Introduction

Historical Background

Members of the Schneidemihl Branch in about 1932, shortly before the Boy Scout program in Germany was forbidden by Hitler's government. The scout leader is Johannes Kindt (first row at left), who later became the district president. (W. Kindt)

Members of the Schneidemihl Branch in about 1932, shortly before the Boy Scout program in Germany was forbidden by Hitler's government. The scout leader is Johannes Kindt (first row at left), who later became the district president. (W. Kindt)

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints has a fascinating history that spans more than 170 years and includes peoples of every continent. The missionary effort that began in the German states in the 1840s resulted in the establishment of branches of the Church in virtually every corner of that land by 1900. Though many converts in Germany and Austria chose to immigrate to the United States, others remained in the fatherland to help the Church grow and prosper there. However, given the religious, cultural, and political traditions of this relatively young Germany (officially established in 1871), being a Latter-day Saint in the country was not easy.

Joining the Church in central Europe made German Latter-day Saints outsiders in their native country. They no longer worshipped with their Catholic or Protestant neighbors, business colleagues, school comrades, or best friends. Even in their new church, they may have felt like second-class citizens. Instead of wards and stakes, they were organized into branches and districts. Instead of listening regularly to prophets, apostles, seventies, and bishops, they received instruction mainly at the hands of mission presidents and young missionaries from small towns and farms in the American West. Instead of meeting in beautiful neighborhood churches with park-like surroundings, they gathered in taverns, apartment houses, or renovated factory rooms in the smoky industrial districts of large cities.

Nevertheless, they worshipped the same Heavenly Father, prayed in the name of the same Savior, studied the same scriptures, supported the same missionary program, and lived and preached the same gospel to their neighbors as their fellow Saints who lived in the United States.

Emigration to North America before and after World War I (1914–18) had weakened large branches in Germany and Austria and in some locations had made smaller branches defunct. As in other European countries, Latter-day Saint branches in Germany were constantly “starting over.”[1] However, as the history of the Church in Germany approached its centennial mark in the late 1930s, emigration had essentially stopped, missionary work had increased, and the branches of the East German Mission (Berlin) and the West German Mission (Frankfurt am Main) were strong and growing slowly. Unfortunately, World War II would seriously weaken the Church in Germany and end for decades its presence in eastern German territories that became part of post–World War II Poland and the Soviet Union.

The mission of the Church in Germany and Austria in 1939

The mission of the Church in Germany and Austria in 1939

Latter-day Saints in Germany during the Hitler era (1933–45) found themselves subjected to a unique set of challenges. For the first time, large numbers of Latter-day Saints were subjects of a totalitarian regime.[2] Under a government that convinced or compelled more and more of its citizens to march to the same dark tune, members of a church that exalted the concepts of freedom of choice and moral agency were bound to feel at odds with the party line. When Hitler’s armies achieved bloodless conquests of Austria (1938) and parts of Czechoslovakia (1938 and 1939), some Latter-day Saint Germans saw a war coming. By the time the German army invaded Poland on September 1, 1939, Germans were no longer allowed to emigrate. Thirteen thousand Latter-day Saints were trapped and compelled to share the fate of their 80 million countrymen. What happened to them by the time Germany surrendered on May 8, 1945, is tragic, and for some of them, although the war had ended, their tribulations were far from over. But how these faithful Saints reacted to the events of the time is inspiring.

Telling the Story

The history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (the LDS Church) in Gemany during World War II has never been written in more than a few pages. Gilbert Scharffs devoted a chapter to the topic in his book Mormonism in Germany.[3] A few dozen books have been published by eyewitnesses, and those books give excellent detail about the lives of individual Latter-day Saints in specific towns and branches, but most were written for family members and remain essentially unknown.[4] Several diaries written during the war years have survived, but none have been published.[5] Many survivors have written short accounts of their experiences; few of these have ever found their way into print, though some have been submitted to the Family History Library and to the Church History Library in Salt Lake City.

In 1974, I began to focus my interest on the history of the Church in Germany. From a review of the wartime issues of the Church magazine Der Stern, it was clear to me that the Church suffered heavy losses during the Third Reich. I began asking questions to which nobody had ever researched the answers: How many members in Germany and Austria died from 1939 to 1945? How many priesthood holders were lost? How many branch meeting places were damaged or destroyed? How many Latter-day Saint families lost their homes? What happened to the branches in territories later ceded to Poland and the Soviet Union? What happened to Primary classes, Relief Society work meetings and bazaars, and Young Women and Young Men programs? How was the missionary effort sustained, if at all? Answers to these questions will be found in the pages of this book.

This story needed to be told—not in general, but in sufficient detail that the experiences of members of every branch of the Church in Germany and Austria could be described. Why had this not been done in the six decades since the end of the war? This one question I can now answer, after thirty-three years of thinking and planning and three years of intense investigation. The effort required to write such a history is enormous and daunting. Such a story could be composed only after years of research and with the help of talented student assistants.

