Insterburg Branch, Königsberg District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 288-94.

The city of Insterburg (now Chernyakhovsk, Russia) is located about thirty-three miles east of Königsberg, the capital of East Prussia. When World War II started on September 1, 1939, approximately 50,000 people lived in Insterburg, only forty of whom were Latter-day Saints.

| Insterburg Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 0 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 1 |

| Deacons | 0 |

| Other Adult Males | 7 |

| Adult Females | 31 |

| Male Children | 0 |

| Female Children | 0 |

| Total | 40 |

“Our branch was small, mostly a few old ladies and some children,” recalled Käthe Braun (born 1925). “While I was there, we didn’t have a Primary organization, MIA for young people, or Relief Society.”[2] Because the membership of the Insterburg Branch was dominated by adult females (78 percent), and there were officially no elders in the branch at the onset of the war, priesthood leaders from Königsberg came to visit and direct branch activities. Käthe recalled three of them: district president Max Freimann and his counselors, Brother Jenschewski and Brother Rzepkowsk—all from Königsberg.

The Insterburg Branch met in rented rooms at Erich-Koch-Strasse 15 on the main floor. Ruth Braun (born 1923), Käthe’s sister, recalled that “we had a curtain in the middle of the room, separating it so the adults could have one side of the room and the children the other. We were just a few families.” Albert Buntfuss (born 1926) recalled that one room measured about twenty by twenty-five feet in size.

Insterburg branch members outside of their meeting place (R. Braun Fricke)

Insterburg branch members outside of their meeting place (R. Braun Fricke)

Eyewitness accounts of life among the members of the Insterburg Branch come from two families—Braun and Buntfuss. Ruth Braun recalled that the branch president, a brother Jakulat, had passed away shortly before the war. The branch may have leaned upon visiting priesthood authorities for a while, but Alfred Buntfuss recalled that his father, Emil Alfred Buntfuss, was the branch president during the war: “He blessed and passed the sacrament” (which he could have done while not yet an elder).[3] Sunday School was the first meeting of the day, but the branch likely held no meetings during the week in those days.[4]

About his father, Alfred Buntfuss recalled the following:

Before the war, my father had to go to jail, and he was released four or five months later. A sister in the Church accused him because my father had told her husband that he could not have the priesthood. He was taken to prison because they thought he was a communist. . . . My father was against the regime. I knew that. We always listened to the English radio station, though it was prohibited.

Ruth and Käthe’s mother, Minna Braun, had been baptized in 1931. She was a very faithful member who was not ashamed to share the gospel with others. Käthe remembered how her mother always seemed to have a purse “stuffed full of missionary tracts.” She handed them out to people on their way to church meetings—a walk of nearly one hour. Sister Braun was sad when the missionaries left, which happened with no warning on August 25, 1939. According to Ruth, “When [the missionaries] were gone, it seemed like everything was different and we didn’t have any connection with Salt Lake City anymore.”

Insterburg branch outing (R. Braun Fricke)

Insterburg branch outing (R. Braun Fricke)

At that time, Käthe Braun was living on a farm about two hours by train south of Insterburg. Having finished her schooling, she was required to do a Pflichtjahr (year of government service) on a farm. She and seven other girls took the place of farm boys who had been drafted. “Nobody was thinking about war then,” Käthe recalled,

But we were close to the Polish border and suddenly things changed in our otherwise quiet neighborhood. Tanks rolled by, columns of soldiers in vehicles drove by. So many strange noises. This went on for about a week, then it was quiet again. This was a really scary time for us. We would all have rather stayed home with our families.

The chapel of the Insterburg Branch just before World War II (A. Buntfuss)

The chapel of the Insterburg Branch just before World War II (A. Buntfuss)

Käthe disliked farm work, so she was transferred to a different town to work as a domestic servant. She finished her year of service, then returned to Insterburg and found a job in a shop where uniforms were made. There she hoped to complete her occupational training.

Because her workplace was close to church, Käthe was given a key to the rooms and went there several times a week during her lunch hour to clean and dust so that things were in order for the meetings on Sunday.

Minna Braun’s eldest son, Fritz Wilhelm Braun, may have been the lone priest in the branch in 1939. He was killed in battle on September 6, 1941, at the age of twenty-seven. His sister Käthe later wrote, “When the army informed us that [Fritz] was dead, my father [Wilhelm Braun] wept. It was the first time I had ever seen him cry. He sat at the table, and tears ran down his cheeks.”

