Tilsit Branch, Königsberg District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 320-34.

Internationally famous for its distinctive cheese, the city of Tilsit was located in the northeast corner of East Prussia, approximately forty-two miles from the capital city of Königsberg. The population of the city in 1939 was 59,000.

| Tilsit Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 2 |

| Priests | 3 |

| Teachers | 2 |

| Deacons | 6 |

| Other Adult Males | 22 |

| Adult Females | 52 |

| Male Children | 1 |

| Female Children | 5 |

| Total | 93 |

In early 1939, the Tilsit Branch was meeting in rented rooms at Schlageterstrasse 54, on the main floor. Waltraut Naujoks (born 1921) described the meeting rooms as follows:

We entered the house from the street side and went up some stairs, which led to a room before the actual room for our meetings. Then, there was a small room that was used as a cloakroom. There was also another small room for the Primary and the Young Women (called Beehives). The large meeting room was used for Sunday School and sacrament meeting. [2]

Eva Schulzke (born 1930) provided the following detail from her memories:

It was two rooms, one in the front and the other room was [for] little classes. And there was terrible cold in the wintertime; we didn’t have any heat and the toilet was frozen. There were no pictures on the walls and we didn’t have a pulpit—just a table. We didn’t have a pump organ or anything—we just sang from our books.[3]

Helga Meiszus (born 1920) remembered a less attractive characteristic of the rooms at Schlageterstrasse:

It used to be a restaurant and a beer hall. The smell of beer doesn’t go away overnight and then of course [there was] a lot of smoke in the walls and curtains and whatever. . . . Before we started our meetings, we had to open all the windows first because it was quite a smell.[4]

There were few decorations, but Helga also remembered having fresh flowers in the rooms on a regular basis.

The branch observed the typical meeting schedule, with Sunday School in the morning and sacrament meeting in the evening. For many families, it was very inconvenient to take little children back to church in the evening. Waltraut Naujoks remembered walking for one hour each way from their home outside of town to church. “In the evenings, my mother and father took bikes to ride to Church so that they could attend sacrament meeting.”

Arthur Naujoks had fond memories of the social life in the Tilsit Branch:

“Without question, the social event of the year was a gala New Year’s Eve party, held at the meetinghouse, complete with refreshments and a stunning array of cakes and sweets.”[5]

The Tilsit Branch Sunday School in about 1935 (H. Meiszus Birth Meyer)

The missionaries from America were evacuated from Germany on August 25, 1939. The move came so quickly that most of the local Saints did not have the opportunity to send them off. Arthur Naujoks was fortunate to be there as they departed:

When the news came calling the missionaries to Copenhagen [Denmark], I helped Elder Oscar Sither load his bags onto a handcart and then hauled them to the train station. . . . I was sad to see the elders go but was relieved that they would get out safely before any serious trouble began.[6]

A New Year’s celebration in the Tilsit Branch (E. Schulzke Bode)

A New Year’s celebration in the Tilsit Branch (E. Schulzke Bode)

Eva Schulzke was baptized in the Memel River when she was nine years old. When she turned ten, she and her classmates were inducted into the Hitler Youth. She missed a few meetings early on due to church attendance and was told that if she continued to be absent, the police would come for her. Fortunately, she found a way to avoid conflict, but the sports and the craft activities never particularly interested her.

“I was part of the Hitler Youth although I did not support their methods,” recalled Bruno Stroganoff (born 1923). “In the Hitler Youth, I got the chance to participate in training for firefighters. I also learned how to ride a horse. This training took place outside of Königsberg.”[7]

The Augat family lived in the small rural community of Rautengrund, about ten miles from Tilsit. Because of the inconvenience of travel from Rautengrund to Tilsit, and because her husband was not a member of the Church, Berta Augat usually went to the meetings by herself. According to her daughter, Ursula (born 1935), and her son, Heinz (born 1936), their mother took the horse-drawn wagon to the town of Unter Eisseln on the Memel River. From there, she took the boat downriver to the city of Tilsit and then walked through town to church. Ursula and Heinz did not recall going to Tilsit to church with their mother, but they clearly remembered having Sunday School with her in their home, where she taught them the gospel and sang the hymns of Zion with them.

While at work in a pharmacy on Friday, September 1, 1939, Helga Meiszus heard the announcement that Germany had invaded Poland:

I was there in the store, and it was not even noontime and the people came and bought everything under the sun. They bought everything, whatever they could. Whatever they needed, and the store was empty. It was not even noontime. . . . It was not long then the news came that the first of the soldiers got killed. So it was a gloomy day. It seems like the streets were . . . empty. It was like a numbness. Everybody was shocked.

Helga’s father, a sergeant in the Wehrmacht, was immediately activated and sent to Poland. The family at home had time to consider what they had heard the previous year from LDS Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith, when he spoke at a district conference in Königsberg. Helga recalled his message:

The year before [1938], we had a special meeting in Königsberg, the capital of East Prussia . . . with then Elder Joseph Fielding Smith. He was there, and I will never forget, he gave a talk—of course it was in English and then translated. He encouraged all the members to have a storage of coal to make fire. Wood and coal and special briquettes. He encouraged us to fill our basements with it and to have blankets. It seems like he really prepared us for this time.

Ursula Lessing (born 1927) also lived with her family far from the Tilsit Branch. Her parents, Willi and Emma Lessing, lived in a small house in Kallwehlen, a farming community on the north side of the Memel River in the Memelland. They were just a mile from the Russian border in what is now Lithuania, probably farther east than any other LDS family in Germany. The Lessings rarely made the fifty-mile trip to Tilsit to church; their only real connection came through the parents of Emma Lessing, Carl Otto and Ida Hübner.[8]

Ursula Lessing in the uniform of a BDM girl in about 1941 (U. Lessing Mudrow)

Ursula Lessing in the uniform of a BDM girl in about 1941 (U. Lessing Mudrow)

The Hübners operated a riverboat in the region. They coursed the Memel River and several other rivers and canals in the Memelland and East Prussia. It was an odd lifestyle, but the Hübners were happy members of the Church and attended meetings whenever possible.

Berta Augat’s husband, Fritz, was not a member of the Church. He was drafted in the first year of the war. Leaving his wife and little children, he was destined to serve for the remainder of the war and was allowed to come home on leave only a few times. He was assigned to an engineering corps and spent his time building roads and bridges.[9]

Tilsit Saints enjoyed a social occasion in the home of Branch President Otto Schulzke in 1943.

