Görlitz Branch, Dresden District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 258-68.

Seventy miles east of the city of Dresden, at the far eastern extent of the Dresden District, lies the city of Görlitz. In 1939, the town was situated on both sides of the Neisse River—the old part of town being on the west bank. The main railroad route from Dresden east to Breslau ran through Görlitz.

| Görlitz Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 2 |

| Priests | 3 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 7 |

| Other Adult Males | 18 |

| Adult Females | 62 |

| Male Children | 4 |

| Female Children | 5 |

| Total | 104 |

The Görlitz Branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints had 104 members at the time, making it the third largest branch in the Dresden District. Nearly two-thirds of the members were adult females.

Lifelong Görlitz resident Ruth Baier (born 1917) recalled the seating arrangement in the rooms in which the branch met during the war at Emmerichstrasse 68:

There always was one row with elderly sisters and then behind them sat the younger people and then came the youngest children. There were about 8–10 children and then 8–10 teenagers . . . there. This must have been about 35–40 people attending Sunday meetings.[2]

The branch observed the typical meeting schedule, beginning with Sunday School at 10:00 a.m. The members then went home for the noonday meal and returned in the evening for sacrament meeting. Relief Society, priesthood, and MIA gatherings were held on Wednesday evenings, with Primary meetings on Saturdays.