In his autobiography, Alfred Buntfuss wrote the following caption for a photograph of the branch members that was entitled “The last meeting—1941”

The end of the Insterburg Branch. The Mormons had been a thorn in the side of Hitler’s government for some time. The missionaries were long since gone. Members were in the military. My father was sent to Norway to work at a wharf. The building had belonged to a Jew who was in a concentration camp. The building was declared structurally unsafe.

After this time, the family of Alfred Emil and Gertrud Buntfuss and one other family took the train west to Königsberg about twice a month to attend meetings. It was expensive and involved a lot of travel time. Ruth Braun went north to Tilsit about once a month to attend meetings there. She enjoyed spending time with the Schulzke family in Tilsit.

The Church was fortunately not yet defunct in Insterburg. Alfred Bork, a soldier and member of the Stettin Branch, was stationed close enough to Insterburg to attend Church meetings there. His diary reported the following on April 5, 1942:

Visited the Insterburg Branch today at Spritzenstrasse. Not many members attended, but it was a wonderful time. Last week I searched for three hours before I found the meeting place.[5]

Brother Bork’s record does not indicate whether the branch had found new rooms or if the meetings were being held in the home of a member. One week later, April 12, 1942, he sought out the branch again:

No meeting today. Only every other week. Thanks to the war, there is no coal, at least not enough. And the branch leader comes from Königsberg. And there are so few members who attend. Today I visited the Sawatzki family at Cezilenstrasse 14.[6]

Insterburg Saints posed for this photograph after holding their last meeting in 1941 at Erich Koch Strasse. The sign on the wall to the right displays the name of the Church (A. Buntfuss)

Insterburg Saints posed for this photograph after holding their last meeting in 1941 at Erich Koch Strasse. The sign on the wall to the right displays the name of the Church (A. Buntfuss)

Apparently, the Saints in Insterburg were not about to give up on their church—despite no longer having an official meetinghouse. The January 1943 directory of the East German Mission showed that meetings were being held at Theaterstrasse 1 in the Jakulat home.[7]

Alfred Buntfuss was never an enthusiastic member of the Hitler Youth: “On the one hand the activities were a lot of fun but, on the other hand, I did not have a good feeling. I was the only Mormon in our Hitler Youth group.” Being the only Latter-day Saint in the neighborhood was not always an honor to a little boy. “Sometimes, in school or in our neighborhood they made fun of me and called me Mormone-Zitrone [Mormon lemon] but they never said anything worse.”

Boyhood ended for young Alfred in 1942. He went to Poland for a month of hard training under SS soldiers who had been wounded. After that, he was inducted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst. He was trained as a barber during the day and as an antiaircraft gunner at night. This was only the beginning of his service to the Reich. As he later wrote,