Tilsit Saints enjoyed a social occasion in the home of Branch President Otto Schulzke in 1943.

In about 1942, some soldiers walked into the church rooms where Helga Meiszus was conducting a Primary meeting. They informed her that they needed to confiscate the rooms for army storage purposes. She insisted that the Church needed the rooms and was actually successful in defending some of the property. The soldiers eventually used only the larger room at the back, leaving the front rooms for regular meetings.

Helga Meiszus continued to work in Tilsit and lived with her grandparents. On February 11 , 1942, she married Gerhard Birth of the Schneidemühl Branch. He was a fine young man, and the wedding was a joyous occasion, but their life together was brief. A few days after the wedding, Gerhard returned to the front and was killed on April 1—less than two months later. The report of Gerhard’s death reached Helga on Hitler’s Birthday (celebrated all over Germany each year on April 20). That anniversary became one of very bad luck for Helga Meiszus Birth. On April 20, 1943, she was sitting in a bomb shelter when a bomb landed just a few feet away. She explained the circumstances:

I was wounded by shrapnel in my neck. I had my fur coat on and the fur coat had a big lining, a heavy lining, and one piece [of shrapnel], instead of going into my intestines, it didn’t go in because of the lining of my fur coat. . . . In that moment I thought, I’m going to die and I will see my husband. I twisted around and then when you are in a situation like that it is hard to believe how fast your thoughts are going. I saw my whole life like a film rolling [by] and all my thoughts and I knew my family will be sad.

Fortunately, Helga was lucid enough to leave the air-raid shelter and walk to the hospital, where a physician pronounced, “[You are] very lucky. You could have been paralyzed.”

The Lessing family moved to Szillen in East Prussia (about ten miles south of Tilsit) during the war. Willi Lessing had been inducted into the rural police and stationed there. About that time, the Hübners gave up their life on the riverboat and went to live on the farm in Kallwehlen. Both families were isolated from the Church.

Life in rural Rautengrund during the war was a pleasant experience for the Augat children, but they missed their father. In the last year of the war, the city of Tilsit came under attack by Soviet airplanes. The Augat children vividly recalled seeing the “Christmas trees” (illumination flares) over the city from their distant vantage point. They were only eight and nine years old at the time, but they were sufficiently aware of the events to be very frightened of the pending invasion. They saw the red lights on the horizon when Tilsit burned, observed the last German defenders digging defensive trenches and retreating, and watched as German and Soviet fighter planes dueled in the sky. Eventually, they heard the Red Army artillery in the distance. According to Ursula, “It was horrible, and I was very scared, and I didn’t even understand the full extent of what was happening.”

The youth of the Tilsit Branch clown around on a wintry Sunday afternoon in 1943. Four of them did not survive the war. (H. Meiszus Birth Meyer)

The youth of the Tilsit Branch clown around on a wintry Sunday afternoon in 1943. Four of them did not survive the war. (H. Meiszus Birth Meyer)

When Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, Arthur Naujoks was a witness to some of the first events of the campaign because the Russian border was barely twenty miles to the east of Tilsit. As he later wrote, “In a matter of hours, thousands of Soviet POWs were marching through Tilsit. I was headed to my Sunday School class, barely able to hear the artillery moving away into Belarus.”[10]

Arthur was drafted a few months later and in 1942 took part in the offensive that was designed to take the German army into Moscow. By January 4, 1943, he was with his unit in what was possibly the worst place on earth for German soldiers at that time: just west of the city of Stalingrad. He had just been informed by his commanding officer that the Soviets had surrounded their position and that he hoped they could break out and head west to rejoin German units. Then the commander took his men totally by surprise, as Arthur recollected:

Mounting his horse, he stood in the saddle and called out to all the men in a firm, strong voice: “Every man for himself!” Drawing his pistol from his holster, he laid it against his temple and pulled the trigger. In stunned silence we watched his lifeless body slide from the saddle and land in a crumpled heap in the snow. After a few moments to collect ourselves, we quietly wrapped his body in a blanket and buried him where he fell. We were now on our own.[11]

Thus began a terrible trial of survival for Arthur and his comrades. With the odds against him, he resolved to survive:

I knew that my faith in God would support me and that He would be with me no matter what happened. For the next three months, that knowledge was the only comfort and strength I would have.[12]

Over the next twelve weeks, Arthur trudged through the snow westward, away from Stalingrad, where an estimated 295,000 German soldiers had been killed or captured.[13] He suffered terrible cold and lack of food and shelter and saw his comrades fall and perish around him, but the worst danger was perhaps potential death or loss of body parts to frostbite. At one point, an officer had noticed his sad condition and found a spot on a sled to carry him along.

Arthur later described his condition toward the end of their retreat in the spring of 1943: “The pain in my feet and legs was so intense that I could no longer walk. The skin on my feet had fallen away, and there was horrible infection everywhere. The pain was terrible and excruciating, almost unbearable.”[14] Fortunately, he was soon shipped back to Germany and taken to a hospital where he received excellent care.

After months in the hospital, Arthur was given leave to visit his family in Tilsit for a month. The image of the bold hero returning to an enthusiastic welcome by adoring admirers at home was clearly not applicable in his case, as he later observed:

My arrival was a somber one, tears both of joy and of gratitude. . . . The effect Stalingrad had on me was evident in my limp and walking cane. My family also saw deep spiritual wounds, which would take time to heal. They saw the sadness in my eyes and steeliness in my composure that still held a lot inside. I was not the jovial soldier home on leave they had seen [the] last November.[15]

Because Arthur Naujoks’s physical condition improved, he was not released from the army but was given a training assignment. By the summer of 1944, he had recovered sufficiently to be sent again to the Eastern Front, which was creeping steadily toward Germany. There was little that he and his comrades could do to stop the advance of the seemingly innumerable soldiers of the Red Army.

