Zwickau Branch, Zwickau District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 501-13.

Zwickau is one of the largest cities in the former kingdom of Saxony, located just nineteen miles southwest of Chemnitz. As World War II approached, the city was home to eighty thousand people and a thriving branch of Latter-day Saints.

| Zwickau Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 12 |

| Priests | 2 |

| Teachers | 4 |

| Deacons | 6 |

| Other Adult Males | 44 |

| Adult Females | 137 |

| Male Children | 3 |

| Female Children | 3 |

| Total | 211 |

The rented rooms in which the Zwickau Branch met throughout the war years were located in the Hinterhaus at Bahnhofstrasse 37. Maria Gangien (born 1926) described the setting:

The main meeting room was just a few steps up from the ground level. We had to go upstairs to the classrooms; there may have been three of them. Sunday School was in the morning and sacrament meeting in the afternoon.[2]

The Gangien family lived on Crimmitzschauerstrasse 5 and walked about twenty minutes to church. “There was no streetcar in our neighborhood,” Maria explained. Her family went home for dinner after Sunday School then returned for sacrament meeting. Relief Society and MIA meetings took place on Wednesday evening, as did choir practice. Regarding the attendance at meetings, Maria recalled about fifty people as an average. Other eyewitnesses estimated the attendance at closer to one hundred.

An excellent history of the branch (and subsequent ward) in Zwickau was produced in 2007 in connection with the centennial celebration. As is typical of Latter-day Saint branch histories, few details about life under Hitler’s government are provided. It is interesting to note that Elder Joseph Fielding Smith presided over a conference in Chemnitz in the summer of 1939, and 170 members of the Zwickau Branch went there to take part in the meeting.[3]

The following events in the branch took place shortly before World War II:

Sunday, February 13, 1938: A conference of the Zwickau Branch Primary Association was held. It was attended by one hundred and five persons.[4]

Tuesday, February 22, 1938: The Zwickau Branch Mutual Improvement Association presented a musical program, followed by an illustrated lecture. One hundred and thirty-two persons were in attendance.[5]

Sunday, March 13, 1938: A program commemorating the organization of the Relief Society was given in the Zwickau Branch. It was attended by one hundred and twenty-six persons.[6]

Friday, March 3, 1939: A social was held in the Meerane Branch, Zwickau District. It was attended by members and friends of the Zwickau, Werdau, and Planitz branches, The sum of RM 10.00 was collected for the Meerane Branch Welfare Association.[7]

Unfortunately, not all news reported to the mission office in Berlin was positive. Under the date Thursday, March 31, 1938, it was reported that the police had forbidden the branch Mutual Improvement Association to hold an Easter celebration. There was no justification provided.[8]

The first Hinterhaus at Bahnhofstrasse 37 was the home of the Zwickau Branch. The entrance is at the far right (see photograph below). (Zwickau Branch History)

The first Hinterhaus at Bahnhofstrasse 37 was the home of the Zwickau Branch. The entrance is at the far right (see photograph below). (Zwickau Branch History)

“I was in the Reichsarbeitsdienst when the war started,” recalled Erika Fassmann (born 1920). To Erika, being a teenager in Hitler’s Germany was not all bad. She loved associating with other girls in the League of German Maidens. “But my father knew that [Hitler] was not a righteous man, and he always told me that.”[9] However, district president Walter Fassmann and his wife seldom expressed their critical opinions about National Socialism, Hitler, or the war. Daughter Helga Fassmann (born 1930) recalled that her sister, Erika, and her brother, Walter (born 1922), were enthusiastic members of the Hitler Youth at the time; it was feared that they would unwittingly relay to leaders negative political comments made at home, which could have had serious consequences.[10]

A Priesthood gathering in Zwickau. Apostle John A. Widtsoe was the special guest on this 1937 occasion. He is seen in the front row, third from left. The banner reads, “The glory of God Is intelligence.” (M. Gangien Mannek)

A Priesthood gathering in Zwickau. Apostle John A. Widtsoe was the special guest on this 1937 occasion. He is seen in the front row, third from left. The banner reads, “The glory of God Is intelligence.” (M. Gangien Mannek)

The Zwickau Branch made a substantial contribution to the German war effort from the very beginning. By September 20, 1939 (the successful end of the German campaign against Poland), no fewer than nineteen brethren had been drafted. Evening meetings were set for earlier times in response to regulations regarding blackouts.[11]

One of those young men drafted in the first month of the war was Heinz Gangien (born 1915), Maria’s brother. By then, he had actually received a letter from Mission President Alfred C. Rees and was preparing to leave on a mission. With Germany at war, the mission call could not be honored. Heinz was drafted by the Wehrmacht right away and served for more than five years.