Interest in such a history is great. There could currently be as many as forty thousand members of the Church who have served missions in Germany and Austria. At least two hundred fifty thousand Latter-day Saints and others are related to the persons whose stories are featured in this history. The possibility that a German soldier in a photograph taken during the D-day invasion in 1944 could have been a priest from the Darmstadt Branch or that a Relief Society president might be among the dead in the aftermath of the Dresden firebombing of 1945 might motivate readers of World War II history books to think about the conflict from a different perspective.

In 2003, when Brigham Young University invited me to join the faculty of Religious Education as the instructor of Germanic family history, I realized that I now had the opportunity to write this history. I knew that nobody had attempted such a work, and I was more convinced than ever that it must be done. Finally, these faithful members of the Church—living or deceased—would have the chance to tell their stories.

My goal from the beginning has been to describe in great detail the lives of typical Latter-day Saints. Rather than an investigation of the relationship of the Church with the government of Hitler’s Germany or the National Socialist (Nazi) Party, this is the story of everyday Saints. How did they maintain a testimony of the everlasting gospel under conditions few Church members have ever experienced? How did they conduct worship services without priesthood holders, locate each other after air raids, support each other after they lost their homes and loved ones? The remarkable stories they tell answer such questions.

When all foreign missionaries were evacuated from Germany and Austria in August 1939, the leadership of the Church was placed in the hands of local members. All contact with Church leadership in Salt Lake City was lost when the United States was drawn into the war in December 1941. How did the leaders of the East and West German Missions administer the affairs of the Church? How did they communicate with district and branch presidents? Did they continue to hold conferences, print and distribute literature for instruction, keep membership records, promote genealogical research, do missionary work? These matters are described within the stories of eyewitnesses quoted here.

Compiling the Data

In order to present this history from the perspective of first-person experience, my assistants and I set out initially to interview all available surviving eyewitnesses, to locate biographies and autobiographies by and about eyewitnesses, and to study all available documents produced by Church units in the East and West German Missions. It was also decided early on that this history should be augmented with photographs, maps, and historical documents depicting the lives of the Latter-day Saints described in the pages of this book. To accomplish some of these goals, we needed the assistance of many individuals as well as the public media.

We immediately began assembling lists of survivors by conducting interviews with people we already knew and asking them to share with us the names of their living relatives and friends. Our list eventually grew to nearly five hundred persons (of the nearly thirteen thousand members of the Church in the two missions in 1939). Interviewees provided not only excellent first-person narratives regarding conditions and events in Germany during World War II, but also written stories of their own lives and the lives of deceased siblings, parents, and friends.

As we began our search for documents produced by Church units such as branches and mission offices, we were enthusiastically supported by the staff of the Church History Library in Salt Lake City. Church History Library call numbers appear in citations, such as CR 4 12, followed by the page number.

The Church News section of the Deseret News was kind enough to feature an introduction of our research on the cover of the February 11, 2006, issue, which coverage yielded more than three hundred responses from individuals wishing to share their stories or to recommend persons for us to contact. The same article was translated and featured in the German Liahona later that year and likewise attracted many responses from readers in Germany and Austria.

Organizing the data collected was, of course, a major challenge. The most efficient way proved to be the storage of data under the name of the branch to which each member belonged on September 1, 1939, when the war began. Hundreds of Saints, including displaced members and returning soldiers, had changed their branch affiliations by the time the war officially ended on May 8, 1945, and in the years that followed. The archival collection that emerged is monumental and will likely be transferred to the Harold B. Lee Library of the Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah.

The Status of the Church in Germany and Austria at the Onset of World War II

| 1939 | East | West |

| Elders | 402 | 390 |

| Priests | 194 | 179 |

| Teachers | 243 | 161 |

| Deacons | 445 | 345 |

| Other Adult Males | 1,245 | 939 |

| Adult Females | 4,336 | 3,172 |

| Male Children | 384 | 329 |

| Female Children | 358 | 280 |

| Total | 7,607 | 5,795 |

| Mission | East (Berlin) | West (Frankfurt am Main) | Total |

| Districts | 13 | 13 | 26 |

| Branches | 75 | 69 | 144 |

From reports compiled in the years before World War II, quite a lot is known about the membership of the Church in the two German missions.[6] The missions were similar in population and in geographical size (see map above).[7] No stakes of Zion had been established in Europe by 1939; members were organized instead into districts and branches. Each German mission had thirteen districts, and each district included from three to ten branches. The largest district in either mission was Berlin (East German Mission) with ten branches and 1,270 members. The smallest district was Hindenburg (East German Mission) with only four branches and sixty-five members.

The average size of a branch in Germany in 1939 was slightly more than one hundred members. Each branch had a presidency, clerks and secretaries, a Sunday School, a priesthood group, a Relief Society, a Primary organization, and youth groups. Each district had a presidency and clerks and leaders for each of the auxiliaries. Districts also had genealogical specialists, choir leaders, and in some cases recreational specialists.

