Selbongen Branch, Königsberg District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 310-20.

A unique branch in many ways, the Selbongen Branch was situated in a very isolated part of East Prussia from its inception in the 1920s until its demise in the 1970s. The branch was founded in great part thanks to the gospel dedication and missionary spirit of one member, Friedrich Fischer. He was converted in Berlin in the 1920s and went home to Selbongen to share the gospel with his relatives and his friends. The branch grew so steadily that the Church decided that the Selbongen Branch needed its own meetinghouse. One was constructed there in just two months during the year 1929. As of the outbreak of World War II in 1939, this was the only meetinghouse owned by the Church in Germany or Austria.

| Selbongen Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 6 |

| Priests | 3 |

| Teachers | 8 |

| Deacons | 6 |

| Other Adult Males | 40 |

| Adult Females | 62 |

| Male Children | 17 |

| Female Children | 14 |

| Total | 156 |

The Selbongen branch was, in many aspects of the word, a family. From its beginnings among the extended Fischer family, it came to include members of the Krisch, Kruska, Mordas, Pilchoswki, Skrotzki, and Stank families. The branch had existed barely two decades when World War II ended, but by then many marriages had occurred among these families. The rate of activity among the members of the branch was also exceptionally high.

Emma Stank Krisch (born 1915) was one of the first members of the LDS Church in Selbongen. Later she described the meeting rooms inside their unique structure:

Inside was just a chapel, and we had one room and one classroom. When you came in, on the left side was the classroom and straight [ahead] was the chapel. And there was a stage, a platform at the back. There was no electricity in the building.[2]

Regarding the décor in the meetinghouse, Günther Skrotzki (born 1930) recalled the following: “On the right wall was a picture of Heber J. Grant, and on the left wall one could see the quotation ‘Who will go up to the mountain of the Lord? . . . He who hath clean hands and a pure heart,’ embroidered on a large banner. On the right side there was a pump organ below the picture of the prophet [Heber J. Grant].”[3]

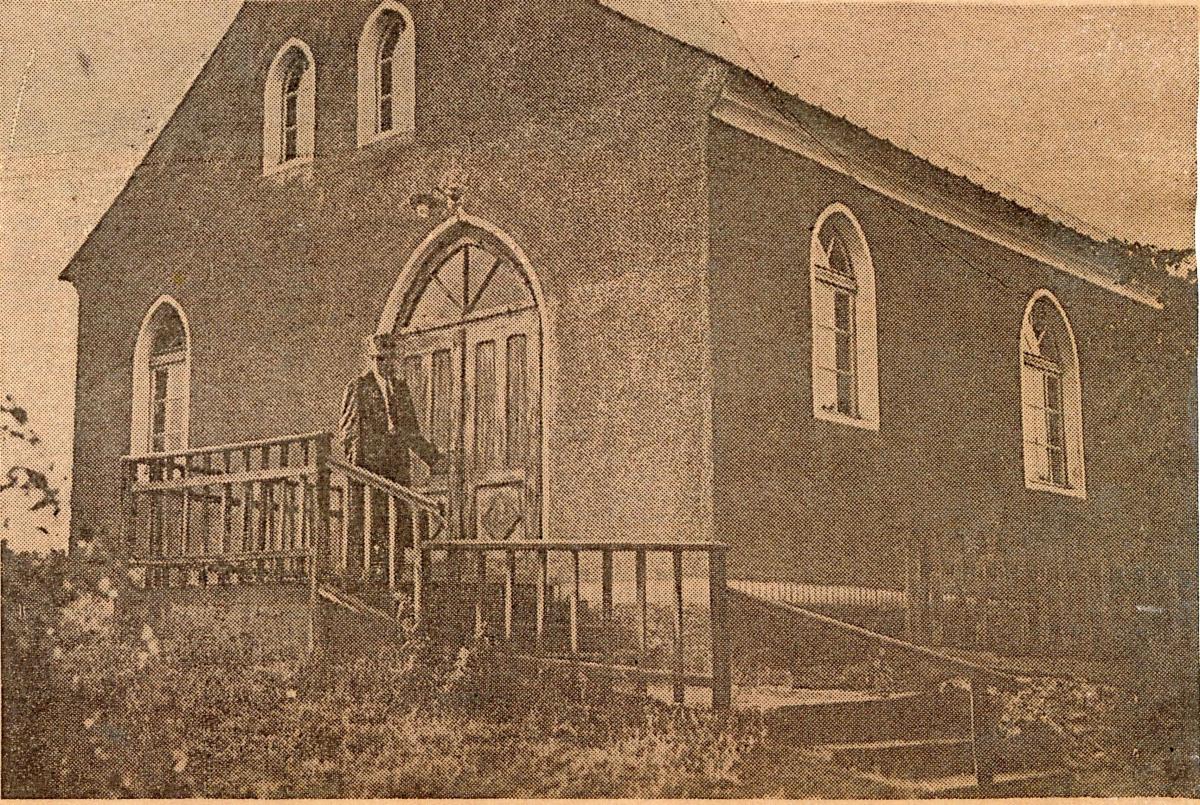

The East German Mission constructed this meeting house for the Selbongen Branch in 1929. This photograph was taken for the Deseret News in 1938. The building still stands.

The East German Mission constructed this meeting house for the Selbongen Branch in 1929. This photograph was taken for the Deseret News in 1938. The building still stands.

Emma’s daughter, Renate Krisch (born 1941), added these details: “There was no running water in the building and no restrooms, so we had to go next door to the Kruska home.”

Emma Stank Krisch recalled that many of the members of the Selbongen Branch did not live in the town of about six hundred inhabitants, but came from various small towns and farms in the vicinity. For this reason, the Sunday meetings were held consecutively in the morning.