Just after the war started, Maria Gangien finished public school and applied for admission to a business college. Because her father had not allowed her to participate in the Hitler Youth organization, her entry into the college was almost blocked by the party. Fortunately, her scholastic record was so strong that she could not be denied admission.

Daily life for teenagers in Zwickau was not all work and suffering during the war. According to Maria Gangien, the youth of the Zwickau Branch continued to enjoy get-togethers on Saturdays when they went to the woods and played ball. “We had a very good youth group in our Church. We always tried to stick together and do fun things. On New Year’s Eve we celebrated in the [branch]. We had nice programs.” Helga Fassmann later recalled that there were no disturbances in the normal church routine. Until 1945, “Everything was fine.”

Air-raid warnings were commonplace in Germany as early as 1940. In Zwickau (where peace prevailed for the first few years of the war), the branch leadership organized pairs of members to watch out for the meeting rooms. They were to go there as soon as possible after an attack, in case there was a fire to put out. Young Walter Fassmann recalled going to Bahnhofstrasse 37 in the middle of the night. Even young women were assigned to this service and were safe in doing so, despite the blackout conditions.[12]

The youth of the Zwickau Branch took a trip to Meerane in April 1939. (W. Fassmann)

The youth of the Zwickau Branch took a trip to Meerane in April 1939. (W. Fassmann)

In 1940, Erika Fassmann was called to be a full-time missionary and to serve in the office of the East German Mission in Berlin. For the next five years, she traveled all over the mission to participate in district conferences and conduct training sessions for the auxiliary programs of the Church.

The official Zwickau Branch history recounts a very sad story that unfolded in 1941:

Brother Ewald Beckert was arrested in 1941 because he had smuggled bread to Russian POWs. He was taken into custody and placed in the Zwickau jail. From his cell, he wrote to his family, told them that he was fine and that he hoped to be released the next day. However, his family received notification the next day that he had taken his own life. [When they saw the body ] . . . they found that his wrists had been slit, but also that there was an injury to his neck.[13]

As a teenager in a prosperous Germany, Walter Fassmann had “shared in the pride of the German people” as Hitler achieved bloodless conquests in the Rhineland, Austria, Czechoslovakia, and other territories bordering Germany. “As I grew older, my enthusiasm for National Socialism waned.” Nevertheless, he had a good experience serving for seven months in the Reichsarbeitsdienst in Czechoslovakia.

