Nössige Branch, Dresden District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 268-74.

The small town of Nössige is located fifteen miles west-northwest of Dresden in Saxony. The branch of Latter-day Saints living in and near Nössige during World War II had come into being mainly due to Jakob Christeler, a native Swiss, who owned a small farm there. Brother Christeler’s children and grandchildren comprised the majority of the small branch. Other families joined the Church due to his missionary efforts as he sold dairy products in the towns around Nössige. According to Elsa Böhme (born 1922), “One day he visited my family, and they talked about the Church. [My family] later joined the Church.”[1]

Jakob Christeler was the “founding father” of the Nössige Branch. He disappeared in Dresden in 1946. (G. Rudolph)

Jakob Christeler was the “founding father” of the Nössige Branch. He disappeared in Dresden in 1946. (G. Rudolph)

The family of Arno Rudolph lived in Semmelsberg, four miles east of Nössige. Son Georg Rudolph (born 1926) recalled his family riding bicycles for forty-five minutes to Nössige to attend meetings held in a large room in the building in which Grandpa Christeler lived on a large farm.[2]

| Nössige Branch[3] | 1939 |

| Elders | 2 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 0 |

| Deacons | 6 |

| Other Adult Males | 3 |

| Adult Females | 14 |

| Male Children | 7 |

| Female Children | 0 |

| Total | 33 |

Another son, Jacob Rudolph (born 1930), added these details:

We came with our bicycles, and we left them [at the foot of the stairs.] There were steps that went up to the second floor. We came in the right where the kitchen was, and they had a little living room in there. It was a little home for the workers who worked on the farm.[4]

According to Jacob Rudolph, his family members coulda not be deterred from attending church on Sunday: “We went in bad weather, it made no difference. In the winter time we went on skis. But my parents still walked.”

Sunday meetings (both Sunday School and sacrament meeting) took place in the morning in this small branch. On occasion, as many as thirty persons were in attendance.

In the small town of Semmelsberg, the Rudolph children were not under great pressure to participate in Hitler Youth activities. Brother Rudolph simply explained to the group’s leaders that his children were busy attending church and did not have time for additional meetings.

Jakob Christeler had spent a year or so living in Salt Lake City during the mid-1930s. He had taken genealogical documents along and was able to do ordinances in the Salt Lake Temple for many of his ancestors. When he returned to Nössige before the war, he was one of the very few endowed Latter-day Saints living in Germany.[5]

In a small town, a foreign or unknown religious group could be a matter of interest to the police. Elsa Böhme remembered that government agents visited meetings on occasion:

“We knew that if there was a person we did not know [in the meeting], he was there to listen to what we had to say. They wanted to find out if we said anything against the government, but we didn’t, and they left us alone.”

Arno Rudolph and three of his four sons were eventually drafted into the German army. Brother Rudolph returned after just six months of duty in Czechoslovakia and was not required to serve again. “He was night blind,” explained his son, Jacob. Two of the Rudolph boys lost their lives—Walter was killed near Stalingrad, Russia, and Herbert died in an accident while building a bridge in France.

During the absence of so many of their young men, life went on for the Saints of the Nössige Branch. In 1941, Jacob Rudolph was baptized. He recalled the event: “I was baptized in a pond a little bit outside of Nössige. My grandfather [Jakob Christeler] baptized me.”

The Ludwig family had moved from Görlitz to Nössige shortly before the war, and Brother Kurt Ludwig soon became the branch president. His son, Herbert K. Ludwig, later wrote a long and very detailed account of his experiences in Hitler’s Germany. His preface included the assertion that one could live under National Socialism without being a part of it. For example, he and his father were convinced that Hitler was leading the country in the wrong direction—a direction not sanctioned by God.[6]

