Stettin Branch, Stettin District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 459-77.

One of the largest and strongest branches in the East German Mission, the Stettin Branch, was about forty years old when World War II began in 1939. With a substantial number of priesthood holders, it was the logical administrative center of the Stettin District. The city of Stettin was home to approximately two hundred sixty thousand people at the time.

| Stettin Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 12 |

| Priests | 14 |

| Teachers | 17 |

| Deacons | 18 |

| Other Adult Males | 75 |

| Adult Females | 194 |

| Male Children | 17 |

| Female Children | 12 |

| Total | 359 |

The Stettin Branch held its meetings in rented rooms at Hohenzollernstrasse 32. Elli Zechert Polzin (born 1913) later described the setting in these words:

Before the Church rented these rooms and made them pretty for us, it was a cow shed. This place was the second Hinterhaus. It was a very long building, and . . . there was a sign attached to the first building on the street; it was black with white lettering. Inside, the building was divided into smaller rooms. The first rooms one could see were the cloak room and a small classroom. On the right side was the chapel with a podium and a curtain, which one could move. I remember a picture of Christ hanging on the wall.[2]

Margarethe Dretke (born 1912) remembered that the branch had both a piano and a pump organ in those days. “We heated the large room in the building with wood and coal that members contributed,” she recalled.[3]

Heinz Winter (born 1920) explained that the chapel was usually filled and a classroom was used as an overflow area. Because there was no microphone in the room, the speakers had to speak very loudly.[4] Heinz also recalled that after the meetings, groups of Latter-day Saints walked toward home, often stopping at street corners, where “more meetings were held before we went our separate ways. People took each other home, and that was really nice.”

Regarding the schedule of meetings, Elli Polzin recalled that Sunday School began at 10:00 a.m., preceded by a leadership meeting. Sacrament meeting took place in the evening at seven o’clock. The Relief Society met on Tuesday evenings and MIA on Thursday evenings. She recalls an average attendance on Sunday of about one hundred persons.

Elli Polzin also recalled the departure of the American missionaries in August 1939: “We all cried when we said our good-byes in the branch. We hoped that it would not take long until they were allowed to come back.” Elli Zechert had married Hans Alfred Polzin in 1936. A daughter was born to them in 1937 and a son in 1940. Hans was drafted in May of that year and was gone for nearly ten years, except for a few furloughs during the war. The hairdressing business they had operated had to be closed down, and his wages as a soldier were substantially less than their business income, but she made ends meet for herself and the children in his absence.

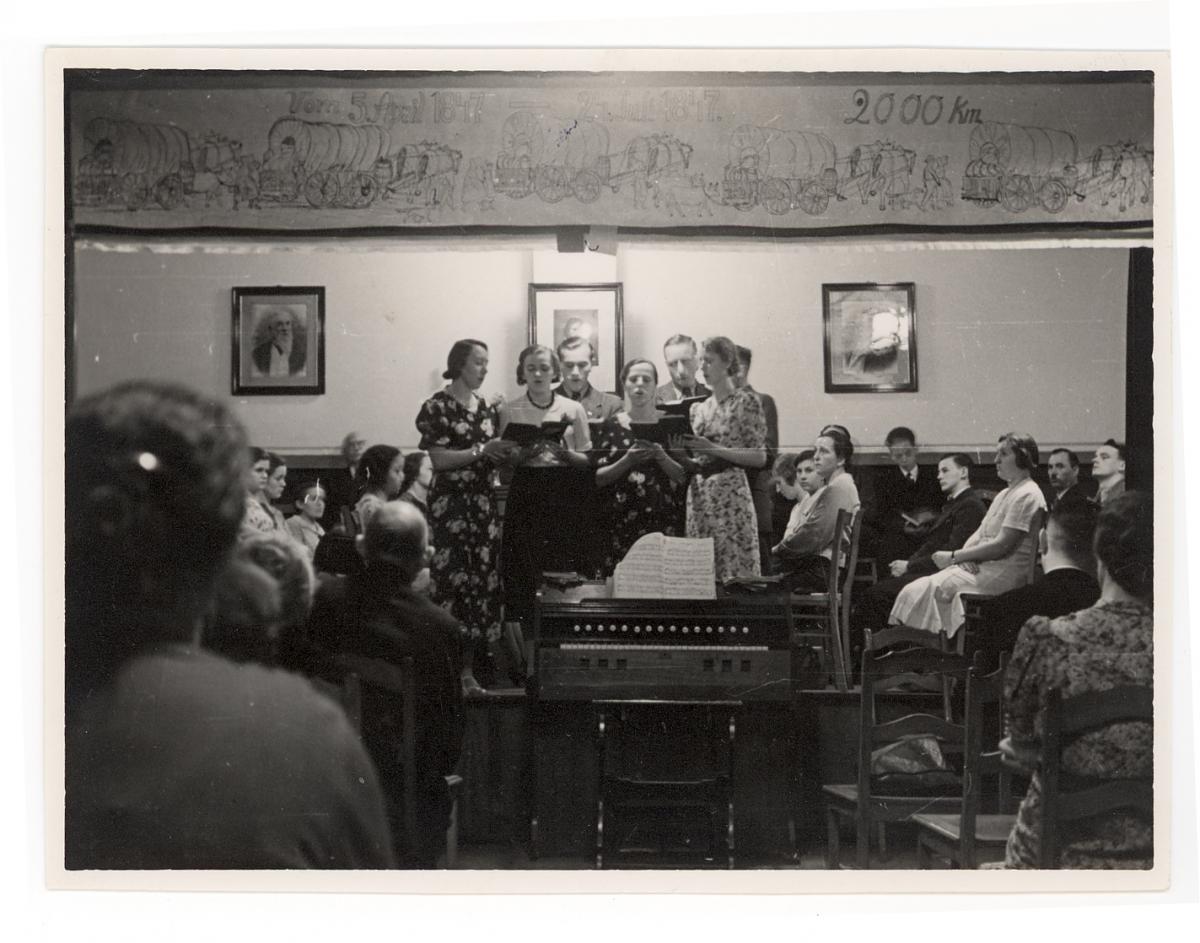

The interior of the Stettin Branch rooms at Hohenzollernstrasse 32 (I. Boehme)

The interior of the Stettin Branch rooms at Hohenzollernstrasse 32 (I. Boehme)

Young Dieter Berndt (born 1938) recalled the branch as a “big family.” He also remembered that when the children filed out of the main meeting room to their classes, they did so very reverently and orderly, namely, with their hands behind their backs “with a bit of a military air.”[5]

Only six years old when the war began, Ruth Krakow (born 1933) later recalled being scared to be alone after her father left for military service and her mother was assigned to work in the post office:

As a child in the war, I was very tense. My mother . . . had to leave very early for work. I had to take the train to school every morning, and I went alone. After school I went to my grandmother’s home, where I stayed until my mother picked me up late in the evening. I was scared being alone so much.[6]

Waltraut Kuehne (born 1929) was inducted into the Jungvolk with the rest of her classmates when she turned ten. She later recalled being only minimally active in the organization: “I didn’t have any uniform. I attended meetings but mostly sports meetings and that. I never went to any other meetings because my parents didn’t believe in it.”[7]

