David Alton

David Alton

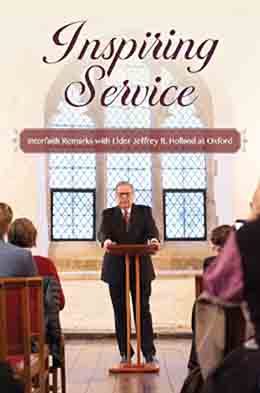

David Alton, in Inspiring Service, ed. Andrew Teal (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 11–26.

Lord David Alton

Lord David Alton

Receiving an invitation from Andrew Teal is a bit like a three-line whip—Not least because of the debt I owe him for the kindness and inspiration he showed my daughter when she was here as a student. I have drawn the short straw for alphabetical reasons, so I’m the warm-up act for my colleagues who will follow.

Only in Britain would the words community service be turned into a punishment to be dispensed by the courts. The principle of serving others is a central tenet of citizenship; for Christians, it is at the very heart of the gospel; the service of others changes lives, changes society, and changes us—all for the better. It is the animating principle for public life par excellence.

It draws its force from the recognition that every human person (every soul) is worth more than the whole of the rest of the created order—each unique, each a person made in the image and likeness of God, each with inherent dignity and worth, and each made to express themselves as moral beings that grow in love and charity through their own particular gifts.

I have assumed that when Andrew sent me the examination topic, “Inspiring Service—Discuss,” he would want me to reflect on the almost forty years spent in Parliament and the eight years before that when I served an inner-city neighborhood in Liverpool, where half the homes had no inside sanitation and where I was elected, while I was a final-year student, as a city councilor.

Let me follow the example of the Romans who divided Gaul into three parts: firstly, what principles should inspire service through politics; secondly, how faith should inspire us to serve; and thirdly, who has inspired me—principles, practice, people.

What Principles Should Inspire Service through Politics?

Every day that I am at Westminster, I walk through Westminster Hall, where Parliament first met in 1265, where Thomas More and Charles I were tried, and where, in 1965, Winston Churchill was laid in state.

As a young boy, along with millions of others, I walked past Churchill’s coffin. He has been lionized as the man who saved democracy. Yet Churchill had a realistic view of democracy and politics, once saying, “Many forms of Government have been tried, and will be tried in this world of sin and woe. No one pretends that democracy is perfect or all-wise. Indeed, it has been said that democracy is the worst form of Government except for all those other forms that have been tried from time to time.”[1]

This least “worst form of Government” in this “world of sin and woe”—impaired but always preferable to dictatorship or totalitarianism—cannot function without virtue, commonly held values, and a belief in serving the nation rather than serving yourself or serving sectional interests.

In 1979, elected to the House of Commons, I was privileged to serve alongside the last members who had seen active service in the Second World War and who had served alongside Churchill in the House. Overwhelmingly, regardless of their party allegiances, they believed in public service and the principle of duty.

The alternative approach to political service can be found in Niccolò Machiavelli’s The Prince. He tells us that the ruler should be prepared to choose evil as the price of power and not hesitate to deceive. Mercifully, he didn’t have access to Twitter. Machiavelli despised many traditional Christian beliefs and turned words such as virtue on their heads, believing that real virtue emanated from the pursuit of ambition, glory, and power.

And of course, this represented a fundamental break with Thomas Aquinas, medieval scholasticism, and the Aristotelian belief in the principle and pursuit of virtue. Aristotle had a high view of the polis. He insisted that “we are not solitary pieces in a game of chequers” but all players in a common life and that “aidos—shame—would attach to the citizens who refused to play their part.”[2] Aristotle warned that “he that is incapable of society, or so complete in himself as not to want it, makes no part of a city, as a beast or a god.”[3] Aquinas echoed Aristotle in extolling the cardinal virtues of prudence, justice, temperance, and courage. This inspired belief in the value of virtuous service is captured in many societies and systems of belief.

My mother was a native Irish speaker from the west of Ireland. On the wall of the council flat where I grew up, we had some words in Irish which, translated, said, “It is in the shelter of each other’s lives that the people live.”

We lived next door to a Jewish lady, Sadie Moonshine, who would have been familiar with Hillel’s admonition “If I’m not for myself who will be? But if I am only for myself, who am I?”[4]

Nelson Mandela often reflected on the idea of Ubuntu—a person is a person because of other people. Archbishop Desmond Tutu explained, “A person with Ubuntu is open and available to others . . . and is diminished when others are humiliated or diminished, when others are tortured or oppressed.”[5] Ubuntu is only possible in a person with this common good mentality, a mentality at odds with our cold, calculated, utilitarian, social mores.

