Driesen Branch, Schneidemühl District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 382-7.

The town of Driesen is located about fifty miles southwest of Schneidemühl on the main railroad route from the latter to Berlin. During the generation between the world wars, the town was just a few miles from the Polish border. In 1939, Driesen (now Dresanus, Poland) had about seven thousand inhabitants.

Before and throughout the war, the president of the Driesen Branch was Walter Jeske. The meetings were held in rented rooms on the main floor of the building at Kietzerstrasse 30. His daughter, Ilse (born 1921), later wrote about the meetings held there: “The branch observed the usual meeting schedule, with Sunday School in the morning and sacrament meeting in the evening. Priesthood meeting took place on Monday evening, MIA on Tuesday evening, Primary on Thursday afternoon, and Relief Society on Thursday evening.”[1]

| Driesen Branch[2] | 1938 |

| Elders | 5 |

| Priests | 2 |

| Teachers | 2 |

| Deacons | 4 |

| Other Adult Males | 9 |

| Adult Females | 27 |

| Male Children | 11 |

| Female Children | 3 |

| Total | 63 |

Walter Jeske’s son, Siegfried (born 1924), was inducted into the Wehrmacht just after finishing his apprenticeship as a machinist. He had already fallen in love with a pretty girl from the Schneidemühl Branch. The distance between the two towns did not allow frequent meetings, as he later wrote:

We had our district conference two times a year, and we had to travel to the town [Schneidemühl] where my [future] wife lived. It was there that we got to know each other. Our courting was somewhat different because we lived 75 [kilometers] from each other, and the only transportation we had was either a bicycle or the train. . . . We had to resort to letter writing only because telephones were only for rich people.[3]

President Jeske was called into military service soon after the war began. Due to the small number of priesthood holders in the branch, he authorized his daughter, Ilse, to write the reports and to send the tithing donations to the mission home in Berlin. Even after he returned in late 1940, Ilse continued to write the reports. She was later called to be the second counselor in the Relief Society while retaining all previous callings.

Members of the Driesen Branch gathered for this photograph in 1942. (R. Sward)

Members of the Driesen Branch gathered for this photograph in 1942. (R. Sward)

As a soldier in the German army in September 1942, Siegfried Jeske went through basic training in nearby Poznan, Poland (previously Posen in Prussia). For the following six months, he had additional training in the Netherlands, Belgium, and France (near Bordeaux). Then he was shipped to Belgrade, Yugoslavia, where, he said, “We were actively involved in tracking down Tito, the leader of the guerilla movement.” Such warfare usually involved women and even children, and Siegfried was soon put in a position that contradicted the standards taught to him in the family and in church. He described the potential crisis in these words:

One of the men in our company claimed to have seen the women wave to their men on top of another mountain; and as a result of that, I was asked by my commanding officer, to whom I was an aid [sic], to shoot all of the women and children. Having been a member of the Church and taught all my life not to kill, I had to ask if it was an order or merely a suggestion that I do that. He in turn asked me if I did not want to, and I answered him, “No, I [have] no desire to do so.” Well, all of the women and children did get killed by other men of the company. I realized that I could have been court-martialed for what I had done; but as a result of that, the commanding officer and I became very close friends. He found out that I was a member of the L.D.S. Church, which was not known too well in Germany. He treated me like a king after this incident.

As an infantry soldier, Siegfried did a lot of marching. After the war, he marked the routes he had walked and calculated more than three thousand miles on foot. In the spring of 1944, he was transferred to the northern sector of the Eastern Front. Soon after arriving there, he was surprised to be granted leave to go home. During his absence, his unit was involved in fierce combat that cost the lives of most of the men. He concluded, “Here again the Lord had known of this battle and the easy way to protect me from getting killed was to send me home.”

Ilse Jeske married Gerhard Pagel, a Luftwaffe airman, on December 15, 1943. After a short leave, he returned to his station in the Soviet Union. They did not see each other again for nearly six years.

Siegfried Jeske’s younger brother, Gerhard (born 1927), served in the German army for only the last few months of the war. On November 22, 1943, the Jeske family was temporarily in Berlin, where they experienced the same air raid that destroyed the mission home. It is interesting to note his comments about the property they lost when fire destroyed their apartment:

I had done some genealogical research on my mother’s line. . . . I went to some of the parishes about 100 miles east of Berlin, where my ancestors had lived, and I found many names of my people for whom I wanted to have the temple work done. This valuable information was also lost in the fire, which I regret to this day. . . . If I could have only saved those records. They were more important than anything else I possessed.[4]

In late 1944, Gerhard was drafted into the army and served seven months before being taken prisoner. Later, he wrote about ten specific occasions when he could have lost his life. Most of those were situations in which disaster struck the place he had been just hours before or involved soldiers who replaced him.

