Freiberg Branch, Dresden District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 250-8.

Freiberg, located eighteen miles southwest of Dresden, was a key silver-mining town in the Erzgebirge Mountains and had a population of thirty five thousand in 1939. The state of Saxony that included Freiberg was the home to more members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints than any other state in Germany; the districts of Dresden, Chemnitz, Zwickau, and part of Leipzig had a total of twenty-three branches. More than 3,100 of the 7,608 Saints in the East German Mission lived in that relatively small area.

| Freiberg Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 17 |

| Priests | 4 |

| Teachers | 10 |

| Deacons | 17 |

| Other Adult Males | 20 |

| Adult Females | 96 |

| Male Children | 13 |

| Female Children | 13 |

| Total | 190 |

The members of the Freiberg branch just prior to the war

The members of the Freiberg branch just prior to the war

At the onset of World War II, the branch met in rented rooms in a Hinterhaus at Marienstrasse 4. Judith Hegewald (born 1924) later described how the Saints gained access to the rooms:

The front door [of the main building] was always open, and in order to reach the Hinterhaus, we just walked through the front door and then the corridor. We did not have a sign at the door saying that we met there. People lived in the front of the building, and when we walked through the corridor, we could see a garden on the left. On the right side we walked into [our rooms].[2]

Dorothea Henkel (born 1932) later recalled the arrangement of the rooms:

It was one big room that we remodeled; it used to be a factory. We had dances in there, we had meetings in there, we held everything in that one big room, and then we had three classrooms. And we had the cloakroom and one little room they used as a kitchen with a connection for a two-flame gas burner.[3]

Ingrid Henkel (born 1937), Dorothea’s sister, recalled that the floors were oiled wood. “We could never sit on the floor when we were kids. We had to be very careful with our clothes. And we had no indoor toilets, just outhouses.”[4]

Heinz Hegewald (born 1931) remembered specific décor in the chapel:

We had a wonderful picture of the prophet Joseph Smith (his profile) on the wall at the right of the congregation. And on the podium, we had a picture, a motif from the Bible. And also, we had a verse embroidered on the pulpit “Love one another.” And on the right side of the chapel was a picture with Christ knocking on the door.[5]

Regarding the branch meeting schedule, Judith Hegewald recalled:

The first meeting was Sunday School in the morning, then we walked home and had some lunch and rested. In the evening hours, we walked back because sacrament meeting started at 7:00 p.m. After that meeting, we held our choir practice from 8:30 to 9:00. . . . During the week, we went to church two more times. We went for Relief Society and priesthood meeting and to MIA on a different [evening]. Primary was on Wednesday afternoon.

The family of Wilhelm Henkel lived on the northern outskirts of Freiberg in a suburb called Lössnitz, where the parents had built a two-story home in the 1930s at Schulweg 3F. They walked about forty-five minutes to church twice each Sunday—for Sunday School in the morning, then home for dinner, then back to church for sacrament meeting in the evening.

Heinz Hoeke (born 1930) recalled an average attendance of perhaps eighty to one hundred twenty persons (in a room that could accommodate about one hundred fifty persons). According to his account, the branch choir always sat at the front of the room.[6] Paul Kleinert was the branch president during the war years.

With both LDS Primary and Jungvolk (the first phase of the Hitler Youth) meetings being held on Wednesday afternoons, Heinz Hoeke found a way to be punctual for both meetings: he simply wore his Jungvolk uniform to Primary.

Former Freiberg branch president Wilhelm Henkel (right) as a soldier in Marseilles, France in about 1942 (D. Henkel Roscher)

Former Freiberg branch president Wilhelm Henkel (right) as a soldier in Marseilles, France in about 1942 (D. Henkel Roscher)

Judith Hegewald was not allowed to join the Bund Deutscher Mädehen. Although her father, district president Max Hegewald, was a member of the Nazi Party (as required by his employment at the court in Freiberg), he was not a supporter of the Nazi youth programs. Judith recounted what happened when BDM leaders came to the home to inquire about her absence: “My father explained that I would be needed at home helping to take care of my siblings [because] I was the second oldest.”

