Forst Branch, Spreewald District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 425-34.

Numbering 142 members, the branch in Forst was by far the largest of the four in the Spreewald District. The city is situated on the west bank of the Neisse River but in 1939 included homes on the east side of the river in what is now Poland. As World War II approached, there were about 45,000 inhabitants in Forst.

| Forst Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 7 |

| Priests | 2 |

| Teachers | 2 |

| Deacons | 11 |

| Other Adult Males | 21 |

| Adult Females | 85 |

| Male Children | 7 |

| Female Children | 7 |

| Total | 142 |

The meetings of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints were held in rented rooms at Frankfurterstrasse 17 in the Hinterhaus. Helga Schäler (born 1930) recalled that the building looked like a factory.[2]

We were on the second floor, and we had it fixed up as a meeting place. There was a little stage and some classrooms. When you came in, there was a cloakroom with a tiny little iron stove that would keep it warm.

Eberhard Gäbler (born 1927) added these details about this meeting place:

There was a sign out front, at the right of the portal where we drove through to the Hinterhaus. We were in the third floor [classrooms]. We could play ping-pong up there too. We had a cloakroom that was used as a classroom. The main room had a stage, and another classroom was behind that. Attendance may have been sixty or seventy. That location was used by the branch during the entire war. [3]

Sunday School was held at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting in the evening. As was the case in many wartime branches, Helga recalled, “A lot of times the young kids stayed home, and the older people went to sacrament meeting in the evenings.”

The history of the East German Mission shows the following entry for Wednesday, May 18, 1938:

On this, the previous and the following day, special meetings were held in Frankfurt an der Oder, Cottbus and Forst Branches, Spreewald District, by Elder Edward R. McKay, to discuss the new genealogy plan, which was presented at that time.[4]

Apparently, all Church programs of that era were operating successfully in the Forst Branch.

Another entry in 1938 leaves room for speculation—Saturday, November 26 and Sunday, November 27: President and Sister Rees attended special meetings in the Forst and Guben Branches, spoke, and “brought new enthusiasm and cheer into the hearts of the attending members and friends.”[5] One wonders what may have dampened the spirits of the members in those days.

Morale among the citizenry in Germany in 1939 was predominately positive but not for those few Jews who had not yet left the country. Helga Schäler recalled experiences with a Jewish family who lived down the street from her Forst home. Three boys from that family attended LDS Church meetings, and Helga’s mother, Rosa, was their teacher. Later, while Sister Schäler worked as a cleaning lady at city hall, she met the mother of that Jewish family, who was being incarcerated temporarily in the basement. The woman was despondent and asked, “Sister Schäler, why does this happen to us? We have never done any harm to anyone?” Helga recalled her mother quietly weeping as she told her husband, Georg Schäler, of the situation.

The building in which the Forst Branch met during the war as it now appears (H. Schäler Price)

The building in which the Forst Branch met during the war as it now appears (H. Schäler Price)

Günther Gäbler (born 1923) had a positive experience in the Hitler Youth organization. He enjoyed the road trips, the camping, and the singing. “There was no heavy-duty political training,” he later explained. At sixteen, he began an apprenticeship as a carpenter and was able to complete it, despite interruptions caused by the war.

Eberhard Gäbler was in a cavalry unit of the Hitler Youth and enjoyed his training with horses. His brother, Horst (born 1932), did not have time for the organization because he was busy delivering newspapers during the last years of the war.

Irmgard Gäbler (born 1935) turned eight in 1943 and was baptized in the Neisse River. “I remember being swept away by the current, but my father [Bruno Gäbler] grabbed me and saved me.” A year later, she wanted to join the Jungvolk, but her mother objected.[6]

Shortly after the war began, Helga Schäler turned ten and was inducted with her classmates into the Jungvolk. She explained her reluctance to participate and described a strategy she developed to avoid attending the meetings:

I hated it. They threatened that the police would come for us if we didn’t go. Once a leader found me at the store, took me home, and then escorted me to the meeting. If you lived on the fourth floor, you could watch the street from the window and see [other girls] coming [to] hide in the attic.