The Largest LDS Branches in Germany in 1939 | ||

Branch | Membership | |

1 | Chemnitz Center | 469 |

2 | Königsberg | 465 |

3 | Hamburg-St.Georg | 400 |

4 | Dresden | 369 |

5 | Stettin | 359 |

6 | Leipzig Center | 328 |

7 | Nuremberg | 284 |

8 | Annaberg-Buchholz | 274 |

9 | Berlin Center | 268 |

10 | Breslau West | 265 |

In the two German missions, only one meetinghouse actually belonged to the Church—a modest but excellent structure erected in Selbongen, East Prussia (East German Mission), in 1929. The typical location for branch meetings was something far less prominent. Freestanding structures were very rare in the Church in Germany and Austria in those days. Most branches rented rooms in large buildings erected primarily for commercial use. Factories, warehouses, office buildings, and the like were sought out for space. Renovations were usually financed by the branch and resulted in chapels of appropriate size. In most cases there were also two or more classrooms. Most branch facilities featured restrooms and a cloakroom, but there was almost never an office for the branch presidency or the clerks. Some locations included a cultural hall, but most cultural activities took place on a stage or a rostrum in the main meeting room. Most chapels were used during the week for auxiliary meetings.

Decorations in branch chapels were sparse and modest. In most cases, one or two pictures were hung on the walls. The Savior was the most common subject of those pictures, but contemporary photographs also show small depictions of the Salt Lake Temple and the Prophet Joseph Smith or photographs of then Church President Heber J. Grant. The phrase “The Glory of God Is Intelligence” was often seen painted on the wall of the chapel, on the pulpit, or even on embroideries somewhere at the front of the room.

Church meetings for smaller groups were usually held in private homes and attendees could number as high as thirty. This became progressively more common as branches lost their meeting rooms in air raids as the war drew to a close. In 1945, schools became popular meeting venues, and in such cases no signs of the presence of the Church were visible.

District presidencies had no specific physical locations or offices. Instead, district leaders conducted their business in the rooms of local branch buildings or in their own homes. Each mission rented office space in an affluent neighborhood, the East German Mission at Händelallee 6 in Berlin and the West German Mission at Schaumainkai 41 in Frankfurt am Main.

The standard meeting format in a branch was similar to that of branches and wards in other countries: Sunday School was held on Sunday morning; sacrament meeting took place in the late afternoon or evening; and meetings for the Relief Society, priesthood groups, and the Mutual Improvement Association (MIA) were held on evenings during the week. In most branches throughout the two missions, the Primary organization for children held meetings on Wednesday afternoons, mostly because public schools in Germany dismissed by 1:00 p.m. on Wednesdays. German Saints have traditionally sung the hymns of Zion with great enthusiasm, and choirs were integral parts of German branches and districts. Choir practice was usually held weekly on a convenient evening.