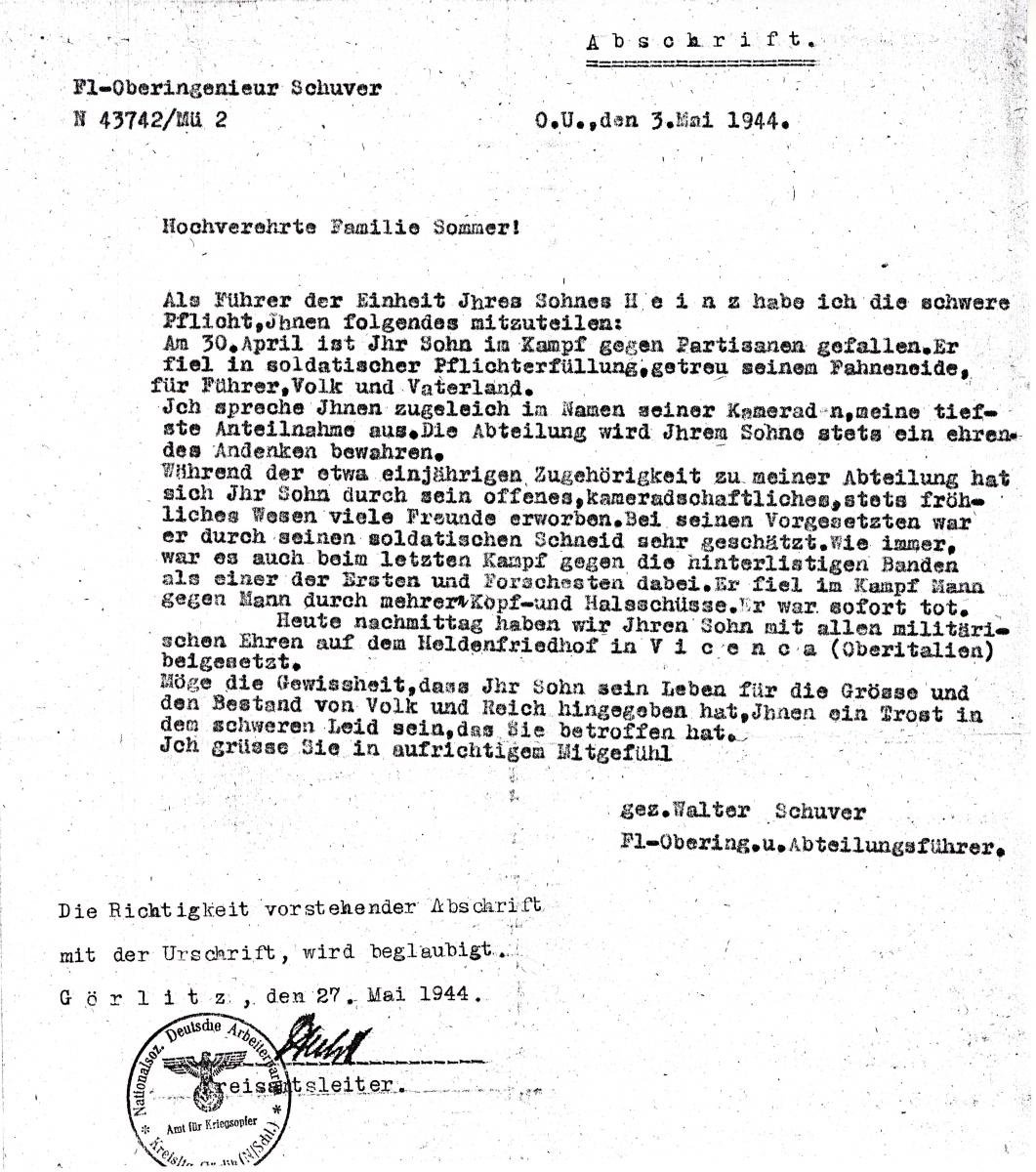

A celebration in the Görlitz Branch in 1938 (F. Larisch)

A celebration in the Görlitz Branch in 1938 (F. Larisch)

Helmut Habicht (born 1926) described the rooms in which the branch met:

We had a main room in the highest floor of a former factory building. We also had four classrooms. During the war, the owner also allowed us to use rooms on the main floor of the building.[3]

When World War II began, Anton Larish (born 1901) was the branch president in Görlitz. However, he had to be released when his employment with the Junker Aircraft Company required him to move in November 1939 to Halberstadt, northwest of Leipzig. His wife, Charlotte, and their children stayed in Görlitz. They would not be permanently united again until the last month of the war. In early 1940, Anton enjoyed two weeks at home. His diary entry for March 17, 1940, reads thus:

Everything went as hoped for and this is my first Sunday at home with Mutti [Mother] and children. . . . The reunion was a great day of joy for us all. I arrived in the night from Thursday to Friday at 12:30 a.m. Friday evening we had a family night with the children. Later I went with Lotte to a late-night performance at the theater.[4]

For Anton, the months in Halberstadt (180 miles northwest of Görlitz) became years, but the government did not allow him to move his family to Halberstadt. Every time a six-month period of employment came to an end, he looked forward to returning to Görlitz, but each time his assignment at the Junker factory was extended. In early September 1940, he was allowed to leave Halberstadt and visit his family for ten days. He wrote in his diary that while he was at home in Görlitz, he repaired twenty pairs of shoes, pickled one hundred cucumbers, took his children to the movies, and went on walks with his dear wife, Charlotte.[5]

Fig. 2 The GörlitzBranch Sunday School in 1938 (H. Habicht)

Fig. 2 The GörlitzBranch Sunday School in 1938 (H. Habicht)

The life of the children in the Görlitz Branch was influenced in a very special way by two women who are seen in virtually all Primary photographs taken during the war years. Jutta Larisch (born 1938) wrote of these two devoted sisters with great reverence:

[Baerbel Neumann] lived alone but was never alone. She was always seen in the company of children. She was the Primary president for many years. Her love and programs tied us all to the Church. She sold magazines for a living and must have left an invitation to children in every home she went to. She introduced many people to the Church. When she walked down the narrow sidewalks, there was never enough room for all the children who wanted to walk with her.[6]

About the other woman, Marietta Kulke Lehmann, Jutta wrote the following:

She was the director of our Görlitz Branch children’s choir. She had a lovely voice and [a] very attractive personality and a love for children. We wouldn’t miss trudging through the snow on our thirty- to forty-five-minute walk to church in order to be there for the children’s choir practice.

Unfortunately, under pressure from the government, the new Görlitz branch president, Felix Seibt, officially discontinued Sunday School attendance by children in early 1940. This must have been especially disappointing for sisters Neumann and Lehmann.[7]

Political programs such as the Hitler Youth were designed to include every child beginning at the age of ten. Therefore, despite physical challenges caused by a case of infantile paralysis, Helmut Habicht was inducted into the Jungvolk program and described his experiences as follows:

I was a member of the Jungvolk when I was ten years old, but the meetings did not interfere with our Sunday church meetings. For the most part it was a good experience because we . . . learned about our region, but as children we did not know what the aim of all this was. They did not openly talk about Hitler and the government but there were hints of it. When I was fourteen years old, I automatically advanced to the Hitler Youth and also participated in some of the things they offered, but it also never interfered with our meetings.

