Frankfurt-Oder Branch, Spreewald District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 434-40.

About sixty-five miles east of Berlin, the city of Frankfurt lies on the west bank of the Oder River. An industrial city, it was the home of about 75,000 people when World War II began.

| Frankfurt-Oder Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 7 |

| Priests | 0 |

| Teachers | 1 |

| Deacons | 3 |

| Other Adult Males | 9 |

| Adult Females | 38 |

| Male Children | 6 |

| Female Children | 4 |

| Total | 68 |

The Latter-day Saints of the Frankfurt-Oder Branch were led in 1939 by Walter Krause, who had arrived in the city in 1931, married there, and fathered three children. As an independent carpenter, he led a modest life and was a devoted branch president. Just prior to the war, the branch held its meetings in rented rooms at Park 11–12, on the main floor of the Hinterhaus.

“The rooms were in an old factory building,” said Ilona Gertrud Henkel (born 1940). “Some of the members lived in the same building.”[2]

An interesting entry is found in the history of the East German Mission under May 18, 1938:

On this, the previous and the following day, special meetings were held in Frankfurt an der Oder, Cottbus and Forst Branches, Spreewald District, by [missionary] Elder Edward R. McKay, to discuss the new genealogy plan, which was presented at that time.[3]

As it was elsewhere in Germany, the work of genealogical research in support of temple ordinances for the deceased was being carried out with enthusiasm in the Spreewald District.

At the onset of the year 1939, the Frankfurt-Oder Branch had strong adult priesthood leadership, but younger priesthood holders were rare. More than one half of the branch membership consisted of women.

In 1938, Walter Krause was classified as “conditionally fit” for military service. When the war began, he was thirty years old and relatively confident that at his age he would not be needed for the war effort. This hope was dashed in January 1940 when he was drafted into a police unit. He later wrote of his feelings at the time: “Nobody mentioned how my family would survive or what would happen to my shop or all the work I was doing for the branch. I was disappointed but what good did that do?”[4]

Walter was posted to occupied Poland and soon found himself assigned as a cook (something he had never done before). For the next three years, he served under safe conditions well away from the front. He informed his comrades of his avoidance of alcohol and tobacco and sought opportunities to speak with them about religion. He even prayed with other Christians and delivered funeral sermons for fallen friends.[5]

Young Manfred Henkel (born 1933) grew up with the Third Reich, but his parents were not comfortable under Hitler’s government. Manfred recalled problems using the required salutation “Heil Hitler!” and wrote this description:

We were very careful about what we said during the Hitler years. . . . We didn’t really like saying “Heil Hitler” all the time. When my mother sent me [to the store]—I might have been nine at the time—I said “Guten Tag,” and they sent me out and said that I could come back in when I was ready to say “Heil Hitler!”[6]

Members of the Frankfurt-Oder Branch in the late 1930s (Der Stern, May 1993)

As if there were not sufficient ways for a family to suffer in wartime, an accident took the life of ten-year-old Winfried Henkel in 1943; he drowned while swimming in the Oder River by Frankfurt. According to his younger sister, Ilona, “My father had been drafted into the Wehrmacht, and he was not allowed to come home for the funeral.”

As a soldier, Walter Krause was probably not the best example of obedience. He found too often that the actions of soldiers were not in harmony with the teachings of the gospel. On one occasion, for example, he watched as his commanding officer knocked a piece of bread from the hand of a Russian child and crushed it in the dust with his heel. Walter could not contain himself and yelled, “You jerk! Our children and grandchildren will pay for such deeds!” Walter was led away in handcuffs, but a higher-ranking officer prevented punishment. On another occasion, he was ordered to shoot an old man and some children who were suspected partisans. He refused to do so, insisting that they were not partisans. The officer responded, “If you refuse to carry out my order, you will be shot along with them.” But the officer did not dare follow through with his threat.[7]

Brothers Karl and Hermann Henkel were stationed in Norway for a time and were actually able to attend the meetings of a branch of Saints there. Hermann became well acquainted with the Jacobsen family in Oslo.[8]

Walter Krause became a successful and popular cook and was rewarded at times with additional leave to visit his family. However, by 1943, he lost his comfortable assignment. That year he was wounded twice as his unit retreated before the advancing Red Army. All in all, he was blessed with the fulfillment of a sincere wish, namely never having to shoot at the enemy.[9]