At age ten, Dorothea Henkel was inducted into the Jungvolk program, along with her schoolmates. The activities included learning about the life of Adolf Hitler, folk dancing, handicrafts, collecting for the winter relief fund, making toys for poor people, marching in parades, and participating in athletic festivals. As she later recalled, “I sometimes missed meetings, but I didn’t get in trouble because my father was gone [in the military] and my mother was pregnant, so I had to help my little sister.”

The Hegewald brothers experienced some difficulties as members of the Jungvolk organization. Rudolf (born 1930) recalled having some German youth meetings on Sunday:

If possible, we would go after the Hitler Youth meeting to our sacrament meeting in our brown shirts and our belts across the chest and a knife at our side. And all we did was take the knife off and pass the sacrament in Hitler Youth uniform with the swastika armband.

For a while, things became very difficult for another Hegewald boy, Gerhard. According to Rudolf:

My brother Gerhard and I were in the same meeting where there were about a hundred youth, and the leader pointed to us and said we were the saboteurs because we would go to church sometimes on Sunday instead of to the Hitler Youth meeting, and he mentioned to the mass of young people that he hoped that they knew what to do with the saboteurs.

Apparently the boys did “know what to do”: Gerhard was beaten up soon after that meeting.

Dorothea’s father, Wilhelm Henkel, was a shoemaker by trade. Toward the end of 1939, he received a mission call from Berlin but was prevented from serving when drafted into the German army in January 1940. With the exception of a few home visits on furlough, Brother Henkel was absent from Freiberg for the remainder of the war. Dorothea recalled having to wait until she was nine years old to be baptized because she wanted her father to baptize her. The ceremony finally took place at Soldiers Pond near Freiberg on October 23, 1941.

Even in wartime, there was time to be a child, as Dorothea later described:

We played all kinds of fantasy games and fairy tales; we didn’t need lots of clothes to dress up in, just our imaginations. Just a scarf and a hat maybe; we just had great times. I wasn’t a tomboy, but I played with the boys, climbed trees, jumped over walls, things like that.

Heinz Hoeke also had a good time as a child in Freiberg. He recalled playing soccer and enjoying all kinds of sports. He also played soldier (“I was always the commander!”). At the age of twelve, he was baptized a member of the Church in September 1942.

Judith Hegewald was inducted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst in 1942 at the age of eighteen and spent six months in the service of her country. While in Plauen, she received a letter regarding her brother, Clemens:

The letter said that my brother had died, and I was allowed to go home for three days. They did not tell us how he died, but they sent a written letter. We wore black for a while afterwards. I wore a black ribbon around my arm over my uniform. My father gave a talk in sacrament meeting and wept terribly. . . . Even an entire year later, I dreamed of [Clemens] every night. He always smiled at me in those dreams, and he was happy. I cried a lot during that time, but it seemed like those dreams [came] to comfort me.

After her release from the Reichsarbeitsdienst, Judith went to work in Leipzig for the military for a time. Later, she accompanied her father, the district president, as he visited other branches. She explained, “He wanted me to meet somebody in the Church, so he took me with him sometimes when he went to Görlitz. I met three young boys, but they all died in the war.”

Clemens Hegewald was killed in Russia in December 1942. (M. Hegewald)

Clemens Hegewald was killed in Russia in December 1942. (M. Hegewald)

The Dzierzon family lived in Grossschirma, about five miles from the meetinghouse. They walked or rode their bicycles to attend church. During the war, Erich Dzierzon met a young lady who was a member of the locally dominant Lutheran church. He recalled that

It was a case of love at first sight, and I told her that if we were going to be together then it would be best if we had one religion. She . . . accepted the gospel as soon as I told her about it. We were married during the war and our daughter, Gisela, was born during the war.[7]