Public policy can never be legitimate if it does not serve and promote the flourishing of each unique, created person and withstand the violation of a minority or even a single individual because there can be no common good that does not respect our equal worth and dignity first.

We don’t exist, then, in isolation; we are not simply individuals who, in a parody of the gospel, think it is okay to “do unto others before they do you” and demand bigger, faster, better, more and the absolute right to choose while being oblivious to the consequences on others.

The great nineteenth-century idealist and exponent of ethical liberalism, and indeed of Oxford, City Councilor Thomas Hill Green was right when he said, “If the idea of the community of good for all men has even now little influence, the reason is that we identify the good too little with good character and too much with good things.”[6]

The concept that we should place ourselves at the service of others—at the service of the common good and at the service of the weakest, the poorest, the most vulnerable—gives form and expression to the desire of the virtuous citizen to generously and altruistically use their privileges and their talents in the inspired service of others.

But, friends, a snapshot of contemporary Britain shows what happens when we stop looking out for others, where toxic loneliness replaces family and community cohesion and too many feel like losers even when they are thought to be winners in purely material terms and where without shared values and rules, stable relationships, a sense of duty, and a willingness to serve others, we too easily shrink into merely atomized individuals, invariably unhappy, unfulfilled, and often alone.

Whether we like it or not, we come from a community, with all its faults and failings, and each of us, with all our own faults and failings, do have some gift to return. That’s how it should be.

But too often, regrettabl, public service through politics has been replaced by a self-serving and self-regarding form of careerism too often dominated by attempts to climb Disraeli’s greasy pole; too often characterized by growing intolerance and toxicity, reflected even at universities like this one, with the disallowance of platforming alternative views; too often governed by narrow ideologies, increasingly disconnected from communities, creating a vacuum into which organizations with extreme and inflammatory views are able to enter with ease.

Gandhi warned of the danger of becoming disconnected: “To forget how to dig the earth and to tend the soil is to forget ourselves,” telling us, “You must be the change you want to see in the world.”[7]

If we want to change the world, we need to change our nation; if we want to change our nation, we have to change our communities; if we want to change our communities, we change our families; and if we want to change our families, we have to change ourselves. Change doesn’t come about by itself; it comes through active participation and voluntary service. Sometimes that will be through elected office. Desmond Tutu, an African Anglican bishop, once said that politics is not a dirty business—just that some of the players have dirty hands, and he was right. Politics are ultimately only as good as the people who are engaged with them. And what happens when democracy is hollowed out?

The year 2017 saw the centenary of the Bolshevik Revolution, which paved the way for totalitarianism, social engineering, state terror, and mass murder, leaving a legacy of prison camps and unmarked graves. Thirty million people were executed, starved to death, or perished in labor camps in what was the bloodiest century in human history, with the loss of a hundred million lives. The century began with the Armenian genocide and culminated in the Holocaust and the depredations of the four mass murderers of the twentieth century: Mao, Stalin, Hitler, and Pol Pot.

Our former chief rabbi Jonathan Sacks reminds us, “Do not ask ‘Where was God at Auschwitz?’, ask, ‘Where was man?’”[8] The great Protestant theologian Dietrich Bonhoeffer warned each of us, “Not to speak is to speak; and not to act is to act.”[9]

Does Faith Inspire Us to Serve?

If all of this should guide us into political service, what does the Christian faith say to us?

Every person uniquely reflects the divine likeness, and for that reason alone we are required to uphold the dignity of each. In rendering unto Caesar, we don’t need to stop seeing everything through the lens of our faith.

When Churchill, who was not known for religious ardor, was once described as “a pillar of the church,” he corrected the speaker by interjecting that he was “not a pillar, but a buttress, supporting it from outside.”[10] And why? Churchill insisted, “The flame of Christian ethics is still our highest guide. . . . Only by bringing it into perfect application can we hope to solve for ourselves the problems of this world and not of this world alone.”[11] Churchill understood that the least “worst form of government” was dependent on Judeo-Christian values and ideals.