Despite the shortages of war, Christmas celebrations were still observed at church, according to the recollections of Helga Schäler. Traditionally, a Christmas program was held and involved all of the children. The story of Christmas was told, songs were sung, and poems were recited. Santa Claus came with his sled or on a white horse and handed out sacks with presents. “If we didn’t know a poem to recite, we didn’t get any presents.”

Doris Schäler (born 1933) was seen by her school teacher while walking to church on several Sundays. Once, she stopped Doris and asked where she was headed. When the teacher found out that Doris attended church, the little girl was subjected to an inquiry in school. Doris later described the experience in these words:

In front of the entire class, she asked me if my father was in the [Nazi] Party. I answered honestly and said no. Then she asked if my mother was in the Nazi Party women’s auxiliary. I again said no. Then she asked if anybody in my family would support the country by being in the army or in other organizations. I answered that my brother was in the Wehrmacht. After that, she seemed satisfied and left me alone.[7]

As in nearly all branches of the East German Mission, most of the young men in Forst were drafted into the Wehrmacht but enough older men were still in town to guide the branch and exercise the powers of the priesthood. For most of the war years, Paul Schulze was the branch president. At the conclusion of the war, Georg Schäler (who was exempt from military duty due to poor health and eyesight) led the branch.

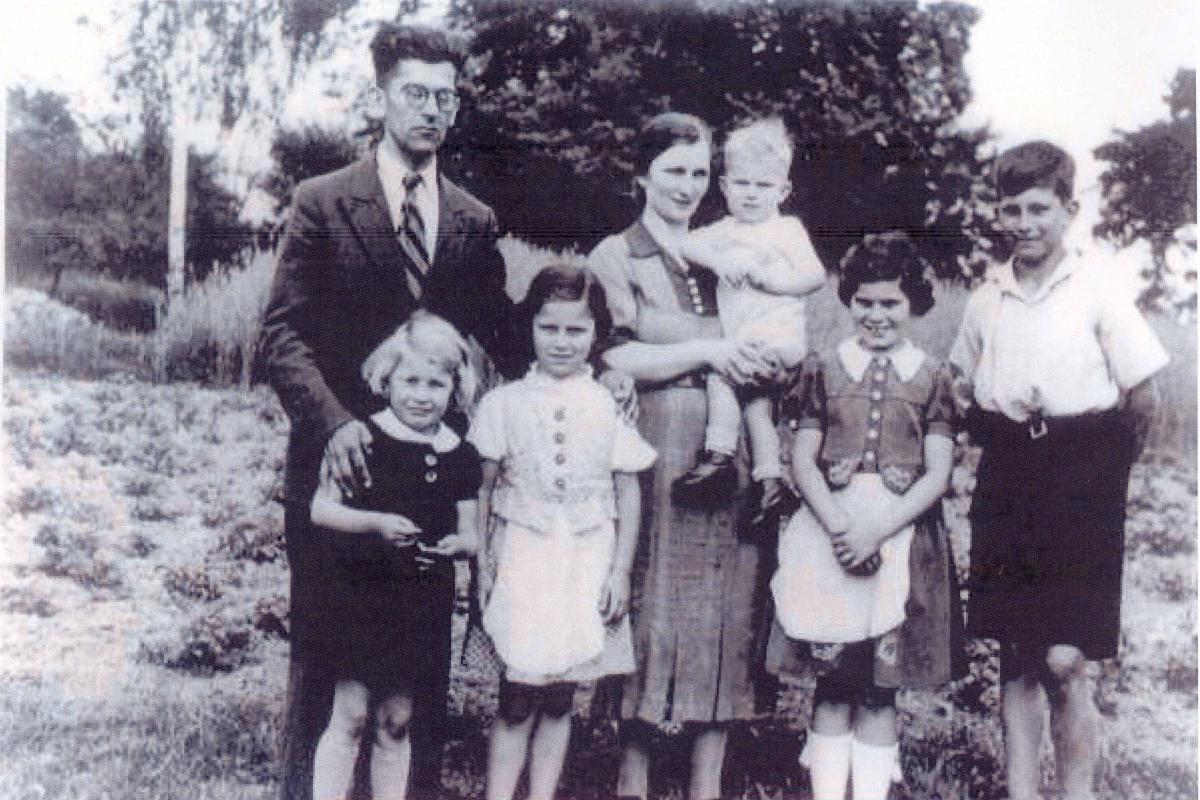

The family of Georg and Rosa Schäler in 1939. Brother Schäler was unfit for military service, because it was said that without his glasses “he could not distinguish between friend or foe.” (D. Schäler Shepardanis)

The family of Georg and Rosa Schäler in 1939. Brother Schäler was unfit for military service, because it was said that without his glasses “he could not distinguish between friend or foe.” (D. Schäler Shepardanis)

The Schäler family lived in several different apartments during the war years. At first, they were in the main part of town close to church then they moved across the river to a suburb called Berge. The walk from there to church was substantially longer, “about forty-five minutes, through the whole city,” as Helga recalled. She also said, “Basically, all I remember about being young was the war. It lasted from about the time I was eight until I was nearly fifteen.” However, she also indicated that she and her friends had plenty of opportunities to play and live a somewhat normal life:

We didn’t have television or even a radio at first, so we went outside. We went to the river and the woods; we loved the outdoors. We used to get coins and put them on the railroad tracks and wait until the train ran over them. When you picked them up, they would be about twice the size of normal. Once we were playing in the woods and it rained and we got all wet. We took off our clothes and hung them in the trees to dry, and when they were dry we put them back on.

During his six months in the Reichsarbeitsdienst, Günther Gäbler served aboard three ships, two of them being the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. Just a week after his release, a draft notice arrived, and he was inducted into the Wehrmacht. His basic training took place in Zülichau, Brandenburg, and from there he was transferred to a unit bound for Africa.[8] He was next trained in the use of light and heavy machine guns and arrived in Africa on July 30, 1942, to serve under Field Marshall Erwin Rommel.

In Africa, Günther and his comrades actually used captured British weapons to fire upon British tanks. Nevertheless, the German campaign in North Africa was a failure, and Günther was captured on October 25, 1942. After six months in a POW camp in Egypt, he was shipped to the United States. The voyage took him east to Bombay, then west and south along the east coast of Africa, past Capetown, across the Atlantic, around Cape Horn, along the coast of Chile, through the Panama Canal, and up the east coast of the United States to New York City. The extensive voyage lasted nearly two months.

The Forst Branch met in the upstairs rooms of this building behind the main building at Frankfurterstrasse 17. (R. Minert, 2008)

The Forst Branch met in the upstairs rooms of this building behind the main building at Frankfurterstrasse 17. (R. Minert, 2008)

Aboard the Cape Horn Castle, the German POWs had managed to make and hang out swastika flags without their captors finding out. This embarrassed the British crew when they docked in New York City. As Günther later recalled, “The British then [turned us over] to the Americans, [telling us] that we should make life as hard for them as we had made it for the British. The British were always nice to us; that I have to admit.”

After a long train ride (“very comfortable—leather seats!”), Günther found himself in Alberta, Canada, where he worked from 1943 to 1944. Then he volunteered for a logging detail and remained at that job through 1945. His pay was fifty cents per day or thirty marks per month. He was allowed to write as many as two letters and four cards per month, so his family knew of his whereabouts in North America before a notice arrived in Forst reporting him missing in action in Africa.

