Neubrandenburg Branch, Rostock District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 360-72.

Just a few hundred feet south of the famous “Baker’s Wife” monument on the main street of the city of Neubrandenburg, the small but vibrant Neubrandenburg Branch met in rented rooms next to the post office. The address at the time was Adolf Hitler Strasse 12, and the rooms were on the main floor at this very central location in town.

| Neubrandenburg Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 4 |

| Priests | 5 |

| Teachers | 4 |

| Deacons | 4 |

| Other Adult Males | 21 |

| Adult Females | 49 |

| Male Children | 4 |

| Female Children | 4 |

| Total | 95 |

The city of Neubrandenburg in the historic province of Brandenburg, Prussia, is located fifty miles west of Stettin. It was decided in December 1938 that the Neubrandenburg Branch of the Stettin District should be shifted to the Rostock District (to the northwest).[2] The official justification for the change was that better railroad connections existed between Neubrandenburg and Rostock (even though the distance to Rostock was twelve miles greater). However, the very low population of the Rostock District may also have influenced the decision to move the branch with its ninety-five members to the Rostock District.

Frida Bauer (born 1922) later described the rooms in which the branch held its meetings:

It was a nice meeting room. It had a little podium with a pump organ. It was nice, in very good shape. It was almost too large for our branch. . . . We had three classrooms. A restroom was not right there. We had to go over to another building, the Hinterhaus. It was not very convenient, but we children were pretty disciplined. We went to the bathroom at home before going to church.[3]

Church activities in the East German Mission in the days leading up to World War II included cultural programs. For example, in the Neubrandenburg Branch, Erich Bernd gave a presentation on the Word of Wisdom on November 13, 1938, and one week later, an illustrated lecture entitled “The Life of Christ” was given by Adolf Klappert and Georg Daus. Attendance was sixty-four and fifty-seven persons, respectively.[4]

On Saturday and Sunday, March 11–12, 1939, the Rostock District spring conference was held in Neubrandenburg, with district president Günther Zühlsdorf presiding. Mission president Alfred C. Rees and Stettin district president Erich Berndt also attended. As reported in the mission history, “The [large] attendance of Saints and friends was very gratifying.”[5]

In early 1939, the branch president in Neubrandenburg was Karl E. Toebe, and his counselors were Ludwig Renter and Philipp Bauer.[6] Bruno Rohloff was the branch president in January 1941, when he visited the meetings of the Rostock Branch.[7] His son, Walter (born 1922), was the Sunday School president until he was drafted by the Wehrmacht in February 1942.

Members of the Neubrandenburg Branch in 1937 (A. Bauer Schulz)

Members of the Neubrandenburg Branch in 1937 (A. Bauer Schulz)

Sunday School began at 10:00 a.m., and sacrament meeting was held in the evening (“Children usually did not attend sacrament meeting,” recalled Frida Bauer). Priesthood and Relief Society groups met on Monday evenings, and MIA was held on Wednesdays. Primary meetings were held on Wednesdays after school.

Frida managed to avoid involvement in the Hitler Youth. Because her mother was already deceased, Frida’s official excuse was that she had to take care of the household. While other girls participated in the Jungvolk activities on Saturdays, Frida had to remain in school.[8] In one sense, attending school on Saturdays became a punishment for non-participation in the Party program.

Frida Bauer’s sister, Anni (born 1925), was encouraged by her father to avoid associating with the Hitler Youth. This caused her serious problems at school, but she found a way out by assisting in the association known as the Society for Germans in Foreign Nations. She invested substantial efforts on behalf of the thousands of Germans who were moved out of nations in Eastern Europe back to Germany, where they would be safe from persecution. Upon finishing her schooling, Anni was awarded a beautiful memorial book by the school’s principal. She later explained, “To me, this job was one of the greatest accomplishments in my life for a good cause, without being in the Hitler Youth.”[9]

The family of Paul and Ilse Meyer lived in Cammin, eleven miles south of the city. Daughter Waltraud (born 1920) recalled seeing only seven children in the Primary meetings. Attendance at church for her family was a bit complicated, as she later explained:

My family could not attend church regularly because the train schedule did not work out for us. We lived sixteen kilometers away from the branch. Today, it does not sound like much, but back then we had to take the horses to go to church, and we could not let them stand outside for that long while we were in the meeting.[10]

Members of the Neubrandenburg Branch on an outing in 1941 (A. Bauer Schulz)

Members of the Neubrandenburg Branch on an outing in 1941 (A. Bauer Schulz)

Waltraud Meyer’s brother, Kurt, was drafted soon after Germany invaded Poland in September 1939. Waltraud recalled her reaction to hearing that war had begun:

When the war started back then, I remember being kind of excited since we all thought that Germany would conquer the entire world. I could not understand why my father had to be careful about his political views or why he did not express them more often. I was nineteen years old when the war started and had no political knowledge about the war whatsoever.

Waltraud Meyer was inducted into the German Red Cross in 1940 and spent much of the war away from Cammin and the branch in Neubrandenburg. After a short stint in a local hospital, she was sent to Forst in Silesia, then to France.

