Dresden Altstadt Branch

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 231-42.

Called the “Florence on the Elbe,” the city of Dresden was truly a cultural gem in Germany in 1939. Famed internationally for its many museums and architectural monuments, the city was also known as the home of one of the most treasured brands of porcelain in Europe. The former capital city of the kingdom of Saxony, Dresden was a railroad center but otherwise had no military or industrial significance. The population of the city at the time was approximately 650,000.

| Dresden Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 18 |

| Priests | 2 |

| Teachers | 10 |

| Deacons | 20 |

| Other Adult Males | 79 |

| Adult Females | 203 |

| Male Children | 16 |

| Female Children | 17 |

| Total | 365 |

At the onset of World War II, the East German Mission records indicated the existence of only one branch of the Church in the city of Dresden. It was called simply the Dresden Branch, but was later referred to as the Altstadt (old city) Branch. It is clear from eyewitness testimony that by 1942 or 1943, a second branch existed under the name Neustadt (new city) Branch. They will be treated here as two coexistent branches for most of the war. The official membership shown in the table below represents the only branch in the city at the end of 1939.

Elder Leo Van Gray of Pocatello, Idaho, was one of the last foreign missionaries to leave Dresden before World War II began. The following entries in his diary reflect the tension felt by missionaries and Altstadt Branch members alike as peacetime drew to a close:

Thursday 24 August: The warning has come. Our trunks are to be packed and ready—in case. . . . Shortly after dinner the telegram came. After that I helped pack a stove into the Altstadt Church house.

Friday 25 August: The tension is surely growing tonight. Now things are beginning to move with fast rapidity. Never in my life have I seen things so quickly fired up. After a dinner at the Brux’s a telegramm came to the house stating “Come Berlin Immediately Trunks Same Train.” [Elders] McKay, Hawkes, and Montague was [sic] resting while I was writing a letter, but I immediately jumped on my bike and ran over to Mutties [Sister Schäckel] and told [Elders] Sorenson and Nuttal the sad news. The Rigby’s had just left there, and I caught up with them at the German Hygiene Museum. They were very dissapointed [sic]. I went home and packed. All seven of us tried to eat at the house but were unsuccessful. . . . Went home and finished packing.

Saturday 26 August: Awoke early this morning. Everything seems to be a hustle and bustle here in Dresden. I went right out to Sister Dotters and picked up two white shirts she [had] washed for me. She was rather blue. Her husband left last night for the front. I came back to breakfast and the finals in packing. Went over to the Church house to get a Kodak for Montague and tell Sorenson to get a wagon. All trucks and horses have been confiscated this morning. We left Dresden at 12:54, arrived Berlin about 3:30.[2]

Annelies Höhle recalled that American missionaries had assisted members in renovating the rooms for the Altstadt Branch when the property was first acquired:

When we started, the missionaries were still here and helped with the construction and painting. Suddenly they were gone, and we thought, well, they will be returning soon. The branch house was dedicated in early September.[3]

Herber Schroeter recalled the departure of the American missionaries: “That was a really sad experience. They didn’t want to leave Germany. They loved Dresden. . . . It happened so fast, they were gone, and the next Sunday we had no missionaries anymore. There was a lot of sadness.”[4]

The rooms in which the Altstadt Branch met before the division were at Königsbrückerstrasse 62 on the main floor. Following the establishment of the Neustadt Branch, the Altstadt Branch found rooms to rent at Zirkusstrasse 33 (south of the river and just east of the downtown). The Neustadt Branch stayed on Königsbrückerstrasse, moving to number 93 (about one mile farther north).

Harald Schade (born 1930) described the rooms at Königsbrückerstrasse 62 as follows:

Our branch met in an old restaurant. In the front there was a big grocery store and the other rooms were occupied by our branch. We had a big kitchen, an entrance hallway, the main hall with a podium, and an adjoining room. The choir sat in the first few rows on the main floor. We used the podium for a theatre club two or three times a year before the war. We had a picture of President Heber J. Grant hanging on the side wall. Above the podium there was a phrase painted: “The glory of God Is intelligence.”[5]

The first meeting on Sunday mornings was priesthood meeting. The Sunday School followed but was shortened on the first Sunday of the month to accommodate a fast and testimony meeting. Sacrament meeting was held at 6 p.m. in the winter and 7 p.m. in the summer. There were approximately ninety people in church on Sundays. The full slate of meetings continued during the week, as Harald recalled: “We had Relief Society on Tuesday, and Monday nights we had Bible class. On Wednesday afternoons we had Primary and MIA in the evening hours. On Thursday nights we had our choir practice.”

The chapel of the Altstadt Branch on Zirkusstrasse. The banner reads: “Truth will prevail.” (K. Bartsch)

The chapel of the Altstadt Branch on Zirkusstrasse. The banner reads: “Truth will prevail.” (K. Bartsch)

Herbert Schroeter (born 1923) recalled a phrase from scripture on an embroidery hanging on the pulpit in the chapel: “‘Be ye doers of the word, not hearers alone.’ There was also a spiral staircase, and I remember trying to go down it to a room [in the basement] where we had our kindergarten. On the front of the building was a sign with the words ‘Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der letzten Tage’ in black and gold.”