For young Heinz Grühn (born 1934), “Christmas celebrations were always the most wonderful times.” He provided this description:

The Relief Society organized many get-togethers with food and a bazaar. We already started in July to practice for the Christmas program. Those programs lasted over two hours, and the entire village came to watch—the building was full of people, and there was no room left. These Christmas celebrations always happened on Christmas Eve. Sometimes, we had snow up to [four feet deep]. [4]

Heinz Grühn lived just across the street from the church building in Selbongen. His father, Otto, was a policeman who was not fit for military service, having burned his arm severely as a youth. Due to this condition, Otto was at home for nearly the entire duration of the war.

Renate Krisch provided an excellent description of the family home and domestic functions during the war and for several years thereafter:

It was a fairly new brick house, so it was nice. The only modern convenience it had was electricity . . . for lights. . . . There were no electrical appliances at all except for an electrical iron. There was no running water in the house. Drinking water and water for cooking, etc., was brought into the house from the well beside the house. . . . Water for washing clothes was “softer” from the lake. . . . Mother scrubbed all the clothes on a washboard with lye soap; there was no detergent. All the water had to be heated on the stove. . . . There was no bathroom in the house. . . . A steel tub that an adult could sit in was used for the weekly Saturday nights’ baths. The outhouse was in the back of the stable. . . . All the cooking was done on a “two burner” stove that was fueled with wood or coals. The big room was heated with a tile stove. It also served for baking bread.[5]

Emma’s husband, Wilhelm Krisch, was already in the Wehrmacht when World War II began. As a draftee, he was required to take his own motorcycle when he reported for duty. He participated in the campaign against Poland and then the campaign against France. By the time his first child, Renate, was born, it was 1941, and he was serving in Russia.

Shortly after the German invasion of the Soviet Union, Wilhelm Krisch and his comrades came under fire from enemy artillery. As he was running to join a group of seven of them in what appeared to be a good defensive position,

a soft, quiet voice called me by name, telling me that I should go back. When I heard the voice I started to run back. I got thirty to forty steps when I threw myself on the ground. Only a few seconds elapsed before a direct hit struck the group. . . . They were dead or wounded. The only thing that happened to me was marks on the stock of my rifle. . . . Our Heavenly Father warned me with the soft voice. I don’t know, perhaps I would have been dead also.[6]

At one point, Wilhelm was wounded in Russia and was sent to a hospital in Allenstein, about forty miles southwest of Selbongen. His wife was allowed to visit him there. Then it was back to war for Brother Krisch, who returned home on leave perhaps twice. He was not home when his two daughters were born. His last furlough was Christmas 1943, after which he was separated from his family for many years. According to his wife, Emma, “The loneliest days were Christmas and Mother’s Day. I felt sorry for my dear husband being gone for so long.”[7]

Regarding her husband’s experience in the army, Emma Stank Krisch later explained, “He did not get along well with the other soldiers. It was hard for him to live as a Latter-day Saint under those conditions. Once he had a Bible, but he really felt alone.” By the early summer of 1944, Wilhelm Krisch was near the Atlantic Coast in France, and he was captured by the Americans shortly after the D-day invasion in June 1944. He was allowed to write a card to his family so that they knew he was still alive.

Former Branch President Emil Skrotzki, father of six, was killed in 1942 (R. Krisch George)

Former Branch President Emil Skrotzki, father of six, was killed in 1942 (R. Krisch George)

Emil Skrotzki (born 1904) was a husband and father of six. He was no die-hard Nazi wishing to fight wars for the Führer; he just wanted to be home with his family. His son, Walter (born 1939), remembered that on his last visit home, this young father told his children, “I might not be coming back again.” Indeed, Emil was killed on the Eastern Front, and the Sonntagsgruss, the publication of the East German Mission in Berlin, announced his death on April 5, 1942.[8]

Günther Skrotzki, another one of Emil’s six children, remembered the experience as one of the worst things that can happen to a boy:

We were six children at home that waited for him to come back. I will never forget the day that we found out about my father [dying]. The mayor and a teacher came to our apartment, and I already heard my mother crying when I walked inside the house. Later, we received a little package with my father’s Bible and some other small things. One day, my mother and I visited a man who was in one room with my father. He told us that he would never forget the day when my father died. They had gotten a call to get ready because there was an alarm, and my father Emil was nowhere to be found. He went to look for my father, and he found him on his knees praying. He was the only one out of his group who died.

According to Günther, the branch conducted baptisms in three different small lakes near Selbongen. The water was not very cold when Günther was baptized in July 1939. Because the Church was well known and accepted in Selbongen, there was no need for secrecy on those occasions.

Annie Butschek (born 1927) remembered that even in a small town such as Selbongen, National Socialism was important to some of the citizens. For example, all of the programs for the youth were in place. “I was a part of the BDM and I liked it there. Our leader was a kindergarten teacher, and she practiced songs with us. There were no politics included at all.”[9]

In other instances, fanatics made sure that people toed the party line. Günther Skrotzki’s mother supported the foreign laborers and gave them clothing that her family no longer needed. Günther explained, “A farmer reported her to the local party officials. She was required to meet with the local political leader, and he explained that she was lucky that her husband [had] died in the war or she would have been taken to a [concentration] camp.”

Hitler Youth groups were known for their discipline and obedience, but there were exceptions. An odd incident happened in 1944 in the Jungvolk group to which Heinz Grühn belonged: “Some of the boys went to our leader’s home one night because he did not treat us well that day, and they told him what they thought of him and even hurt him on his way home. After that, he started to treat us better again.”

For the last year or so of the war, older men like branch president Alfred Kruska (who lived next to the church) and August Fischer were the only adult priesthood holders left to direct the activities of the branch. They were instrumental in looking after the many women and children who were trying to survive without their husbands or fathers.

