Hohenstein Branch, Chemnitz District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 193-8.

The town of Hohenstein is nine miles directly west of Chemnitz in what is called the Ernstthal Valley in Saxony. With sixty-nine members in 1939, this was the third largest branch in the district, serving members living in Hohenstein itself and in several surrounding villages.

| Hohenstein Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 2 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 2 |

| Deacons | 4 |

| Other Adult Males | 16 |

| Adult Females | 40 |

| Male Children | 0 |

| Female Children | 4 |

| Total | 69 |

The Hohenstein Branch met in rooms in the first Hinterhaus at Logenstrasse 16. “We entered through two gates and then came into the courtyard where the building was,” recalled Ilse Böhme (born 1925).[2] It was a manufacturing building, and the meeting rooms were on the main floor. The members did their best to make the rooms more compatible for worship services, according to this entry from the East German Mission history:

Monday 5 Dec 1938: From this day on until December 17th, the Hohenstein Branch, Chemnitz District, was completely renovated and remodeled. All members took active part.[3]

This kind of renovation campaign was very common among Latter-day Saint branches in Germany.

Ilse Böhme and Eva Göckeritz (born 1934) both remembered an embroidery with the words “The Glory of God Is Intelligence” hanging from the pulpit that stood to the side of the chapel. The rostrum might have been one step up from the main floor. “We had some interesting classrooms,” explained Eva, “The children all went together in the room where we had to walk around a factory boiler.” Class was sometimes held in the courtyard as well. Attendance on Sunday may have been thirty to forty persons.[4] The MIA met on Tuesday evenings and the Relief Society on Thursday evenings.

Ilse Böhme recalled that the rooms were warm if there was sufficient coal, but as the war progressed, there was no coal to be found and the members had to wear their coats to stay warm.

Shortly before the war, Ilse became acquainted with the poor condition of Jews in Nazi Germany. Near the church was a camp full of Jews, as she recalled:

I saw them being hurt and beaten. That was horrible. One time I said to a man from the SS, “If you raise your hand one more time to hurt these poor people, you will have me to answer to.” He replied, “If you were not so young, I would report you right away, and you would be heading for a concentration camp.”

Although expected to do so, Ilse Böhme did not join the Bund Deutscher Mädchen when she turned fourteen. As she later explained, “I received threatening letters indicating that the police would come for me if I did not attend. But I responded that Sunday School was enough for me. I was the only girl in my class at school who did not go.”

Georg Göckeritz, the president of the Hohenstein Branch, lived seven miles south of the city in a small town called Neuwürschnitz. Brother Göckeritz had moved there from Chemnitz to work as an accountant in the town’s only factory and built a house for his family there. According to his daughter, Eva, it was quite a trip to church: “We had to walk for one hour, then we rode the trolley for forty-five minutes, then we walked another fifteen to twenty minutes. We left home at 6:00 or 6:30 a.m.” The Neuwürschnitz neighbors called Georg Göckeritz “the running Mormon preacher” because he was always in a hurry to get to church and walked well ahead of his family.

The only time the Göckeritz family went to church during the week was for MIA, “because my dad was the teacher,” recalled Eva Göckeritz. “MIA was a branch activity and everybody came.” Primary was held during the week without the Göckeritz children, who had Primary meetings with their mother in Neuwürschnitz. Hildegard Göckeritz invited neighborhood children to join them, and the gatherings were quite popular.

Rose Göckeritz (born 1939) recalled how her father, who had lost an eye at age sixteen, was drafted into the German army several times. As an accountant at a local factory, he was indispensable to his employer, a Herr Friedrich. Georg Göckeritz must have felt himself immune from military service because each time he was drafted, Herr Friedrich managed to have the call deferred. However, the employer’s good graces had their limits, because Brother Göckeritz refused to join the Nazi Party and dared to argue with his employer on the topic of politics versus religion. One day he insisted that “I believe in God, and I believe in Jesus, and Hitler does not figure in what I believe.”[5] For Herr Friedrich, that was the straw that broke the camel’s back, and he made no attempt to protect his employee when the next draft notice came. Despite having only one eye, Georg Göckeritz was needed by the Reich. Fortunately, his handicap prevented him from receiving a combat assignment. He was sent to Lüneburg in northern Germany and was never in danger.