Tragedy struck the family of Ernst and Ida Schulz just weeks after the war began. Vera Schulz (born 1917) later described the incident:

My father, Ernst Schulz, was a worker and also spent much time helping out at the airport in Trollenhagen near Neubrandenburg, where he died on 6 October 1939. . . . On that day, my father saw an airplane that was on the runway and was stopped by a large branch of a tree. He jumped over a ditch and wanted to remove that branch and although his colleagues warned him and shouted at him, they later said that he seemed to be drawn to do it. When he attempted to remove the branch, the pilot started the engines and the propeller started and hit my father.[11]

After the death of her father, Vera Schulz and her mother, Ida, worked at a munitions factory where the brother of branch president Bruno Rohloff was the head of personnel. Vera soon married and was the mother of three children by 1943.

Günter Streuling’s father was a member of the Church and also of the Nazi Party. According to Günter, “We had a picture of Hitler hanging on the wall, and a copy of Mein Kampf was tucked away in the closet.[12] The Hitler picture was a profile in black, and it hung over the door from my parents’ bedroom to the living room.”[13] Günter’s father was often at odds with the neighbors in their apartment building because most of them were communists. Fortunately, debates conducted in the stairway never became violent.

Young Günter Streuling (born 1935) could hardly wait to join the Jungvolk because the older boys seemed to be having such a great time. As he later explained:

I envied them, so I pushed my mother to let me join. I don’t know why she opposed that plan. Finally, she said yes, so I joined. I was accepted. My mom got me a shirt and sewed me some pants. After school on Wednesdays, we went to march and had weekend activities. They taught us not to smoke and to help old ladies across the street. I wore a knife on my belt but was never taught to use it.

During the first few years of the war, the Nazi Party confiscated the main branch meeting room at Adolf Hitler Strasse 12 for the use of the local Hitler Youth group. According to Walter Rohloff, “they left us only the three classrooms.”[14] The directory of the East German Mission shows the next meeting address as Pasewalkerstrasse 11 (the home of the Rohloff family) in January 1943—with the notation that meetings were not being held at that time. “We still met for Relief Society,” recalled Frida Bauer. “I know, because I was the secretary. But very few sisters came.”

While other Latter-day Saint women were required to take jobs in offices or industry during the war, Waltraud Meyer served in the Red Cross for nearly five years. “I did not have any problems working for the Red Cross,” she recalled,

[But] it was hard for me to see the wounded people because it always made me think about people I knew whom I could lose during the war or who could get hurt. . . . When I was in France, we worked in different shifts in the Red Cross. We started at eight in the morning, and sometimes things would not go as well, and we would have to work until eight the next morning. The normal shift ended late in the afternoon.

Waltraud found herself in hospitals in various larger cities during her work with the Red Cross. She attended Church meetings in Stettin and Berlin, for example, whenever she had the chance.

On several occasions in 1941, Walter Rohloff was approached by recruiting officers of the Waffen-SS. Each time, he lied to avoid their offers, telling them that he planned to join the air force. At the time, he enjoyed immunity from the draft, because he was employed in a critical war industry. However, by January 1942, Walter decided to volunteer for military service. He later explained this decision:

I wanted to go because none of my friends were home anymore. All had been drafted and had joined the armed forces. Some had died already in war action, and when I met the parents they asked me why I was still home. I was embarrassed and hated it. They probably thought I was a draft dodger. I was not afraid of going to war, even though I did not really understand what it meant.[15]

For Walter Rohloff, the question of religion had a genuine impact on his military career. Wehrmacht officials wanted to register him simply as Catholic or Protestant, but he indicated that he was a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, whereupon the entry “Jes.Chr.” was made. One officer asked him “What is that?” but there was no time for a discussion. Later, Walter pondered long and hard over the question, “What is that?” A few months later, a soldier asked him if he was a “Latter-day Saint” by conviction or simply because his parents were. These two events caused Walter a great deal of soul-searching, and he studied the scriptures intently to find an answer to those questions.[16]

Vera Schulz was not able to attend church very often during the war, but she was involved in several activities in the branch. For example, she remembered a wintry baptismal ceremony:

I can remember that we also had baptisms during the war, but I cannot tell who was baptized. I only know that there was one day when we baptized three people—it was a cold winter day, and they chopped a hole in the ice on the Tollensesee [Lake] and it was cold. We did not have to do baptisms in secret.

Vera remembered that while there were no air raids over Neubrandenburg, the alarms sounded as often as three times a week, and she had to take her children to the shelter in the basement. “We also packed a little suitcase for each of the girls, and although they could not carry them on their own, the suitcases stood in the corner prepared.”

Life in Neubrandenburg for Vera and her mother was tolerable through most of the war. Her husband was away in the Wehrmacht, but Vera’s existence was relatively free of privations. As she later explained, “We still had some heat, electricity, and water, and although we could only use a certain amount, we had enough. All in all, we did not have many wants when it came to food, water, or the standard of living in general.”

Shortly after completing her schooling, Anni Bauer moved to Stettin to serve her Pflichtjahr in the home of the wealthy family of Dr. Xaver Meyer. It was an “attractive and sophisticated home,” and she enjoyed the experience, but was soon quite overworked and became ill. Nevertheless, she was very much at home in the Stettin Branch. Having attended district conferences there in the 1930s, she knew most of the members. It was there that she became acquainted with young Juergen Schulz: “I certainly had a crush on him, ever since I met him.”