Waltraut Naujoks married in 1944 in Tilsit. While visiting her parents-in-law in Elbing near Danzig, she learned that an air raid had occurred in Tilsit on April 20 and that her parents’ apartment had been destroyed. The Naujoks were the first Saints in Tilsit to lose their home. Even for faithful members of the Church, this could be a spiritual test, as she later explained: “We asked ourselves if we were not faithful enough for the Lord to protect us. We prayed long and hard to know why it had happened to us.” Later, the branch president’s home was also destroyed, and they knew that it did not happen because they were not faithful enough. “It just happened.” Waltraut remained in Elbing.[16]

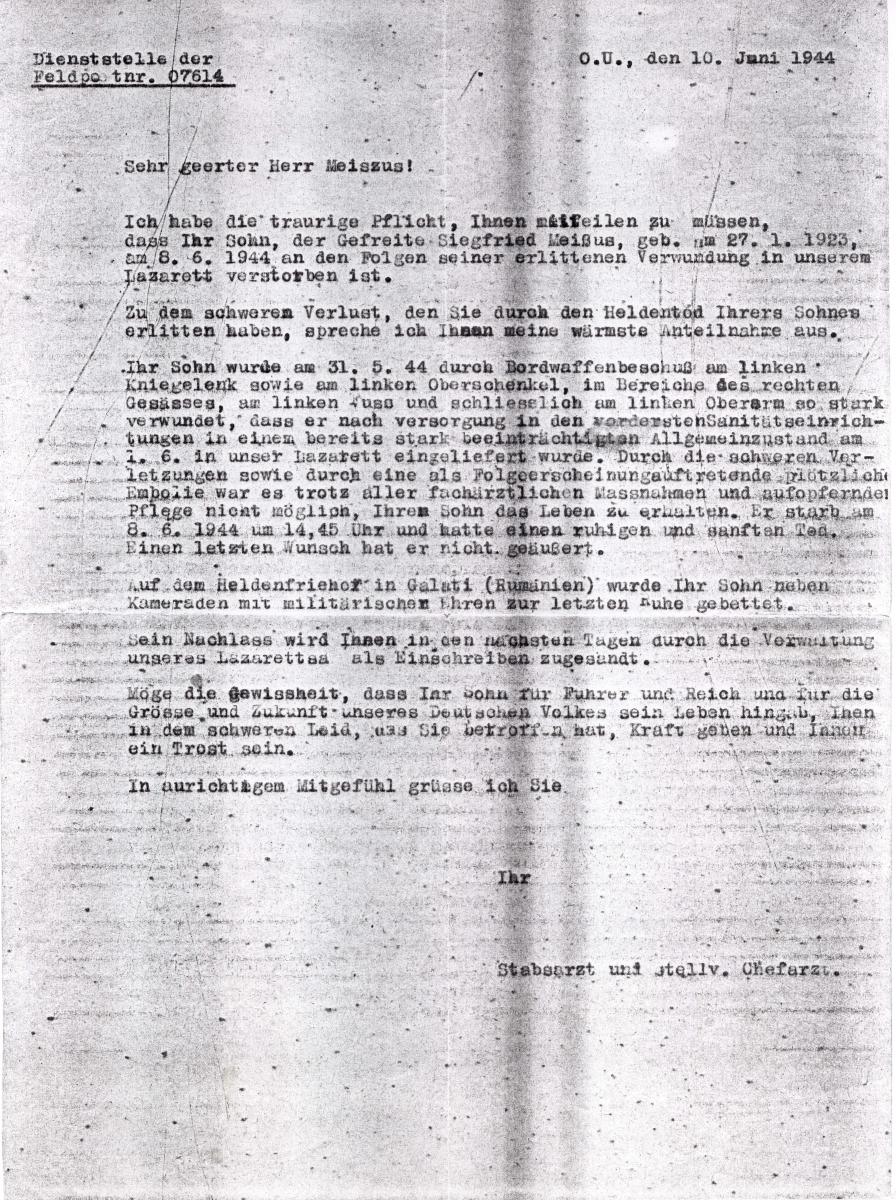

On July 24, 1944, the Tilsit Branch had a memorial service in the chapel for Helga Birth’s brother, Siegfried Meiszus, and for Heinz Milbrecht. The loss of faithful priesthood holders was hurting this and most other branches in the East German Mission. Later that evening, Helga decided to stay the night with her aunt rather than with her grandparents, Eduard and Anna Wachsmuth, with whom she had stayed many times before. During the night, a terrifying air raid took place, and the next day Helga stood staring at the rubble of the Wachsmuth home. It would be two weeks before the bodies of her grandparents could be removed from the rubble. Regarding her escape from certain death, she later stated, “I cannot even explain anymore how I felt. I only knew that my Father in Heaven had a different plan for me.”

In August 1944, Helga Meiszus Birth took the train to Berlin, where she began a term of missionary service that would last eighteen months. Paul Langheinrich, second counselor to the mission supervisor, had called her in April, but in accordance with the law, she was not allowed to leave her employment until she could find her own successor.[17]

Bruno Stroganoff’s occupational training program was not yet finished when he was drafted into the Waffen-SS, the elite combat troops under the command of Heinrich Himmler. Bruno had no way of knowing that he would soon be exposed to some of the more sinister happenings of the war on the Eastern Front:

When I saw what they did with the Jews, I could not believe my eyes. I did not see any sense in what I was ordered to do.[18] As soon as I realized what their [SS] methods were, a Hungarian and I fled but were soon caught in Czechoslovakia.[19] We then had to explain the situation to a judge in court. I was kept in prison in Krakau [Poland] in concentration camps.

Bruno Stroganoff could easily have lost his life. Desertion was punishable by death in every European country at the time. Being sent to a concentration camp was the closest thing to death and often did result in death. At one point in his incarceration, Bruno Stroganoff was sent to Dachau, one of the most infamous concentration camps. He explained: “In Dachau, I did not have to work in the concentration camp, but they treated me horribly.” He was one of many political prisoners there, of whom thousands died from 1933 to 1945. After making the rounds of numerous camps, Bruno had serious health problems that put him into a hospital in Heidelberg. Tuberculosis was part of the diagnosis. He underwent surgery, and by the time he had recovered, the war was over. The Americans took him prisoner, and he was not released until 1946.