Horst Sommer (born 1926) turned fourteen in October 1940 and joined the Hitler Youth. Because many Hitler Youth groups had a specific focus, Horst chose a group specializing in cavalry training. Because of the random assignment of recruits to the various branches of the military, his training with horses was of little value to him when he was later drafted into the navy.[8]

The Jungvolk program was initially fun for Eberhard Sommer (born 1930), but as he attended more and more meetings, he found himself dissatisfied with the political drilling he experienced. “I detested saying ‘Heil Hitler’ and really started doubting what they were teaching us.”[9] He began to skip the meetings, preferring to spend his time swimming and boating on the river. He was picked up on several occasions by his leaders but was never severely punished.

The Görlitz genealogical research group during one of their wartime study sessions (J. Schmidt Runnacles)

The Görlitz genealogical research group during one of their wartime study sessions (J. Schmidt Runnacles)

On June 24, 1943, a Sunday, Eberhard was baptized in the Neisse River by President Felix Seibt. Eberhard’s father (not yet a member of the Church) was away in the army and gave his permission in a letter. He had opposed Eberhard’s baptism for several years, insisting that his son was not yet ready. Now he indicated that his son was prepared.[10]

In the first year of the war, Ruth Baier was engaged to marry Erich Hain, but his military service commitment prevented the wedding for several months. Finally, they married on August 6, 1940. She told of the event years later:

First, we went to the civil registration office [in city hall] and later had a little celebration with the entire ward. [Eric] got furlough for ten days for our wedding. Soldiers did not come home very often. We also did not go on a honeymoon because there was no money and there was not much to eat.

After Eric returned to his unit, Ruth continued to work with her parents in their beauty salon.

On December 29, 1941, little Vera Larisch (only fifteen months old) died of diphtheria. The diary entry recorded by her father, Anton Larisch, was predictably heartbroken. He journeyed home from Halberstadt to attend her funeral and ended up staying for two weeks to nurse his entire family back to health from various illnesses. Despite his enthusiastic missionary efforts in Halberstadt (where he was working to revive a dormant branch and was serving as branch president), being away from his family was tearing Brother Larisch apart.[11]

As the war progressed and German soldiers were dying in Europe, Asia, and Africa, a woman in the Görlitz Branch received successive word that her sons had been killed one by one. Ruth Baier Hain recalled how the branch members did their best to comfort this sister in her grief:

Sister Else Wagner had lost three sons and a son-in-law. We held a ceremony to honor her sons. There was prelude music, singing, and talks given by people who knew the sons. Sister Wagner could not say anything—she was deeply moved. I think she later expressed her gratitude to everybody who helped. She was very strong in the gospel and never blamed or doubted Heavenly Father. She did not have much money and was not physically strong, but she was a devoted sister.

Horst Sommer was inducted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst in August 1943. However, the needs of the Germany military were so intense at the time that his one-year term of duty was shortened to three months, and he was drafted into the navy. He later described his reaction to the assignment:

Serving in the navy was not my fondest wish. I was not thrilled to serve on a submarine. I thought that a hero could also be a man who said “no” sometimes. . . . Being in a submarine is like being inside a tank. There is no easy way to get out. . . . I was in a submarine for several hours [only one time] but was never on a real voyage.

Six decades later, Horst could still describe in great detail the process of exiting a submarine at depths up to six hundred feet.

Heinz Sommer (born 1921) was a mechanical engineer working at one of the two war factories in Görlitz. His employment exempted him from military service, but his younger brother, Eberhard, remembered later that Heinz felt guilty about being a civilian; other young men in the neighborhood were fighting and dying for their country while Heinz sat at work in his hometown. He finally gave in to local pressure and volunteered in 1943. He was assigned to the air force and did essentially the same thing in Italy that he had done back in Görlitz.

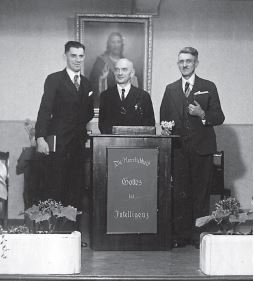

The letter every family feared: “It is my sad duty to inform you that your son, Heinz [Sommer] was killed while fighting partisans on April 30 [1944].” (H. Sommer)

The letter every family feared: “It is my sad duty to inform you that your son, Heinz [Sommer] was killed while fighting partisans on April 30 [1944].” (H. Sommer)

Heinz was killed in 1944. The official explanation was that he was fighting partisans in Italy. However, his brother, Eberhard, recalled hearing that Heinz was sitting at his desk designing motors for rockets when he was shot through the window by a partisan. The incident was never fully explained.[12] Eberhard was only thirteen at the time and had serious questions about the loss of his brother:

When my brother was killed, I asked the Lord why it could happen. I received a peaceful feeling about it. I remember my brother Heinz saying many times to me, “The gospel is true. Live the gospel—you will need it.” It stuck with me. I knew what he meant.