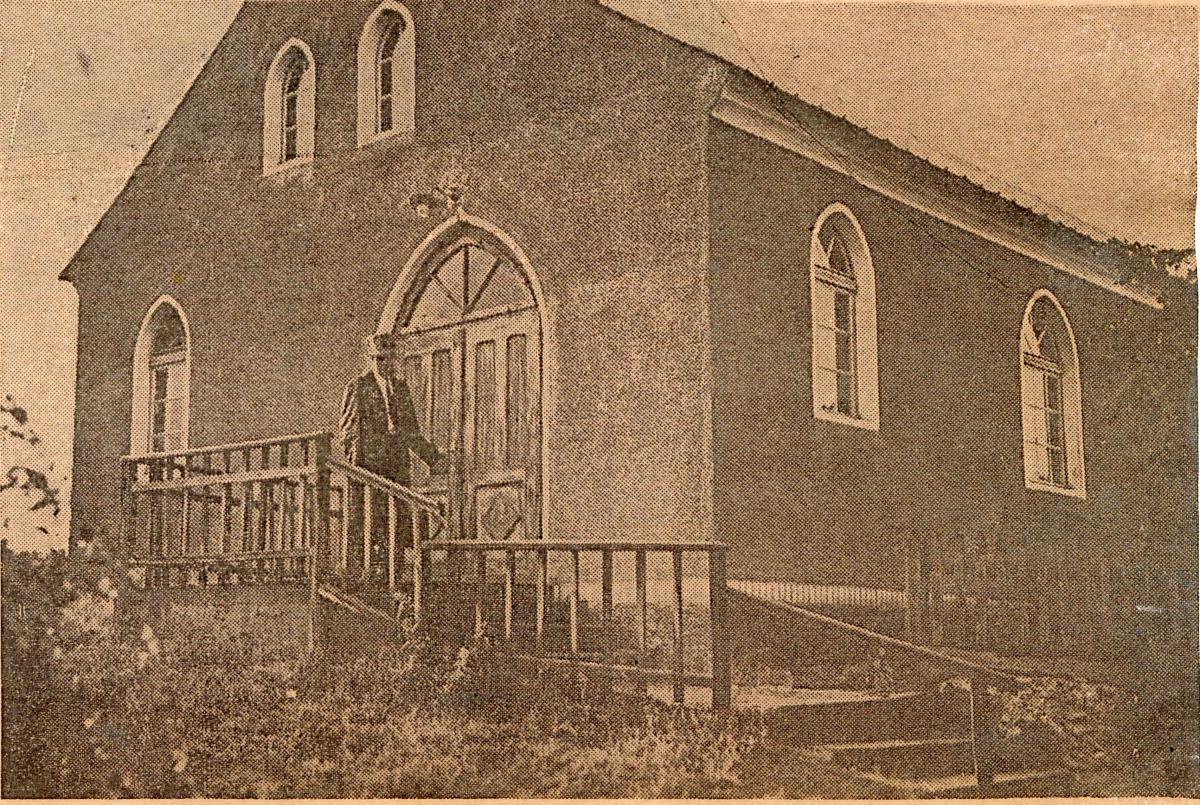

The Selbongen Branch building was constructed in 1929. During World War II, this was the only structure owned by the Church in Germany. The Polish name of the town is Zelwagi, and the building is currently owned and used by the Catholic Church. (Deseret News, 1938)

The Selbongen Branch building was constructed in 1929. During World War II, this was the only structure owned by the Church in Germany. The Polish name of the town is Zelwagi, and the building is currently owned and used by the Catholic Church. (Deseret News, 1938)

Semiannual conferences were an important and popular part of Church life in Germany in 1939 and throughout most of the war. Mission conferences were common before the war but could not be held later in the war because of restrictions in travel and resources. Each district held semiannual conferences and each branch held from two to four conferences each year. In addition, Sunday School and other auxiliary conferences were prominent events. The largest events were district conferences; some lasted from Friday through Sunday and included concerts, dances, and performances by choirs, orchestras, and theatrical groups. These were exciting affairs that drew hundreds of members who in turn often brought their nonmember friends.

German Latter-day Saints as Citizens under Hitler

Adolf Hitler and his National Socialist (Nazi) Party came to power in January 1933. In August 1934, German president Paul von Hindenburg died, and Hitler combined the offices of chancellor (which he had acquired legally) and president. By 1935, he outlawed the Communist Party and neutralized all other political parties, which gave him control of the parliament (Reichstag). He also won the loyalty of the German military by strengthening the army and the navy and establishing an air force—all in contradiction to the Treaty of Versailles, which had severely restricted the German military following World War I.

In Hitler’s Third Reich, Latter-day Saints in Germany and Austria (which was annexed by Germany on March 12, 1938) were expected to be model citizens just as all other Germans. In other words, Saints were to be Germans first and to have no secondary allegiance. Nazi Party programs were developed for every member of society old enough to say “Heil Hitler!” By 1936, everybody was encouraged—and some strongly pressured—to join the appropriate Nazi organization; there were distinct groups for men (Sturmabteiling), women (Frauenbund), boys (Hitlerjugend), girls (Bund Deutscher Mädchen), athletes (Sportbund), truck drivers (Kraftfahrerkorps), teachers (Lehrerbund), and so forth. Each group had its own uniform and insignia; it was difficult to avoid every one of them. Nevertheless, many adult Latter-day Saints were able to slip by without associating with the Party, often by making excuses about spending their free time in some kind of humanitarian service.

The two prevailing faiths—Catholic and Protestant—comprised more than 95 percent of the German population in that era. Many smaller churches also existed in Germany but were not considered to be large enough to warrant concern; Latter-day Saints fell into this category. The two major churches were too powerful to be successfully attacked by the Nazi Party, while the smaller ones (commonly called “sects”) were disregarded by both the government and the common people. The small number of Latter-day Saints in the Third Reich (just over thirteen thousand among a population of 80 million) may have been an advantage in this regard because Church units were never large enough to attract attention. Indeed, in many cases, their meeting rooms were often located in Hinterhäuser, or buildings behind main structures. Signs identifying the existence of the Church were usually small and unobtrusive. One usually had to be an insider to know that the Church existed in a given town or city.

One of the most visible ways in which a citizen could perform his or her civic duties was in the military. Perhaps as many as 1,800 Latter-day Saints in Germany and Austria performed active military service between 1939 and 1945, though few ever volunteered. Many more served in reserve units, including hundreds who had served in the German army in France or Russia in World War I. There was no provision for civil service as an alternative to military service in Hitler’s philosophy, and there was no tolerance for any who wished to declare himself a conscientious objector.[8]

Community service was common among citizens in Nazi Germany, and Church members were often consistent and willing participants. They collected used winter clothing for soldiers at the front, dutifully stood in line to receive their ration cards, hurried to fight fires and rescue buried victims after air raids, and took refugees into their homes when other housing was not to be found. Of course, those functions were carried out by Germans of all religious persuasions who simply believed in helping because it was the right thing to do.