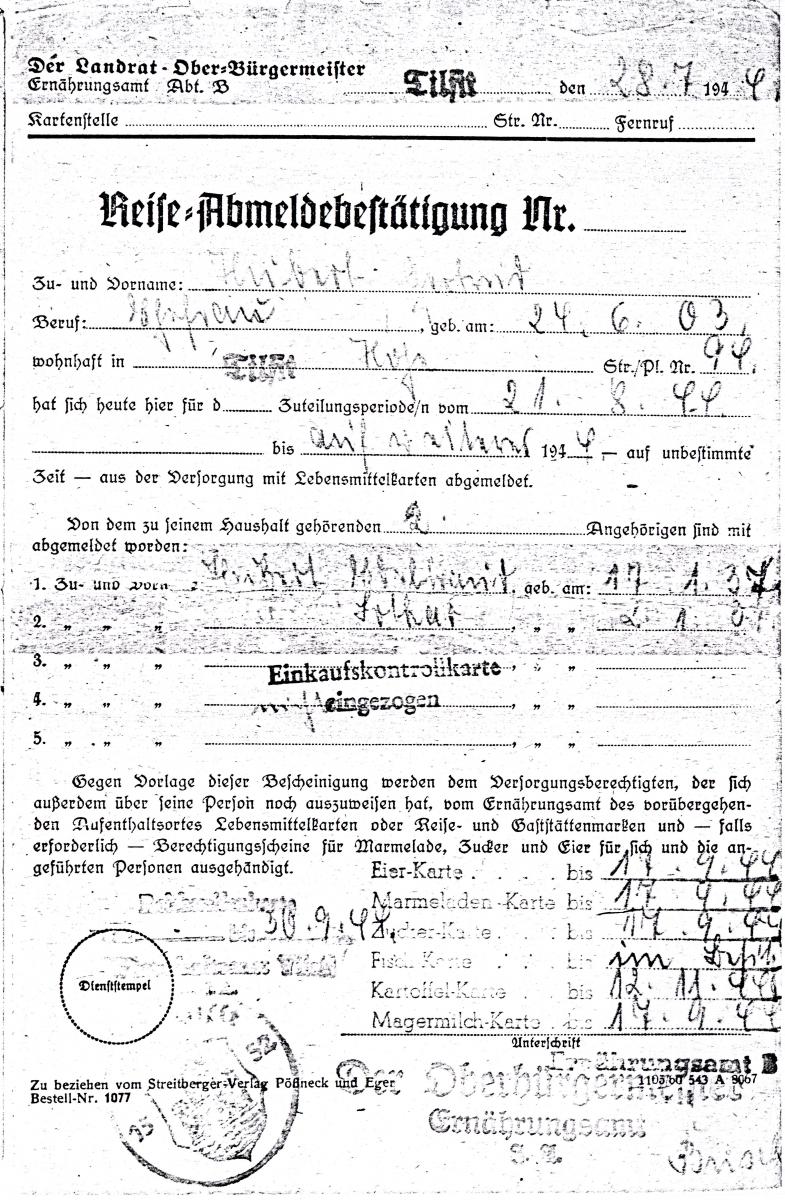

Refugees who expected to receive food ration stamps in a new location needed official permission to leave their homes. This certificate was issued to Gertrud Hubert when she left Tilsit with her son Lothar in July 1944. (L. Hubert)

Refugees who expected to receive food ration stamps in a new location needed official permission to leave their homes. This certificate was issued to Gertrud Hubert when she left Tilsit with her son Lothar in July 1944. (L. Hubert)

“I did not always keep the commandments during the war, but I never forgot that I was a member of the Church,” admitted Bruno Stroganoff. This is a reminder that the life of a soldier could be spiritually challenging. He continued, “During the war, I didn’t have any contact with the Church after I left home. I wasn’t allowed to carry the scriptures with me.” Like so many Latter-day Saint soldiers in the service of the Vaterland, Bruno was isolated from organized religion.

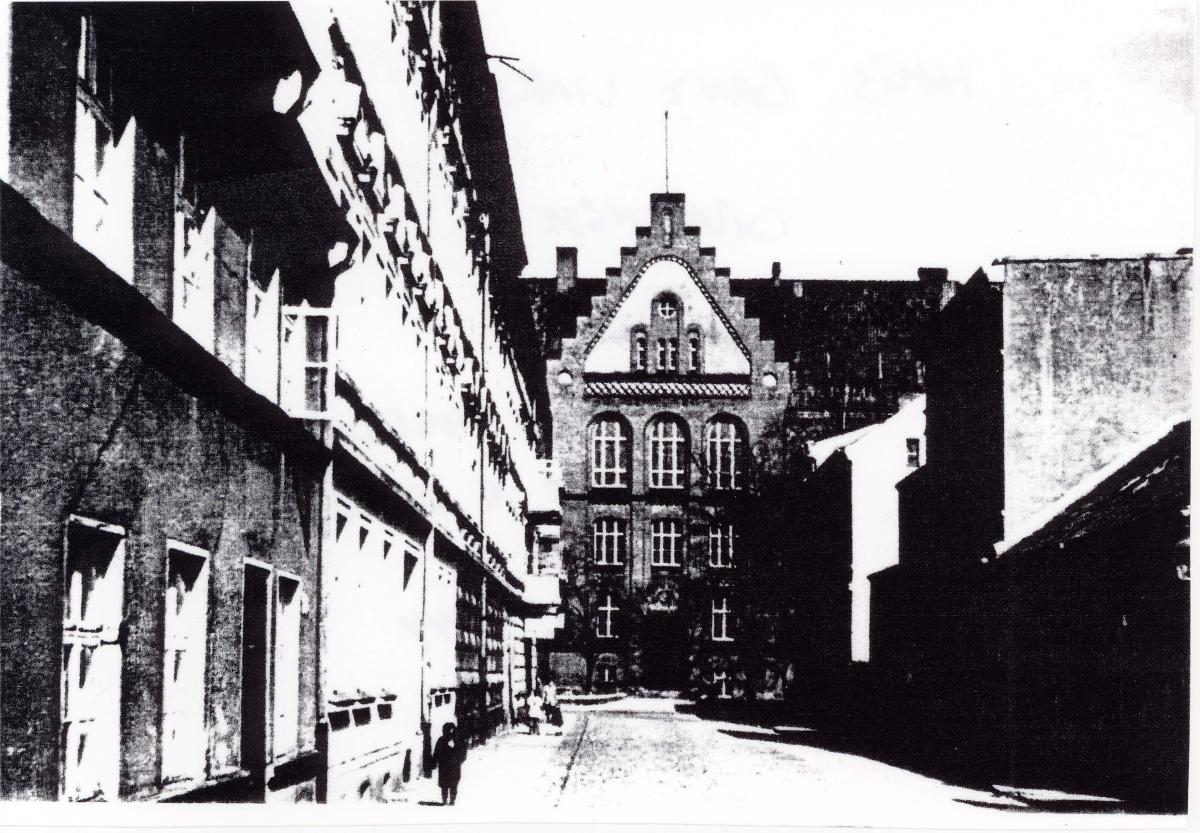

The house at the far left was the home of Sister Hedwig Hubert Bütow in Tilsit. It was bombed out in 1944. (L. Hubert)

The house at the far left was the home of Sister Hedwig Hubert Bütow in Tilsit. It was bombed out in 1944. (L. Hubert)

Sometime in the last year of the war, the Schulzke home was destroyed. Eva and her parents were in the habit of hiding in their basement when the air-raid alarms went off, except on that very night:

My mother had a feeling; she said we have to leave tonight, we cannot stay here, and she had the feeling to go to the farm. We went to members of the Church, and the same night we got bombed out, totally destroyed. If we had stayed at home that night, we would have been killed.