The president of the Dresden Altstadt Branch throughout World War II was Willy Bohry.

The Schade family lived at Hindenburgufer 16 in the Altstadt. Harald Schade recalled that it took about thirty minutes to cross the Elbe and walk north to the church. Herbert Schroeter often rode to church with his mother in his grandfather’s car and arrived early. Between meetings on Sundays, Herbert and his mother enjoyed a good soup in a restaurant across the street or spent the time with other members of the branch.

Harald’s sister, Edith (born 1919), served her Pflichtjahr from 1939 to 1940 in the home of a wealthy couple without children. Having graduated from a college preparatory school, she then applied for admission to a college for teachers. In an interview with the director, she was told that as a member of an American church, she had a very different worldview than the one espoused by Germany’s government. Later, she received a letter from the ministry of education in Berlin stating that she could not be admitted to the program. “In this case,” she later explained, “it seemed to be a big disadvantage to be a member of the Church.” She then found employment in a large company providing products for the military.[6]

On May 14, 1941, Max Schade (the father of Edith and Harald) passed away. After his death, his widow, Martha Schade, found a smaller apartment at Segnitzerstrasse 25 in the Neustadt. She and her children began to attend church in the Neustadt Branch.

Dieter Dünnebeil (born 1931) was baptized in the Elbe River. “We didn’t have any other place to do baptisms,” he explained. It was in a flood stage at the time (spring 1939), and he was a bit scared as he entered the water. “But they held on to me,” he recalled.[7]

Annelies Höhle gave birth to a son named Winfried in 1942. He was born one month early and apparently showed signs of slow development early on. Sister Höhle had not heard of the Nazi program of euthanasia (so-called “mercy killings”) but was concerned that Winfried might be taken from her. She later described her fears:

I had to be very careful that I never went anywhere with him where he might stand out. I didn’t take him to get shots. . . . I just had to watch myself. I think still to this day that it was some sort of an inner voice telling me, “Don’t go out with him.” An inner feeling. And if I hadn’t followed this voice, I might not have had Winfried for long. They probably would have taken him away.[8]

Herbert Schroeter finished his activities in the Hitler Youth in 1941 at the age of seventeen. “We had been taught about the greatness of Adolf Hitler and how he was going to change Germany in four years’ time.” Then he was called into the Reichsarbeitsdienst and worked in Poland for eight months constructing an airfield. On October 6, 1941, he was drafted by the Wehrmacht and sent to Officer’s Candidate School in Dresden. As he later explained:

I was proud to be an officer cadet. I got a better uniform, better pay, better food, and I looked really nice. I was at an army post in Dresden Neustadt, not at the front like the rest of them. It lasted longer than basic training, because I had more learning to do to become an officer. And I went home every weekend, and I got to go to Church with my mother.

Herbert was still in training in Dresden when word came that his father, Bernhard Wilhelm Schroeter, had been killed by partisans in the Soviet Union. “They sent his personal effects back [his money and pictures of the family] and told us that he had died for greater Germany,” he recalled. By early 1942, Herbert was a lieutenant serving near Kiev, Ukraine. “At that time the German army progressed every day, we went forward and forward. . . . I fought in so many battles. . . . I was in the Sixth Army.”

On November 22, 1942, the German Sixth Army was encircled in Stalingrad, and Herbert Schroeter was in the middle of the city embroiled in bitter house-to-house combat. Just before Christmas, he was awarded the Iron Cross First Class for bravery, and the medal was presented personally by General Friedrich Paulus, commander of the Sixth Army. For the next few weeks, still wearing his summer uniform, Herbert endured temperatures far below zero and watched as his comrades lost ears, fingers, and toes to frostbite. By February 2, 1943, all attempts to reinforce the Sixth Army had failed and Field Marshall Paulus (recently promoted) had no option but to surrender the entire force. Some 70,000 German soldiers had been killed, and the Soviets counted 91,000 prisoners in what would become Hitler’s greatest debacle of the war.[9]

Herbert Schröter (left) running through the streets of Stalingrad under fire. This photograph was taken by his friend who was killed minutes later. (H. Schröter)

Herbert Schröter (left) running through the streets of Stalingrad under fire. This photograph was taken by his friend who was killed minutes later. (H. Schröter)

As the German prisoners were being marched away from the ruins of Stalingrad, Herbert Schroeter met a high-ranking officer who tried to convince him that they had essentially no chance of surviving. Herbert and a friend decided to take their chances of escape with the officer, and the three men moved bit by bit toward the side of the road. As the sun set, they dropped to the ground and tried to appear to be dead. Herbert’s account continued:

The last [Russian guard] walked by us and we looked around, nobody behind us anymore so we stood up . . . and walked back the way we came. The officer had a map and an idea about where the next village might be. It was peaceful, no shots, no nothing, just dark. . . . Then a jeep came toward us very slowly—an American jeep [produced for the Soviets]. What were we going to do? We lay by the side of the road and when they came by, we jumped up and jerked the doors open and pulled the men out. They were taken totally by surprise, speechless, not expecting anything like that. We told them to take off their coats and their guns and they were not rebellious. In the back of the jeep was a big sack of Russian bread. We made the Russians help us turn the jeep around, sliding it on the frozen road. Eric, the other soldier, knew how to drive the jeep so we headed west. But we had to be careful, because we might come upon some Germans, and they would kill us because we looked like Russians. Then a column of Russian vehicles with about fifty soldiers approached, and again we wondered what we should do. One driver stopped, rolled down his window, and spoke to us. Our driver knew a little Russian and said a few words in reply. The Russian told us that the German lines were about ten kilometers [six miles] ahead and that we shouldn’t go that direction. Our man said, “Thanks for the information.” They left and we drove on, stopping when we came to a forest. We made a fire and warmed up our bread. Then one man stood guard with the gun because the wolves there were really mean.

The next day, the three men abandoned the jeep and walked toward the west with the sun as their guide. After crossing territory that yielded no signs of life, they spent the second night without a fire. Fortunately, they found a haystack and crawled inside to sleep. The third night was also spent in a haystack, amid a landscape of desolation. In the late afternoon of the fourth day, they spotted some soldiers in white winter clothing on the horizon. Not knowing whether the soldiers were friend or foe, they moved very slowly in that direction until they could determine that the soldiers wore German helmets and carried German rifles:

We ran toward them, opening our Russian coats to show them our German uniforms, while yelling “Don’t shoot! We’re Germans! We escaped from the battle of Stalingrad!” They took us to their commander who asked how we could have survived. We showed them our bread supply. . . . Then for three days we could eat, . . . mostly goulash and potatoes and gravy. It was really good. And we got new uniforms and stuff, and then they divided us up.

Back home in Dresden, most of the members of the Altstadt Branch were living a life still relatively free from hardship. In church, however, at least one thing was different: by January 1943, the meetings were being held at Zirkusstrasse 9. It is not known why the move took place, but city officials often confiscated large rooms to house homeless people.[10]

Herbert Schröter (left background circled) in the ruins of a factory during the battle of Stalingrad (H. Schröter)

Herbert Schröter (left background circled) in the ruins of a factory during the battle of Stalingrad (H. Schröter)

Throughout the war, the Latter-day Saints in Dresden were issued ration cards for food, as was the case all over Germany. Dieter Dünnebeil remembered that his family always had enough food and never starved. “You had to stand in line a lot when the stuff came in [to the stores], but it was organized.” In fact, Dieter’s family got by a little bit better than their neighbors, because they used their tobacco ration cards to trade for other food items. “Maybe it wasn’t right, but what else could you do? You had to survive!”

In 1943, Paul Gräber sent his family from Berlin to a small town south of Dresden to live with relatives. Brother Gräber was in the army and wanted to know that his family was safe from the constant air raids plaguing the Reich capital. His wife and two daughters spent the rest of the war in Wittgensdorf, nine miles south of Dresden. Daughter Karin (born 1940) recalled that it took nearly three hours to get to Dresden to attend meetings in the Altstadt Branch. Because of the long trip, they could only attend one meeting each Sunday.[11]

Hitler Youth meetings took place at times on Sundays, but Harald Schade did not attend. His mother explained to the leaders that church meetings took priority, and fortunately there was no penalty for Harald’s absence. In 1944, at age fourteen, he hoped to be accepted into a cavalry group of the Hitler Youth, but he was too small and was thus turned down.

Following his escape from Soviet captivity in February 1943, Herbert Schroeter witnessed the gradual retreat that took the German army from deep inside Russia back toward the German Reich. It was an agonizing retreat and the result—defeat for Germany—was clear to Herbert well in advance. In early 1945, he was taken prisoner by the Red Army in eastern Germany.

In what was likely the worst disaster to ever occur on German soil in a single twenty-four hour period, the city of Dresden was attacked by Allied airplanes on February 13–14, 1945. At the time, the city was literally being overrun by thousands of refugees from the eastern German provinces, fleeing the invading Soviets. Many of the refugees were actually living in the streets, unable to find housing or still hoping to board a train for towns farther west. The justification for the attacks was the assumption on the part of the Allies that Dresden was a key railroad transportation hub and a staging center for troops to be sent to the east to oppose the Soviets. According to historian David Irving:

By the beginning of February 1945, the capital of Saxony was . . . virtually an undefended city, although the Allied Bomber Commands might well plead ignorance of this. In addition the city was . . . devoid of first-order industrial, strategic, or military targets-in-being.[12]