For most of the war, the city of Forst was spared air raids. Helga Schäler recalled the first time a bomb—apparently a dud—was dropped on the city:

They showed it in the city hall, and we went to look at it. We were basically very lucky that we did not have any bombing (hardly at all) until the very end when the Russians came in, and then everything went kaput.

As in many cities with large factories, Forst was a city where Dutch and Polish laborers were brought to work. Horst Schäler (born 1937) recalled that his mother invited a few foreign laborers to join the family for Sunday dinner each week, although food supplies were short. One Sunday after dinner, a man in a long leather coat knocked on the door and identified himself as an agent of the Gestapo. He had heard that foreign laborers had been in the apartment and wanted to know what was going on there. Rosa Schäler told him, “Mister, we invite them for Sunday dinner. We are Christians, and we believe that one should be kind to prisoners of war.” He replied, “Is that all?” then searched the apartment for radios and similar items. Finding only the standard Volksempfänger radio, he was satisfied and left.[9]

As the war drew to its conclusion, Eberhard Gäbler and his Hitler Youth group were pressed into service to dig trenches on the east side of the river for German defensive troops. However, Eberhard was no longer at home when the invaders arrived. The country needed soldiers, so he was not drafted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst but directly into the Wehrmacht at age seventeen. His military career was quite short and fairly uneventful, as he recalled:

It was the end of 1944, and I was assigned to an antiaircraft battery. I had quick basic training in Schleswig-Holstein, then went to an airfield up by Eckeberg by the Danish border, then was assigned to an airfield near Schleswig [in Germany] at Easter 1945. I was there when the war ended. We were attacked by both bombers and dive-bombers. When the Allied planes headed for cities in the interior, the fighter planes stayed around our area and tried to find our planes on the ground to destroy them. I was in the air force [ground troops]. We didn’t see the enemy until the war was over. My life was never really at risk, but twice while I was at the gun, our barracks were destroyed (a few hundred yards from our gun position).

Johannes (Hans) Georg Schäler was eighteen when he was drafted into the Waffen-SS. His younger brother, Horst, recalled the instruction their mother gave to Hans before he left home as a soldier:

She said that if he had to take a life in order to defend his own, that would be all right. But if he did not need to defend his own life, he was not to take the life of another person. My brother promised my mother that he would not kill anybody who was innocent, but that he would defend himself.

Hans Schäler was wounded in the Battle of the Bulge, spent some time in a hospital, then went home to Forst on leave in early 1945. When it came time for him to return to his unit in western Germany in the spring of 1945, railroad service was interrupted by air raids, and his departure was apparently delayed. According to his sister, Doris, Hans was jailed by the military police:

My parents tried desperately to convince the police that he was not a deserter. My father met one of Hans’s former teachers and explained the problem. . . . The teacher, also a soldier at the time, wrote a letter to the Wehrmacht. . . . My father then asked me to take the letter to the commander. I was eleven years old. I asked if I had to go, and he said that I had to go. I delivered the letter. The commander looked at me, took the letter, and told me that I could leave. They released my brother that same day.

The last general meeting of the Forst Branch in wartime was a conference of the Primary that was attended by seventy-five people on February 11, 1945. According to Eberhard Gäbler, “It was a spiritual event in peaceful harmony.” Days later, the German army retreated to the west bank of the Neisse, and the Soviets moved to the outskirts of Forst (to the suburb of Berge). In their apartments between the armies, the four Latter-day Saint families living east of the river were starving and prayed specifically that they might find food. Soon after the prayer was offered, Red Army artillery shell hit a supply depot, and German soldiers crossed the river to the Schäler apartment with substantial supplies of food that otherwise would have been wasted.