On July 24, 1944, Anna Maria Moderegger heard bombs fall on Tilsit and saw the glare of fires at night. She lived in Heinrichswalde (about eight miles from Tilsit), but decided to walk to town the next day to see what had happened. She described the scene:

I could hardly recognize the city. Entire streets were burning. People who had lost their homes and had escaped the basement shelters wandered about, crying out in desperation for their loved ones. Some were mourning their property, as they watched it go up in flames. They all seemed to have lost their minds.

The Schulzke family’s apartment (upper balcony) was bombed and burned out in late 1944. (E. Schulzke Bode)

The Schulzke family’s apartment (upper balcony) was bombed and burned out in late 1944. (E. Schulzke Bode)

She found that Branch President Otto Schulzke had survived, but his home had been destroyed. The Wachsmuths and their daughter, Anna, had been killed in the basement of their home. Brother Schulzke asked the surviving Saints to come to Tilsit for one last meeting on Sunday. They were to meet in the home of the Naujoks family. Sister Moderegger later described that event:

All of the survivors came. There were so few of us that we could all sit around two tables. We had a very modest meal, to which we had all contributed what we had. We had become a literal city of Enoch, because we literally shared everything. There was little left, but we did not speak of hunger. We also shared what clothing we had with those who had lost everything. Brother Schulzke gave the sermon. His vibrant testimony gave us all strength. We gained new courage. Nobody knew what the future would bring, but we relied on the Lord. All of us were discouraged and sad, but nobody was desperate or hopeless as were most people in those days. Toward the end, we had a moment of silence in honor of our fallen brethren who had once been the pride of their parents and the hope of our branch. Then we sang the hymn “God Be with You till We Meet Again.” We shook hands for the last time. For some it was the last good-bye. Brother Schulzke [a warden at the local prison] was ordered to take his prisoners to Königsberg. The survivors were given permission to leave the city. They fled to the countryside with their last possessions. Mothers with children were allowed to head westward. We no longer had a branch president. The Tilsit Branch had ceased to exist.[20]

In the fall of 1944, Red Army soldiers set foot on German soil for the first time, and stories of the brutal treatment of civilians at the hands of the Soviet invaders spread quickly. Despite the encouragement of neighbors to stay, Berta Augat felt strongly that they must flee. They loaded a good-sized wagon with their most treasured possessions and a good supply of food. As Heinz later recalled, the bed of the wagon bowed down under the weight, and one horse strained to pull the wagon:

The letter every family feared most: “I have the sad duty to inform you that your son, Corporal Siegfried Meisses [sic] . . . has died in our army hospital.” The letter detailed Siegfried’s five major wounds; after eight days in the hospital, he died, despite the best efforts of the surgeons. (H. Meiszus Birth Meyer)

The letter every family feared most: “I have the sad duty to inform you that your son, Corporal Siegfried Meisses [sic] . . . has died in our army hospital.” The letter detailed Siegfried’s five major wounds; after eight days in the hospital, he died, despite the best efforts of the surgeons. (H. Meiszus Birth Meyer)

The wagon looked like a pioneer wagon. We had those woven rugs, kind of like you would put a tent over to shield us from the cold. On our way back, there was a column of German tanks that approached, and they stopped, and we stopped, and we gave them some food, and one of the soldiers climbed over the fence onto a deserted farm and [found] another horse [to hitch to] our wagon.

The day before their departure, Sister Augat received a letter from her brother’s family. They had departed about six weeks earlier and had written to inform her that they had found temporary housing in Freiberg in Saxony. Ursula Augat recounted the following details about their exodus:

Then we went several days on this wagon, and then my mom said, “I can’t do this.” And she felt so strong. . . . She was guided by the Spirit all the time. She knew just what to do. She went to this train station and said, “Look, I’m [a] woman alone with two small children. I need to get on this train.” They said, “Absolutely not, unless you have a relative.” And she said, “Yes, I do, I have my brother there.” And she showed them the letter that she got the day before. [Without that] we would have not gotten onto the train.

The train they boarded was heading west, overcrowded with refugees attempting to flee for their lives yet bent on taking everything they could with them. According to Ursula,

I, myself, was very scared. I thought I was being crushed to death because people were standing so close together. And it was horrible. And I remember we were standing and always looking up to adults, and they were old men and women. And they looked at their watches and pocket watches, and they said, “Oh, boy, oh, boy, are we going to make it?” [The Soviets] were closing in, and our train went through, and nothing more. We just made it! Just made it!

After arriving in Freiberg in about January 1945, the Augats were given a room in the meetinghouse of the Freiberg Branch. For the first time, they experienced air-raid warnings and nights in the basement shelter. Also for the first time, they attended church meetings on a regular basis. Ursula was surprised to see the other members singing from hymnals, something she had never seen. “I knew all of the songs by heart. My mother had taught them to us at home.”

In the fall of 1944, Lothar Hubert (born 1939) was taken by his mother north to the city of Memel for a short time. From afar, they listened and watched the air raid taking place over Tilsit. Hubert told this story:

The next day, we went back to Tilsit together with my foster brother and we heard that in the Grabenstrasse, where my grandmother lived, the houses were destroyed. We cried. When we looked at the house, we could see the inside of the apartment from the street. I remember the kitchen cabinet that was still standing.[21]

When Sister Hubert decided to leave Tilsit for good in the fall of 1944, they needed specific permission from the city government. With that paper in hand, they headed west and south and experienced the end of the war in the town of Oberneuschönstein near the Czech border in Saxony. Several months later, they moved to Bernburg, Saxony, and soon found themselves living in what had been the Buchenwald Concentration Camp. Sister Hubert was joined there by her husband, Arthur, after he was released from an American POW camp. Their daughter, Klara, had been a prisoner of the British and likewise found her way to her parents at Buchenwald. Unfortunately, the sins of the concentration camp guards were visited upon the heads of these innocent civilians, in that they were required to help bury the bodies of Buchenwald inmates.