As a soldier on the Eastern Front, Gerhard took the opportunity to tell a close army buddy about the Church. Reinhard Schibblack was a typical German soldier who enjoyed cigarettes and alcohol, but he listened to Gerhard’s description of the Word of Wisdom. The two also prayed together—a common practice among soldiers facing death. According to Reinhard, Gerhard “never officially instructed me, but we often talked about God and the plans God has for us.” Just before the war ended, the two were separated, and each became a POW.[5]

The wedding picture of Ilse Jeske and Gerhard Pagel; Gerhard’s Russian captors destroyed his side of the photograph he carried with him but allowed him to keep his bride’s picture. (R. Sward)

The wedding picture of Ilse Jeske and Gerhard Pagel; Gerhard’s Russian captors destroyed his side of the photograph he carried with him but allowed him to keep his bride’s picture. (R. Sward)

In June 1944, Siegfried Jeske was wounded, and in October he was sent to a hospital in Schneidemühl for treatment. Finally, he had a chance to spend a lot of time with his fiancée (they had become engaged in May). He later wrote, “I now had the opportunity to get to know her better and found out that I really loved her.” In December, he was sent to a camp south of Munich in Bavaria.

In February 1945, Siegfried Jeske was sent to Königsberg, East Prussia, where the Red Army was advancing into Germany. “We had very little chance to get back to Germany without being captured by the Russians.” His fear was justified, because as he was traveling a few weeks later, he heard the voices of Soviet soldiers. Under heavy artillery fire, he had not noticed them approaching from behind. The first thing he saw was their bayonets pointing at him. He was captured and imprisoned.

Conditions in the Soviet POW camps were terrible, according to Siegfried:

Many of the prisoners died there. We got little or no food. Every day early in the morning a detail of prisoners was assigned to haul out a handcart full of dead prisoners, sometimes twice a day, and we all wondered when our time would come to die. We were glad when we were split up and sent off to other camps. . . . Many times we were kept at work for 24 hours, but we did not mind because many of the prisoners were sent to Siberia to work in the Russian salt mines in which many more prisoners died.

When the invaders approached Driesen in March 1945, Walter Jeske instructed his daughter, Ilse, to claim that her younger brother, Hartmut (born 1937), was her son so that the Soviets would not molest her. They walked for ten miles with a handcart over ice-covered roads to a larger town and managed to board a train. Walter did not go with the family but returned to Driesen. With her mother and siblings, Ilse arrived in Holstein (northeastern Germany) after a week on the train. They managed to find a place to live with a kind family of farmers and were there when the war ended. They were far from home and miserable. As she later recalled,

By that time, no one of us cared whether we were dead or alive. No family, no home. The big boys, Sig [Siegfried] and Rudy, still in Russia—Jerry [husband Gerhard Pagel] in Russia and my father was not with us either. Nothing to eat and we could not buy anything either.

Young Hartmut Jeske (born 1937) later recalled the evacuation of his family from Driesen:

We were told the Russians were moving into Germany, and those who didn’t want to be under Russian occupation [must leave]; there was one train going west, and we needed to be on it. So mother and my older sister Ilse and my brother Manfred, we got on that train. [We took] just a little wicker basket full of clothes is all. [But] most of the time, it was a horse-drawn carriage from town to town, and the women and small children were on the wagon, and the rest of them walked. Being young enough, I ended up on the wagon. I didn’t have to walk.[6]

Hartmut recalled these impressions of Itzehoe, Schleswig-Holstein, his family’s new home:

One unfortunate thing was that, in Itzehoe, we lived across the street from a high school, which they had turned into a hospital for those German soldiers, and every once in a while, they would bring one in on a flatbed truck, haul him in, and fix him up. I saw some of those soldiers pretty banged up. But that’s as close as I got to the [horrors of] war.

From Itzehoe it was only ten miles to Glückstadt, where the Jeske family established connections with a branch of Latter-day Saints.

For the first two years as a POW, Siegfried Jeske was allowed to write a card home with a maximum of twenty-five words. He said, “We had to be very selective with our words.” Not knowing where his parents were, he wrote to the mission home in Berlin, and his letters were forwarded to his parents and his fiancée.

