The East German Mission

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 23-38.

Mission and District conferences (such as this one in Schneidemuhl) often attracted more than a thousand members and friends during the first few years of the war. (W. Kindt)

Mission and District conferences (such as this one in Schneidemuhl) often attracted more than a thousand members and friends during the first few years of the war. (W. Kindt)

The home of the East German Mission was a stately villa on Händelallee 6. Across the street to the south was the famous Tiergarten—Berlin’s answer to New York’s Central Park. The Siegessäule (Victory Tower), one of the famous landmarks of Germany’s capital city, was just two hundred yards to the southeast. From his office on the main floor, Alfred C. Rees of Salt Lake City presided over the East German Mission. In the summer of 1939, the mission included all of Germany east of the Elbe River and portions of Saxony to the southeast of the River (see map). Officially founded on January 1, 1937, the mission had a population of 7,601 members in early 1939 and was one of the largest missions (by population) in the world at the time.[1]

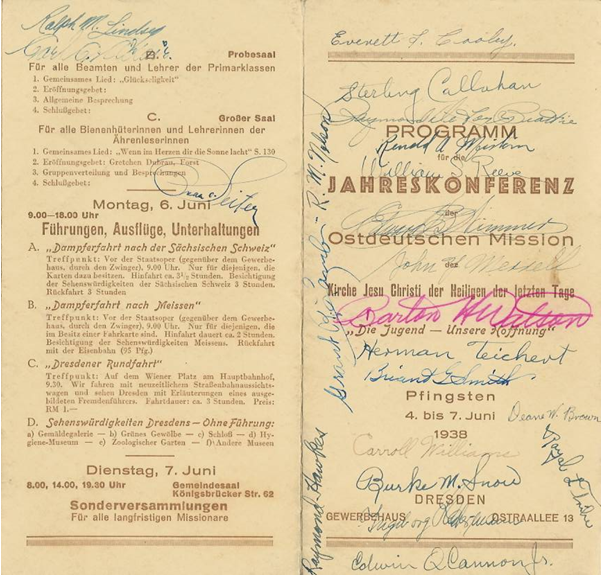

The decade of the 1930s was a time of resurgence in the East German Mission. The wave of emigration of Latter-day Saints from Germany following World War I had diminished many branches and even led to the demise of some. However, Hitler’s Third Reich produced a revitalized economy by 1935, and Germany had become a fine place to live—at least for the great majority of Germans. The work of about seventy full-time LDS missionaries was supported by loyal members. Convert baptisms were common, and most meeting facilities were in excellent condition.[2] In 1938, a huge four-day conference was held in Dresden; the printed conference program indicates that all Church programs and organizations existed and were functioning very well among the thirteen districts and seventy-two branches of the mission. According to the mission secretary, “Approximately a thousand saints and friends from all over Eastern Germany came together and made the conference a wonderful success.”[3] From that standpoint, it was an excellent time to be a Latter-day Saint in Germany.

The territory of the East German Mission when World War II began.

The territory of the East German Mission when World War II began.

Perhaps the most public success achieved by President Rees during his seventeen-month tenure was the publication of a lengthy article in the Berlin edition of the Völkischer Beobachter (People’s Observer), the official newspaper of the Nazi Party. Under the title “In the Land of the Mormons,” the article emphasized certain perceived similarities of the Church and Hitler’s new Germany.[4] For example, whereas the LDS Church had suffered persecution at the hands of the residents of Ohio, Missouri, and Illinois, Germans had been forced to suffer under the humiliating stipulations of the Treaty of Versailles that ended World War I. The appearance of the article and the invitation to President Rees to write it offers some evidence that the Church was initially not at odds with the Third Reich.

Program from the 1938 Dresden mission conference. (W. Andersen)

Program from the 1938 Dresden mission conference. (W. Andersen)

