exhorting our efforts to bear all the fruits of “love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance” (Galatians 5:22–23).

There is a rare mixture of energetic encouragement and realism in this contribution, illustrative of the particular contribution of this faith tradition to an informed and intelligent mission to the world—holding together a conviction in the action and sovereignty of God, with the imperative of moral volition and agency in all our faculties and energies.

Rowan Williams

Lord Williams’s experience in the academy, Church, British state, and world affairs is almost unique. Having been Regius Professor of Divinity in the University of Oxford (1986–91), and training people for ministry in the Anglican Church at Mirfield Theological College (1995–97) and Westcott House Cambridge (1997–86), he was consecrated to serve as bishop of Monmouth, thereafter archbishop of the church in Wales (2000–2002), and, between 2002 and 2012, he was Archbishop of Canterbury, Primate of all England, and First Among Equals of the worldwide Anglican communion of eighty-seven million people. After retiring from that role, he was appointed Master of Magdalene College Cambridge and life peer—as Baron Williams of Oystermouth—in 2013.

Lord Williams has thus not only managed to hold together very significant roles in different arenas but also reconciled his own clear convictions with an awareness that leadership was not about what he felt about a matter. Thus equipped, he managed, almost against all odds, to hold together very divergent theologies within the Anglican communion.

In his contribution, cooperation is core to his understanding of fulfilment and altruism in close relation: “The self-interest of wanting to be myself most fully is, paradoxically, interest in learning how I’m most free to serve and to nourish my neighbor.” Personal competition does not contribute to the accomplishment of the whole, and individualism even in team endeavors threatens the accomplishment of the best outcome through cooperative virtue. Lord Williams argues that this level of aspiration builds upon the three Ps of Lord Alton—principles, practice, and people—with the notion of prophecy, challenging idolatry and unfaithfulness. Prophecy can be challenging for us because it is often catastrophized or conceived of melodramatically. Lord Williams refers to the imperative, if uncomfortable, prophetic tradition of challenging the myths we live by. Such realistic prophecy is rooted in a fifth P—prose. In a world that prefers the poetic and creative and so easily undervalues the prosaic, hard, and routine, detailed work is imperative. It establishes the system to check another P—permission. In particular, part of pushing out into the deep and attempting responsible agency amid enormous and seemingly insoluble difficulties has to be risky. There has to be the permission to not be perfect, not to be God, the permission to fail as we address personal wounds and structural problems of our life in this world. The kind of human being we wish to be is intimately tangled up with the sort of opportunities we create for other human beings to flourish.

Frances Young

Professor Young’s presentation has characteristics of a Methodist testimony. But as she has been aware of the tendency of testimonies to bear witness to oneself, her presentation is executed in a sophisticated style. She owns the demands of the example of her father, Stanley Worrell, who also translated some very significant texts concerned with understanding early Christianity. For all that, Professor Young’s most significant self-designation is that of a “presbyter of the universal Church and one of John Wesley’s preachers”; in other words, holding together ministerial sacrifice and pedagogy. That priesthood is articulated as the leitmotif of service and echoes the awareness of the Eastern tradition, which she understands so well and which intuitively shapes her service: “Priesthood, for me,” wrote Alexander Elchaninov, “means the possibility of speaking with a full voice.”[2] Much of her life consists of holding apparently different things together creatively, the critic and the visionary, the scholar and the pastor, the mother and a leader of the academy, and speaking and acting convincingly and with balance—with a full voice. With this voice, her writings and preaching seek to reach out to those different from herself with an eye for connection. In a world where individuation and individualism are the measure of success, Professor Young urges a valuing of institutions as a means of requiring corporateness and cooperation and recovering community.

Emergence does not only refer to the enhanced capacities of slime mold under certain situations but also to what human beings are for: to grow into the stature of Christ together. In this way the disenchantments and disillusionments that we encounter, such as the response Professor Young received from an elder statesman of Methodism when she asked about what place there was in Methodism for a woman theologian. “None,” simply urged her on, as did the disincentivizing feedback from her classics professor at the end of her preliminary year as an undergraduate. She picked up C. K. Barrett’s commentary on the Greek text of the Gospel of John and “picked up and read.” In many ways, Professor Young’s encouragement is far from sentimental or emotive.