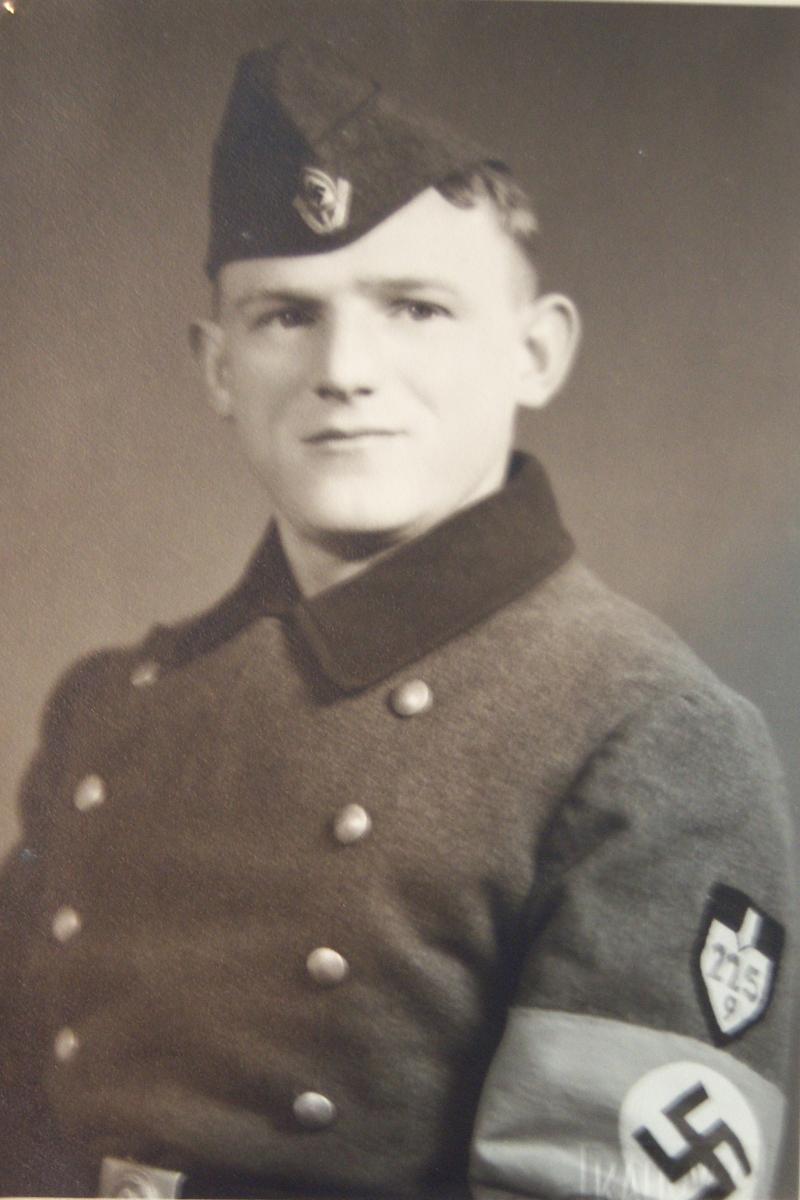

Young Walter Fassmann in the uniform of the Reichsarbeitsdienst (W. Fassmann)

Young Walter Fassmann in the uniform of the Reichsarbeitsdienst (W. Fassmann)

Walter Fassmann returned from his service in the Reichsarbeitsdienst and in less than one week was drafted into the military. Assigned to the German navy, he began a long journey that took him first to Stralsund, Rügen Island, then to Sweden and Norway. He ended up at a coastal artillery battery near Haugesund, Norway, and received additional training there. Next, he was assigned to a battery on the island of Kvitso, where he lived under very isolated conditions for six months. While there, he became enthralled with the sea and with nature in general. He saw no military action during that time.

Some of the events of the year 1941 were described in a second (unpublished) history of the Zwickau Branch:

On September 5, two converts were baptized, along with six children (of member families) who had reached the age of eight years. Fourteen sisters married nonmembers during the year and most of them became inactive. Some also married soldiers at the front. Some elderly members passed away, having been faithful to the end. The population of the branch continued to decrease.

Inge Beckert (born 1927) finished school at the age of fourteen and was immediately called upon to do her Pflichtjahr on a farm in Marienthal (about ninety minutes walking time from Zwickau). She later described the situation: “I had to work hard. We got up at 5:00 a.m. and worked all day long. They were good people on that farm, but I hated the farm work. I only got one Sunday a month free.”[14]

On March 17, 1942, Heinz Gangien married Maria Graf, a recent convert to the Church. The ceremony took place in the office of the civil registrar, after which another ceremony was held at church. The ensuing celebration was of necessity quite simple; as Heinz’s sister, Maria Gangien, recalled: “We just had a simple meal at home with close family members.”

The interior of the branch meeting rooms at Bahnhofstrasse 37 (M. Gangien Mannek)

The interior of the branch meeting rooms at Bahnhofstrasse 37 (M. Gangien Mannek)

Despite the privations of wartime, branches in Germany tried to observe special events as they believed was done among Saints around the world. One such event was the centennial of the founding of the Relief Society that was celebrated throughout Germany in 1942. In Zwickau, the program was attended by 190 persons.[15]

Unfortunately, as the war continued, the rich variety of branch activities began to wane. As of 1943, only two meetings were still being held in Zwickau: Sunday School at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting at 7:00 p.m.[16] Eight persons were baptized on September 2 that year. Later that month, a musical talent night was held, and voluntary donations collected on that occasion were used to purchase a new organ.[17]

For a land-based navy man like Walter Fassmann, life on an island was idyllic for a time, but he eventually longed for something more exciting. In June 1942, he volunteered for training as an artillery mechanic and was transferred to the town of Wesel on the Rhine River. In October, he was sent to Kiel, a Baltic seaport. On the way, he found the opportunity to visit his sister, Erika, in the mission office in Berlin. While in Kiel, Walter hoped to attend church, but was unsuccessful, as he described:

After finding out the address of an LDS branch in Kiel, I started out one Sunday to go to church. I had to walk a long time before I reached the place, only to find a sign on the door that read “Closed for remodeling.” That was the only time I had a chance to go to church as a soldier.

