Königsberg Branch, Königsberg District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 294-309.

The historic capital city of the Prussian province of East Prussia was Königsberg, a center of science and culture for hundreds of years. Although it was far from the heart of Germany, this city was part of the national consciousness. It had been cut off from Germany after World War I but was not forgotten by Hitler’s government in the 1930s. In 1939, the city had about 300,000 inhabitants.

| Königsberg Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 21 |

| Priests | 7 |

| Teachers | 17 |

| Deacons | 19 |

| Other Adult Males | 86 |

| Adult Females | 266 |

| Male Children | 19 |

| Female Children | 30 |

| Total | 465 |

Eyewitnesses report a large population of Latter-day Saints in the 1920s, but a wave of emigration had seen at least one hundred of them leave for the United States. There were as many as three branches of the Church in Königsberg shortly after World War I (1918). With 465 members, the Königsberg Branch was the second-largest in all of Germany on January 1, 1939.

The Königsberg Branch met in rented rooms at Freystrasse 12 on the main floor of the first Hinterhaus. Three daughters of district president Max Freimann—Irmgard, Ingrid, and Ruth—later stated that Church meetings were held at that same location throughout the war.[2] They described the rooms as follows:

The rooms were in the Hinterhaus. When we went inside there was a small room that also led to the wardrobe and the restroom. The next room was the large room with a curtain and a podium for theater plays and other special occasions. Walking up some stairs, there was another large room and two or three classrooms. The choir did not stand on the rostrum but on the floor to the side. The room upstairs was large also, and we used it for some meetings when the room downstairs was too small.

Their younger brother, Reinhard Freimann (born 1933), added these details to the description of the facilities:

There was also a sign that said that we were the Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der Letzten Tage and people who walked past [the main building] could see that there was a church in the back building. We also had an organ in the largest room.[3]

The Freimann sisters recalled the following about the meetings:

Sunday School started at 10 a.m. and after that we went home [and came back later for sacrament meeting]. We lived in the Schleiermacherstrasse 51. It was pretty far away. We could have taken the street car, but that would have cost too much money for the entire family, so we walked about forty-five minutes (one way) to church on Sunday. We had an attendance of two hundred people and more than one Sunday School class—up to four different ones.

As in other branches, auxiliary meetings were held on several evenings in the week and Primary on Wednesday afternoons.

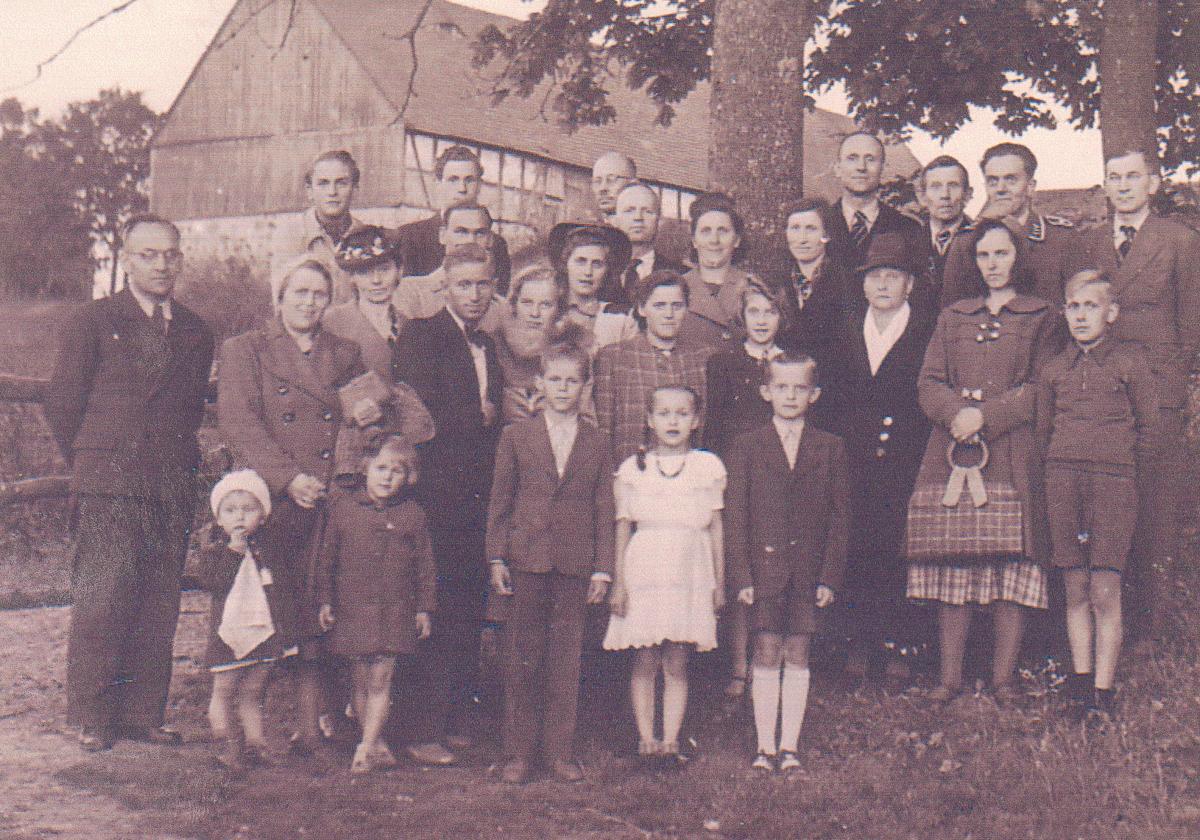

The family of district president Max Freimann in about 1937 (Freimann sisters)

The family of district president Max Freimann in about 1937 (Freimann sisters)

In July 1939, Elder Joseph Fielding Smith visited Königsberg and presided over a district conference. Renate Klein (born 1930) was baptized in connection with the conference. “I was the newest member of the Church attending the conference, so I got to shake [Elder Smith’s] hand.” The Emil and Auguste Klein family had just moved from Königsberg to Bartenstein, about thirty-five miles to the south. Emil Klein was not a member, but supported his family in their Church activity. For example, he allowed his wife to pay tithing on his income because she had no income of her own. She and her daughters made it to Königsberg only to attend district conferences and a few other special occasions.[4]