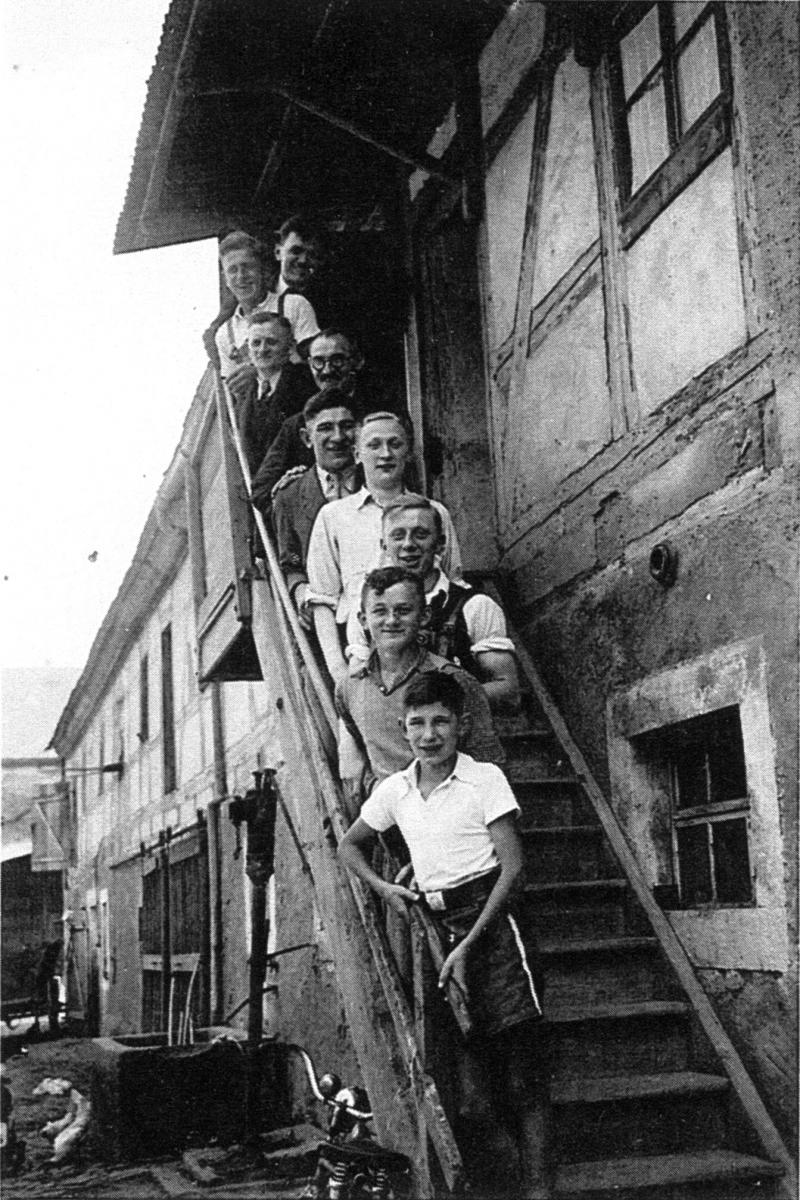

The Nössige Sunday School on an excursion in 1938 (G. Rudolph)

The Nössige Sunday School on an excursion in 1938 (G. Rudolph)

Kurt Ludwig was drafted into the army at the beginning of the war but was fortunate to be released after a short tour of duty. While he was in the Wehrmacht, his son, Herbert, was the only son at home to run the farm and was therefore exempt from military service until his father returned. When Herbert finally became a soldier, he had these feelings:

With all the pomp, music, parades, and talks, we finally did raise our hands and repeat the oath of loyalty and death; I felt helpless, forlorn! . . . What happened the next seven years in uniform to me I could fit in one sentence, “With the help of the Lord, I was preserved and returned home.”

Herbert Ludwig’s first year of duty was spent in the Soviet Union, where he was involved in the campaign to capture Moscow. Arriving in August of 1941, he experienced euphoric victories as the German army advanced quickly and steadily toward the Russian capital. However, as the German nation reveled in victories, what Herbert saw gave no cause for rejoicing. Here is his description of one battle:

Picture a mile-wide valley with a small river meandering through the pasture, the road running along it, forest on both sides from three to five hundred yards from the road, when two almost identical columns of vehicles met up with each other. Ours consisting of twin and four barrel automatic 20 millimeter guns, and theirs of heavy machine guns two and four barrel on trucks mounted, and when they had rolled up the full lengths, ours being on full-alarm stations. Some one on our side gave the order to fire, the Russians never had a chance—destruction was total, bodies strewn all over trying to escape, some hanging out the truck windows with the trucks still on fire, others with the doors open had just fallen out, others on the way to the woods mowed down. Some trucks trying to escape being caught in the cross fire still burning, ammunition exploding; some were ripped apart, and so were people; a total destruction.

As with so many other LDS soldiers, Herbert’s main concern was the possibility that he might be forced to take the life of another human being. On one occasion, he entered a dark house and found a Russian soldier lurking inside. They actually bumped into each other but neither had room to maneuver his rifle. Both raced for an exit and each threw a grenade back into the room. Apparently, neither grenade did any harm.

