Schneidemühl Branch, Schneidemühl District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 397-411.

The city of Schneidemühl was not located in the center of the district of the same name, but at the end of 1939, there were substantially more priesthood holders in that branch than in any other. Perhaps that was the reason for the selection of Schneidemühl as the home of the district. During the war, the branch president was Wilhelm Jonischuss, and his counselors were Richard Rieve and Friedrich Wolff.[2]

This branch was a fine example of the role played by larger families in smaller branches. Fritz Birth had eleven children and Johannes Kindt had seven (from two wives—his first wife had died). Together the two families made up almost one-quarter of the branch population.

| Schneidemühl Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 7 |

| Priests | 3 |

| Teachers | 4 |

| Deacons | 3 |

| Other Adult Males | 12 |

| Adult Females | 44 |

| Male Children | 3 |

| Female Children | 6 |

| Total | 82 |

For the duration of World War II, the Schneidemühl Branch met in rented rooms on Gartenstrasse. The address was house 31, in the main floor of the first Hinterhaus.

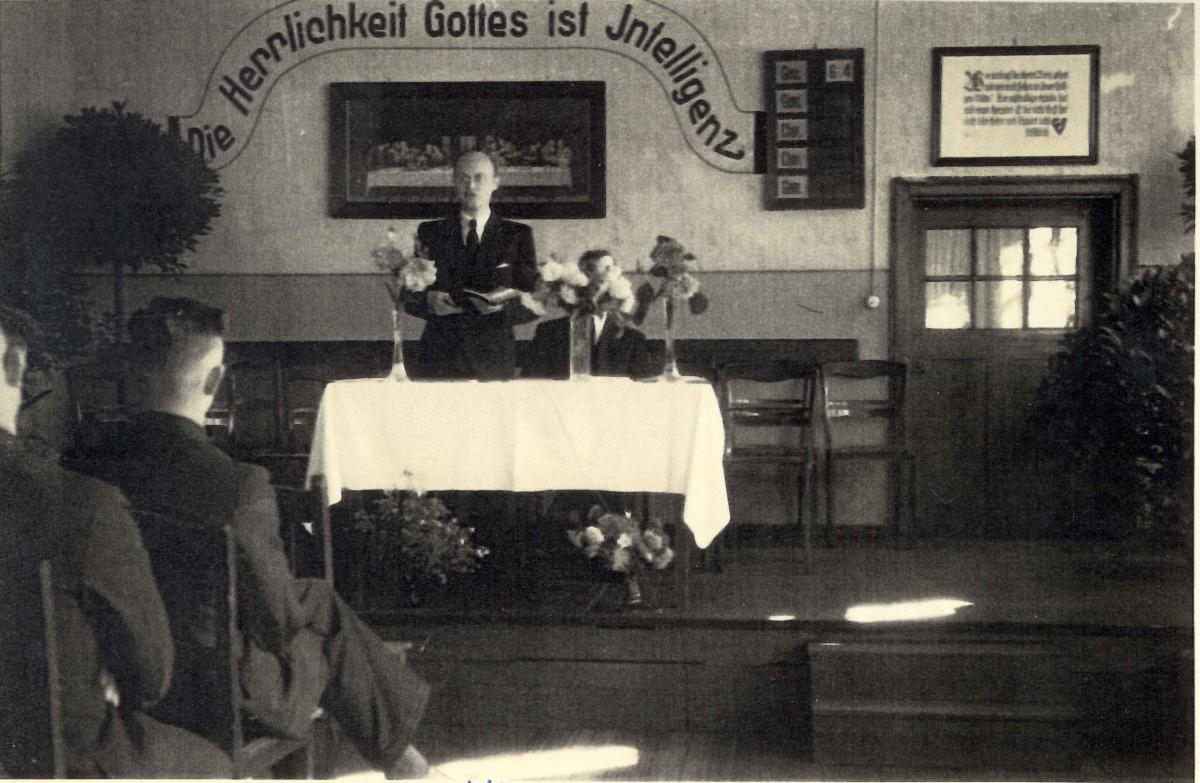

Hans Kindt (born 1922), the eldest child of district president Johannes Kindt, recalled that the branch rooms in the Hinterhaus included a main meeting hall, three or four small classrooms, a cloakroom, and restrooms. He remembered that the phrase “The Glory of God is Intelligence” was painted on the wall at the front of the chapel. There was a pump organ, and the rooms were heated by a stove.[3]

Ruth Gärtner (born 1923) recalled that a picture of the prophet Joseph Smith hung on one of the walls. Her family’s Church attendance was stellar, thanks to the character of her mother, a “very dedicated member of the Church”:

We had to be [in church] rain, snow, or ice. We walked an hour to church for Sunday School and went back home. Then at 7:00 was the sacrament meeting, and then we walked another hour, and by 9:00 we were back home. So we walked four hours on Sundays.[4]

Mission Supervisor Herbert Klopfer came from Berlin in about 1940 to visit the Saints in Schneidemühl. (W. Kindt)

Mission Supervisor Herbert Klopfer came from Berlin in about 1940 to visit the Saints in Schneidemühl. (W. Kindt)

President Johannes Kindt was not a follower of Adolf Hitler and encouraged his sons to avoid involvement with the Hitler Youth.[5] According to Hans, “He told me to say that we didn’t have the money to pay for the uniforms. So [the leaders] gave me the uniform and then I didn’t have an excuse. I liked it at first because I liked the competition of sports.”

Hans’s younger brother, Walter (born 1923), planned to be a surveyor and needed to be in the organization or risk losing his apprenticeship. Walter was a talented young man and eventually became the leader of a group of 350 boys. On one occasion, a friend wondered why Walter did not attend Hitler Youth activities on Sundays, so on the next Sunday, all 350 boys came to the Kindt home to pick Walter up. He went with them, but he was still able to attend Sunday School promptly at 10:00 that morning. “Already, in my early life, I worked with the principle of faith.”[6]

The first meeting on Sundays was for the teachers and began at 9:00 a.m., followed by Sunday School. Sacrament meeting was held in the late afternoon. The Kindt family lived at Bölkestrasse 6, about fifteen minutes from church, and had plenty of time to go home between meetings for Sunday dinner. Most parents did not bring their little children to sacrament meetings in those days due to the lateness of the hour, but the children had already partaken of the sacrament during Sunday School.[7]