Eating Together

One of the most moving and authentic aspects of the evening, after drinks and conversations outside the lecture theatre, was the banquet dinner in Pembroke Hall for 150 people. Inevitably, Orthodox metropolitans, archbishops, professors, heads of Oxford colleges, bishops, archpriests, and the great and the good from university, Church, and city were present. Also present were people who had been invited because they lived in hostels or had spent many years living on the street, recovering from self-medications of various sorts—drugs, alcohol, and so forth—who were welcomed with generous, authentic affection, which recognized the dignity of all present. There were also local Church members and undergraduate and graduate students in attendance.

In a nutshell, it was a foretaste of the heavenly banquet and modeled what the professor of government and politics Stephen Whitefield styled “commensality”: being together around one table, being nourished together, sharing friendship, and modeling dignity together. This was a most moving and delightful celebration, which is not referred to here as there were no further formal contributions. The Master of Pembroke College welcomed all present and gratefully recalled her own ecumenical background—one steeped in Quaker and Methodist Church practice and Anglicanism at school—which, she appreciated, had steered her to nurture a sense of responsibility and service.

The inclusion of people with acknowledged addictions prompted a sensitivity and analytical self-awareness among many participants. One person reflected upon why he and so many people so often choose to live and die with addictions: because the dawning awareness of the pain of taking responsibility for actions and habits can simply feel too painful, too much to acknowledge and face, and the comfortably numb experience of an anaesthetized existence is easier. Eating together is rarely an occasion for such introspection, even the retelling of this story (with permission) makes the event sound rather intense. The fact was that eating together, even in the formal context of an Oxford college hall, was an opportunity for growth in honesty, personal integrity, and trust. The truth, as it were, made itself known in the breaking of bread.

Theological Investigations Concerning the Restored Gospel of Jesus Christ

Although the idea of a panel was conceived first, a persistent thought pursued us: whilst it is a duty and a joy to focus outwards in generosity, what about those things that are of first-order theological concern? What of those differences that have divided the Christian family across the ages, and in particular since the visions of the young Joseph Smith Jr. and the establishment of the restored Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints? Was a theological exploration and dialogue too much to hope for? A panel would allow common purpose, as can be seen from the papers delivered and the questions asked. Would a theological discussion highlight differences in approach? Indeed, was a theological investigation not bound to illustrate a fundamental difficulty in a community still open to the voice of living prophecy in its leadership and Church authority and therefore perhaps more cautious of theological enterprises? The assumption that theologians are somehow spiritual authorities as well as scholarly specialists has resulted in examples of assertiveness and disorder, which has led to division and a lack of cohesion in the history of the Church.

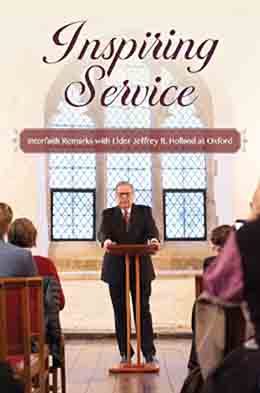

Thankfully, the Faculty of Theology and Religion put its name to such an initial investigation, and the University Church of St. Mary the Virgin hosted an engagement despite concerns on their behalf that this might be stepping back from scholarly or Anglican models of dissipated authority and freedom of scholarship. The presentation and discussion took place in a historically significant venue for theological discussion, indeed where Thomas Cranmer had been condemned and led to his execution outside in Broad Street in March 1556. Elder Jeffrey R. Holland, however, was sincerely and warmly welcomed as he made a humble and generous-minded address leading into a theological exploration of the restored gospel. This was, in fact, the first of the three events recorded here: on Thursday, 22 November, Oxford added another name to its historical Apostles and witnesses. From the first moment that Elder and Sister Holland arrived on the High Street, with Jacob, their guide from Salt Lake City, a sense of restored perspective and true affection and friendship was palpable and self-evident. This was not going to be a dry argument over minutiae of detail and disagreement but a recovery of life and joy in a spirit of joyful appreciation and open dialogue. Whilst this was not the initial primary purpose of a visit, it became a core and commanding event, which required minds and hearts and a willingness to listen, while being as true as possible to our experiences. Truthfulness of conversation strove to be the most inclusive dialogue—where truthfulness, fairness, and kindness moved to the most fruitful hopes, open in scope.

Elder Holland began his address to the academy at Oxford with some basic clarifications, which addressed some popular misconceptions and misrepresentations. He unapologetically outlined the beliefs of his community, including the vision of Joseph Smith Jr. in 1820, where Father and Son appeared in a glory that exceeded “the brightness of the sun” (Joseph Smith—History 1:16), but that vision , for all its wonder, was but a precursor of all that would unfold, including a visit to the oldest university in Britain to engage in a series of conversations with openness and hope.