In the absence of Brother Krause, Karl Baukus directed the affairs of the branch until he, too, was drafted. During the war, several involuntary laborers from the Netherlands attended meetings with the members in Frankfurt-Oder. Due to the lack of priesthood leadership, district leaders from Cottbus and Forst also visited on several Sundays.[10]

As a young girl, Ilona Henkel did not understand the complexities of war, but she understood, to a degree, the plight of a Jewish family who lived in the same building: “My mother always told me that we were not allowed to give them anything to eat though they were hungry. [But] she gave them food because she felt that we were so blessed that she had to share with others.”

Life during wartime in Frankfurt-Oder was fairly comfortable until the last year when air raids plagued the city and the invaders approached. Manfred Henkel recalled, “We lost our home in 1944. . . . The windows in our apartment were blown out, and we moved out to live with my grandparents until the place could be repaired.” Things then went from bad to worse for Maria Henkel, whose husband, Hermann Heinrich, was away at the front. Manfred recounted:

Frankfurt-Oder was declared a fortress during the last months of the war and most of the members left town. Some of us took the last train out of town and went to Annaberg-Buchholz. It was an adventuresome trip. Members there took us in. Then the place we were staying was hit and burned out with the last of our property.

Margarete Krause later wrote of a particular tragedy among the members in Frankfurt-Oder:

When the Russians came, Sister Jenny Reinemann chose to take her life along with her son[’s], Georg, and her daughter[’s], Regina, by taking poison. Regina survived the event, having developed immunity to the drug; she had taken it previously for a nervous condition.

In early 1945, Walter Krause was assigned to guard an ammunition train moving toward Germany. When Walter’s unit was attacked by Polish partisans, the wagon on which Walter was riding collapsed, and he was crushed underneath large boxes. Taken for dead, he was nearly buried by his comrades but saved by an alert medic. Walter’s injuries were extensive and he was removed from the front lines for treatment.[11]

Following his recovery, Walter was ordered to accompany a railroad car full of documents and equipment back to Germany. He and a friend made it as far as Dresden, where they arrived in the Neustadt district at precisely the wrong time—a few hours before the terrible firebombing of February 13–14, 1945. When a railroad train loaded with ammunition exploded nearby, Walter lost the hearing in his left ear. He and his comrade survived and traveled on to the south and west in the Erzgebirge Mountains. He hoped that he would find his wife and his children there.

Margarete Krause had indeed left Frankfurt-Oder when the Red Army approached. With several other Saints, she found her way to the town of Annaberg-Buchholz near the Czechoslovakian border. In the late spring, she left that town and traveled east to Cottbus where she joined the LDS refugee colony at the Fritz Lehnig home.

Walter and his friend decided in April 1945 that the best way to survive was to change into civilian clothing and hide out in the forest. They easily could have been shot by fanatic police for not actively contributing to the hopeless defense of the fatherland. During this time of uncertainty, Walter wrote the following in his diary:

Heavenly Father, what is to become of all these people [refugees]? Wilt thou ever again grant them peace? Will they ever have the opportunity to hear of Thy gospel? . . . Today I truly cannot comprehend thee. Why do so many innocent people, old and young, have to suffer because a few madmen lived a riotous life and started a murderous war? . . . Only thou, oh, Lord, canst remedy this situation and I beg thee to do so.[12]

Eventually, Walter and his friend surrendered to American soldiers. During his initial interrogation, he found himself talking with an officer who demanded to know if Walter was a fascist. His response was to show the officer a certificate proving his membership in the Church. The American knew quite a bit about the LDS Church in Utah (his brother was a member of the Church) and asked for information regarding LDS beliefs as proof. Walter’s answers were satisfactory.