“We had a good Relief Society and we had lots of training classes there. I never had any interest to go elsewhere to learn how to cook or to sew.” Such was the recollection of Inge Grünberg (born 1927). She also had the following memories of Sunday School:

When the opening exercises for Sunday School were over, we all stood up and the children on the front row marched out (there was a tiny bit of a military spirit about it) to their classrooms. We had about 120–150 in church on a typical Sunday.[5]

Membership in the Bund Deutscher Mädel (League of German Maidens) was a challenge for Inge Grünberg. However, as she later explained, there were ways to be both a good Latter-day Saint and a loyal member of the Hitler Youth group on Sundays:

At 10 a.m., when we were starting our [Church] meetings, the BDM gathered and went to the movies. I went with them until we were seated in the theater and the lights went down. Then I sneaked out, changed my clothes, and put my BDM stuff in my bag and went to church. My friends didn’t report me.

With his classmates, Reinhard Freimann was inducted into the Hitler Youth program when he turned ten. As he later explained,

I was a member of the Jungvolk. I went every week to all the meetings that we had, but I can remember, I only went twice on a Sunday. The normal meetings were held on Sundays and that was a conflict but nobody complained about [my absence]. My parents did not state their opinions about the regime or politics in general. They remembered our [twelfth] article of faith, which states that we should accept our leaders and not work against them.[6]

Regarding the life of Latter-day Saints in Königsberg during the war, Inge Grünberg (born 1927) had these recollections:

Our [Church] meetings continued as always. We were cut off from the Church in America and eventually we didn’t get the Stern [Church magazine] any more. People lost their hymnbooks and scriptures when they were bombed out. We kept all of the Church traditions (celebrations, etc.) through the war the best we could.

Erika Jenschewski (1925) served her Pflichtjahr on a farm from 1939 to 1940. She was miserable on the farm, especially in the winter when she was required to run across frozen fields to procure food ration coupons. As she explained, “In those days women were not allowed to wear pants and dress warm. I was just screaming for cold, and when I came back, my feet were frozen. I had really bad frostbite all over.” Erika wanted to be a saleslady but was not allowed to train for that work for several more years. She first had to learn domestic skills.[7]

The Königsberg Branch in 1938 (Freimann)

The Königsberg Branch in 1938 (Freimann)

Inge Freimann finished school in 1940 and planned to study clothing design, but was told, “Your plans can’t be fulfilled. You must have forgotten that there’s a war on.” She was assigned to work in an office at the army post and learned office skills. “One day I found a letter on my typewriter; I was being sent to Böhmisch Chamnitz [Czechoslovakia] for a course in office skills for three months with twenty young women. I cried my eyes out because I had to leave.”

Karl Margo Klindt of the Flensburg Branch was a sailor stationed in Königsberg, where he met Irmgard Freimann. For several years, they planned to be married, but his service in the navy resulted in delays. Finally, he received permission to marry after the German victory over Poland, and the wedding took place in Königsberg on December 30, 1939. Within a week, he returned to his unit.

Ruth Freimann (born 1921) fell in love with a man who had been a Catholic priest—Franz Holdau of Wuppertal in the Rhineland. He had arrived in Königsberg in 1942 and was already acquainted with the Book of Mormon. He attended branch meetings and became interested in Ruth. As she later stated, “He asked me if I would marry a man of another church, and I said, ‘Never!’” He was baptized in November 1942. Soon they were engaged, and Ruth recalled the events connected with the wedding:

We got married in the civil registry office [at city hall] first and then went over to the Church. We celebrated our wedding all night long. We danced and had nice food. Every member of the branch attended, and I wore a white dress.

Like so many wartime weddings, this one left little time for a honeymoon. They visited Franz’s parents in Wupperthal. By June 30, Ruth was back at home in Königsberg, and Franz was on his way to his Wehrmacht unit in Russia. Life as a new bride did not last long for Ruth Freimann Holdau. On August 3, less than two months later, Franz was killed near Ladoga Lake in Russia, leaving Ruth a widow.

Sigrid Klein (born 1932) was baptized in a secret ceremony in the Pregel River in Königsberg in the summer of 1941. It was a memorable event in her recollection: “It was at 5:00 a.m. I was wearing a white nightgown and got covered with oil. It was near the harbor and a tanker had leaked oil. I looked terrible! I don’t know how they ever got me clean!”

The education of Germany’s youth suffered in large cities during the war. Christel Freimann (born 1931) recalled interruptions in Königsberg: “We often missed school. When there was an alarm [while we were] in school, we went into the shelter. But when the school was destroyed, they told us to stay home until they found some other building that we could have class in.”[8]

The sorrows associated with a father leaving his family to report for military duty represent an international phenomenon, and many Latter-day Saint families experienced this. Karin Kremulat (born 1938), recalled when her father left home:

He did not volunteer, no, he wanted to stay with his wife and with his two little girls and he did not want to go at all. My mother would even say, “Do you have to go? Why don’t you just stay with us? We can hide you.” And he would say, “You have no idea what they would do to me. I have to go,” and so he did.[9]

The last time Karin saw her father was at Christmas in 1943. Soon after that, he was reported missing in action. His wife, Louise Schipporeit Kremulat, mourned her husband for several years. According to Karin, “[Christmas was] a very sad time for my mother because after that she would never want to have a Christmas tree. I remember in later years my sister and I would go and find our own because it was such a hard time for my mother.”

Branch president Haase was a man of good humor, according to Erika Jenschewski:

He was very concerned about the young people. He really taught us to live a clean life, and he made lots of parties for us so that we were together. He was a very fine member. He had parties in his home where the young people came. . . . He was almost blind, but he was funny, a good leader.