In the fall of 1944, the Soviet army invaded eastern Germany, and the flight of millions of German civilians began. Fred Larisch (born 1934) was ten years old at the time, but later clearly recalled watching refugees stream past their house in Görlitz:

For months prior to our leaving, we saw horses and wagons and people walking in a continuous stream. Our street was like a highway. They were refugees, and we didn’t know where they were coming from. They seemed to be in distress, not knowing where to go, but they were following continuous lines of refugees coming through, being sent by train into different areas. . . . Then all of a sudden, we found ourselves being refugees.[13]

“The war didn’t really come home to us in Görlitz until the last few months,” recalled Helmut Habicht, “Until then, life simply went on.” Then the government asked women and children to evacuate the city. With the men away in military service and with Helmut exempt because of his paralysis, he had become the principal priesthood holder of the branch. “I had to bless and pass the sacrament and preside over the meetings,” he explained. Fortunately, there were several other boys in the Görlitz Branch who were prepared to fill the roles of men within their families, such as Eberhard Sommer and Fred Larisch.

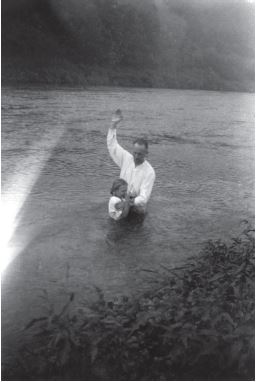

Ruth Larisch was baptized by her father in the Neisse River in 1940. (F. Larisch)

Ruth Larisch was baptized by her father in the Neisse River in 1940. (F. Larisch)

Fourteen-year-old Eberhard Sommer was asked by his mother to take charge of their departure from Görlitz. She told him that because he held the priesthood, he should make the main decisions, and she would follow. They boarded the last car of a passenger train standing in the Görlitz railroad station. Suddenly, Eberhard had the distinct impression that they had to get off the train, despite the fact that they had nice seats. His mother first resisted then yielded, and they moved to another car. The next morning, the train was attacked by dive-bombers, and the passenger car in which they were first seated was destroyed.[14]

Members of the Görlitz Branch posed for this photograph in 1942. (F. Larisch)

Members of the Görlitz Branch posed for this photograph in 1942. (F. Larisch)

Charlotte Larisch included the following statement in her autobiography: “On a Sunday morning in February, 1945, I gathered some clothes and pots and something to eat and put it in the baby buggy and set Gisela, who was almost two years [old] at that time, on top of it and walked with the children to the next town.”[15] Thus began the exodus of Sister Larisch and her children from Görlitz.

Ten-year-old Fred Larisch recalled that while his mother pulled the baby carriage, he and his sister Ruth pulled the family’s Leiterwagen.

Our Leiterwagen was from three to four feet long and about eighteen to twenty inches wide. The sides were like a ladder, with ribs. The rear wheels were about sixteen inches in diameter and the front wheels were smaller. We put everything that we possibly could carry on that wagon.

With the Red Army approaching, things looked very bleak for Sister Larisch and her children. Not only did she have to find a way to leave town and protect her children, but her husband had been arrested in January (charged with treason), and she had no idea where he was being held. However, conditions were about to change for the better, as she later wrote:

In that time of sorrow and worry, a wonderful thing happened. The six weeks for Anton’s arrest were over, and he was set free.[16] . . . He arrived at Görlitz at noon of the same Sunday that we left in the morning. He got his bicycle out of the cellar and tried to reach us. We did meet in [Löbau]; it was really a miracle because I did not know he was free and on his way to find us. . . . It seemed almost impossible for him to find us because he did not know where we went and there were so many refugees. When we met that day, we knew it was possible only through the help of our Father in Heaven.

Once they were reunited, the Larisch family made their way to Halberstadt.

