Guben Branch, Spreewald District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 440-5.

The city of Guben is situated on the Neisse River in the southwest region of the historic province of Brandenburg. During the decades before World War II, the city had expanded to the east across the river. Approximately 40,000 people lived in Guben in 1939.[1]

| Guben Branch[2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 4 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 1 |

| Deacons | 7 |

| Other Adult Males | 7 |

| Adult Females | 22 |

| Male Children | 4 |

| Female Children | 3 |

| Total | 49 |

An interesting notice is found in the history of the East German Mission on February 28, 1938: “In Dresden and Guben the elders, without any specific reasons, were asked to leave these cities within a specified time. At the intervention of [mission president] Alfred C. Rees, the elders were not banished, and they were told to remain until further notice.”[3] It is not known why the missionaries were asked to leave or in what office the mission president petitioned to have the order rescinded.

For reasons unknown, the morale of the Guben Branch must have been a bit low in late 1938. However, the following entry in the mission history lent hope to the situation:

Sunday, November 27: President and Sister Rees attended a special meeting in the Guben Branch, where they spoke and brought “new enthusiasm and cheer into the hearts of the attending members and friends.”[4]

In September 1938, the acting branch president in Guben was Otto Sasse, with Walter Czerny and Helmut Kleeman serving as acting counselors.[5] Eyewitnesses identified Willi König as the branch president several years later. The branch met in rented rooms at Lindengraben 13. Helmut Schulz (born 1932) recalled that the street was on the east side of the river, very near the bridge over the Neisse. He described the meeting rooms as follows:

First you came into a corridor, a small room, a cloakroom. We even had a class in there too after the Sunday School split. You came into a bigger room like a big living room, and there was even a little stage in there too; there was a curtain there, and it was in the regular [apartment] house where people lived. There was not an extra building around it, nothing like that.[6]

Sunday School was held at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting in the afternoon. Other meetings were held on evenings during the week, according to Walter Luskin (born 1922).[7]

Helmut Schulz’s father was drafted right away when the war started. He saw action in the Polish and French campaigns and then was transferred to Russia. It was there that he was severely wounded in the right shoulder by an artillery round. It took him a full year to heal, but fortunately he was sent to a hospital in Guben where he could be visited by his family. By 1943, he was back in France but no longer able to carry a rifle.

Because his father was away from home for long periods of time, Helmut was not baptized in 1940 but had to wait until he was nine. Walter Czerny, home on leave, conducted the ceremony. After he left, the only priesthood holder in Church meetings was young Walter Luskin, a teacher in the Aaronic Priesthood. A priest or elder from another branch in the district came each week to conduct the meetings and to administer the sacrament to the members in Guben. As Walter recalled, “I was asked by Brother Ranglack [first counselor in the mission leadership] to lead the meetings until the branch president came back.”[8]

Members of the Guben Sunday School posed for this picture in 1934. (P. Czerny)

Members of the Guben Sunday School posed for this picture in 1934. (P. Czerny)

Walter Luskin’s father was born to Jewish parents but married a Lutheran girl. During the Third Reich, his ancestry provided reason for local persecution and could have led to his incarceration. However, the Luskin family’s neighbors were Latter-day Saints, and they prayed for a peaceful resolution to the problem. Soon afterward, Herr Luskin passed away. Walter, one-half Jewish by blood, was thus spared military service. He was baptized into the Church with his mother on June 13, 19 42. Walter’s status in the eyes of the government changed dramatically after the death of his father, as he explained in these words:

From this time on we were a little bit more free. For me it was the greatest blessing that could happen because they did not take me into the German army. They asked me if I would go as a volunteer and I didn’t do this. They didn’t draft me into the army. They drafted me to work for the army. I was a tailor. I worked in the army, in the army tailor shop [in Guben] until the end of the war.

Young Helmut Schulz was forced to make a personal sacrifice for the war effort in early 1943. The sled he had received for Christmas was confiscated just a few weeks later by the German army for military use. Helmut cried and ran after the soldiers, but they did not return his sled.[9] Nearly eleven years old, Helmut was already a member of the Jungvolk but was not prepared to sacrifice everything for his country.

Helmut’s father was captured by the Allies after the invasion in Normandy, France, in 1944. Via Africa, he was shipped to the United States where he spent his time in a POW camp until the summer of 1945. A postcard from the Red Cross informed Sister Schulz of her husband’s status.