Herbert was constantly in combat engagements over the winter of 1941–42 and earned several medals for valor. He was the only member of his company not wounded or killed. However, on at least ten occasions, he came within inches of death or severe injury. In his written account, the phrase “Thank you, Lord!” marks such specific events, as he constantly recognized the hand of God in saving him (and he admitted that there were probably other times when he was not aware of having been endangered and spared).

The room in which the Nössige Branch held its meetings was reached via this staircase on the Christeler farm. (G. Rudolph)

The room in which the Nössige Branch held its meetings was reached via this staircase on the Christeler farm. (G. Rudolph)

In early 1942, Herbert was in close combat in a small Russian village and was chastised angrily by an officer who noticed that he was not firing his rifle. In response, Herbert took careful aim and shot about two feet above the heads of enemy soldiers. A few hours later, he and a comrade were hiding behind the corner of a cottage when an artillery shell tore through the roof just two feet above their heads. He later described the lesson he learned:

An impression, or you could say a voice, which let me know for the rest of my life—“just as you had aimed” [two feet higher]. . . . How can I forget such a lesson? . . . Do unto others as you would have them to do unto you.

During his eight months in Russia, Herbert had experienced the German advance to within a few miles of Moscow and the retreat that followed. He had gone through hell, suffering in ways he could barely bring himself to describe in writing. His sentiments were likely those of many Latter-day Saints in the uniforms of many nations at the time:

How do you stay sane? How do you keep integrity? How do you keep the Word of Wisdom? Or the commandments? Well, you just do; you make up your mind, and you don’t care about peer pressure or the opinion of your superiors. You will have plenty of opportunities to prove that you are loyal, dependable, physically better, and mentally more alert. You will be hated, admired, and commended for your guts; but above all you will walk ten feet taller (not stuck up) but for joy in knowing that you are sustained by the Lord. . . . How do you pray? As for me, very seldom aloud; but short and to the point. You feel closer than ever to Him.

After a short and relatively pleasant stay in France (interspersed with two furloughs at home), Herbert Ludwig was on his way to North Africa. He found it to be a totally different war featuring a clearly visible foe, very warm (but preferable) temperatures, and the presence of aircraft. Initially, Herbert and his comrades under the command of field marshal Erwin Rommel enjoyed clear victories against the British and the Americans, but the Allies eventually gained control of the region, and the German Afrika Korps was defeated and tens of thousands prisoners taken. Herbert was soon on his way to the United States and experienced what would be known as paradise for German prisoners fortunate to be taken there for the duration of the war. He was sent first to a camp in Ellis, Illinois, arriving there in the fall of 1942.

A wartime wedding is celebrated in the room used for worship services in the Christeler home. (G. Rudolph)

A wartime wedding is celebrated in the room used for worship services in the Christeler home. (G. Rudolph)

The camp in Ellis offered better conditions for German prisoners than they had seen for years as regular soldiers. Herbert Ludwig described the POWs as “birds in the golden cage.” He was fed well, treated with respect, and even paid for his labor (ten cents per hour by the Americans and three dollars per month from the German government through the Red Cross). He was allowed to write one card and one letter to Germany each month, and he received letters from home as well (with certain words blacked out by censors). He even received letters and packages from his Aunt Frances in Salt Lake City. An Uncle Herbert and an Uncle Willi actually visited him, as did Bishop Fred Busselburg from nearby Milwaukee, Wisconsin.

Georg Rudolph was in an apprenticeship program in Nössige when he was inducted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst on November 23, 1943. He served in that program near Warsaw, Poland. Just a week after returning to his family in Semmelsberg and to the Saints in Nössige, he was drafted into the Wehrmacht. It was already 1944, and he was sent to a unit near Paris. Georg was very fortunate in his assignment, as he explained:

I was trained to be a truck driver. There was an officer who always wanted to go to Paris, and he needed a driver, so he asked me, and I had many opportunities to see Paris. Oftentimes, as we drove through France, there were planes flying very low, and when they saw a car on the road, they started shooting at it. We tried to hide somewhere and often had to jump out of the car.

By early 1945, Georg was serving near Meissen, only a few miles from his hometown. His assignment had changed, and he was to monitor the artillery fire of the advancing Red Army; he and his comrades did so by placing microphones in the ground. As did thousands of other German soldiers facing the Soviets, Georg and his unit preferred to surrender to the Americans, so in April they cautiously made their way toward the Western Front, then only a few miles away. They were fortunate to be taken prisoner by the Americans not far from the city of Hannover.