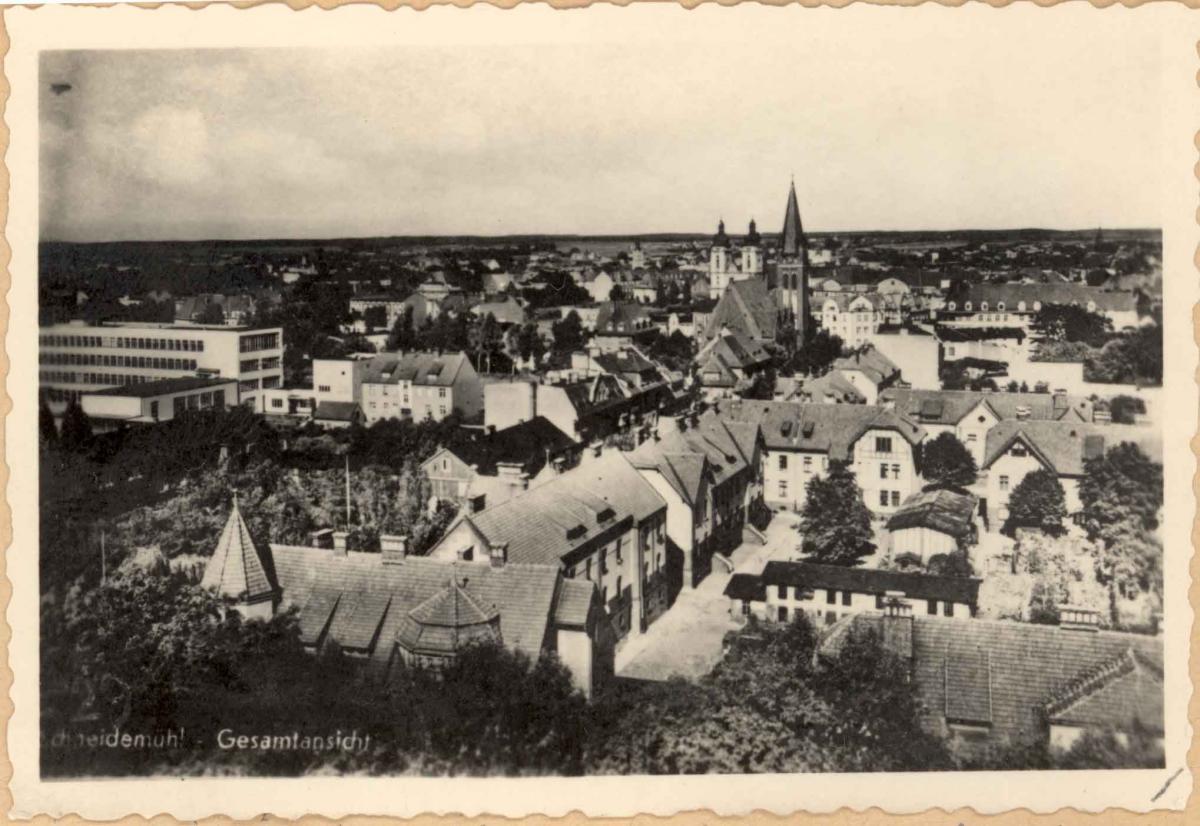

The city of Schneidemühl in about 1940 (W. Kindt)

The city of Schneidemühl in about 1940 (W. Kindt)

Walter was the Sunday School secretary in 1939. He recalled recording an average attendance of 110 persons. Although this number exceeded the total population of the branch at the time, it is quite credible. All over Germany, it was the practice of the Saints to invite friends to Sunday School, especially children.

Hans Kindt was inducted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst while doing an apprenticeship in tailoring. For the next nine months he practiced his craft while attached to a quartermaster unit behind the lines in Lithuania and Russia. Upon returning home, he worked only one month in a tailor shop before his draft notice arrived in December 1941. While in basic training in Thorn, West Prussia, he was one of twenty men tested as possible radio men. He was musically inclined and thus quickly learned Morse code, winning the job.