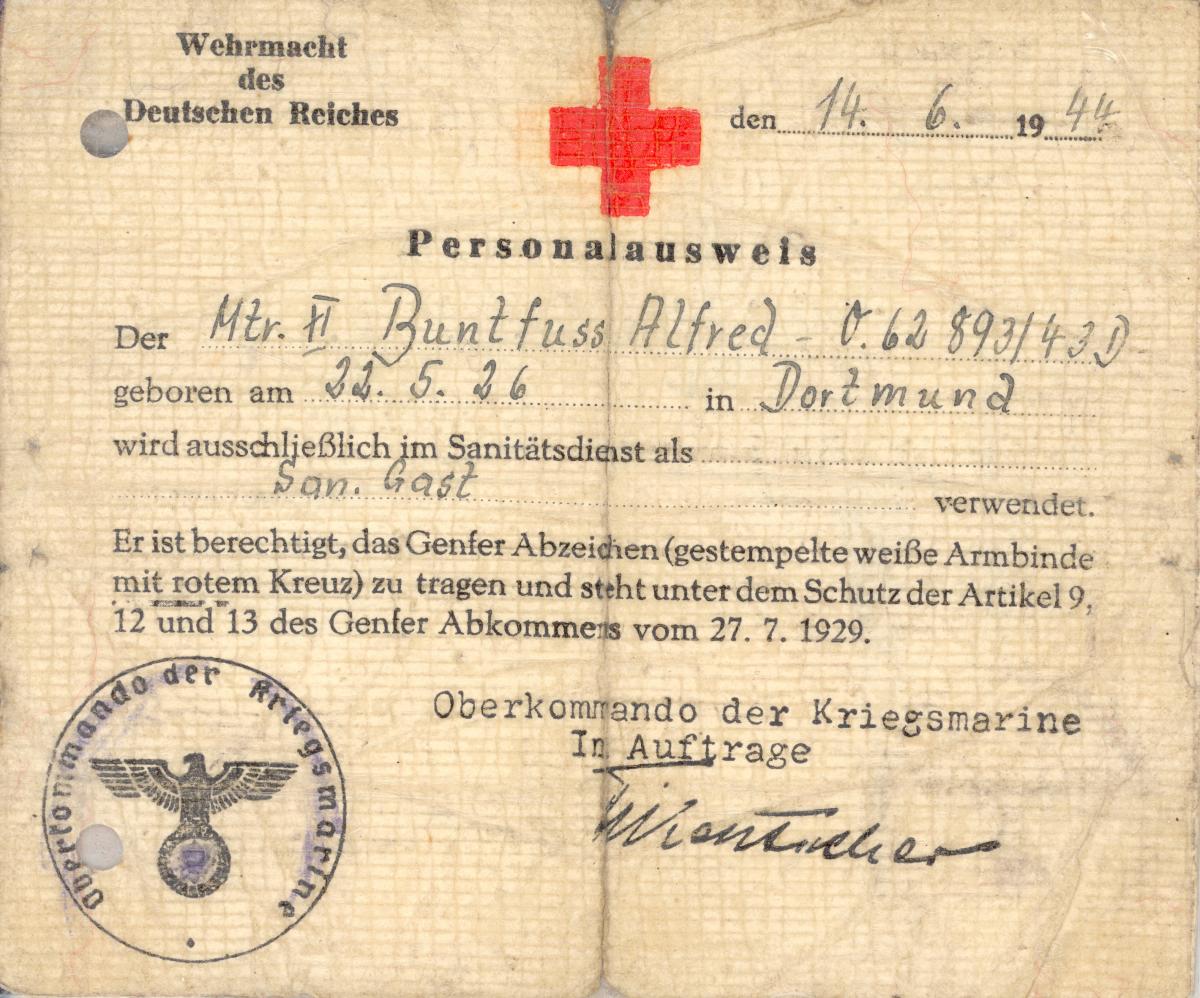

After the Reichsarbeitsdienst, I went home but there was a letter on the table saying that I would be drafted in just three days. I actually wanted to pass my exam as a barber while at home, but there was not enough time. I was inducted and served in the navy. The basic training was in France, in the Vosges Mountains. I was to be a medic. After one month in France, I was transferred to a convent in the Netherlands. There were still monks living there, and we received training in every area—from surgery to how to treat the human body.

By June 1944, Alfred Buntfuss had completed his medical training and was now officially in the navy. He served aboard various ships in the North Sea and docked on several occasions in German-occupied Norway. Once he arrived late and missed the transfer to another ship. Using a few days of wait time, he managed to visit his father, who was stationed a few hours from the port. As Alfred later explained, “It was a remarkable experience for me and my father during those two days because we had not seen each other for such a long time.”

Alfred Buntfuss was a certified medic (A. Buntfuss)

Alfred Buntfuss was a certified medic (A. Buntfuss)

As a navy man, Alfred was never in mortal danger, but he learned the importance of listening to the voice of inspiration. As he later explained,

Once, we had a four-hour break, and I heard a voice telling me that I should not undress. I did not know how to respond, and the voice came again. Seconds later, the ship went over a mine, but we were lucky because it only affected one side. We stopped at the next harbor right away. They fixed the holes, and we went on. Two days later, the same thing happened to us. I had listened to the voice telling me to stay in my clothes. That night, when [our ship] sank, I was the only one not in my sleeping gear.

Käthe Braun finished her occupational training in 1943, but instead of seeking employment, she was assigned by the government to work at a munitions factory in Christianstadt in western Silesia, hundreds of miles to the southwest. Her job was to monitor the readings on large boilers, and she worked twelve-hour shifts. With weekends free, she attended Church meetings in branches in Breslau and Liegnitz. Käthe remained at that location until the war ended.

In general, the citizens of Insterburg were relatively safe during the war because Germany’s enemies—the Allied air forces—were too far away to attack the city from the air. All of that changed in the fall of 1944, when the government suggested that evacuating Insterburg would be wise. Gertrud Buntfuss had to flee the city without the assistance of her husband or her son. She left her home shortly before Alfred returned on leave in October 1944 and was fortunate to make her way safely to the province of Mecklenburg (north of Berlin).