Willi Dzierzon spent several years on the Eastern Front and wrote later that his life had been spared on several distinct occasions. Once he was sent with a message to the next village, and while riding his horse toward a long, low hill, heard a quiet but clear voice say, “Stop!” He stopped and examined the ground around him. A recent rain had exposed several antipersonnel mines to his view. “That was the first time my life was saved.”[8]

On another occasion, Willi was again on horseback, approaching an abandoned concrete artillery bunker. The dirt road split, one track leading downward in front of the bunker and the other leading upward behind the bunker, both tracks uniting again on the other side. He later explained that he should have spared his horse the effort necessary to take the upper road but took the more difficult path anyway. Just as he was next to the bunker, an artillery round landed on the lower road exactly on the opposite side of the bunker, such that the bunker shielded him and his horse from the shrapnel from the shell. “I would have been killed or maimed,” he later concluded.

Ingrid, the second Henkel daughter, recalled that her mother served as the Relief Society president of the Dresden District throughout the war. She took the train to visit other branches in the district, sometimes taking a daughter along. When Sister Henkel traveled alone, another woman in the branch looked after her children.

Rudolf Hegewald remembered very clearly the attack on Freiberg on October 7, 1944, “because it was my grandmother’s birthday,” he explained. They actually watched the attack from an upstairs window:

We were sick and tired of air-raid warnings when nothing happened. All those years from ’39 to ’44, nothing happened to our little city, so we didn’t listen to the sirens anymore. When the alarms would sound, we would just watch these bombers come, 30,000 feet or higher with the big condensation trails.

But on this day things were different. The boys watched bombs fall as close as three hundreds yards down the street. According to Rudolf, “The pressure of the explosions lifted the roof tiles, and they made a terrible noise, a clattering noise. We were down in the basement in a matter of seconds.” After the attack, people all over town went out to survey the damage. “Some people had been decapitated by the explosions. It was a terrible sight.”

Heinz Hoeke also recalled the attack of October 7 in vivid detail:

We knew that the war had come home to Freiberg that day. I was at work and remember how the sirens began to wail. We first thought that nothing would happen because there had been alarms before. Then somebody said that bombs were falling, so we hurried down into the basement. If a bomb had hit the building, we would not have survived.

In the fall of 1944, a Russian laborer came to board with the Henkel family. At first, Sister Henkel, whose husband was still away in the military, was scared that the young man (about twenty-two, according to Dorothea) would be unclean and dangerous, but they learned otherwise. He turned out to be an opponent of Stalin and swore that he would commit suicide if the Red Army caught up with him. He even attended church once or twice, Dorothea remembered.

The Freiberg Branch met in rooms in the Hinterhaus attached to this structure throughout World War II. (I. Henkel Rudolph)

The Freiberg Branch met in rooms in the Hinterhaus attached to this structure throughout World War II. (I. Henkel Rudolph)

As the war neared its end, refugees from eastern Germany streamed through Saxony on their way west. As Heinz Hegewald recalled:

In our [church] meeting, we were asked to take some families in, and my mother, bless her heart, she was a true Christian, and even though there were eight of us at home, almost ten, with the parents and the grandma, she took in the Arndt family who had been bombed out in Berlin. We spared one room for this family—Sister Arndt and her sons, Hans Joachim and Dieter.

Latter-day Saint refugees came to Freiberg from far away. The Naujoks and Augat families of the Tilsit Branch in the Königsberg District (East Prussia) arrived in early 1945 and were put up in the church rooms at Marienstrasse 4. According to Heinz Hegewald, “they were always mothers and children. Never a husband or father. These were terrible times, but the Lord helped us.”

As the Third Reich neared collapse in January 1945, Rudolf Hegewald witnessed something quite startling. He told this story:

Let me give you another little experience I had concerning the destruction of the Jewish race in Germany. Often people ask us whether we knew. Well, I tell you, in 1945, in January, I saw a terrible picture I will never forget. Down our street, SS [soldiers] had surrounded about three hundred Jewish women, their heads shaven, and they herded them down the street with German shepherd dogs, just like cattle. And then I thought, “What is happening in Germany?” They couldn’t kill them where they were, so they drove them farther inland, and this was the first time that I noticed that Germany had committed an unspeakable crime. I knew that the women were Jewish because they all wore their Jewish star [Star of David].