At 10:13 p.m. on February 13, the first British bombs were dropped on Dresden. Irving described the tactics employed against Dresden as follows:

First the windows and roofs would be broken by high-explosive bombs; then incendiaries would rain down, setting fire to the houses they struck and whipping up storms of sparks; these sparks in turn would beat through the wrecked smashed roofs and broken windows, setting fire to curtains, carpets, furniture, and roof timbers.[13]

The second wave of Royal Air Force bombers flying at 20,000 feet released their loads over an already fiercely burning Dresden beginning at 1:24 a.m. on February 14. By the time the two RAF attacks had concluded, hundreds of bombs weighing as much as 8,000 pounds each had been dropped along with 650,000 incendiary bombs. A total of 1,400 aircraft had participated in the two attacks.[14] Rescue crews were summoned to Dresden from miles away and were already at work in the early morning hours of February 14. The city was in shock, and nobody could have imagined that the carnage was not yet over.

A member of the crew of the last British Lancaster bomber to drop its load over Dresden in the second attack later described the experience in these words:

There was a sea of fire, covering in my estimation some 40 square miles. The heat striking up from the furnace below could be felt in my cockpit. The sky was vivid in hues of scarlet and white, and the light inside the aircraft was that of an eerie autumn sunset. We were so aghast at the awesome blaze that although alone over the city, we flew around in a stand-off position for many minutes before returning for home, quite subdued by our imagination of the horror that must be below. We could still see the glare of the holocaust thirty minutes after leaving.[15]

Just after noon on February 14—at 12:12 p.m.—the third attack began. This time it was the United States Eighth Air Force with a total of 1,350 Flying Fortresses, Liberators, and fighter escorts. The bombers dropped a total of 771 long tons of explosives on the burning city.[16] Following this bombing run that lasted only eleven minutes, American fighter planes raced low over the city, seeking out remaining targets of interest. Many concentrated their attacks on the banks of the Elbe River, where thousands of civilians had sought refuge from the flames and the smoke of the burning city.[17]

In their apartment house on the corner of Fürstenstrasse and Dürerstrasse (about one mile from the center of town), the Speth family heard the sirens at about 10:30 p.m. on February 13. A few minutes later, they huddled in their basement with their neighbors and felt the vibrations of bombs landing nearby. After forty-five minutes, they were relieved that they were still alive, and their apartment building was apparently intact. However, the power was out, and they decided to stay in the basement—a very wise decision, because within hours, the second attack began. Daughter Dorothea later recalled the situation:

It was a terrifying experience! But when the silence finally returned, we were still alive. . . . However, we were trapped in the basement. . . . The stairway, our [main] exit, was blocked by the fire. The only way out was a hole in our basement wall connecting the basement with the house next door.[18] . . . it was barely big enough to crawl through. We couldn’t take anything with us. Our family and an older couple who lived on our floor managed to escape through this hole. Most of the homes in our area of the city were now destroyed or burning, and the few that remained would soon be on fire. We all realized that we needed to get away from the burning houses immediately![19]

Brother Speth began to lead the family (his wife and four daughters) directly north on Fürstenstrasse toward the Elbe River, where they believed they would escape the fires and find better air to breathe. Suddenly, he changed directions and went east on Dürerstrasse. His wife, several yards behind, called to him to tell him to continue straight up Fürstenstrasse, but the rushing winds of the firestorm drowned out her voice. As she hesitated to follow him, preferring to take the wider street, a daughter admonished her with the words “Mom, let’s follow Dad; he holds the Priesthood!” Yielding to this advice, she hurried to catch up with her husband, who had turned north into the narrow Glückstrasse toward the river. A few minutes later, they were safe in one of the buildings of the Johannstadt Hospital and learned what could have happened had they gone down the wide Fürstenstrasse. Dorothea recounted that

A neighbor lady entered the building. . . . [She and her husband] decided to walk straight down [Fürstenstrasse] to the river. Her husband . . . walked very quickly leading the way, but she . . . could not follow so quickly and lagged behind. Suddenly she saw her husband burnt alive in front of her eyes. Unknown to anyone, liquid phosphorus from one of the bombs had covered the street. It could not be seen but was immediately ignited whenever anyone stepped on it. . . . If we had not followed our father, we would have walked right into that liquid phosphorus. I learned that night how important it is that we follow the priesthood.[20]

Dieter Dünnebeil’s family lived in the suburb of Leuben, five miles southeast of the center of the city. They knew the routine when the air-raid sirens sounded: for years, they had taken their little bags and headed down into the basement of their apartment house. Nothing had ever happened before, and he was thinking that night, “Here we go again for nothing.” The group huddling in their basement that night included the building’s residents and many refugees as well. Later, Dieter had a clear recollection of that tragic night:

All of a sudden we heard from far away boom, boom, boom—explosions. We had only heard that once before, about two years earlier. We figured it wouldn’t take long, maybe a half hour. Then the lights went out, and we knew it was serious. . . . That was around eleven o’clock, so we went to bed. Then at two o’clock, we again heard boom, boom, boom. The siren was right across the street from our apartment house, and it scared you out of your bed. Then we went downstairs again.