In a negative sense, being a good citizen in the Third Reich also included assisting the government in identifying and apprehending those persons who were considered enemies of the state—principally Jews. Several eyewitnesses interviewed in connection with this study remembered scenes of destruction after the “Night of Broken Glass” (Reichskristallnacht, November 9–10, 1938), when organized Nazis raided Jewish stores and invaded Jewish homes. Some eyewitnesses later saw Jewish neighbors and friends being taken away in trucks, but—as most Germans of the day—had no idea what terrible treatment awaited those Jews under the secret German program termed the “Final Solution of the Jewish Question” (the murder of European Jews). Several Latter-day Saints decided for one reason or another that obedience to Hitler and his state was not required of a good member of the Church. Several of these Saints died in concentration camps, and several more spent time there.[9]

The Socioeconomic Status of Latter-day Saints in the Third Reich

As they had for decades, Church members in the Hitler era belonged for the most part to the lower middle class. Many men were skilled laborers of the artisan classes, having learned a trade through an apprenticeship lasting from two to four years. A small number were masters in their trades and crafts. In only a few cases were Latter-day Saints in management positions, and there were few, if any, professionals such as physicians, attorneys, and teachers. For example, mission supervisor Herbert Klopfer was a translator and office worker, while his counselors Richard Ranglack and Paul Langheinrich worked in a hotel and in a government genealogical research office respectively.

Several members owned their own shops, such as Walter Krause, a carpenter in the Frankfurt-Oder Branch, and Friedrich Birth, a glazier in the Schneidemühl Branch. Several were small entrepreneurs, including Fritz Fischer, whose modest fleet of trucks and wagons transported manure from the streets of Berlin to the countryside, and Fritz Lehnig of the Cottbus Branch, who ran a wholesale vegetable business. Rare was the Church member who enjoyed a high rank in business or industry, as did Fritz Mudrow of the Berlin Schöneberg Branch (an administrator in the national labor force) and Karl Binder of the same branch (an engineer and manager in an armaments plant in Berlin).

Because the gospel had been preached primarily in the cities in Germany, very few Latter-day Saints in the Nazi era were farmers. It was simply too difficult to travel to church on Sundays from far away. (The branch in Selbongen, East Prussia, is a marked exception.) Although many Latter-day Saint families lived in multistory apartment buildings, they often rented garden space at the edge of town and kept animals such as chickens and goats. On the other hand, stories of dogs and cats are not common; no eyewitnesses recalled problems with feeding and protecting pets.

According to the testimonies of surviving eyewitnesses, most Latter-day Saint women were homemakers. When the German economy experienced boom years in the late 1930s, great emphasis was placed on occupational training for girls in the schools. Most teenage Latter-day Saint girls prepared for gainful employment in the Hitler era while their mothers often remained in the home. However, the war compelled a change in status for many of the homemakers when they were required by the government to assume jobs vacated by men who were drafted into the military. Most such jobs were in the blue-collar sector.

Very seldom did a Latter-day Saint family own a single-family dwelling. Only a few were wealthy enough to employ domestic servants, own an automobile, or have a telephone in the home. Most had indoor plumbing, but families often shared a restroom at the end of the hallway with their neighbors. Eyewitness stories about carrying water from the neighborhood well are ubiquitous, and that necessity became more common as city water lines were destroyed.

Ration Coupons and Shortages in Wartime Germany

As in most nations heavily involved in World War II, ration coupons were an integral part of life in Germany even before the war began in 1939. Restrictions on most food and luxury items were constant. Specialty items generally disappeared from public view. Standing in lines to redeem food coupons took up large portions of the day, and families often split up to accomplish the task: the mother went to the butcher, one child to the baker, another child to the green grocer, and so forth. However, a ration coupon was no guarantee that the item was actually available. It was a common occurrence that a store ran out of the item and the owner came out to announce to those still in line that there was no more of the foodstuffs they wanted—or he simply closed the door and hung out the geschlossen (closed) sign.

Toward the end of the war, the German government accomplished near miracles in keeping food distributed equitably throughout the country. Still, ration lines became ever longer and stories are commonly told of women who refused to leave the lines when the air-raid sirens sounded; they preferred to believe that the raid would not come to their neighborhood, which allowed them to complete their purchases and feed their families. Essentially all eyewitnesses who lived in large cities in Germany and Austria reported that they had enough food until the very day the enemy arrived in their neighborhood. At that point the food system broke down totally and starvation threatened their existence.