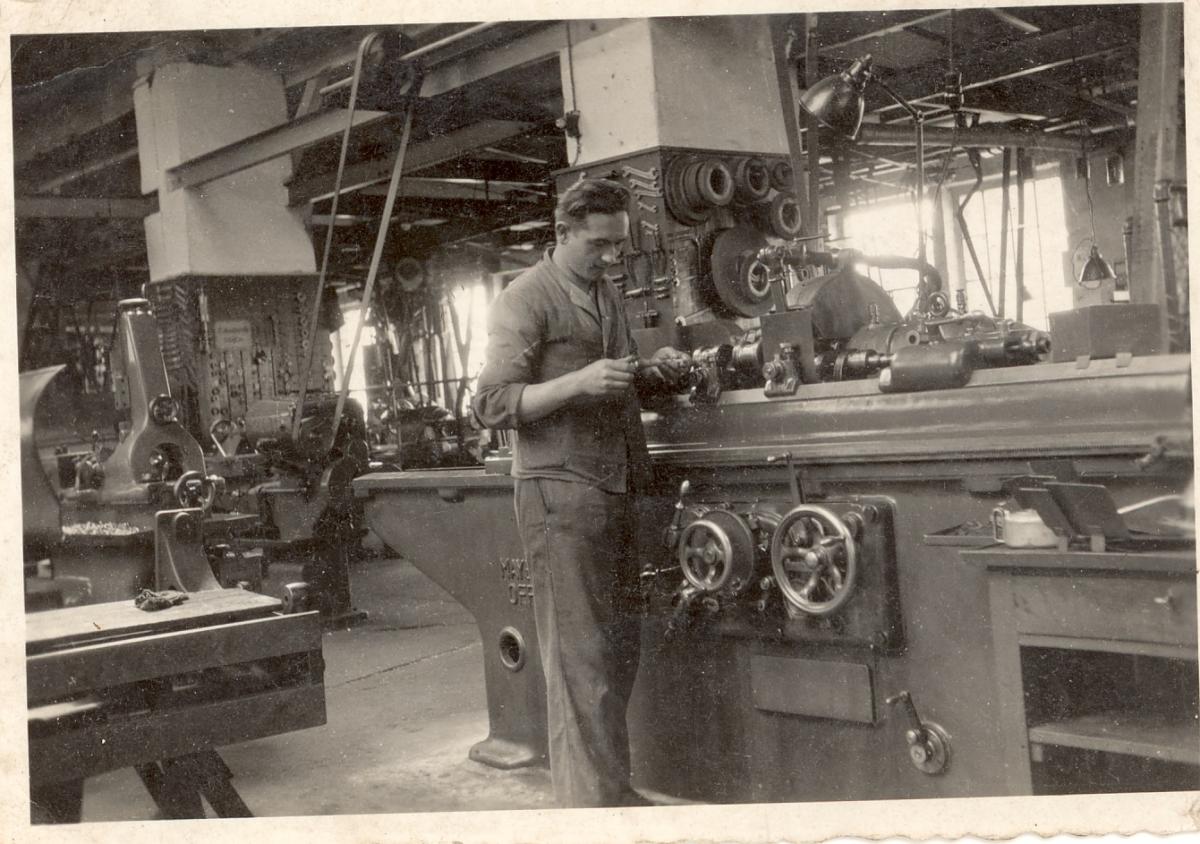

Margarethe Dretke’s husband, Willi, had been the branch president and a member of the district presidency in Stettin. He was a lathe operator and worked in a factory that produced items critical to the war effort. This allowed him to be exempt from military service for the entire war, though the army attempted to draft him at least once.

A barber by trade, Alfred Bork (born 1920) was a teacher in the Aaronic Priesthood when he was drafted by the Wehrmacht very early in the war. A devout Latter-day Saint, he was planning to serve a mission some day and was soon to be engaged to a pretty young lady in the Königsberg Branch. These plans were put on hold when he donned the uniform of the German army. An avid writer, Alfred kept two journals—one for matters of daily life and military service and one for religious experiences and thoughts. The entry dated July 30, 1939, in his religious journal is indicative of the spirit of this young man:

Today was a beautiful Sunday for us. Three-quarters of the Stettin Saints traveled to Berlin to hear Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith and his wife speak. . . . The high point of the meeting came when this apostle stood to give us his message. . . . We were all shocked to hear that this will be the last time we hear Pres. Alfred C. Rees speak, because he is being released from his mission. . . . Pres. Rees shook my hand and said these words to me: “Brother, you will be called on a mission soon.” . . . When I shook the hand of Apostle Joseph Fielding Smith, I felt the Holy Ghost flow over me, as if he were confirming the words spoken to me by President Rees.[8]

Further entries in Alfred’s religious diary recount visits to many branches around Germany and Austria. He sought out the local Saints every time he could. In several entries, he pled with the Lord that he might never take another human life. He was fortunate to have several assignments away from combat zones and to not carry a rifle for much of his time in the service of his country.[9]

Heinz Winter had been in the Stettin Branch Boy Scout troop in 1934, when the German government banned all such groups in favor of the new Hitler Youth program. At first, Heinz resisted joining the organization but then found out that there was a navy arm of the Hitler Youth. This he joined and was enthusiastic about the water sports. This interest guided his path into and within the German military.

When Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939, Heinz Winter was aboard a merchant vessel at the eastern end of the Baltic Sea. He was finishing a tour of duty that lasted two years and hoped to become a merchant marine engineer. On Hitler’s birthday that year, April 20, 1939, Heinz had survived an accident that sank his ship. According to his recollection, “we were passing a reef, and it ripped open the whole side of the ship, and I was in the engine room. I could see the water coming in like a waterfall.” The crew of thirty men managed to get off safely before the ship went down.

The fact that Latter-day Saint meetinghouses did not look like the traditional Christian churches in Germany is evident in the recollections of Gerda Stenz (born 1921), who was introduced to the Church by her future husband, Heinz Winter. He was back home for eighteen months of additional navy training. When he took her to see the main building on Hohenzollernstrasse 32, in the second Hinterhaus, she wondered: “It didn’t look like a church to me. So I was really anxious what it would be [like] inside.”[10] As she became acquainted with the Church and the branch, the physical setting no longer bothered her, and she was baptized in 1941.

The general minutes of the Stettin Branch survived the war. The branch secretary was meticulous in his record-keeping, including the names of all persons who presided at meetings, prayed, gave talks, or otherwise contributed to the worship services. The attendance figures for the years 1940 through early 1943 show an average of sixty to sixty-five persons in sacrament meeting.[11]

The German army invaded the Soviet Union on Sunday, June 22, 1941. Alfred Bork had the dubious privilege of participating in the invasion and made note of it in his diary:

June 22, 1941, Sunday: At 3:15 a.m. we were the first troops to cross the border into Russia. The enemy artillery fire was quite intense. Six men of our company were killed, including our company commander. When our artillery responded at 3:15 a.m., I ran with my horse from our hiding place behind a house through the forest to the Bug River in order to cross the river with the first boat. The Russian artillery immediately opened fire. As I was running through the forest holding on to my horse, I tripped and fell. At that moment, a shell landed just seven feet from me, and a piece of shrapnel hit the horse in the chest—right at the point where I had been running alongside of him. I then jumped up again and ran to the Bug River. Just as I got there the first boat pushed off, so I had to go with the second boat. When the first boat reached midstream, it received a direct hit and went down. I thank the Lord for saving me in this amazing way.[12]

One month later, Alfred Bork was shot through the lung and was taken to the rear. During his recovery, he spent time in Stettin and in Vienna, where he visited the branch meetings. He was back in Russia with his unit in December 1941.[13]

Heinz Winter in the uniform of the German Navy (H. Winter)

Heinz Winter in the uniform of the German Navy (H. Winter)

One Sunday, Alfred Bork was on his way to Stettin, and his train was held over in Küstrin for five hours. He went looking for a branch of the Church (not knowing that there was none there) and while doing so asked directions of an older lady (seventy-six years old). She knew nothing about the Church, but they conversed for a few minutes about religion while standing at an intersection. Minutes after they parted, Alfred felt inspired to return to that intersection and found her coming back to that place as well. She then invited him to her home. He wrote the following in his diary:

We talked about God and His word, then I got out my Bible that I always have with me. We had a fine conversation. She was a very sincere woman who wished to obey God and serve Him. She had suffered through many trials with her husband, who was a drunkard. She had given birth to retarded children because of her husband’s alcoholism. . . . But she was a happy person. . . . She told me, “You are a nice and sweet young man, and you have brought the sun into my home.” And I thank God that I was allowed to do this.[14]

Hans Polzin happened to be home on leave one night in 1942 when a bomb hit the pharmacy down the street. His family had chosen to stay in their apartment that evening rather than to seek shelter in the basement. The force of the explosion in the pharmacy sent them all flying off of the couch. As his wife, Elli, later explained, “We really thought that we would not make it. We prayed and held each other close.” At the time, they were living in the town of Finkenwalde, about eight miles from downtown Stettin.

Heinz Winter and Gerda Stenz were married on the her birthday, August 5, 1942. Gerda had overcome many obstacles to find a wedding dress, shoes, roses, food, and a suit for Heinz. Years later, she described her wedding day:

After hunting for many items for several months, the big day finally came. [Heinz] and his father came with the horse-drawn buggy to pick my father and me up to go to the Standesamt (justice of the peace) to be married. The justice was so serious that I could not stop laughing during the whole ceremony. We [were given] the book Mein Kampf. . . . When we got home, I got dressed in my bridal gown. I can hardly remember it because it was like a dream to me. I was beautiful, weighing only 95 lbs.; my dress was made out of silk and lace. We both were good looking, [Heinz] was only 156 lbs., thin and handsome. . . . At 4 p.m. in the afternoon our church wedding was. . . . Willy Dretke, the branch president, married us.[15]

Following five days spent with his bride, Heinz Winter was shipped off to Nantes, France, where he was assigned to a tanker. While the ship was being repaired, it was attacked and sunk. Heinz never went to sea on that ship, and the same fate claimed the next ship to which he was assigned. During his travels to and from various ports, Heinz once found himself in Amsterdam, where he set out to find the local branch. He was successful in doing so and walked into an apartment where fifteen to twenty men were holding a meeting. He later described the precarious event:

I was wearing my regular blue navy uniform and had a pistol on my belt. That was important. I came there as a German soldier. First, there was a little quiet, and I looked at them quietly. Now, I couldn’t really say much because I couldn’t speak their language a lot. But finally they all sat down, and I took my belt off and hung it up on the clothes rack, and they all gasped. . . . The meeting was pretty nice. After a while we shook hands and said good-bye, and then I never saw them again.[16]

His visit in the Amsterdam Branch was a rare treat for Heinz Winter. Otherwise, he was able to attend church only when home on leave, which happened about once a year. He had no scriptures with him and never had contact away from home with any German sailors or soldiers who were Latter-day Saints.