Members of the Forst Branch celebrated the centennial of the Relief Society in 1942. (H. Gäbler)

Members of the Forst Branch celebrated the centennial of the Relief Society in 1942. (H. Gäbler)

With this direct answer to prayer in mind, the children of those families gathered to pray for something they had not seen for a long time: chocolate. They had faith that their prayer would also be answered. It was, the answer coming unwittingly with the help of Hans Schäler, then a soldier defending his own hometown. According to his younger brother, Horst, Hans found a large supply of chocolate in a bombed-out and abandoned store downtown and gathered up some to take home. The prayer of the children was answered as expected. As Horst considered the event years later, he commented that “the Lord always used other people to help us; those other people might have thought that those events were only coincidences, but those things were a little too obvious.”

As little boys will do, Horst Schäler played soldier in his neighborhood in the days prior to the Soviet invasion. On one occasion, he found a grenade and tucked it into his belt, not realizing that the pin had been removed. A passing German soldier grabbed Horst by the collar, took the grenade from him, and threw it as far as it could. Fortunately, it did not explode. “He then put me across his knee and gave me a really good spanking,” recalled Horst.

When the Red Army approached Forst, the Schäler family thought that the German defenders would stop the invaders. As Helga recalled, “We thought we wouldn’t be like the other refugees and have to leave, but we had to do that, too.” They left their home on the east side of the Neisse River and moved in with an LDS family (the Voigts) on the west side. Two of the Schäler girls—Ruth and Helga—later decided to go back across the river to their apartment to retrieve the family accordion. Doris later called this a “foolish” plan and described what happened in these words:

Off they went to the river to cross the bridge, which was ready to be blown up. The soldiers did not want Ruthie to cross the bridge because it was much too dangerous. She begged for 15–20 minutes, which was granted reluctantly. She literally flew across the bridge, while Helga cowered in a trench praying with all her heart for the safety of her sister. Ruthie ran up the four flights, grabbed the instrument, which was heavy, ran down toward the bridge again, almost passing out from this effort. The German soldiers were truly relieved when she returned.[10]

The German defenders of Forst put up stiff resistance for several weeks, holding on to the bridgeheads on both sides of the river. However, their resources were simply not sufficient to hold off the invaders, and they retreated across the river to the main part of town in February 1945. The enemy arrived in the Berge suburb with such speed that young Horst Gäbler was surprised to see them. He had delivered his newspapers one evening and asked his aunt Dora to go home with him. As they crossed the bridge to the east bank, they were suddenly confronted by an enemy soldier, who first fired a warning shot, then (fortunately) allowed them to pass without hindrance. Aunt Dora was not a believer but learned the importance of prayer while hiding in the Gäbler’s basement shelter for the next few days.

The effort to recover the accordion was rewarded shortly after the invaders arrived in Forst. When a soldier bent on evil deeds entered the basement room where the Schäler women were hiding, they convinced him to leave them undisturbed and take the accordion as his great prize instead.

During the war, the population of Latter-day Saints living in Berge on the east bank of the Neisse River consisted almost totally of the families of Paul Schulze, Max Riedel, Georg Schäler, and Bruno Gäbler. In February 1945, Brother Gäbler gathered his family for prayer to ask the Lord’s guidance about whether to go or stay. The answer received by all seemed to be unanimous: “We’re staying here!” they decided. The Schulzes also stayed, while the Schälers and Riedels evacuated the neighborhood. Irmgard Gäbler was not quite ten at the time but vividly recalled what happened when the Soviet soldiers arrived in the neighborhood:

The day came when we were to be forced out of our homes. The Russians acted as if they were going to kill all of us. Then they marched us out of town into the forest. My father had a briefcase with all kinds of genealogical papers, and he brought them with us. He kept it all the way—[thirty] miles out [east] and [thirty] miles back. He was mocked for bringing such a thing along, but those were all of the genealogical papers about my ancestors.

The residents were marched thirty miles eastward by the conquerors and lived in the country for about the next two months. Horst Gäbler later described what transpired next: “We came back home in April 1945. Much of the housing was burned down, including our home. The town was destroyed 85 percent. We then lived in a neighbor’s house because they had fled.”