Records of the East German Mission indicate that the meeting place of the Guben Branch had moved by 1943 to Crossenermauer 13a. Walter Luskin indicated that the street was in the older section of Guben on the west side of the river. “When we left home [in 1945] I did see the meetinghouse in flames, burning.”

Young Peter Czerny (born 1941) recalled participating in the ordinance of the sacrament in the last days before evacuating Guben:

The [meeting] rooms were all intact because the war hadn’t arrived yet. There was one row of smaller chairs up front for little children. This was one of the first times I was allowed to sit up there. As they passed the sacrament, I noticed that there was one piece of bread that was extra large, so I thought, “Oh, wow, I’ll get this before anyone else.” I reached way over trying to get it and knocked the tray out of the young man’s hand. It was very embarrassing. But [because of that experience] I know that we had at least the Aaronic priesthood in the branch.[10]

The city of Guben was not a crucial industrial town so it was not the target of numerous air raids. Helmut Schulz could remember only one (as well as constant blackouts), but he recalled that the town was extensively damaged when the invaders arrived in early 1945. German defenders held the Soviets at bay for a while but ultimately gave way. Walter Luskin reported that the Red Army shelled the city for six weeks and tried several times to conquer it. At one point, Sister König, the wife of the (absent) branch president, asked Walter and his mother to come to her apartment on the east side of the river. They complied, and that night the bombardment became so fierce that they could not return home. For the next eleven days, they lived in the basement of the König family’s apartment house. Then the German defenders instructed them to leave because a counterattack was expected at any time.

The Guben Branch Christmas party of 1936 featured a visit by Sankt Nikolaus. (P. Czerny)

The Guben Branch Christmas party of 1936 featured a visit by Sankt Nikolaus. (P. Czerny)

As the threat of a Soviet invasion intensified, a young mother in the branch, Sister Iseke, came to Walter. She appealed to him for advice, in that he was the only priesthood holder of the branch who was still at home. Should she take the train and flee Guben with her three little boys? He said that she should, but if there were no room on that train, she was not to take the next train twenty minutes later, but to stay in Guben. She did indeed miss the first train and stayed home. Later they learned that the second train had been destroyed in the Cottbus railroad station during an air raid.

Walter Luskin and his mother fled Guben with several other branch members, stopping first in Sedlitz, then in Vetschau—both small towns a few miles to the west. From there they were able to visit the branch in Cottbus on several Sundays. Eventually, the Soviets arrived and forced them to leave. They headed back toward Guben but were fortunate that their path took them to Cottbus. There they decided to stay in the building that Fritz Lehnig had acquired and converted into a refugee home.[11]

Helmut Schulz, his mother, and his baby brother fled Guben with other members of the branch. They first tried to reach Berlin, but Red Army soldiers prevented that and instructed them to return to Guben. At first, Polish soldiers did not allow them to cross the Neisse River to their neighborhood on the east side, but the three wanted very much to see their home and to learn the fate of other members of the branch. They constructed a makeshift American flag and by using it talked their way across the pontoon bridge that the invaders had erected. The Schulz home had been totally destroyed, but the homes of other members were still standing. The Polish soldiers did not allow them to stay, so they made their way to Cottbus, about fifteen miles to the southwest.

On the train headed for Cottbus, the Schulzes were subjected to an unexplained delay. The train halted in the country for two hours, and nobody understood why they weren’t moving. When they finally proceeded and arrived in Cottbus, they learned that a major air raid had struck the city while the train waited in the country. Many people were killed when the railroad station was bombed. Helmut was convinced that his Heavenly Father had saved them by delaying the train’s arrival in Cottbus.

Peter Czerny later quoted the handbill posted around Guben that announced the departure of women and children from the town: “The way the Germans wrote was interesting; they said it would be a well-disciplined evacuation (Wir wollen die Evakuierung in Ruhe und Besonnenheit vollziehen.), but we were all running for our lives.”[12]

Helene Czerny (whose husband was on the Eastern Front at the time) took her two young boys and moved westward. They were first assigned to live with farm families in the little community of Stradow, west of Cottbus. From there, they hoped to make it west far enough to see the Americans as conquerors. The conquerors had different ideas and prevented any westward migration. They actually tried to stop refugees from moving eastward as well, which meant that Sister Czerny could not take her family to Cottbus to join the Saints there. Fortunately, when she and other women and children approached the guard station on the road to Cottbus, the guard was distracted by a cow that had not been milked in days. While he chased after the distraught animal, the women and children hurried past the checkpoint.