Just after the war started, Inge (another Freimann daughter) met Alfred Bork, a youth from the Stettin Branch who was stationed near Königsberg. He became a frequent visitor in the Freimann home and eventually received permission from Max Freimann to be engaged to Inge. However, like so many other soldiers, Alfred returned to the front, and his visits to his fiancée in Königsberg were rare.

Friedrich (Fritz) Haase had served as the president of the branch for several years when he was drafted and sent to Russia in 1943. His counselors, Fritz Bollbach and Emil Jenschewski, directed the meetings in his absence. Brother Bollbach was a student at the State Building School and worked in the construction of barracks for POWs in Königsberg. His work in a high-priority war industry made him exempt from military service for much of the war. On July 1, 1944, he was awarded a master’s degree at the Institute for Vocational Advancement.

Members of the Königsberg Branch on an outing during the war (Freimann)

Members of the Königsberg Branch on an outing during the war (Freimann)

Bit by bit, the war was beginning to wear out the people of Königsberg. Irmgard Freimann Klindt recalled those days:

Our lives became one of survival. We had ration cards to get food. We were allowed a little butter, some bread, and a few eggs. Life was very routine. We continued attending all the meetings at Church and tried not to think about the war.[10]

In 1943, air raids and false alarms became an increasingly frequent aspect of life in Königsberg. Gudrun Hellwig (born 1934) recalled how she reacted to the sirens:

We had constant alarms and attacks. We went down to the basement during the night, and I had already developed a rhythm and got up every night at the same time, around 10:00 p.m., and left for the basement. We did not go to bed fully dressed, but everything was ready in case we needed to go.[11]

The war came home to Königsberg in all its brutality in 1944. The family of Theodor and Maria Berger were some of the city’s first Latter-day Saints to lose their home. During the night of August 27–28, an air raid struck their neighborhood. Sister Berger and her daughter, Renate—the only ones at home—sought shelter in their basement. Maria later described the event in these words:

Because fire raged all around us, a heavy iron door, our only way out, expanded and would not budge. We were trapped. Fear set in. The shelter was filled to capacity, and the air supply was limited. It is hard to describe the destruction we found when we finally were able to leave the shelter in the morning. The Cranzer Allee was a long, wide street. Every single house had collapsed and was enveloped in a blazing fire. The sea of flames created a big [wind] storm. Everyone tried to find their home site. We stood in total shock by the smoldering ruins of our house. In the rubble we found a small, engraved plate from our piano, the only sign that we once lived there. . . . We cleaned up and . . . went to church.[12]

The Bergers had lost everything, including the genealogy papers tracing Brother Berger’s ancestry to the 1500s. Fortunately, the Bergers were taken into the home of Sister Marie Jenschewski that very day.

Little children were taught how to behave during air raids. Helga Kremulat (born 1937) had vivid memories of the procedures:

We had these black shades that we had to put in front of the window. . . . We had to make sure that there was not any light coming through, so they wouldn’t see where there were homes, when the airplanes would come over. . . . And we had to go down in the basement—because we lived farther upstairs—we had to have a little suitcase ready to take downstairs with our important papers. My mother had to take care of this.[13]

Inge Grünberg recalled similar experiences:

When the air raids came, all six of the families in the apartment house were to gather in the basement as a shelter. Once, we decided that we wouldn’t go down there. Then we discovered that all of the other people were sitting in front of our door and on the stairs. They said, “If you don’t go to the basement, we won’t either, because you pray. We want to be where you are.” They hadn’t learned how to pray.

Inge worked as an office staff member at an army post for the last few years of the war. On at least one occasion, she escaped disaster:

Once my friend begged me to do her weekend shift, so that she could be with her new husband. I did her shift and she did mine the next week so that I could celebrate my birthday. The next day I went to the office and found that it had been destroyed. My friend lay there, burned to death and a very small corpse. I was saved again by my Heavenly Father.

In late 1944, Emma Klein took her daughters, Renate and Sigrid, to Königsberg for another district conference. The city had just suffered a devastating air raid, and the Kleins viewed the ruins of the downtown as they rode the streetcar to church. When they told the driver they wanted to get off, he told them that there was nothing left in the neighborhood. Nevertheless, they got off and walked around the corner. According to Renate, “We saw that the [church building] was standing, but the house in front and the houses on either side were gone. And our building had those huge windows—not one window pane was broken.”

The Freimann sisters recalled that during the attacks on Königsberg, people wanted to be in the same shelter as Max Freimann: “Many came into our basement because they knew that we would be protected. Our father prayed on those nights. Our father never forgot to tell anybody else that we were members of the Church.”

Irmgard Freimann Klindt’s husband, Karl Margo Klindt, was taken prisoner by the British shortly after the Allied invasion of Normandy in June 1944. As Irmgard explained, “I thought he was dead. . . . The German government thought he had deserted. . . . They wanted to put my father-in-law in prison for [hiding] him.” With the help of a Danish uncle, it was finally learned that Karl was a POW in England.[14]

The meeting rooms at Freystrasse were confiscated by the National Socialist Party in December 1944. The branch was temporarily allowed to hold meetings in a nearby Protestant church. However, that lasted only two weeks because the Protestant church council retracted their invitation. Meetings were next held in the home of Emil and Marie Jenschewski.[15]

Leaders of the East German Mission understood that many of the Saints in the districts of eastern Germany would have to leave their homes if Germany were invaded by the Red Army. As Inge Grünberg recalled, “[Mission second counselor] Paul Langheinrich told us all in East Prussia to send a box with our important documents to a specific family in western Germany.”[16]

In March, Inge Grünberg was allowed to leave the city. Her mother had already gone to Dresden and was there during the firebombing of February 13–14. Inge did not arrive until after that terrible event, as she explained:

In March 1945, I made my way to Dresden to be with my mother. The bridges were destroyed, and I found a fisherman who took me across the Elbe and [I] paid him with cigarettes. I was there for only one day because I had to move on to Magdeburg to work at the army post. The officers were burning lots of papers there. I was to report there on March 21 and was worried that I would be called a deserter if I didn’t show up.