Dieter and his family were frightened by the smoke coming from downtown the next morning. American airplanes were also screaming past, searching out specific targets. There was no radio news, so they were unsure of what had happened. They did not go toward the downtown, “because we were scared now, too. We thought this was the end of the world. Nothing happened that serious before. So we just hung around, and we tried to get some more food, [you know] how you act in emergencies.” Eventually, the Speth family (having spent the night in the Johannstadt Hospital) arrived at the Dünnebeil home and described the terror of the events that had taken place in their downtown neighborhood. Soon, several other LDS families (refugees from eastern Germany) were taken into the Dünnebeil apartment.

Christa Gräber (born 1934), Karin’s older sister, was ten years old when Dresden was destroyed. She recalled that their mother got them out of their Wittgensdorf house when they heard the bombs fall and saw the lights of the fires from ten miles away. They hid in ditches near their home. Following the attack on Dresden, the Gräbers did not attend church for several weeks and school ended for Christa for the year.[21]

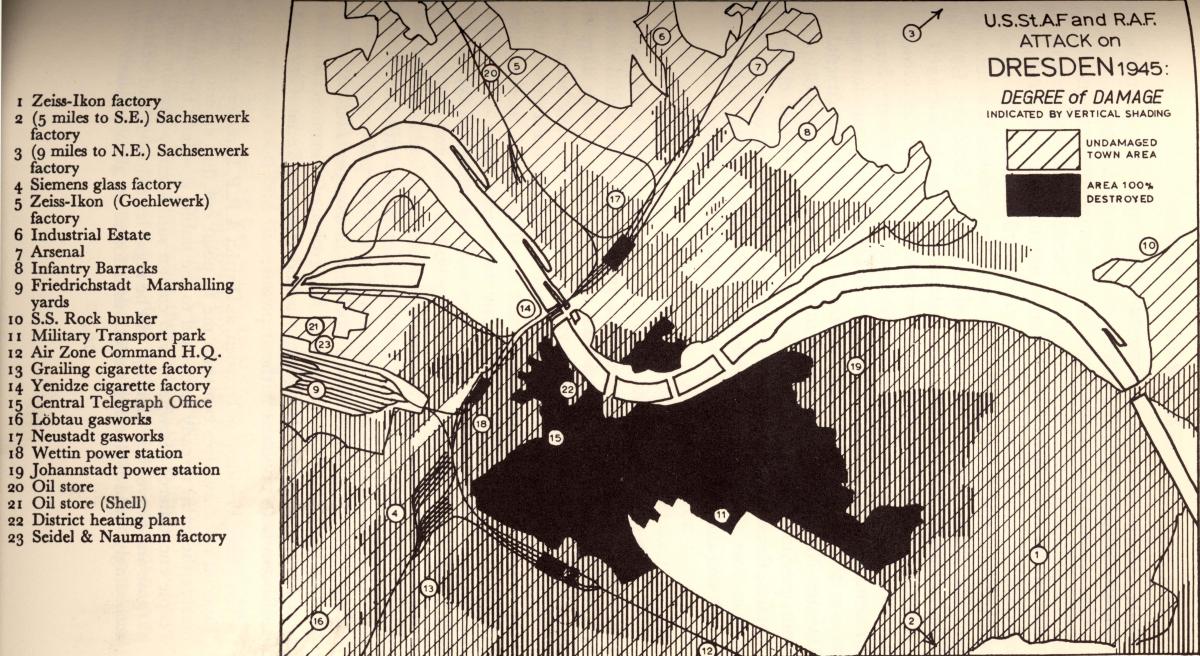

This map from Irving’s The Destruction of Dresden shows the degree of destruction in various neighborhoods. The black represents total devastation. (D. Irving)

This map from Irving’s The Destruction of Dresden shows the degree of destruction in various neighborhoods. The black represents total devastation. (D. Irving)

The damage inflicted on Dresden surpassed that of any other aerial attack in Europe in World War II. Irving reported the destruction of 1,600 acres of city territory. Dresden city authorities exerted great efforts to identify the victims, but with so many refugees and transients in the city at the time, this task was daunting. The total killed was estimated at 135,000. Most of the bodies were buried in mass graves or incinerated in enormous funeral pyres, where they were found. The downtown residential areas were obliterated, while the largest railroad stations, bridges, and the Neustadt army post survived with little damage.

| Population of Dresden residents | 650,000 |

| Estimated refugees in Dresden | 300,000 to 400,000 |

| Homes totally destroyed | 75,358 |

| Homes badly damaged | 11,500 |

| Total deaths on February 13–14, 1945 | 135,000 |

| Residential area destroyed | 1,600 acres[22] |

Stories of horrific deaths are common and eyewitnesses reported seeing people as human torches emerging from basement shelters or jumping into the Elbe. However, due to the nature of firestorms, most victims died of suffocation. The flames from tall apartment houses along narrow streets needed oxygen to burn and sucked the air from the lungs of people close by. According to Irving, “Probably over seventy per cent of the casualties were caused by lack of oxygen or by carbon monoxide poisoning.”[23] For days following the attack, entire groups of civilians in air-raid shelters were found dead but in normal physical condition, the victims appearing as if they had simply fallen asleep.