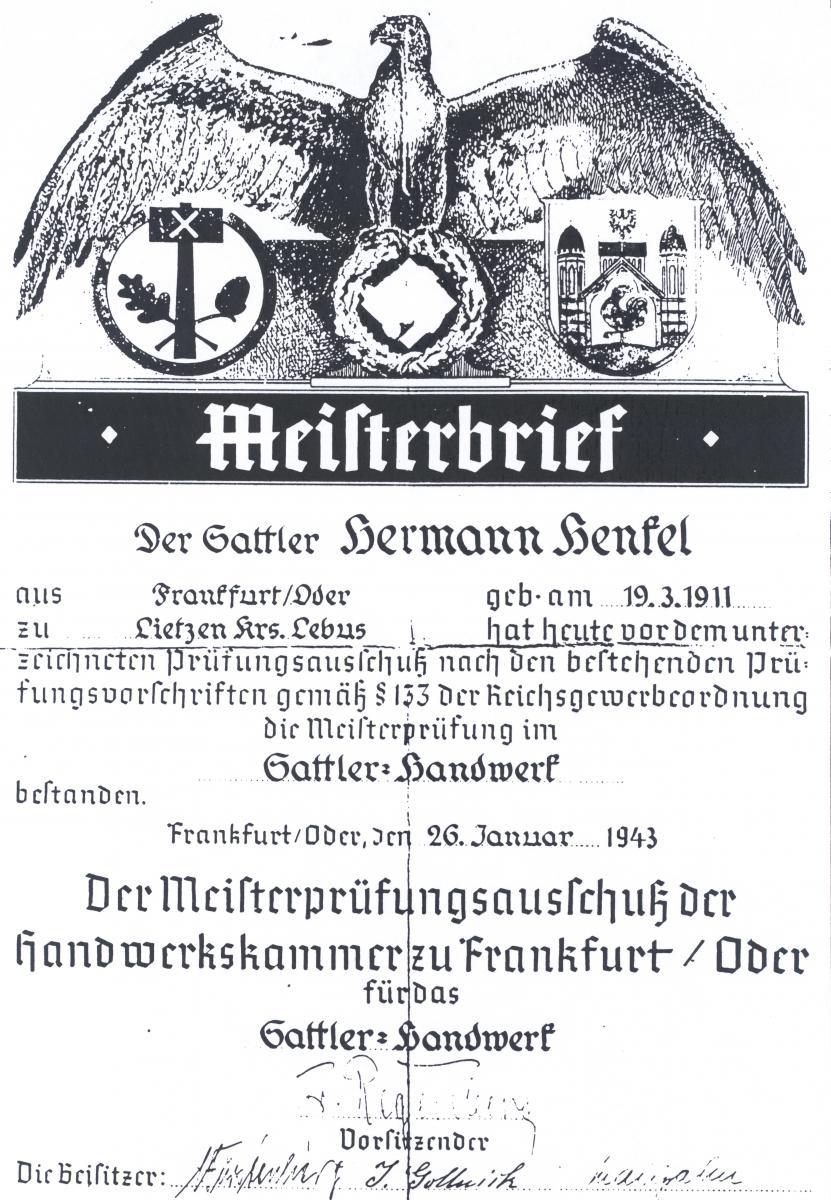

Hermann Henkel became a master saddle maker in 1943. This document recognizes his status in the guild. (M. Henkel)

Hermann Henkel became a master saddle maker in 1943. This document recognizes his status in the guild. (M. Henkel)

The Henkel family had to leave their home on the east side of the Oder River. That territory had been ceded to Poland, and they were not allowed to stay. The exodus to the west and south must have been a real adventure to little Ilona, who described part of their journey in these words:

I remember taking the train for a short distance and sitting on top of the train. . . . Often we stopped in the middle of nowhere. When we were forced to walk, we were glad to meet people with handcarts who let us put our backpacks on them so we did not have to carry them for so long. . . . It seemed chaotic and none of the [transportation] systems seemed to work anymore.

According to Ilona, her mother changed residence at least five times in the next few years, including short stays in the Latter-day Saint refugee colonies of Cottbus and Wolfsgrün. An uncle eventually found an apartment for them in Freiberg, Saxony, where they joined the strong Latter-day Saint branch.