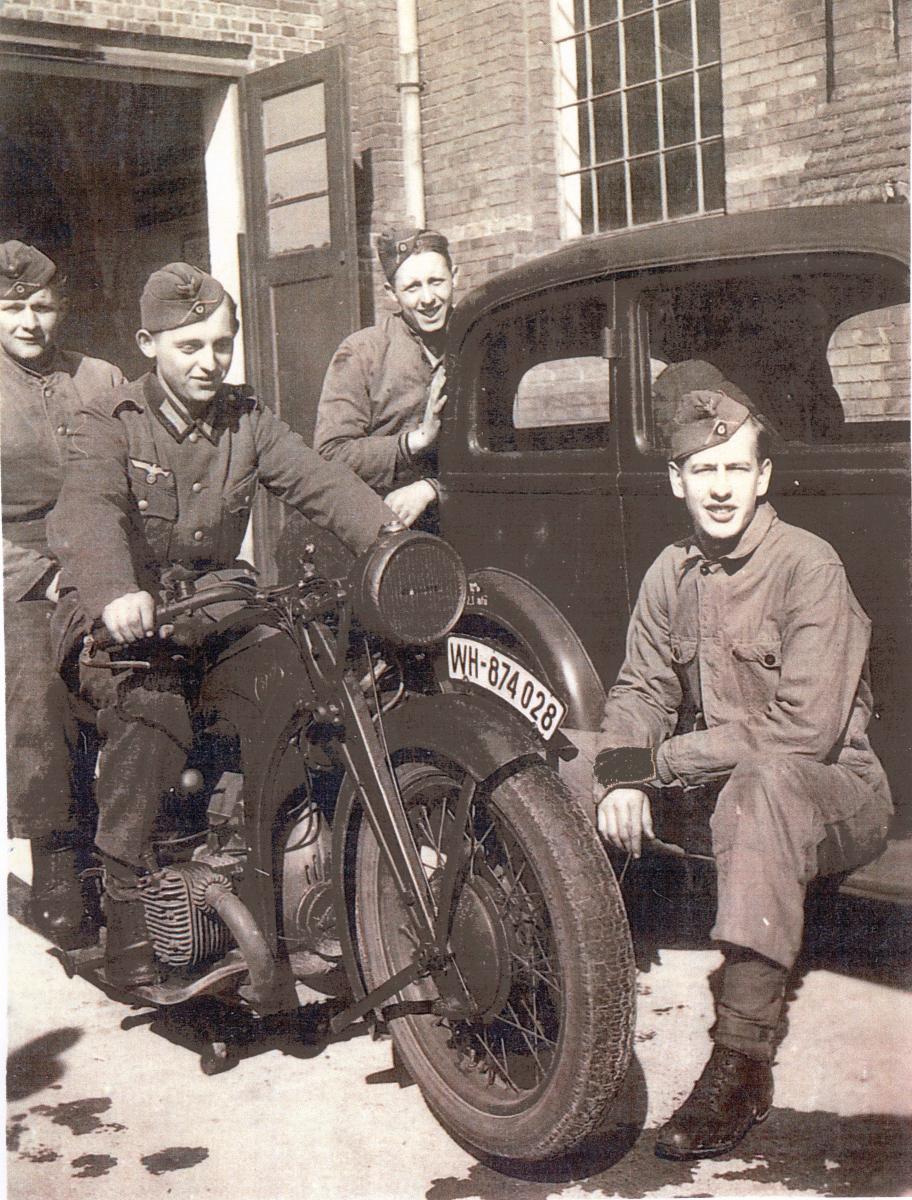

Walter Kindt (front right) with his Hitler Youth group (W. Kindt)

Walter Kindt (front right) with his Hitler Youth group (W. Kindt)

Ruth Gärtner was doing an apprenticeship as a seamstress when she was called into the Reichsarbeitsdienst in 1940. She spent the first six months working on a farm with other girls as replacements for the young men who had been drafted. The next six months saw her in Berlin, where she helped run the S-bahn commuter trains through town. Air raids were already plaguing the city, and riding the S-bahn at night was a bit risky. She later recalled a humorous incident that took place while the air raid sirens were blaring:

One night I was still in the shower [when the alarm sounded], and a girl [air raid warden] had to go around and see if everyone was out of the rooms, and she said, “Is somebody still in the shower?” I said, “Yes, I am!” and she said, “Come out!” and she grabbed me by my hand, and she didn’t allow me to go back and get my clothes. I was just wrapped in a towel, and the bombs were falling. And we ran and had to go over a big yard into the bunker; I was sitting all night in that towel wrapped around me, that’s all I had on.

Friedrich “Fritz” Birth and his wife, Emma, already had eleven children when World War II began. The family had two sources of income—Fritz’s glass shop in town and Emma’s small grocery store in a side room of the family home in a suburb of Schneidemühl. The children were instrumental in the operations of both businesses.

When the American missionaries were evacuated from Germany in August 1939, a vacuum was created that could only be filled by German Latter-day Saints. In 1941, the Births’ daughter, Edith Gerda (born 1921), was called to serve as a full-time missionary in the mission office in Berlin. “My heart stood still. Why me? . . . I was nervous. . . . And I needed greater faith.” She served honorably until November 3, 1943—just three weeks before the mission office was destroyed.[8]

At age seventeen, Walter Kindt began serving his country. He first spent three months in the Reichsarbeitsdienst, helping to build a dam near Pogegen, East Prussia. From there, he was fortunate to attend church in both Tilsit and Königsberg. At one point during this term of service, Walter Kindt and his elder brother Hans were both home on leave and went to church on Sunday, June 22, 1941. That morning, the German army attacked the Soviet Union. Upset by this violation of the Ten Commandments, Walter predicted to his brother that Germany could not win the war because the invasion had begun on the Sabbath Day.

While still in the Reichsarbeitsdienst, Walter volunteered for military service and by doing so secured a much better wage. He spent seven months in basic training in Pasewalk near Stettin. While he was home on leave toward the end of his basic training, his unit was transferred to the Soviet Union, but Walter was not sent with them. At first, Walter was disappointed to be separated from his friends, but he later learned that all twenty-four of his comrades were killed on the Eastern Front. Years later, he wrote, “This woke me up, and I offered a special prayer of thanks to my Heavenly Father for being alive.”

Not following his comrades to the Soviet Union, Walter was instead sent to the Western Front. In France, he resolved to keep the Lord’s commandments though he was out of contact with the Church. He consistently said his prayers and faithfully mailed his tithing back to Germany to his branch president.

The district conference was always a grand event that took place on a Saturday and Sunday. It was an especially exciting time for the youth, who were generally in small numbers in each branch. Ruth Gärtner recalled how all of the local youth escorted the youth from other branches to the Schneidemühl railroad station on Sunday night to send them home to other towns. On one such occasion in 1942, Siegfried Jeske of the Driesen Branch asked Ruth if she would write to him. She did so, but he was soon in the army, and their relationship was one of correspondence over long distances.

By April 1942, Hans Kindt was in a combat zone on the Eastern Front. As a radio man, he was right up at the front line. He earned his combat infantry badge (awarded after three combat engagements) right away. By October 1942, the German army had advanced far into enemy territory, but Soviet resistance was stiffening. At one point, Hans’s unit was surrounded and cut in half. Fortunately, they were able to fight their way out of the predicament.

Like so many other Latter-day Saint soldiers, Hans had no desire to kill enemy soldiers. However, as a radio man at the front, he also carried a rifle and was expected to fight. He later explained how he resolved the conflict in his mind and in practice:

Very soon in [battle] I discovered that when I was aiming after fleeing Russian soldiers with the tracer bullets, I discovered how closely I [came to hitting] [one], and then I said, “I could have killed him. Maybe he had a wife and children.” And so from there on I would always aim a little higher. I never told anyone for years and years because they would think I was a coward. But that was my decision, and that’s what I did. So I was lucky; I got through it, I didn’t have to kill anyone.

In the fall of 1942, Hans contracted diphtheria and dysentery. He was sent home on leave, then was assigned to a post in France, where he served from October 1942 to February 1943. After another furlough at home, he returned to the Soviet Union in April 1943.

Members of the Schneidemühl Branch pose for a picture in the courtyard next to the meetinghouse. (S. Dunbar)

Members of the Schneidemühl Branch pose for a picture in the courtyard next to the meetinghouse. (S. Dunbar)

Hans Kindt came within inches of being killed in July 1943. During a Soviet offensive, he was given the order to radio for tank support then to destroy his equipment and join the retreat. However, he decided that he could simply disconnect the antenna and take his radio with him. While doing so, he saw a Red Army soldier shoot at him from more than one hundred yards away. He felt the bullet pierce his arm, and he fell down in shock. He lay there all night while the Soviets infiltrated the German lines. He unbuttoned his shirt and, using a flashlight, learned that the bullet had cut across his chest from left to right and then passed through his right arm. The flesh on his chest was wide open. The next morning, a buddy ran by and Hans called for help:

[My comrade] didn’t want to [take me along,] but then he came, and I was hanging on to him and completely exhausted. That was a time in my life where I said to him, “Leave me. There’s no hope anyway,” and so he gave me the courage to go because he could see there was a hill going down, and we would find cover there. He saved my life. I was still walking, hanging on.