Charlotte Larisch’s sister, Johanna Schmidt (born 1927), wrote detailed descriptions of the sad plight of refugees in the last months of the war. Shortly after leaving Görlitz, she and her mother were in Bautzen, trying to get to Halberstadt to join Charlotte. It appeared that they were on their way when they were crowded into boxcars and the train pulled out of the station. In her own words:

It was in the middle of winter, with no heat whatsoever in the boxcars, no washing facilities, no toilets, no food, absolutely nothing but thousands of people. . . . Nobody knew where we were going. The train stopped early in the morning so everybody could get out and stretch. After that, the train would stop every two or three hours to let us out and stretch, but then we were closed up again in the dark. That went on for three days and three nights in the dark and cold. Only once did we stop long enough to have some food cooked for us, and that was the only time we had something warm to eat. I can’t describe the feeling I had on that train. I am sure that everyone on that train felt the total despair that I did. When the train stopped I would walk around by myself and just pray, and when we were back inside the train I sat on top of our hard suitcases that were in the handcart to wait for the next stop, but there was no room to stand up and move around.[17]

Bernhard Habicht, Heinz Sommer, and Gunter Wagner were all killed in combat. (H. Habicht)

Bernhard Habicht, Heinz Sommer, and Gunter Wagner were all killed in combat. (H. Habicht)

When the journey ended, Johanna learned that they were in Czechoslovakia—nowhere near Halberstadt and headed in the wrong direction. Fortunately, they made their way to Prague and from there found a train heading back into Germany. Her story continued:

From there to the city of Halberstadt, we traveled under terrible conditions again for three days and three nights, changing trains thirteen times with no place to sit or sleep. . . . There was no way of knowing what the conditions would be like. I honestly don’t know how we managed. . . . As we finally arrived in Halberstadt, we were greeted by an air-raid alarm.

Finally united with her sister, Charlotte Larisch, Johanna Schmidt enjoyed a little security, but her trials were far from over. On Sunday, April 8, 1945, what she called “a few peaceful weeks” came to an abrupt end; another air raid reduced nearly all of Halberstadt to rubble in a matter of minutes. Her nephew, Fred Larisch, was looking out the apartment window. Suddenly, he yelled that bombs were falling, and everybody raced to the basement of the apartment house. Johanna recalled the event:

All around us the bombs exploded. This went on for about five to seven minutes, what seemed an eternity to us, and then all was quiet. . . . It was not long after that when we heard that next group of planes coming. . . . Nobody can imagine the horror that we felt as we sat there wondering if we were going to die. . . . This time it was a terrifying hissing sound and the air pressure from the explosions was so strong that we felt as if our eardrums would burst. We could feel the whole house shaking. It was so terrible that I wished and prayed with all my heart that I could die. I even told the Lord, “Oh, please, let the house collapse on us and kill us instantly.”[18]

Remarkably, the Larisch and Schmidt families survived the dreadful experience, as did all of the active members of the Halberstadt Branch.

The Görlitz Branch presidency during the war (from left): Kurt Lehmann, Felix Seibt, and Hermann Kulke (F. Larisch)

The Görlitz Branch presidency during the war (from left): Kurt Lehmann, Felix Seibt, and Hermann Kulke (F. Larisch)

When the American tanks rolled into the town of Langenstein (a suburb of Halberstadt) where the Larisch family lived in late April 1945, Anton went out to greet them. Because he had been studying English in night classes, he wanted to talk to them. According to Fred, “My father was asking them if any of them were LDS. All of the tanks stopped then. We didn’t find any LDS soldiers, but they gave us a lamb.”

There were no air raids in Görlitz until the end of the war, according to Helmut Habicht. Then things happened in rapid succession, and he had to seek shelter on about twenty occasions. One bomb did strike the meetinghouse, damaging the Relief Society room, but the other rooms were intact. Finally, the government requisitioned the rooms for use as housing for refugees. By the time the war ended on May 8, 1945, the remaining members of the Görlitz Branch were holding meetings in the apartments of two families. A few weeks after the war ended, the members were allowed to use the rooms at Emmerichstrasse 68 once again.

When the invaders entered Görlitz, Ruth Baier Hain’s mother decided to take a strong stand in the family’s defense. As Ruth later recounted:

We were home when the Russians first came into our house. My mother was very strong in her faith, and we were also. We prayed, and then the Russians did not steal any of our property. My mother approached them and asked firmly: “What do you want from us? My son-in-law helped Russian women, protected them while he was serving in Russia and shared his Christmas packages with them. What do you want from us now?”

The bold approach intimidated the soldiers, and they left the family in peace.