Annelies Höhle later described the fate of the Altstadt Branch members and their meeting rooms:

[The church] was destroyed, yes. Actually, in the entire bombing, as far as I know, we lost only one sister. That was Sister Wiedemann, who lived in the center of the city, right downtown. The others all showed up after the bombing.[24]

One of Christa Gräber’s vivid memories regarded conditions outside of Dresden in the weeks following the firebombing. She recalled diving into ditches on the way home when enemy fighter planes came around looking for people as targets. “I knew they were coming to shoot people, and I saw them, and we ran from our little street where we walked on, it was just a street, and threw ourselves in a ditch, and I did that many times.”

The Red Army arrived in Dresden in the first week of May 1945. Residents had hoped that the Americans would get there first because rumors of Soviet misdeeds were daily fare among refugees from the east. Dieter Dünnebeil recalled that there was no fighting in his Dresden suburb of Leuben because German soldiers were intent on heading west to surrender to the Americans. Dieter’s family was not harassed by the invaders, but he recalled hearing women in their neighborhood scream during the night. He remembered being happy to hear that Hitler was dead; at least the bombing would stop, he thought.

Looking back on the war, Dorothea Speth told how her family lost their home and nearly all of their material possessions. However, before the terrible air raid, living conditions had not really been bad:

During World War II, we always had enough to eat, and we still had enough of a variety of things to eat. Things were rationed, but we still had enough sugar, we still could buy some chocolate, and we still had meat at least for Sundays or once during the week. We always had enough bread, and we always had enough potatoes. I never remember being hungry.[25]

In the summer of 1945, Paul Gräber returned from his service with the army. He had managed to escape capture and as such was one of the first Latter-day Saint soldiers to come home. However, he was suffering from a recent wound, having been shot through the mouth. His daughter, Karin, recalled his sufferings: “I remember we sat down to eat and he always took stuff out of his mouth, always. Broken bone, broken teeth, splinters coming out of his mouth.” Just three weeks later, Brother Gräber was dead. He had eaten some toadstools found in a local forest and died of poisoning.

Herbert Schroeter spent part of his fours years of Soviet imprisonment in Siberia. (“I didn’t like that at all!”) He was finally released on September 17, 1949, in Frankfurt/

When I went to war . . . my testimony was not strong. I knew the gospel was true. They told us that every Sunday. We read in the Book of Mormon and the Bible. . . . I don’t know how I survived, but I prayed a lot. . . . I wasn’t strong, but I gained my testimony in the war.

Dieter Dünnebeil remembered fondly the Altstadt Branch in wartime. “What kept us together was that we were like a family. We grew so close together and took every possibility and chance to be together, to see each other, and keep in contact.”

At the time of the firebombing of Dresden, the Altstadt Branch probably had more than two hundred members of record. As of this writing, only two members are known to have perished during the attacks of February 13–14, 1945, but many others died from a variety of other causes.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Dresden Altstadt Branch did not survive World War II:

Theresia Amalie b. Waldenburg, Sachsen 31 Jul 1864; dau. of Carl Friedrich Paling and Christiana Theresa Berger; bp. 9 May 1929; conf. 9 May 1929; m. —— Ballmann (div.); missing as of 10 Dec 1948 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 174; FHL Microfilm 25717, 1930 Census; IGI)

Paul Paul Balke b. Zeithain, Dresden, Sachsen 15 Feb 1892; son of Wilhelm Franz Balke and Emilie Ernestine Weser; bp. 14 Dec 1923; conf. 16 Dec 1923; m. 9 Aug 1924, Marta Waechtler; d. 24 Mar 1943 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 1; IGI)

Rudolf Erwin Baron b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 8 Aug 1917; son of Alfred Fritz Baron and Meta Caecilie Antoine Kosalek; bp. 24 Mar 1934; conf. 24 Mar 1934; ord. deacon 17 Nov 1935; m. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 20 Jun 1942, Erika Steiner or Erika Margareth Heine; k. in battle 8 Apr 1945 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 177; CHL 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 744–45; IGI)

Minna Erna Barthel b. Zongenberg, Thüringen 17 Sep 1911; dau. of Karl Barthel and Mina Boehme; bp. 21 Jul 1927; conf. 21 Jul 1927; missing as of 10 Dec 1948 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 2)

Klara Hedwig Brux b. Werdau, Zwickau, Sachsen 11 Dec 1867; dau of Adolf Brux and Anna Weidlich; bp. 20 Nov 1926; d. accident 14 Apr 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 21, 25 May 1941, 84; IGI)