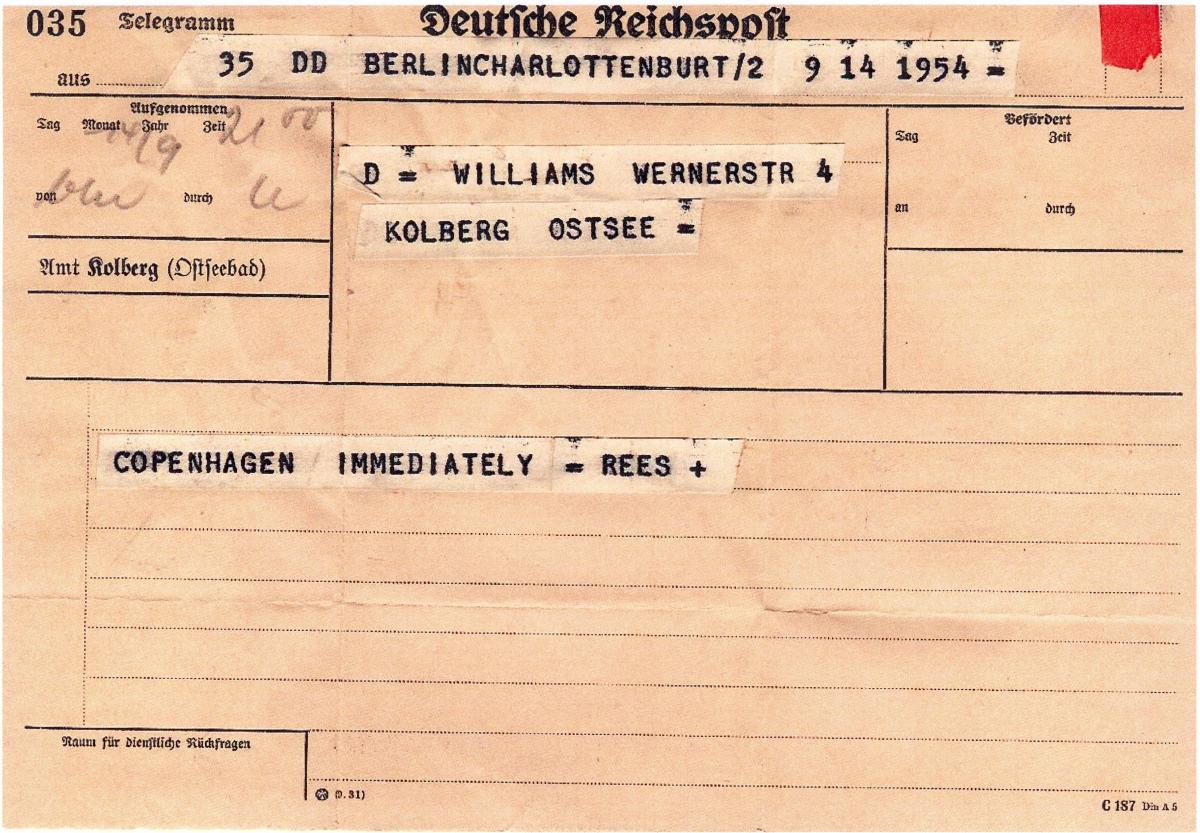

However, the growing tension in European politics in the late 1930s began to be felt throughout the mission. The German government had instituted universal military conscription in 1935 and more and more male members of the Church were seen in uniform. The German army marched into the demilitarized Rhineland in 1936 and was involved soon thereafter in the Spanish Civil War. In March 1938, Germany annexed Austria. On September 14 of that year, rumblings of war caused concern among Church leaders in Salt Lake City, and they ordered an evacuation of the American missionaries from the two German missions. Those in the East German Mission headed quickly to Copenhagen, Denmark. Mission records included this statement: “During the absence of the Elders from their fields of labor, local members were called upon to take over their offices, which they did with integrity and earnestness. The call came, then they answered.”[5] When it turned out that the German occupation of the Sudeten territory in Czechoslovakia earlier that month did not lead to armed conflict, the missionaries of the East German Mission left Copenhagen and returned to their assignments by October 6.[6] During the 1930s, the greatest problem caused by the German government for the Church was the dissolution of the Boy Scouts. Under the Nazi concept of Gleichschaltung (bringing all organizations into line with Party goals), Latter-day Saint branches were required to discontinue all Boy Scout troops so that the boys could be inducted into the Hitlerjugend (Hitler Youth). This development was a great disappointment to the young men of the Church.[7]

Elders Williams and Andersen received this telegram in Kolberg on September 14, 1938. (W. Andersen)

Elders Williams and Andersen received this telegram in Kolberg on September 14, 1938. (W. Andersen)

On Friday, September 30, 1938, a new meeting schedule became effective in the East German Mission. Named the “Weekly Hour Meeting,” this plan stipulated that the Relief Society, the MIA, the Genealogy Association, the Gleaner and Beehive girls, and the priesthood were to meet once a week simultaneously and at the same place and then repair to their respective classes, where a special committee directed the program.[8] It is not known whether this scheduling change was suggested due to the lack of missionary support in the branches.

| East German Mission [9] | 1939 | 1940 |

| Elders | 385 | 419 |

| Priests | 191 | 194 |

| Teachers | 237 | 255 |

| Deacons | 429 | 429 |

| Other Adult Males | 1,281 | 1,228 |

| Adult Females | 4,385 | 4,328 |

| Male Children | 372 | 392 |

| Female Children | 347 | 373 |

| Total | 7,627 | 7,618 |

With Germany preparing for war in 1938, security was high, and foreigners such as American missionaries were in a position to see things that might be of interest to politicians and military experts in other countries. Adventuresome missionaries at times photographed military scenes, apparently unaware of ways in which their actions could be construed. On May 18, 1939, President Rees issued the following warning:

We have again received official notice that taking photographs is a dangerous practice on the part of foreigners. We have already been asked to keep our kodaks in our trunks. This is again to advise you that I shall not be responsible for what may follow any breach or disregard of this request. I hope our obedience will be immediate, willing and lasting.[10]

He also instructed his missionaries to avoid all trade in foreign currencies, such as purchasing Polish zloty with German marks.

The growth of the German military in the two years before the war required the induction of many members of the Church from all over Germany. It is possible that some members were not enthusiastic about the presence of army, navy, and air force uniforms in the meetings, which may have led to this instruction from President Rees on April 8, 1939:

If the organizations to which our young or older brethren belong do not require that they appear Sundays in uniform, they should be asked to dress in civilian clothes when coming to meeting and participating in ordinances. If, however, they are required to wear [the] uniform, they should not be denied the right or the privilege to participate in any of the activities of the priesthood to which they belong.[11]

In May 1939, the East German Mission held its last missionwide conference before the war. The theme was “The Trumpet Sounds for the Last Time.” Such phrases were already common among the members of a church whose very name suggested that the return of the Savior Jesus Christ was imminent. However, it seemed to Berlin district president Richard Ranglack that hardly any of the members understood the deeper meaning of that motto.[12] Perhaps he believed that some of the calamities prophesied for the latter days were soon to be experienced in Germany.

On July 31, 19 39, Alfred C. Rees was officially released as the president of the mission. His successor was Thomas E. McKay, then serving as the president of the Swiss Mission in Basel. President McKay’s instructions were to move to Berlin to take charge of the East German Mission, while temporarily remaining also as the president of the Swiss Mission.[13] With appropriate enthusiasm, Alfred C. Rees informed his missionaries of the change in leadership, “It is a source of deep satisfaction to know that those who stand at the head of the church, and who speak in the name of the Lord, have chosen President Thomas E. McKay to preside over this mission.”[14]

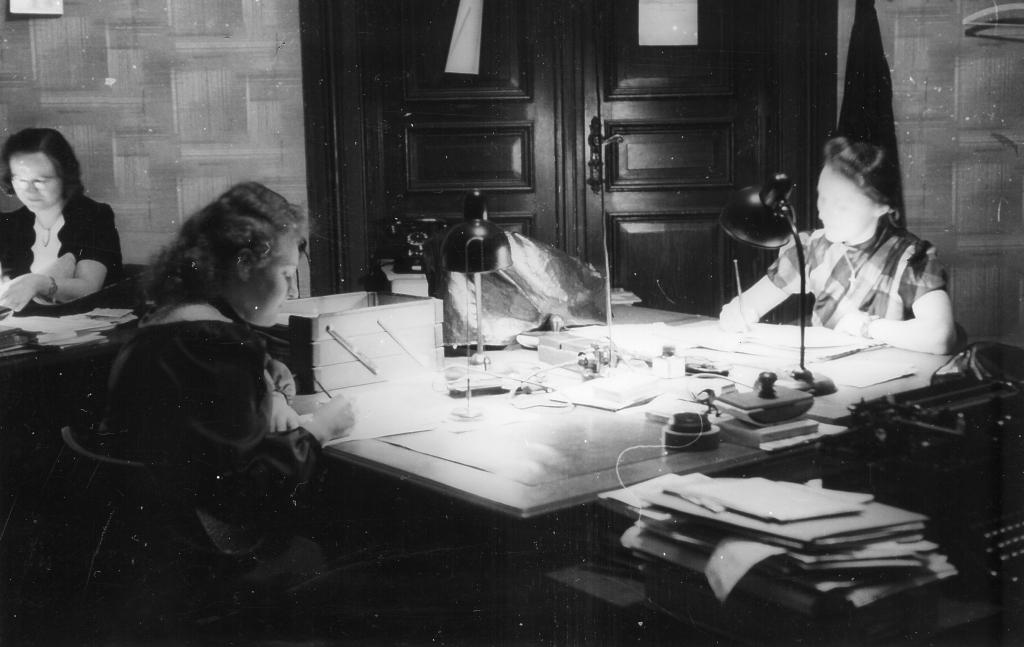

The mission leaders and office staff in 1940. From left: Missionaries Erika Fassmann, Johanna Berger, and Ilse Reimer. Behind them: first counselor Richard Ranglack, mission supervisor Herbert Klopfer, and second counselor Paul Langheinrich.