Located far from any major city, Selbongen was spared the constant air raids and false alarms. Life was very calm there until the fall of 1944, when the Soviet Army set foot on German soil for the first time. Edith Mordas recalled living with her widowed mother and five siblings “in a beautiful house by a lake . . . a dream world” that included eight acres of land, a few chickens, and several pigs. Her grandmother also lived in the home and tried to calm their fears about the invading Russians: “The Russians are human beings, too,” she said.[10]

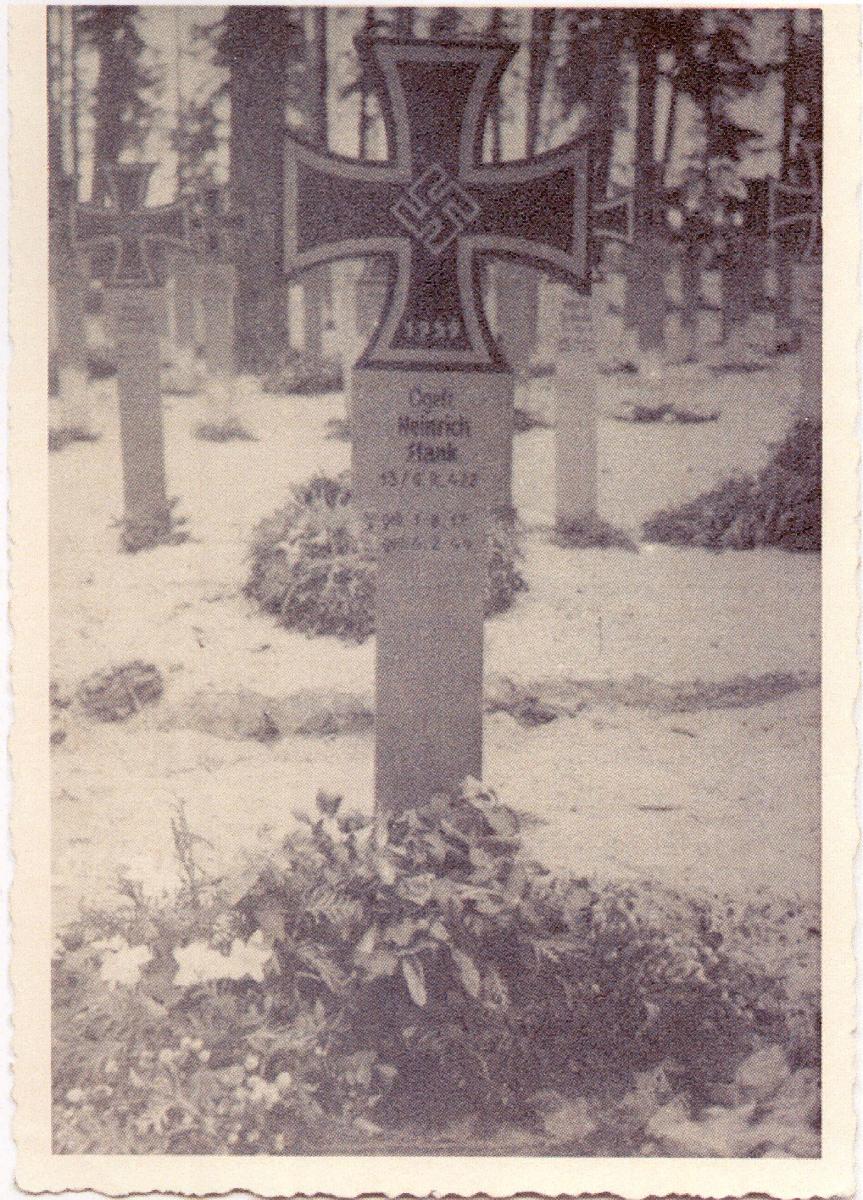

Heinrich Stank visits the grave of a friend in Russia. Heinrich was wounded in Latvia in 1944 and died in a field hospital (R. Krisch George)

Heinrich Stank visits the grave of a friend in Russia. Heinrich was wounded in Latvia in 1944 and died in a field hospital (R. Krisch George)

The invaders arrived in Selbongen on January 25, 1945; there was no armed resistance. Edith soon learned that her grandmother had overestimated the goodness of the enemy soldiers. “They didn’t treat us well. They executed lots of people, and we knew it, because we knew everybody in town.” The fear was constant in Edith’s mind:

It was always frightening when a wagon stopped in front of our house. [The soldiers] would storm into our house with their guns pointed at us. My sister Eva (7) and I (6) hung on to Mother’s dress. They took everything they liked, but they didn’t harm us.

Living under military occupation was not comfortable, but the war was over in Selbongen nearly four months before it concluded in Berlin.

According to the recollections of Emma Stank Krisch, the Red Army soldiers were allowed to do anything they desired for three days after taking the town. For the first time in the war, Germans civilians were experiencing the anger and revenge that characterized the typical Soviet soldier when he set foot on German soil. No woman—young or old—was safe in Selbongen, but as if by a miracle, only a few of the members of the branch were assaulted. Nevertheless, at least two sisters later gave birth to children of enemy soldiers.

Soon after their arrival, the conquerors impressed many Selbongen men into involuntary labor service in the Soviet Union.[11] A short time later, they began to kidnap women for the same purpose. When the word went out that this was happening, Emma Stank Krisch left her girls with her good friend Maria Niehsit and went into hiding. As Emma later wrote:

I stayed in the chicken coop all day, hoping that the Russians would not find me. The good Lord surely did protect me. So many mothers were taken to Russia, and had to leave their children behind. It was heartbreaking! Most of these mothers never came back.