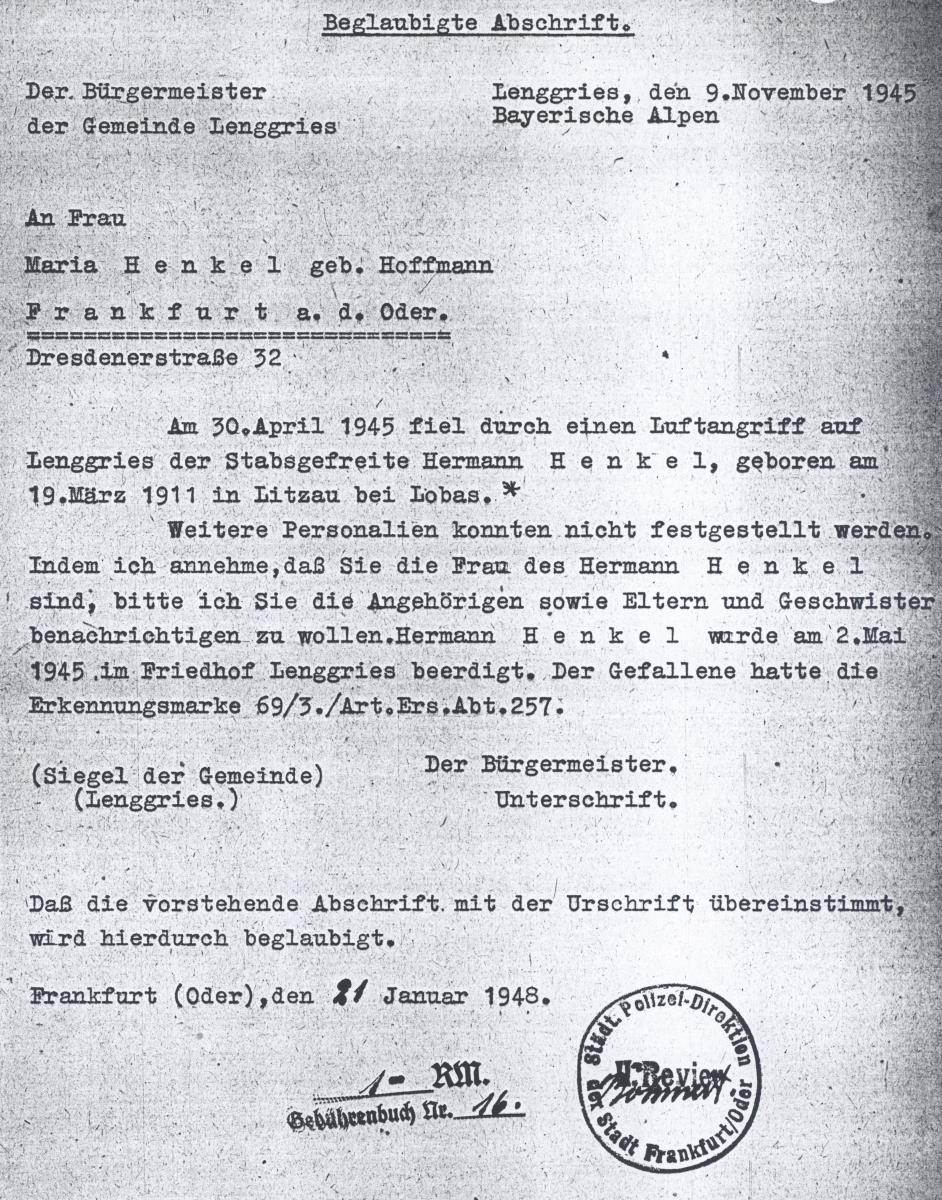

Manfred Henkel explained the fate of his soldier father, Hermann Heinrich Henkel, in these words:

My father died in the war, on April 30, 1945, in Lenggries, Bavaria, Germany. I have the death certificate. It says that he was Catholic, but that is not correct. His papers were in his pocket, and he apparently was wounded near that pocket and the blood got on his papers and they could not tell what he was. He was buried in the Catholic cemetery in Lenggries.

This letter dated November 9, 1945, was the first official notice of the death of Hermann Heinrich Henkel just days before the war ended. (M. Henkel)

This letter dated November 9, 1945, was the first official notice of the death of Hermann Heinrich Henkel just days before the war ended. (M. Henkel)

Brother Henkel’s death is extensively documented. The mayor of Lenggries wrote to Marie Henkel in November 1945 to inform her of the burial of her husband there. One month later, an army comrade wrote to her and indicated that her husband had died quickly. Nearly seven years later, she received word that her husband’s remains had been removed to a military cemetery in Traunstein near Munich in Bavaria.