Members of the Stettin Branch on an outing for Ascension Day in about 1939

Members of the Stettin Branch on an outing for Ascension Day in about 1939

The first contact for Anna Kopischke (born 1924) with the Church came through an elderly member. As she later recalled: “Sister Kuehne was about eighty years old. She came to pick up her grandson to go to Sunday School, and they invited my brother to go along. He came back very enthusiastic and wanted me to go with them the next time.” The year was 1942, and Anna’s entire family eventually became acquainted with the gospel. She and her parents, Erich and Meta Kopischke, were baptized on September 26, 1942. The ceremony was conducted at a Stettin lake called Glambecksee under the direction of Ernst Winter. Anna later recalled, “I remember being wet even before we went into the water, because the weather was so bad that day. . . . Even though it was wet that day, the moment I went into the water, it was warm and it did not matter.”[17]

Ruth Krakow once traveled with her grandmother by train from Stettin to Breslau to visit an uncle. On the way, her grandmother suddenly left the first passenger car where there were empty seats and took Ruth to the last car, where there were no available seats and they had to stand. As Ruth recounted, “We had not been in the back for very long when we were thrown around the train and the luggage fell on us. We later saw that two trains had collided. Had we stayed in the first car we would all have died. . . . This experience helped us build a strong testimony.”

Sieglinde Dammaschke (born 1937) and her younger siblings were not safe in Stettin when the bombs began to fall. Her father was in the army so her mother took the family to Hamburg (180 miles to the west). Unfortunately, it was no safer there because the city was attacked on many occasions. Sieglinde recalled that her mother had difficulty waking her children up to take them to the basement. Apparently, the local block warden chastised her for considering leaving her children in bed when the sirens went off. The next time, she got them out and downstairs, later learning that a bomb had come through the roof and landed in their apartment.

On another occasion, the Dammaschkes’ apartment house was hit, and they could not escape because the basement door was blocked by debris. They utilized the holes cut through the walls into adjacent basements to move through the block.[18] At the end of the row of apartment houses, they learned that the fires outside were too severe to allow them to exit, so they retraced their path through the basements to another exit. “I don’t know how we ever got out of there,” explained Sieglinde. After another raid, she and her siblings were sent to an open area near the Elbe River to wait until it was safe to move through the streets. The Dammaschke family was bombed out three times in Hamburg before returning to Stettin, a city they considered safer.[19]

Waltraut Kuehne’s parents, Georg and Margarete, lost all of their property on April 20, 1942, in an air raid that nearly took their lives as well. Waltraut described the terrifying incident in these words:

We lived on the top floor, and a phosphorus bomb hit the bedroom of our apartment, and it was in flames right away. We didn’t get out [of the basement] until the all-clear siren went on. Where we lived there were only seven houses on the street, big apartment houses. Because bombers [probably knew] the whole street was military buildings, maybe they wanted to hit them, . . . but nothing military got hit there, but all seven of [the apartment houses] were heavily damaged. There were no stairs left to go up and rescue anything out of the apartment. . . . My sister Renate had only a doll when she went into the basement, and when the air raid was over and we got out, she only had a leg from the doll left in her hand.

When her school was destroyed in an air raid, Waltraut Kuehne was sent to the city of Kolberg (fifty-five miles to the northeast) to complete the school year. Back in Stettin, she was then pressed into service digging antitank ditches around the city. A year later, she was called to do her Pflichtjahr for the government and found herself assigned to a hotel in Heringsdorf where school children were housed.[20] There she served for seven months as a cook and cleaning lady. When the Red Army approached the area, she was released from her service and sent back to Stettin.

Heinz and Gerda Winter’s first son, Eberhard, was born in 1943. Heinz came home on leave from France with a suitcase full of food. Just after he left again, Eberhard contracted a serious illness and was in a hospital in Finkenwalde for six weeks. Gerda made the trip to the hospital every day (a return trip that took all day). She recalled her fears for her son: “I surely prayed hard for his recovery.” Fortunately, no operation was needed.[21] Soon thereafter, Gerda was evacuated to the town of Christinenberg, about fifteen miles to the northeast. She stayed there for more than a year and had no contact with the Stettin Branch, with the exception of a woman who visited her once. There was no other branch in the vicinity.

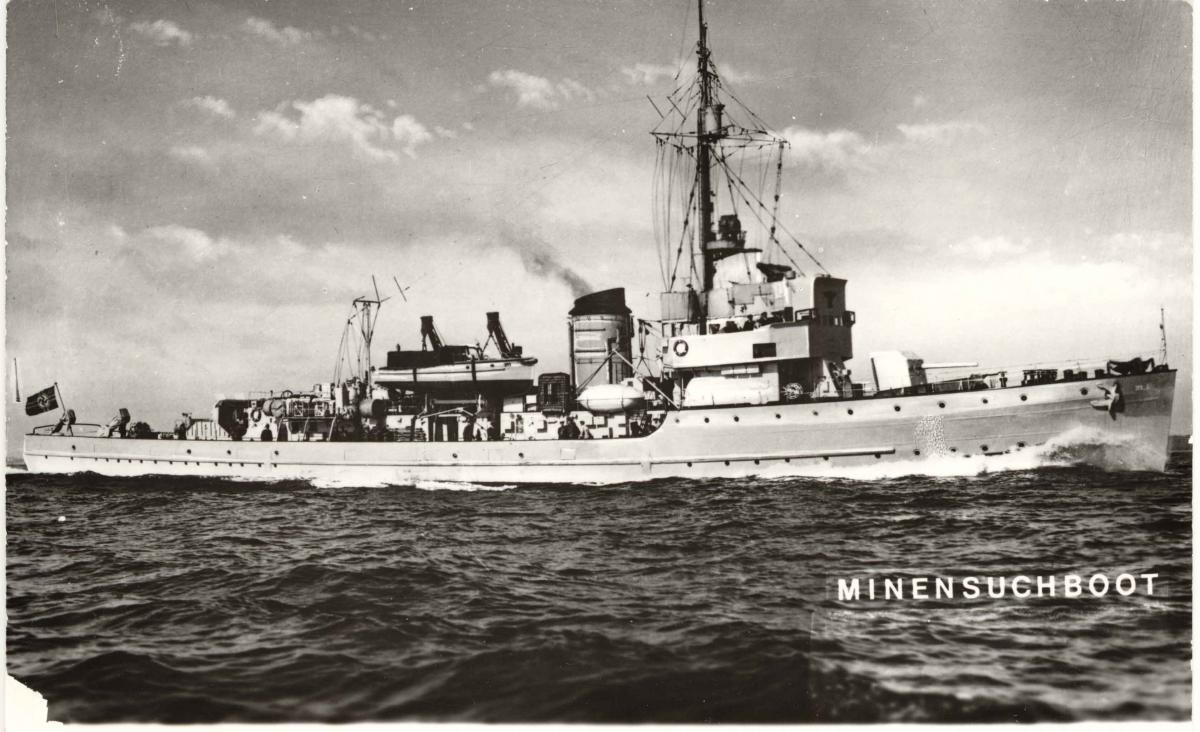

For most of the year 1943, Heinz Winter was stationed in the French harbors of Nantes, Brest, and Calais. In Brest, the Germans had constructed enormous submarine pens, where Heinz and his fellow sailors took refuge during the constant Allied air raids. Toward the end of the year, Heinz was assigned to a minesweeper patrolling the French coast of the English Channel. For ten months, his ship with its crew of seventy-five was under fire from sea and air. As he later explained, “We had [shrapnel] holes all over the ship. Every night we would weld plates of steel over them as repairs then paint them. The next morning, off we went again!”

During that ten-month tour of duty, nearly three hundred men who served aboard Heinz’s vessel were killed or wounded, but Heinz never suffered a scratch. He later stated, “If I had a scratch, I would have gotten a medal.” He worked a twelve-hour shift each day—the first six hours in the engine room and the next six on deck on fire patrol or doing repairs. From their position along the French coast, Heinz could see across the Channel to England. Every ship was visible. By the time he left that ship, his rank was equivalent to that of an ensign in the United States Navy.

Heinz Winter served aboard a minesweeper of this class in the English Channel (H. Winter)

Heinz Winter served aboard a minesweeper of this class in the English Channel (H. Winter)

Anni Bauer (born 1925) had moved to Stettin from Neubrandenburg to work and soon became an enthusiastic member of the Stettin Branch. By 1943, due to the absence of so many men in the Wehrmacht and so many women and elderly members of the branch (who had moved away from the city to escape the air raids), Anni took on several Church responsibilities: “I was doing just about every secretarial job in our [branch], except for Primary. Most of my free time was spent with the branch president, helping him to balance his financial records and reports. . . . Relief Society I also taught once a month.”[22]

Thea Bork (born 1931) recalled that government agents attended Church meetings on occasion, but apparently they did not disturb the proceedings. She also explained that they were not allowed to sing certain hymns (those featuring such “Jewish” words as Zion and Israel). “We circled the [hymn] numbers and knew that we should choose others.”[23]

The branch meeting minutes include a sad entry for 1943: “During the night of April 20–21, Stettin was attacked from the air. In this attack our meeting rooms were damaged.” The last meeting held at that location took place on April 25, after which the police declared the building unsafe and off limits.[24] The record then states that future meetings would be held in the homes of member families. During the same air raid, the following members lost their homes: Gertrud Schmidt, Julius Schmidt, Gerda Wittkopp, the Heinz Winter family, and the Georg Kühne family.

Elli Polzin and her children were evacuated to the town of Gielow (about ninety miles west of Stettin) in 1943. There she lost touch with the branch but had periodic meetings with the Gabrecht family, who had also gone there from Stettin.