From Kiel, Walter moved on to Swinemünde, Germany,and finally to Russia, just west of Leningrad. He was never in combat during that assignment and very much enjoyed being there, where he interacted with Russian civilians. During his travels in August 1943, Walter had a dream that he described years later:

Alone in a train compartment, I had fallen asleep in the middle of the day. I can no longer recall the details, but I was aware that [my brother] Heinz had lost his life. I could trace back the day and the hour of that dream and found that it coincided with the day and hour of his death.

Heinz Fassmann had been killed in battle in the Soviet Union, and Walter’s dream was confirmed when he spoke with Erika again in the mission office in Berlin. She had received the news from their family in Zwickau.

Following a second training course in Wesel on the Rhine, Walter was sent through northeast Germany to Greece, traveling through his hometown and Austria on the way. After seeing Athens, he moved on to the harbor in Piraus, where he was assigned to service large weapons aboard transport vessels. He never left the mainland. In September 1944, the German forces in Greece began to retreat. On the way, Walter had time to pray and to reflect upon his good fortune: “My whole career in the navy passed before my eyes and it became clear to me that my Heavenly Father had always protected and guarded me so that I never had been directly involved in the battles of the war.” However, as he continued to pray a different feeling came over him:

While I was pouring out my heart in a prayer of gratitude and thanksgiving, I suddenly saw gruesome, grotesque faces approaching me. They looked as if they were made of thick strands of wool. After coming directly in front of me they vanished into thin air. But more and more multitudes of them appeared from nowhere, rushing toward me. I was wide awake. Opening or closing my eyes did not change anything in the gruesome apparition. These ugly, terrifying faces were grinning and looking at me as if to say that from now on the wind would blow from a different direction.

Maria Gangien and Inge Beckert at the entry to the meeting rooms at Bahnhofstrasse 37 in 1942. The word Luftschutzraum above the door means “public air-raid shelter.” (M. Gangien Mannek)

Maria Gangien and Inge Beckert at the entry to the meeting rooms at Bahnhofstrasse 37 in 1942. The word Luftschutzraum above the door means “public air-raid shelter.” (M. Gangien Mannek)

The move north from Greece took Walter to Yugoslavia, where progress was slow due to the gradual breakdown of the German military system. Transportation was seriously hampered by the actions of local partisans, and supplies and food were difficult to come by. By Christmas, Walter’s physical condition was pitiful, as he later wrote:

I really must have been a sight! Just imagine: My disheveled beard was crusted with ice. Over my head I had pulled a lady’s stocking to keep my ears warm. On the top of my head I wore a filthy field service cap. For a shawl worn over my gray leather jacket, I had another lady’s stocking. . . . For gloves I had two socks. On one foot I wore a boot and on the other a shoe. All my possessions, consisting of a few toilet articles and a few pieces of underwear, were in a haversack. I carried my rifle upside down, like a stick over my shoulder.

In distant Berlin in 1944, Walter’s sister, Erika Fassmann, was in her fifth year as a missionary. That year, she married Rudi Müller, a member of the Danzig Branch, whom she had known for more than two years. She explained her formal deportment in relation to Rudi in these words: “I was a missionary and was not supposed to have anything to do with men. He called me ‘Sister Fassmann’ and asked me in a letter to marry him. I said ‘yes’ in a letter.” Later, she traveled with her mother to Danzig to meet the Müller family. The marriage took place in the civil registry in Zwickau on the morning of October 26, 1944, followed by a ceremony in the church that afternoon. Erika’s story continued:

Brother [Ernst] Ebisch prayed and promised that we would someday marry in the temple. We thought this would be impossible in our lifetime. Such a wonderful promise. My cousin carried the train of my dress and we had flower girls, too. We had a wedding dinner in our apartment. . . . My mother had connections with a farmer and got enough food to feed the relatives and a few people from the branch. It was a great meal.[18]

Newlyweds Erika and Rudi spent three days in her parents’ apartment, and then he took the train back to his post with the German navy and she returned to the mission office in Berlin, where she served until March 1945. She did not see him again for more than four years. She returned to service as a missionary in early 1948 and was released when Rudi returned later that year from his term as a prisoner of war in Yugoslavia.