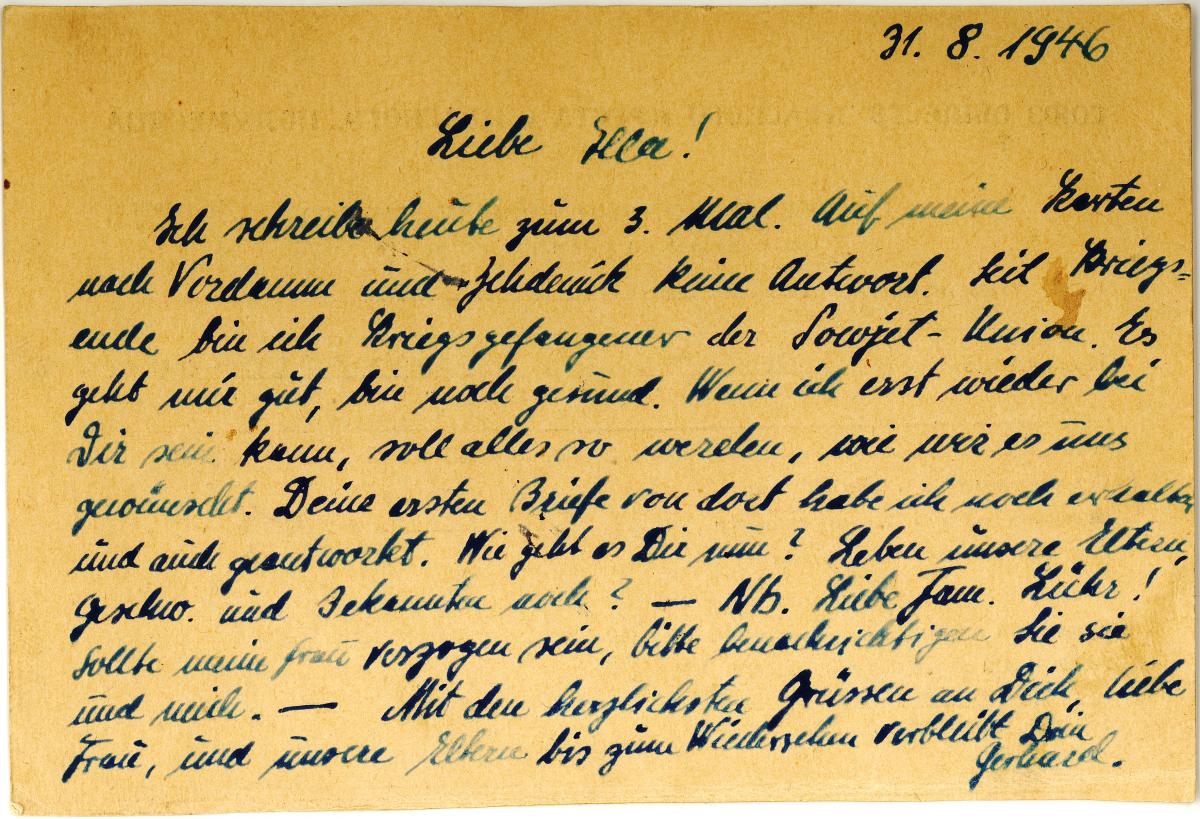

This letter was written by Gerhard Pagel to his wife Ilse from a Russian POW camp in 1946. “Are our parents still alive? Our siblings? Our friends?” (R. Sward)

This letter was written by Gerhard Pagel to his wife Ilse from a Russian POW camp in 1946. “Are our parents still alive? Our siblings? Our friends?” (R. Sward)

Gerhard Jeske was also miserable as a POW in the Soviet Union, where he spent three and one-half years—“six times as long as my life in the army. . . . It seemed like an eternity to me.” Regarding his state of mind during the incarceration, he later stated, “My faith in the gospel of Jesus Christ gave me great strength during the years in the Russian prison camps, and this was what sustained me, as well as the observance of the Word of Wisdom.”

Gerhard Pagel wrote the following to his wife, Ilse, from a POW camp in the Soviet Union on February 26, 1947:

Dear Wife,

The monthly writing day has again arrived. I haven’t received a message from you since October [19]46. My memories about you awake thoughts of the surroundings. That these have changed completely. In the case of my return, I hope to see you again healthy, and wish that our new secure home will meet our needs in every respect. How do you find your new surroundings? Many of my comrades here are from there. Things are bearable here. But there is a lot to wish for, especially a return home and freedom. Then it is my mission to pursue and make up for our happiness in Glückstadt. Please greet the parents and the boys. With heartfelt greeting to you, I am your Gerhard.[7]

On March 1, 1949, Siegfried was surprised to be released and sent home. For two days, he rode a freight train to Germany and was set free just inside West Germany, because his parents had settled there after fleeing Driesen. His fiancée was still in East Germany but was soon allowed to join him in the West. They were married on August 20, 1949.

Reinhard Schibblack returned to Berlin in June 1949 and was fortunate to find his friend, Gerhard Jeske, who immediately took him to church. Reinhard was readily accepted by the members of the Church in East Berlin and was baptized soon thereafter.[8]

Gerhard Pagel was released in the Soviet Union in October 1949 and joined his wife, Ilse, in Schleswig-Holstein.