Elder Holland explored the confusion and conflict that so often characterized the Latter-day Saint experience. It was a community thrusted into the experience of having an extermination order issued against them, which enflamed a persecuting mob.

What comes across is that these outcasts, though fleeing to the West amid great trauma, did not seek to withdraw from the world but took steps to become a US state and got involved in the social, political, and, of course, religious life of the young nation. That energetic commitment is evident in the fact that members of the Latter-day Saint community remain so publicly involved and, indeed, are in many ways the epitome of the American dream, finding faith and trust that—despite all initial appearances—there is something ultimately providential about the American Constitution. However, as The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints becomes more international, questions about accommodations of American culture to indigenous lifestyles have made the addressing issues of enculturation an important task.

Elder Holland, acutely aware of the trauma that the Christian churches have inflicted and suffered, was rightly cautious in his response to my question about recognition of the dignity and purposes of Joseph Smith Jr. among other Christian traditions. He would hope for that, but he had a firm grasp of reality. After all, the historic divisions since the Council of Chalcedon (AD 451), the Great Schism between Eastern and Western Christians (before AD 1054), and the Protestant Reformation and Catholic Counter-Reformations (ca. 1517 onwards) remain festering wounds in Christendom. Even recent attempts at rapprochement between Anglican and Methodist ministry and recognition in the UK have still failed.[3] Commitment to theological exploration and consultation would have to be miraculous to achieve where centuries of attempted reconciliation have failed.

Perhaps that has something to do with a can-do—or, better, a Babel—attitude rather than a humble one that brings everything together with an openness for this to be the work of God, rather than the reforming good ideas of human beings. Such a commitment is less another attempt at reformation than an openness to restoration. That happens only with our asking God to guide and sustain us. Timing—as in comedy and cooking—is everything, and it must be God’s timing rather than our pushing.

Dare we hope with Elder Holland? Could it possibly be that these problematic days for the mainstream churches be the very time when God may act? As Eastern Christians gather for the Orthodox Liturgy, a deacon says to the presiding priest, “Now it is time for the Lord to act” (compare Psalm 119:126); it is not our action, though it requires of us both volition and a willingness not to get in the way. “Inspiring Service” and the events around it hold out before us the imperative of a near-impossible task. John Donne brings us close to an inclusive vision that can only be the work of the infinite atoning power of Jesus Christ: “For all this separation, Christ Jesus is amongst us all, and in His time, will breake downe the wall too, these differences amongst Christians, and make us glad of that name, the name of Christians, without affecting ourselves, or inflicting upon others, the names of envy, and subdivision.”[4]

Outcomes

The outcomes from this encounter certainly remain fruitful and promise a harvest still to be reaped. Elder Holland was more than good with his word of inviting me to Utah, and a first visit to Salt Lake City followed. It focused on Temple Square, the general conference of spring 2019, the work and inspiring service of Welfare Square, and the academic work of Brigham Young University—in particular its Religious Studies Center and the Neal A. Maxwell Institute for Religious Scholarship.

As wonderful as these outcomes were for me personally, there was—and remains—a sense that these opportunities are far too significant (and far too enormous!) to be mine alone. Further visits have been planned, participation in conferences considering the nature of chaplaincy from various faith perspectives have been discussed, and proposed scholarly enterprises in Provo, Oxford, and even mainland Europe that engage in scholarship from a wide spectrum of traditions are to be worked at.

Although it is a personal privilege to form relationships in the service of God and address the world’s needs, it is too small a thing considering the responsibilities we bear for our own faith communities: to encourage peoples to “travel” together is imperative and foundational work. To enable this work is a burning priority, whether we see an outcome in our days on earth or not.

Integrity is imperative; every one of us has a personal responsibility to engage with an eye to being an ambassador for Christ and the community of which we are a part. That clarity of purpose cannot seek to feign but to engender friendships, encouraging faith and service from the perspective of becoming a committed auxiliary, not of pretending to be a member of each other’s church.[5]

In my conversation with Elder Holland during the questions-and-answer session, I referred to the disappointing ruling in Leo XIII’s apostolic letter Apostolicae Curae (1896) for Anglo-Catholics. It judged Anglican orders to be “absolutely null and utterly void.” In fact, it merely said that an Anglican priest is not a (Roman) Catholic priest. The Anglican Church really does not hold a coherent view of priesthood across the spectrum of its own groupings, but for all the pain of its clarity, Leo XIII’s letter does not deny Anglican ministry and service. Real discussion faces uncomfortable histories and difficult categories; to commit ourselves to this theological journey will mean traveling a steep and narrow path and bearing the pain so that it, and we, might be transformed.

