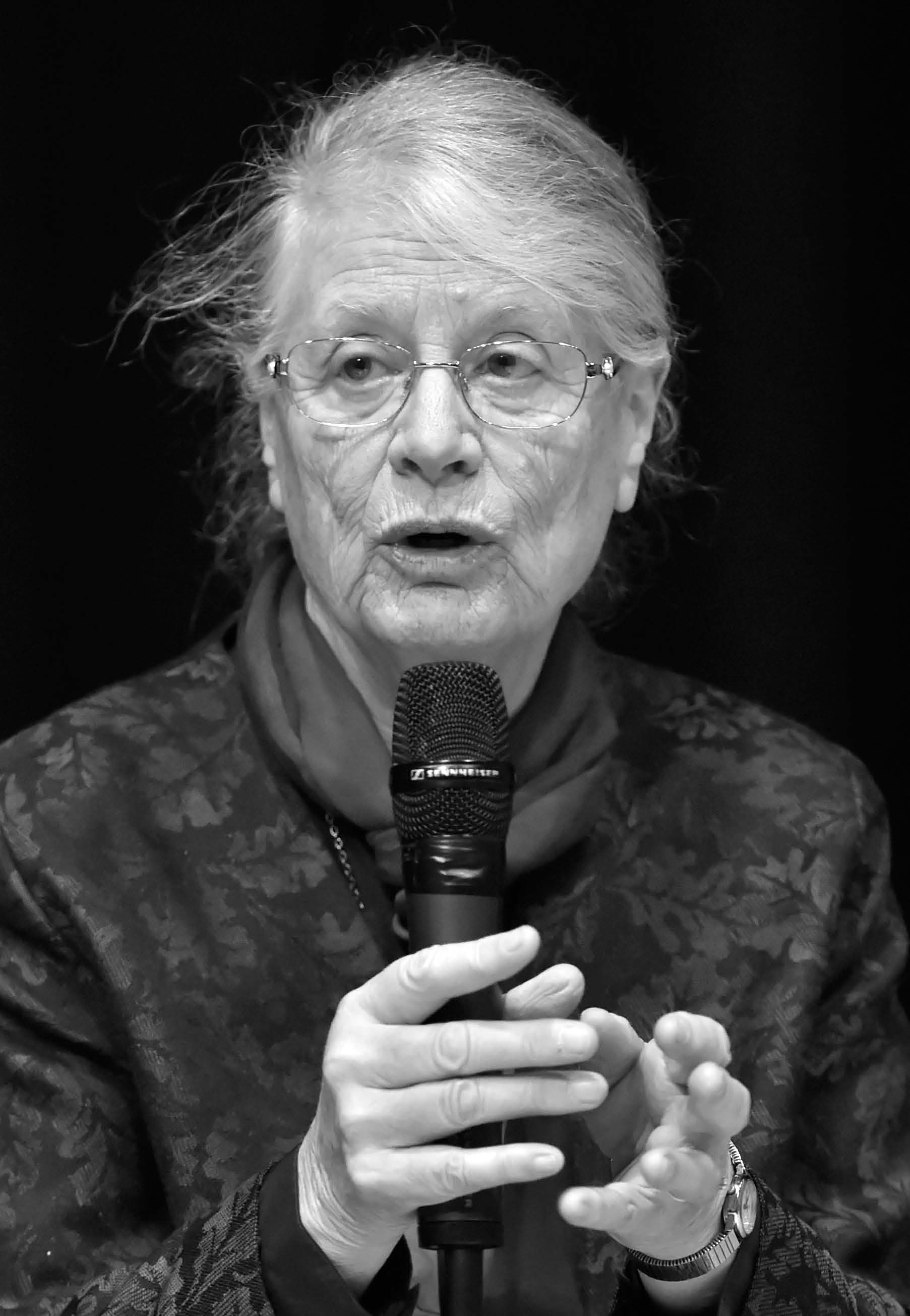

Frances Young

Frances Young

Frances Young, in Inspiring Service, ed. Andrew Teal (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 47–54.

Reverend Frances Young

Reverend Frances Young

In December 1974, at a secret location, some churchmen from Northern Ireland who were led by a Methodist minister met with the Provisional IRA Army Council to explore the possibility of a ceasefire. The IRA men arrived at a hotel in the remote village of Feakle, looked around, and asked the Methodist minister, “Who’s that over there? He looks like an English colonel.”