The women and girls of the Stettin Branch gathered together for a Mother’s Day photograph in 1939.

The women and girls of the Stettin Branch gathered together for a Mother’s Day photograph in 1939.

Otto Bork was activated from his reserve status and assigned to supervise a camp of Soviet POWs near Grimmen, north of Demmin (about seventy miles northwest of Stettin). He was allowed to move his family to Demmin. From that time until the end of the war, Brother Bork spent most of his time at the POW camp. In Demmin, his wife and the three youngest children (son Hellmut and daughters Thea and Ruth) attended Church meetings with the tiny branch. “We met in the branch president’s home, and I don’t think that there were more than ten people most Sundays,” recalled Ruth.[25]

Just as all other German cities, Stettin was under strict blackout regulations at night for most of the war. In order to be seen on the streets in the pitch dark, pedestrians wore florescent badges on their outer clothing. According to Gerda Stenz Winter:

We could see when somebody was coming. We always walked because we had no other transportation. We were never afraid that we would be molested. It never occurred to anybody that maybe you were afraid that somebody would do something to you—including women walking alone.

When the meetinghouse was no longer available to the branch, members met in the villa owned by a Sister Schroeder. In her large living room they held only a sacrament meeting. There were still enough older men in the city to preside and to administer the sacrament. “Many younger people talked to me about what they had always done together with the branch before the war started,” Anna Kopischke recalled. Many branch activities and programs went by the wayside due to the restrictions imposed by wartime conditions.

“The air raids were horrible for me,” recalled Ruth Krakow. “We lived on the fifth floor of our building, and the shelter was in the basement. We were very scared because we thought that the house might fall on us when a bomb hit it.” There were a few public shelters in downtown Stettin for use by people away from home, and signs directed people to those shelters. “In every home there was a man who was responsible to ensure that everybody in the building was safe in the basement and not upstairs in their apartments,” according to Ruth.[26] The Krakow home was destroyed in the night of April 30, 1943. “That night, it seemed to me that we would never leave the shelter.” Fortunately, there was time to escape from the basement while the fire engulfed the upper floors of their apartment house. Following the destruction of their home, the Krakows moved to Neubrandenburg, where Ruth’s other grandmother lived.

The branch meeting minutes include a “joyous announcement” dated November 22, 1943: Branch meetings were to begin again at 4:00 p.m. on November 28 in the rooms of the Evangelical Free Church at Deutschstrasse 30. For the next few months, attendance again approached sixty persons, whereas only about forty had been attending services held in the homes of member families.[27]

Later in the war, Margarethe Dretke and her son Ulrich (“Ulli,” born 1938) were evacuated to a farm in Kannenberg. From there, she was required to leave her son for a month to dig antitank ditches near Driesen. As she explained, “The ditches were supposed to be four meters [thirteen feet] deep so that the tanks would fall into them. It happened differently than we expected; [the invaders] just drove past them.” Sister Dretke protested being absent from her son and was allowed to return to Kannenberg.

Ulli’s recollection of the time on the farm was that of a little boy. “I was so homesick. I never wanted to go to bed.” He loved the animals and even sneaked into their pens to sleep with them at night. He recalled spending one night with a huge bull that was fed on a fermented sugar beet substance (“it kept the animals drunk, and they slept better”). Ulli ate some of the same feed and later recalled that “when they got me out [of the pen] I felt pretty good.”[28] This incident apparently added to his father’s insistence that his wife and his son return to Stettin without delay.

When Sister Dretke returned to Stettin, she was again assigned to dig fortifications around the city. She tried hard to avoid the work, insisting that she had already done enough. “Brother Oppmann of the branch recommended that I do as I was told so [the government] would not take my child away. It was a great blessing, and I am still grateful today for his advice.”

In August 1944, Elli Polzin had the following distinct dream:

I dreamed of a large hall. . . . At the end of the hall, I saw my husband standing. He wore a white coat like he always did as a hairdresser. He was cutting somebody’s hair, and I was so excited to see him. I went over to him, but we were not allowed to show anybody that we knew each other. I offered him a glass of water, and our hands touched. We looked each other in the eyes, and that was a wonderful moment. The [other] people then told me that I had to leave again. It was so hard for me to leave him.

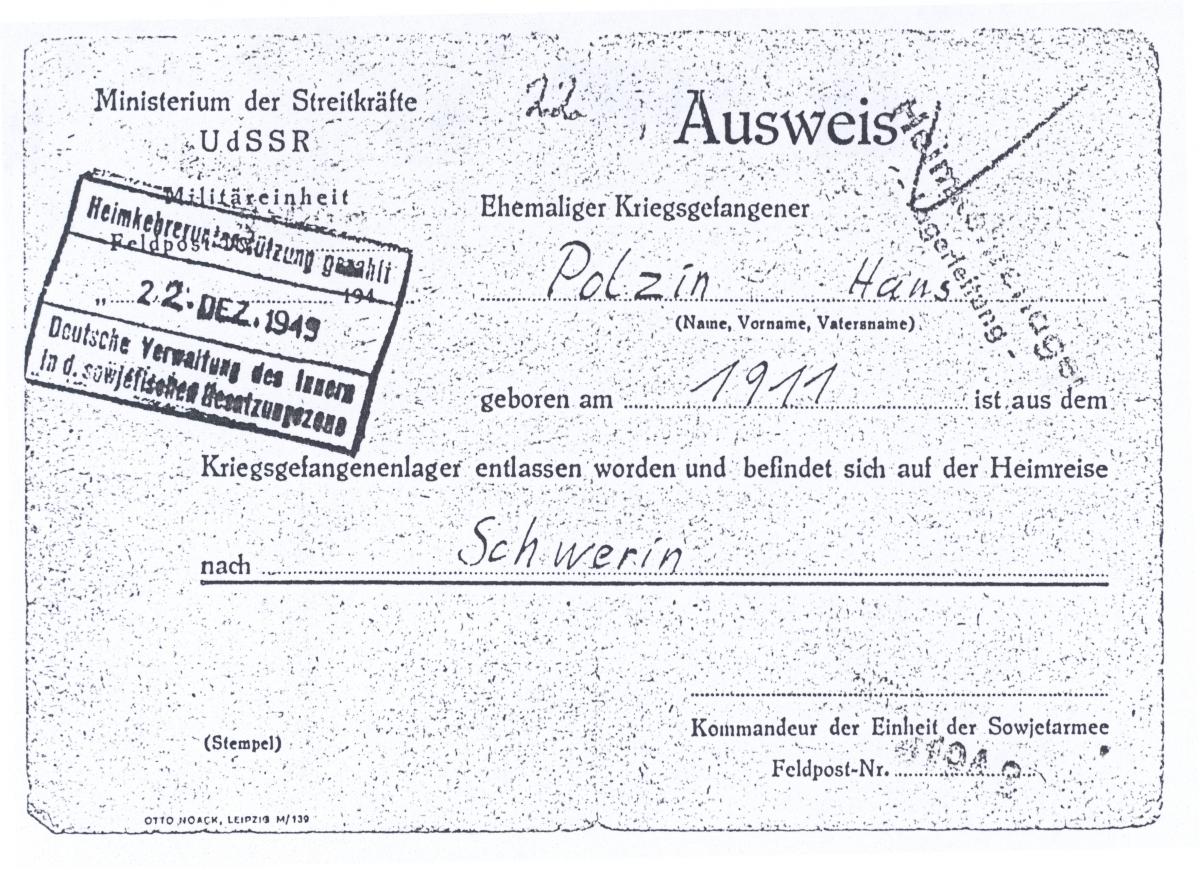

The next morning, the local Lutheran pastor came to inform Elli that her husband had been reported missing in action in Rumania. The pastor was sorry and explained that Hans might be dead. Her response was as follows: “I looked him in the eye and said that [Hans] was alive and that I knew it. I told him about the dream, and he said that it was not coincidental.” For the next three years, Elli did not know anything about her husband’s whereabouts.