Thus, whilst we may dare to harbor hopes of unity and respect—such as the representation of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints on the World Council of Churches as observers—of an embrace of sobornost (ecumenicity), or the universal recognition of baptism and appreciation of diversity—those worthy aspirations are not why we must be committed to deeper understanding. Elder Holland insisted upon anchoring our energies upon something at once more straightforward and demanding: “The first obligation forever and ever, is that we love God and love each other. If we could remember that, begin with that, and do that, I can’t really imagine a serious conversation getting into trouble.”

Worship: “Nine Lessons and Carols”

The conclusion of weekly services in the Damon Wells Chapel in Pembroke College Oxford on the last Sunday of Michaelmas term is the traditional “Nine Lessons and Carols” service, originating in King’s College, Cambridge, but applied to Pembroke’s royal and religious foundation. Readings from the Old and New Testaments point to the person of Jesus Christ and the significance of His birth. At the conclusion of their visit to Oxford, Elder and Sister Holland attended this service before a formal “High Table” in Pembroke Hall.

The chapel, seating a maximum of 110 people, contained 156 people that night. The choir sang a mixture of anthems, and the congregation joined in with carols. Nine readers from the college read the lessons, and, at the end, Elder Holland gave a poignant but simple address, which is printed in its entirety in this book.

Had people expected a cheerful, plastic, prepacked, nonchalant address, they would have been profoundly disappointed. The words are printed in this book, but it was the humble, engaging manner in which they were delivered that grasped the attention of people’s minds and hearts.

One guest was a retired Fellow whose wife of very many years had recently died. He telephoned me afterwards to say that he hadn’t quite known what to expect, but the way Elder Holland drew on personal pain at this season could not have been more appropriate for him: it brought him comfort (the etymological root of that is strengthening). There was neither a forced smile in sight nor an expectation to be cheerful. Rather, there was an embracing humanity and solidarity at a time of loss and pain.

A member of the choir who describes herself as a “post-Christian feminist” remarked that although she did not share his faith, she saw in Elder Holland a pastor par excellence—a very humane and endearing man, who drew close to people with authenticity. Elder Holland’s address is inclusive and encouraging without abandoning the invitation that goes with proclaiming the Good News; it fit the subdued and gently lit environment of a college chapel. Elder Holland appeared as someone as prone to human joys and pains and weakness as anyone else, and because of this, he drew close enough to be trusted. He did this while witnessing that he had been led into life and was therefore worth following. Elder Holland has the gift of using beautifully crafted prose, but he offered a means of preaching the gospel without the din of words. He humbly walked the path that the families of Christian communities must walk, together, with gentle faith, joyful hope, and authentic love.

Conclusions—Ambassadors of Love

In the panel presentations we see that testimony given from one life to another is most moving and compelling. Such communication faces disenchantment—even a negative response to Frances Young’s question about women theologians became a challenging and creative no to her, as did her wait for ordination within her tradition until the time was right.

It is easy to be impatient and to wish to travel by ourselves to an ideal destination. Dietrich Bonhoeffer is right to remind us that when we put our personal ideas above given values held by a community, we become a despiser of the community of which we are a part because it cannot keep up or measure up to our idea of perfection. “It means, first, that a Christian needs others because of Jesus Christ. It means, second, that a Christian comes to others only through Jesus Christ. It means, third, that in Jesus Christ we have been chosen from eternity, accepted in time, and united for eternity. . . . He who loves his dream of a community more than the Christian community itself becomes a destroyer of the latter, even though his personal intentions may be ever so honest and earnest and sacrificial.”[6] It is also easy to naively imagine that good relationships and theological engagement and listening are not already happening. There are wonderful examples of good relationships between the churches. Yet there is something especially significant about the events in Oxford, which brought together the Oxford academy with that of Utah and put in one line representatives of Roman Catholic, Anglican, Restorationist, and Methodist Christian traditions. Together, they looked at questions and needs of the world. There are different models of authority, from the Catholic hierarchy, to the dissipated model of Anglican and Methodist authority, to a church that has living prophets, seers, and revelators—of which Elder Holland is one.