Transportation in the Third Reich

Germany’s public transportation systems were excellent during the Nazi period, built for densely populated areas where personal automobile ownership was a rarity. Latter-day Saints often tell of traveling to Church meetings on the bus or the streetcar, but some chose the longer walking time because they lacked money for the streetcar. Railroad service across the Reich featured only steam locomotives, but some traveled at very high speeds, and timetables were strictly observed during the first years of the war. Latter-day Saints report that there were no general restrictions on travel away from home during most of the war years, though some trains were full of troops, which meant civilians had to wait for later connections. Travel by train often took longer than usual as water and coal supplies waned, tracks and bridges were destroyed, and various branches of the government and the military competed for the use of an ever-decreasing number of trains.

When attacks from the air and invading armies caused the destruction of the trains and the tracks, schedules were obviously interrupted and travel became unreliable. People rode in whatever conveyances were available, often in boxcars or cattle cars. During the final year of the war, the railroads frantically conveyed fresh soldiers to the front and wounded soldiers and refugees to the rear. According to eyewitnesses, it was no longer necessary to purchase tickets; instead, passengers fought their way onto the trains—many climbed through windows to get in. Refugees were often compelled to discard their luggage in the scramble to board a train.

Because they were prime targets for attacks, most railroad stations had air-raid shelters. Trains moving down the tracks or standing on sidings were under constant attack during the last year of the war, when the German Luftwaffe (air force) could no longer provide sufficient defense. Many Latter-day Saints were in trains attacked by fighter planes and several lost their lives in such attacks.[10] At the end of the war and for months afterward, people rode trains under dangerous circumstances; sitting on the roof, standing on the running boards, or clinging to other parts of the train were common means of riding along.

By the end of the war, bus and streetcar transportation had been seriously interrupted or curtailed in most German cities. Now and then, a streetcar would run for a few blocks, then passengers would get off and walk down the line for a few blocks, where the service would continue again. In cities with subway systems (Untergrundbahn, or U-Bahn), some of the lines survived below the streets and U-Bahn stations were commonly used as air-raid shelters.

Of the few Latter-day Saints who owned automobiles or trucks, most used them in association with businesses. Many of those vehicles were destroyed in air raids. During the last days of the war, surviving personal automobiles were usually seized by the government, the military, or the invaders; personal property was no longer protected.

Eyewitnesses recalled walking long distances from home to school and church; walking times of more than one hour in one direction were not uncommon. For persons in good health, walking was no hardship in Germany in those days. Indeed, many branch outings involved wandern, the tradition of walking all day through forests outside of town and enjoying a picnic along the way. Some eyewitnesses told of being baptized in forest ponds, and branch members walked nearly an hour each way at all seasons of the year to witness the ceremonies.

Schools in Nazi Germany

The complex and respected German school system, which dates back to the 1870s, was expanded and improved during the early twentieth century. However, Allied air attacks did not spare schools; programs were often interrupted, abbreviated, or cancelled, and graduations were routinely postponed. Some schools in larger cities served double duty, accommodating children from bombed-out schools in split sessions. Many LDS eyewitnesses recalled that the official school starting time was delayed by an hour or two on any morning following a night interrupted by an air raid.

Several eyewitnesses recalled having teachers who were enthusiastic Nazi Party members (all teachers employed by the state were required to join). Some told of singing the “Deutschlandlied” (German national anthem) or the “Horst-Wessel-Lied” (the official Party hymn) every morning. Others recalled that army-like inspections were conducted to insure the students’ clothing was in order, their hair combed, and fingernails clean, and that punishments were administered when an order was not followed.

Entire classes of school children were sometimes moved from larger cities to rural areas as part of the children’s evacuation program (see “Kinderlandverschickung” in the glossary). Many teachers were sent with their homeroom classes to a distant small town to continue instruction away from the air raids. When schools were damaged or transformed into hospitals later in the war, the children were often pleased at first. Later, however, they learned of the disadvantages of a lack of formal instruction.

Religious instruction was provided for Catholic and Protestant students for the first eight grades of public school. Latter-day Saint children were allowed to choose between these two religions (where both were available) or to not attend at all. There are no reports of programmatic persecution of LDS students in public schools, though confrontations with fanatic Nazi teachers did occur now and then.

Even before the war, most German students left public schools after the eighth grade to pursue an apprenticeship or employment. Few continued formal education, with less than 10 percent planning on attending the university. The great majority of LDS youth did not or could not pursue higher education.

Air Raids over Germany

As early as the first week of the war, Polish airplanes attacked cities in the German Reich. By 1941, British air raids were launched against most large German cities—especially in the western part of the nation. When the United States joined the war in the European Theater in 1942, the Allied bombing campaign became better coordinated and a standard procedure was developed: the British Royal Air Force conducted their raids under cover of night and the American Army Air Corps flew during the day. In some cities, air raids were rare, perhaps even unique. In others, especially where critical war industries were located, raids were more frequent. During 1944, the most important cities were subject to raids every week. Because many large cities in Germany were just a few miles apart, enemy airplanes flying in one direction of the compass had to be considered to be on their way to one of several cities. Alarms were sounded in all possible target cities; in many communities, false alarms were more frequent than actual attacks.