In June 1945, Walter Krause was anxious to find his family but found himself assigned as a military policeman in the tiny town of Brünlos in Saxony. He was charged with keeping order among the populace and preventing violence on the part of fanatics. When the Red Army assumed authority in the region a few weeks later, his assignment was confirmed (he was even offered the job of mayor of the town but declined). By July, he was fortunate to be released and was miraculously accompanied by Soviet officers by train to Cottbus, where he knew his family was staying. The reunion with his wife and his children took place under the Lehnig roof in early July 1945. Walter had avoided becoming a prisoner of war and was pleased to join the LDS refugee colony in Cottbus.

Very few of the wartime members of the Frankfurt-Oder Branch were able to return to their homes. For the next few years, the branch struggled to survive.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Frankfurt-Oder Branch did not survive World War II:

Karl Ferdinand Baukus b. Magotten, Ostpreussen, Preussen 24 Jan 1888; son of Johann Ferdinand Baukus and Maria Plaehn; bp. 7 Jun 1934; m. Hafstrom, Kalgen, Ostpreussen, Preussen 13 Jan 1916, Theresia Luise Murningkeit; 3 children; d. field hospital Wandern, Halbe, Brandenburg, Preussen 31 Dec 1945 (M. Henkel; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Hermann Heinrich Henkel b. Lietzen, Brandenburg, Preussen 19 Mar 1911; son of Friedrich Wilhelm Henkel and Auguste Marie Ruttke; bp. 29 Mar 1932; m. Frankfurt-Oder, Brandenburg, Preussen 15 Dec 1932, Frieda Marie Hofmann; 4 children; staff corporal; k. in battle Lenggries, Bayern 30 Apr 1945; bur. Traunstein, Oberbayern, Bayern (M. Henkel; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Hermann Henkel’s remains were moved to this military cemetery in Traunstein, Germany, in 1952. He may be the only LDS soldier of the East German Mission buried in what is now Germany. (R. Minert, 2008)

Hermann Henkel’s remains were moved to this military cemetery in Traunstein, Germany, in 1952. He may be the only LDS soldier of the East German Mission buried in what is now Germany. (R. Minert, 2008)

Winfried Karl Henkel b. Frankfurt-Oder, Brandenburg, Preussen 19 Nov 1933; son of Karl Friedrich Henkel and Gertrud Elsa Hofmann; bp. Frankfurt-Oder 1941; drowned in the Oder River, Frankfurt-Oder 3 Aug 1943; bur. Frankfurt-Oder (I. Henkel-Hartz; FHL Microfilm 162781, 1935 LDS Census)

Wolfgang Karl Georg Reinemann b. Frankfurt-Oder, Brandenburg, Preussen 25 Jan 1928; son of Karl Reinemann and Jenny Sophie Wilke; k. in battle Berlin, Preussen 30 Apr 1945; bur. Berlin-Wilmersdorf, Schmargendorf Cemetery (M. Krause; www.volksbund.de)

Jenny Sophie Wilke b. Berlin-Weis, Brandenburg, Preussen 5 Aug 1903; m. Karl Reinemann; 3 children; d. suicide Frankfurt-Oder, Brandenburg, Preussen Jan-Feb 1945 (M. Krause; FHL Microfilm 271401, 1930/

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Ilona Gertrud Henkel Hartz, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, February 22, 2008; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[3] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 22, East German Mission History.

[4] Edith Krause, Walter Krause in seiner Zeit (Hamburg: Mein Buch, 2005), 59.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Manfred Henkel, interview by Jennifer Heckmann in German, Bretzfeld, Germany, August 17, 2006.

[7] Edith Krause, Walter Krause, 63.

[8] Manfred Henkel to the author, letter, August 17, 2006.

[9] Edith Krause, Walter Krause, 59, 73.

[10] Margarete Krause, Gemeinde Frankfurt an der Oder (unpublished history); private collection; trans. the author.

[11] Edith Krause, Walter Krause, 69–70.

[12] Ibid., 72–73.