The mission leaders and office staff in 1940. From left: Missionaries Erika Fassmann, Johanna Berger, and Ilse Reimer. Behind them: first counselor Richard Ranglack, mission supervisor Herbert Klopfer, and second counselor Paul Langheinrich.

The tenure of President McKay in the East German Mission was not a long one because on Friday, August 25, 1939, a telegram arrived from Elder Joseph Fielding Smith, who was touring Germany and was in Hanover at the time. All foreign missionaries serving in Germany and Austria were to leave immediately for the Netherlands or Denmark.[15] The next day, Wynn S. Andersen, a missionary from Brigham City, Utah, and a member of the mission office staff, sent a telegram to each pair of missionaries with the appropriate instructions.[16]

“I was in the mission office when the evacuation message came in,” recalled Richard Ranglack. American missionaries were released as branch leaders and worthy German brethren were set apart. “I will never forget those days.” His story continued:

Thomas E. McKay was so worried about the Church in Germany. [He] transferred the responsibility for the East German Mission to Elder Herbert Klopfer, then the [Church’s] interpreter and translator, with Elder Richard Ranglack as first counselor and Elder Paul Langheinrich as second counselor.[17]

After all of the missionaries were evacuated, President McKay returned to Basel.[18] Before leaving the Berlin office, he had designated Herbert Klopfer as the mission supervisor. Brother Klopfer’s title and duties were described in detail in a letter he received from President McKay on February 13, 1940. The central message was as follows: “All communications to the Presiding brethren and saints in the mission should go out over your name as mission supervisor.” (The German term was Missionsleiter.) He was to be paid a full-time salary, select two assistants, advise President McKay of major decisions, maintain contact with the leaders of the West German and Swiss Missions, and send a weekly letter to President McKay.[19]

To underscore Brother Klopfer’s appointment as the mission supervisor, President McKay appended a letter to be sent to the Saints in the mission: “To notify them of your call, your responsibility, and your authority. They will then know that you are acting in complete co-ordination with the authorities here and that what you do and say is official.”[20]

Born in Werdau, Saxony, in 1911, Klopfer had served a full-time mission in eastern Germany and was barely twenty-eight years old when called to lead the mission. A faithful servant of the Lord, he had served as a full-time employee of the Church in foreign language correspondence and translation since 1933. In this capacity, he moved to Berlin from his hometown. He had excellent English skills (a result of living and working with American missionaries) and had interpreted for visiting General Authorities of the Church. This he did so well that people would ask him how long he had been in Germany; they thought he was an American who spoke better English than German.[21]

As mentioned, Richard Ranglack and Paul Langheinrich were chosen as his counselors. Both were experienced Church leaders and both proved equally dedicated in their service during and after the war.

The mission home on Händelallee 6 was a stately structure of four stories, sandwiched between similar structures. Much of its space was rented out by the Church.[22] Brother Klopfer moved into the home in September 1939 and lived on the main floor with his wife, Erna, and two sons, Wolfgang (Herbert) and Rüdiger.[23] The mission office had office space on the same floor. The sister missionaries (all native Germans) lived on the top floor and male missionaries were housed in the basement. Other (non-LDS) families lived in other apartments. According to young Wolfgang Herbert Klopfer: “From the living room there was a balcony that looked out to the front of the house, right into the Tiergarten. My friend and I used to jump off of it with umbrellas as mock parachutes. It was fun, but my friend broke his legs doing that.”[24]

One of the last men serving full time in the East German Mission when the war began on September 1, 1939, was Richard Deus of Breslau (now Wrocław, Poland). Called as a traveling elder in March of that year, the husband and father of three was released in the spring of 1941 when he was drafted into the German army. Erika Fassmann of Zwickau was called as a missionary in 1940 and was one of five young women who served for at least two years during the war. The others were Edith Birth, Irmgard Gottschalk, Johanna Berger, and Ilse Reimer.

As Sister Fassmann recalled, “We did everything for the mission, because the brethren were all gone. We traveled to the district conferences and taught the sisters of the Relief Society, young women, and Primary. We were not allowed to tract, so we always worked in the office when we were in Berlin.”[25] Sister Fassmann remembered traveling as far as Königsberg, Danzig, Breslau, and Dresden to attend and speak at district conferences. Despite the confusion of wartime railroad schedules and trains that often seemed to have room for troops only, she was somehow always able to secure railway tickets.

One of the last things Thomas E. McKay did as the president of the East German Mission was to extend a mission call. On January 1, 1940, he sent a letter to Ilse Reimer of the Kolberg Branch (Stettin District), asking her to come to Berlin in March. She accepted the call to work in the mission office at Händelallee, where she was to live with other sister missionaries.[26] By the time Sister Reimer arrived in Berlin, President McKay had returned to Basel, Switzerland.

Edith Gerda Birth recalled the following about her service in the mission office:

The greatest need was for lesson material for all the organizations. In my diary I wrote about the many manuals we had to type and to print, the manuals for the Sunday school and Primary, Genealogy, gospel doctrine class, the monthly Sonntagsgruss, etc. We had a little printing press in one room of the office, which was always in use. . . . All these printings we had to pack and take to the post office in a little hand wagon.[27]

Under Brother Klopfer’s capable leadership, meetings continued with district presidents and priesthood groups, and district conferences were held for the general membership. Fulfilling his calling became a personal challenge to Brother Klopfer when he was drafted into the army in 1940. Fortunately, he was stationed in Fürstenwalde (about forty miles east of Berlin) for the next three years. As a paymaster, he was able to take the train home to see his family on weekends and to travel to Church conferences in other cities. His counselors also visited him several times in Fürstenwalde to transact mission business and receive instructions.[28] Elder Klopfer wrote articles for Church publications and received visits from his wife and sons while in Fürstenwalde. On several occasions Sister Klopfer in the mission office transferred messages from her husband to Thomas E. McKay in Salt Lake City.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, mutual declarations of war were issued by several nations. Because Japan and Germany had commenced a military alliance when the former declared war on the United States, Germany was required to follow suit. When that occurred, all communications between the Church leadership in Salt Lake City and the East German Mission leaders in Berlin were discontinued. The Saints in Germany were on their own.[29] During the absence of Brother Klopfer, counselors Richard Ranglack and Paul Langheinrich redoubled their efforts to maintain contact with district and branch leaders. Brother Klopfer was sometimes able to use an office telephone from his post in nearby Fürstenwalde, but otherwise wrote weekly letters to his counselors with advice and instructions.[30] Periodic meetings were held in Berlin with the district presidents, who traveled by rail from as far away as two hundred miles.