Marie Czekalla b. Mokan, Schlesien 9 Aug 1900; dau. of Franz Czekalla and Helena Schaum; bp. 31 Jan 1920; conf. 1 Feb 1920; missing as of 10 Dec 1948 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 10)

Karl Felix b. 1875; d. old age Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 15 May 1941 (Schade-Krause; Sonntagsgruss, no. 24, 15 Jun 1941, 96)

Abraham Johannes Gommlich b. Wilschdorf, Dresden, Sachsen 28 Nov 1922; son of Max Paul Hermann Gommlich and Helene Martha Hegewald or Uhlig; MIA Stalingrad, Russia Jan 1943 (Heinz Hegewald; IGI)

Manfred Werner Gommlich b. Wilschdorf, Dresden, Sachsen 5 Aug 1925; son of Max Paul Hermann Gommlich and Helene Martha Hegewald or Uhlig; MIA Stalingrad, Russia Jan 1943 (Heinz Hegewald; IGI)

Max Paul Hermann Gommlich b. Rähnitz, Dresden, Sachsen 14 Dec 1900; son of Max Paul Hermann Gommlich and Klara Minna Mueller; bp. 21 Oct 1910; m. Raehnitz, Dresden, Sachsen or Wilschdorf, Dresden, Sachsen 27 Dec 1921, Helene Martha Hegewald or Uhlig; 2 or 3 children; MIA Stalingrad, Russia Jan 1943 (Heinz Hegewald; IGI; AF)

Klara M. Louise Herrmann b. Bülzig, Merseburg, Sachsen, Preussen 9 Aug 1869; dau. of Edward Herrmann and L. Knoblauch; bp. 7 Sep 1926; conf. 7 Sep 1926; m. —— Siegert; missing as of 10 Dec 1948 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 141)

Alfred Arthur Klemm b. Demnitz, Preussen 27 Feb 1883; son of Gustav Klemm and Auguste Schubert; d. old age 22 Sep 1941 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1410–11)

Dora Liebsch b. Bautzen, Sachsen 24 Apr 1908; missing as of 1943 (CHL 2458, form 42 FP, pt. 37, 748; FHL Microfilm 271387, 1935 Census)

Johanna Gertrud Liepke b. Oberneukirch (?) 10 Feb 1898; dau. of Gustav Liepke and Ida Weber; bp. 20 Nov 1926; conf. 20 Nov 1926; m. —— Tietz; 2m. 3 Jun 1922, Hermann Buhr; missing as of 10 Dec 1948 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 153)

Willy Walter Marx b. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 6 Sep 1919; son of Rudolf Marx and Dora Elisabeth Scherfler; bp. 6 Jul 1938; conf. 6 Jul 1938; m. 19 Sep 1940, Edith Goldammer; d. 21 Nov 1941 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 86; IGI)

Amalie Auguste Mietsch b. Elsterwerda, Dresden, Sachsen 20 Jun 1863; dau of Karl Mietsch and Rosa Fichte; bp. 10 Sep 1923; conf. 10 Sep 1923; m. Mar 1889, Herrmann Boehme; missing as of 10 Dec 1946 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 180; IGI)

Johanna Pauline Niedergesaess b. Jenkwitz, Schlesien, Preussen 19 Jun 1858; dau.of Kurt Elschker and Johanna Charlotte Christiane Niedergesaess; bp. 19 Jun 1937; m. Meissen, Dresden, Sachsen 3 Feb 1894, Friedrich Wilhelm Stiefler; d. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 29 Jan 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 11, 16 Mar 1941, 43; IGI)

Max Hermann Reschke b. Grosszschachwitz, Dresden, Sachsen 4 Aug 1907; son of Richard Paul Reschke and Emma Bertha Clara Dietrich; bp. 27 Sep 1921; m. 28 Oct 1933, Gertrud Frieda Lassmann; d. kidney disease 8 or 18 Oct 1939 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1939 data; IGI, PRF)

Agnes Hildegard Rieger b. Dresden 2 Apr 1911; dau. of Joseph Rieger and Emma Worker; bp. 15 May 1924; conf. 18 May 1924; missing as of 1943 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 181; CHL 2458, Form 42 FP, Pt. 37, 748)

Max Emil Paul Schade b. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 19 May 1874; son of Karl August Leberecht Schade and Emilie Henriette Beckert; bp. 6 Oct 1905; ord. elder; m. Dresden 1 Oct 1907, Martha Clara Elisabeth Marx; 8 children; d. old age Dresden 14 May 1941 (Schade-Krause; Sonntagsgruss, no. 24, 15 Jun 1941, 96; CHL Microfilm MS 16596; IGI; AF)