The branch in Hohenstein/

The branch in Hohenstein/

In March 1941, Georg Göckeritz came home on furlough. His wife recorded her thoughts about the event in her diary:

March 9, 1941: We have had such a fine time together. We all went for a walk this afternoon. Raimund constantly holds on to his Papa. Soon he will leave us again. I walked with him as far as the Luther beech tree and the moon was shining! It was harder than I thought it would be. But it must be this way. One last kiss, then we went our separate ways. May God grant that we may be reunited again soon.[6]

Eva Göckeritz turned eight in 1942 and was baptized in Chemnitz in the back yard of the Emil Heidler family home. The baptismal font was the concrete basin used by the family to catch rainwater. As she later reported, “I was baptized in that waterhole in the pitch dark. Most of the baptisms were done in secret. . . . My own mother wasn’t there.” Later on, baptisms were performed in an indoor swimming pool in Hohenstein. Eva Grossmann’s father, Ernst (not a member of the Church), was an employee there and allowed the Saints to come in after hours for baptismal ceremonies.

According to the East German Mission record, the Hohenstein/

As Eva Grossmann recalled, there were several military industries in Hohenstein that attracted the attention of Allied bombers. On one occasion, an American or British airplane was shot down and crashed just down the street from the Grossmann home. On two other occasions, dive-bombers chased her and shot at her. Some of the Allied tactics were truly disturbing, she recalled, such as when the planes dropped “little dolls and pencils and stuff” that were actually trick incendiary devices. “When you touched the things, they would explode. A lot of children got killed or lost some of their [fingers].”[8]

There were not very many fun things to do in wartime, as Raimund Göckeritz (born 1937) recalled.[9] Some activities such as soccer games took place on Sundays, but Raimund was not allowed to participate in them. His best friend lived just two houses away, but the alarms of potential air raids were a constant concern. Despite the terrible reality of it all, some aspects of war were fascinating, as he later explained:

I still remember one time when a dogfight [took place] right in front of our house, and we watched [the pilots] shoot at each other. It was about three airplanes chasing one airplane. One got shot down. . . . We saw it from our house. It landed somewhere in the field.