In 1942, Anni Bauer’s employment required that she move east to Schneidemühl. For nine months, she worked in a stressful environment that included harassment from the local Hitler Youth officials. She was so miserable that she became seriously ill and was bedridden for six weeks. She felt quite fortunate to find a physician to sign papers attesting to her maladies and allowing her to return to Stettin.[17]

While in the Wehrmacht during the second half of 1942, Walter Rohloff suffered from various illnesses, including nerve paralysis. In January 1943, he was released from a hospital and was given leave to spend two weeks at home. He later wrote of the condition of the Neubrandenburg Branch at the time: “Our little branch of the Church was almost non-existent. After discussing this with my parents, I visited the remaining members, and we had Sunday meetings at our home.”[18]

In 1943, Walter Rohloff was stationed in Gnesen in Poland. From there, he found a way to travel sixty-five miles to Schneidemühl to attend church. There he met the Birth family with their ten children. He felt so much at home there that he found many occasions to visit them again before February 1945. With time, he also fell in love with Edith Birth, one of several very attractive daughters in the family.[19] Later that year, Walter was enrolled in Officer Candidate School and learned early on that if he were unwilling to embrace National Socialist ideology (and deny his faith), he had little chance of successfully completing the program. By March 1944, this became a reality. He was returned to his unit without promotion and later learned what had been written about him in the Officer Candidate School (where his performance was better than most other participants): “Religious fanatic. Belonging to the Mormon sect. Politically not trustworthy.” He was proud to have defended his faith and did not regret not being promoted.[20]

On the Eastern Front in June 1944, Walter Rohloff was hit in the face by shrapnel. In the confusion caused by an enemy attack, he was nearly left behind in a hospital that was eventually surrounded by Soviet soldiers. At the last moment, he was rescued and taken west, then sent to a hospital in Kirchhain, Silesia. While there, he found a way to sneak out of the hospital to attend church in Cottbus, a few hours away by train; he was able to sneak back into the hospital in the evening before his absence was discovered. After surgery to remove the shrapnel from his forehead, he was assigned to a new unit and sent to the Western Front.[21]

During the fall of 1944, Walter was constantly under fire from the Americans who were approaching Germany’s western border. Decorated for valor with the Iron Cross, Second Class, he came very close to being killed when American tanks advanced toward his foxhole. As he later explained, “There was no help in sight. This was the end. I prayed. I always said my prayers, but this time it was different. It was a cry for help. I didn’t want to be run over by tanks.” As if by a miracle, a German howitzer was moved into position and quickly put two tanks out of action. The rest retreated, and Walter was saved. “A thanks went up to my Heavenly Father. That was a close call.”[22]

Due to his fine record of bravery under fire on the Western Front, Walter Rohloff was given leave from December 12 to January 3. While he was in Schneidemühl visiting Edith Birth, the German army launched its Ardennes Offensive, and the Battle of the Bulge was underway. By the time he returned to the front, nearly all of the soldiers serving with him had been killed or wounded. Just before he left Neubrandenburg, Walter had been admonished by his father to “stay close to the Lord” and to contact the mission office in Berlin, in order to find the family after the war.[23]

In early 1945, while attempting to cross the Rhine River to the east side and temporary safety, Walter Rohloff was rowing a small boat under fire from the west bank. Just yards from the east bank, he was hit by a bullet that penetrated his abdomen. Fortunately, he was transported to a nearby hospital and given the necessary medical treatment. Over the next few weeks, he was moved town-by-town east and north to Lüdenscheid, where he was taken prisoner by the advancing American army on April 13, 1945. His wound had not yet fully healed, but his condition was improving.[24]

By December 1944, it was clear that the Red Army’s advance toward the city of Neubrandenburg could not be halted. Frida Bauer recalled thinking to herself, “This is it! Where is God? We could not believe the government any longer. Hitler continued to speak [over the radio] until 30 January. He said we were going to win and we were going to have those new [‘miracle’] weapons. But we didn’t believe him.”[25]

In January 1945, Anni Bauer left Stettin to visit her fiancé, Juergen Schulz, in Thorn in West Prussia—close to the advancing Soviets. Her father had warned her against making the trip, but she went nevertheless. Arriving in Thorn just hours after Juergen was moved closer to the front, she had no option but to turn around and head for home. Unfortunately, the chaos of the refugee territory resulted in a three-week journey filled with terror and suffering. Anni had already endured several serious illnesses and surgeries during the previous three years and was no longer physically capable of making a trip of two hundred miles, some of it on foot. In temperatures near zero, with shoes falling apart and with little or nothing to eat, she found that the physical suffering led to emotional suffering: “I reached the point, where I really didn’t care, one way or another, whether I would be able to get out or not. I prayed to Heavenly Father to let me die without much suffering. I was very discouraged.” At one point in the exodus, she was shoved onto an open railroad car and watched infants die in the bitter cold as the train crept slowly westward. The train was attacked several times by enemy fighter planes and Anni could feel the discouragement growing:

A change in attitude overcame me—I turned very bitter. For the first time in my life I couldn’t pray. I couldn’t understand why Heavenly Father could let little, innocent babies and children suffer so much. . . . The exhaustion seemed to have killed everything in us. . . . Maybe my thoughts were so distorted because of cold, lack of sleep, hunger, and pain.[26]

Despite being so weak during the three-week trip that she fell unconscious more than once, Anni also had to endure several attempts by Polish men to assault her. She was successful in fending them off each time. She finally reached Stettin, found another train to Neubrandenburg, and dragged herself from the railroad station to the apartment of her sister, Wanda, who took her in and nursed her back to health. Anni was only nineteen years old at the time.[27]

As the danger of invasion seemed to intensify, the women of the Bauer family made preparations to flee Neubrandenburg. Frida recalled saving the fat from bacon for three months to spread on bread. She also began listening to the news broadcasts of the BBC “because German radio news came a day late and was not reliable. . . . This was really dangerous, and I had the sound really low and put a blanket over my head and the radio so nobody [else] could hear.”[28]

Frida’s father, Phillip Bauer, managed to return to Neubrandenburg from West Prussia just before Christmas 1944. Over the next three months, the situation became increasingly critical, especially since he not only had two young adult daughters at home but was responsible also for the twelve children of his three married daughters, Emmi, Wanda, and Marthel (all of the grandchildren being under the age of nine). He went to the forest one day to pray about what to do and came home to announce: “We are getting out of here—quickly!”