Gudrun Hellwig did not recall a formal evacuation order for women and children in Königsberg, “But my father had already noticed that the wounded were taken out of the military hospitals, and then he decided that we had to leave also.” He found the family a place on the train heading west to Pillau, a small port on the Baltic Sea. Gudrun recalled that military police removed men from the train at various stops, ordering them to stay and defend what had been declared “Fortress Königsberg.” Gudrun’s father, a streetcar driver, also remained in the city as a member of the Volkssturm.

During the last year of the war, a heroic and desperate effort was initiated to evacuate German civilians from the eastern provinces by boat across the Baltic Sea to northwestern Germany. This campaign involved hundreds of military and commercial ships as well as private vessels. By the end of the war, several million people had been transported across the Baltic. Gudrun’s mother, Margarete Hack Hellwig, recognized this route as the simplest and fastest, and she and her daughter joined thousands of others hoping to secure a place on a ship. Gudrun remembered the terrible cold at the port:

We then reached Pillau, and it was very cold—sometimes down to –20 degrees Celsius. We slept in a large room that night, and it was cold. The next morning I can remember standing at a pier and there was a large group of people. . . . My mother had to concentrate so that she wouldn’t lose me in that group. There were large ships and people were trying to board and there was luggage lying all over the ground.

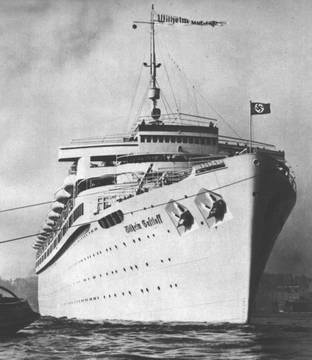

Margarete Hellwig and her daughter were taken on a small craft from Pillau to Gothenhafen, where they joined a huge group of refugees on board the Wilhelm Gustloff. It was a transport vessel that still bore the markings of a hospital ship. Squeezing their way past other harried refugees, Hedwig and her mother found a spot in a hallway down below, next to the engine room where it was nice and warm. Then there came an announcement over the intercom that the ship was dangerously overloaded and that some of the passengers would have to disembark. Volunteers were sought urgently. Gudrun clearly recalled what happened next:

My mother was always praying and at that moment she didn’t have a good feeling; she told me that we would have to leave the Wilhelm Gustloff. I protested a bit because I was so tired and our spot was so warm. But she insisted, so we got off the boat.

Margarete Hellwig later described her feelings aboard the doomed vessel:

All of a sudden, I became really scared. It seemed as if somebody wanted to push me out. I told my daughter, Gudrun, “I’m not staying in here, I’ve got to get out!” She answered, “Mommy, it’s so warm, let’s stay here!” “No, I’m not staying here, I have to get out!” I was so very frightened. So we moved to another ship.[17]

The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff on January 30, 1945, took the lives of thousands of refugees.

The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff on January 30, 1945, took the lives of thousands of refugees.

Sister Hellwig’s decision saved their lives. They boarded a smaller vessel that left the harbor with the Wilhelm Gustloff. It was the night of January 30, 1945. Just after 9:00 p.m., the Wilhelm Gustloff, loaded with an estimated ten thousand passengers and crew, was attacked by a Soviet submarine. Struck by three torpedoes, the ship went down in about ninety minutes, spilling many of its passengers into the frigid waters of the Baltic. Only about 1,200 passengers were rescued.[18] The sinking of the Wilhelm Gustloff was the worst maritime tragedy in recorded history. Having been unable to sleep, Sister Hellwig watched the catastrophe from the deck of the trailing ship. She was convinced that their escape from death was due to the intervention of the Holy Ghost.

Maria Berger and her daughter, Renate, fled Königsberg on January 26, 1945, after receiving warnings from friends and neighbors. Learning that an important bridge along the land route to Berlin had been destroyed, they joined with three other women and headed for the Baltic Sea. They were unsuccessful in boarding the transport ship Wilhelm Gustloff, but found places aboard the smaller vessel Maria Vissa. When the ship made a stop in the Danzig harbor, the passengers learned that the Wilhelm Gustloff had been sunk. As Maria Berger later wrote, “We had tried so desperately to get on that ship. How grateful we were now, not to be among those who perished in the ice-cold waters of the Baltic Sea.”[19]

The Bergers left the boat at Wollin and made their way by train to Berlin, where the Paul Langheinrich family took them into what was a growing Latter-day Saint refuge in the apartment house at Rathenowerstrasse 52. They spent the remainder of the war in that building and were given Church assignments that they gladly fulfilled.[20]

Desperation led Marie Jenschewski to employ a daring ruse to save her son, Helmut. At sixteen, he was not allowed to leave Königsberg, where boys of Hitler Youth age were required to defend the city against the invading Soviets. Fearing that he would not survive the conflict, Sister Jenschewski and her daughter, Erika, dressed the boy up as a girl. According to Erika, “We put a dress on him and he had a scarf around his neck and he looked very cute. So he got away with us. We left Königsberg on January 26, 1945. We had one suitcase for all of us and we had to ride in a cattle car.” Of course, their father, Emil Jenschewski, was not allowed to leave Königsberg.

The Jenschewskis rode the train to Pillau, where they boarded a ship for Danzig. From there another train took them to Berlin. On the way, Marie Jenschewski was carrying tithing funds she was determined to deliver to the mission leaders. To ensure the money’s safety, she had hidden it under her clothing. At the mission home on Rathenowerstrasse, she turned over the entire sum to the mission leaders. She was then instructed to take her children to Zwickau, where Church members would provide them a place to live. The Jenschewskis arrived there in February 1945 and were indeed treated very well by the members of the Zwickau Branch.