Members of the Schneidemühl Branch during a picnic in a nearby forest (W. Kindt)

Members of the Schneidemühl Branch during a picnic in a nearby forest (W. Kindt)

Initially, because he was nowhere near a bona fide medical facility, Hans’s gaping flesh wound was simply taped together. By the time a surgeon was found, the wound could no longer be repaired cosmetically, and he had a ghastly scar that would serve as a reminder of the experience for the rest of his life. He convalesced in a hospital in Czechoslovakia near the German border. His arm was taped up to his shoulder “in a primitive fashion,” and the wound refused to heal for months due to recurring infections. After nine months, he was released and eventually gained full use of and strength in his arm. By then it was the spring of 1944.

At age ten, Werner Birth (born 1932) was inducted into the Jungvolk program with his classmates. With the war at a high pitch, the youngsters were given some training with rifles “perhaps twice a year.” When it came time to learn how to box, Werner protested. He was not interested in hitting his friends.[9]

The first Church assignment given Werner Birth was that of usher. He later clearly recalled the instructions he was given: “‘Stay by the door, and when we have the sacrament, don’t let anyone in.’ So I put my shoulder under the [door] handle so nobody could get it open. I must have been pretty small at the time.”

Four young men and a young lady contribute to the spirit of the branch meetings through their musical talents. (W. Kindt)

Four young men and a young lady contribute to the spirit of the branch meetings through their musical talents. (W. Kindt)

During the first years of the war, there were few disturbances to life in Schneidemühl. Esther Rieve (born 1926) was similar to teenagers all over Germany in that she was less interested in the war than she was in her apprenticeship program, which was to last for three years. She was trained in the fine points of salesmanship in a small store. “In the evenings we came home, and it was so dark [due to blackout regulations] that we could hardly see our own hands.”[10]

In 1943, Esther was assigned to work on a farm as part of the government’s Pflichtjahr program. That assignment lasted six months, after which she was required to work in an underground aircraft factory near Berlin.

In March 1944, Johannes Kindt was pleased to have sons Walter (left) and Hans home on furlough at the same time. (W. Kindt)

In March 1944, Johannes Kindt was pleased to have sons Walter (left) and Hans home on furlough at the same time. (W. Kindt)

As air raids brought destruction to Schneidemühl, there were ample reasons to wonder who or what would be spared and who or what would be lost. Ruth Gärtner recalled the case of Sister Bauer of the Schneidemühl Branch:

She was young and married, and she had a beautiful apartment just all decorated beautifully, and she came home [after church], and a bomb had destroyed her house. . . . I could not believe it because my mother had always said, “If you keep the commandments, nothing will happen to you.” And I said, “Why did this happen to her?” . . . We had a lot of whys.

Edith Birth had met Helmut Kinder of Chemnitz while on her mission. In early 1944, he visited her in Schneidemühl, and soon the two were engaged to be married. When he was transferred from France to the Eastern front, she became seriously concerned for his welfare; her eldest brother, Gerhard, had been killed there in 1942 and another brother, Nephi, had been reported missing in action there in July 1944. On September 8, 1944, Edith wrote Helmut a letter and placed it on a crystal bowl in her bedroom for mailing the next day. In the morning, a noise woke her up. As she later recalled,

It was like someone threw a rock through my window. I jumped up and saw my crystal bowl I had placed the letter on, was broken. The crystal fragments had formed a heart and a cross. When my father saw the fragments, he said to me: “I am sorry, my child, but I have to tell you, your fiancé was killed this morning. He did this to let you know he was dying.”

As the Births had feared, Helmut Kinder was reported missing in action in Latvia on September 9, 1944.[11] A “missing in action” notice represented a particular hardship for a soldier’s family, which Edith explained in her autobiography years later:

It was very hard to hear that one of your loved ones [was] killed in action, but it [was] almost even harder to read that he [was] missing in action. . . . You never knew how they died. Nephi was such a special fine young man. How did he die? Was he shot? Was he taken prisoner? Did he die of starvation as so many did in the Russian prisoner of war camps? Just missing in action, that was hard to take.[12]

Brigitte Birth (born 1935) recalled the heartbreak her mother suffered when Nephi was reported missing. “The first prayer I ever said beside the Lord’s Prayer was that my mother would finally stop crying.” As it happened, comfort came in a most unexpected way. According to Brigitte, her mother woke up one morning and told her elder daughters that Nephi had visited her during the night to say that he was, in fact, dead. Then she knew that all was right and that he would not be coming home.

A few weeks before the Allied landing in Normandy on June 6, 1944, Walter Kindt had a significant spiritual experience in France, a reminder that even (or especially) in wartime, there is time for reflection about one’s spiritual condition:

One Sunday morning, I prayed in the woods, asking my Heavenly Father to help me find a way to increase my faith and testimony and to always have His Holy Spirit. I was then told by a great impression of the Sprit, “Read the Book of Mormon.” Immediately I sent a letter to my parents asking them to send me a copy of the book, and they, of course, sent it to me at once.

After the Normandy invasion, Walter Kindt’s unit retreated steadily into the interior of France. As a member of the signal corps, he always had access to automobile transportation and quickly learned survival tactics which he used when attacked by Allied fighter planes: he tried to hide the car underneath a tree to stay out of sight and then used smoke bombs to trick the pilots into assuming that his car had been hit and damaged.

In his new assignment in Berlin, Hans Kindt was dangerously close to participation in a plot to assassinate Adolf Hitler on July 20, 1944. Hans’s commanding officer had conspired to have his troops capture and hold in house arrest certain high-ranking officers in Berlin while other conspirators took over the national army headquarters and the radio stations. Hans and his comrades were told that SS troops were planning a rebellion against Hitler and that Hans and his unit would be instrumental in saving Germany’s Führer.