In early 1945, Dorothea Henkel became personally aware of the horrors of war, not because of attacks on Freiberg but because victims of the firebombing of Dresden were brought to Freiberg for treatment. She was in the hospital recovering from an appendectomy when Dresden was attacked on February 13–14. When the burned and injured filled the hospital, Dorothea was sent home to recuperate. She vividly recalled her reaction when the Dresden people arrived: “All those burned people, those injured people from Dresden. It was horrible! They brought a lady into my room; she was badly burned. It was terrible!”

Because she was sent home from the hospital early, Dorothea did not heal well. Her incision became infected and the stitches would not come out properly:

Sometimes I was really down, and then we had a home teacher come, and he gave me a blessing, and I went to the bathroom, and here I pulled another stitch out. That went from February till August—six months until that healed.

Rudolf Hegewald and his father, Max Hegewald, rode their bicycles to Dresden two weeks after the bombing

To see what happened to the members, and we found the ones in the Altstadt—the old core of the city. The Altstadt was wiped out, and we saw the corpses still lying in the streets, and then they were shrunk, maybe that big [two feet], an adult (when they burn, they shrink), and they were black corpses, just lying in the street at that time—two weeks later.

Hans Joachim Arndt was one of the few eyewitnesses to tell of military training associated with his time in the Jungvolk:

Toward the end of the war, the last two months, they actually trained us in our Hitler Youth programs, how to use real weapons. We shot rifles, we learned how to throw grenades, they were telling us the usual slogans of “this is the battle to the bitter end,” and they wanted us to be prepared for that.[9]

Fortunately, Hans Joachim and his schoolmates were never required to be soldiers in the lost cause of keeping the Soviet soldiers from conquering Freiberg.

Rudolf Hegewald recalled how the war directly threatened him during March and April of 1945, when Allied airplanes enjoyed total air superiority and flew over Freiberg looking for targets:

After church, when we went home, we would have to look and know where the airplanes were. If we could see the airplanes, we assumed that they could see us so we would hide. If we didn’t see the airplanes, then we would run from house to house to get home safely. And as a matter of fact as a young fourteen-year-old, I went out in the fields to see the dive-bombers better, and then if I saw them come, I would throw myself down and take some grass to cover me up so they wouldn’t shoot at me. This is a vivid experience I had in 1945 right before the war ended.

“I was drafted into the Volkssturm [home guard] on April 15,” recalled Heinz Hoeke. He reported for duty the next morning and was transported into the Erzgebirge Mountains. When they heard that their destination was Czechoslovakia, Heinz and several other boys had no desire to go there, so they jumped on a truck bound in a different direction. They had deserted, and if they had been caught, the consequences could have been fatal. Fortunately, the boys eventually were able to take a train back to Freiberg without being captured.

Before the Red Army entered Freiberg, they fired on the city with their artillery, in response to the last German defensive efforts. Dorothea Henkel had gone to a local dairy to get a can of milk, and on her way home she narrowly missed injury when a piece of shrapnel landed next to her. “The next thing we knew, the Russians were coming out of the forest, so we hid in our cellar,” she recalled. “Our neighbor across the street was a communist. He came out and greeted the Russians with open arms, and the Russians just looked at him and took his watch and walked off. It was funny.” Heinz Hoeke remembered hearing the roar of the enemy artillery when he was on his way home from Church on May 7. When the invaders entered the city the next day, there were twenty persons (mostly refugees) living in the home with Heinz’s family. One day, they had a serious scare:

A Russian officer came into our apartment, saw all of the young women, and told us that they were beautiful. Then he left. He must have told others, however, because that night many soldiers came looking for those women. They were hiding in the bathroom, so the soldiers did not find them.