During the last few months of the war, the Lessing family was split up. Brother Lessing was away on police duty and daughter Ursula was employed by the German postal system and assigned to work at a railway station post office in Dirschau. Sister Lessing and the three youngest children moved west to Braunsberg, then on to Dirschau near Danzig to live with a relative. Sister Lessing’s parents, the Hübners, left the Kalwehlen farm and moved westward. The Hübner property may have been the first German Latter-day Saint home to be conquered by the invaders.

In March 1945, Emma Lessing took her three youngest children and began the trek west to escape the invaders. They were able to board a train and made it all the way (nearly three hundred miles) to the main station at Swinemünde, a port on the Baltic Sea. However, their timing could not have been worse. Just as the train pulled into the main station, where thousands of refugees were competing for places on trains bound for cities to the west, the air-raid sirens began to wail. As daughter Inge recalled,

When the alarm went off, there was panic in the station. People were running around trying to find a place to hide from the attack. We were still on the train, so my mother told my brothers and me, “Quick, get under the seats!” Then the bombs began to fall and it was terrible. I was only six at the time and don’t remember much of what happened. The next thing I knew was that a nurse or a Red Cross lady was holding my hand and leading me out of the railroad station. [author: should it be cited to Inge?]

The attack on Swinemünde on March 12, 1945, left approximately twenty-three thousand civilians dead. Emma Hübner Lessing and her sons Kurt (born 1932) and Fritz (born 1936) perished when the railroad station was destroyed. Somehow, Inge survived the attack unharmed. The names of her mother and her brothers are included in the roster of the dead buried in mass graves in the suburb of Golm, but most of the people killed that day could not be identified. This was the first tragedy that struck the Lessing family.

Despite the tremendous confusion in German provinces east of Berlin in the spring of 1945, Ursula Lessing remembered that the German mail system was still functioning fairly well. By then, she had been sent to a postal sorting station near the Baltic Sea and was working long days there, sorting thousands of pieces of mail each day. “It was a kind of camp facility. We lived in barracks. I had to memorize all of the names of towns in the east. And we got to eat lots of fish from the Baltic,” she explained.

When government services began to fail in April 1945, Ursula Lessing was released from her job in the postal system. She joined other refugees headed west, fleeing from the invading Red Army. On one occasion, she was riding a bicycle from Schönberg to Dassow. For all practical purposes, the war was over, but the following incident occurred and remained vivid in her memory:

All of a sudden we were in [the] woods there and everyone said, “Get off the road!” And we all went off and just laid flat in the woods and when we came out of those woods the Russians had shot the refugees in their wagons, their horses and wagons, and they had shot them to pieces. It was horrible. . . . In the woods they didn’t see anyone or anything so [we were] all right, but when we got out our horses were half dead and everyone was screaming.

Shaken but unharmed, Ursula continued her flight to the west.

Emma Hübner Lessing and her two sons are some of the thousands of victims of the March 12, 1945, air raid on Swinemünde who were buried in this mass grave. (21 March 2008 http://

Emma Hübner Lessing and her two sons are some of the thousands of victims of the March 12, 1945, air raid on Swinemünde who were buried in this mass grave. (21 March 2008 http://

In early 1945, Anna Maria Moderegger took her five-year-old son and found a train out of town. They were taken to Czechoslovakia and then used the only available transportation to take them west to southern Germany: their feet. They walked most of the way to Deggendorf, Bavaria. From there they found trains to Munich, Kaufbeuren, and Buchloe, where she met her husband and her daughter. She later wrote of the journey as the worst experience of her entire life, characterized by intense suffering.[22]

The Moderegger family members were reunited in Buchloe, Bavaria. In the summer of 1945, Brother Moderegger was given permission to establish a garden and landscaping business in Langen, just south of Frankfurt am Main. Anna Maria and her children joined him there a few months later. The first Saints in that town, they became the founding members of what was by 1946 a very large branch of the Church, consisting exclusively of refugees.[23]

On April 18, 1945, Arthur Naujoks narrowly missed being killed in a battle with the Soviets when he and his unit ran out of ammunition. His commanders told him that because they had nothing to fight with, their war was over, and they might as well leave. Arthur was armed with only a pistol when he headed west among a huge stream of refugees. His goals were to avoid capture by the Soviets and to survive.[24]

Near Neubrandenburg, he approached a checkpoint where SS soldiers were monitoring military traffic. Soldiers in good condition were being ordered to turn around and go back to fight the Soviets. Some had apparently refused and were hanged as deserters. Only wounded soldiers were allowed to pass and proceed westward. At that point, Arthur began to contemplate a terribly difficult option. After agonizing about the problem all night long, he decided to inflict a small wound upon himself in order to pass the guards and avoid execution. Later he would write about trying to listen to the still small voice to know what to do, but “my head filled with so much noise that this small voice could not be heard.”

He chose the fleshy part of his arm below the elbow and aimed his pistol carefully, in order to avoid serious damage. He pulled the trigger and nearly lost consciousness. Despite the simplicity of his wound, he was in shock. Fortunately, his calculations were good; he had missed the critical parts of the arm, but had bled enough to give the appearance of a serious wound. He thus faked his way past the guards and continued west to Schwerin and freedom. The Americans arrived in Schwerin while Arthur was there.

In western Germany, Ursula Lessing sought assistance from government agencies and the Red Cross to locate her parents and her siblings. She had last heard in 1945 that her father, Willi Lessing, was serving in the military police somewhere in Poland. Eventually she received a card from him; he was a POW in Soviet captivity. Unfortunately, he died in Leningrad, Russia, on September 20, 1948—still a prisoner of war. It is very likely that he had not learned that his wife and his two sons had been killed; only Ursula and Inge were still alive.

Ursula Lessing was finally able to locate her sister, Inge, in 1947. After the deaths of her mother and brothers, the little girl had been sent first to Denmark, then back to Germany after the war, and was living with an aunt. Until their reunion, Ursula had no idea what had become of Inge and the rest of the family. In the meantime, her grandparents, the Hübners, had made their way as far west as Danzig before the conquerors caught up with them. For some reason, they did not evacuate to the west. Carl Otto Hübner succumbed to malnutrition in Danzig on September 4, 1945.