Even in large cities, Germans seldom had access to official, heavy concrete bunkers for refuge from enemy attacks. In large cities, many bunkers were constructed in parks, in or near railroad stations, and near large intersections. Still, nowhere were there enough bunkers to shelter everyone. Typically Germans simply sought refuge in their own basements. Of course, those basements had not been constructed to protect people from five-hundred-pound “blockbuster” bombs, but residents did what they could to fortify the ceilings and walls of their basements. In most cases, entry and exit were through the main hallway or stairway serving the entire building. Shelters in a variety of public buildings and even large private or commercial buildings were clearly marked as Luftschutzraum or LSR and were open to all (see the Zwickau Branch chapter).

Air raid warnings were announced by civil defense officials with loud wailing sirens. Three different signals were used: one to announce a possible attack, one for a probable or imminent attack, and one for the actual arrival of attackers over the city’s air space. The interim between the first and the last alarms was from ten to twenty minutes or more. Thus there was usually time for people to find shelter, even if it was away from home. Proof positive of a pending strike was seen in the form of illumination flares dropped above the target by advance enemy airplanes. Called Christbäume or Weihnachtsbäume (Christmas trees) by the Germans, those flares were visible from miles away and heralded death and destruction. Civil defense units sometimes responded by burning decoy flares to mislead the attackers.

Every neighborhood had an air-raid warden. Wardens were sometimes auxiliary policemen, but most often were low-ranking members of the Nazi Party. When the air-raid sirens sounded, it was their job to see that people vacated their apartments, public buildings, and streets and sought refuge in the shelters. They also reminded people to close their blinds or turn off their lights to achieve total blackout. Heavy fines were levied against violators of this safety standard. It was also the air-raid warden’s responsibility to see that all entries to shelters were closed and locked when the final siren was heard. Persons not yet in shelters were then on their own to find alternative places of protection. For a variety of reasons, some people chose to stay in their apartments rather than go to the shelter. In reality, the chances of survival were almost equal wherever they were. On the streets, however, they could be killed by enemy bombs as well as by shrapnel from friendly antiaircraft guns used to shoot down the attackers.

Latter-day Saint eyewitnesses tell of preparing for air raids the same way their neighbors prepared. All but the smallest children were expected to carry a valise or a suitcase with the most important survival items as they descended into the basement or hurried down the street to a public shelter. One of the parents usually carried the most valuable family documents, including genealogical papers, family photographs, and books of scripture. Most brought a change of clothing and enough food for the next few hours. There was little time to worry about what was left behind.

Life in the typical air-raid shelter was little more than survival. Some tried to sleep (which was usually impossible because of the noise), while others prayed, read newspapers, or played cards (if there was enough light to do so). Parents tried to entertain or comfort their children. Some sat on chairs, others on the floor—usually in rooms that lacked proper heating or cooling systems. Most were exhausted from lack of sleep and wanted only to return to their homes.

Three means of self defense were practiced everywhere people gathered in private shelters. First, because apartment houses in most cities were built with no space between them, the basements of any two adjacent apartment buildings usually shared a common wall. Residents were instructed to make a hole in the wall (Mauerdurchbruch) large enough for an adult to crawl through.[11] If the exit of one basement was blocked, the people could escape through that wall into the next basement by simply removing loose brick or temporary wood structures. Another standard feature in each shelter was one or more barrels of water; if fires had broken out close to the escape route, each person could soak a blanket in the water and put it over his head to prevent suffocation or burns as he or she exited the shelter. Finally, the contents were removed from the attic of each house to provide less material for combustion and to make it easier to find and remove incendiary bombs. Such bombs often penetrated the roof and came to rest on the floor of the attic. The timer fuses usually did not initiate fire for several minutes, allowing residents who kept supplies of sand and water in the attic to smother the bombs before they began to burn or to douse smaller fires before they spread.

When the all-clear siren sounded, air-raid wardens moved to evacuate the shelters as fast as possible. The main purpose of this was to prevent the occupants from suffocating in the shelters when smoke became thick or firestorms ensued. In crowded neighborhoods with tall apartment buildings, fires that started in the upper floors soon spread downward and to adjacent buildings. The oxygen feeding those fires was sucked out of the environment, making it hard to breathe. The upward rush of the air to the fire felt like wind and gave rise to the term firestorm. People emerged from the basements and ran down the street in search of open space where air was more plentiful. A technical description of firestorms is provided by author David Irving in a police report from the city of Hamburg:

An estimate of the force of this fire-storm could be obtained only by analyzing it soberly as a meteorological phenomenon: as a result of the sudden linking of a number of fires, the air above was heated to such an extent that a violent updraft occurred, which, in turn, caused the surrounding fresh air to be sucked in from all sides to the centre of the fire area. This tremendous suction caused movements of air of far greater force than normal winds. In meteorology the differences of temperature involved are of the order of 20° to 30° C. In this fire-storm they were of the order of 600°, 800° or even 1,000° C. This explained the colossal force of the fire-storm winds.[12]

Following air raids, the fortunate people were those who emerged from the shelters to find that there had been no attack at all. It was also a relief to learn that the damage done was to structures blocks away and that one’s own home was intact. However, this relief was often dispelled by the sound of another alarm siren a few hours later.