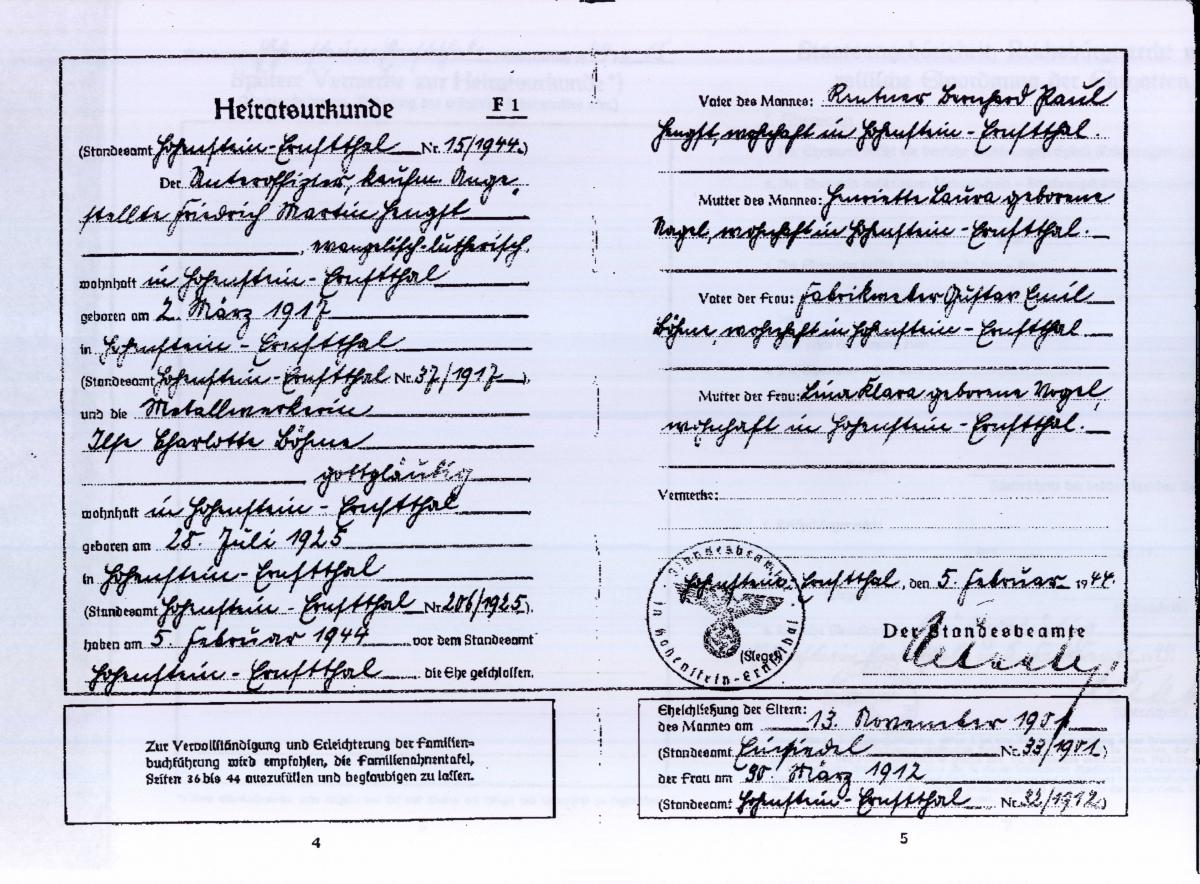

The marriage certificate of Ilse Böhme and Friedrich Martin Hengst dated February 5, 1944. She is described as gottgläubig (“God-believing”). (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

The marriage certificate of Ilse Böhme and Friedrich Martin Hengst dated February 5, 1944. She is described as gottgläubig (“God-believing”). (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

Ilse Böhme was married in the civil registry of the town hall on February 2, 1944. She was a bit young at the time but was certain that she would be ordered to work for the army if she did not marry soon. Her groom was Martin Friedrich Hengst, and they had only three days before he had to return to his post. About a year later, he was captured by the Americans, and Ilse had no idea of his whereabouts for quite a while.

Georg Göckeritz eventually served three different stints in the German army. He left home for the third time on December 8, 1944. Little Rose Göckeritz (born 1940) clearly remembered that sad farewell. Again, Georg’s wife, Hildegard, confided her feelings to her diary:

It was hard to say good-bye, but with the Lord’s help we will survive this. His last words were directed to his children. He is our most precious possession next to the gospel. . . . We all want to hold onto each other tightly, so that we can get through the worst. All year long, we have been able to go to Hohenstein to church and that has really been nice. May we be blessed to continue to do so.[10]

In early 1945, several million Germans left their homes in the eastern provinces and fled to the west. Some of them came through Hohenstein seeking a place to live. The Grossmann family took in about a dozen relatives. As Eva reported later, “We had only three big rooms and a little kitchen. It was pretty messy!”