When the year 1945 arrived, few people in the Zwickau Branch believed that Germany could still win the war. Under this cloud of discouragement, the priesthood holders in the branch met on New Year’s Day for a testimony meeting. They were able to strengthen each other and to gain renewed dedication to carry out their duties.

Walter Fassmann’s situation had improved somewhat after Christmas 1944, when he found himself on duty in the port city of Trieste, Italy. The previous three months had represented what he later called “the greatest hardships of my entire life.” Cleaned up and fed, he was actually allowed a furlough and went home to Zwickau for two weeks in January 1945. By the time he returned to Trieste, he was a naval mechanic petty officer with duty in a very safe area.

Maria Gangien graduated from business college in 1943 at the age of seventeen and was called right away to serve her Pflichtjahr on a farm. She returned in time to experience the Allied attacks on the city from the air. When the bombs began to fall on Zwickau, the Gangien family sought shelter in their own basement. There was no public air-raid shelter close by. “Our basement would not have been sufficient protection if a bomb hit our house, but it was the only shelter we had. Our house was not destroyed in the war,” Maria explained.

Maria Gangien spent six months in government service on a farm after graduating from business college. (M. Gangien Mannek)

Maria Gangien spent six months in government service on a farm after graduating from business college. (M. Gangien Mannek)

Inge Beckert recalled two specific occasions when Zwickau was attacked from the sky—September 11, 1944, and March 19, 1945. On the first occasion, her sister Marianne was giving birth in the local hospital, and the second time, all of the windows were broken in the neighborhood where her sister, Hanne, lived. Fortunately, the Church rooms were not damaged in either attack.

Elenore Gangien (born 1938) was just a little girl when Allied bombers dropped their loads on Zwickau. She was not old enough to understand why nations were at war, but she recalled being scared:

The only fear I would say we had was when we heard the sirens, and it was usually in the middle of the night, and everything had to be closed off, and as a child you got carried out. . . . Your mother dressed you and took you down to the cellar where all the neighbors met. You’re half asleep and you sit there and hope the bombs don’t fall on your house.[19]

After one air raid, Grandpa Gangien came by with a bus and offered to take the family on a little ride. What they saw impressed little Elenore and she clearly recalled it years later: “He showed us the newly bombed houses [in a suburb]. It was shocking to me because there was still smoke coming [out] and these were all the single homes out there. It was just a village of single homes, nice homes. That gave me as a child a strange feeling.”

In March 1945, Paul Langheinrich, second counselor in the leadership of the East German Mission, granted Erika Fassmann Müller permission to go home to Zwickau. She planned to attend the festivities associated with the silver wedding anniversary of her parents, then to return directly to Berlin. She experienced an adventuresome railroad journey to south Zwickau, lasting several days rather than the usual several hours. Along the way, she found herself on a train loaded with soldiers. When airplanes attacked the train, everybody scrambled out and sought hiding places near the tracks. Always the missionary, Erika saw a fine opportunity:

I preached the gospel to those soldiers, but they didn’t want to listen. One was a lieutenant who was trembling with fear. I asked if I could pray. They said yes, so I prayed loudly enough to be heard. Not one bomb hit the train. Then we got back into the train, and I continued to preach the gospel, and this time nobody protested.

Sister Müller arrived in Zwickau in time to help celebrate the silver wedding anniversary of her parents on March 20. By the time she was ready to return to Berlin a few days later, the Soviets had surrounded the capital, and travel to that city was impossible.

Maria Gangien remembered taking this photograph of her sister, Elionor, just as American bombers entered the air space over Zwickau. (M. Gangien Mannek)

Maria Gangien remembered taking this photograph of her sister, Elionor, just as American bombers entered the air space over Zwickau. (M. Gangien Mannek)

On one occasion, Maria Gangien was at work in an office downtown when the air-raid sirens went off. Her boss instructed her to go home, so she left. Arriving at home with her sister, they stopped in front of the house to take a few pictures. The sirens were wailing, and the roar of the approaching bombers could be heard already, but the girls took a moment to take photographs. “We were crazy and did it just for fun. It was an adventure,” she explained. Fortunately for the Gangiens and the other residents of Zwickau, the great majority of air-raid alarms were false alarms as the airplanes passed by the city on their way to other targets.