And if he was our greatest twentieth-century prime minister, surely Mr. William Ewart Gladstone was the greatest of the nineteenth century. Gladstone said this: “As to its politics, this country has much less, I think, to fear than to hope; unless through a corruption of its religion—against which, as Conservative or Liberal, I can perhaps say I have striven all my life.”[12] This is a sentiment which surely William Wilberforce, Lord Shaftesbury, Keir Hardie, and many other significant political figures would have conferred. In an inspiring letter, in fact the last he wrote, John Wesley told Wilberforce to use all his political skills to end slavery and to fight for human dignity, warning that “unless the divine power has raised you us to be as Athanasius contra mundum, I see not how you can go through your glorious enterprise in opposing that execrable villainy which is the scandal of religion, of England, and of human nature. Unless God has raised you up for this very thing, you will be worn out by the opposition of men and devils. But if God be for you, who can be against you? Are all of them together stronger than God? O be not weary of well doing! Go on, in the name of God and in the power of his might, till even American slavery (the vilest that ever saw the sun) shall vanish away before it.”[13] In all our faith traditions, we need to encourage greater emphasis, then, on an outpouring of service, including into politics. And what a blessing this can be. After all, 84 percent of the world’s population is religious.

From the Catholic tradition, where do I look for inspiration?

Well, John Henry Newman told his Oxford students to love their country and to serve the nation: “We are not born,” he said, “for ourselves, but for our kind, for our neighbours, for our country: it is but selfishness, indolence, a perverse fastidiousness, an unmanliness, and no virtue or praise, to bury our talent in a napkin.”[14]

Jacques Maritain, in Integral Humanism, asserted, “Christianity taught men that love is worth more than intelligence,”[15] insisting that Christianity may not need democracy to survive but that democracy needs Christianity if it is to thrive.

Democracy isn’t a spectator sport; Christians must offer servant leadership and fearlessly champion human dignity. G. K. Chesterton, writing in 1930, said, “When people begin to ignore human dignity, it will not be long before they begin to ignore human rights.”[16]

The Church fathers say the same, declaring in 1965 in Dignitatis Humanae that “religious freedom therefore ought to have this further purpose and aim, namely, that men may come to act with greater responsibility in fulfilling their duties in community life.”[17] In Veritatis Splendor, in 1993, they state, “As history demonstrates, a democracy without values easily turns into an open or thinly disguised totalitarianism.”[18] In 2009 in Caritas in Veritate, referred to earlier, it declares, “Many people . . . are concerned only with their rights. . . . Hence it is important to call for a renewed reflection on how rights presuppose duties, if they are not to become mere license.”[19] And Pope Francis, in 2016, in The Name of God Is Mercy, rebukes those who neglect love, using the metaphor of the church as a field hospital rather than a perfected society—where we who are the most wounded can encounter Christian love in action.[20] Inspiring and channeling adherents into public service is then transformative of individuals and society.

Who Has Inspired Me?

So much for the principles and practice. What about the people?

Never forget the local councilors, the political activists, and the backroom people who organize elections and the unsung and unseen heroes who spend hour after hour in advice centers and hospitals dealing with day-to-day crises and problems facing constituents and also demonstrating that they genuinely care about individuals.

I have a poster on my study wall that says “God so loved the world, he did not send a committee.” Part of what you have to do if you’re going to be involved in any kind of service is to navigate committees and spend hours and hours in them.

In a great book called Two Cheers for Democracy, E. M. Forster described a liberal who has found liberalism crumbling beneath him but insisted that the idiosyncratic, bloody-minded, back-bench member of Parliament who gets some minor injustice put right is the justification of our imperfect system of democracy.[21]

Well, inspired political service can put right more than minor injustices. I have mentioned Wilberforce, who with Clarkson, the Quaker ladies, and others campaigned for forty years against the slave trade. And think of heroes like Dietrich Bonhoeffer or Maximilian Kolbe, whose stand against Nazism cost them their lives.

But there are countless others, too, who should inspire us to use the gifts we have been given. As a teenager, I was inspired by Robert Kennedy and Dr. Martin Luther King—both murdered for their beliefs. Kennedy insisted that “each of us can work to change a small portion of events.”[22]

Last month I was in Pakistan raising the case of Asia Bibi—an illiterate woman who worked in the fields nine years ago and was given a death sentence for so-called, alleged blasphemy. And recently you will have read she has been acquitted of those charges but is still not free to leave that country.

In 2011, after championing her case, the Christian minister for minorities, Shahbaz Bhatti, and the Muslim governor of the Punjab, Salmaan Taseer, were both murdered: Bhatti said this just months before his death: “I know the meaning of the Cross. I am following the Cross, and I am ready to die for a cause.”[23]

Esther famously said, “If I perish, I perish,” for “how can I endure to see the evil that shall come unto my people?” (Esther 4:16; 8:6).

Asia Bibi, like Bhatti, like Salmaan Taseer, like Esther, came into the world, again in words from the book of Esther, “for such a time as this” (Esther 4:14). Shahbaz Bhatti’s murderers have never been brought to justice, whilst last year a mob of 1,200 people forced two children to watch as their Christian parents were burned alive. Think, too, of the twenty-one Coptic Christians who, in 2015, in the moment of their barbaric execution by ISIS were repeating the words “Lord Jesus Christ,” or of the two North Korean women who appeared before a committee chair and described egregious and brutal violations of human rights.