As a common soldier with a very short tour of duty, Georg was a deacon in the Aaronic Priesthood. He never met another Latter-day Saint soldier while away from home, never had the opportunity to attend a Church meeting, and had no scriptures to read. The Lord blessed him, in that he was never in combat and thus never in serious danger. He was kept prisoner for only about six weeks and would have gone home right away, but this required that he cross the border from the British Occupation Zone into the Soviet Zone. He decided to work on a farm for a while and then joined with a friend from Leipzig. The two sneaked across the zonal border and made their way home. Georg Rudolph was able to celebrate Christmas 1945 with his family.

Sometime in 1946, Herbert Ludwig was sent from the POW camp in Illinois to New York City. He and his comrades were told that they were being released and shipped home. The transport ship passed the Statue of Liberty as it departed for France. Once there, the American promises of a quick trip home were violated. Herbert was sent to a camp in northwest France and forced to work in a coal mine. It was 1946 before he found a chance to escape and cross the border into Germany. With a comrade, he worked his way gradually north into the British Occupation Zone and from there across into the Soviet Zone. It was August 1946 when he finally caught sight of his home:

One hour from home! Slowly I start walking, I want it to be dark when I arrived, a surprise. . . . I make the final turn from the hill down from where I had seen my home for awhile; as I turn in, a small, white wooden fence comes up; it had not been there when I left. Now I can see our kitchen window with light in it. Oh, my Lord, I see more. I see Father, Mother, and sister, my head swirls, can I make it without being seen? Down the road, into the yard, up the outside flight of stairs, into the hall. I rap at the door, can’t stand the tension—“Come in,” is the call from Father. I can’t move. The door bursts open, my sister looks out, her mouth drops wide open. . . . “Oh, no, Herbert?!” . . . Father and Mother join in the embrace; do we need words? Happiness was never more true!!

One of the saddest events in the history of the Nössige Branch occurred in the summer of 1946. With his daughter, Jakob Christeler attended a district conference of the Latter-day Saints in Dresden. By then, he was an older man suffering from something similar to Alzheimer’s disease. After the meeting, he and his daughter waited for a streetcar. When it arrived, she boarded, carrying his coat with all of his personal papers (it was a very warm day). Suddenly the streetcar pulled away before he could get on. By the time she could return to that location, he was nowhere to be found. All efforts to locate him were in vain, and he would have been unable to identify himself. Jakob Christeler simply disappeared.

Elsa Böhme summed up the sad experience of the war and her reactions in these words: “What helped me throughout this horrible time of war was the knowledge that we are Heavenly Father’s children and that He loves us. He wants us to return to Him. I never doubted that He loves us although terrible things happened.”

In Memoriam

The following members of the Nössige Branch did not survive World War II:

Jakob Christeler b. Sengg, Bern, Switzerland 16 May 1866; son of Christian Christeler and Susanna Katarina Tritten; bp. 7 May 1904; endowment Salt Lake Temple 20 Oct 1937; m. Possendorf, Dresden, Sachsen 15 May 1892, Minna Anna Kuettner; 6 children; disappeared Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 7 May 1946 (IGI)

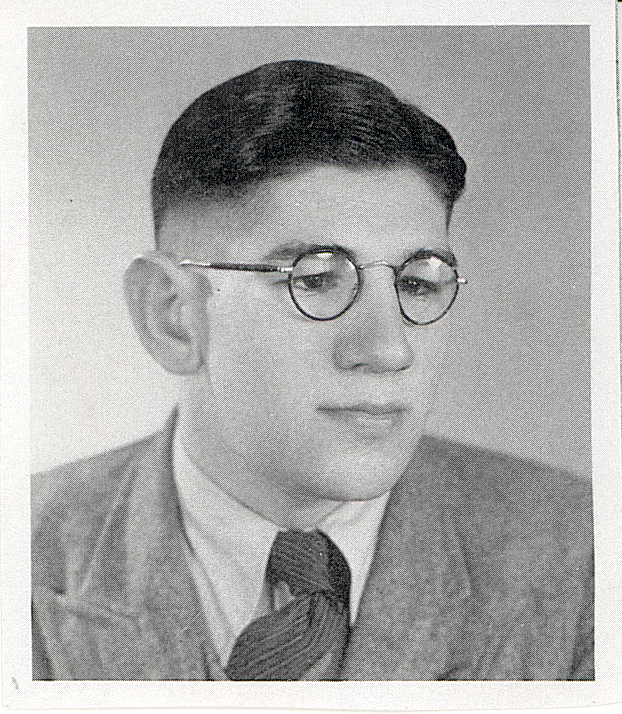

Arno Walter Rudolph (G. Rudolph)

Arno Walter Rudolph (G. Rudolph)