“He’s the former headmaster of the Methodist College in Belfast,” was the reply. “Would it help if I tell you he was a pacifist in the war?” The next morning it was him whom the IRA men accepted as chair of the talks.

Stanley Worrall was indeed an Englishman. He’d been headhunted in the early 1960s—the Methodist governors wanted a Methodist headmaster for their large coeducational grammar school. When he retired, he and his wife had stayed in Northern Ireland to contribute to public service and community work of various kinds. He was chair of the Northern Ireland Arts Council and he served on the governing bodies of the Stranmillis (a teacher-training college), the then new University of Ulster at Coleraine, the Paddysburn Mental Hospital, and RTÉ (that’s the Irish equivalent of the BBC) in Dublin.

He was my father. Most of my life I’ve recognized how living up to him shaped my career. He was an embodiment of the fact that Christianity is an intellectual tradition worthy of serious academic engagement and capable of making sense of life, the universe, and everything. He was a committed educationalist, passionate about forming the minds of young people. But I’m only now recognizing that it was his example of Christian commitment to public service that explains some of the odd decisions I made in the latter stages of my career.

When my family moved to Northern Ireland, I was already at university. I was about to take my classics finals, and I was trying to find ways of fulfilling a call to go on to study theology, to use my competence in Greek to study the New Testament. One Sunday, an elder statesman of Methodism came to address the Student Methodist Society. I asked him what place there was in Methodism for a woman theologian. “None,” he said.

Nothing daunted, I went for my degree in theology. But then my life took an unexpected course: I married a scientist who was following a career in universities, and it made sense to follow him. In due time we both landed jobs at the University of Birmingham. Meanwhile, long before the Anglicans, the Methodist Church had decided to ordain women and, somewhat out of the blue, in midlife, I had another call. Sometimes I speak, tongue in cheek, of my Damascus road experience, but that’s another story.

So in 1984 I was ordained as a minister with permission to continue teaching theology at the university. Teaching has always been important to me—passing on what I’ve received and helping people to understand, to learn, to think. But my identity truly lies in being “a presbyter of the universal Church and one of John Wesley’s preachers,” as conveyed to me at my ordination retreat in 1984. There is nothing more profound and humbling as offering people what they need for their inner spiritual health, for their worship—placing the eucharistic elements in people’s hands, speaking the word of God, and offering blessing.

So, why on earth did I end up being a manager—head of department, Dean of Faculty, and Pro-Vice-Chancellor of the university? What were those years about? The question has never completely gone away. After all, most academics just want to get on with research and hate administration. Was it just ambition, nothing to do with—perhaps indeed contrary to—my Christian commitment?

It certainly was a response to the moral pressure of being the first woman to hold those positions: if one wasn’t prepared to do it, how would things ever change?

But my ordination had taken place two years before; how did all that relate to ministry? At an overtly secular university, how could Christian commitment be expressed? What was I doing struggling with the frustrations of university politics? Practically everything I managed to achieve back then has by now been overtaken. There’s no permanent legacy in running things day to day.

But I’m beginning to discern my debt to my father here too. The proper running of institutions is vitally important to society and crucial to facilitating people’s flourishing. The endeavour to make the world a better place lies at the heart of the affirmation that this is God’s world.

So now, in my own retirement, all that experience is feeding into another institutional commitment. I’m an elected public governor of the Birmingham Community Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust. The management board is accountable to us—the Council of Governors, volunteers who represent the public. And yes—it’s frustratingly difficult to see what difference we make, the endless papers to be read, the data to be digested, and the meetings to go to don’t always thrill me, to say the least. But the work of the trust really matters, and in using the skills I’ve acquired to act as a critical friend, I am giving back. For my own family has been, and doubtless will continue to be, beneficiaries of the services provided.

Which brings me to another crucial influence on who I am, what I think, what and who matters to me, and what I do, namely, my firstborn son, Arthur. Now fifty-one years old, he’s entirely dependent on carers, has no self-help skills, no independent mobility, no language, and very little comprehension. We cared for him for forty-five years; he’s now in residential care locally. The services of the NHS Community Trust have been, and still are, important in maintaining his life—the district nurses, the wheelchair service, physiotherapy, speech and language therapy (he has no language, but they provide the advice on his feeding and drinking), community dentistry, and, when he lived with us, the short-term respite service. That was our lifeline!