At age fifty-eight, August Fischer had not served in the German army during the war, but for all practical purposes, he became a prisoner of war before the conflict ended. In early February, he and fourteen other Selbongen men were impressed into service. He had no opportunity to say good-bye to his wife and was not in great health to start with. One day while marching through deep snow, he could not go on and attempted to climb onto a wagon for a ride. As he wrote in 1948:

A Russian soldier sitting on the wagon wanted to shoot me. I said I didn’t care. He took aim at me and was about to shoot when a young sergeant came by and stopped him. Later I regretted the fact that he didn’t kill me then, because he would have spared me from a great deal of suffering.[12]

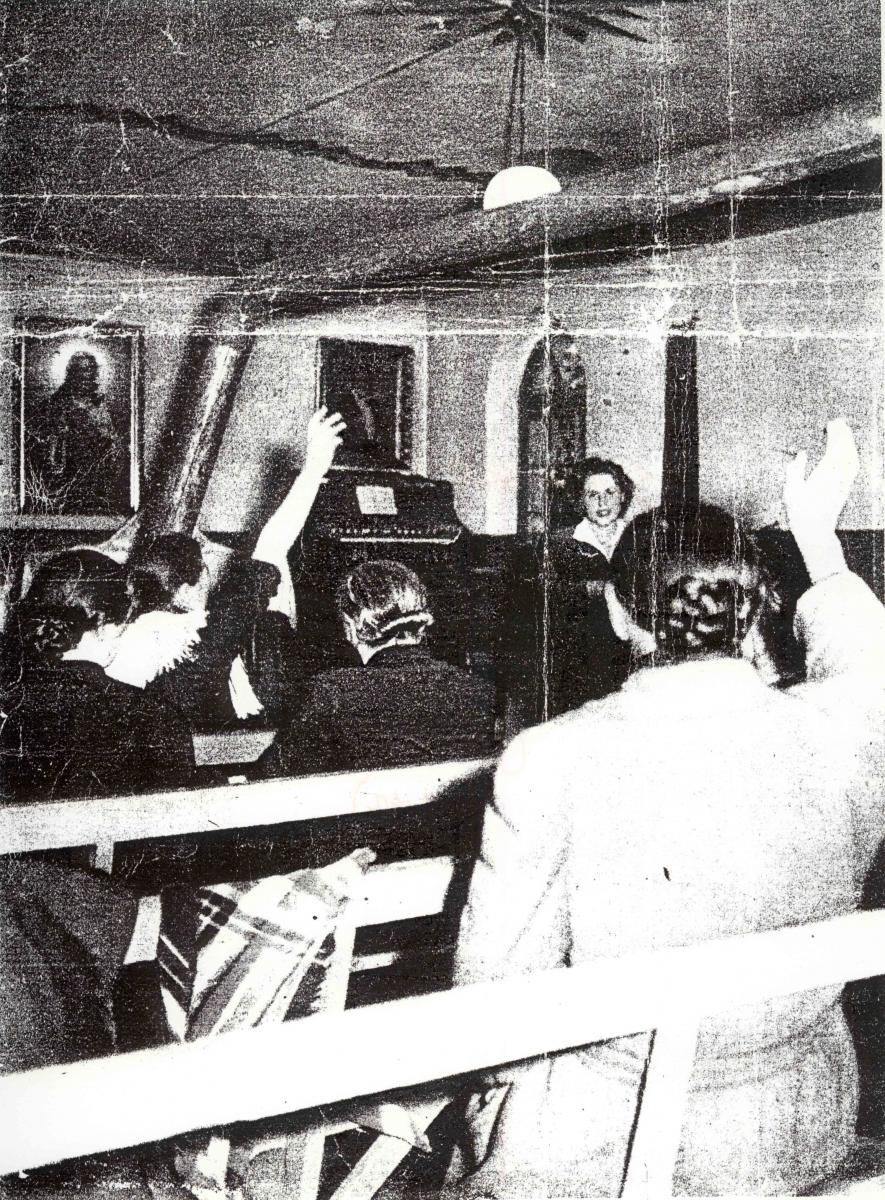

The interior of the Selbongen church in 1958. Eyewitnesses say that the décor was essentially the same during the war years.

The interior of the Selbongen church in 1958. Eyewitnesses say that the décor was essentially the same during the war years.

By March 21, August Fischer had been transported deep into Russia near the Ural Mountains. Under the terrible conditions of the transport, hundreds of Germans had already died. It was soon clear to August that a life of hard labor under grueling conditions awaited him. Right from the start, he battled illness after illness and spent much of his time in camp hospitals. “I only survived all of those illnesses because of my great energy and will to live.”

Eventually some degree of calm came back among the inhabitants of Selbongen as they sought an existence without a government to regulate matters (such as food distribution). Emma Krisch later recalled that they had always had enough to eat during the war because they lived in a rural area. However, all of that changed when the Russians arrived and stole their animals and their stored grains. She explained that they often buried food supplies in the ground to keep them from being discovered and taken by the Soviets. In response, the invaders used long metal rods to search for hidden food and valuables.

Annie Butschek recalled somebody having the idea “that we should hide everything that was really valuable to us underneath the podium in the meetinghouse. We hid nice tableware and special clothing. Nothing happened to those things, and a few months later, we were able to get them back.”

Walter Skrotzki was only five years old when the Russians invaded the town, but he recalled one item of family property that was lost: “We had a picture of Jesus Christ holding the lost lamb in his arms, and the frame for this picture looked like it was gold. So [the soldiers] wanted to find out [if it was gold] and burned it.”[13]

Walter recalled the problem of involuntary forced labor under Soviet domination:

Two of my siblings were taken by the Russians in 1945. My brother was hurt on the way to Russia and they had left him [behind]. A week later, he returned home. My sister was less fortunate and had to stay with them [in Russia] for five years. She returned in the 1950s.

Although the war was replete with senseless tragedies, a particularly sad example took place in Selbongen on Sunday, January 28, 1945. Alfred Ernst Kruska (born 1925), a young husband in the Selbongen Branch, had returned on convalescent leave shortly before the invasion. He (on crutches) and his wife, Frieda, were crossing the street toward his father’s home next to the church that Sunday morning. Still wearing his uniform, he was challenged by enemy soldiers to give them cigarettes, which he told them he did not have. They shot and mortally wounded him at the gate in front of his father’s home.