It was still February 1945 when the small group of Saints approached Cottbus. Fritz Lehnig met them on the road with several wagons, but they dared not travel at night, fearing attack by soldiers. One night they sought refuge in a small cemetery chapel. Peter Czerny recalled the tense overnight vigil:

We ran to a nearby cemetery and took refuge in the chapel there. . . . It was freezing outside, so they had just stacked up [dead] bodies and put some blankets over them. The adults kept it secret from us children so we wouldn’t be scared. I think if we had known, we would have gone nuts. There was no toilet inside the building, so we used empty flowerpots. . . . The majority of us were children. There were a few teenage boys and girls, and the rest were women.

The tension inside the cemetery chapel was almost unbearable for a child, but Fritz Lehnig instructed the children to be totally silent. In the vivid recollection of little Peter:

I wanted to cry. But in that same instant, a spirit came into my heart that made me feel so wonderful. It said to me, “Peter, everything is going to be all right. This is one time you don’t have to cry, even though you want to. Just go to sleep and it’ll be okay.” I immediately recognized it as my Father in Heaven, helping me not to cry. I know that same spirit was touching all the little babies and children in the group, but I was the only one old enough to remember what happened. None of us could cry.

Most of the LDS women made it to the cemetery chapel, but a few were raped because they could not make it out of the previous house in time. One teenage LDS girl was assaulted by at least eight men. Several other women suffered the same tribulation before they could reach the Lehnig home in Cottbus.