The Jenschewski family of the Königsberg Branch. The children in the back row (Edith, Kuno, and Erika) were members of Hitler Youth organizations. (E. Jenschewski Koch)

The Jenschewski family of the Königsberg Branch. The children in the back row (Edith, Kuno, and Erika) were members of Hitler Youth organizations. (E. Jenschewski Koch)

In early 1945, Louise Kremulat took her daughters Helga and Karin and left Königsberg with little time to spare. They had packed a wagon (a typical Bollerwagen measuring about four feet long, two feet wide, and two feet deep) and made their way to the railroad station. As Karin recalled,

We were on the last train that left Königsberg, and it was supposed to take us to Austria. It never did. It went through Czechoslovakia and about [sixty miles] past Prague. The train stopped and was bombed. For some reason it was not going to Austria and everyone left the train—we were on our own. So we picked up our bundles and started walking.

Fortunately, their Bollerwagen somehow survived the railroad journey, and they loaded it for the trip north back toward Prague. Karin’s story continued:

We packed that Bollerwagen full and we pulled it. My aunt had one too, and we helped her pull it. I pulled the wagon about two hours and my mother and my sister helped with the other wagon and my aunt pushed the baby buggy, so it was really a pitiful sight.

Karin Kremulat turned seven years old the day the family entered Prague. It was May 8, 1945, the day Germany formally capitulated. At that point, however, their party of refugees was totally isolated—no German troops to defend them, no transportation to move them, nobody to feed them, but plenty of Czech freedom fighters and Soviet invaders to harass them. As Karin’s older sister, Helga, recalled:

It was very scary because sometimes the Russians would come on their horses and say, “If you’re hiding any soldiers here, we’re going to shoot you all.” Of course, for me, it was very scary. My sister was a year younger, and she just kind of looked them in the eyes and thought, “Gee, this is exciting to see these Russians on their horses.” My mother claimed that because my sister looked them in the eye, they left and let us alone.

From Prague, the women and girls made their way north into Germany, then west and north to the town of Milbergen near Minden, where the girls’ grandmother was living. The war was over for Louise Kremulat and her daughters, but the search for her missing husband lasted for several years. Sister Kremulat sought information from government agencies and the Red Cross and carefully studied the lists of prisoners released from Soviet camps, but her husband was never heard of again.

Max Freimann was inducted into the Volkssturm and was gone much of the month of January 1945. His son, Reinhard, recalled that Brother Freimann was not freed from Volkssturm duty even long enough to accompany his family to the railroad station. He had to say good-bye at the streetcar stop then return to his post. As Irmgard Freimann Klindt wondered years later, “How could we have known that we would never see our father or our home again?”[21]

As the Freimann family made their way west, Ruth and Irmgard managed to find their way to the Island of Rügen to visit Inge. From there, they backtracked to Demmin to meet their stepmother, Helena Freimann. The women then took a train to distant Flensburg, where they arrived in early February. They spent the rest of the war in peace and safety there.

Emma Klein left Königsberg with her two daughters and headed west. They traveled past Dresden, then south into Czechoslovakia. Emil Klein was required to stay in East Prussia but was able to get away before the war ended (due to a leg damaged in World War I, he was exempt from military service). He caught up with his family near Karlsbad, Czechoslovakia, at the end of February 1945. Sigrid Klein later recalled the reunion: “He arrived at midnight and we were thrilled. We wanted to hug him, but he said, ‘Don’t touch me! I have lice.’ It didn’t matter; we were happy to have him back again.”

Just a few weeks after the end of the war, the Klein family began the trek northward back into Germany. They had been expelled from Czechoslovakia on short notice and began walking toward Chemnitz, pulling a two-wheeled cart with what belongings they could rescue. Along the way, Emil Klein told his daughter, Sigrid, something surprising: “You know, when we get back to a town where there’s [an LDS] church, I’m going to be baptized.” (He kept his promise and was baptized in August 1945.)

Arriving in Chemnitz, Emma Klein knew that a branch of the Church was nearby but had no idea how to find it. At the railroad station at 6:00 a.m., she spoke to a man who was sweeping the floor. He thought that she was looking for the Jehovah’s Witnesses until she mentioned the name “Mormons.” Then he said, “I’m not a Mormon, but I know one,” and proceeded to give her the address of the family about two miles across town. Sister Klein went there alone and heard the same response again: “I’m not a Mormon, but I know one.” This man gave her the address of the family of Richard Burkhardt, just a block away. The Kleins, who had been traveling with the Paulus family of five, were quite relieved to be taken into the Burkhardt home, and space was found for the Paulus family as well—nine persons in all. The Kleins were grateful that their own lives were spared, but they later learned that a total of twenty-six close relatives had died in the war (none of whom were Latter-day Saints).

Toward the end of January 1945, Fritz Bollbach and several other men from the branch decided to leave Königsberg and make their way to the west. Knowing that they could easily be accused of desertion and executed for abandoning Fortress Königsberg, they cautiously walked toward Pillau on the Baltic Sea. They narrowly avoided arrest on one occasion but were eventually caught and inducted into the Volkssturm. With about one hundred other civilians, they heard these words from an officer of the SS: “Men, you are not prisoners; you are being inducted into the militia to defend our fatherland. Do not attempt to flee. The sentries are instructed to shoot if you do.” The serious nature of the warning became shockingly real shortly thereafter when Fritz came upon a scene that filled him with deep sadness—the bodies of men accused of treason and desertion:

The closer we got, the more horrible the view. On either side [of the road], men, soldiers, and civilians hung on large beeches [trees]. Most had a sign fastened on the chest with handwritten labels: deserter, absent without leave, cowardice in the face of the enemy, etc.[22]

Fritz was horrified that Germans would kill Germans while the Third Reich came crashing down around them. During March and April, Fritz was assigned first to drive a motorcycle and deliver messages, then to drive a truck to deliver food and other supplies. As the Red Army advanced slowly toward the Baltic Sea coast and the masses of refugees grew larger and more desperate, Fritz saw ever-increasing degrees of violence. Desperation drove people to rash acts, as he witnessed on one occasion when a Soviet artillery shell injured two horses hitched to a wagon:

Before we could do anything, some people were already cutting pieces of meat from the legs of the still living animals. It was [a] terrible sight. I believe that people were already eating the flesh while the horses were still alive.[23]

In late April 1945, Brother Bollbach managed to escape from his forced militia assignment by disguising himself as a railroad worker and sneaking aboard a tugboat that transported him to the Hela Peninsula. There he managed to jump aboard a ship that had cast off and was already three feet from the pier. He had risked execution for desertion but was finally on his way across the Baltic. The ship took him to Copenhagen, Denmark, where he was imprisoned by British soldiers. Fritz’s short but harrowing military experience was over.[24]

Gudrun Hellwig recalled spending nearly a week on the Baltic Sea under foggy conditions. “Our ship was listing to one side so maybe it had been damaged too.” They landed at the harbor of Kiel, Germany, and made their way inland. Being some of the first refugees to arrive in the rural province of Schleswig-Holstein, they had no problem finding a place to stay on a farm near Krummberg. There they waited out the end of the war, hoping to be united with their relatives.

The search for loved ones began even before the war ended, and Gudrun Hellwig remembered the scenes: “The husbands and wives looked for each other and wanted to find their families. They put up pictures and [wrote in chalk] names on walls so that people could see who was looking for whom.” Eventually, they found Margarete Hellwig’s sister and Gudrun’s father; he had been released from a Soviet POW camp.

Some of the most detailed Latter-day Saint documents to survive World War II are the letters of Theodor Berger (born 1893), an elder in the Königsberg Branch. Like all men ages sixteen to sixty, Brother Berger was required to stay in “Fortress Königsberg” to defend the city against the invading Red Army, while the women and children were permitted to leave. On January 26, 1945, Brother Berger sent his family to Berlin to the home of Paul Langheinrich, second counselor to the supervisor of the East German Mission. He mailed several letters to his wife at the Langheinrich home from February 7 to April 2. The following excerpts from his letters provide insight into the condition of the men who were forced to stay and defend the city:[25]

February 7, 1945

Dear mother, where are you and Renate? I am still alive and well, am considered “military” and have to work at the “Zeugamt” [weapons arsenal].

February 14, 1945

We were under terrible artillery fire. Dead and injured covered the streets. I stayed calm and prayed to God to hold His protecting hand over me and especially to protect you. Should I die, I know it is His will. I have accepted the end. Königsberg is now surrounded but not hopelessly delivered to the Russians.

February 22, 1945

I would be so very happy just to know you are safe in Berlin or some other place.

February 25, 1945

The Russians have committed many atrocities. It can’t go on much longer. The German army fights so hard to keep the city. Artillery fire keeps me awake, I can’t sleep anymore. I am so grateful that you don’t have to live through this.

March 1, 1945

I was paid on February 15. Money is now worthless, but I still want to pay tithing and will give it to Brother Freimann on Sunday night when all members will meet again. (There are fifteen of us left.) We do not know anymore which day of the week it is. Nothing matters!

March 5, 1945

The uncertainty is hard to endure. I hope it will not be a terrible end full of horror.

March 21, 1945

We hear that Berlin gets bombed daily. My heart aches for you. I wish I knew more about your fate.What does the future hold for us? Even if we are reunited, our lives have been changed forever.

March 24, 1945

Good news, your letter arrived! I was so happy to hear from you. I am glad that you have a place to stay, that you are with friends and feel the Lord’s blessings. We here will get together on Sunday and be with you in spirit and thank God that we are still alive. Please don’t despair even when it gets hard to hold your head up high. Our faith in God will make us strong.

March 25, 1945

On Sunday, seven faithful members gathered together to worship. Present were: Brothers Freimann, Jahrling, Jenschewski, Seliger, and Berger, and Sisters Habermann and Hesske. It was comforting to talk about how we suffer, with families scattered everywhere not knowing from day to day if they are still alive and yet always hoping to be reunited again. I do believe that our Father in Heaven is with me and will shield me from pain and suffering. I pray daily for His mercy and hope that I can live to better serve Him. I am grateful to know that He does not withhold His blessing from any of His children who believe in Him. I feel a peace and quiet within even with bombs exploding around me. Should He call me, so be it. It will be His will.

April 2, 1945

Russian troops are closing in fast! Some members of the Church got together yesterday at Freimann’s apartment. When I got there, I found a room full of friends: Brothers Freimann, Seliger, Jahrling and Wetzker, and Sisters Hesske, Habermann, Freimann, Kolbe, Fett, Schmidt, Seliger, and Martsch. It was a good time. We gained strength from each other and shed many tears. So you see, we are not alone. God is with His children even in this surrounded fortress. A turning point is near. We know something will happen soon. May the Lord bless you in Berlin. All is in His hands. To know God is with me keeps my soul quiet, and I get comfort from one special song I remember: “Ruh, Ruhe dem Pilger” [Peace to the Pilgrim].

Auf Wiedersehen!

It was something akin to a miracle that the last message from Theodor Berger in Königsberg to his family in Berlin could actually be delivered after April 2, 1945. His letters represent priceless historical documents that attest to the devotion of the last surviving Latter-day Saints in Königsberg.

On April 9, the determined but hapless German defenders of Fortress Königsberg surrendered to the Soviets. The conquerors slaughtered many of the defenders—soldiers and civilians alike—and transported many others east to labor camps. Evidence suggests that not one of the Latter-day Saints mentioned in the Berger letters survived the fall of Königsberg. Berger family records show the date April 30, 1945, for Theodor Berger’s death in Königsberg. In 1952, a German court ruling declared Max Freimann dead.

Although Königsberg was surrounded by the enemy, this letter written by Theodor Berger on April 2, 1945, was somehow delivered to his wife, Maria, in Berlin a few days later (R. Berger Rudolph)

Although Königsberg was surrounded by the enemy, this letter written by Theodor Berger on April 2, 1945, was somehow delivered to his wife, Maria, in Berlin a few days later (R. Berger Rudolph)

Shortly after the war ended, Marie Berger was assigned an apartment in Berlin for her daughters and her grandson. She began a new phase of life without her husband.