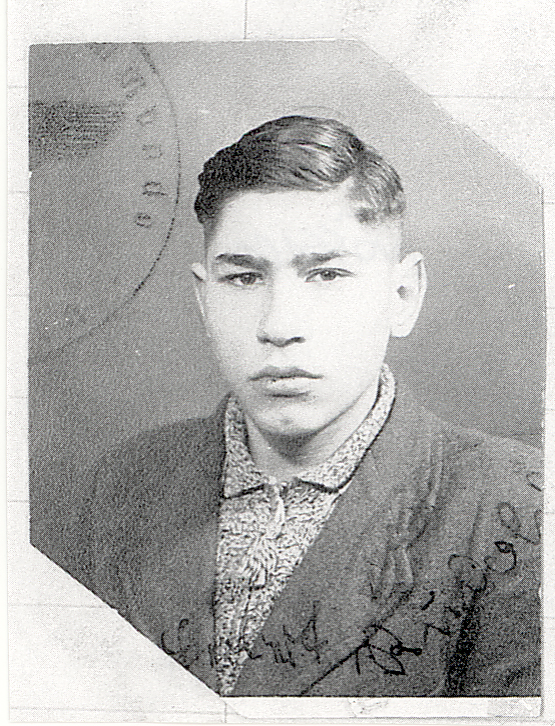

Alfred Herbert Rudolph b. Semmelsberg, Dresden, Sachsen 21 Jun 1923; son of Arno Arthur Rudolf and Rosa Frieda Christeler; bp. 9 May 1931; k. in battle France 20 Nov 1942 (George Rudolph; IGI)

Arno Walter Rudolph b. Nössige, Dresden, Sachsen 24 Apr 1916; son of Arno Arthur Rudolf and Rosa Frieda Christeler; bp. 26 Apr 1932; m. Krögis, Dresden, Sachsen 17 May 1941, Elli Liesbeth Beyer Ludwig; 1 child; k. near Stalingrad, Russia 31 Dec 1945 (George Rudolph; IGI)

Alfred Herbert Rudolph (G. Rudolph)

Alfred Herbert Rudolph (G. Rudolph)

Gottfried Walter Hommel b. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 12 Aug 1925; son of Johannes Bernhard Waechtler and Elisabeth Anna Hommel; bp. 5 Jul 1941; soldier; k. by mob near Nössige, Meissen, Sachsen 12 May 1945 (Fritz Waechtler; IGI)

Notes

[1] Elsa Böhme, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, February 8, 2008; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski, and an audio version of transcript of the interview is in the author’s collection.

[2] George Rudolph, interview by Michael Corley in German, Salt Lake City, January 17, 2008.

[3] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[4] Jacob Rudolph, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, July 26, 2007.

[5] At that time, the Salt Lake Temple was the closest temple to Germany.

[6] Herbert K. Ludwig, autobiography (unpublished); private collection.

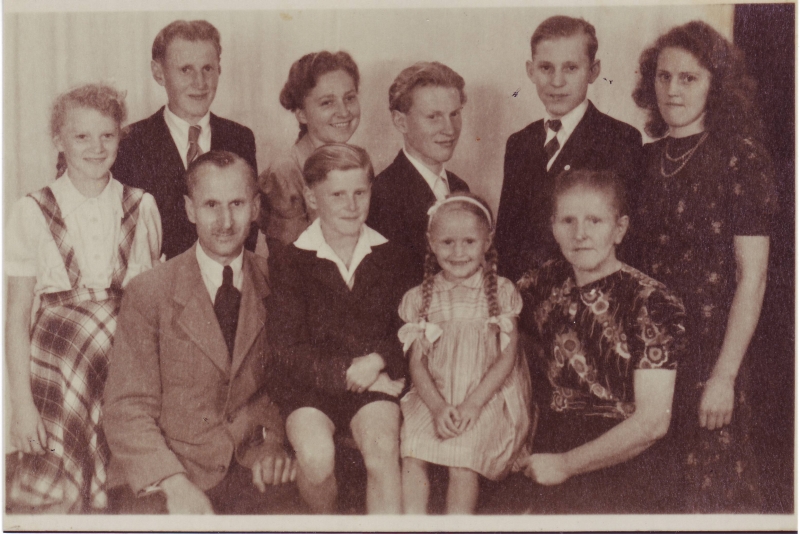

The family of Dresden district president Max Hegewald shortly after the war. One son had died as a soldier. (Hegewald)

The family of Dresden district president Max Hegewald shortly after the war. One son had died as a soldier. (Hegewald)