Leaders of the East German Mission met in the office at Händelallee 6 in 1941 with the district presidents and the sister missionaries. Mission supervisor Herbert Klopfer and four of the thirteen district presidents lost their lives in the war.

The German invasion of Poland on September 1, 1939, initiated a war that eventually meant the deaths of tens of millions of people. Latter-day Saints in Germany were not spared. The first known death was that of Willy Klappert of the Frankfurt am Main Branch in the West German Mission, who died on September 2.[31] For many years, issues of the Church publications in Germany had listed notices of members who died—civilians and soldiers alike. Der Stern (established in 1869) served both German missions, but its publication was interrupted in 1942. Thereafter, the mission office in Berlin issued first the Sonntagsgruss (Sunday Greetings), then the Sonntagsblatt (Sunday News). Over time, the quality of the publications suffered due to wartime shortages: only coarse paper was available, and photographs could not be included.

In the absence of Herbert Klopfer, Brother Ranglack represented the Church on several occasions in investigations conducted in the office of the Gestapo (the secret state police) in Berlin:

Heavenly Father put the words in my mouth so that I was able to answer questions concerning our church. I was especially asked about our tenth article of faith, our position towards the N.S.D.A.P. [Nazi Party], membership in the party, Hitler youth, bearers of the knight’s cross, [and] more. The singing of songs that contained the word “Zion” was prohibited. I was also asked concerning our meeting halls, conference mottos, the gathering of Israel, the American Church, our views about the war. I had [the] responsibility [to see] that all the sermons given were of [a] purely religious nature.[32]

In early 1941, the Sonntagsblatt featured the membership populations for the East German Mission (see introduction). Accompanying comments indicated that 101 children were blessed in 1940, 44 children of record baptized, 45 adults baptized, 73 members died, and 121 had married.[33]

“It was our intention to keep the work of the Lord alive in Germany, to strengthen the faith of the members, and to see to it that the brethren remained active,” reported Brother Ranglack. “We held district conferences in each district twice a year from 1940 through 1944 . . . and were able to travel all over the mission.” He and Paul Langheinrich even traveled once to Czechoslovakia, visiting with the Saints in Prague and Brünn for four days each.[34]

Hard at work in the mission office (from left): Johanna Berger, Erika Fassmann, and Ilse Reimer. (I. Reimer Ebert)

Hard at work in the mission office (from left): Johanna Berger, Erika Fassmann, and Ilse Reimer. (I. Reimer Ebert)

Sister Ilse Reimer provided the following description of a day in the life of the sister missionaries in the mission home during this time:

Erika [Fassmann] and I usually got up at 6:00 a.m. and enjoyed the fresh morning air of the Tiergarten. When Erika slept in a bit, I practiced handstands in another room. I was pretty good at that, even though I had not been on the school gymnastics team. Then we had a simple breakfast. From seven to eight we were to study the standard works of the Church. We worked in the mission office from 8:00 a.m. until 6:00 p.m., with a one-hour break for lunch. . . . Every missionary had her specific duties. Sometimes several of us worked on the same project. My assignment was to analyze the monthly statistical reports submitted by the district presidents.[35]

“There were highlights for us missionaries when we visited with the brethren at the district conferences, which were still held,” wrote Edith Birth. “All the members looked forward to the district conferences. These conferences strengthened out testimony and kept us together and gave us support to stand up for the teachings of Jesus Christ.”[36]

Ilse Reimer also enjoyed the district conferences, but speaking to large audiences was not one of her favorite assignments. Her talks were to be twenty minutes in length. The only way she felt confident in giving such long talks was to memorize each one in its entirety.[37]

A mission conference was held in Berlin on Sunday, June 1, 1941. That evening, Karl Göckeritz, president of the Chemnitz District, noted in his diary that the conference was held in the Lehrervereinshaus (teachers’ union hall) in downtown Berlin and that 1,400 members and friends were in attendance.[38] Representatives of the West German Mission also came from Frankfurt am Main to participate in the conference. Christian Heck was the first counselor to West German mission supervisor Friedrich Biehl and Anton Huck the second counselor. Elder Biehl was on active duty in the army at that time.[39]

Missionaries Johanna Berger (left) and Ilse Reimer in the garden on the rooftop of the mission home. (I. Reimer Ebert)

Missionaries Johanna Berger (left) and Ilse Reimer in the garden on the rooftop of the mission home. (I. Reimer Ebert)

Missionaries Johanna Berger (left) and Ilse Reimer in the garden on the rooftop of the mission home. (I. Reimer Ebert)

In February 1943, Herbert Klopfer wrote a letter to his brethren in the mission leadership detailing their responsibilities in his absence. The letter was written from the mission office and began thus: “During the period of my prolonged absence and due to the hindrances caused thereby for the leadership of the mission, I would ask that my elders called to serve as mission leaders observe the following directives.” He then provided instructions in twelve specific topics, such as historical reports, communications with district and branch leaders, publications, finances, and relations with the West German Mission. It is not impossible that Elder Klopfer had a premonition that he would soon no longer be able to carry out his duties as mission supervisor.[40]

On February 25, 1943, Richard Ranglack of the mission leadership issued instructions to all units that no copies of the Sonntagsgruss should be sent to military personnel. It read in part, “Due to increased restrictions in the use of paper and by order of the Army High Command, we have received the message that no religious literature may be sent to soldiers in the field.”[41] Brother Ranglack requested that branch leaders and families alike give strict heed to this order. Despite the restrictions on printing, mission leaders were successful in finding private printing companies to produce German-language hymnbooks, portions of Jesus the Christ, and several copies of the Pearl of Great Price, as well as small tracts.[42]

After twenty-five months of service, Sister Ilse Reimer was released from her mission in April 1942. She later wrote, “I would very much have liked to stay longer on my mission. . . . It was one of the most beautiful times of my life.”[43] Engaged to marry Fritz Ebert, an elder in the Stettin Branch, she compiled her final reports then boarded the train for the trip home to Kolberg (Stettin District).