On about April 27, 1945, the Bauer family (seventeen persons in all) loaded a small Bollerwagen and headed westward out of town amid throngs of refugees. Everyone was looking to catch a ride on a truck, and the roads were filled with all kinds of vehicles—both civilian and military. By some miracle, a truck offered to take the whole family, with the exception of Frida and her sister, Anni, because they had bicycles.

Unfortunately, the girls were strangers to bicycles and found them very difficult to ride. Thus they basically pushed the vehicles down the road, using them at least to transport their meager supplies of food and clothing. They eventually reached Güstrow—about forty-five miles to the west. Luckily for them, the invaders, at the same time, were more interested in moving south toward Berlin.

At the age of ten, Günter Streuling could probably not understand why Nazi Germany was making war on the Jews. However, after one experience at the Neubrandenburg railroad station, he understood that some people were not treated well by the government:

In early 1945, we were asked to go to the train station to hand out food to refugees. One day I was on the platform, and a cattle train pulled in. I noticed that there was barbed wire over the airhole at the upper right. That looked strange. We heard movement inside, then suddenly faces appeared in the opening. . . . I thought that these people had done something really bad to be in that situation. They held out tin cans and said, “Wasser, Wasser!” We could easily reach the airhole, and we took the tin cans, filled them with water, and carried them back. [The prisoners] spilled most of it in the process. We kept doing that until the SS troops came running and pointed their rifles at us and yelled, “Get out of here!” The last thing I saw was the soldiers pounding their rifles against the sides of the cars, telling [the prisoners] to get away. The train came from the east and was headed west.[29]

Günter Streuling’s father was in the Luftwaffe, assigned to a hospital on the island of Sylt (off the west coast of the North Sea, in Schleswig-Holstein near the Danish border). He sent his wife a forged document authorizing her and their son to join him on Sylt. After an adventure-filled week of travel by train, by bicycle, and on foot, Günter and his mother arrived on the island. Although the island was very isolated, they were not free from the sights and sounds of the war. American and British airplanes were constantly flying overhead on their way to targets in Germany and back home. Günter recalled gruesome scenes: “On the way back [to England], the crippled [Allied] aircraft were shot at by our antiaircraft batteries. Several times, we found dead British airmen washing up onto the shore. That was really traumatic for a young [ten-year-old] boy.”

By the time Red Army soldiers were approaching Neubrandenburg, Waltraud Meyer was twenty-four years old, unmarried, and back at home in Cammin. The town of one hundred fifty inhabitants had swollen to twice its size as the local residents took in refugees from the east—family, friends, even strangers. When the enemy approached the town, Waltraud went into hiding (“because I expected something terrible to happen”) and was for a short time separated from her parents. When she returned, she was greeted with the news that her parents had taken their own lives in their home. This was a horrible experience, as she later explained:

At first, I wanted to go into our house [to see the bodies of my parents], but the neighbors told me not to. I walked back into the village and other people offered to let me stay in their home for the night because they did not want me to be alone. My parents were buried the same night. Following that experience, many others committed suicide also—even families with up to six children. It was a horrible time.

According to Waltraud Meyer, “I have to confess that I did not really have a testimony of the gospel when I was young. I followed my parents, and if they had been Protestant, I would have been the same also. My testimony grew during and after the war.” Waltraud escaped harm at the hands of the Soviet occupiers in Cammin and assisted her neighbors where she could. Her brother, Kurt, returned to Cammin in July 1945. He had been told when he arrived in a nearby town that his parents and Waltraud were dead, but fortunately he did not believe the reports and was happy to see his sister still alive. They eventually made their way west to Elmshorn (north of Hamburg) where they were again associated with the Church.

Vera Schulz and her children were still in Neubrandenburg, along with Vera’s mother and her sister, when the Soviets entered the city at the end of April. Overnight, the citizens were ordered to evacuate the town. This was a severe challenge to the women who had no men to support them. Vera later recalled the move:

I had a bike with a basket in the front, and my youngest daughter was in her stroller. My mother pushed the stroller, and we loaded as much as we could into the bags that we had on it. We walked to Podewall, near Trollenhagen [three miles north of town] and slept near a forest for one night. My mother was concerned that we would lose all the things that we left behind in our home in Neubrandenburg, so she asked me to go back and get some of the important things, like a coat for my brother. One morning, I went back and got a bed cover for my children so they would not be cold anymore and a coat for my brother. I stood outside and tried to fasten all the things onto my bike when the shooting began. The house next to us was hit and also the house I was standing in front of. Our windows burst and some splinters hit me. I could not ride my bike out of the city, so I just pushed it. When I was going back to where my family was, I met some [German] soldiers in civilian clothing who gave me a new bike and helped me.