As refugees, the Arndts of Berlin had few possessions when they were taken in by the Hegewald family. Hans Joachim Arndt recalled that they took great care to preserve certain personal documents:

We had a collection of important documents we always [kept] with us. My mother actually stowed those underneath the seat of a four-legged stool. And this stool went with us everywhere we went. We carted it with us, and it had those documents stored in the seat. I remember, that’s how we kept those things. I’m not sure whatever happened to the stool, but the documents survived.

Sister Henkel and her three daughters lived in the cellar of their home for three weeks, while the rooms upstairs were inhabited by thirty enemy soldiers. There were several frightening moments, but “the Lord took care of us,” according to Dorothea. “We didn’t have a war raging in our town like the bombing in Dresden, just a minor thing, but we had the Russians in our houses. Those were perilous times for everybody. But the Church was there. We could always go to church.”

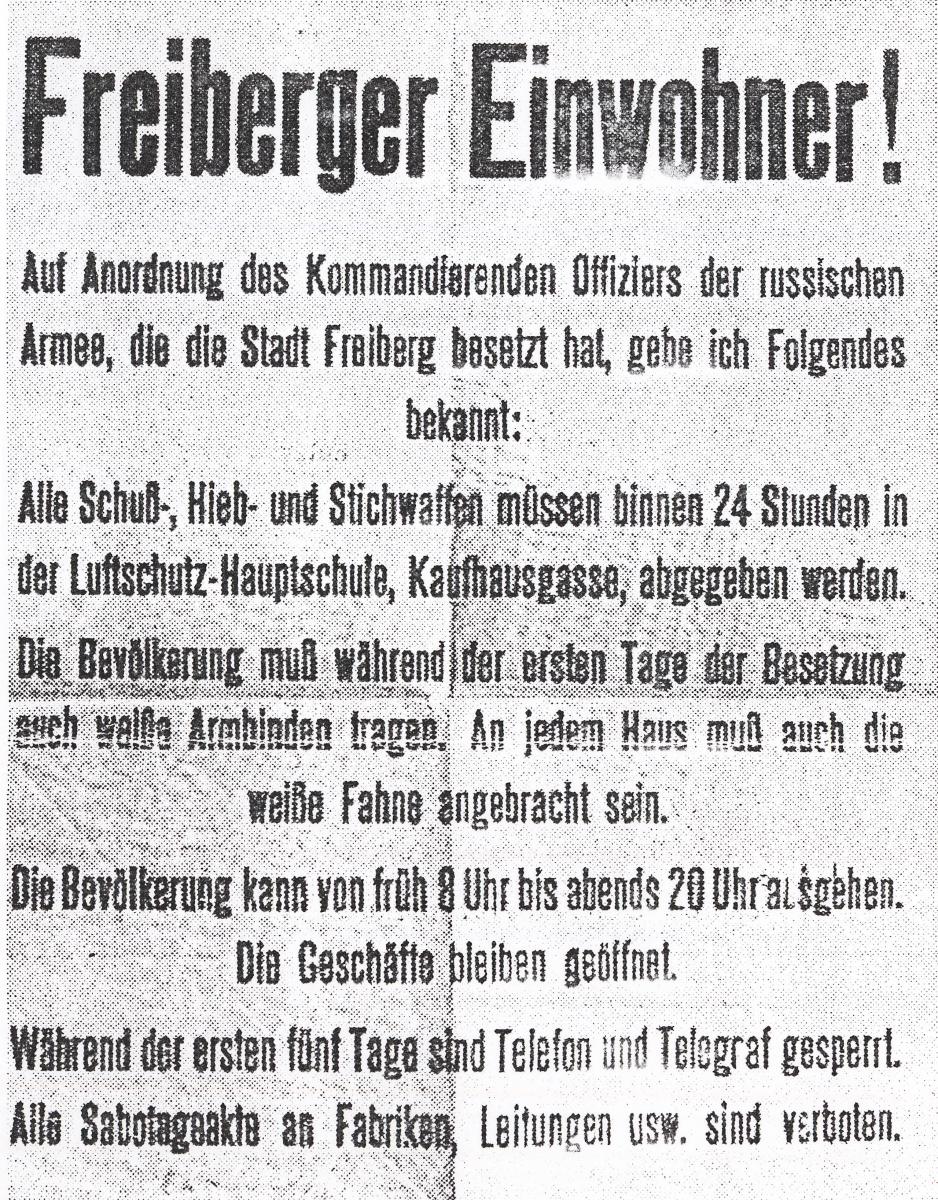

Residents of Freiberg!