Eyewitnesses such as Renate Krisch never forgot the incident. The shots rang out while they were holding Sunday School in the church next door to the Kruska home. Adults and children alike first looked out the window and then rushed out to see what had happened. Renate described the event in these words:

There was Frieda Butschek [Kruska] leaning over her lifeless husband, and she was uncontrollably wailing—not just crying. The blood, of course, was very visible on the white snow and very disturbing to me. It was only minutes before his parents were there and the whole neighborhood. The Russians kept on talking to the adults and looked very mean and told them to go into the house.[14]

Alfred was laid to rest in a grave next to the church, just a few feet to the right of the front stairway. Helmut Mordas (born 1933) later wrote that “the burial took place two or three days later and in the dark of night, because we were scared of the Russians. We were so sad. Alred’s father made the coffin.”

Helmut Mordas recalled a Sunday when the Russian soldiers went through town in search of women and girls:

Several women gathered in church, hiding out with Brother Kruska, and I was there too. We sang the hymn “Come, O Come, Thou Day of Glory” on page twenty-six. After the hymn, we knelt down and two or three sisters and Brother Kruska prayed. We could feel the Spirit of God among us. Despite the fact that the singing could be heard out on the street, no Russian entered the church. That strengthened our faith that God had heard our prayers.

Erich Stank (born 1933) gained a testimony of the Savior Jesus Christ at the age of thirteen during a particularly harrowing event in February 1945. As he later wrote,

About fifteen of us (four families) found ourselves in a life-threatening situation. About fifteen Russian soldiers pointed their rifles at us to shoot us. In this dangerous situation, my mother stood between their bullets and us children (five of us). She said, “Children, take each other by the hand.” Then she sang the hymn, “Abide with Me, Fast Falls the Eventide.” . . . I was only thirteen years old and I wanted to live. I prayed to my Father in Heaven, told him that I wanted to live, and made a pact with him: if he allowed me to live, I would live according to his commandments and laws.[15]

It should not be assumed, of course, that every Soviet or Polish soldier was capable of inhumane acts. Helmut Mordas expressed this thought years later in these words: “In all fairness, I have to say that where there were lots of children, [the conquerors] left the family one cow and a few chickens so that the children would have something to eat and some milk to drink.” Otherwise, all animals were taken and sent eastward. Helmut was forced to herd animals in that direction for six weeks until he could escape and return to Selbongen.

The grave of Heinrich Stank in distant Russia (R. Krisch George)

The grave of Heinrich Stank in distant Russia (R. Krisch George)

In the spring of 1945, Emma Krisch was working in the garden when an enemy soldier approached her. She walked in the opposite direction, pretending not to see him:

I knew that he was following me. I kept on walking to the neighbors, the Kruska’s, but I did not make it. He picked up a piece of wood, a board, and hit me on the head from behind. Brother Kruska came out of the house and scared him off. Otherwise, he could have killed me. Here, again, the Lord was with me and protected me because I was needed to take care of my two little girls.

All eyewitnesses agreed that by May 1945, when the war ended, Brother Kruska was still conducting church services in the Selbongen Branch. There had been brief interruptions when the Russians arrived, and the soldiers actually inhabited the hall for a week or two, but the Saints there did their best to restore order in the Church at a time when order was not possible in so many other aspects of life.

If the Saints in Selbongen thought that the Soviets were brutal rulers, they found out differently when the region was turned over to the Polish. Emma Krisch later wrote that any offenses committed by the Russians were surpassed by the Polish. “Nothing was safe; everything was fair game for the Poles. If they wanted something they just took it from the Germans.”

At eighteen years of age, Annie Butschek was a prime target for abuse by the conquerors. She must have been quite scared when called to the local police office one day. She described the experience in these words:

They brought us to the Polish GPU (police) and we had to answer questions about what we did during the war and if we were a member of the Party in any way or even a member of the BDM. After I answered all these questions, a secretary took a ruler and hit me in the face a few times after which I was allowed to leave. They brought me to a cellar space below a living room, and I had to climb into it through a door in the floor. All the others who came with us were already in there. The people asked me if they had hit me and I responded that it was nothing compared to all of this. A little later, they opened the door and we could climb out. We got a little to eat.

Annie’s mother called her treatment “nothing compared to all that was being inflicted on women all over East Prussia.”

Life in the Selbongen region was helter-skelter at best for several months after the war. For example, in the fall of 1945, Martha Krisch Pilchowski (born 1909) was ordered by Polish soldiers to vacate her home within thirty minutes. Along with her sons and her sister-in-law, Antonie, and some belongings (a maximum of thirty pounds per person), they began the trip to Germany by walking thirty miles to a railroad station. Under deplorable conditions, they were transported to eastern Germany. A trip that once took two days now lasted five weeks. The refugees were cold, starving, and sick, and Martha’s health failed. According to her sister-in-law Emma Krisch, “She died en route to East Germany. When the train stopped, the relatives wrapped her body in a blanket and left it on the platform of a train station. They were not allowed, nor was there time to bury her.”[16]

The youth of the area faced another particular challenge. Helmut Mordas wrote that “we young people didn’t have any future in those days. There was no school and no occupational training. We stayed alive by working the farms and the gardens.”

Thinking back about the challenges faced by his widowed mother, Emilie, during the horrific last days of the war, Walter Skrotzki offered this short statement: “My mother was very faithful. Nothing could take her away from the Church.”

“We were among the first members who left Selbongen,” recalled Heinz Grühn.

We stayed in Selbongen until August 20, 1947, when we took a transport out of the town. Because my father worked for the police, he left for western Germany in 1945. For him, it was too dangerous to stay. The Russians were not the problem but rather the Polish. When we left Selbongen, we were assigned to a transport train in which we slept on straw for two weeks with thirty-one people.

All through the years of 1946 and 1947, August Fischer tried to maintain his health enough to do the work required of him in the POW camps of Russia. It seemed like his work was always outdoors, where he was subjected to numbing cold and wet conditions. Fighting lice and the illnesses of other prisoners in his immediate vicinity, he rarely had a warm meal or a warm place to sleep. On the few occasions when he was given a delousing or a shower in lukewarm water, he was grateful to enjoy any condition resembling cleanliness. However, his health was never good and he narrowly escaped death on several occasions.