Although hundreds of Latter-day Saint women later told of miraculous escapes from the conquerors, not all were spared the suffering associated with physical assault. Such was the case with Ida Schulz when the hiding place of the Schulz family was discovered by Red Army soldiers. As Vera recalled, “[The soldiers] took my mother away, and she kept her hands tightly around her handbag because she did not want to lose it. It was horrible to see what they did to her. When she came back, she did not talk to anyone for days.”

After a few days in the forest by Podewall, Vera and her family returned to their apartment in Neubrandenburg but found enemy soldiers living there. After a few weeks in an army barrack, they were allowed into their apartment again. They were sad to see what had happened in the interim, as Vera explained:

Lots of things were missing. Two things that I was very sad about having lost were the Book of Mormon and the Bible that Elder Kronemann, the missionary who baptized me, had given me for my baptism. The Russians did not even know how to read them, but they must have seen how nice they looked with the gold writing on it, so they took them away.

At one point on their flight westward, Frida and Anni Bauer slept overnight in an inn but learned the next morning that their bicycles had been stolen. After “a good cry,” they sat by the road again to hitchhike and were fortunate to have a troop of soldiers take them along. They eventually followed an older soldier toward Denmark, but they were turned away at the Kaiser Wilhelm Canal and headed south toward Hamburg when they heard that the war was over. They then headed for Saxony to a friend’s home but gave up the plan when it became evident that to live in the Soviet occupation zone in eastern Germany would not be a good thing. Shortly after the war ended on May 8, 1945, Frida and Anni joined other members of their family in the city of Celle near Hanover. All of her family had survived the war, with the exception of her soldier brother, Otto Bauer, who had been killed in Russia in 1941.

With his “thousand-year Reich” crumbling all around (only twelve years old at the time), Germany’s Führer, Adolf Hitler, committed suicide in his underground bunker in Berlin on April 30, 1945. Günter Streuling recalled that day:

One day the announcement came that the Führer was dead, that he had died when hit by artillery while directing the defense of Berlin. We went to school and sang the national anthem and also “Ich hatt’ einen Kameraden” (a favorite song when a soldier died). I remember crying and going home. After the war was over, we found out that it was a lie [and that he had actually killed himself].

Otto Krakow (born 1910) returned from the war in search of his mother in Neubrandenburg. Years later, he told of coming home on crutches, hoping to get his family to safety, and described conditions there: “Just as everything else was in a state of destruction and disorder, so was the Church in Neubrandenburg. The branch no longer existed; no responsible brethren were left.”[30]

By late 1945, Walter Rohloff had been moved through several POW camps and finally arrived in Belgium. By early 1946, he applied to work in a coal mine. As an officer, he was not required to do heavy labor but hoped to improve his condition with better food rations and the minimal wage paid for POW labor. He also learned that year that his mother had survived the war but that his father was a prisoner of the victors. While working in the coal mines at nearly two thousand feet below the surface, Walter was buried alive on two occasions but managed to escape. After several months, he and other German POWs went on strike due to the dangerous work conditions. His reward for the successful strike effort was the transfer to a farm.[31]

During his incarceration in Belgium, Walter was able to spend significant amounts of time studying the Doctrine and Covenants in preparation for serving as a missionary when he returned to Germany. He also found opportunities to discuss religion with military chaplains and other soldiers. His conduct among common Belgians was so correct that some of the locals tried to convince him to remain there and to marry. However, his thoughts were on his mother in Neubrandenburg and his father somewhere in the Soviet Union. Of course, his desire to go home increased over time, and he actually attempted an escape. While crossing a bridge into Germany, he was caught and returned to the POW camp. Following a term of light punishment, he went back to work on the farm.[32]

Looking back on her wartime experiences, Waltraud Meyer came to the following conclusions:

I was protected so well so many times. The Lord had his hand in my life and guided me. . . . There were so many moments when I thought that I could not make it. Other people around me had horrible things happen to them, but I often felt that a protecting hand was over me. I often felt like I should go a different way or another direction. There was no other way than to develop a stronger testimony. . . . I did not have only one angel who protected me, but at least a hundred.

Anni Bauer wrote the following comments regarding her wartime experiences:

After an inner struggle with myself, I regained my strong testimony of the love of our Heavenly Father. . . . The years of 1944–45 were the most difficult times of my life. But the knowledge of the gospel and the plan of eternal life and salvation truly gave me the strength to keep on going through those trying years.[33]

Juergen Schulz spent a year in Denmark after the war, recovering from serious wounds. Then he traveled to Celle to be reunited with Anni Bauer. They were married there in 1947.