Culture and Entertainment in Nazi Germany

Despite the privations of the war years, motion picture theaters, opera houses, dance halls, and bars stayed open until they were destroyed or their utilities were cut off.[13] New movies were released and new hit songs were heard over the radio. Newspapers were printed in many cities until the day the Allied invaders arrived. Soccer games were played and citizens went ice skating, swimming, and hiking. Some Germans and Austrians even continued to take vacations (without leaving the country) for the first few war years. Birthday parties took place, christenings and weddings were celebrated in local churches, and clubs maintained their regular activities as long as possible. Local and national governments did their best to sustain the lifestyle of their citizens during the war and were remarkably successful in the effort. Of course, when the war came to an end and the conquerors ruled, life was reduced to mere subsistence, and entertainment was no longer a priority.

The End of Peacetime

When World War II began on September 1, 1939, the majority of Germans believed that Germany’s cause was just and that victory was likely if not certain. Many Latter-day Saints were of the same belief. But it is possible that members of the Church in Germany realized before other Germans that the war was not a just cause and that defeat and invasion were possible if not probable. This must have been a frightening prospect. Several decades ago, Douglas F. Tobler was told by several German eyewitnesses that they believed the prophecies of the Book of Mormon, namely, that any people fighting against the inhabitants of the promised land (North America) were doomed to ultimate failure.[14] Those eyewitnesses must then have had terrible premonitions when Germany and the United States exchanged declarations of war in December 1941.

Editorial comments:

In chapters in which an eyewitness provided a single interview or document, it may be assumed that all information attributed to that eyewitness was taken from the same source. This allows the elimination of hundreds of repetitious footnotes.

Many interviewees anglicized their names after immigrating to America. (For instance, the name Müller became Mueller.) This book will favor German spelling when citing interviewees’ experiences in Germany and anglicized spelling when citing experiences or interviews which occurred in the United States. This seeming inconsistency is not meant to confuse the reader, but to show proper respect to the people who have shared their stories.

Precise details regarding the sufferings of Latter-day Saints in the following pages have been summarized or even suppressed in some cases. Sufficient allusions are made to the fact that what happened was often much worse than expressed in my descriptions. The presentation of gruesome detail serves no worthy purpose in this book. It is not the goal of this book to emphasize the morbid, the heinous, the perverse, or the inhumane. What the Saints of the East German Mission experienced during World War II was often so terrifying and hideous that the reader may believe the many eyewitnesses who stated simply that “there are no words that could adequately describe what happened.” Of course, no such generalizations or simplifications have been made where quotations have been taken from interviews and written eyewitness accounts.

Notes

[1] Douglas F. Tobler, interview by the author, Lindon, Utah, July 25, 2008.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Gilbert Scharffs, “Mormonism Holds on during the World War II Years,” in Mormonism in Germany: The History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in Germany (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1970), 91–116.

[4] Excellent examples of the few published autobiographies are those of Werner Klein (Landsberg Branch, Schneidemühl District), Karola Hilbert (Berlin Neukölln Branch, Berlin District), and Gerd Skibbe (Wolgast Group, Rostock District).

[5] See the stories of Anton Larisch (Görlitz Branch, Dresden District and Halberstadt Group, Leipzig District), Alfred Bork (Stettin Branch, Stettin District), and sister missionaries Renate Berger (Königsberg Branch, Königsberg District), and Helga Meiszus Birth Meyer (Tilsit Branch, Königsberg District).

[6] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[7] Hitler’s Germany had about 80 million inhabitants in 1939 and was roughly the size of the state of Texas.

[8] The Jehovah’s Witnesses in Germany (known as die ernsten Bibelforscher) publicly opposed military service and as a group became inmates of prisons and concentration camps.

[9] See the stories of Elisabeth Elsa Jung Süss (Chemnitz Center Branch, Chemnitz District) and Bruno Stroganoff (Tilsit Branch, Königsberg Distruct).

[10] See the chapters on the Tilsit and Annaberg-Buchholz Branches for examples of such losses.

[11] David Irving, The Destruction of Dresden (London: Focal Point, 1974), 42.

[12] Ibid., 162.

[13] The Berlin Opera House was destroyed and rebuilt twice during the war. No attempt was made to restore it after the third time it was bombed and burned out.

[14] Douglas F. Tobler interview.