There are therefore significant questions worthy of exploration that became clear, but these emerged in an environment of profound friendship and love—embodying a sense of God’s mission to the world, rather than competing denominations diminishing each other.

It is this mode of dialogue, in real Christian love, that there is a fundamentally hopeful invitation to explore things that on the surface would appear to be areas of contradiction and conflict, but which—as illustrated by Professor Young—are a possibility for extraordinary service and achievement as one connected web.

With the experience of these series of events still alive in Oxford, it is very easy to be overoptimistic, and we know that with that comes disillusionment and despair. Elder Holland’s response to the question about a wider appreciation of Joseph Smith Jr. was helpful here: he would long for that, but he is not unrealistic about the struggle, the steep trail of faith, that lies ahead on that route. The Christian Church cannot reform itself; a restoration which is nothing other than the work of God is required. If it is of God, it is also too important to rush. Impatience often rejects the commitment to make changes slowly for the good of all. The events in Oxford leave questions and intuitions.

The work of theological and spiritual engagement with one another in God’s mission to the world is too important just to be a marginal or eccentric scholarly interest. This engagement has to be on behalf of and offered to our communities. The experience has stirred in me a desire to dedicate scholarship, devotion, and myself to the path of reconciliation—for the glory of God, the good of the Church, and the needs of the world that God loves. But it cannot merely be a personal journey; it is a long and no doubt problematic path to be traveled with our communities.

Anything less is too cautious and too unadventurous. Might it even be that Joseph Smith Jr.’s experience is a shocking surprise to the Christian Church still? That asking how to proceed and being met by the purposeful, redemptive presence of the Heavenly Father through the life and ministry of His Son and through the Holy Ghost sharing that divine nature might restore the divine dignity of the children of God in our flesh and in our day? Might what has been so misconstrued and misunderstood as diminution yet be the liberating truth that the God of earth and heaven desires to draw close to each person and that the talents and energies we have need to address this?

The events of “Inspiring Service,” through the many contributions, invite us to travel beyond brittle conceptions of our self into the whole history of humanity, with the mission of redeeming by friendship and service. That can only ever be accomplished as an act of love.

In heaven, where we shall know God, there may be no use of faith;

In heaven, where we shall see God, there may be no use of hope;

But in heaven, where God the Father, and the Son, love one another in the Holy Ghost, the bond of charity shall everlastingly unite us together.[7]

Notes

[1] Some read “after all that we can do” in a negative sense—as in after all that human beings are capable of doing, and have done through history, God’s grace will accomplish salvation. However, it is clear that the positive encouragement of this verse has priority—urging us to do all that we can but remain humble even in that enthusiasm, to see the work of God as sovereign.

[2] Alexander Elchaninov, The Diary of a Russian Priest (London: Faber & Faber, 1973), 18.

[3] The Anglican Methodist reunion scheme failed in 1972 and has consistently failed to be approved, even in the General Synod of the Church of England in the summer of 2019. “General Synod: Methodist Union Legislation a Bridge too Far for Now,” Church Times, 12 July 2019, https://

[4] John Donne, Sermons II.3.615–19, in One Equall Light: An Anthology of the Writings of John Donne, comp. and ed. John Moses (Norwich, UK: Canterbury Press, 2003), 35.

[5] Compare Robert L. Millet, “God Grants unto All Nations,” in the 2019 conference of the Society of Mormon Philosophers and Theologians, University of Utah, 15 March 2019, 4–5 (typescript): “It does not mean that God disapproves of or rejects all that devoted seekers after truth are teaching or doing, where their heart is, and what they hope to accomplish in the religious world. ‘God, the Father of us all,’ President Ezra Taft Benson said, ‘uses the men of the earth, especially good men, to accomplish his purposes. It has been true in the past, it is true today, it will be true in the future.’ President Benson then quoted the following from a conference address delivered by Elder Orson F. Whitney in 1928: ‘Perhaps the Lord needs such men on the outside of His Church to help it along. They are among its auxiliaries, and can do more good for the cause where the Lord has placed them, than anywhere else.’ Now, note this particularly poignant message: ‘God is using more than one people for the accomplishment of His great and marvelous work. The Latter-day Saints cannot do it all. It is too vast, too arduous for any one people.’”

[6] Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Life Together, trans. John W. Doberstein (London: SCM Press, 1985), 10–11, 15–16.

[7] John Donne, Sermons II.10.15–19, in Moses, One Equall Light, 44.