Maria Gangien’s brother, Heinz, was reported missing in action while fighting the invading Soviets in March 1945. Maria recalled her parents’ reaction to the news of Heinz’s disappearance:

My father kept saying “My only son! My only son!” [Heinz] was there [in the Wehrmacht] from 1939 to 1945, [nearly] six years. It was very sad. . . . We don’t know how he died. We don’t know where. . . . The last letter we got from him said that he was close to St. Petersburg [Russia]. Three letters were returned with the comment “killed in battle.”

Young Elenore Gangien remembered the sorrow in her home when they received the news. She also recalled her grandmother saying, “Well, they can’t find him, so he’s still alive.” She was not prepared to relinquish her hope. The custom in Germany at the time was still to wear black clothing for a year of mourning. According to Maria Gangien, they did not observe that custom for the entire year because the war had ended and conditions had changed.

On April 17, 1945, American artillery fired upon the city of Zwickau for several hours. Airplanes overhead threatened more destruction when (according to several eyewitnesses) a few brave citizens climbed the tower of the Marienkirche downtown and hoisted a white flag. An act that could have resulted in execution for treason apparently spared the city additional destruction and suffering.

During the American artillery barrage, members of the Zwickau Branch were gathered in the home of the Ficke family, where district president Walter Fassmann Sr. led a prayer circle. According to his daughter, Erika Fassmann Müller, “he prayed that the Lord might protect us and our city. . . . We heard the planes approaching the city, but not one bomb fell.” Later, she wrote in her diary, “Zwickau surrendered. Our city has survived. We should build an altar to the Lord.”[20]

The American army entered the city of Zwickau just days before Germany surrendered and the war came to an end. According to Maria Gangien, “We were so happy to see [the Americans]. We came out of church and saw white flags flying. It was very quiet.”

“We lived on the second floor of the [apartment house],” recalled Elenore Gangien. “As a child, you would look out the window and wave and they were happy people—those Americans. They’d toss their candy and . . . it was really fun. Those were two glorious weeks.”

In accordance with an agreement among the Allied nations, the Americans vacated Zwickau and all of Saxony on July 1, and the Soviets moved in. Undisciplined Russian soldiers immediately set out in search of women to assault, as Maria Gangien recalled:

My father was a husky man. When he opened the door, [the Russian soldiers] asked, “Frau hier? Frau hier?” There were four of us girls, and my father said “No!” We were hiding under the beds. Then they left. . . . For some reason we were protected. We had extra help. . . . It was a very dangerous situation.

Helga Fassmann recalled how the conquerors moved into her family’s apartment:

We couldn’t lock the door and so they could get in anytime they wanted. But when they lived in our house, the only thing we actually lost were my mother’s nice drinking glasses. Sometimes they would drink their vodka and throw the glasses out of the window. One day they asked me to drink with them, and I said to them, “I don’t drink that.” One day I was angry enough that I threw their vodka out the window, and boy, I thought they were going to kill me. . . . But they were usually friendly with me and gave me lots of food.

On May 1, 1945, Walter Fassmann’s position in Italy was attacked by Yugoslav partisans. The German forces retreated into the city of Trieste, and it was there that Walter Fassmann was taken prisoner just days before the war ended. He was soon to understand the meaning of the grotesque faces in the dream he had years before. Life as a POW in Yugoslavia was torture at best. For nearly four years, he would suffer, work, and survive in that country, while thousands of his comrades perished.

Soon after his capture, Walter ran into Rudi Müller of the Danzig Branch, who had married Walter’s sister, Erika. The two POWs were able to stay together for several months. While marching through the Yugoslavian countryside for weeks, Walter discovered that he was holding up better than most of his comrades. He attributed his ability to “run and not be weary and walk and not faint” to his adherence to the Word of Wisdom.

During his years of incarceration, Walter contracted several life-threatening illnesses (including typhus) and was incoherent for days at a time. With no proper medical facilities or personnel at hand, he easily could have died more than once. When healthy enough to work, he spent his time building houses, doing farm work, and repairing army vehicles. “None of these chores was too hard for me,” he wrote.

On Easter Sunday 1947, Walter had a moving experience. While he languished inside the POW camp, a girl of perhaps thirteen came and gave him a colored Easter egg, reaching her hand through the fence to him. Then she quickly ran away.