In November 1947, Walter Rohloff was released as a POW in Belgium and made his way home. When he crossed the border into the Soviet occupation zone, he found conditions to be dismal and wondered if he should have remained in the American or British zones. Nevertheless, he was needed by his mother and the Neubrandenburg Branch and made it home in a few days. He surprised his mother with his arrival, as he later wrote: “She looked tired and a little worn out, but when she recognized me, her eyes lit up and she fell into my arms crying. I was a little clumsy. I was not used to taking my mother into my arms. I let her feel I love her and was glad to be home after all.” He also surprised her with a substantial supply of things she badly needed, such as shoes, yarn, and sweets.[34]

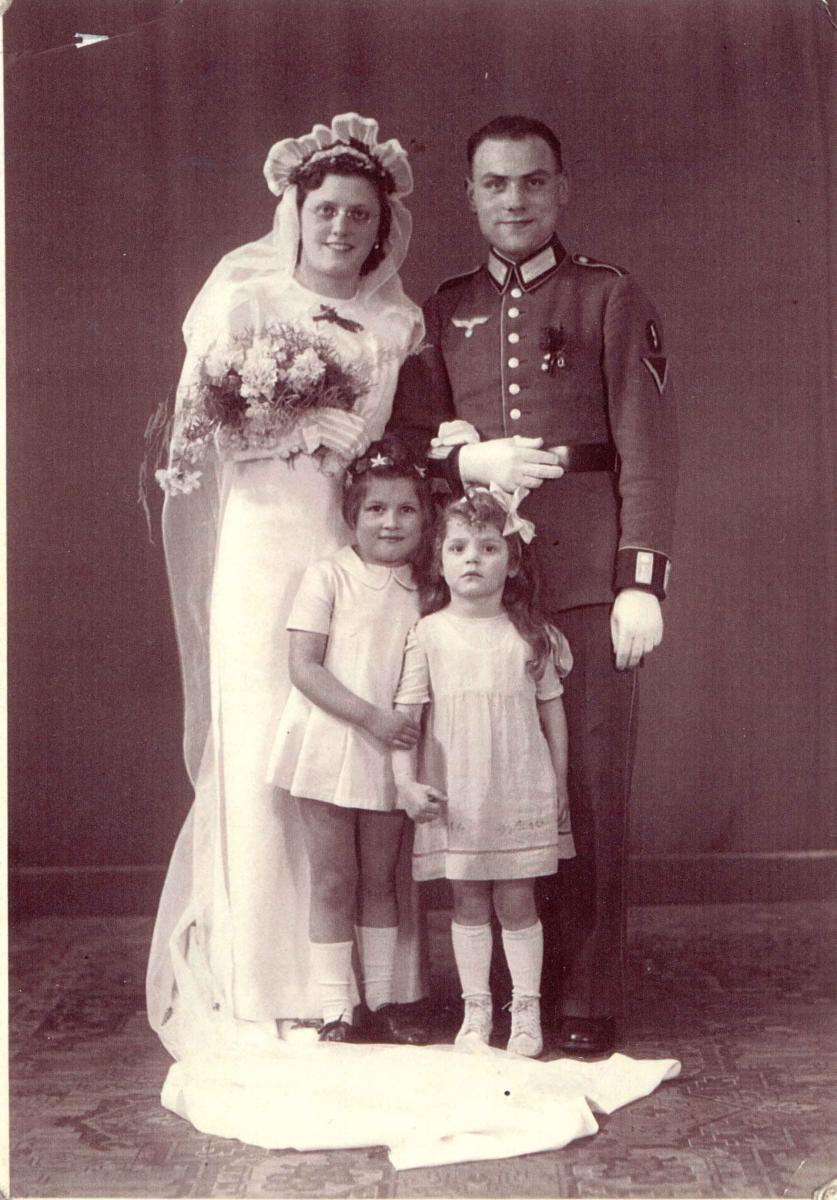

Otto Bauer and Vera Giehr were married in 1941. (A. Bauer Schulz)

Otto Bauer and Vera Giehr were married in 1941. (A. Bauer Schulz)

Seriously weakened by the departure and death of many of its members, the Neubrandenburg Branch barely survived the war. It would be several years before a strong branch would emerge there again.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Neubrandenburg Branch did not survive World War II:

Otto Bauer b. Biskopitz, Thorn, Westpreussen, Preussen 12 May 1918; son of Philipp Bauer and Luise Wilhelmine Kuhn; bp. 16 May 1931; m. Berlin, Preussen 10 Mar 1941; d. at WWII action Klin, Kalinin, Russia 15 Dec 1941 (IGI; AF)