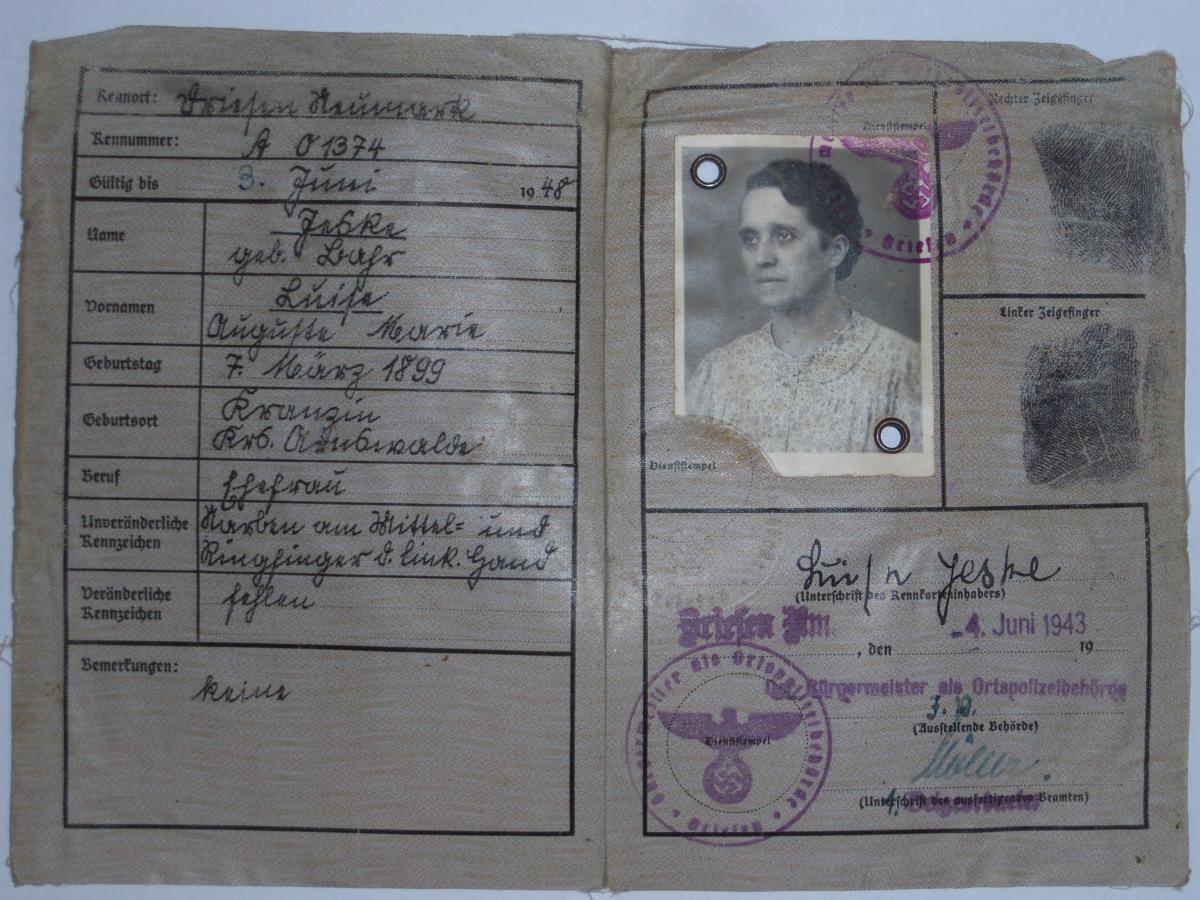

This is the standard personal identification document issued to German citizens. Luise Jeske was a member of the Driesen Branch. (H. Jeske)

This is the standard personal identification document issued to German citizens. Luise Jeske was a member of the Driesen Branch. (H. Jeske)

Branch president Walter Jeske finally left Driesen in early 1947. He may have been the last member of the Church in the town. All members of the branch were expelled from the area by the new Polish government, and the branch ceased to exist.

No members of the Driesen Branch are known to have died during World War II.

Notes

[1] Ilse Jeske Pagel, fireside address (unpublished); private collection.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[3] Siegfried L. Jeske, fireside address (unpublished); private collection.

[4] Gerhard Jeske, autobiography, 1979, MS 17127; Church History Library.

[5] Church News, August 1, 1970, 14.

[6] Hartmut Jeske, interview by Michael Corley, Ogden, Utah, March 7, 2008.

[7] Gerhard Pagel to Ilse Pagel, letter, February 26, 1947; private collection.

[8] Reinhard Schibblack, autobiography (unpublished); private collection.