Walter Kindt (right) with his comrades in France (W. Kindt)

Walter Kindt (right) with his comrades in France (W. Kindt)

The truth was quite the opposite. The plan was to have Hans’s unit assist in killing troops loyal to Hitler. By some quirk of fate, the bomb left in a conference room in Rastenburg, East Prussia, only superficially injured Hitler; the conspiring generals (including Hans’s commander) were rounded up and executed. Hans and his comrades were never ordered to carry out the plan for which they were trained. Had it come to that, he too might have been executed for treason.

Back home in Schneidemühl, Hans’s sister, Sigrid Kindt (born 1928), turned sixteen and was called to serve in the Pflichtjahr program. Her first assignment was on a farm. “They fed us as if we were in the army,” she wrote of the experience. Up at 4:00 a.m., they were marched every day to work, “singing as we marched.” It was not long before the work became military in nature—digging defensive positions for the German army. Due to the famous sandy soil of Prussia, the digging was relatively easy. However, life in the camp was not pleasant because, like soldiers, the young women were plagued by lice.[13]

In the fall of 1944, Fritz Birth was drafted. A veteran of the Great War, he was deaf in one ear and had hoped to be spared another tour of duty at his age (fifty-one) in order to stay at home with his wife and his nine surviving children.

“I remember watching my mother keep very careful records every night of the food ration stamps she collected during the day [in her grocery store],” recalled Brigitte. “She sent the records to city hall, and the distribution of food was organized very well.” Sister Birth was so concerned about the ration stamp audit that she even took some of the stamps with her when she fled Schneidemühl in 1945.[14] Initially she did not wish to flee, but her daughters were finally able to convince her of this necessity. Sister Birth left in January 1945 with her five youngest children and was able to reach Dresden safely by train. They were taken in by a family in the southwest suburb named Dölzschen.[15]

In their parents’ and brothers’ absence, Irmgard took over the operation of the glass shop and Christel and Edith took over the grocery store. Edith recalled, “We thought we would be safe for a while. We never were so wrong.” Packing some belongings onto two children’s sleds, the girls joined the throngs of refugees leaving the city on January 26 while the enemy artillery thundered close by. Edith later wrote of the painful separation:

We [had grown] up here, and it was a terrible feeling to leave everything behind. Everything in this home had a meaning to us. We loved this place, where we used to sing, play music and games, and had our harmonious family life. We loved our neighbors, our friends, and we loved our LDS branch in town. . . . We left with the hope someday to return.[16]

As many as three thousand Latter-day Saints shared Edith’s emotions as they left eastern Germany.

The Birth home on the outskirts of Schneidemühl. Sister Birth operated a grocery store in a room on the side of the house. (S. Dunbar)

The Birth home on the outskirts of Schneidemühl. Sister Birth operated a grocery store in a room on the side of the house. (S. Dunbar)

What had usually been a trip of three hours to Berlin became one of eight days and nights. The Birth girls and Wilford Kindt (younger brother of Hans and Walter) rode in a freight car devoid of supplies or amenities. From Berlin, the Births found another train headed south to Dresden, where they located their mother. Just a few days later, they watched from the Dölzschen suburb as downtown Dresden was reduced to rubble in the firebombing of February 13–14, 1945.[17]

Sigrid Kindt, then 16, was released from government service in November 1944 when the winter frost and ice set in, and she returned home to Schneidemühl. Very soon thereafter, she began to suffer from odd physical maladies that may have been related to overproductive glands. “I had horrible dreams, was skeptical of everything, and had spasms in my left arm. They gave me iodine and some kind of nerve medication.” At one point, a physician conducted a lumbar puncture “with a bent needle.” No results were reported.

From the summer of 1944, Hans Kindt lived near the Olympic Village in Berlin’s Charlottenburg district. He worked there as a tailor until January 1945, when he experienced the confusion of the fall of the Third Reich. Sent to fight the Soviets near Meseritz (just thirty miles east of the Oder River), he found chaos at an Eastern Front that was fast disintegrating. Under threat of death if he appeared to any fanatical military police to be retreating or deserting, Hans managed to keep out of harm’s way by pretending to deliver messages toward the rear. Eventually, he was sent back to Berlin, then to the west to oppose the oncoming American army.

When it came time to flee Schneidemühl in January 1945, Wilford Kindt went to the hospital to pick up his sister, Sigrid, who was still suffering from her unexplained illness. He took her to Fritz Birth, who gave her a priesthood blessing that healed her immediately. The two young people then went to the railroad station, where a Nazi Party leader stopped Wilford (who was then fifteen but looked much older) and ordered him to stay in the city to defend it from the Soviet invaders. Fortunately Wilford was able to find his Birth cousins, and they walked to nearby Lebehnke, where they boarded a train for Dresden.

Maria Kindt and her children made their way by train across northern Germany with several friends, and by early February they arrived in Tremsbüttel near Hamburg. They were quartered one by one in various farm homes and looked forward to the day when they could live together again.

Ruth Gärtner and her mother had visited Ruth’s sister near the Baltic Sea and returned home to Schneidemühl on the very day the last civilians left the town by train. In the confusion of a city in preinvasion panic, the last train departed before the Gärtners learned that they needed to leave with it; they were trapped in the city with no way out. They went to church that next Sunday and were disappointed to find that they were the only ones there. According to Ruth, German defenders fought valiantly for several weeks to save the city. During the fighting, her family stayed in a formidable air-raid bunker. One day, a Soviet soldier opened the door, and all occupants of the bunker were ordered out.

The invaders burned down most of the houses in the city center while searching for German defenders. However, civilians were also endangered during and after the conquest of the city. At one point, Ruth was lined up with seven other women:

There were eight of us ladies. And I was standing here in the middle and two [soldiers] were standing there, pointing their rifles at us. I just prayed and said, “Dear Lord, please let me be the first one to die,” and the minute I said that, I was looking to see if anyone had fallen yet. That same minute I finished my prayer, the bayonets went down, [the soldiers] turned around and walked off. . . . I didn’t want to see anyone else die. I wanted to be the first one, but [Heavenly Father] let me live.