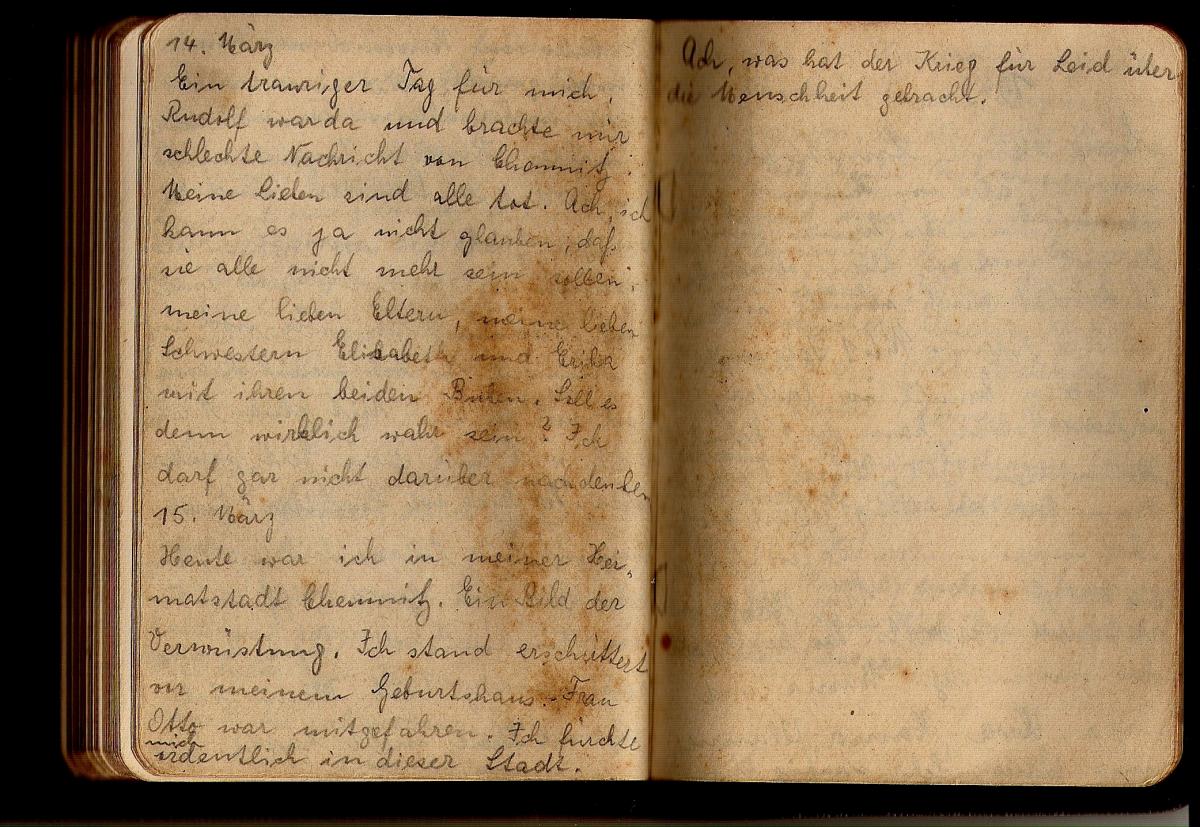

On March 14, 1945, Hildegard Fischer Göckeritz wrote in her diary about the death of her parents, two sisters and two nephews in nearby Chemnitz. (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

On March 14, 1945, Hildegard Fischer Göckeritz wrote in her diary about the death of her parents, two sisters and two nephews in nearby Chemnitz. (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

Raimund Göckeritz’s parents consistently prayed that the war would end soon, and they told their children that they believed that Germany could not win the war. Young Raimund repeated some of their statements in school, which could have caused serious problems had his teacher been a fanatic Nazi. Fortunately, he was not and took the time to caution the Göckeritz parents about what they said in the presence of their children.

In February 1945, a district conference was held in Chemnitz, and Ilse Böhme Hengst recalled the conclusion of the conference vividly:

President Langheinrich [of the mission leadership] was there. At the end we sang “God Be with You till We Meet Again,” and we all held hands. We had never done that before. Two weeks later they [many members in Chemnitz] were all dead.

Two weeks after the conference, on March 5, 1945, the city of Chemnitz suffered a catastrophic air raid. Late that night, Hildegard Göckeritz and her daughters emerged from the basement of their Neuwürschnitz house and saw the red sky over Chemnitz, twelve miles to the northeast. Sister Göckeritz’s parents, Bruno and Johanna Fischer, were members of the Church living in Chemnitz. Eva, then ten years old, later described her mother’s reaction to what she imagined was going on in her hometown:

I will never forget the look on my mother’s face. I think she knew [what happened to her parents] because her face was bright red. . . . The next morning there were all these people coming [from Chemnitz] with their hair singed and their eyebrows, dragging little kids, and some of them had lost their shoes and clothes. It was really sad. And we were just hoping that our family would come too, but they didn’t.

Day after day, no word came from Chemitz regarding the status of the Fischers. On March 10, 1945, Hildegard Göckeritz wrote of her concerns in her diary: “I still have no word from Chemnitz since the terrible attack on March 5. . . . If I didn’t have the Church right now . . .”[11]

What she had feared the most became a reality on March 14:

A sad day for me. Rudolf was here and brought the bad news from Chemnitz. My loved ones are all dead. Oh, I just can’t believe that they’re all gone. My dear parents, my dear sisters Elisabeth and Erika, and her two little boys. Can it really be true? I dare not even think about it.[12]

She hurried to Chemnitz to see for herself and made this entry the next day:

Today I was in my hometown, Chemnitz. The picture of destruction. I stood devastated before the house in which I was born. Mrs. Otto went with me. I am really scared to even be in this city. Oh, what terrible suffering this war has brought upon mankind.[13]

In what may be the single worst tragedy in the Church in Germany in World War II, eight Saints had perished in the Fischer home in Chemnitz on March 5—six members of the Fischer family and two elderly sisters who had sought refuge in the Fischers’ basement when the alarms sounded. Apparently, a direct hit had killed them all instantly.[14]

A few days later, Herbert Heidler, a deacon in Chemnitz, rode his bicycle all the way to Neuwürschnitz. He told the family that he had personally seen the bodies of the Fischers, and he brought them some of their personal effects, including two purses. Eva later recalled:

The smell of the things was so terrible that we couldn’t even bring them into the house. . . . First my mom put them on the back step, then the smell was so bad that we put them into a little greenhouse. When they finally aired out a bit, we brought them in. I don’t know if we even kept them.

Georg Göckeritz was granted a furlough of two weeks to console his wife over her loss. Some neighbors tried to convince him to stay home—to not return to his unit—because the war was lost anyway, they said. He resisted the temptation to desert, knowing that it could cost him his life if he were caught; he dutifully returned to his unit in northern Germany.