It was a Sunday in April when Red Army soldiers reached the place where the Schäler family was staying. They could hear sporadic firing and hid in the basement. At one point, Georg Schäler took his wife and his children upstairs to the living room and held a sacrament service with them around a little table. Then he told his family that Heavenly Father would bless them so that they would not need to be afraid. They sang and prayed together, after which Rose Schäler said that if they were righteous and did everything the Lord wanted them to do, they would someday go to America. A few minutes later, the soldiers searched the house and stole some of the Schäler’s property, but did not harm them.

“In about mid-February, the first Russians came into our house,” wrote Charlotte Schulze. “They were clean and spoke broken German.”[11] The next enemy soldiers were not as nice and Charlotte went into hiding. Her father was in the Volkssturm and her sister was working in a communications office. A few weeks later, Charlotte, her mother, and her siblings headed east toward the town of Pförten, passing horrible scenes of dead soldiers and decaying animals along the way. After a walk of nearly twenty miles, they stopped and searched for a place to stay while enemy soldiers watched. “Never have I prayed so fervently,” she later wrote.

A few days later, Charlotte and her mother were thrown into a cellar and incarcerated there with other women. One by one, the women were taken away and assaulted. The two Saints held fast to each other and prayed to the Lord for help. “Peace overcame our hearts, and we felt that nothing would happen to us; and so it was.” This was not the last time when the danger of molestation was imminent, but Charlotte was spared every time.[12]

The Schulze women eventually went fifteen miles north to Bobersberg, then south back to Sommerfeld, then finally west back to Forst. The town was policed by both the Soviets and the Polish, but the women were able to cross the river and find a place to stay with the Voigt family in Nossdorf. “We had lost literally everything, but nobody could take from us our faith and our testimonies,” Charlotte later wrote.[13] Her father was missing, and the family later heard that he too had been sent east of Forst at the end of the war; he had died of starvation as a prisoner of the conquerors.

Eberhard Gäbler later functioned as the unofficial historian of the Forst Branch and, in 1995, compiled stories under the title Gemeinde Forst Vor 50 Jahren—1945 (“The Forst Branch Fifty Years Ago—1945”). The following are extracts from that history:[14]

Sunday, February 18: We met in the Voigt family home. . . . We are in God’s hands.

Friday, February 23: People are confused and hopeless. . . . The Schulze family are missing. . . . We are praying for them.

Sunday, February 25: Flames seen in Nossdorf. . . . We are worried about the members living there.

Monday, February 26: The Lord blessed us in a wonderful way today: we received food for the first time in a long time. . . .

Wednesday, February 28: [Several members] moved from the city to Nossdorf today. [Several more] left for Niederbarnim by Berlin.

Friday, March 2: Today we were told “Women and children are to leave the city.” . . . We all felt like we need to stay and trust in God.

Saturday, March 3: We met for a fast meeting at 6:00 p.m. We prayed for all of the members . . . There were sixteen in attendance.

Sunday, March 4: Fast meeting. Elder Paul Schulze spoke to us: “[So far] the destroying angel has passed over us.”

Thursday, March 15: Life in the homes of the Saints goes on. Many members have taken non-members [refugees] into their homes.

Sunday, March 18: Sunday School at 10:00 a.m.; at 3:30 we held a memorial service for Brother Wolfgang Dommaschk who died on 23 January 1945 for Führer, Volk, und Vaterland.

Sunday, March 25: We held Sunday School and sacrament meeting. Reinhold and Betha Schwier were again with us after being absent for a while. All were pleased at the reunion. 22 persons were in attendance.

Saturday, March 31: We left Forst . . . with heavy hearts.

According to Eberhard Gäbler, the first postwar meeting of the Forst Branch took place on May 20, 1945, in the home of Sister Kolo:

In addition to the hostess, the following were in attendance: the Schwier and Gäbler families, Anni Kleemann, Laasner, Brother Riedel, and Sister Domke. On this occasion, the members reported on their experiences in fleeing Forst and bore testimony to the way the Lord had led them through this difficult time and how each had had to take “his own path.” When they returned to Forst, the city was totally destroyed, including the meeting house. Most of the families had lost their homes.