It was quite risky for her to come so close to the fence. I cannot remember into how many pieces we [prisoners] divided the egg. Nobody got much. But a gift under these circumstances was something special. . . . The effect of this gift was profound. From that moment on, I was no longer hungry all the time.

Living conditions for German POWs such as Walter Fassmann and Rudi Müller improved markedly in 1947 and 1948. They were allowed to send and receive mail, to wander about town after their working day, and to purchase goods in local stores with their meager wages. They were fed well, and their physical and emotional health improved substantially. In January 1949, Walter was released to return to Germany (Rudi had left a few months earlier). Looking back on the end of his POW term and his experiences in uniform in general, Walter wrote:

Thus, the most difficult period of my life had come to an end. I had been away from home almost exactly eight years. Several months in the Reichsarbeitsdienst, three years and eight months in the Germany navy, and three years and nine months as a prisoner of war in Yugoslavia. Many people would consider time spent under these conditions as time wasted. I do not share this feeling. I value this span of my life because during this time I had experiences I could have had no other way. These experiences have enriched my life, strengthened my character, strengthened my testimony of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and brought me closer to God. I have never had feelings of hate toward the so-called enemy, even when I was mistreated by them, and I never needed to point a gun toward another human being.[21]

Surviving priesthood holders of the Zwickau Branch (W. Kindt)

Surviving priesthood holders of the Zwickau Branch (W. Kindt)

Looking back on her experiences in Zwickau during the war years, Maria Gangien made this comment: “I am grateful for the members in Zwickau because we really helped each other in faith.”

In Memoriam

The following members of the Zwickau Branch did not survive World War II:

Ernst Hermann Ackermann b. Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 7 Jun 1871; son of Karl Gottlieb and Wilhelmine Liewald; bp. 15 Jul 1909; m. Verronica Kohlert; d. old age 12 Dec 1944 (FHL Microfilm 25708, 1930 Census)

Max Ewald Beckert b. Weissbach, Zwickau, Sachsen 7 Apr 1889; son of Friedrich Wilhelm Beckert and Lina Ida Kunz; bp. 18 Mar 1908; ord. deacon; m. Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 4 Jul 1914, Marie Elisabeth Schmitzler; 4 or 5 children; d. questionable circumstances Zwickau Jail Zwickau 22 Oct 1941 (Zwickau Branch History; FHL Microfilm 25721, 1930 Census; IGI; AF)

Ernst Louis Ebisch b. Stein, Hartenstein, Zwickau, Sachsen 29 Jul 1865; son of Louis Friedrich Ebisch and Ernestine Wilhelmine Bochmann; bp. 4 Apr 1922; m. Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 23 Jun 1891, Aurora Lina Reich; 7 children; k. in air raid Zwickau 19 Mar 1945 (E. Fassmann Mueller; Zwickau Branch History; IGI)

Heinz Fassmann b. Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 20 Nov 1924; son of Walther Fassmann and Anna Clara Förster; bp. 4 or 7 Oct 1934; d. wounds Sokolowo, Russia 22 Aug 1943 (E. Fassmann Mueller; IGI; AF; PRF)

Lina Fassmann b. Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 19 Dec 1890 or 1891; dau. of Louis Franz Fassmann and Margarethe Raithel; bp. 4 Dec 1909; m. Hamburg 28 Oct 1919, Wilhelm Ernst Louis Mauber; 2 children; k. air raid Hamburg 1 Jul 1943 (H. Fassmann; IGI; AF)

Louis Franz Fassmann b. Strassberg, Zwickau, Sachsen 6 May 1861 or 1863; son of Johann Christian Fassmann and Antonie Mathilde Lautenschlaeger; bp. 3 May 1909; m. Plauen, Zwickau, Sachsen 20 Apr 1889, Margarethe Raithel; 10 children; d. pneumonia Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 13 Sep 1941 (CHL Microfilm LR 10378 11, Zwickau Branch General Minutes; IGI; AF)

Hedwig Carola Fischer b. Oberlochmühle, Chemnitz, Sachsen 18 Jun 1889; dau. of Otto Heinrich Fischer and Albine Sidonie Schmerler; m. 20 Oct 1912, Paul Georg Rost; 6 children; d. by abdominal cancer 20 Jun 1942 (FHL Microfilm 271407, 1930/