“I was not a prisoner until the war was over,” recalled Horst Sommer. His story continued:

We were captured by the British in Schleswig-Holstein. Many [German prisoners] were taken to Siberia, since they needed workers there. I worked for a farmer near Nienburg on the Weser for about a year until 1946. The next few steps on the way home led me through Wanne-Eikel where I worked in a coal mine.

Priesthood holders of the Görlitz Branch. Four of these men lost their lives in the war. (H. Habicht)

Priesthood holders of the Görlitz Branch. Four of these men lost their lives in the war. (H. Habicht)

During the summer of 1945, Johanna Schmidt felt compelled to return to Görlitz to determine the status of her home. Her trip from Halberstadt took her through a devastated and defeated Germany. She walked and carried heavy suitcases part of the way. Arriving in Görlitz, she went straight to her home. As Johanna recalled:

Oh, how it looked. Simply indescribable. I walked from one room to the next, and it was all just one big mess. There was not one piece of furniture that was not damaged or broken, and all of our clothes that we had left behind, as well as our mattresses, had been stolen. There had been a concentration camp about five minutes from our home, and when the prisoners there were released they naturally came into the homes and took what they needed and wanted. Nobody could really blame them for stealing, but they destroyed a lot too. . . . I walked through our garden and found pots and dishes broken, scattered all around.[19]

After cleaning up the home as best she could (“so that my mother would not have to see it like this”), she spent another week traveling back to Halberstadt.

Anton and Charlotte Larisch and Johanna Schmidt survived the immediate aftermath of the war in Halberstadt, though conditions there were deplorable. After five years of active attendance and missionary work in Halberstadt, Anton was set apart as the branch president there on June 1, 1945. A change in employment finally made it possible for him to take his family back to their hometown of Görlitz in February 1946.[20]

Heinz Sommer finally arrived at home on June 30, 1946:

My mother knew I was still alive, but she did not believe that I was actually standing in the house because she did not know when I was coming back. I didn’t write to tell my mother that I was on my way home because in those days so many men were shipped to Russia without notice that she would have looked for me to come home, and I might have been on my way to Russia.

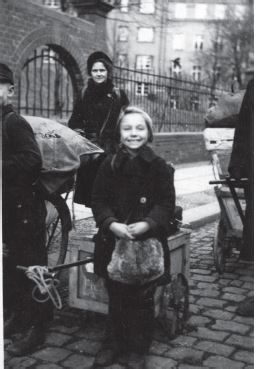

Jutta Larisch was happy to be home again in Görlitz in February of 1946. (F. Larisch)

Jutta Larisch was happy to be home again in Görlitz in February of 1946. (F. Larisch)

In reviewing his attitude as a Latter-day Saint under the harrowing circumstances of World War II, Helmut Habicht made this observation:

I think I had a testimony of the gospel of Jesus Christ, and it did not change during the war. It was strengthened because my father was not a member. My mother was a wonderful example of kindness and that was the gospel for me. . . . She was the ultimate example for me.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Görlitz Branch did not survive World War II:

Johanna Berger full-time missionary Berlin 1939–1941; m. —— Groth; k. in air raid Hamburg 1943 (Larisch; H. Sommer)

Rudolf Bernhard Habicht b. Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 21 Mar 1924; son of Richard Ernst Friedolin Habicht and Emma Marie Rachak; bp. 30 Jul 1933; ord. priest; Waffen-SS corporal; MIA Eastern Front Dec 1944 (Habicht; FHL Microfilm 162769, 1935 Census; IGI)

Karl Gustav Friedrich Kühn b. Leopoldshain, Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 4 May 1909; son of Karl Gustav Kuehn and Pauline Selma Hansche; bp. 23 Oct 1917; m. 17 Nov 1933; d. Russia 8 Mar 1944 (Habicht; IGI)

Karl Gustav Kühn b. Hermsdorf, Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 12 Oct 1866; bp. 29 Jan 1902; m. 18 May 1891, Anna Luise Auguste Hansche; 2 children; d. Leopoldshain, Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 25 Jul 1943 (IGI)

Vera Sigrid Erika Larisch b. Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 4 Oct 1940; dau . of Anton Larisch and Charlotte Anna Luise Schmidt Larisch; d. diphtheria 29 Dec 1941; bur. Görlitz 31 Dec 1941 (Görlitz Branch History, Anton Larisch diary, 25; AF; IGI)