The family of Otto and Margaretha Bork in 1943. Soldiers Alfred (left) and Paul were “missing in action” when the war ended—and still are. The parents never gave up hope that their sons would return someday (H. Bork)

The family of Otto and Margaretha Bork in 1943. Soldiers Alfred (left) and Paul were “missing in action” when the war ended—and still are. The parents never gave up hope that their sons would return someday (H. Bork)

A massive air raid hit Stettin on April 11, 1944. Former district president Dieter Berndt was killed at his workplace—an aircraft factory just outside of town.[29]

Johannes Zunkowski (serving at the time as the president of the Stargard Branch) worked at the same factory and was buried under the rubble of his building. For approximately sixteen hours, he waited to be rescued. According to his son Bernard, “The building just collapsed, and there was a pocket underneath, and he was able to breathe in there, but nobody knew he was under there. For some reason, one of the bombs didn’t go off [on impact], but exploded hours later and uncovered my father. So he came home. His hair turned white overnight.”[30]

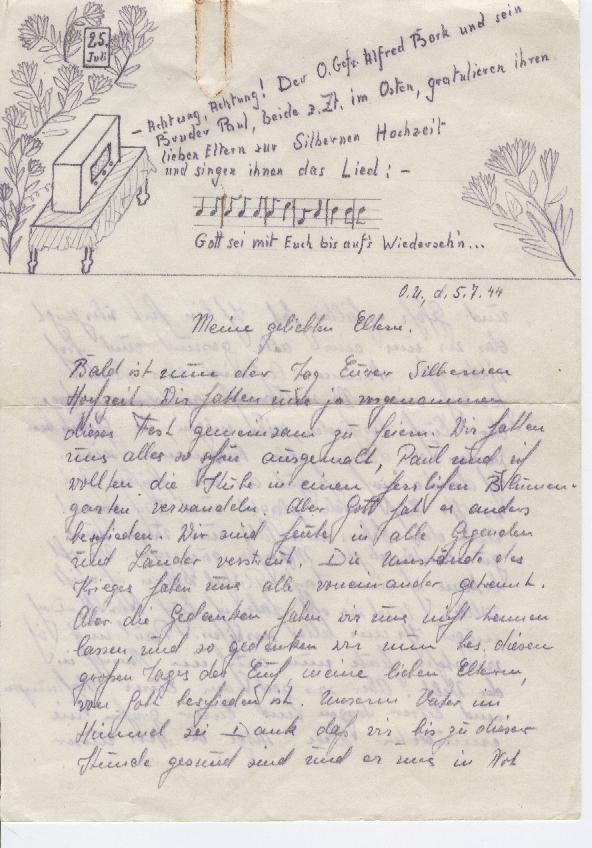

Alfred Bork wrote this letter to his parents in July 1944 on the occasion of their silver wedding anniversary. The illustration at the top is a reference to the bombastic national radio broadcasts of German victories. The music notes represent the hymn “God Be with You till We Meet Again” (H. Bork)

Alfred Bork wrote this letter to his parents in July 1944 on the occasion of their silver wedding anniversary. The illustration at the top is a reference to the bombastic national radio broadcasts of German victories. The music notes represent the hymn “God Be with You till We Meet Again” (H. Bork)

Bernard recalled the prologue to that devastating attack, when he and his friends were playing cowboys and Indians:

There was an open field where we used to build teepees. . . . All of a sudden I heard this rumbling, and I looked up in the sky, and the sky was just covered with airplanes. It was just covered. And you could see all the bomb doors were open and the fighter planes. And there was a big fight because we had an air base in Stettin, a big air base. So there was a big fight above us, and shrapnel was flying everywhere. That day, my dad was buried alive.

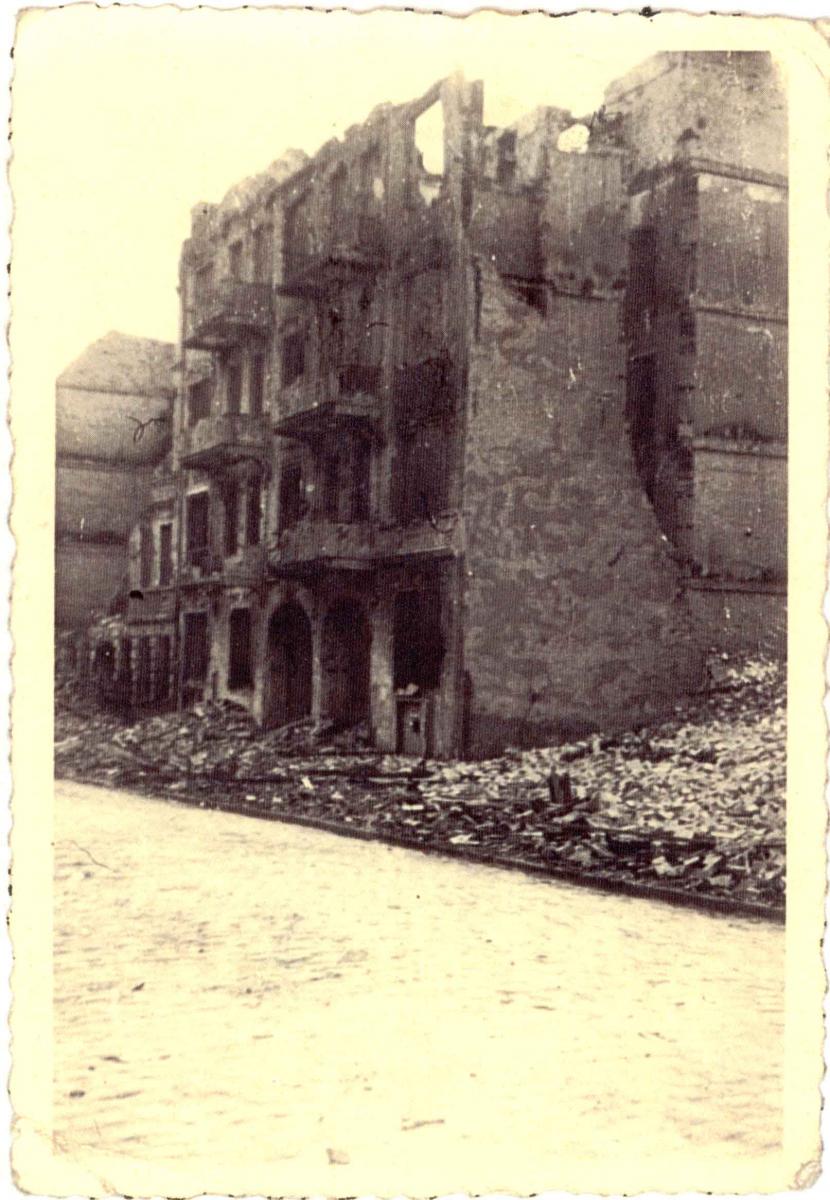

On August 30, 1944, Stettin was visited with the full fury of the war, as enemy airplanes reduced large sections of the city to rubble. Anni Bauer had joined her neighbors in the basement of a large apartment house that suffered a direct hit. The terror she experienced is evident from the story she wrote:

The walls were cracking and caving in, but the worst was still to come. . . . For a moment I thought my life was over because I had difficulty breathing with the pressure that was on my lungs. . . . One thing I shall never forget: seeing all the people crowding together in the shape of a great “ball” . . . all of them crying to God for help. . . . I had only one thought in mind, to get out of the terrible fire . . . Another bomb shook our ruins, and I cried to the Lord to take my life now and not let me be smothered by rubble or be burned alive.[31]

Helmut Plath conducted the funeral of former district president Erich Berndt in 1944 (D. Berndt)

Helmut Plath conducted the funeral of former district president Erich Berndt in 1944 (D. Berndt)

Anni drenched herself with water from the barrel in the basement, then raced through the flames upstairs into the street. Then she ran to the park at Blücher Square, assuming that the park would be free of fire and smoke. She was wrong because phosphorus bombs had spread fire everywhere. “The trees were burning, bushes and benches were in flames. The heat was so tremendous and the smoke would have killed us if it hadn’t been for the underground shelter.” Anni saw several people burning alive in the streets. “It was the greatest horror,” she would recall in her memoirs.[32]

The apartment building in which the family of Otto and Margarethe Bork lived in Stettin was also destroyed in 1944, and the family was instructed to come back long enough to see if they could salvage anything important from the ruins. Young Hellmut (born 1933) recalled hearing from a neighbor that his older brother, Paul, had been reported killed in the building during the bombing. There was even an announcement in the newspaper to that effect, but the family had since received letters from Paul in the Soviet Union. They knew that he was still alive.[33] This was, however, not the case for long. In September 1944, the Borks received a letter from Paul’s company commander indicating that their son’s unit had been surrounded during a recent battle. He had not been seen since and was believed to be a POW.

Anni Bauer was nearly buried alive in the basement of this building (A. Bauer Schulz)

Anni Bauer was nearly buried alive in the basement of this building (A. Bauer Schulz)

In the fall of 1944, the Red Army was approaching Christenenberg, so Gerda Stenz Winter took her son back to Stettin. Her husband was temporarily in Stralsund for more navy training and encouraged her to join him there. Unfortunately, the trip was very difficult because refugees were overloading all trains headed west. Gerda’s father went with her to the railroad station and successfully used cigarettes to bribe the conductor to take his daughter and his grandson onto the train—along with their baby stroller. At one point on the journey, she left the stroller in a place where it easily could have been stolen but came back to find it still standing there. In Stralsund, she found her husband, and they were successful in renting a room to stay in. It was cold, so Heinz went out to a local park to gather enough wood to keep a small fire going. A few days later, they parted as Heinz returned to duty. They agreed to meet after the war in Varel in the western province of Oldenburg because they believed that it would not be safe to be in any region where the Red Army was likely to be the occupation force. It was February 1945.

When Heinz Winter left Stralsund, he was no longer bound for the sea. He had responded to a call for more ground troops and had transferred voluntarily to the army, as he explained:

They said that if I volunteered for the infantry, I could choose my unit and area of service. I wanted to help defend Stettin, but they sent me to Czechoslovakia instead. . . . I was trained as a forward observer [for artillery], sitting out there in front of the infantry. [Forward observers] were all lieutenants, and losses among them were very high.

Back in Stettin in 1944, the Dammaschke family moved into some barracks outside of town. From there, Sieglinde’s mother went to church now and then by herself. She dressed the children, prayed with them, and then made the long trek into town to join with other branch members for meetings. Neighbors were unhappy with this young mother for leaving her children alone in the camp, but she did nevertheless, explaining, “They’ll say their prayers, and they’ll be safe.”