Rolf Wolfgang Guenther b. Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 16 Sep 1919; son of Ernst Erich Guenther and Edith Lea Waldbrunn; d. in WWII (CHL CR 375 8 #2460, 562–63)

Heinz Kurt Günter Walter Gangin b. Kötitz, Dresden, Sachsen 11 Oct 1914; son Kurt Julius Walter Gangin and Ella Franziska Tierlich; bp. 9 Aug 1924; ord. teacher; ord. elder Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 1939; m. Zwickau 17 Mar 1942, Maria Graf; 1 child; k. in battle Eastern Front Feb or Mar 1945 (Gangien-Mannig; AF; IGI; FHL Microfilm 25771, 1935 Census)

Paul Rudolf Hermann d. suicide Crossen 17 Aug 1941 (CHL Microfilm LR 10378 11, Zwickau Branch General Minutes)

Konrad Meixner b. Vorra, Mittelfranken, Bayern 17 Dec 1864; son of Johann Georg Meixner and Christine Sperber; bp. 8 May 1925; m. Hohenleuben, Reuss-jüngere Linie 4 Jul 1886, Rosa Antonie Gerstner; 5 children; d. Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 8 Sep 1940 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 3, 19 Jan 1941, 12; IGI)

Frieda Helene Mothes b. Pölbitz, Zwickau, Sachsen 26 May 1878; dau. of Otto Mothes and Helene Marie Wagner; bp. 18 May 1920; m. —— Weichelt (div.); 1 child; d. cerebral embolism 31 Oct 1939 (CHL Microfilm LR 10378 11, Zwickau Branch General Minutes; IGI; FHL Microfilm 245296, 1930/

Antonie Rosa Notzold b. Oberhohoudry [?], Germany 1 Apr 1904; m. —— Markert; k. in air raid 1945 (FHL Microfilm 245226, 1935 Census; Zwickau Branch History)

Margarethe Raithel b. Streitau, Oberfranken, Bayern 15 Apr 1866; dau. of Franz Julius Jahnsmueller and Barbara Raithel; bp. 3 May 1909; m. Plauen, Zwickau, Sachsen 20 Apr 1889, Louis Franz Fassmann; d. Zwickau, Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 2 Apr 1943 (IGI; AF; CHL Microfilm LR 10378 11, Zwickau Branch General Minutes)

Horst Erhard Schaller b. Zwickau, Zwickau, Sachsen 22 Mar 1927; son of Edmund Alfred Schaller and Helene Gertrud Boettcher; bp. 13 Jun 1935; k. in battle Eastern front 19 Apr 1945; bur. Schwedt/

Auguste Jenny Waechtler b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 5 Aug 1888; dau. of Max Friedrich Waechtler and Emilie Auguste Wunderlich; bp. 29 Nov 1907; m. Kurt Bendel; d. 28 Nov 1943 (CHL Microfilm LR 10378 11, Zwickau Branch General Minutes; IGI)

Selinna Werdauen d. heart attack, 24 Nov 1944 (CHL Microfilm LR 10378 11, Zwickau Branch General Minutes)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Maria Gangien Mannek, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, July 6, 2007.

[3] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Geschichte der Gemeinde Zwickau, 1907–2007, 25; private collection.

[4] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 11, East German Mission History.

[5] Ibid., no. 12.

[6] Ibid., no. 14.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Erika Fassmann Mueller, interview by the author in German, Salt Lake City, February 3, 2006; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[10] Helga Fassmann Kupitz, interview by Michael Corley, West Jordan, Utah, March 7, 2008.

[11] “Die Geschichte der Gemeinde Zwickau in Kurzfassung” (unpublished history); private collection

[12] Walter K. Fassmann, autobiography, 41.

[13] Geschichte, 25.

[14] Ingeborg Beckert Fassmann, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, February 1, 2008; unless otherwise noted, transcript or audio version of the interview in the author’s collection.

[15] Geschichte, 26.

[16] Ibid.

[17] Ibid.

[18] In April 1945, Ernst Ebisch was killed in an air raid in Zwickau.

[19] Elenore Gangien Vielstich, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, July 12, 2007.

[20] Sister Müller lost her first three diaries when the office of the East German Mission in Berlin was destroyed in 1943.

[21] Seven months after Walter arrived at home in Zwickau, he was called upon to baptize an eight-year-old boy named Dieter Friedrich Uchtdorf.