Hedwig Lehmann b. Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 5 Apr 1892; dau. of Hermann Lehmann and Emilie Sommer; d. old age 13 Jul 1944 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 744–45)

Kurt Lehmann b. Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 29 Jul 1908; ord. elder; k. in battle Penzig, Schlesien 17 Apr 1945 (G. Lehmann)

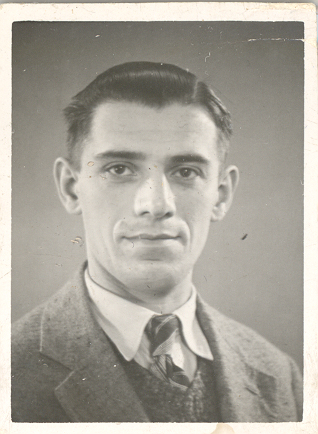

Kurt Lehmamn (H. Habicht)

Kurt Lehmamn (H. Habicht)

Ernst Friedrich Michalk b. Neupuschwitz, Bautzen, Sachsen 22 Nov 1919; son of Karl Traugott Michalk and Marie Martha Luecke; bp. 2 Aug 1929; m. 8 Jan 1944; d. 4 or 5 Mar 1945; bur. Kamp-Linfort Military Cemetery, Germany (Habicht; www.volksbund.de; IGI; AF)

Heinz Sommer b. Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 1921; son of Hermann Alfred Sommer and Else Böhme; ord. priest or elder; k. in battle northern Italy 30 Apr 1944 (W. Sommer; IGI)

Heinz Günther Wagner b. Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 28 Feb 1924; son of Johann Karl Wagner and Anna Elsa Lohse; bp. 30 Jul 1933; corporal; k. in battle 3 km west of Orlansk, Ukraine 28 Oct 1943; bur. Krassny-Bojez, Ukraine (H. Wagner; www.volksbund.de; FHL Microfilm 245291, 1935 Census; IGI; AF)

Hermann Heinrich Walter Wagner b. Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 7 Jan 1915; son of Johann Karl Wagner and Anna Elsa Lohse; bp. 13 Sep 1924; ord. teacher; k. in battle southeast of Metkowitschi, Russia 7 Feb 1944 (H. Wagner; FHL Microfilm 245291, 1935 Census; IGI; AF)

Wilhelm Rudi Wagner b. Görlitz, Schlesien, Preussen 1 Aug 1922; son of Johann Karl Wagner and Anna Elsa Lohse; bp. 27 Jul 1930; ord. teacher; k. in battle near Repky, Russia 12 or 14 Feb 1944 (H. Wagner; FHL Microfilm 245291, 1935 Census; IGI; AF)

Rudi Wagner (H. Habicht)

Rudi Wagner (H. Habicht)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Ruth Baier Hein, interview by the author in German, Görlitz, Germany, June 6, 2007; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[3] Helmut Habicht, interview by the author in German, Görlitz, Germany, June 6, 2007.

[4] Anton Larisch, diary, March 17, 1940, 7; private collection; trans. Ruth Larisch Hinkel.

[5] Ibid., September 6, 1940, 16.

[6] Jutta (Judy) Larisch Winkelmann to the author, letter, October 7, 2006; author’s collection.

[7] Because this kind of intervention is not mentioned by other eyewitnesses, the ruling must have come from the city government.

[8] Horst Sommer, interview by the author in German, Görlitz, Germany, June 6, 2007.

[9] Eberhard Sommer, biography (unpublished), 41; private collection.

[10] Eberhard Sommer, biography, 46.

[11] Anton Larisch, diary, December 29, 1941, 25.

[12] Eberhard Sommer, biography, 53.

[13] Fred Larisch, interview by the author, West Jordan, Utah, November 10, 2006.

[14] Eberhard Sommer, biography, 56.

[15] Charlotte Larisch, “The Story of Anton & Charlotte Larisch,” The Announcer (unpublished family newsletter, April 1971), 4; private collection. Anton Larisch had been arrested in Halberstadt (again and on the same spurious charges) and had been transferred to a prison in Berlin in January 1945.

[16] See the Halberstadt Branch chapter for the story of Anton Larisch and his troubles with the law.

[17] Kenneth Runnacles and Johanna Schmidt Runnacles, “Our Lives,” (unpublished family history, about 1977), 52; private collection.

[18] Ibid., 54.

[19] Ibid., 58.

[20] Larisch, “Story of Anton & Charlotte Larisch,” 5.