The town of Hohenstein was spared great damage during the war, but there was at least one frightening occasion for Ilse Böhme Hengst. In April 1945, “one last bomb was dropped next to our house. It left a hole big enough to build a new house in. I was thrown against the stove but I wasn’t hurt.”

Eva Grossmann’s mother very nearly suffered the fate of a defeatist. One day in late April 1945, she went to the city hall to get money from her husband. She told a girl there that she needed to buy groceries soon because the American army was approaching the town. The girl reported her to the police, and Eva’s mother was arrested. Eva (then thirteen years old) went along and was so upset by her mother’s situation that the police chief scolded her sharply: “What are you crying about? Your mother is still alive, but she should be shot! You’ll hear from us!” Fortunately, the Americans were indeed very close by. They entered the city and arrested the police chief before any action could be taken against Sister Grossmann.

In Neuwürschnitz the war ended with the arrival of the American army. They shelled the village for a while, and a few civilians were killed, but the Göckeritz home was not damaged. On the main street, somebody made a barricade of desks and chairs from the school in an attempt to stop the American tanks. Eva was the one to hang out a white sheet from their window to indicate that no resistance would be offered. “I remember that Hitler was still screaming over the radio, something about how we would still win the war.”

“It was frightening,” recalled Raimund Göckeritz. “We had never seen black people before, and most—I think about sixty percent—of the [American] soldiers were black, and they were big. . . . They went through all of our homes with their guns.”

The Americans searched the Göckeritz home but left with only one item: the Mother’s Cross that the government had awarded Hildegard Göckeritz for giving birth to six children for the Reich.

“My dad was captured by the British on my birthday, 29 April 1945. I will always remember that,” explained Eva Göckeritz:

They treated him like an animal, stole all of his valuables, etc. Then he was assigned to work in an office and he had a decent life. He had to write the orders for people to get released. One day the colonel said, “Why don’t you write your own release order?” and so he did.

Eva and Raimund Göckeritz both recalled coming home from church one Sunday in the summer or fall of 1946 to find their father sitting in the kitchen. According to Raimund, the reunion was “heaven on earth; it was unbelievable.” The young Göckeritz family had survived the war, and their home was intact.

Eva Grossmann’s father, Ernst, was in Czechoslovakia when the war ended. He avoided capture and sneaked across the border into Germany, just a few miles from Hohenstein. When he arrived at his home just weeks after Germany’s surrender, he was in excellent health. Eva’s brother, Ernst Robert, was captured by the Soviets and did not return from the Soviet Union until 1949. She recalled seeing him approach the house on the final leg of his journey: “He came down the street really slowly, and he had no shoes on, just old rags. He looked horrible, but he was alive.” Regarding the Hohenstein Branch during the war, Eva Grossman stated that “we kept very close and had good times.” Her own family was richly blessed, in that no close relatives died.

Looking back on her war experience, Ilse Böhme Hengst later stated, “I had a testimony of the gospel. . . . We did not mourn concerning the war and our relationship to our Heavenly Father. We did not doubt that our Heavenly Father loved us.”

In Memoriam

Only one member of the Hohenstein Branch did not survive World War II:

Friederike Wilhelmine—b. 30 Jan 1861; bp. 18 Jul 1925; m.—Gäbler; 1 child; d. Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Chemnitz, Sachsen 2 Mar 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, No. 15, 13 Apr 1941, 60)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Ilse Böhme Hengst, interview by the author in German, Hohenstein/

[3] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 50, East German Mission History.

[4] Eva Goeckeritz McClellan, interview by the author, Payson, Utah, April 3, 2007.

[5] Rose Goeckeritz Groebs, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, January 19, 2007.

[6] Hildegard Fischer Göckeritz, diary, March 9, 1941; private collection; trans. the author.

[7] East German Mission, “Directory of Meeting Places” (unpublished manuscript, January 31, 1943); private collection.

[8] Eva Maria Grossmann Donner, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, February 2, 2007. In the last few months of the war, the Allies enjoyed total air superiority over Germany.

[9] Raimund Goeckeritz, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, March 3, 2006.

[10] Göckeritz, diary, dated December 8, 1944.

[11] Ibid., dated March 10, 1945.

[12] Ibid., dated March 14, 1945.

[13] Ibid., dated March 15, 1945. This was the last entry made before 1949.

[14] See the Chemnitz Center Branch chapter for full details on the fate of the Fischer family. It is possible that more members of the Church perished in a single night in Hamburg in July 1943, but no details are available.