During the fall of 1944, Germans from the eastern provinces of the Reich began to evacuate their homes as Soviet soldiers moved toward the Reich. Johann Zunkowski’s family lived on the outskirts of Stettin, and young Bernard observed the stream of refugees moving westward:

Our little home was maybe a couple of blocks away from the autobahn, and you could see the people. Day and night they were walking down the road trying to get away from Russian troops. At night, a lot of times, they used to come in our backyard and settle down for the night. Sometimes we used to help them out as much as we could. We’d supply the food, and we’d find shelters for the horses.

The Zunkowski family eventually joined the throngs of refugees in January 1945. The beginning of their flight was not encouraging, as explained by young Bernard:

We left at one o’clock in the morning, and there was about a foot of snow on the ground and most of the neighbors had already left. We put my grandma on top of the wagon and just a couple of suitcases. My dad and I were pulling. My mom was pushing. My brother [Wilford] was drafted [and gone]. So that’s how we left. Then after we were going along the side of the road, they came down with the fighter planes and just strafed the roads. Somehow, all of a sudden, a truck came by and stopped, and two soldiers got out. They lifted our little wagon inside and us, and they drove all night long.

In January 1945, the Red Army moved through Gielow, and Elli Polzin decided to return to Finkenwalde. The war was not yet over, and the Soviets occupied the entire area, so she was instructed to leave again. This time she went to the island of Rügen in the Baltic Sea, where conditions were relatively calm and safe. She lived there in a hotel with her children. There was no branch of the Church on the island, thus by the end of 1945, the mission leaders recommended that she move west to Schwerin, where refugees from the east had established a branch. It was there that her husband found them.

In early 1945, Anna Kopischke and her family left Stettin on a train heading west for Strasburg. Moving ahead of the advancing Red Army, they went through Neubrandenburg, where they were joined by Anna’s fiancé, Horst Röhl. He had been recuperating in a military hospital and accompanied them through Malchin and Wismar to a castle near Plüschow. From there, they crossed the border into the British Occupation Zone and then settled in the town of Elmshorn. Writing to an address she found in an old issue of Der Stern, Anna established contact with the Altona Branch in Hamburg, and they began to attend Church meetings again.

The apartment house in which the Dretke family lived survived the war undamaged, but a dud once landed in the henhouse just ten feet behind the building. As the invaders approached the city, Waffen-SS troops set up defensive positions in the apartment house. Thanks to them, the family had enough food to eat when things got very scarce. The soldiers also promised to help them escape the city when the Soviets got too close. During those last months, Brother Dretke was often required to stay overnight in the factory where he was employed.

When the time came to leave Stettin, Margarethe Dretke took her son, Ulli, and a few important items, as she recalled: “a pan with oatmeal, my papers, and a bottle of water.” The train was already full, and refugees from eastern Germany were trying to board with grains, animals, and other items for which there simply was no room. “People dragged my son and me into the train through the windows. In that train, some of the wounded soldiers were dying, while others sang.” Margarethe and Ulrich rode the train west as far as the port city of Lübeck and found a place to stay in a chicken coop.

Branch president Kurt E. Lehmann made his last entry in the Stettin Branch minutes on March 25:

Six members gathered today. They walked from the meetinghouse to the home of Brother and Sister Pautsch at Mackensenstrasse 22. There they had a short discussion under the leadership of Brother Johannes Zdunkowski. This was the last meeting. Everybody was to evacuate Stettin because the city was under artillery barrage. The members have been scattered in all directions. Some have been evacuated to [the province of] Mecklenburg. This is the end of the Stettin Branch.

[signed] Branch President Kurt E. Lehmann.[34]

In April 1945, Otto Bork instructed his wife, Margarethe, to take the three children and work her way toward the advancing American Army (away from the Soviets). The four of them headed north and west and soon found themselves in the company of German soldiers whose task was to destroy every bridge they crossed on the way west. This would prevent or at least delay the advance of the Soviet Army. Each time the Borks crossed a river, the soldiers dynamited the bridge behind them. One night, the soldiers left while the Borks were asleep, and they were awakened by a tremendous explosion. The soldiers had blown up the next bridge, leaving the Borks stranded on the east side. That day, they were overtaken by the advancing Soviets, who ordered them to return to Demmin.

As they retraced their route to Demmin, Hellmut Bork found a nice bicycle, but the chain was gone, so he pushed it along as a luggage carrier. A Russian solder went by and demanded that Hellmut trade for the older bicycle the Russian had. Hellmut tried to make the man understand that his newer bicycle was not functional, whereas the older one the soldier had was in good condition. The trade took place anyway. Hellmut’s gain was short-lived, however. When the arrived in Demmin, he had to surrender his bicycle to the conquerors, as did everybody else in town.

After hearing of her husband’s death in the air raid the day after Easter of 1944, Erika Berndt took her two children back to Stettin, where their home still stood. In the spring of 1945, her father joined them in the trek west, their Bollerwagen loaded with their most valued possessions. By the time they arrived in Neubrandenburg, the advancing Soviet Army had caught up with them. They saw enemy soldiers for the first time while hiding in the basement of an aunt. The conquerors ordered them to return to Stettin.[35]

Following the destruction of their home, Margarete Kuehne moved with her daughters and Waltraut’s grandparents to Anklam (fifty miles to the northwest). They were there when the Soviets arrived in April 1945. The first night, the local residents were ordered into the hospital across the street, while the invaders searched for German soldiers. Then they were sent back to their homes and were terrorized by the invaders soon thereafter. According to Waltraut:

[The Russians] came every night and in every house to steal . . . They came in, and [one of them] took my [little] sister from my mother’s arms. And they all stood there with machine guns, we thought that was the end. But my mom ran to him and grabbed my sister from him. We were so scared, and they were so drunk. They were laughing when they left the house. That’s the first bad experience that I had.

The American army entered Czechoslovakia in April 1945, and Heinz Winter’s unit confronted the invaders west of the city of Plzen. Heinz later described the successful German attack, planned for a hilly location where the road was quite narrow: “We just had bazookas [Panzerfaust], but we shot the first tank, and the whole [column] stopped. Then they were practically at our mercy.” Later, the Germans fought the invaders near an orphanage where the Americans had established their headquarters, again winning the day. “We took forty [Americans] prisoner, some badly wounded. Since we didn’t have any facilities, we couldn’t help them. We put them on one of their jeeps, put a Red Cross flag up, and drove to the next little town.”

In an odd situation, Heinz and his comrades negotiated with the Americans and won a very important concession: the German soldiers were to be given release papers to go home, meaning that they would not become POWs. Within two weeks after the war ended on May 8, Heinz was on his way to Germany. He knew that his father was working in a salt mine near Nordhausen, so he went there, walking the 180-mile route.

Gerda Winter was to go to Varel in western Germany, but decided instead to join her parents-in-law in Nordhausen in central Germany. She sought the security of family and moved in with a Schneider family in the town of Kleinberndten, where her mother-in-law was staying. It was in Kleinberndten that Gerda experienced the end of the war—the arrival of the American army. Under the command of a Jewish officer, the Americans moved into the Schneider home and evicted the residents. Gerda later wrote what they found when the Americans left: “The whole house was in chaos, they trampled on the baby’s feather bed, ripped open every glass of fruit in the house, took all the cooking pots and urinated in them. My two beautiful rings were gone, which I [had] left on the counter.”[36]

Willi Dretke at work at his lathe (H. Dretke)

Willi Dretke at work at his lathe (H. Dretke)

Just before Stettin was conquered by the Red Army, Willi Dretke and his colleagues loaded their factory’s machinery onto flatbed railroad cars and transported it west to Lübeck. Willi was required to ride on the open freight car with his machine and contracted a lung ailment along the way. He was eventually able to join his family in Lübeck but did not recover from the malady. Without proper medication, he died there on August 25, 1945.

The Dretke family had left almost everything they owned in Stettin. As Margarethe explained:

When we left Stettin, we . . . thought that we would just go back when the war was over. We left our apartment clean so we would find it proper and nice when we returned. We could have gone back to Poland, but we didn’t want to be in a country that wasn’t ours anymore. [The Polish] also didn’t want us to go back anymore.

After living in her grandmother’s home in Neubrandenburg for a short time, Ruth Krakow’s family moved in with the Huppel family across town on Demminer Strasse, where they lived in cramped quarters. Ruth later described the conditions in these words:

It was an apartment in which the owner had one room; another family from Tilsit lived in the other with their four children, and my mother and I lived in the last room. We all had to share the kitchen, and we often had arguments about it. Because we still had to heat with coal, we had to have schedules of who would cook when. We did not have much, and if somebody had a piece of meat still on the stove, that person had to be careful.

When the conquerors entered Neubrandenburg in 1945, Ruth Krakow and her mother were fortunate to escape harm. “My father had taken a couch and built a hiding place for us so nobody could see us. . . . The Russians were not nice to adults, but they never did anything to children. They gave [us] bread.”

Sieglinde Dammaschke left Stettin with her mother and siblings, bound for Hamburg with their possessions loaded in a baby buggy and a small wagon. Along the way they were persuaded to travel to Erfurt instead (225 miles to the southwest). Living there in a small attic space, they experienced the arrival of the American army in April. Two months later, the Americans moved out, and the Soviets came into Erfurt, which upset many of the locals. Sieglinde’s mother decided to leave while she had the chance and traveled back to Hamburg. Her husband joined the family there after being released from a POW camp.