As Germany’s capital city came under increased attack from the enemy (the U.S. Army Air Corps by day and the Royal Air Force by night), Brother Klopfer moved his family to his hometown of Werdau in early 1943, where they lived with both sets of grandparents. That fall, the East German Mission home at Händelallee fell victim to the attacks. On the evening of November 21, 1943, Erika Fassmann was the only missionary in the building. She remembers:

On this evening I was totally alone in the office. I again disregarded the alarm (we missionaries usually did that because we believed the Lord would save us—the brethren scolded us more than once for doing so). Then I heard the bombers coming and they apparently were heading right for [the neighborhood of] Händelallee. Suddenly the huge wood [front] doors were blown into the building. I hid in the kitchen and prayed for protection. Then I wondered where I could seek refuge. In the office we had a huge table on which genealogical papers—family group records—were stacked in tall piles. I told myself: “If the Lord protects anything at all, it will be these papers.” So, I dove underneath the table. Then when the bombs stopped, I grabbed all of the papers and ran out of the building. All of the buildings around me were on fire. The moon was red and the sky on fire and I thought it was the end of the world.

Sister Fassmann recalls feeling relieved that the mission home had escaped destruction. However, the next morning, Richard Ranglack and Paul Langheinrich insisted that they evacuate the building. They spent all day moving mission property to the Langheinrich home at Rathenowerstrasse 52, about one mile to the north. By evening, only the personal possessions of the sister missionaries and some of the property left behind by the Klopfers were still in the building. The inspiration received by the brethren was right; the bombers returned that evening, and the mission home was completely destroyed.

Missionary Johanna Berger in front of the mission home (I. Reimer Ebert). All of the buildings behind her were destroyed in the war, as can be seen in the 2007 photograph below . (J. Larsen)

Young Wolfgang (Herbert) Klopfer recalls that his father was on furlough at the time. He had picked up his wife in Werdau and from there traveled to the mission home late on November 22. However, they had forgotten the key to the mission office and went on to the home of Brother Ranglack to spend the night. Had they remembered the key, they may have sought shelter in the basement of the building when the bombs fell the second time. Sister Klopfer told her son that she and her husband later visited the site and only the walls were standing. In the ruins they found the office safe with the tithing funds; the coins had melted from the heat of the fire and flowed out of the safe to form a small puddle of metal. The only item recovered from the ruins was a small teapot with its lid. Just after the Klopfers left the ruins, several delayed-action bombs exploded and leveled the surviving wall remnants. Again they narrowly missed being killed.[44]

The discouraging scene on November 23, 1943, was later described by Richard Ranglack: “The next morning we stood before the burned-out building. The feelings that came over us naturally gave way to tears. Now we had to start over. Our energy and courage would come from a higher source.”[45]

The ruins of the mission home at Händelallee 6 as shown in an Allied reconnaissance photograph of March 1945 (circled at upper left). To the right is the Victory Tower, one of Berlin’s most famous landmarks.

The ruins of the mission home at Händelallee 6 as shown in an Allied reconnaissance photograph of March 1945 (circled at upper left). To the right is the Victory Tower, one of Berlin’s most famous landmarks.

From November 1943 until after the war, the mission office was housed in the apartment of the building in which the Langheinrich family lived. One by one, more apartments in the five-story building were vacated and Brother Langheinrich was quick to appropriate them for the missionaries and an increasing number of LDS refugees. They arrived from points as close as neighborhoods in Berlin and as far away as Königsberg, East Prussia. At the conclusion of the war, there were at least forty members of the Church living in the building.[46]

Junior Officer (Sergeant) Herbert Klopfer, the supervisor of the East German Mission, visited his family for the last time while on furlough in November 1943. Soon after, he was transferred to Denmark where he had a remarkable experience on the Sunday before Christmas. A young girl in the Esbjerg Branch later wrote the following account to Sister Klopfer:

Last night I visited the branch. There was a German. And even though we hated all Germans, we learned to love this man. He spoke to the congregation in English, because we could not stand to listen to German, and William Orum Petersen from Copenhagen, who was present, translated. Your husband related how only a month ago he lost everything he had, and the mission home had been destroyed, but that he was thankful that his wife and children were in safety. He then gave testimony of the truthfulness of the Church. It was wonderful to see a man in the uniform we hated, who spoke with so much love for us. He was happy to be among the Saints.[47]

The mission supervisor next served in France as a paymaster then was transferred to the Eastern Front. By then (the summer of 1944), the German army was retreating from the Soviet Union and was just a few miles from the fatherland. In early October, a letter arrived in the home of Erna Klopfer in Werdau informing her that her husband was missing in action. Part of the letter written by the company commander reads as follows:

It is my difficult responsibility to inform you that your husband, Junior Officer Herbert Klopfer, has been missing in action since July 22, 1944. . . . The division was surrounded on July 17. . . . A rescue mission was executed but was successful for only a few of the surrounded units. . . . I know how terrible it must be for you to not know the precise fate of your husband and I regret not being able to provide more details. Although we must consider the possibility that your husband was killed during the attempt to escape the encirclement, we can still hope that he will return home when the war is over.[48]

In Brother Klopfer’s absence, Max Jeske was called to serve as a counselor to Richard Ranglack, now the de facto mission supervisor. Eventually, it was learned that Brother Klopfer had perished in a squalid hospital near Kiev, Ukraine. His son, Herbert, explained how they learned what actually became of the mission supervisor:

Another soldier in his company made a conscious decision on the nineteenth of March, 1945, when he saw my father die; he made a note of the date and made a decision that if he were to make it out alive he would look up my mother and tell her that he was an eyewitness to my father’s passing. He didn’t know whether he was going to make it out, but in 1948, which is three years after the war ended, he was allowed to walk out of Ukraine to go home to his wife and on his way home he looked us up in Werdau and gave my mother the news that he was an eyewitness. That’s the first information we had received in five years as to what ever happened to our father.[49]

Without the report of this dedicated comrade, the death of Herbert Klopfer may have never been confirmed.