The surviving Latter-day Saints of the Forst Branch headed west to Cottbus (ten miles) to join other LDS refugees at the Fritz Lehnig home.

The Gäbler family lived in Berge in the closest house to the left. (E. Gäbler)

The Gäbler family lived in Berge in the closest house to the left. (E. Gäbler)

By May 1945, Sister Schäler and her children had joined the LDS refugee colony in Cottbus. Georg Schäler had been compelled to stay and defend Forst. After the Soviets arrived, they destroyed his glasses, without which he was nearly blind. Fortunately, he was not detained and joined his family in Forst just days after the war ended. The family did not return to their Forst neighborhood again for another year, and when they did, there was nothing left of their apartment building.

All that remains of the Gäbler home in Berge today is the foundation. All usable building materials in Berge after the war were taken for the reconstruction of Warsaw. (R. Minert, 2008)

All that remains of the Gäbler home in Berge today is the foundation. All usable building materials in Berge after the war were taken for the reconstruction of Warsaw. (R. Minert, 2008)

When Bruno Gäbler took his family back to Forst, they found that the Polish (to whom the area east of the Neisse River now belonged) had burned their house down. With no place to stay, they were forced to leave. They crossed the river to the German side and began life anew in the southwest Forst suburb of Nossdorf.

In the summer of 1945, Charlotte Schulze prayed for a way to get back to Berge to rescue her Church books from the family apartment. She managed to find a work detail for the Polish across the river and was able to carefully sneak into her home. She found “amid a terrible mess” some scriptures and hymnals but not what she sought most—“the history of the Forst Branch that I had so carefully and lovingly compiled. I was in the house again on three occasions and was very saddened by this loss.”[15]

At war’s end, Eberhard Gäbler’s unit was officially taken prisoner by British troops in northern Germany. They were classified as POWs but lived in a barn and were allowed to move about in the area a bit. Later, when the English were looking for an aide for a military judge, Eberhard volunteered to do that job.

In September 1945, Eberhard was released as a British POW. After working on a nearby farm until November, he sneaked across the border into the Soviet occupation zone and headed home to Forst. The trip took five days. When he got off the train in Forst, he was delighted to run into his sister who had come to pick up a friend.

In early 1946, Günther was shipped to the British Isles, where he worked first in Scotland and then in southern England. In 1947, he was released as a POW and returned to Germany and his hometown of Forst. As a priest in the Aaronic Priesthood, Günther had been isolated from the Church and other Latter-day Saints for five years. However, he lost no time in rejoining the Saints:

When I went home, I attended the meetings again right away. There were most of the people I knew because the branch slowly started to come together again. I also received a calling very soon after my return because every person was needed.

Looking back on the branch and its members during the war, Doris Schäler offered the following comments:

We boosted each other’s faith and expectations although things looked horrible all around us. But knowing that there are others who also suffer and on whom you can rely for support and who believe in the same source of comfort really helped us through hard times—particularly in 1944 and 1945. Without having other Saints and the meetings and the prayers and sharing everything we had, . . . we would not have been so strong.

Relatively few members of the Forst Branch died during the war and enough of them returned to the city to begin Church meetings and activities anew in the summer of 1945.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Forst Branch did not survive World War II:

Ida Klara Bredsch b. Hennersdorf, Sorau, Brandenburg, Preussen 29 Aug 1861; dau. of Eduard Bredsch and Amalia Lipscher; bp. 23 Aug 1924; m. —— Paul; d. stroke 9 Mar 1945 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1410–11; IGI)