By order of the commanding officer of the Russian army that has occupied the city of Freiberg, I announce the following: All firearms, swords and military knives are to be surrendered at the main civil defense school at Kaufhausgasse within 24 hours. During the first days of the occupation, civilians must wear white armbands. A white flag must be displayed on every building. Civilians may be on the streets from 8:00 a.m. to 8:00 p.m. Stores are to remain open. During the first five days, telephones and telegraph machines are not to be used. All acts of sabotage against factories, utility lines etc. are forbidden.

Some Saints believed that the end of the war meant the end of all of their problems. According to Rudolf Hegewald, “When the Russian army arrived, they came down our street—Gabelsbergerstrasse—and we hailed them as liberators. We were happy to have them in town. We could now finally sleep at night in our beds—no more air raids.” Unfortunately, Rudolf soon realized that “we had gone from the frying pan into the fire.”

[The soldiers] had permission from the Soviet commander to plunder and to rape and to do anything they wanted, and to steal, and so at nights, they would break into our apartments. We had to hide our sisters—we had four sisters—and our mother at nights. We would hide them in the garden, someplace in the bushes, because [the soldiers] would enter the houses and try to find females.

The reaction of Judith Hegewald, Rudolf’s sister, to the invasion was more frightful:

The Russians came in large groups with their tanks. It was horrible for us to see them walking up the Gabelsbergerstrasse. We were scared and did not know what would happen. They came by at night and went through houses searching for women. They also tried to come into our building. All of the families in our building stayed strong together.

Heinz Henkel described his impression of the common enemy soldier: “He was out to get three things: watches, bicycles, and women.” Millions of Germans in the area occupied by the Red Army would agree with his assessment, but others would add many household appliances to the list of items stolen.

Once the war ended, members of the Freiberg Branch longed for the return of husbands, fathers, and brothers. Gisa Henkel (born 1943) was only four years old when her father, Wilhelm Henkel, returned from a POW camp in France in November 1947. It was a confusing event, as she later explained:

He was skinny, but he was pretty healthy. I didn’t know him. When he came home I was still in a crib. And he came home and my mom was so excited, and she came in—it was midnight, and he said, “Oh, look who’s home!” And I said, “Yeah, an uncle!” And my mom said, “No, it’s your dad!” And I said, “No, it’s an uncle!” And over and over my mom said, “It’s your dad!” and I said, “No, it’s an uncle!” And my dad had a salami that he had gotten somehow, and he showed me the salami, and I said, “That’s my dad!”

Wilhelm Henkel had been away from his family (except for a few short furloughs) for seven years and ten months.

Looking back over his life during the war, Erich Dzierzon stated:

I served in the German army for seven war years, in Poland, in France, and in Russia, and came home without a scratch, which was a miracle. . . . During the war, I had neglected my church duties, and now that the war was over, I had to repent and make up for lost time.[10]

Erich’s confession that he had neglected his church duties should not be judged harshly. The probability that a German soldier who was a Latter-day Saint would meet another soldier of the same religious affiliation was so low that stories of such meetings are very rare. Latter-day Saint German soldiers almost never served in areas where they could attend church and were usually totally isolated from the Church while in uniform.