When the war ended, the Augat family exodus had not yet concluded. According to Ursula and Heinz, they spent about nine months in Freiberg (where both of them were baptized on August 28, 1945), then in 1946 moved further west to Wolfsgrün, where the East German Mission leaders had been granted the use of a castle (a large villa) to house Latter-day Saint refugees. Nine months later, in 1947, Sister Augat took her children on another trip, this time to Langen, where they joined the largest Latter-day Saint refugee colony in Germany. Things were looking up for the Augats, whose husband and father finally joined them in 1949 when he returned from his POW term in the Soviet Union.

All Germans who declined to become Polish citizens in Tilsit were expelled from the territory by the end of 1946. The expellees likely included the remaining members of the Tilsit Branch of the Latter-day Saints, leaving the city of Tilsit with no Church representation. Today the city is known as Sovetsk, Russia.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Tilsit Branch did not survive World War II:

Therese —— bp. 4 Aug 1912; m. —— Bartschat; d. 23 Nov 1940, age 77, Memel, Tilsit (Sonntagsgruss, no. 11, 16 Mar 1941, 43)

Kurt Brahtz b. Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 24 May 1924; son of Fritz Karl Brahtz and Berta Emma Wachsmuth; bp. 29 Jun 1934; engineering corps; d. wounds army hospital Rela Aussig, Russia 14 Jan 1944; bur. Sovetzk, Russia (H. Meiszus Meyer; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Emil Eduard Ernst Berthold Flach b. Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 24 Nov 1924; son of Emil Eduard Hermann Erich Flach and Ida Helene Martha Hoost; bp. 17 Jun 1937; rifleman; d. wounds Lublin, Poland 19 Jan 1944 (H. Meiszus Meyer; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Berta Johanne Hoffmann b. Augustlauken, Ostpreussen, Preussen 4 Apr 1865; dau. of Karl Hoffmann and Henriette Dwillies; bp. 3 Dec 1916; m. Argelothen, Ostpreussen, Preussen, Eduard Wilhelm Wachsmuth; 9 children; k. air raid Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 24 Jul 1944 (IGI; AF; H. Meiszus Meyer)

Karl Otto Huebner b. Trapönen, Ragnit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 17 Nov 1867; son of Otto Wilhelm Hübner and Karoline Wilhelmine Zielinsky; bp. Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 26 May 1912; m. 25 or 26 Dec 1894 Motzwethen, Niederung, Ostpreussen, Preussen, Ida Minna Schlenther; 6 children; d. malnutrition as refugee Danzig Free City 4 Sep 1945 (U. Lessing Mudrow; IGI; AF)

Emma Agnes Hübner b. Trapönen, Ragnit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 25 Oct 1899; dau. of Carl Otto Huebner and Minna Ida Schlenther; bp. 8 Jul 1924; m. Wischwill, Pogegen, Lithuania 27 Jun 1926, Willi Lessing; 4 children; k. air raid Swinemünde, Pommern 12 Mar 1945; bur. Golm, Swinemünde, Pommern Mar 1945 (U. Lessing Mudrow; IGI; AF)

Marie Jokuschies b. Tutteln, Ostpreussen, Preussen 12 Jun 1867; dau. of Jurgies or Georg Jokuszies and Ermuthe Emilie Swars; bp. 3 Sep 1908; missing refugee 1945 (FHL Microfilm 271372, 1930/

Fritz Adolf Lessing b. 1 May 1936 Kallwehlen, Wischwill, Pogegen, Lithuania; son of Willi Lessing and Emma Agnes Huebner; k. air raid Swinemünde, Pommern 12 Mar 1945; bur. Golm, Swinemünde, Pommern (U. Lessing Mudrow; IGI; AF)

Kurt Erich Lessing b. Kallwehlen, Wischwill, Pogegen, Lithuania 29 Feb 1932; son of Willi Lessing and Emma Agnes Huebner; k. air raid Swinemünde, Pommern 12 Mar 1945; bur. Golm, Swinemünde, Pommern (U. Lessing Mudrow; IGI; AF)

Willi Lessing b. Lasdehnen, Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 17 Jul 1899; son of Hermann Gottfried Lessing and Maria Dilba; bp. 16 Jun 1926; m. Wischwill, Pogegen, Lithuania 27 Jun 1926, Emma Agnes Huebner; 4 children; d. POW Leningrad, Russia 20 Sep 1948; bur. Leningrad (U. Lessing Mudrow; IGI; AF)

Willi Lessing (U. Lessing Mudrow)

Willi Lessing (U. Lessing Mudrow)

Henry Martin Meiszus b. Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 17 Feb 1926; son of Martin Meiszus and Minna Berta Wachsmuth; MIA Normandy 1944 (H. Meiszus Meyer; IGI)