I could easily be distracted into talking about how I discovered the most fundamental human values in caring for Arthur—love, joy, peace, patience, kindness, faithfulness; Saint Paul lists nine of them and calls them the fruits of the Spirit (Galatians 5:22). Or I could tell how I found that it’s in the struggles and darkness of human experience that one discovers the most meaningful gifts—sense and depth, grace and simplicity. But in this context Arthur’s importance is in opening me up to people utterly different from myself and discovering how much the most unlikely people have to contribute.

All that was reinforced by my relationship with Jean Vanier, the founder of the L’Arche communities. From the organization’s Roman Catholic roots, it is now an ecumenical, even multifaith, international organization, where barriers between people of utterly different backgrounds are dissolved by common commitment to those with learning disabilities, in the United States they call them developmental disabilities. Spiritual growth is discovered not only in the ups and downs of community life but in mutual relationships. That’s the crucial point: so much service and charity work is top-down and patronizing, but at the heart of Jean Vanier’s vision is the mutuality discovered in caring for those who cannot care for themselves: the assistants receiving unexpected gifts from those they assist, discovering things about themselves through the “other,” the stranger, the one who’s different.

Maybe that will strike you as a rather hackneyed, postmodern observation. But it’s a truth I’ve also discovered in the multiethnic, inner-city churches I’ve served, where Arthur has always been part of my ministry.

And besides that, the discovery of this truth also came through the experience I gained from teaching theology to the pastors of black-led churches—an extramural program set up by the University of Birmingham back in the 1980s. Oh yes, we began with profoundly different views of the Bible; from an academic perspective, they read scripture with a naive literalism. Yet their profound faith and hope, love and joy changed me. As a somewhat shy introvert, it was not always easy for me to reach out to those so different from myself, but I found a new freedom and, most important of all, discovered that you give people dignity by receiving from them. The most extraordinary moment came when some visitors to the course challenged the biblical criticism I was teaching, and the class leapt to my defense: “There are contradictions and difficulties in the Bible,” they said, “and Frances is showing us how to understand them.” We had grown together.

Preparing this for you has been important for my own self-understanding (and I’m afraid it has turned out to be something of a personal testimony—a good Methodist tradition, of course). By tradition, Methodists are activists. I’ve spent much of my life feeling guilty that I’ve done so little good in world; I’ve not fed the hungry, healed the sick, welcomed the homeless, or visited those in prison. I’ve been one of a lucky generation: able to pursue my interests and, as a woman, have both a family and a career; I’ve never had to worry about mortgages or money or argue about them with my husband, without whose support and partnership I’d never have become what I am. He took early retirement to become Arthur’s principal carer and treasurer of four different disability charities!

Yes, I’ve been lucky—so much luckier than my frustrated mother. Yet she modeled a constant search for vocation and a commitment to helping others, to the Methodist Church’s healing ministry and to Girl Guides. And you have pushed me into reassessing my past. Through acknowledging even more comprehensively my need to live up to my father, I’ve reclaimed the importance of public service to secular institutions and grasped more of its theological grounding.

Reading the earliest Christian documents, both in and beyond the New Testament, what is striking is the claim of this little, underground (sometimes persecuted) group that their God is the God of the whole created order and that everybody is accountable to this God, who actually sees into the heart, knows the secrets of inner motivations, and expects everyone to do good, to be generous, and to live honorable lives, accepting the authority of human institutions: the pagan emperor himself was appointed by this one and only God to ensure justice and peace.

At this point in history, such subservience appears highly problematic, doesn’t it? But, for all our current individualism, we are social animals; we need each other, and society still requires well-run institutions to govern competing interests, to ensure peace and justice, and to foster human flourishing in body, mind, and spirit.

The theological undergirding of public service is surely a commitment to the fact that this is God’s world, despite the way things seem. It’s been said that the Christian doctrine of sin (meaning not simply sex or individual misdemeanours, but rather the way human affairs in general keep going somewhat pear-shaped) is the only empirically grounded doctrine! Christian faith proclaims that God has taken action in Jesus Christ to put things right and calls us to play our part in that process. That’s why commitment to making the world a better place lies at the heart of Christian service and why service means something other than imposing top-down control. It’s no accident that humility and counting others more worthy than oneself has such prominence in the New Testament. We need people who are receptive to others to be the servants of all in our public life.