By the spring of 1945, Alfred Bork had not seen his parents for nearly a year, but a sister of the branch later told of seeing him in Stettin in early May. She was watching as hundreds of German POWs were being marched through the city by their Soviet captors. She thought she recognized Alfred among them and called out to him. Just at the moment when he turned to look at her, she was knocked down by a guard. By the time she got back to her feet, he was too far down the street to see again.

When the Red Army approached the prison camp where Otto Bork was in command, his two comrades took to the hills. Brother Bork stayed and handed over the camp to a Soviet officer in a jeep. Just when it looked like Otto would be killed, inmates came forward to testify that he had treated them very correctly under the circumstances. Because of this, he was given a written statement to allow him safe passage back to Demmin. He set out, carrying a small briefcase full of invaluable family documents, such as his genealogical papers, family photographs, and Alfred’s diaries (he had kept this suitcase with him since the war began). Along the way, he was confronted by a squad of Red Army soldiers who proceeded to rough him up. They opened the suitcase and threw his papers all over the road. Despite his agony about losing those treasures, he remembered the certificate in his pocket and quickly produced it in his defense. The squad leader was shocked to read it and immediately apologized for the mistake. The soldiers gathered up the papers and returned them to Brother Bork, asking him to not report their misconduct. He was relieved to continue his walk to Demmin, where he joined his family about two weeks after they had returned from their abortive flight west.

Shortly after the war ended—Georg Kuehne took his family back toward Stettin. With a small Bollerwagen, they walked the entire distance (fifty miles) from Anklam. Because there was no place for them to stay in Stettin, they continued on to the home of Waltraut’s grandparents in a nearby village. The home had already been confiscated by a Polish family, so the Kuehne party moved on to a refugee camp about one-half hour away.

In late May 1945, Heinz Winter showed up in Kleinbernten to be with his family. Gerda (who had not heard from him since February) later wrote of their reunion: “Nobody can believe how I felt when I saw my husband standing in front of me alive after the most horrible war.” Then Gerda and her son both contracted what was called the Russische Krätze—a frightening and painful skin condition. Fortunately, they were treated in a local hospital. Grandpa Winter also gave them a blessing, and they were healed in two weeks; the doctors called them “miracle people.” The Winters moved onto a farm, where both parents worked for room and board. The work was extremely hard for Gerda, but she realized how blessed they were that they had employment and food while others were dying of hunger. For the next two years, Heinz had to be on the lookout for Russian soldiers who were often hunting for former German soldiers, especially those with technical skills. Many were sent to the Soviet Union as involuntary laborers. Heinz escaped that fate.[37]

The Zunkowskis were fortunate to get to Güstrow, north of Berlin, where there was some degree of safety. However, in the summer of 1945, they were ordered to return to Stettin, but those orders were countermanded and they were stopped at the Oder River. Turning back westward, they made their way to Berlin and were taken in at the mission home on Rathenowerstrasse. In September, Wilford (only fifteen and a Soviet POW at the time) was able to escape and join his family in Berlin. They eventually moved to the suburb of Charlottenburg, where Brother Zunkowski became the president of a new branch.

Looking back on the war years, Sister Dretke summarized her feelings:

I had a very strong testimony of the gospel during the war. There was no doubt about anything even though the war situation was difficult. There was nothing that could weaken my testimony. Difficult things only made it stronger. My husband’s testimony stayed strong in the same way.

The nightmare that began for the Kuehne family in Anklam continued in Poland. On December 2, 1945, Polish soldiers broke into the home and subjected the family to heinous abuse. The next day, Waltraut found her girlfriend dead. She had been shot in the stomach by the soldiers and had then jumped out of a window. Waltraut’s Grandmother Schoening had been quite ill and passed away that same night. The next morning, a wagon came by and several bodies were loaded on and taken away. By this time, it was clear that there was no reason for the Kuehne family to remain in the territory that had been ceded to Poland, so they applied for permission to head west into Germany.[38] By April 1946, they found a new home in Schleswig-Holstein in the British Occupation Zone.

When asked how she maintained a testimony of the gospel during those hard times, Waltraut Kuehne made these comments:

[My testimony] wasn’t there once in a while. It was gone once in a while. It was gone that time in Anklam. It was gone that time near Stettin. That I night I said there couldn’t be a God. Little did I know. But that’s the way I felt. But the thing that kept me going was my dad. It didn’t matter how bad things got, my dad never doubted.

Erika Berndt survived the first post-war months in her home on the outskirts of Stettin. In February of 1946, she was evicted from her home and headed west with her children. She arrived a few weeks later in northwest Germany near the town of Bad Segeberg. According to her son, Dieter (born 1938), “my mother immediately prayed that we could find a branch of the Church nearby.” After sleeping on straw in a barn for six weeks, the Berndts finally found a place to live and life began again.

The certificate of release of Hans Polzin as a POW in Russia

The certificate of release of Hans Polzin as a POW in Russia

One day in December 1949, the Schwerin radio station named Hans Polzin as one of the POWs scheduled to arrive from the Soviet Union that day. Elli and her children waited at the railroad station for an hour in anticipation of his arrival. As she later recalled:

That hour for us seemed longer than any other hour we ever went through. When the train came, I saw him getting off of the last car. I recognized him, but he looked different. At first, I asked myself if it was really him. We went home together but we could really not believe it for the longest time. We had to get used to each other again. The children stared at their father often, not believing that he was home. . . . The first few weeks he was home, it was not very easy. . . . He had changed; he had gone through so much.

By the summer of 1946, the many surviving members of the Stettin Branch had left the city voluntarily or when compelled by the conquerors. The branch disappeared into history.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Stettin Branch did not survive World War II:

Erich Hermann Wilhelm Berndt b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 25 Jul 1907; son of Hermann Gustav Berndt and Marie Magdalene Koch; bp. 8 Sep 1923; m. Stettin 9 Jan 1937, Erika Edith Gerda Boldt; 2 children; k. air raid Arnimswalde, Pommern, Preussen 11 Apr 1944 (D. Berndt; AF; IGI)

Fritz Otto Karl Berndt b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 15 Feb 1910; son of Hermann Gustav Berndt and Marie Magdalene Koch; bp. 8 Sep 1923; m. Stettin 12 Apr 1937, Dora Gertrud Luise Geschke; noncommissioned officer; k. in battle Bol.-Orahewo, Belarus 5 Jul 1944 (D. Berndt; www.volksbund.de; AF; IGI)

Fritz Berndt

Fritz Berndt

Johanne Elfriede Boenke b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 7 Oct 1904; dau. of Wilhelm Boenke and Klara Mueller; k. air raid Stettin Feb 1945 (CHL CR 375 8 2458, 1378)

Otto Rudolf Böhnke b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 6 May 1912; son of Wilhelm Adolf Böhnke and Anna Therese Pauline Schugk; bp. 5 Jun 1920; ord. priest; d. Stettin 11 or 12 Feb 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 20, 18 May 1941, p. 80; Sonntagsgruss, no. 11, 16 Mar 1941, 43)

Guenter Karl Hermann Boldt b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 9 Nov 1920; son of Karl August Friedrich Boldt and Anna Ida Marie Schuenke; k. in battle 19 Jun 1943 (D. Berndt; AF; IGI)

Günter Boldt

Günter Boldt

Alfred Karl Otto Bork b. Lötzen, Ostpreuβen, Preussen 18 Jan 1920; son of Otto Franz Paul Bork and Margarethe Emilie Kuehn; bp. 14 Apr 1928; conf. 14 Apr 1928; ord. deacon 5 Jul 1936; ord. teacher 2 Apr 1939; MIA Russia 2 Apr 1945 (H. Bork; IGI)

Paul Walter Artur Bork b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 7 Jan 1924; son of Otto Franz Paul Bork and Margarethe Emilie Kuehn; bp. 4 Jun 1932; conf. 5 June 1932; ord. deacon 2 Apr 1939; ord. teacher 25 Oct 1942; corporal; MIA Brody, Galicia, Russia 22 Jul or Sep 1944 (H. Bork; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Hulda Marie Mathilde Schmalofoski b. Breitenwerder, Friedeberg, Neumark Brandenburg, Preussen 10 Mar 1879; dau. of Friedrich Wilhelm Schmalofski and Wilhelmine Karoline Viedt; bp. 4 Aug 1924; m. 1 Sep 1906, Johann Gustav Franz Borrmann; d. malnutrition as refugee Güstrow-Schliefenberg, Mecklenburg Sep 1945 (Zdunkowski, IGI)

Franz Johannes Albert Brüsch b. Pommerensdorf, Pommern, Preussen 10 Mar 1876; son of Johann Christian Michael Brüsch and Friederike Juliana Neumann; bp. 30 May 1924; m. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 28 May 1902, Minna Marie Amalie Kirchoff; 4 children; d. heart disease Stettin 1 Nov 1939 (Stern 1 Jan 1940, no. 1, 15; IGI)

Gustav Buyny b. Schwente, Westpreussen, Preussen 13 Aug 1872; son of August Buyny and Christine Holzer; bp. Schwendain, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 2 Jul 1901; m. Auguste Boldt; d. Stettin 8 Jun 1942 (CHL LR 12728 11, 57; IGI)