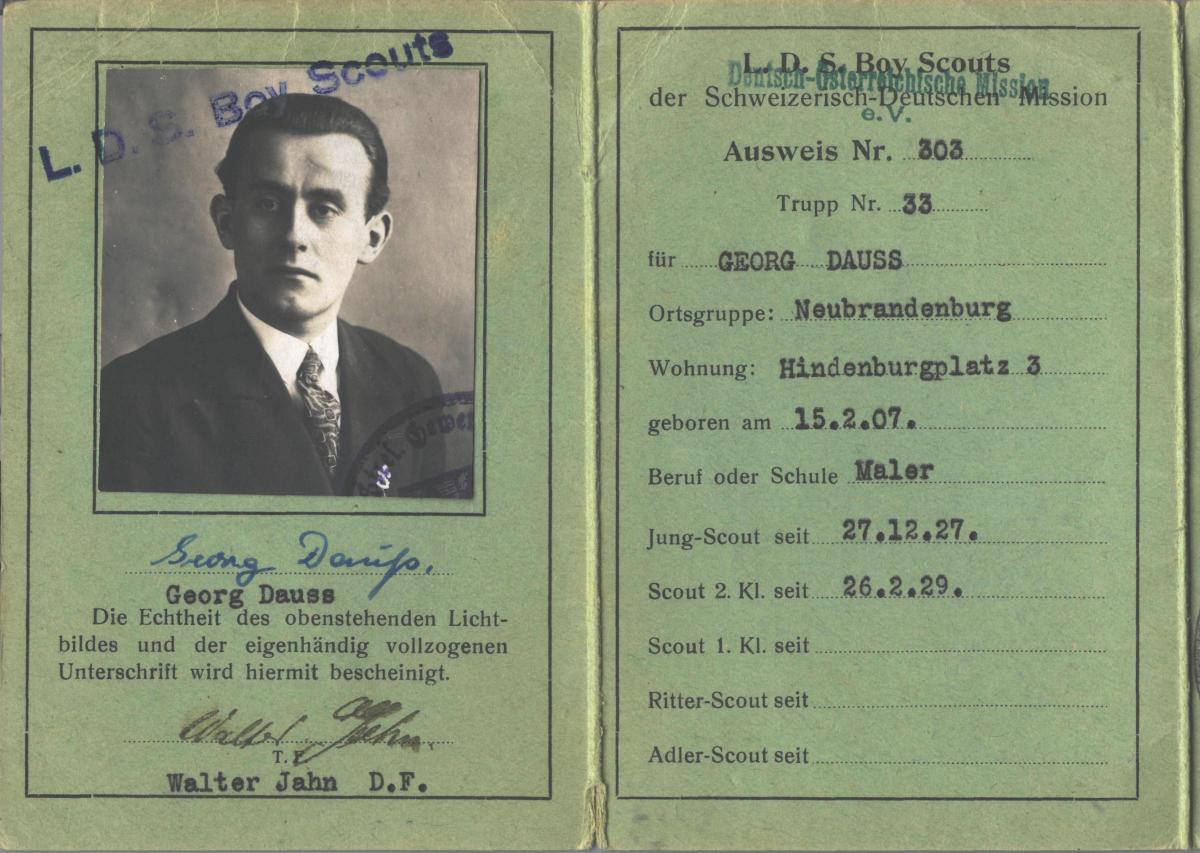

Georg Albert Johannes F. Dauss b. Burg Stargard, Mecklenburg-Strelitz 15 Feb 1907; son of Gustav Friedrich Emil T. Dauss and Anna Auguste Luise Utech; bp. 16 May 1928; lance corporal; d. France 4 Sep 1944; bur. Bourdon, France (CHL CR 375 8 #2459, 1405–1406; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Georg Dauss was killed in France in 1944. He is shown here as a registered Boy Scout. (W. Leonhardt)

Georg Dauss was killed in France in 1944. He is shown here as a registered Boy Scout. (W. Leonhardt)

Gerhard R. O. Ebert b. Neubrandenburg, Mecklenburg-Strelitz 6 Sep 1910; son of Ernst Emil Reinhold Ebert and Alwine Karoline Wilhelmine Lahde; m.; corporal; k. in battle Karlovy Vary, Czechoslovakia 6 May 1945; bur. Karlovy Vary (CHL CR 375 8 #2460, 514–515; FHL Microfilm 25759, 1925/

Gustav Adolf Ebert b. Hohenkirch, Briesen, Westpreussen, Preussen 19 Oct 1882; son of Johann Ebert and Auguste Pauline Templin; bp. 8 Feb 1913; conf. 8 Feb 1913; ord. elder; m. 19 Oct 1908, Emma Furth Aksmann; d. 18 May 1941 or 2 Feb 1942 (FHL Microfilm 25759, 1935 Census; CHL LR 6008 21, no. 5; Geschichte der Gemeinde Rostock)

Otto F. W. Ebert b. Neubrandenburg, Mecklenburg-Strelitz 20 May 1912; son of Ernst Emil Reinhold Ebert and Alwine Karoline Wilhelmine Lahde; m.; k. in battle Aug 1944 (CHL CR 375 8 #2460, 514–515; FHL Microfilm 25759, 1925/

Karl Ernst d. 1945 (CHL LR 6008 11)

Heline Luzinde Friederike Bernhardine Farnow b. Neubrandenburg, Mecklenburg-Strelitz 26 Aug 1875; dau. of Fritz Farnow and Auguste Boll; bp. 8 Oct 1919; conf. 8 Oct 1919; d. old age 20 Dec 1941 (CHL LR 6008 21, no. 11)

Gustav Adolf Klappert b. Ferndorf, Westfalen, Preussen 24 Aug 1902; son of August Heinrich Gustav Klappert and Auguste Dickel; bp. 27 Jul 1929; m. Neubrandenburg, Mecklenburg 18 May 1934, Emma Bauer; 6 or 7 children; d. POW Stalinsk, Russia 12 Apr 1946 (W. Rohloff, www.volksbund.de; IGI; AF)

Richard Klappert b. Ferndorf, Westfalen, Preussen 17 Sep 1912; son of August Heinrich Gustav Klappert and Auguste Dickel; k. in battle about 1943 (AF; IGI)

Willi Klappert b. Ferndorf, Westfalen, Preussen 25 Jul 1914; son of August Heinrich Gustav Klappert and Auguste Dickel; bp. 1 Sep 1929; conf. 1 Sep 1929; corporal; k. in battle Jegiorcive, Poland 2 Sep 1939; bur. Mlawka, Poland (CHL LR 6008 21, no. 80; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Paul Karl Wilhelm Meyer b. Köpenick, Berlin, Brandenburg 12 Dec 1889; son of Karl Wilhelm Meyer and Klara Agnes Krause; bp. 9 Jul 1932; m. Köpenick 5 Dec 1914, Else Albertine Rosalie Utech; 2 children; d. suicide 30 Apr 1945, Cammin, Mecklenburg-Schwerin (IGI; Meyer-Dierking)