As a POW, Wilhelm Krisch was first taken to the United States and interned in Alabama. In 1946 he was sent to Scotland and was released there in 1947. Unfortunately, he dared not return to Selbongen. By that time, the town was under Polish administration. While Latter-day Saints in all other German towns that became Polish after 1945 were compelled to leave and go west to Germany, this was not the case in Selbongen. The Polish county government there allowed (or forced) only some of the surviving Germans in the branch to emigrate. Under those circumstances, Wilhelm Krisch felt it safer to stay in West Germany and wait until his family could come to him. As the years went by, he decided to immigrate to the United States with his brother. He was not reunited with his wife and his children until they were allowed to leave Selbongen and travel to the United States in 1957.

The list of illnesses suffered by August Fischer for three years as a forced laborer in Russia is long, amazing, and discouraging. Twice he was told that a release was forthcoming and each time was disappointed. He was finally able to establish communications with his family in 1947, and this bolstered his spirits. Unfortunately, by the time he was released in 1948, his health was permanently weakened. He was not allowed to return to his wife and family in Selbongen but was sent to western Germany and ended up in Wolfshagen near Kassel, where he was put into a hospital. It was there that he concluded his memoirs of the years in Russia with these words: “I don’t know how long I will stay in this hospital; my illnesses are fairly serious.” He had contracted tuberculosis in Russia and died on September 9, 1951, in a Heidelberg hospital. His family was still in Selbongen, and he had not seen them since being kidnapped in February 1945.

The members of the Selbongen Branch who stayed there after World War II were allowed to continue to meet in the church but were required to conduct their services in the Polish language. They translated their songs and their talks into Polish, but their German heritage refused to be totally conquered. After 1946, theirs was the only branch of the Church for hundreds of miles; they were isolated, except for periodic visits from leaders of the Church from East Germany.[17]

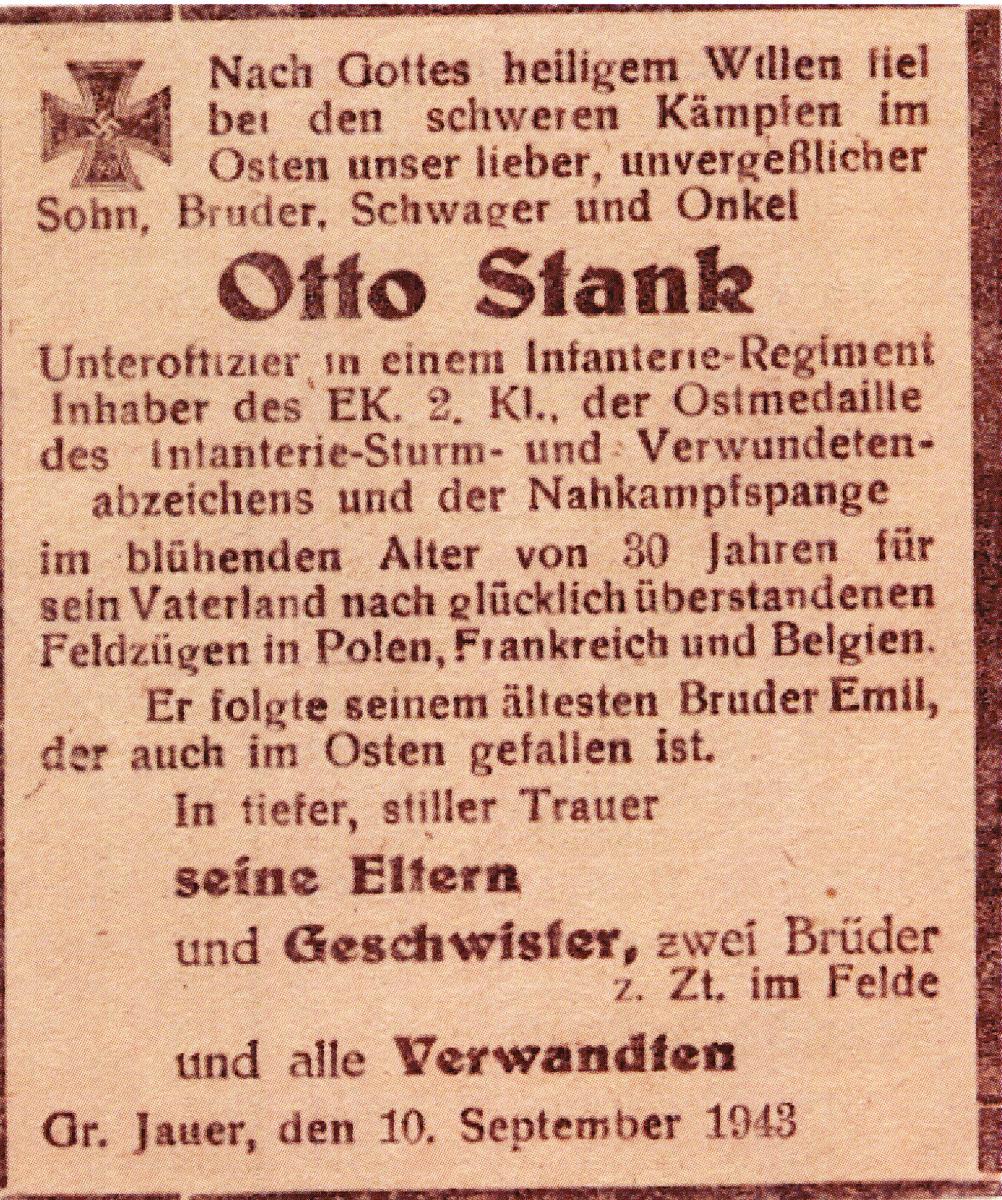

The newspaper obituary for Otto Stank in 1943 (R. Krisch George)