“We left with about a week to spare,” Ruth Braun explained. She and her mother made the trek of one hundred miles to the west and south to the town of Preussisch Holland, at the very western border of East Prussia. They were there when the Soviets came through the region in early 1945.

In January 1945, Ruth Braun made her way to the Insterburg railroad station with lots of clothing and a small supply of food. She managed to get aboard a train overloaded with desperate refugees trying to reach Königsberg. Ruth planned to travel west with several other relatives. She said good-bye to her father at the station because he had been inducted into the Volkssturm and was required to stay and defend the city.

Ruth’s party made it to the Baltic Sea coast at the port town of Pillau. During the harrowing trip, when it often seemed like they would not find passage across the Baltic, Ruth constantly prayed for deliverance. It was freezing cold, and food was scarce. The threat of being caught by the invading Soviets prevented any feeling of safety or security. Finally, they were taken aboard the ship Tatti and found themselves sailing westward.

After a voyage of about three hundred miles, the ship docked at Warnemünde. The passengers were safe from the invaders for a time. From there, they rode the train west to the town of Elmshorn, north of Hamburg in the province of Schleswig-Holstein. In Elmshorn, Ruth watched as British troops drove through the streets in May 1945; there was no fighting. For Ruth Braun, the war was finally over. Soon a branch of the Church was established in Elmshorn for Saints who had been forced from their homes in the provinces of eastern Germany.

At work in the factory in Silesia since 1943, Käthe met a man named Willi Leupold, a fellow employee. He was fifteen years older but very polite and nice to her. In a few months, they became close friends, and by April 1945 they were married. She had by then lost all contact with her family in Insterburg. The Red Army was closing in on the factory, but she had Willi to protect her. They began walking west, hoping to reach the area where the American army was known to be. However, the invaders overtook them, passing them on the road in their rush toward Berlin. In the confusion, Käthe and Willi reversed their travel and headed east, thereby passing the Soviets on the way. As moving targets, they avoided becoming civilian casualties.

Shortly after the war ended in May 1945, Polish soldiers arrived in Reichenau, where Käthe and Willi were living, and informed the German populace that they were being expelled from the country; Poland had been given that territory, and the new owners wanted the Germans out. The process was painful, as Käthe later wrote:

Like cattle we were driven to a pasture. Old and young were thrown out of their homeland where generations of their ancestors had lived. What a tragic scene greeted our eyes. Old and sick people who could not walk were loaded into small handcarts. Grandfathers and grandmothers pulled or pushed the carts as we were organized into travel companies. Everywhere there were guards with bayonets. All of us were shocked at their brutality and could hardly understand what was happening. Thus began the great exodus.

When they reached the new German border, the Polish police told the refugees, “Don’t come back!” Käthe and Willi Leupold then found a place to live just inside the Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany. In early 1946, Käthe learned that a branch of the Church was holding meetings in nearby Görlitz, and she joined them for a conference. After three years of sporadic attendance, she had a solid connection with her church again.

According to Käthe Braun Leupold, her mother was never able to leave Preussisch Holland. Under the poor living conditions of the time, she contracted polio and died there in August 1945. Wilhelm Braun survived the Soviet conquest of Insterburg and found his way to western Germany in 1946, where he was united with his daughter, Ruth. His son, Walter, had been taken to Russia as a forced laborer. Although his health was substantially weakened, Walter survived and returned to Germany in 1947.

After the war, Alfred Buntfuss was in a POW camp and happened to visit the office of a dentist who recognized his name. The man had recently treated Alfred’s father, Emil, and allowed Alfred to use a radio to send a message regarding his father. Eight hours later, a response arrived indicating his father’s whereabouts. They could not yet meet, but were allowed to talk on the telephone several times.

Alfred Buntfuss was a POW in the British Occupation Zone with duties that included clearing the North Sea of mines. Eventually he filled out a missing persons card on his father (at the latter’s last known location), and to his surprise, Emil showed up one day at the camp gate. The missing persons card had functioned to perfection.