Friends, when you encounter people facing murder, beheadings, rape, terror, and intimidation, you can feel overawed but inspired too.

These examples and these stories are pointless unless they inspire us to do something about it—to put our array of amazing gifts and privileges at the service of others.

In these three points—principles, addressing the principles that should inspire service through politics; practice, stating how faith should inspire us to serve; and people, mentioning some of those who have inspired me—I hope that I have at least done a little bit of justice to Andrew’s challenge to reflect tonight on inspiring service. Thank you.

Notes

[1] Winston Churchill, “The Worst Form of Government,” International Churchill Society, https://

[2] David Alton, review of The Political Animal: An Anatomy, by Jeremy Paxman, Third Way 26, no. 2 (March 2003): 28.

[3] Aristotle, A Treatise on Government, trans. William Ellis (London: George Routledge and Sons, 1888), 13.

[4] R. Hillel the Elder, Pirke Avot I.14, trans. Charles Taylor, sacred-texts.com/

[5] Desmond Tutu, quoted in “Mission and Philosophy,” Desmond Tutu: Peace Foundation, www.tutufoundationusa.org/

[6] Thomas Hill Green, Prolegomena to Ethics, ed. A. C. Bradley (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1906), xxix.

[7] Mahatma Gandhi, The Collected Works of M. K. Gandhi (New Delhi, India: Publications Division, 1960), 13:241. “We but mirror the world. . . . If we could change ourselves, the tendencies in the world would also change. As a man changes his own nature, so does the attitude of the world change towards him. This is the divine mystery supreme . . . we do not need to want to see what others do.”

[8] Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks said, “The question that haunts me after the Holocaust, as it does today in this new age of chaos, is ‘Where is man?’” “The Faith of God (Bereishit 5778),” The Office of Rabbi Sacks, 10 October 2017, rabbisacks.org/

[9] Attributed to Bonhoeffer by Eric Metaxas, Bonhoeffer: Pastor, Martyr, Prophet, Spy (Nashville: Thomas Nelson, 2010); though it is claimed to be a hyperbolic metaphor on Twitter, 22 May 2016.

[10] Richard Langworth, “Churchill on Britain and Europe: A Pillar or a Buttress?,” American Spectator, 11 July 2017, https://

[11] Winston Churchill, “The 20th Century—Its Promise and Its Realization” (MIT Mid-Century Convocation, Boston, 31 March 1949), in Winston Churchill: His Complete Speeches, 1897–1963, ed. Robert Rhodes James (New York: Chelsea House, 1974), 7:7807ff.

[12] William Ewart Gladstone, quoted in J. P. Parry, Democracy and Religion: Gladstone and the Liberal Party, 1867–1875 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), 451.

[13] John Wesley to William Wilberforce, 24 February 1791, https://

[14] John Henry Newman, “The Present Position of Catholics in England” (lecture, Birmingham, 1851).

[15] Jacques Maritain, “Rights of Man and Natural Law, The Person and the Common Good, Christianity and Democracy, Man and the State,” chap. 13 of The Collected Works of Jacques Maritain (Notre Dame, IN: University of Notre Dame Press, 1996), Internet edition, https://

[16] Lawrence J. Clipper, ed., The Collected Works of G. K. Chesterton (San Francisco: Ignatius Press), 35:306.

[17] “Declaration on Religious Freedom Dignitatis Humanae on the Right of the Person and of Communities to Social and Civil Freedom in Matters Religious Promulgated by His Holiness Pope Paul VI On December 7, 1965,” The Holy See, www.vatican.va/

[18] “Veritatis Splendor,” The Holy See, w2.vatican.va/

[19] “Encyclical Letter Caritas In Veritate on the Supreme Pontiff Benedict XVI to the Bishops, Priests, and Deacons, Men and Women Religious, the Lay Faithful, and All People of Good Will on Integral Human Development in Charity and Truth,” The Holy See, w2.vatican.va/

[20] Pope Francis, “Address of His Holiness Pope Francis to Representatives of Different Religions” (Clementine Hall, Rome, Thursday, 3 November 2016), w2.vatican.va/

[21] E. M. Forster, Two Cheers for Democracy (London: Penguin, 1965), 83.

[22] “Bobby Kennedy Made This Speech to the Young People of South Africa on Their Day of Affirmation in 1966,” The Conversation, www.theconversation.org/

[23] Reported in “Profile,” Dawn Newspaper, 2 March 2011.