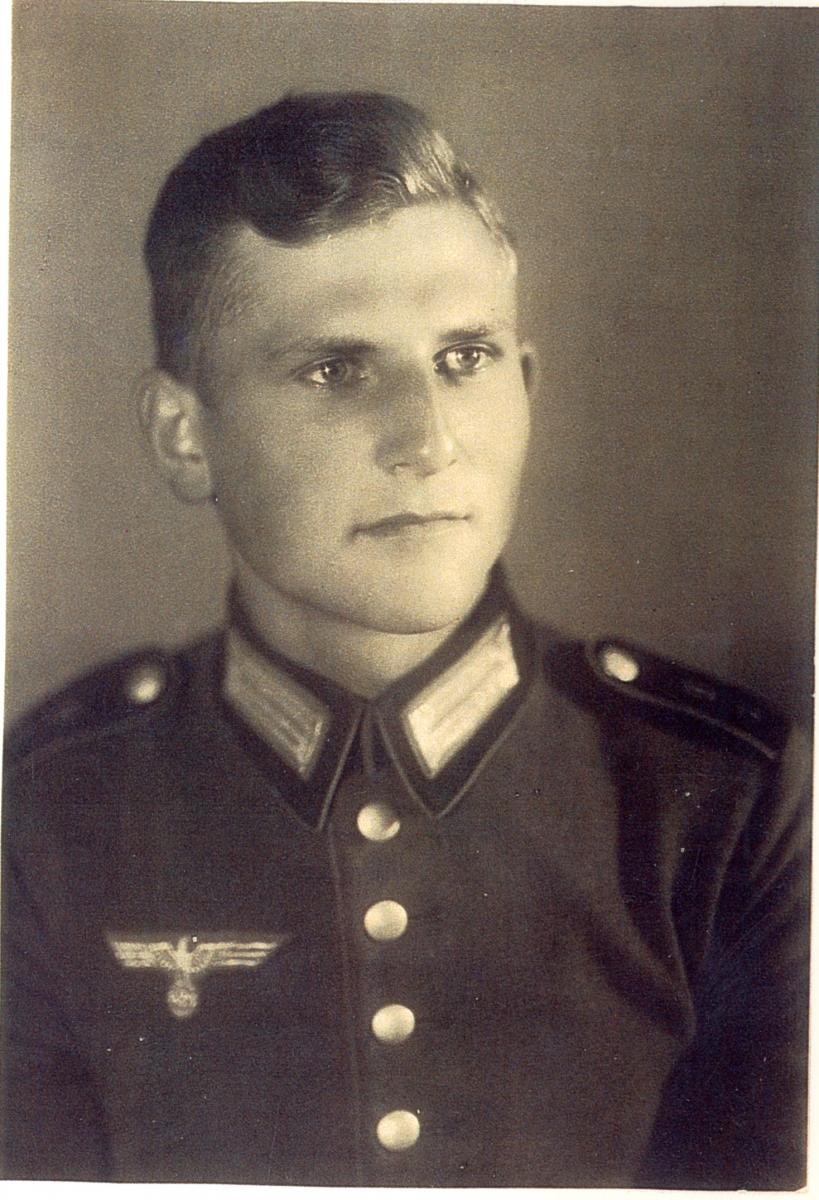

Siegfried Adalbert Meiszus b. Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 27 Jan 1923; son of Martin Meiszus and Minna Berta Wachsmuth; bp. 25 Jul 1931; d. wounds army hospital Romania 8 Jun 1944 (H. Meiszus Meyer; IGI)

Siegfried Meiszus (Helga M. Meyer)

Siegfried Meiszus (Helga M. Meyer)

Fritz Bruno Millbrecht b. Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 18 May 1922; son of Ludwig Millbrecht and Bertha Louise Pastowsky; k. in battle 2 Jun 1944 (H. Meiszus Meyer; FHL Microfilm 245233, 1930/

Karl Heinrich Millbrecht b. Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 21 May 1919; son of Ludwig Millbrecht and Bertha Louise Pastowsky; k. in battle Russia 1 Apr 1944 (H. Meiszus Meyer, FHL Microfilm 245233, 1930/

Fritz Negraszus b. ca. 1918; MIA (H. Meiszus Meyer)

Bertha Louise Pastowsky b. Meldienen, Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 5 Nov 1882; dau. of Hans Nuckmann and Wilhelmine Pastowsky; m. Laugallen, Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen ca. 1905, August Friedrich Raeder; 2m. Ludwig Millbrecht; d. 11 Jun 1945 (H. Meiszus Meyer; IGI)

Erich Kurt Pechbrenner b. Wischwill, Pogegen, Lithuania 2 Oct 1925; son of Fritz Pechbrenner and Ells Frieda Minna Hübner; non-commissioned officer; MIA Pulawy bridge head, Glogow Jan 1945 (U. Lessing Mudrow; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Olga Viktoria Romanowski b. 13 May 1881; dau. of J. Romanowski and F. Koresna; m. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen ca. 1922, Johann Kusmin Stroganoff; 1 child; disappeared (IGI)

Fritz Stanull b. Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen; m. Hedwig Anna —— ; k. in battle Russia 1943 or 1944 (H. Meiszus Meyer)

Anna Wachsmuth b. Ragnit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 4 Jan 1901; dau. of Eduard Wilhelm Wachsmuth and Berta Johanne Hoffmann; m. Altona, Schleswig-Holstein, Preussen 9 Jul 1937, Otto Hermann Paul Schulze; k. air raid Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 24 Jul 1944 (IGI; H. Meiszus Meyer)

Eduard Wilhelm Wachsmuth b. Schaaken, Ostpreussen, Preussen 24 Aug 1859; son of Heinrich Wachsmuth and Friederike Wilhelmine Gassner; bp. 24 Aug 1920 Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen; m. Heinrichswalde, Ostpreussen, Preussen 20 Oct 1889, Berta Johanne Hoffmann; 9 children; k. air raid Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 24 Jul 1944 (IGI; AF; H. Meiszus Meyer; www.volksbund.de)

Adelbert Zapick b. 1916; gef. (MIA) Russia 1941 (U. Lessing)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Waltraut Naujoks Schibblack, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, February 15, 2008; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski, and transcript or audio version of the interview is in author’s collection.

[3] Eva Schulzke Bode, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, February 9, 2007.

[4] Helga Meiszus Meyer, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, February 15, 2008.

[5] Arthur O. Naujoks Jr. and Michael S. Eldredge, Shades of Gray: Memoirs of a Prussian Saint on the Eastern Front (Salt Lake City: Mill Creek Press, 2004), 29.

[6] Ibid., 51.

[7] Bruno Stroganoff, interview by Jennifer Heckmann in German, Neckargemünd, Germany, August 20, 2006.

[8] Ursula Lessing Mudrow, interview by the author, Ogden, Utah, March 9, 2007.

[9] Ursula Augat Black and Heinz Augat, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, December 1, 2006.

[10] Naujoks and Eldredge, Shades of Gray, 56.

[11] Ibid., 115.

[12] Ibid.

[13] William L. Shirer, The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich: A History of Nazi Germany (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1990), 932.

[14] Naujoks and Eldredge, Shades of Gray, 132–33.

[15] Ibid., 139.

[16] For a description of subsequent events in Waltraut’s life, see the chapter on the Elbing Branch of the Danzig District.

[17] For a report of her activities in the mission home in Berlin, see the East German Mission chapter.

[18] The “Final Solution of the Jewish Problem” (a euphemism for the murder of European Jews) was well under way by that time.

[19] Men from many European countries were recruited by the Waffen-SS. One of the organization’s prime arguments was that the Waffen-SS was responsible for the eradication of communism in Europe, specifically in the Soviet Union. Bruno himself was not a German but the son of Latvian citizens.

[20] Anna Maria Moderegger, “Mein Weg in die Freiheit” (unpublished history, 1977), 2–3; private collection; trans. the author. In the introduction of her autobiography, Sister Moderegger made this comment: “If my readers believe that I had included too much detail in the story of my flight from Saxony to Bavaria, they should remember that this was the most violent and disturbing experience of my entire life.”

[21] Lothar Hubert, interview by the author in German, Schwerin, Germany, August 17, 2006.

[22] Moderegger, “Mein Weg in die Freiheit,” 5–17.

[23] Ibid., 23.

[24] Naujoks and Eldredge, Shades of Gray, 189.