Günter Wolfgang Dommaschk b. Forst, Brandenburg, Preussen 24 Dec 1925; son of Willy Mensel and Dora Gertrud Erna Dommaschk; blessed Forst 21 Mar 1926; bp. 26 Jul 1941; k. in battle Stuhlweißenburg, Hungary 23 or 25 Jan 1945 (E. Gäbler; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Karl Falkner b. Bostenhofen, Nürnberg, Mittelfranken, Bayern 14 Jun 1885; son of Paul Heinrich Falkner and Anna Katharina Lauterbach; bp. 14 Nov 1925; m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 1 Dec 1907, Ida Klara Taubert; 5 children; 2m. Chemnitz 11 Sep 1926, Lina Ella Tierlich; 3 children; 3m. Helene Mehnert; d. Chemnitz 22 Dec 1942 or 1944 (FHL Microfilm 25764, 1930 Census; IGI; AF)

Auguste Pauline Lerche b. Reichersdorf, Brandenburg, Preussen 14 May 1864; dau. of —— Lerche and Maria Elisabeth Lorisch; bp. 25 Jul 1921; m. Forst, Brandenburg, Preussen 1 Dec 1888, Johann Karl August Schimmack; 1 child; d. Forst 19 Mar 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 15, 13 Apr 1941, 60; FHL Microfilm 245259, 1935 Census; IGI)

Max Paul Schulze b. Forst, Brandenburg, Preussen 4 Nov 1895; son of Johann Schulze and Marie Johanna Koinzer; bp. Forst 27 Sep 1923; conf. Forst 27 Sep 1923; m. Forst 18 Sep 1920, Frieda Anna Marie Stahn; 3 children; Volkssturm; MIA 1945; declared dead 31 Jul 1949 (E. Gäbler; www.volksbund.de; IGI; AF)

Lina Ella Tierlich b. Gablenz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Feb 1900; dau. of Heinrich Franz Tierlich and Lina Anna Taubert; bp. 17 Mar 1926; m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Sep 1926, Karl Falkner; 3 children; d. Chemnitz 7 Jan 1944 (FHL Microfilm 25764, 1930 Census; IGI; AF)

Paul Friedrich Helmut Wirth b. Forst, Brandenburg, Preussen 18 Oct 1916; son of August Bruno Wirth and Therese Berta Hulda Wandtke; bp. Forst 21 or 31 Jul 1926; conf. Forst 21 Jul 1926; m. 24 Nov 1939, Gerda Weise; corporal; k. in battle Western Front 18 Jun 1940; bur. Andilly, France (E. Gäbler; www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Helga Schäler Price, interview by the author, Highland, Utah, February 17, 2006.

[3] Eberhard Gäbler, interview by the author in German, Forst, Germany, June 7, 2007; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 22, East German Mission History.

[5] Ibid., no. 47.

[6] Irmgard Helga Gäbler Henkel, interview by Jennifer Heckmann in German, Bretzfeld, Germany, August 17, 2006; unless otherwise noted, transcript or audio version of interview in author’s collection.

[7] Doris Charlotte Schäler Shapardanis, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann, March 5, 2008.

[8] “Before we went to Africa, they looked for three people who wanted to go. We [three friends] did not want to be separated because we were used to each other as companions and got along well. So we volunteered and went to Africa. Everybody else in our group went to Stalingrad [Russia]. That was a blessing. Heavenly Father had his hand in things.” Günther Gäbler, interview by the author in German, Forst, Germany, June 7, 2007.

[9] Horst Schäler, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, May 8, 2008.

[10] Doris Charlotte Schäler Shapardanis, “World War II Experiences of the Schaeler Family and Members of the Forst Branch” (unpublished), 7; private collection.

[11] Charlotte Schulze Riedel, report (unpublished), 1; private collection; trans. the author.

[12] Ibid., 5–6.

[13] Ibid., 8.

[14] Eberhard Gäbler, Gemeinde Forst Vor 50 Jahren—1945, in Der junge Zweig (unpublished history, 1995); private collection.

[15] Riedel, report, B2.