The newspaper obituary for Otto Stank in 1943 (R. Krisch George)

Beginning in the 1950s, the Latter-day Saints in Selbongen sought a way to immigrate to Germany one by one. For example, Helmut Mordas availed himself of illegal means to leave Poland and travel to West Berlin. By 1974, the branch ceased to exist. As of this writing, the LDS meetinghouse in Selbongen (now Zelwagi, Poland) is being used by the Catholic Church. The grave of Alfred Kruska is carefully maintained.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Selbongen Branch did not survive World War II:

Auguste Bauik b. Rhein/

Manfred Johannes Bojahra b. Selbongen, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 24 Jun 1936; son of Alfred Fritz Bojahra and Hedwig Louise Kruska; d. diphtheria Selbongen 5 May 1940 (Sonntagsstern, no. 21, 23 Jun 1940, n.p.; CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 156; IGI; PRF)

Julius Czwiowski b. Liebenberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 7 Jul 1870; son of Samuel Czwikowski and Eva Polkowski; bp. 6 Oct 1929; conf. 6 Oct 1929; m. Kumilsko, Ostpreussen, Preussen 3 May 1896, Wilhelmine Gutowski; 4 children; d. old age Selbongen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 5 May 1940. (Sonntagsstern, no. 21, 23 Jun 1940, n.p.; FHL Microfilm 245749; IGI)

Horst Fritz Fischer b. Turnowen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 12 Aug 1923; son of Michael Fischer and Wilhelmine Jedamzik; bp. Selbongen, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 1 Jun 1932; conf. Selbongen 1 Jun 1932; ord. deacon Selbongen 1 May or Oct 1939; k. in battle 13 Mar or May 1943 (CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 23; IGI; PRF)

Walter August Fischer b. Selbongen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 5 Mar 1920; son of August Fischer and Amalie Bukowski; bp. Selbongen 28 Apr 1928; conf. Selbongen 28 Apr 1928; ord. deacon Selbongen 24 Jun 1934; ord. teacher Selbongen 6 May 1938; MIA Luga, Sabzje, Russia 1 Jan 1944 or d. 10 Mar 1944 (CHL Microfilm 2448 Pt. 27 no. 5; IGI; PRF; www.volksbund.de)

Willy Fritz Fischer b. Selbongen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 11 Jul 1921; son of August Fischer and Amalie Bukowski; bp. 14 Jul 1929; conf. 14 Jul 1929; ord. deacon 13 Sept 1936; ord. teacher 1 Oct 1939; d. 20 Jul 1944 (CHL Microfilm 2448 Pt. 27 no. 6; IGI; PRF)

Johann Fladda b. Neu Ukta, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 22 Feb 1885; son of Michael Fladda and Friedrike Czesny; bp. Selbongen, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 6 Jul 1930; conf. Selbongen 6 Jul 1930; ord. deacon Selbongen 25 Dec 1938; m. Nicolaiken, Ostpreussen, Preussen 11 or 19 Jul 1919, Marie Hoffmann; 1 child; d. Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 27 Jan 1945 (CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 11; IGI; PRF)

Paul Fladda b. Selbongen, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 4 Dec 1901; son of Karl Fladde and Charlotte Gruenske; bp. Selbongen 6 Nov 1924; conf. 6 Nov 1924; ord. deacon Selbongen 1 Nov 1925; ord. teacher Selbongen 26 Oct 1930; m. 16 Nov 1928, Anna Brisewski; d. POW France 28 Sep 1945 (Krisch-George; CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 9; IGI; PRF)

Wilhelmine Giesewski b. Selbongen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 20 Jul 1878; dau. of Samuel Giesewski and Karoline Eichel; bp. 3 Jul 1924; conf. 3 Jul 1924; m. 2 or 3 Oct 1903, Emil Piotrowski; 5 children; d. Selbongen 13 or 17 Feb 1940 (Sonntagsstern, no. 17, 26 May 1940, n.p.; CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 49; NG-IGI; AF; PRF)

Heinriette Grudda b. Neuwalde, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 31 Mar or May 1868; dau. of Johann Grudda and Marie Marzenowski; bp. 15 Aug 1924; conf. 15 Aug 1924; m. 24 Nov 1889, Fritz Walter; d. 11 Jun 1943 (CHL Microfilm 2448 Pt. 27 no. 92; IGI)

Auguste Huebner b. Plowczen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 17 Dec 1872; dau. of Samuel Huebner and Catharine Staschewski; bp. 4 Jun 1932; m. —— Sabotka; d. 19 Oct 1942 (IGI)

Johann Kelbch b. Klein Schwignainen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 28 May 1896; son of Leopold Kelbch and Wilhelmine Schliski; bp. 30 June 1917; conf. 30 Jun 1917; d. 1940 or 1942 (CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 131; IGI)

Martha Krisch b. Ododyen, Johannesburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 19 Jan 1908; dau. of Gottlieb Krisch and Marie Penski; bp. 23 Oct 1922; conf. 23 Oct 1922; m. Ostpreussen, Preussen 6 or 9 June 1930, Rudolf Pilchowski; d. as refugee Feb 1945 (Krisch-George; CHL Microfilm 2448 Pt. 27 No. 136; IGI)

Adolf Ernst Kruska b. Selbongen, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 29 Oct 1916; son of Adolf Kruska and Amalie Fischer; bp. 20 Jun 1925; conf. 20 Jun 1925; ord. deacon 13 May 1932; ord. teacher 6 May 1938; ord. priest 26 Aug 1943; m. Nikolaiken, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 6 Nov 1942, Frieda Buschek; k. by Russian soldiers 28 or 29 Jan 1945; bur. at Selbongen LDS Church (Krisch-George; CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 91; IGI)