Brother Ranglack narrowly missed being drafted into the Berlin police force on February 3, 1945—one of the most difficult days of his life. Concerned about his Church responsibilities, he feigned an illness, and the military physician classified him as unfit for duty. That same day, his family’s apartment and the hotel where he worked were both destroyed in an air raid. Fortunately, he and his family were able to move into an apartment in the building where Paul Langheinrich lived.[50]

In March 1945, Paul Langheinrich allowed Erika Fassmann Müller to go home to her parents in Zwickau. (She had married Rudi Müller of Danzig five months earlier.) She had requested permission to participate in the celebration of her parents’ twenty-fifth wedding anniversary. She was not yet released as a missionary.

On April 21, 1945, the invading Russian army began to work its way through the streets of Berlin in an agonizing battle that eventually cost the lives of nearly 350,000 civilians and soldiers (German and Soviet).[51] As the enemy approached his neighborhood, Paul Langheinrich was already hosting about thirty members of the Church in his apartment house. In her diary, missionary Helga Meiszus Birth of the Tilsit Branch in East Prussia recorded the arrival of mothers and children from January through April. In summary, she made this pronouncement: “Rathenowerstrasse 52 has become the place of refuge for the Saints.”[52]

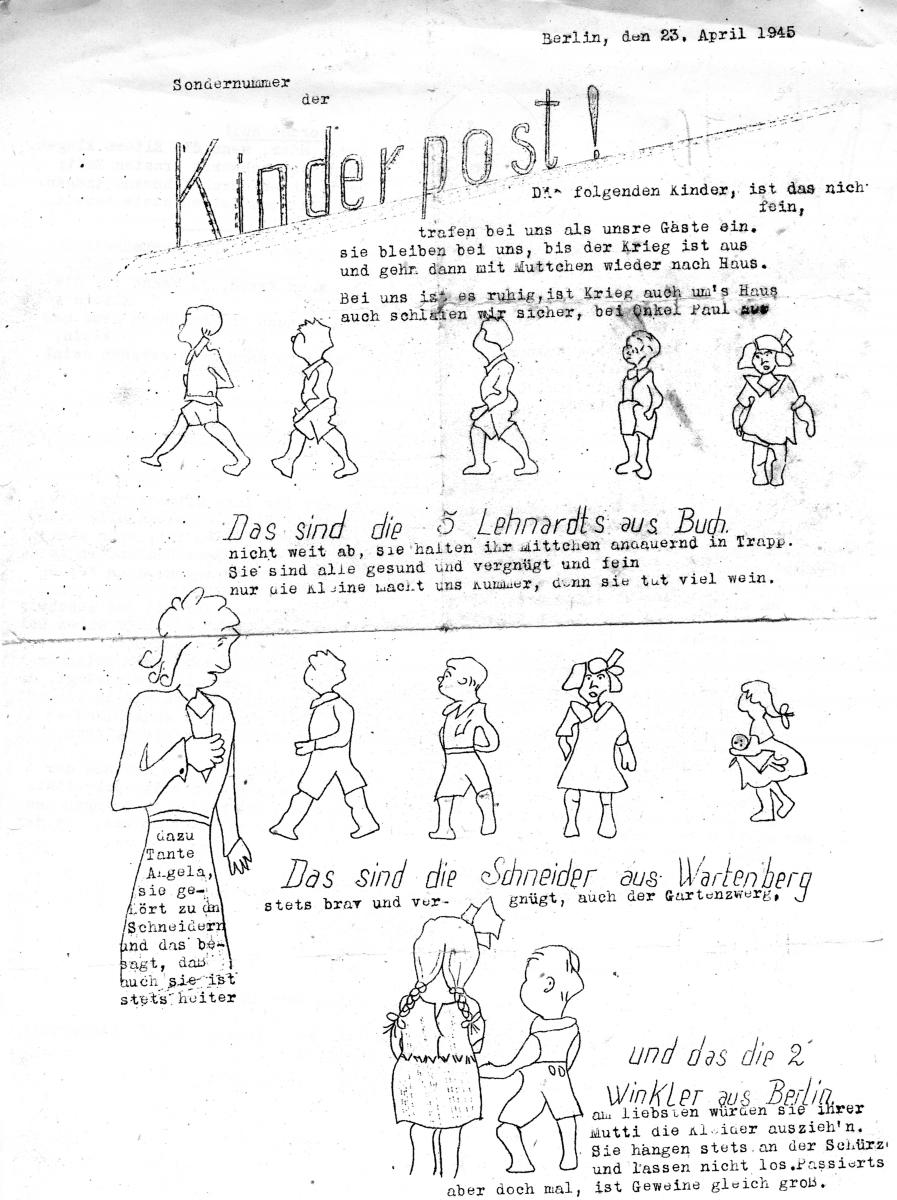

Paul Langheinrich was the editor of the Kinderpost. (R. Winkler Heidler)

Paul Langheinrich was the editor of the Kinderpost. (R. Winkler Heidler)

Despite the challenge of feeding and protecting the refugees, Paul Langheinrich devoted some time to the entertainment of the children. On April 25, 1945 (the day the Soviets completed their encirclement of Berlin), he used the mission mimeograph machine to reproduce under the title Kinderpost some fanciful poetry and art for the children of the Lehnardt, Schneider, and Winkler families living in the same building. One of his poems read,

Listen up! You children, when your parents complain in this very worrisome time, help them through your obedience to bear it well and always be ready to help. A child can bring sunshine into the home, sunshine for his parents, and the neighbors, young and old, will be gladdened as well.[53]

Brother Langheinrich concluded this edition of the Kinderpost with a reminder that the children should pray for their country, for the soldiers, and for all of the refugees who were suffering.

The final defensive bastion in Berlin was the eight-story antiaircraft Tower G that stood just north of the city’s famous zoo, barely one thousand yards from Händelallee 6. When Tower G surrendered, the battle for the Reich capital was over.[54]

The invaders reached the Langheinrich’s neighborhood on April 28, four days before the city surrendered and ten days before the war officially ended.[55] As the sound of enemy artillery fire became audible, Brother Langheinrich probably wondered how he could protect the members of his household—mostly women and children. The day before, about three miles to the south, Ingrid Bendler and her mother, members of the Schöneberg Branch in Central Berlin, had discovered an abandoned government warehouse full of food. The building had just been opened to the public and they joined other desperate civilians in taking whatever food they could carry. Ingrid felt the urge to deliver food to the Langheinrich home, despite her mother’s protests:

My bike was really loaded and it was hard to keep the balance. Never before had I gone through Berlin in this direction. Shooting was very heavy and I had no idea where the front lines were. I remember turning into a burning street. People would come out of there and ask where it was not burning; they were confused. Listening to that still small voice that I had heard before, I would go right into those burning streets, make a [correct] turn and was safe. I remember turning at the most unusual places and finding my way over broken bridges. To my great surprise I found the mission [Langheinrich] home real easy. . . . Had there not been a living testimony based on previous experiences and the knowledge that there is a God who guides and directs us and answers prayers—food would never have reached twenty-four hungry people [in the Langheinrich home] under enemy fire.[56]