Friedrich Birth with his wife and eleven children. The two sons in the back row, Gerhard and Nephi, were both killed in Russia. (W. Kindt)

Friedrich Birth with his wife and eleven children. The two sons in the back row, Gerhard and Nephi, were both killed in Russia. (W. Kindt)

The war in Schneidemühl ended in late February when the Red Army arrived, but a new phase of challenges and suffering began. The Gärtner women were impressed into clean-up crews, clearing rubble from streets and helping the conquerors systematically take valuables from private homes. By an odd stroke of fate, they found themselves one day in the rooms at Gartenstrasse 31, where the Schneidemühl Branch had held meetings for several years. According to Ruth,

I think [the Russians] kept all the chairs. There were loose chairs that we sat on. There was an organ there, too. They goofed around on the organ; they didn’t know how to play it anyway. They told us to pile the songbooks and other books in the street and burn them. They told us to take the big picture of the prophet Joseph Smith off the wall and put it in the fire. . . . I couldn’t throw that picture in; it was precious to me. . . . So I broke the glass, and I took the picture out and put the frame in the fire. I rolled the picture up and set it behind the door. I don’t know if anybody later on threw it in the fire or not. When the Russians began to get drunk on their vodka, we left the scene.

Soon after the destruction of the city of Dresden, Sister Emma Birth decided to seek refuge in a smaller, safer location. Her daughter, Edith, contacted her former mission companion, Gretel Dzierzon, who lived in Geyersdorf in the Annaberg-Buchholz Branch near the Czechoslovakian border. In response to Gretel’s invitation, the Births headed south, arriving by train two days later. There they were taken in by gracious hosts and quickly fell in love with the people and the region. Nevertheless, even in such an isolated region, fighter planes menaced the civilians, and Edith recalled being in danger every day of the week:

When we walked to church . . . on Sundays, we had to watch out and take shelter, when airplanes attacked. Seeking shelter meant falling to the ground in our Sunday clothing and not moving. [It was] a miracle no one of us was hurt.[18]

Brigitte Birth was only nine years old at the time, but she was personally offended when dive-bombers attacked civilians:

I remember hearing those [planes,] and I knew that the best idea was totally falling down on the ground and hiding in the flowers as much as I could. I almost had tears in my eyes because I said, “I didn’t do anything to that fellow up there.” I just didn’t.

By early 1945, Walter Kindt’s unit had retreated from France to Germany, and he drove his car across the Rhine River bridge at Cologne just before the bridge collapsed. Days later, the members of the unit were nearly surrounded by the advancing Americans. At the last minute, Walter managed to send a letter to his father in Yugoslavia and another to his brother, Hans, on the Eastern Front. He informed them that his mother had arrived in Tremsbüttel, northeast of Hamburg.

On April 15, 1945, Walter’s commander disbanded the unit, and Walter joined eleven comrades for a long trek to the north, his goal being a reunion with his family in Tremsbüttel. They traveled by night, using the North Star as their guide, then slept in hiding by day. The war had not yet ended. As they moved north, they traded their uniforms for civilian clothing at the homes of farmers. Although they went without food for several days, they were usually fortunate to receive food from sympathetic countrymen as they traveled. On May 1, they entered the large city of Hanover and witnessed the traditional celebration then observed by the victors. Walter was disturbed by his status: “Just the day before, we, the men in the army, were the heroes of the Fatherland—today we felt like criminals in hiding.”

While stationed in and near Berlin, Hans Kindt was occasionally able to attend Church events. This was still the case as the end of the war approached. Regarding one conference, he wrote the following:

I will never forget the last mission conference I attended as a soldier in Berlin. The people would come with a great outpouring of love for the gospel. They had lost their homes, some of them their loved ones, their possessions—but not their testimonies. We all knew that this would be the last time we would meet, and soon the war will come to an end, and deliverance was on its way. In defeat, and in all our suffering, we as LDS rejoiced, for it meant for us that our church [would] survive.[19]

By April 1945, Hans Kindt was in action south of the city of Berlin. At one point, a young soldier without a rifle was accused of desertion, and the officer in charge ordered that he be shot. Hans was the only soldier present who could to carry out the execution order. While the young man cowered by a tree and the officer paced back and forth, “I had to make a decision,” recalled Hans years later:

I would not do it. I could not do it. My life, my upbringing, my testimony had prepared me for this moment, and I was ready to suffer the consequences. I firmly believe that in coming to this decision, standing firm in my conviction, that the Lord blessed me when the officer had a change of heart and let him go.

In early May, Hans was told to round up as much food as he could in anticipation of being taken prisoner. He was fortunate to surrender to the Americans on May 8, 1945—the day the war in Europe ended. POW Hans Kindt worked for his captors as a tailor and gained the favor of several officers. Hans was soon transferred to a British POW camp. At one point, he was suspected of having been a soldier in the SS and was intensely interrogated. He even spent a few days in a regular prison but eventually fended off the accusations and was returned to the POW camp. He managed to secure a release as early as July 1945 and rode a bicycle nearly 150 miles to Tremsbüttel to join his family.

The Wolff family once lived in this building on the Kleine Kirchenstrasse in Schneidemühl. (W. Kindt)

The Wolff family once lived in this building on the Kleine Kirchenstrasse in Schneidemühl. (W. Kindt)

During the six weeks of his trek northward, Walter Kindt saw his companions go their various ways one by one. Along the way, they were twice stopped by American military police but not detained. Fortunately, it did not rain once during that time. Only one friend, Hans Gaedt, was still with Walter when he reached Hamburg, 250 miles from the starting point of their trek. The two found a man who took them across the Elbe River into town, and they continued northeast to Tremsbüttel, arriving two weeks after the end of the war.

Walter was thrilled to be able to attend church again—the first time was in a private home in the Hamburg suburb of Wandsbek. His account reflects the feelings of the occasion:

I will never forget this day. There I stood. . . . I had lost my home, all my belongings, my beautiful bank account, my friend, my job, and my hometown. I had even lost the war. . . . So at this sacrament meeting at the cottage, my first church gathering for long years, I felt the spirit of the Lord as I had never ever felt it before. I was facing a seemingly impossible situation, starting over with my life. Yet, I rejoiced in God. I prayed and promised my Heavenly father that I would do whatever was necessary to have this power of the Holy Ghost—this wonderful peace I felt at this moment on this day—all the days of my life.