Anna Kulinna b. Pietzarken, Angerburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 10 Oct 1903; dau. of Friedrich Kulinna and Auguste Masannek; bp. 1 Aug 1923; conf. 1 Aug 1923; m. 14 Nov 1930, Richard Jestremski; k. by Russians 1945 (CHL Microfilm 2448 Pt. 27 no. 30; IGI)

Auguste Massannek b. Siemanowen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 18 Jun 1864; dau of Daniel Massannek and Justine Schwüller; bp. 16 Aug 1923; conf. 16 Aug 1923; m. 15 Apr. 1892, Friedrich Kulinna Sr.; d. exposure 1945 (CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 37; IGI)

Margott Hildegard Mordas b. Selbongen, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 27Aug 1929; dau. of Gustav Mordas and Anna Stopka; bp. 29 Aug 1937; conf. 29 Aug 1937; d. typhoid 27 Aug 1945 (Mordas-Hohmann; CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 46; IGI; PRF)

Gustav Pieniak b. Selbongen, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 24 Aug 1906; son of Gottlieb Pieniak and Auguste Benzka; bp. 19 Sep 1937; conf. 19 Sep 1937; ord. deacon 25 Dec 1938; ord. teacher 25 Apr 1943; ord. priest 1 Oct 1944; m. Nikolaiken, Ostpreussen, Preussen 29 Dec 1933, Anna Marie Heyduck; 2 children; d. Ural Tu, Russia 22 Mar 1945 (CHL Microfilm 2448 Pt. 27 no. 165; IGI)

Fritz Karl Piotrofski b. Selbongen, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 10 Jan 1917; son of Emil Piotrofski and Wilhelmine Giesenki; bp. Selbongen 12 Sep 1925; conf. Selbongen 12 Sep 1925; lance corporal; d. 30 May 1944; bur. Cassino, Italy (CHL Microfilm 2448 Pt. 27 no. 52; IGI; PRF; www.volksbund.de)

Martha Karoline A. Przygodda b. Bettmar, Braunschweig 17 Jul 1899; dau. of August Przigodda and Frieda E. Hentis; bp. 19 Sep 1924; conf. 19 Sep 1924; d. surgery 23 Aug 1942 (CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 82; IGI)

Heinrich Friedrich Schirrmann b. Gross Jauer, Ostpreussen, Preussen 20 or 27 Feb 1920; son of Wilhelm Schirrmann and Amalie Schwalgin; bp. 9 Sep 1928; conf. 9 Sep 1928; k. in battle 1944 or 1945 (CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 62; IGI)

Waldemar Ernst Schirrmann b. Gross Jauer, Ostpreussen, Preussen 30 Aug 1925; son of Wilhelm Schirrmann and Amalie Schwalgin; bp. 2 Aug 1936; conf. 2 Aug 1936; lance corporal; k. in battle St. Pol, France 9 Nov 1944; bur. Bourdon, France (CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 No. 65; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Emil Skrotzki b. Salza, Lötzen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 4 Feb 1904; son of Gottlieb Stank and Heinriette Skrotzki; bp. 15 or 16 May 1924; conf. 16 May 1924; ord. deacon 2 Nov 1925; ord. teacher 20 Mar 1928; ord. priest 14 Jul 1929; ord. elder 13 Mar or 5 Sep 1932; former branch president; m. Salza, Ostpreussen, Preussen 14 Oct 1927, Emilie Grabowski; 6 children; policeman; k. in battle San. Kp. 1/

Heinrich August Stank b. Gross Jauer, Lötzen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 1 Aug 1917; son of Gottlieb Stank and Heinriette Skrotzki; bp. 25 Sep 1927; conf. 25 Sep 1927; lance corporal; d. wounds Field Hospital 2/

Otto Paul Stank b. Gross Jauer, Ostpreussen, Preussen 20 Jul 1913; son of Gottlieb Stank and Heinriette Skrotzki; bp. 31 May 1926; conf. 31 May 1926; noncommissioned officer; k. in battle 4 km north of Kelkowo b. Mga, Russia 12 Aug 1943; bur. Sologubowka, St. Petersburg, Russia (Krisch-George; CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 No. 77; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Werner Stank b. Fasten, Sensburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 15 Oct 1940; son of Fritz Stank and Frieda Hahn Stank; d. heart ailment Fasten 8 Apr 1942 (Krisch-George; CHL Microfilm 2448 pt. 27 no. 185; IGI; PRF)

Otto Paul Stank

Otto Paul Stank

Heinrich August Stank

Heinrich August Stank

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Emma Stank Krisch and Renate Krisch George, interview by the author, Fruit Heights, Utah, May 25, 2006.

[3] Günther Skrotzki, interview by the author in German, Strausberg, Germany, June 8, 2007; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by the Judith Sartowski.

[4] Heinz Grühn, telephone interview with Judith Sartowski, May 8, 2008.

[5] Renate Krisch George, autobiography (unpublished, 2002), 9–10; private collection.

[6] Wilhelm Krisch, autobiography, 122; private collection.

[7] Emma Stank Krisch, “How and Why We Came to America” (unpublished, 1994); private collection.

[8] Sonntagsgruss, no. 7 (April 5, 1942): 28.

[9] Annie Butschek Skrotzki, interview by the author in German, Strausberg, Germany, June 8, 2007.

[10] Edith Mordas Hohmann, autobiography (unpublished); private collection.

[11] Helmut Mordas claims to remember clearly that this “manhunt” occurred on April 10, 1945. Helmut Mordas, “Mein Bericht: Geschrieben aus meiner Erinnerung von 1939 bis 1957” (unpublished); private collection.

[12] August Fischer, “Meine Erinnerungen 1945–1948” (unpublished); private collection.

[13] Walter Skrotzki, interview by the author in German, Munich, Germany, August 9, 2006.

[14] George, autobiography, 18.

[15] Erich Stank, report (unpublished, 2005); private collection.

[16] Emma Stank Krisch, report, (unpublished, 2006).

[17] Walter Krause and Henry Burkhardt each visited the Selbongen Branch on a number of occasions.