Alexander Friedrich Rosenow d. 9 Mar 1943 (CHL LR 6008 11)

Liddi Gertraud Charlotte Schell b. Nordhausen, Sachsen, Preussen 17 Jun 1926; dau. of Karl Franz Schell and Frieda Paulmann; bp. 18 Sep 1937; conf. 18 Sep 1937; k. air raid 4 Apr 1945 (CHL CR 375 8, no. 5; IGI)

Ernst Otto Gottfried Schulz b. Nörnberg, Pommern, Preussen 7 May 1885; son of August Friedrich Hermann Schulz and Auguste Wilhelmine Karoline Bloedow; bp. 27 Jun 1922; conf. 27 Jun 1922; m. Riudorf, Brandenburg, Preussen 23 Nov 1910 or 1911, Ida Wilhelmine Sophie Schmidt; 3 children; d. Accident, Trollenhagen, Neubrandenburg, Mecklenburg 6 Oct 1939 (CHL LR 6008 21, no. 30; Schulze-Bamberger; IGI)

Hans Steudt b. Pasewalk, Brandenburg, Preussen 20 Nov 1913; son of Rudolf Karl Steudt and Anna Wilhelmine Elfriede Johanne Leesch; k. in battle 8 Mar 1945 (CHL CR 375 8 2458, 1474) (CHL 2458, Form 42 FP, Pt. 37, 1474–75; IGI)

Rudi K. A. Steudt b. Neubrandenburg, Mecklenburg 16 Mar 1927; son of Rudolf Karl Steudt and Anna Wilhelmine Elfriede Johanne Leesch; bp. 30 Aug 1930; conf. 30 Aug 1930; k. in battle 17 Apr 1942 (CHL LR 6008 21, no. 54; IGI)

Karl Ernst Eduard Toebe b. Lieteldam [?] 17 Feb 1893; ord. priest; ord. elder; m. Else Johanna Bertha Rosenow; 1 child; d. typhus before 1946 (FHL Microfilm 245286, 1925/

Else Albertine Rosalie Utech b. Grabow, Pommern, Preussen 14 Dec 1891; dau. of Wilhelm Karl Heinrich Utech and Christine Albertine Friedericke Kuehl; bp. 19 Aug 1922; conf. 19 Aug 1922; m. Köpenick, Berlin, Preussen 5 Dec 1914, Paul Karl Wilhelm Meyer; 2 children; d. suicide, 30 Apr 1945, Cammin, Mecklenburg-Schwerin (CHL LR 6008 21, no. 34; Meyer-Dierking; IGI; AF)

Joseph Weigand b. München, Oberbayern, Bayern 15 Feb 1875; son of Karl Weigand and Marie Reiser; bp. 14 Feb 1931; conf. 14 Feb 1931; m. 30 Jan 1906, Anna Lange; d. 3 Jun 1941 (CHL, LR 6008, no. 85)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 50, East German Mission History.

[3] Frida Bauer Kindt, interview by the author, Greendale, Wisconsin, August 19, 2007.

[4] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 46.

[5] Ibid., 1939, no. 59.

[6] Ibid., no. 52.

[7] Rostock Branch, history (unpublished), January 12, 194; private collection.

[8] German public schools were in session every Saturday until noon in those days.

[9] Anni Bauer Schulz, autobiography (unpublished), 45; private collection.

[10] Waltraud Meyer Dierking, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, April 12, 2008; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[11] Vera Schulz Bamberger, interview by the author, Neubrandenburg, Germany, June 9, 2007.

[12] Mein Kampf (My Struggle) was written by Adolf Hitler in 1925 and outlined his plans for Germany and Europe. Its length and boring presentation prevented most Germans from reading it. In many ways, however, it proved to be prophetic.

[13] Fred Streuling, interview by the author, Provo, Utah, March 26, 2006.

[14] Walter Rohloff, autobiography (unpublished), 48; private collection.

[15] Ibid., 51.

[16] Ibid., 52.

[17] Schulz, autobiography, 66.

[18] Rohloff, autobiography, 56.

[19] Ibid., 57.

[20] Ibid., 70.

[21] Ibid., 79–81.

[22] Ibid., 83–84.

[23] Ibid., 92.

[24] Ibid., 97–99.

[25] The promised weapons were the so-called Vergeltungswaffen (weapons of vengeance) such as the V2 missile and jet-engine aircraft. Both types existed at the time, but production never fulfilled Hitler’s expectations.

[26] Schulz, autobiography, 86–87.

[27] Ibid., 87–88.

[28] Listening to enemy radio broadcasts was illegal in Germany during the war. Several broadcasts in German could be picked up on radios all over Germany.

[29] During the final months of the war, concentration camp guards were ordered to transport camp inmates away from the advancing Allied armies. The train Günter saw apparently came from a camp in Poland and was headed west.

[30] Otto Krakow, “Twenty-five Years a Branch President in Neubrandenburg,” in Behind the Iron Curtain: Recollections of Latter-day Saints in East Germany, ed. Garold N. Davis and Norma S. Davis (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 101.

[31] Ibid., 104–7.

[32] Rohloff, autobiography, 110–11.

[33] Schulz, autobiography, 88.

[34] Rohloff, autobiography, 118.