Regarding the spiritual survival of the Saints in Freiberg during the war, Rudolf and Heinz Hegewald shared the following conclusions:

The gospel was their anchor. That was the only thing they had to hang on to in order to survive. That is the truth. Even the destruction of Dresden and the killing of many members down there, it did not make the surviving members bitter. We all knew and had the testimony that they were in a better place now. We were under the influence of the old fashion Mormons—the pioneers. This was typical German style—you hold on to the testimony, on to the gospel. There was no question about it.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Freiberg Branch did not survive World War II:

Anna Helene Eilenberger b. Großhartmanndorf, Dresden, Sachsen 3 Jun 1889; dau. of Ernst Louis Eilenberger and Anna Marie Reichelt; bp. 27 Jun 1921; m. Großhartmannsdorf 3 May 1914, Bruno Hermann Baessler; 2 children; d. Gränitz, Dresden, Sachsen 21 Dec 1942 (IGI)

Ernst Louis Eilenberger b. Großhartmannsdorf, Dresden, Sachsen 29 Feb 1856; son of Karl August Eilenberger and Juliane Wilhelmine Bellmann; bp. 8 Nov 1911; ord. elder; m. Großhartmannsdorf 31 Aug 1879, Anna Marie Reichelt; 14 children; d. Großhartmannsdorf 20 May 1940 (Sonntagsstern, no. 21, 23 Jun 1940 n. p.; IGI; AF)

Ernst Heinrich Geistert b. Rudelstadt, Schlesien, Preussen 23 Oct 1849; son of Karl Gottlieb Jeremias Fehst and Beate Christiane Geistert; bp. 23 Apr 1905; ord. elder 1923; d. old age Freiberg, Sachsen 6 Sep 1939 (Stern no. 21, 1 Nov. 1939, 340; FHL Microfilm 25773, 1935 Census)

Clemens Carl Hegewald b. Freiberg, Dresden, Sachsen 18 Jan 1923; son of Max Otto Hegewald and Margarete Martha Uhlig; bp. 7 Nov 1931; soldier; k. in air raid Newel, Russia 16 Dec 1942; bur. Newel, Russia (Heinz Hegewald; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Robert Herrmann Hegewald b. Cämmerswalde, Dresden, Sachsen 16 Sep or Nov 1871; son of August Wilhelm Hegewald and Emilie Wilhelmine Meyer; bp. 1 Jul or Aug 1919; ord. elder; m. Liddy Thekla Hemmig; d. Freiberg, Dresden, Sachsen 5 Apr 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 22, 1 Jun 1941, 88; FHL Microfilm 162780 Census; IGI)

Hermann Heinrich Henkel b. Lietzen, Brandenburg, Preussen 19 Mar 1911; son of Friedrich Wilhelm Henkel and Auguste Marie Ruttke; bp. 29 Mar 1932; m. Frankfurt/

Johannes Walter Jakwerth b. Freiberg, Dresden, Sachsen 6 Dec 1922; son of Josef Jakwerth and Linna Emma Kasper; rifleman; k. in battle Rava Ruska, Galizien, Russia 25 Jun 1941; bur. Potelitsch Cemetery, Ukraine (D. Henkel; www.volksbund.de; PRF; IGI)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Judith Hegewald, interview by the author in German, Schwerin, Germany, June 11, 2007; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[3] Dorothea Henkel Roscher, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, April 14, 2006.

[4] Ingrid Henkel Rudolph, interview by the author, Sandy, Utah, July 26, 2007.

[5] Rudolf Hegewald and Heinz Hegewald, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, January 19, 2007.

[6] Heinz Hoeke, interview by the author in German, Highland, Utah, February 10, 2006.

[7] Erich Dzierzon, Gisela Dzierzon Heller, and Manfred Heller, “Gospel and the Government,” in Behind the Iron Curtain:Recollections of Latter-day Saints in East Germany, ed. Garold N. Davis and Norma Davis (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 287–88.

[8] Willi Dzierzon, “Some Faith-promoting Experiences in Russia,” (unpublished manuscript, about 1949); private collection.

[9] Hans Joachim Arndt, interview by the author, Sandy, Utah, November 10, 2006.

[10] Dzierzon, Heller, and Heller, “Gospel and the Government,” 287–88.