Heinz Dieckmann b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 2 Oct 1919; son of Albert Emil Dieckmann and Johanna Ebert; bp.; ord. deacon; MIA Russia Sep 1944 (I. Dieckmann Whitlock)

Heinrich Wilhelm Karl Diekmann b. Welstorf, Lippe 28 Apr 1864; son of Christian Heinrich Diekmann and Dorothea Catharina Johanna Haak; d. 14 Apr 1944 (IGI)

Max Dretke b. Schmiedeberg, Posen, Preussen 27 Dec 1918; son of Wilhelm Dretke and Emilie Riehm; bp. 2 Dec 1937; m. 1 Feb 1941; MIA Orel, Russia 17 Mar 1943 (court ruling; H. Dretke)

Willi Artur Herman Dretke b. Wongrowitz, Posen, Preussen 17 Jul 1912; son of Wilhelm Dretke and Emilie Riehm; bp. 14 Apr 1928; m. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 30 Mar 1935; d. pneumonia Lübeck 25 Aug 1945 (H. Dretke; IGI)

August Friedrich Ferdinand Ebert b. Schillersdorf, Randow, Pommern, Preussen 25 Nov 1865; son of Carl Friedrich Ferdinand Ebert and Henriette Karoline Friederike Winkelmann; bp. 24 Mar 1901; ord. elder; m. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 27 Dec 1892, Hedwig Johanne Karoline Suhr; 9 children; d. old age Stettin 25 Dec 1944 (I. Dieckmann Whitlock; FHL Microfilm 25759, 1935 Census; IGI)

Herbert Karl Arthur Habedank Memel, Ostpreussen, Preussen 23 Mar 1923; son of Friedrich Carl Habedank and Anna Martha Berscheit; k. in battle Eastern Front 22 Oct 1943 (CHL LR 12728 11, 86; IGI)

Auguste Matilda Harwald b. Klein Zappeln, Schwetz, Westpreussen, Preussen 8 Feb 1870 or 1871; dau of Gustav Harwald and Henriette Schmeichel; bp. 26 Dec 1908; m. Taschau, Jeschowa Westpreussen, Preussen 31 Mar 1904, Gustav Adolph Kuhn; 3 children; m. Gustav Krebs; d. Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 15 Aug 1943 (FHL Microfilm 271381, 1925/

Elisabeth Matilde Hennig b. Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 21 or 22 Oct 1883; dau. of Friedrich Wilhelm Hennig and Bertha Anna Ernestine Korth; k. air raid 30 Aug 1944 (CHL LR 12728 11, 78; FHL Microfilm 162781, 1925/

Erwin Karl Otto Hönig b. Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 17 May 1923; son of August Hermann Hönig and Agnes Helene Emilie Burtelt; bp. 1932; rifleman; k. in battle by Tureni, Romania 21 or 29 Sep 1944; bur. Cluj, Romania (CHL LR 12728 11, 78; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Hermann Gustav Jahn b. Landsberg/

Ernst Robert Otto Lehmann b. Pommerensdorf, Pommern, Preussen 12 Sep 1872; son of Albert Julius Alexander Lehmann and Marie Luise Koeckeritz; bp. 30 Mar 1907; m. Pommerensdorf 3 Aug 1895, Mathilde Pauline Alwine Loehn; d. heart failure Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 2 Sep 1939 (Stern, no. 21, 1 Nov. 1939, 340)

Karl Willi Rudi Lehmann b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 16 Oct 1920; son of Karl Ernst Otto Lehmann and Hertha Bertha Elfriede Appelgruen; bp. 26 Jun 1929; soldier; k. in battle 28 Jul 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 28, 21 Sep 1941, 112)

Anna Maria Elisabeth Oehlke b. Schwenz, Cammin, Pommern, Preussen 20 Oct 1873; dau. of Johann Friedrich Oehlke and Johanna Friedricke Henriette Manthey; bp. 31 May or 1 Jun 1924; m. Lange; d. Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 14 Feb 1944 (CHL LR 12728 11, 91; IGI)

Julius Karl August Schmidt b. Seeligsfelde, Pommern, Preussen 15 Feb 1871; son of Friedrich Wilhelm Schmidt and Karoline Friederike Wilhelmine Dummer; bp. 14 May 1910; m. Seeligsfelde 16 May 1905, Bertha Anna Augusta Reeck; 3 children; d. old age Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 11 Dec 1943; bur. Stettin 13 Dec 1943 (CHL LR 12728 11, 88; IGI)

Hedwig Johanne Karoline Suhr b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 12 Jul 1874; bp. 24 Mar 1901; dau. of Friedrich August Johann Suhr and Luise Wilhelmine Sophie Suhr; m. Stettin 27 Dec 1892, August Friedrich Ferdinand Ebert; 9 children; d. heart attack Wismar, Mecklenburg-Schwerin 4 Apr 1945 (I. Dieckmann Whitlock; FHL Microfilm 25759, 1935 Census; IGI; AF; PRF)

Gerhard Alfred Weigand b. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern. Preussen 19 Jul 1913; son of Philipp Weigand and Meta Katilius; missing as of 1948 (CHL CR 375 8 2458, 824; CHL 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 824–25)

Franz Rudolf Wichmann b. Deutsch Wilten, Ostpreussen, Preussen 31 Jan 1862; son of Gottlieb Wichmann and Julianne Charlotte Schulz; bp. 29 Nov 1896; ord. elder; m. Stettin, Stettin, Pommern, Preussen 14 Aug 1890, Marie Regine Helene Garbrecht; 8 children; d. Stettin 4 or 8 Feb 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 11, 16 Mar 1941, 43; IGI)

Wilhelmine Johanna Sophie Günther b. Anklam, Pommern, Preussen 30 Mar 1866; dau. of Friedrich Günther and Wilhelmine Masch; bp. 14 May 1927; k. air raid 30 Aug 1944 (CHL LR 12728 11, 78; IGI)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Elli Martha Marie Zechert Polzin, interview by the author in German, Schwerin, Germany, August 17, 2006; unless otherwise noted, German summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[3] Margarethe Boehme Dretke Schmidt, interview by the author in German, Salt Lake City, July 12, 2007.

[4] Heinz Winter, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, April 13, 2006.

[5] Dieter Berndt, interview by the author in German, Berlin, Germany, August 20, 2006.

[6] Ruth Krakow Meyer, interview by Anne Regina Leonhardt in German, Neubrandenburg, Germany, October 16, 2007; unless otherwise noted, transcript or audio version of the interview is in author’s collection.

[7] Waltraut Kuehne Dretke, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, February 2, 2007.

[8] Alfred Bork, diary, July 30, 1939; private collection; trans. the author.

[9] Ibid., October 19, 1941 and April 5, 1942.

[10] Gerda Stenz Winter, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, April 13, 2006.

[11] Stettin Branch, Meeting Minutes, 1940–1943, LR 12728 11, Church History Library; trans. the author.

[12] Alfred Bork, diary, June 22, 1941.

[13] Ibid., July 24, 1941–December 3, 1941.

[14] Ibid., June 21, 1942.

[15] Gerda H. Winter, “My Life Story” (unpublished history), 4; private collection.

[16] This was most probably a priesthood meeting because only men were in attendance and no sacrament service took place. Heinz was a teacher in the Aaronic Priesthood throughout the war.

[17] Anna Kopischke Roehl, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, March 28, 2008.

[18], For a description of the preparations made by civil defense authorities in large cities, see the introduction.

[19] Sieglinde Dammaschke Zwick, interview by Rachel Gale, Salt Lake City, June 29, 2007.

[20] Under a program called Kinderlandverschickung, entire classes of schoolchildren (usually ages ten to fourteen) were evacuated from large cities and sent with their teachers or Jungvolk leaders to vacation areas where hotels stood empty. This is most likely the situation where Waltraut worked.

[21] Winter, “My Life Story,” 5.

[22] Anni Bauer Schulz, autobiography (unpublished), 73; private collection.

[23] Thea Bork Gierschke, interview by Jennifer Heckmann in German, Stuttgart, Germany, August 18, 2006.

[24] Stettin Branch, meeting minutes, April 20–21, 1943, 78.

[25] Ruth Bork Rügner, interview by Jennifer Heckmann in German, Stuttgart, Germany, August 18, 2006.

[26] Very common are stories regarding people in German cities who were too tired to go downstairs during alarms or who simply assumed that the bombs would not strike their neighborhood.

[27] Stettin Branch, meeting minutes, 87.

[28] Hans Ulrich Dretke, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, February 2, 2007.

[29] See the details of the tragedy in the Stettin District chapter.

[30] Bernard Zunkowski, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, April 24, 2008.

[31] Anni Bauer Schulz, autobiography, 78.

[32] Ibid., 79.

[33] Hellmut Bork, interview by the author, Kearns, Utah, January 20, 2006.

[34] Stettin Branch, general minutes, 118; meeting minutes, 1940–1943, 118.

[35] Dieter Berndt, interview by the author in German, Berlin, Germany, August 20, 2006.

[36] Winter, “My Life Story,” 7.

[37] Winter, “My Life Story,” 7–8.

[38] The modern Polish name for the city is Szczecin.