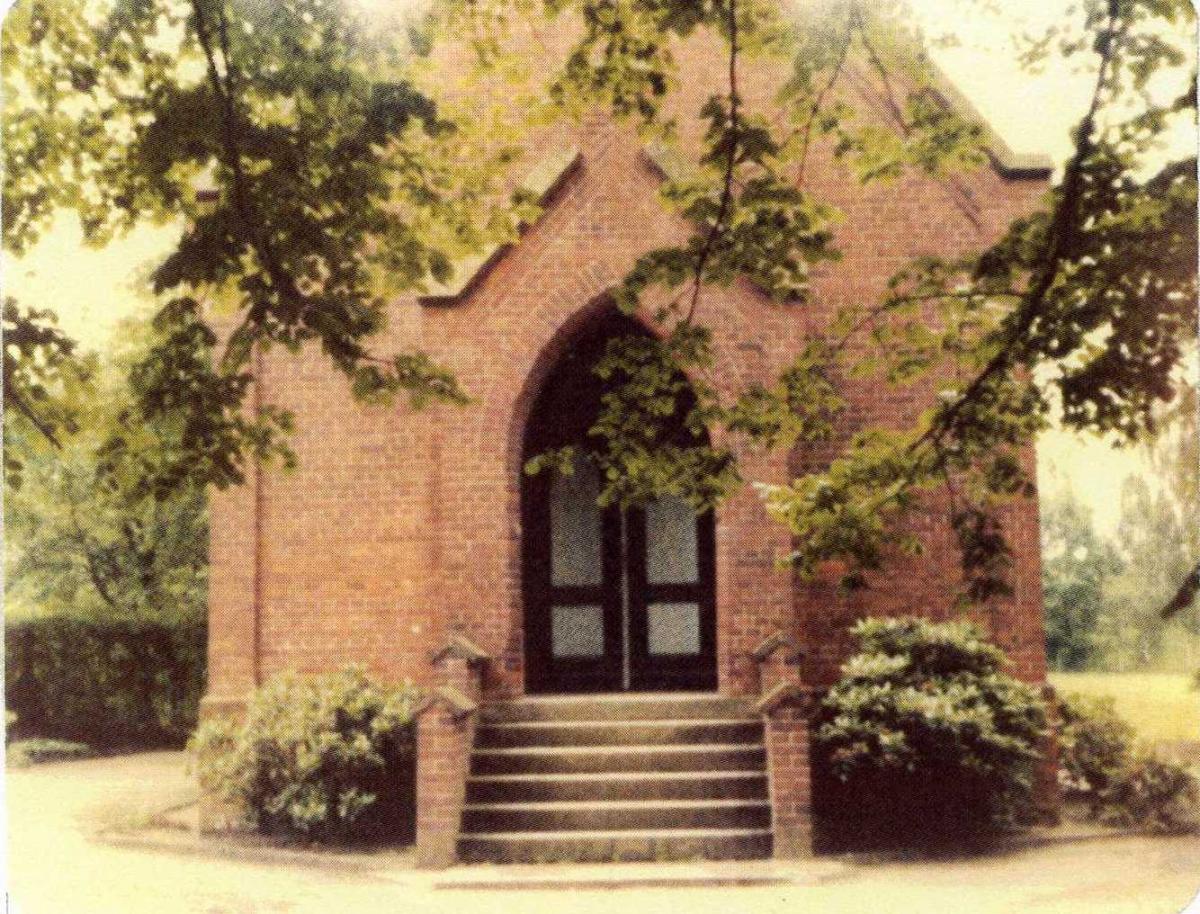

The cemetery chapel where the LDS refugees sought safety one cold night in February 1945 (E. Grünewald Schulz)

The cemetery chapel where the LDS refugees sought safety one cold night in February 1945 (E. Grünewald Schulz)

Sister Schulz and her two sons were also members of the large refugee colony at the Fritz Lehnig property in Cottbus in the summer of 1945. They had survived the war but would never return to their home in Guben. Helmut later stated: “I missed my hometown, yes, [but] in the [Lehnig] refugee camp, I had no time to think about it. I went back later and visited my aunt; she was still there. No friends, they were all gone. They were all killed.”

Life at the Lehnig property was remarkable in the recollection of Walter Lehnig. He later explained that as many as one hundred fifty persons lived there shortly after the war ended. Feeding them was such a challenge that the adults fasted twice each week in order to leave enough food for the children. Care was taken to hide the women every time a Soviet soldier approached the property, and the Saints were nearly always successful in this effort. Eventually, city officials came by and ordered that all persons not originally residing in Cottbus leave. From there, most of the refugees headed west to find a new place to live.[13]

When the adults went out into the countryside to forage for food, they often took children along and instructed them to sing and make merry when soldiers came by, to distract them from a possible search for contraband food in the wagons, according to Peter Czerny.

Apparently, no Latter-day Saints returned to live in Guben after the destruction of the city. The few who had not yet evacuated the city soon left. With their departure, the branch ceased to exist.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Guben Branch did not survive World War II:

Helmut Erhard Ewald Kleemann b. Hildesheim, Hannover, Preussen 2 Feb 1922; son of Karl Friedrich Richard Kleemann and Frieda Auguste Schmidt; ord. priest; m. Forst, Brandenburg, Preussen 3 Sep 1943, Martha Erna Anni Gäbler; 1 child; engineer; k. in battle Göppingen, Württemberg 16 Apr 1945; bur. Göppingen (E. Gäbler; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Karl Heinz Peter Rechenberg b. Guben, Brandenburg, Preussen 6 Oct 1924; son of Eitel Waldemar Ferdinand Julius Rechenberg and Leokadia Julia Scheibner; bp. 15 May 1936; ord.; k. in battle Tschitomir, Russia 11 or 18 Nov 1943 (W. Luskin; IGI)

Wolf-Dieter Eitel Rechenberg b. Guben, Brandenburg, Preussen 2 May 1923; son of Eitel Waldemar Ferdinand Julius Rechenberg and Leokadia Julia Scheibner; bp. 15 May 1936; ord.; corporal Waffen-SS; k. in battle Crespina, Pisa, Italy 10 Jul 1944; bur. Futa Pass, Italy (W. Luskin; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Notes

[1] The name of the city in the local Wendisch dialect is Gubin, the same spelling used in modern Poland.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[3] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 12, East German Mission History.

[4] Ibid., no. 47.

[5] Ibid., no. 39.

[6] Helmut Schulz, interview by the author, Sandy, Utah, July 26, 2007.

[7] Walter Luskin, interview by Rachel Gale, Salt Lake City, July 6, 2007; transcript or audio version of interview in author’s collection.

[8] Walter Luskin, “Lebensgeschichte von Walter Luskin” (unpublished personal history), 5; private collection.

[9] Helmut Schulz, “Helmut’s Life” (unpublished personal history), 72; private collection.

[10] Peter Czerny, interview by the author, Pleasant Grove, Utah, February 24, 2006.

[11] Luskin, “Lebensgeschichte,” 7.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid., 10.