Inge Freimann explained that her fiancé, Alfred Bork, had planned to serve a mission before being drafted by the Wehrmacht. Now and then he wrote to her about prophetic dreams he had:

He could always tell what would happen, and he would write me a letter before something terrible happened. I got a letter that he had sent on April 1 [from Königsberg], and he told me that he had dreamed of my mother (who had already passed away) and that they had been in a large field. She told him in that dream that they would see each other on Easter. The last letter that I received from him was sent on Easter. After that, I never heard from him again.

Alfred Bork disappeared in May 1945. Under the chaotic conditions in eastern Germany at the time, it can come as no surprise that the German army never reported him missing in action and the Soviets did not list him as a POW. Several years passed before Inge Freimann lost hope of seeing him again.

The war had been over for several months before Inge Grünberg’s wanderings finally ended. From Magdeburg, she had moved west into the Lüneburg Heath in the British Occupation Zone and from there to Flensburg near the Danish border. There she met Helena Freimann and learned the fate of several of the Saints in Königsberg.

Fritz Bollbach eventually located his wife and daughters through Red Cross search services. They were living in the new Latter-day Saint refugee community at Langen, south of Frankfurt am Main in western Germany. In August 1946, Fritz was released by his British captors, made his way to the American occupation zone, and was set free. He arrived in Langen on a Sunday and found the apartment where the family lived. Two daughters were at home, while his wife and the youngest daughter were attending church.[26]

Karl Margo Klindt was released from a British POW camp in February 1946. When he returned to his wife in his hometown of Flensburg, he was very thin and emotionally sick.[27]

Emil Jenschewski was released from a POW camp in Russia in 1948 and made his way back to Germany. His daughter Erika later recalled how the reunion took place:

He found out from the Berlin mission home where we lived. [At our apartment] he stood in front of me and I didn’t recognize him. He said, “Didn’t you know your father was so skinny?” His eyes were just sparkling. I looked at him and said, “You are my father.” So he was [finally] with us.

Unfortunately, one family member could not be located: Son Kuno Jenschewski had disappeared during the defense of Berlin just days before the war ended. He is still listed as missing in action.

With the conquest of eastern Germany at the end of World War II, the northern half of the province of East Prussia was ceded to the Soviet Union and with it the city of Königsberg (now called Kalinengrad). It is believed that all of the surviving members of the Königsberg Branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had left the city or were expelled by the new Russian government by the end of 1946. Once a stronghold of the LDS faith, the city was devoid of the restored gospel for at least the next four decades.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Königsberg Branch did not survive World War II:

Theodor Reinhold Berger b. Trebnitz, Schliesien, Preussen 10 July 1893; son of Otto Berger and Karolina Messner; bp. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen Germany 23 Aug 1924; conf. Königsberg 23 Aug 1924; ord. deacon Königsberg 28 Oct 1925; ord. teacher Königsberg 4 Aug 1930; ord. priest Königsberg 2 Apr 1933; ord. elder Königsberg 7 Mar 1937; m. Königsberg 23 Jun 1917, Maria Berta Bresilge; 2 or 4 children; MIA Königsberg 30 Apr 1945 (R. Berger Rudolph; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Karl Herrmann Bollbach b. Groß Bajohren, Preussisch Eylau, Ostpreussen, Preussen 10 Mar 1872; son of Friedrich Ferdinand Bollach and Henrietta Wilhelmine Dunkel; bp. 25 Sep 1920; m. Uderwangen, Preussisch Eylau, Ostpreussen, Preussen 28 Nov 1897, Wilhelmine Dunkel; 3 or 5 children; d. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen Mar or Apr 1943 OR 7 May 1943 (Fritz Bollbach; FHL Microfilm 25726, 1930 Census; IGI)

Heinz Werner Freimann b. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 2 Feb 1916; son of Max Gustav Freimann and Margarete Hedwig Krause; bp. 25 Jun 1924 Oberteich, Ostpreussen, Preussen; m. Königsberg 20 Jul 1940, Delila Zellmer; 2 children; sergeant major; d. H. V. Pl. D. 14 I. D., Braunsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 20 Feb 1945; bur. Braniewo, Poland (R. Freimann Dietz; www.volksbund.de; IGI; AF)

Max Gustav Freimann b. Taleiken-Jacob, Memel, Ostpreussen, Preussen 15 or 16 Dec 1888; son of Gustav Louis Freimann and Auguste Johanne Stolz; m. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 9 Oct 1915, Margarete Hedwig Krause; 6 children; 2m. Königsberg 26 Mar 1932, Wanda Helene Maria Sommer; 1 child; ord. elder 3 Nov 1929; MIA Königsberg Apr 1945; officially declared dead 9 Sep 1952 (J. Juras; www.volksbund.de; IGI; AF)

Johanna Amalie Grudnick b. Taukitten, Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 29 Jan 1875; dau. of Friedrich Eduard Grudnick and Dorothea Wilhelmine Treptua; bp. 21 Apr 1923; m. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 25 Oct 1898, Wilhelm Gottlieb Pokern; 6 children; d. Königsberg 10 Jun 1940 (FHL Microfilm 245255, 1930/

Franz Helmut Holdau b. Wuppertal-Elberfeld, Rheinland, Preussen 5 or 7 Jun 1916; son of Franz August Holdau and Anna Heischeid; bp. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 29 Nov 1942; conf. Königsberg 29 Nov 1942; m. Königsberg 5 or 12 Jun 1943, Ruth Ursula Freimann; rifleman; d. near Ladogasee, Russia 3 Aug 1943; bur. Michajlowskij, Russia (J. Juras; www.volksbund.de; IGI; AF)

Kuno Jenchewski b. Koenigsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 14 Apr 1926; son of Emil Gustav Jenschewski and Marie Amalie Blum; ord. priest; k. in battle Berlin, Preussen Apr or May 1945 (Marie Berger; Erika Jenchewski Koch)