With the city’s surrender, Berlin became a madhouse of unbridled terror, with Soviet troops committing unspeakable atrocities against the citizenry. No female was safe, and the Langheinrich home was just another target. On May 4, 1945, Brother Langheinrich relied on a political ruse and posted a sign by the door saying “American Church Office.” The ruse was successful in turning away marauding soldiers who respected the name of their ally in the war against fascism.[57] On at least one occasion, he stared down a Russian soldier who apparently wished to enter the building with evil intentions. Nobody living in the Langheinrich apartment house was molested.[58]

Roger Minert in 2007 at the door to the apartment building that housed the Langheinrich family, the mission office, and many LDS refugees at the end of World War II. (J. Larsen 2007)

Roger Minert in 2007 at the door to the apartment building that housed the Langheinrich family, the mission office, and many LDS refugees at the end of World War II. (J. Larsen 2007)

From the mission office, principally from one room on the floor where the Langheinrich family lived, Brothers Ranglack and Langheinrich administered the affairs of the mission. They were assisted by missionary Helga Meiszus Birth and several young women refugees, such as Renate Berger of Königsberg and Angela Patermann of the Berlin East Branch. The young women spent many hours proofreading genealogical documents that were to be forwarded to Salt Lake City. Eventually, they began recording the whereabouts of Saints who were bombed out of or evicted from their homes.

When it was too dangerous to walk to their place of meeting (the Moabit Branch rooms had survived), the residents of the Langheinrichs’ apartment house at Rathenowerstrasse 52 held Church meetings at home. Helga Meiszus Birth’s very detailed diary includes the names of persons who gave talks, taught lessons, and offered prayers. A general prayer circle was conducted each morning at 8:00 and each evening at 8:00.

On May 11, 1945—three days after Germany surrendered—the mission records indicate that Sister Angela Patermann of the Berlin East Branch was called as a missionary and assigned to work in the mission office.[59] The leadership of the East German Mission clearly did not miss a beat as they contemplated how best to continue the work of the Lord amid the desolation and confusion of conquered and occupied Germany. “We had three goals,” recalled Richard Ranglack, “to find the members who had been driven from their homes, . . . to call full-time missionaries, . . . and to find a larger facility for the mission home.”[60] By the end of the year 1945, all three goals had been totally or substantially achieved. Mission leaders calculated that at least four hundred members of the Church in the East German Mission had perished and hundreds more were missing.[61]

During the summer of 1945, the office of the East German Mission was established anew in a fine building in the southwest Berlin suburb of Dahlem.

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257; The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Der Stern, final no. for 1939–1941.

[2] The Church owned only one building in the mission—the modest chapel built for the branch in Selbongen, East Prussia, in 1929. The building still stands but ceased to serve the Church when the last members quit the town in 1973.

[3] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, nos. 26–27, East German Mission History.

[4] A copy of the newspaper, dated April 14, 1939, is in the possession of Clark Hillam, a veteran of the West Germany Mission. The most prominent feature of the article is a large photograph of the Salt Lake Temple.

[5] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 40.

[6] Ibid.; Wynn S. Andersen, interview by the author, Brigham City, Utah, October 19, 2006.

[7] During the years 1925 to 1934, the Church’s Der Stern magazine had often featured photographs of branch Boy Scout troops. The importance of the program to the Church in Germany, Austria, and Switzerland was apparent.

[8] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 40.

[9] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial,” 1938; Sonntagsblatt, no. 4, January 26, 1941 (unpublished); private collection.

[10] Alfred C. Rees to missionaries of East German Mission, letter, May 18, 1939, no. 7, trans. the author. Germany Berlin Mission, “Manuscript History and Historical Reports,” LR 2428 2. See the history of the Kreuz Branch, Schneidemühl District for the story of a specific event that may have precipitated this warning. See also Terry Montague’s Mine Angels Round About: Mormon Missionary Evacuation from West Germany 1939 for a similar problem that occurred in Saarbrücken ([n.p.: Roylance, 1989], 6).

[11] Alfred C. Rees to missionaries of East German Mission, letter, April 8, 1939, no. 5, trans. the author. Germany Berlin Mission, “Manuscript History and Historical Reports,” LR 2428 2.

[12] Richard Ranglack, autobiography (unpublished), 1; private collection. He does not claim to have understood it himself.

[13] Thomas E. McKay to missionaries of East German Mission, letter, August 17, 1939, no. 12, trans. the author. Germany Berlin Mission, “Manuscript History and Historical Reports,” LR 2428 2.

[14] Ibid. August 15, 1939, no. 11.

[15] Montague, Mine Angels Round About, 25–26. Church leadership in Salt Lake City called Hugh B. Brown in London and requested that he call the West German Mission office in Frankfurt. Mission secretary Elder John R. Barnes contacted President Wood and Elder Smith in Hannover with the news. They flew to Frankfurt immediately and instructed the mission staff to contact all missionaries with the evacuation order on August 25. Apparently, Elder Smith contacted President McKay with the same message at the same time.

[16] Wynn S. Andersen, interview. Because he sent the message, Andersen does not have a copy of the telegram. However, he has a copy of a similar message sent in September 1938, when the missionaries were evacuated the first time. They returned to Germany from Denmark in October 1938.

[17] Richard Ranglack, autobiography (unpublished); private collection.

[18] Thomas E. McKay left Berlin in December 1939 and returned to Switzerland. From there he left for the United States in April 1940 (Wolfgang [Herbert] Klopfer, memoirs [unpublished]; private collection; Douglas F. Tobler, interview by the author, Lindon, Utah, November 5, 2007).

[19] Thomas E. McKay to Herbert Klopfer, February 13, 1940. East German Mission History, CR 27, 140. Church History Library.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Herbert Klopfer, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, November 3, 2006.

[22] See map of downtown Berlin.

[23] Wolfgang officially changed his first name to Herbert after immigrating to the United States (Wolfgang [Herbert] Klopfer, memoirs).

[24] Ibid.

[25] Erika Fassmann Mueller, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, February 3, 2006.

[26] Ilse Reimer Ebert, autobiography (unpublished), 16–17; trans. the author; private collection.

[27] Edith Gerda Birth Rohloff, “Life Is a Gift from God” (unpublished history, ca. 2003), 20; private collection.