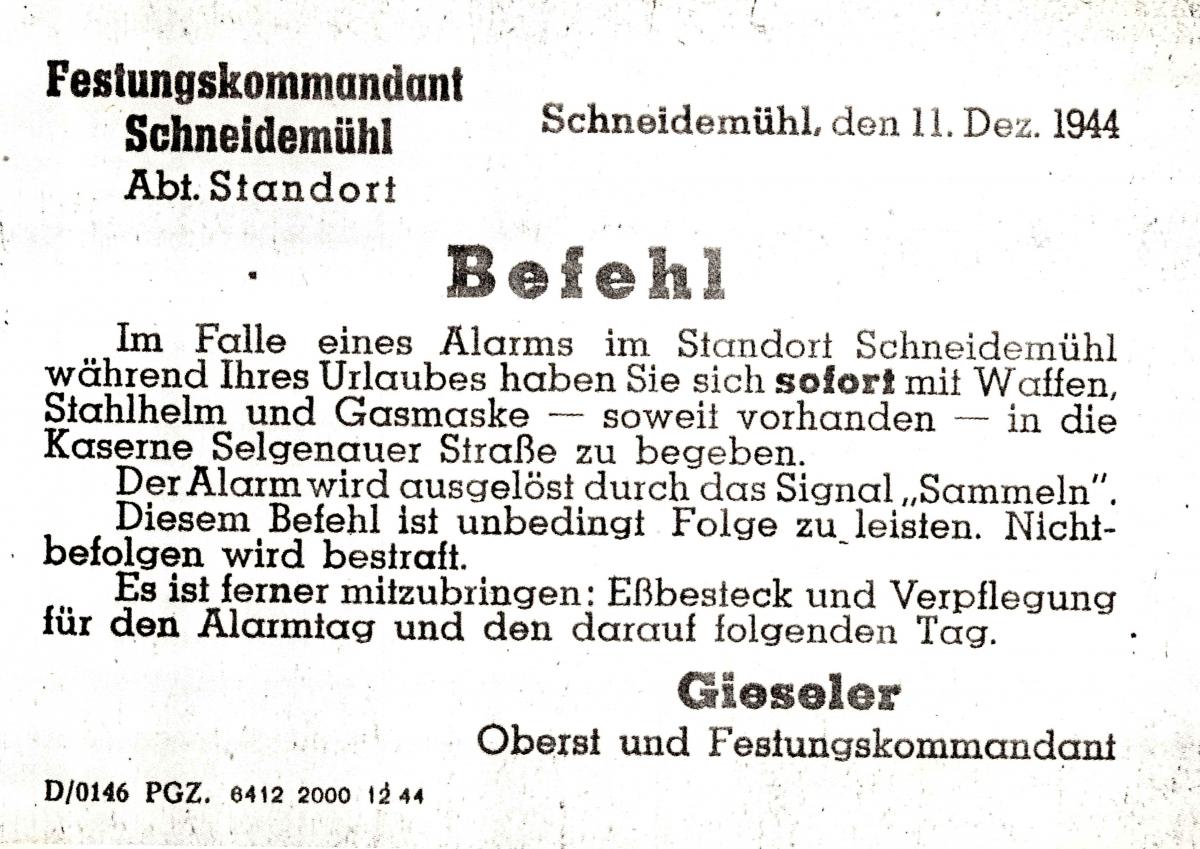

These instructions for emergency mobilization were issued to soldiers on leave in Schneidemühl in December 1944: “Should an alarm be sounded in Schneidemühl during your furlough, you are to report immediately at the Selgenauer Street army post with weapons, helmet and gas mask—if those are readily available.” (W. Kindt)

These instructions for emergency mobilization were issued to soldiers on leave in Schneidemühl in December 1944: “Should an alarm be sounded in Schneidemühl during your furlough, you are to report immediately at the Selgenauer Street army post with weapons, helmet and gas mask—if those are readily available.” (W. Kindt)

Of the surviving Births, only father Fritz was not in Annaberg-Buchholz when the war ended on May 8, 1945. Wilford Kindt received a letter from a friend indicating that Fritz Birth had been killed in the fighting near Schneidemühl. He informed the Birth girls, who dared not tell their mother. However, Sister Birth sensed from her daughters that something was amiss and learned the secret by reading Edith’s diary. Sister Birth refused to give up hope and took to fasting every Friday that her husband might still be alive.[20]

In July 1945, Emma Birth and several of her children accepted an invitation to join the large colony of LDS refugees on the Fritz Lehnig property in Cottbus. A month later, Margaretha Birth was ill with what some people thought was typhoid fever. From her sick bed, she told her brother, Werner, “Go downstairs and open the gate. Father is there.” They could not see the gate from her bed, so Werner did not go. She told him again, and once more he did not carry out her request. After the third time, Werner went downstairs and found his father standing by the gate.

Fritz Birth had been released from a Soviet POW camp and located the family with the help of the LDS mission office in Berlin. Edith recalled the unexpected, astonishing reunion:

My mother and the children that were with my mother were excited to see our father home. My mother’s feelings had not betrayed her! She knew all the time her husband, our father, was alive! It was a great reunion. . . . He had lost his right arm and was thin and old looking but full of enthusiasm and full of plans to start over again.[21]

On January 27, 1945, Anna Riewe and her five children were evacuated from Schneidemühl and transported to the town of Stralsund near the Baltic Sea. When the Red Army entered the city of Stralsund in the first week of May 1945, Anna and her children were hiding in a small apartment. While enemy soldiers scoured the city for women and girls, Sister Rieve found a secret door into an attic space, where she could hide her eldest two daughters. “During the night, the screaming of the women and the girls was terrible; we could hear it from our attic room,” recalled Esther years later.

Toward the end of May, Sister Rieve was told that if she expected to receive food ration stamps, she would have to leave Stralsund and return east to her home in Schneidemühl. When she arrived, she found that her apartment had been taken over by a Polish family. Her father had lost his large farm and his many horses and cows. The town had suffered extensive damage. “We didn’t like what we saw,” recalled daughter Esther. “The Russians and Poles were competing for the spoils.”

The Rieve family spent the summer months of 1945 in temporary housing, while Anna and her elder daughters were assigned to labor crews under Soviet supervision. Every night they were escorted under guard back to their homes, where they hid from potential molestation and brutality. It was a tense existence in a town that was no longer their home.

In August, Anna Rieve was allowed to leave Schneidemühl with her children. A military train transported them to the town of Burg, west of Berlin near Magdeburg. Always on the lookout for members of the Church, Sister Rieve eventually located other Latter-day Saints, and they began to hold meetings in Magdeburg. Her husband, Richard, was fortunate to be united with his family in Burg before the year was out.