Hans Gerhardt Klettke b. Posen, Posen, Preussen 8 Sep 1918; son of Edmund Ludwig Klettke and Salomea Antkowiak; bp. 11 Dec 1926; m. Berlin, Preussen 4 or 12 Jul 1942, Gerda Kuhn; non-commissioned officer; d. 2 km northwest of Heilsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 4 Feb 1945 (www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Rudi Heinz Knauer b. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 14 Oct 1918; son of Gustav Hans Knauer and Auguste Hedwig Lindtner; bp. 25 Aug 1925 or 27 Aug 1927; ord. deacon; m. Königsberg 15 Jul 1943, Edith Erna Jenschewski; d. 30 May or Jun 1944 (FHL Microfilm 271380, 1935 Census; IGI)

Alfred Hermann Knop b. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 15 Jun 1904; ord. priest; m. Herta Charlotte Hennig; 4 children; d. Königsberg 28 Apr 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 23, 8 Jun 1941, 92; FHL Microfilm 271380, 1935 Census)

Ernst Rainer Otto Lemke b. Rauschen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 28 Jul 1944; son of Otto Ernst Lemke and Edith Lina Meyer; d. dysentery Cottbus, Germany 4 Aug 1945 (IGI)

Otto Ernst Lemke b. Fischhausen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 6 Mar 1909; son of Carl Hermann Lemke and Wilhelmine Rosine Gemp; bp. 6 Aug 1927; m. 18 Jun 1943, Edith Lina Meyer; 1 child; lance corporal; k. in battle near Alt-Radekow, Brandenburg 23 Apr 1945 (Berlin civil registry 3 Jun 1948; IGI)

Berta Marie Nitsch b. Borchersdorf, Ostpreussen, Preussen 10 Feb or Jul 1884; dau. of Carl August Nitsch and Henriette Mundzeck; m. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen Oct 1902, August Hermann Martin; 5 children; 2m. Otto Friedrich Riegel; 3 children; d. Königsberg 15 or 16 Apr 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, No. 22, 1 Jun 1941, pg. 88; FHL Microfilm 271403, 1935 Census)

Werner Walter Rzepkowski b. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 17 Jan 1920; son of Richard Rzepkowski and Ella Friedericke Rock; bp. 18 Jun 1929; d. 1 Nov 1943 or 31 Dec 1945 (IGI; AF)

Kurt Rudolph Sprie b. Gutenfeld, Ostpreussen, Preussen 10 Nov 1906; son of Robert Emil August Sprie and Kaethe Bertha Ritter; bp. 13 Aug 1915; ord. teacher; d. 1943 (FHL Microfilm 245272, 1935 Census; IGI)

Siegfried Robert Konrad Paul Sprie b. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 20 Jan 1925; son of Konrad Erich Sprie and Klara Frieda Sommer; bp. 15 Sep 1934; airman; d. Radymno, Jaroslau, Poland 22 Jul 1944 (FHL Microfilm 245272, 1935 Census; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Harry Willi Waldhaus b. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 2 Apr 1926; son of Wilhelm Karl Waldhaus and Gertrud Minna Kaminski; bp. 8 May 1937; soldier; k. in battle Olsany 10 Sep 1944 (W. Kelm; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Wilhelm Karl Waldhaus b. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 20 May 1901; son of Friedrich Waldhaus and Johanna Friedericka Lupp; bp. 24 Jul 1937; m. Königsberg 2 Dec 1922, Gertrud Minna Kaminski; 3 children: k. by artillery Berlin, Preussen 27 or 28 Apr 1945 (W. Kelm; AF)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Ingrid Freimann Juras, Irmgard Freimann Klindt, and Ruth Freimann Dietz, interview by the author in German, Salt Lake City, March 23, 2007; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[3] Reinhard Freimann, interview by the author in German, Hanover, Germany, August 6, 2006.

[4] Renate Klein and Sigrid Klein, interview by the author, St. George, Utah, October 9, 2006.

[5] Inge Grünberg Seiffer, interview by Jennifer Heckmann in German, Backnang, Germany, August 17, 2006; summarized in English by the author.

[6] The twelfth article of faith of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints reads thus: “We believing in being subject to kings, presidents, rulers and magistrates, in obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law.”

[7] Erika Jenschewski Koch, interview by Michael Corley, Bountiful, Utah, March 14, 2008.

[8] Christel Freimann Schmidt, telephone interview with Judith Sartowski, February 25, 2008.

[9] Karin Kremulat Bryner, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, February 2, 2007.

[10] “Freimann Family History” (unpublished, 2001), 12; private collection.

[11] Gudrun Hellwig Weber, interview by the author in German, Schwerin, Germany, August 17, 2006.

[12] Maria Bresilge Berger, Erinnerungen (unpublished history, 1979), 12; private collection; trans. Renate Berger.

[13] Helga Kremulat Freimann, interview by Michael Corley, West Valley City, Utah, March 21, 2008.

[14] “Freimann Family History,” 17.

[15] Fritz E. Bollbach, Fate Rules My Life (Fritz E. Bollbach, 1993), 137–39.

[16] Mission leaders had also recommended that the members in the eastern districts—at least the women and the children—move west to areas in the districts of Chemnitz and Zwickau.

[17] Margarete Hack Hellwig, report (unpublished); private collection; recorded by Wilford Weber.

[18] No official passenger records were kept for the fatal voyage, but estimates run as high as 9,000 deaths; retrieved October 30, 2008, from http://

[19] Maria Bresilge Berger, Erinnerungen, 14–15.

[20] Ibid., 15.

[21] Ibid.

[22] Bollbach, Fate Rules My Life, 142, 153.

[23] Ibid., 161.

[24] Ibid., 163–64.

[25] Theodor Berger to Maria Bresilge Berger, letters; private collection.

[26] Bollbach, Fate Rules My Life, 169.

[27] “Freimann Family History,” 17.