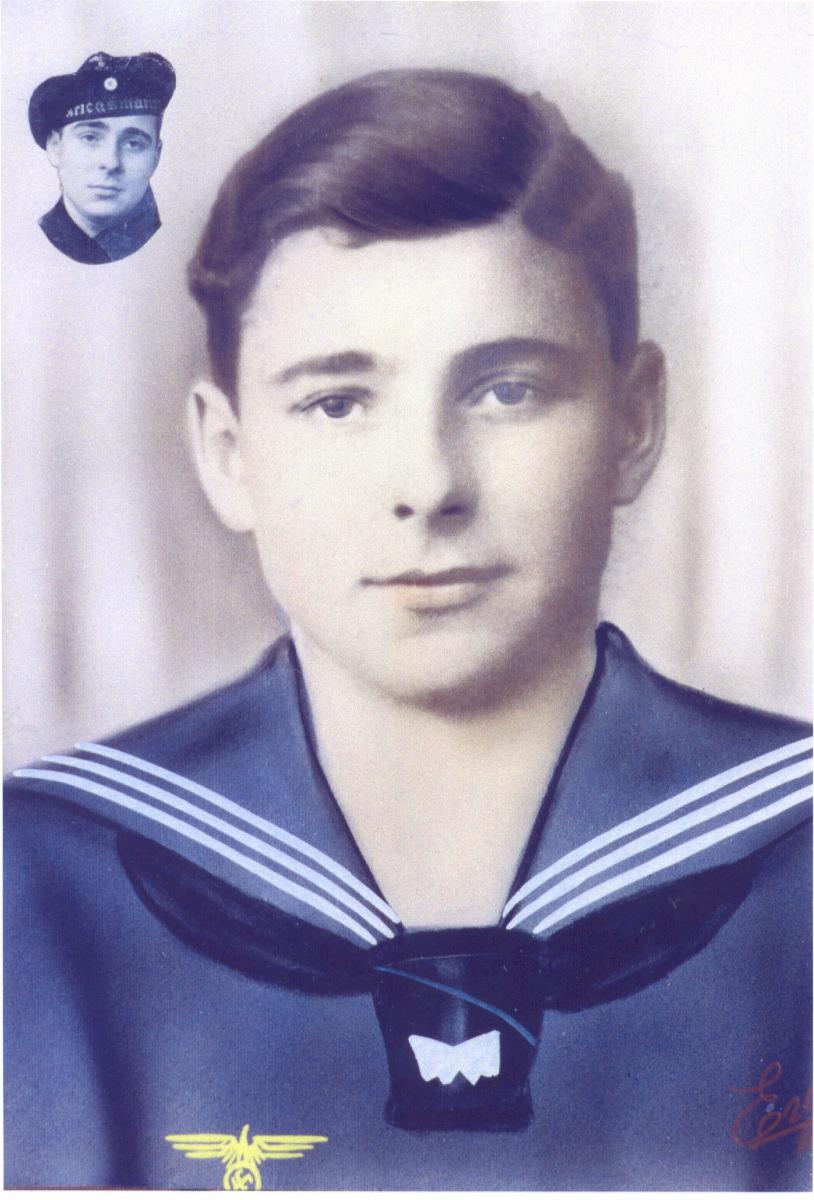

Alfred Buntfuss as a sailor in the German navy (A. Buntfuss)

Alfred Buntfuss as a sailor in the German navy (A. Buntfuss)

In 1946, Alfred and his father were both free and traveled to Mecklenburg to find Minna Buntfuss for a joyous reunion. According to Alfred, “It was such a great blessing for all of us.” They were in the Soviet Occupation Zone and starvation was a way of life, but at least they were alive and together. The war was finally over for the Buntfuss family.

There were no Germans left in Insterburg by the fall of 1946. The small branch there had ceased to exist.

In Memoriam

The following member of the Insterburg Branch did not survive World War II:

Henrietta Amalie Braek b. Klein Genie, Gerdauen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 20 or 26 Aug 1869; dau. of August Braek and Amalie Lagnuke; bp. 23 or 29 Apr 1931; m. Adolf Hoffmann; 1 child; d. in flight 1944 or 1945 (IGI)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Käthe Braun Luskin, autobiography (unpublished); private collection.

[3] Albert Buntfuss, interview by the author in German, Leest, Germany, August 31, 2006; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] Ruth Braun Fricke, interview by the author in German, Hamburg, Germany, August 15, 2006.

[5] Alfred Bork, diary(unpublished), April 5, 1942; private collection; trans. the author

[6] Ibid., April 12, 1942. Alfred wrote on June 6, 1942, that “Brother Repkowski” of Königsberg, whose family he visited that day in Königsberg, was the leader of the Insterburg Branch.

[7] East German Mission, “Directory of Meeting Places,” (unpublished, 1943); private collection.