Looking back on the end of the war, Esther Rieve recalled being in grave danger at least once. While traveling by train one day, she was pursued by a drunken enemy soldier who apparently had a venereal disease, which possibly meant both momentary and lasting torture for Esther. He chased her through the station, and for a few moments she escaped him by hiding under a pile of refugee belongings at a railroad station. As the train began to leave the station, she emerged from her hiding place and ran for the train, looking for a place to jump on. “My mother thought that I was going to throw myself in front of the train, but I didn’t have that in mind.” She was very blessed to avoid being assaulted.

Walter Kindt standing at the entry to the wartime church meeting rooms at Gartenstrasse 31 in 1999 (W. Kindt)

Walter Kindt standing at the entry to the wartime church meeting rooms at Gartenstrasse 31 in 1999 (W. Kindt)

The Gärtners were able to leave Schneidemühl in October 1945. The new Polish government had informed them that they would have to become Polish citizens if they wished to stay. They corresponded with the LDS mission office in Berlin and were instructed to travel to Barth (on the Baltic Sea north of Berlin), where three surviving Latter-day Saints would welcome them. Initially, the Gärtners had no money to purchase railroad tickets, but one day they found some paper money lying in the streets, discarded by other Germans who found that their money could not be used in local stores. With that money, they bought the tickets. They arrived at the home of the in-laws of Ruth’s sister, bringing with them only the clothes they were wearing and a 1941 Church hymnal.

Regarding her experience as a Latter-day Saint during the horrific last days of the war and the Soviet invasion, Ruth Gärtner later offered this explanation:

It was like being in a dream world. You really didn’t know if you were alive or if you were dead. You felt kind of nauseous, kind of numb; you didn’t know what was going to happen the next minute. For what we went through after the Russians came in, it was unbelievable. And I gained my testimony there. But still you sometimes ask yourself, “Why did this happen?”

Ruth had been engaged to Siegfried Jeske of the Driesen Branch since 1944. She lost track of him for two years before learning that he had survived the war. He was released from a Soviet POW camp in 1949, and they were married shortly thereafter.

Looking back on his years in the Wehrmacht, Hans Kindt recalled attending church only when on leave—there were no LDS meetings at the front. His father had given him a small New Testament that he took with him everywhere he went. He also tried to have religious conversations with other soldiers, but such occasions were not common. Speaking for himself and Walter, he said that despite their isolation from other Latter-day Saints, “I think we had a good upbringing that stayed with us. We would never even doubt anything [about the Church].”

By the fall of 1946, all surviving members of the Schneidemühl Branch had left the area and resettled in what remained of Germany. The once strong and vibrant branch disappeared into history.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Schneidemühl Branch did not survive World War II:

Gerhard Fritz Birth b. Zechendorf, Deutsch Krone, Westpreussen, Preussen 5 May 1918; son of Friedrich Martin Birth and Emma Pauline Hedwig Fritz; bp. 27 Feb 1927; ord. teacher; ord. priest, 15 May 193—; m. Tilsit, Ostpreussen, Preussen 11 Feb 1942, Rita Helga Meiszus; artilleryman; k. in battle Ssytschewo, Staraja, Russia 1 Apr 1942 (H. Meiszus Birth Meyer; LDS Ordination Certificate; www.volksbund.de; IGI; AF)

Nephi Albert Ferdinand Birth b. Schneidemühl, Posen, Preussen 6 Apr 1925; son of Friedrich Martin Birth and Emma Hedwig Pauline Fritz; bp. 9 May 1934; d. Russia 16 Jul 1944 (H. Meiszus Birth Meyer)

Friedrich Julius Preuss b. Norkitten, Insterburg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 28 Jul 1851; son of Gottlieb Preuss and Charlotte Laubichler; bp. 14 Aug 1920; ord. elder 1930; m. 7 Oct 1880, Ottilie Julianne Augusta Vogel; d. Schneidemühl, Pommern, Preussen 18 Apr 1940 (Sonntagsstern, no. 17, 26 May 1940 n. p.; IGI)

Alfred Heinrich Wilhelm Ross b. Schneidemühl, Posen, Preussen 15 Feb 1913; son of Adolf Wilhelm Ross and Anna Marie Wilhelmine Klingenhage; bp. 27 Mar 1922; m. Stargard, Pommern, Preussen 8 Apr 1938, Ilse Herta Marta Moeser; infantryman; d. near Obergänserndorf, Austria 28 Feb 1945 or Apr 1945; bur. Oberwoelbling, Austria (Anni Bauer Schulz; www.volksbund.de; AF; IGI; PRF)

Ottilie Julianne Auguste Vogel b. Bovenwinkel, Danzig, Westpreussen, Preussen 22 Jan 1852; dau. of Alexander Vogel and Julianne Plaeger; m. 7 Oct 1880, Friedrich Julius Preuss; d. old age Schneidemühl, Pommern, Preussen 3 Dec 1939 (Sonntagsstern, no. 17, 26 May 1940 n. p.; IGI)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 8, East German Mission History.

[3] Hans Kindt, interview by the author, Greendale, Wisconsin, August 19, 2007.

[4] Ruth Gärtner Jeske Hadley, interview by the author, Ogden, Utah, March 9, 2007.

[5] See the Schneidemühl District chapter for extensive information on Johannes Kindt.

[6] Walter Kindt, autobiography (unpublished); private collection.

[7] Walter Kindt, interview by the author, Greendale, Wisconsin, August 19, 2007.

[8] Edith Gerda Birth Rohloff, Life Is a Gift from God, (unpublished history, about 2003), 19; private collection. See the chapter on the East German Mission for details about her missionary service and the destruction of the mission office.

[9] Werner Birth, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, July 19, 2007.

[10] Esther Rieve Vergin, interview by Rachel Gale, Salt Lake City, June 6, 2007.

[11] Rohloff, Life Is a Gift from God, 26–27.

[12] Ibid., 22.

[13] Sigrid Kindt, autobiography, (unpublished, about 1952); private collection.

[14] Brigitte Birth Foster, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, January 10, 2008.

[15] Rohloff, Life Is a Gift from God, 27–28.

[16] Ibid., 28–29.

[17] Ibid., 33.

[18] Rohloff, Life Is a Gift from God, 35.

[19] Hans Kindt, Story (unpublished personal history); private collection.

[20] Rohloff, Life Is a Gift from God, 36.

[21] Rohloff, Life Is a Gift from God, 40.