Bernhard Wilhelm Schröter b. Grosswaltersdorf, Freiberg, Sachsen 9 Apr 1898; son of Julius Bernhard Schroeter and Marie Clara Daehnert; bp. Dresden, Sachsen 21 Oct 1922; ord. priest; m. Großwaltersdorf 21 or 22 Sep 1922, Helene Martha Zöllner; 3 children; lance corporal; k. in battle Ramenje, Tschudowo, Russia 23 or 25 Nov 1941; bur. Ramenje, Tschudowo, Russia (Schroeter; www.volksbund.de; IGI; AF)

Elly Carlotte Schütze b. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 27 Nov 1913; dau. of Karl August Schütze and Marie Elisabeth Lehmann; bp. 4 Feb 1922; m. Herbert Thummler; d. as a result of air raid Dresden 13 Feb 1945 (Matt Heiss; CHL 2458, Form 42 FP, Pt. 37, 744–45; IGI)

Horst Georg Schulze b. 3 Dec 1908; son of Emma Louise Jungfer; ord. deacon; m.; MIA 1943 (CHL 2458, Form 42 FP, Pt. 37, 748; FHL Microfilm 245260, 1930/

Hermann Helmut K. Fr. Sieber b. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 11 Jan 1907; son of Samuel Koch and Johanna Sieber; bp. 14 Dec 1923; conf. 16 Dec 1923; missing as of 10 Dec 1948 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 139)

Franz Ferdinand Helmut Speth b. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 30 Mar 1922; son of Joseph Speth and Frieda Hedwig Winkler; bp. Dresden 13 Oct 1930; ord. deacon; k. in battle Minsk, Bellarus, USSR 19 Mar 1943 (H. Schroeter, D. Speth Condie; G. Speth Kehaya; IGI; AF)

Selma Stuetzner b. 26 Aug 1874; bp. 16 Jul 1909; m. —— Wiedemann; k. in air raid Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 13 Feb 1945 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 183; Schade-Krause; FHL Microfilm 245299, 1930 Census)

Otto Weber b. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 18 Dec 1898; son of Karl Gustav Weber and Auguste Schubert; bp. 29 Jun 1910; conf. 29 Jun 1910; ord. deacon; ord. teacher 12 Sep 1920; ord. priest 3 Mar 1929; missing as of 10 Dec 1948 (CHL, LR 2328 22, no. 156; CHL 2458, Form 42 FP, Pt. 37, 748)

Max Zöllner bp. 1916; d. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 18 Oct 1940, age 65 (Sonntagsgruss, no. 45, 8 Dec 1940 n.p.)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Leo Van Gray, diary, 1939; private collection.

[3] Annelies Höhle and Ursula Höhle Schlüter, “Those Are Just Little Things,” in Behind the Iron Curtain: Recollections of Latter-day Saints in Eastern Germany, ed. Garold N. Davis and Norma S. Davis (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 2000), 264. Because the records of the East German Mission show the Altstadt Branch meeting at Königsbrückerstrasse 62 as early as September 1, 1938, the new construction mentioned by Sister Höhle was actually a renovation, and Leo Van Gray’s record corroborates the activity.

[4] Herbert Schroeter, interview by the author, Bountiful, Utah, June 21, 2007.

[5] Harald Schade, interview by the author in German, Burg Stargard, Germany, June 10, 2007; unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[6] Edith Schade Krause, interview by the author in German, Prenzlau, Germany, August 18, 2006.

[7] Dieter Duennebeil, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, May 4, 2006.

[8] Höhle and Schlüter, “Those Are Just Little Things,” 265–66.

[9] Hellmuth Günther Dahms, “Der Weltanschauungskrieg gegen die Sowjetunion,” in Der 2. Weltkrieg:Bilder Daten Dokumente (Gütersloh, Germany: Bertelsmann, 1968), 397. Total losses of the German Sixth Army may have been as high as 295,000 men.

[10] East German Mission, “Directory of Meeting Places,” (unpublished manuscript, 1943); private collection.

[11] Karin Gräber Adam, interview by the author, Bountiful, Utah, April 18, 2007.

[12] David Irving, The Destruction of Dresden (London: William Kimber, 1963), 76.

[13] Ibid., 138–39.

[14] Ibid., 146.

[15] Ibid. The bomber in question had arrived ten minutes behind schedule and was therefore “alone.”

[16] Ibid., 154.

[17] Ibid., 152.

[18] See the description of this precaution in the introduction.

[19] Dorothea Speth Condie, “Let’s Follow Dad—He Holds the Priesthood,” in Behind the Iron Curtain, 33.

[20] Ibid., 35. The detail on the street names was provided by Dorothea’s sister, Gisela Speth Kehaya, in a letter to the author on July 15, 2008.

[21] Christa Gräber Zander, interview by the author, West Jordan, Utah, March 2, 2007.

[22] Condie, “Let’s Follow Dad—He Holds the Priesthood,” 237.

[23] Irving, Destruction of Dresden, 189

[24] Höhle, “Those Are Just Little Things,” 264. In reality, one other sister in the branch was killed that night.

[25] Condie, “Let’s Follow Dad—He Holds the Priesthood,” 37.