[28] Richard Ranglack, autobiography (unpublished), 2; private collection.

[29] The same was true with the office of the West German Mission in Frankfurt am Main.

[30] As reported by his son Wolfgang (Herbert) Klopfer, memoirs.

[31] Frankfurt-Main Branch, member records, FHL microfilm no. 68791, no. 298 (Book I), Family History Library.

[32] Ranglack, “Bericht” (unpublished history); private collection.

[33] Sonntagsblatt, no. 4, January 26, 1941; private collection.

[34] Ranglack, autobiography, 2. The office of the Czechoslovakian Mission was also closed prior to the war and the few Saints there had no leadership at all. The city of Brünn is now call Brno.

[35] Ilse Reimer Ebert, 17.

[36] Edith Gerda Birth Rohloff, autobiography (unpublished), 21; private collection.

[37] Ilse Reimer Ebert, 18.

[38] Karl Göckeritz, diary, 1909–1943; trans. the author; private collection.

[39] Mission supervisor Friedrich Biehl was killed in the Soviet Union in March 1943 and his successor, Christian Heck, was killed in South Germany in April 1945. Anton Huck was the supervisor of the West German Mission at the end of the war.

[40] Herbert Klopfer to mission leaders (Richard Ranglack, Paul Langheinrich, Friedrich Fischer), February 20, 1943, East German Mission History. He signed the letter as the Missionsleiter.

[41] Eberhard Werner of Leipzig has an original copy of this message.

[42] Ranglack, autobiography, 2.

[43] Ilse Reimer Ebert, 19.

[44] Wolfgang (Herbert) Klopfer, memoirs.

[45] Ranglack, autobiography, 2.

[46] Wolfgang Kelm, interview by the author, Hurricane, Utah, October 9, 2006.

[47] As cited by Herbert Klopfer, memoirs. He indicated that his father risked being called a traitor for fraternizing with the Danish and even took off his pistol belt while in the Esbjerg Branch meetings.

[48] Unnamed company commander to Erna Klopfer, letter, September 27, 1944, East German Mission History; trans. the author.

[49] Herbert Klopfer, interview.

[50] Ranglack, autobiography, 2.

[51] Cornelius Ryan, The Last Battle: The Classic History of the Battle of Berlin (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1995), 520.

[52] Helga Meiszus Birth, diary, April 21, 1945 (unpublished), 3; trans. the author; private collection.

[53] Kinderpost, mimeographed sheet (unpublished); private collection.

[54] Ryan, The Last Battle, 514.

[55] Birth, Diary, 8.

[56] Ingrid Bendler, memoirs (unpublished); private collection. The number twenty-four is likely too small.

[57] Wolfgang Kelm, interview.

[58] Armin Langheinrich, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, December 15, 2006.

[59] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1945, no. 104.

[60] Ranglack, autobiography, 3; “When I look back on those years, . . . I have to say that I could never have found the energy to do those things without the help of my brethren, without the help of the Lord, or without praying to the Lord.” Richard Ranglack was officially called as the president of the East German Mission by Ezra Taft Benson on March 20, 1946, and released by George Albert Smith on June 16, 1947 (via letters issued from the Church offices in London and Salt Lake City, respectively).

[61] According to research supporting this book, the total number of members of the Church in the East German Mission who died as a result of World War II was 605 (see conclusion).

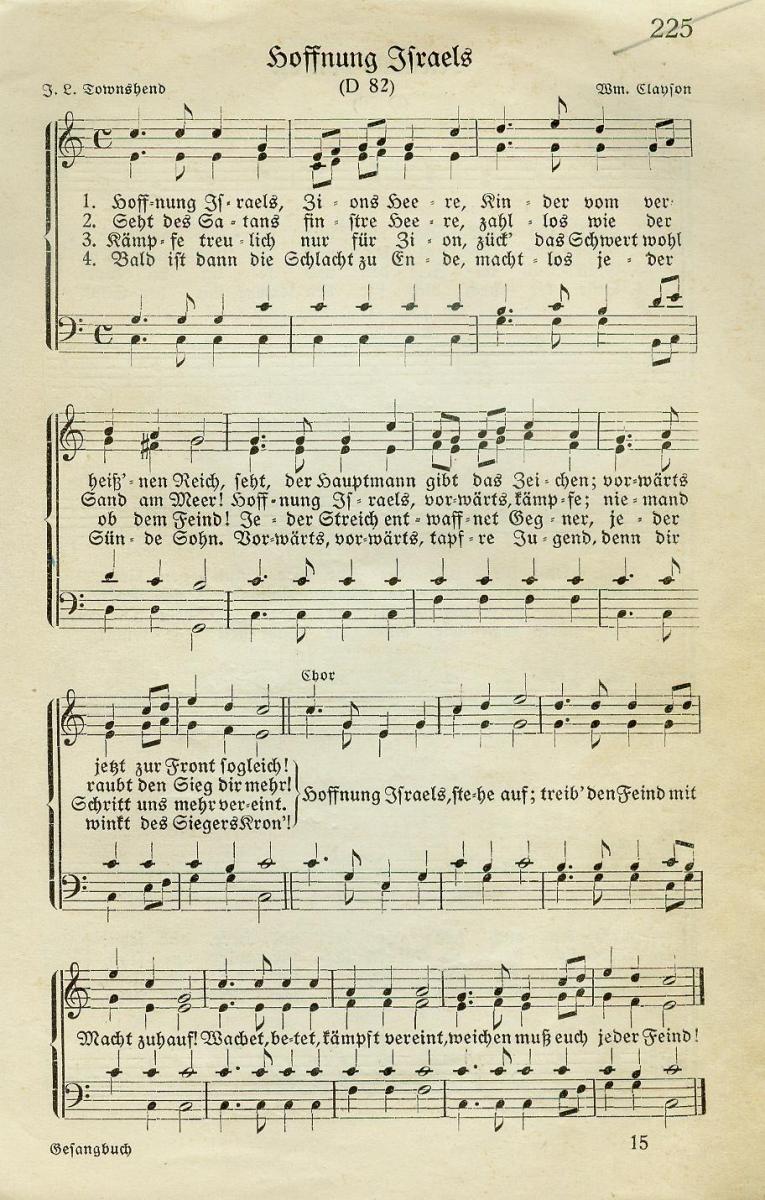

All over Germany the Saints were asked to avoid singing hymns featuring such words as "Israel" and "Zion." This page from the hymnal of Evelyn Horn Preuss shows the hymn "Hope of Israel" with the number crossed out. (E. Horn Pruess)