Danzig Branch, Danzig District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 205-17.

As the only branch of the LDS Church in the German missions that was not in Germany itself, the Danzig Branch was a novelty. The fact that the branch even continued to exist was a blessing, given the adjustments made to the German borders after World War I. The territory to the west and the south of the Free City of Danzig had been ceded to Poland, and the majority of the ethnic Germans living there had moved to German states to the east and the west.[1]

| Danzig Branch[2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 7 |

| Priests | 3 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 5 |

| Other Adult Males | 22 |

| Adult Females | 42 |

| Male Children | 4 |

| Female Children | 11 |

| Total | 97 |

The Danzig Branch was not very large but still the largest of the three in the Danzig District. With ninety-seven members, the branch was strong enough to support all of the auxiliaries and programs of the Church. As was often the case in German branches, the largest group was that of adult females (43 percent in this branch).

Hedwig Biereichel (born 1915) recalled meeting in several different schools during the 1930s, but the branch meetings took place at Damm 7 in the city’s District IV when the war started. There were thirty to forty members in attendance at that time.[3]

The family of Hermann and Paula Lingmann lived on a small Baltic island near Danzig and operated a modest store there. Brother Lingmann was pressured to join the Nazi Party but declined. His daughter, Esther (born 1924), recalled the following incident:

One day, the Jungvolk marched in front of our store, stopped there, and started singing “Haut die Juden an die Wand” [throw the Jews against the wall]. . . . My father stepped outside, asked who the leader was, and when one boy stepped to the front, my father slapped him. He shouldn’t have done that because the next day they did it again, but this time the police were there . . . waiting for my dad to come outside so they could arrest him. . . . Later on, the main leader of the party came and told my father sincerely that he would have to join the party or he would lose his customers.[4]

In 1939, Esther Lingmann was required to serve her Pflichtjahr for the government and was assigned as a nanny in a family with five children. She was only fifteen and looked much younger. Her mother accompanied her to the home where she was assigned to work. When the lady of house saw her, she said, “I have five children, and you’re too young to help me!” Later, Esther was assigned to work with a different family, where she was allowed to leave at 4:00 p.m. each day. She was close enough to home to spend every night with her own family. Soon thereafter, she found employment in the Danzig shipyards.

Margarete Damasch Eichler (born 1906) was a young mother and the wife of an unemployed laborer as World War II approached. In her autobiography, she wrote of the political conditions in Danzig in the late 1930s: “There were many debates about [Hitler] in Danzig. About three-quarters of the population of our Free City of Danzig were against him.”[5] Nevertheless, Hitler enjoyed a sizable following in Danzig, and Richard Müller (born 1926) recalled seeing and hearing many groups of uniformed Nazi Party members and Hitler Youth. “Later on, the Nazi movement in Danzig became stronger and stronger,” he explained.[6]

The German army invaded Poland on Friday, September 1, 1939. Heino Müller (born 1922) recalled the day quite clearly:

We stood on the tops of our apartment houses and watched when the [German] dive-bombers attacked the Polish. . . . The Polish put some guns into a post office building, and a real fight broke out. It went on for two or three days before the Polish gave up and came out. . . . It was terrible! We didn’t like it at all.[7]

The campaign lasted only three weeks and peace was restored. After nearly two decades as a Free City, Danzig was again part of the German Reich; all of the territory lost by Germany to Poland through the 1919 Treaty of Versailles was regained, and Adolf Hitler soon went there to celebrate the victory. To accommodate the Führer, local officials expanded a large hotel, but the expansion required the demolition of the Eichler home on Jopengasse. Sister Eichler unhappily spent a great deal of time searching for a new apartment. On the other hand, her husband, Ernst, had work again because the German war effort required many additional laborers in the Danzig harbor.[8]

The Müller family during the war: (top from left) sons Heino, Richard, and Rudi; (bottom) daughter Wilma and parents Katharina and Wilhelm (W. Fassmann)

The Müller family during the war: (top from left) sons Heino, Richard, and Rudi; (bottom) daughter Wilma and parents Katharina and Wilhelm (W. Fassmann)

“I saw Hitler in person twice,” explained Richard Müller, “when he came to Danzig after the Polish campaign in September 1939 and in about 1942 or 1943, when he came to inspect submarine construction.” The organizers of those visits saw to it that throngs of schoolchildren were lined up along the route to cheer Germany’s Führer as he drove by.

Lilly Eichler (born 1932) turned eight in 1940 and was baptized in the Baltic Sea. “We didn’t have to do it in secret. There was no problem,” she later explained.[9]

Charlotte Schulz Bever (born 1922) lived with her family in Zoppot, a small town about eight miles west of Danzig. She later described the effort required to attend Church meetings:

From Zoppot to Danzig we had to take the train, and then we walked to the branch meetinghouse in the city center. This took us over one hour since we also had to walk to the train station [in Zoppot] and then again from the train station in Danzig to the branch rooms, which was a fifteen-minute walk. We could only attend church on fast Sunday since we did not have much money.[10]

Because they could not attend church meetings more than about once a month, Charlotte’s mother worked hard to keep their faith alive in the home. As Charlotte later explained:

My father did not have work but my mother always paid her tithing faithfully. She knew the Book of Mormon very well. During the winter time, when we were sitting with our backs to the oven, my mom and I sang songs out of the old hymnbook.

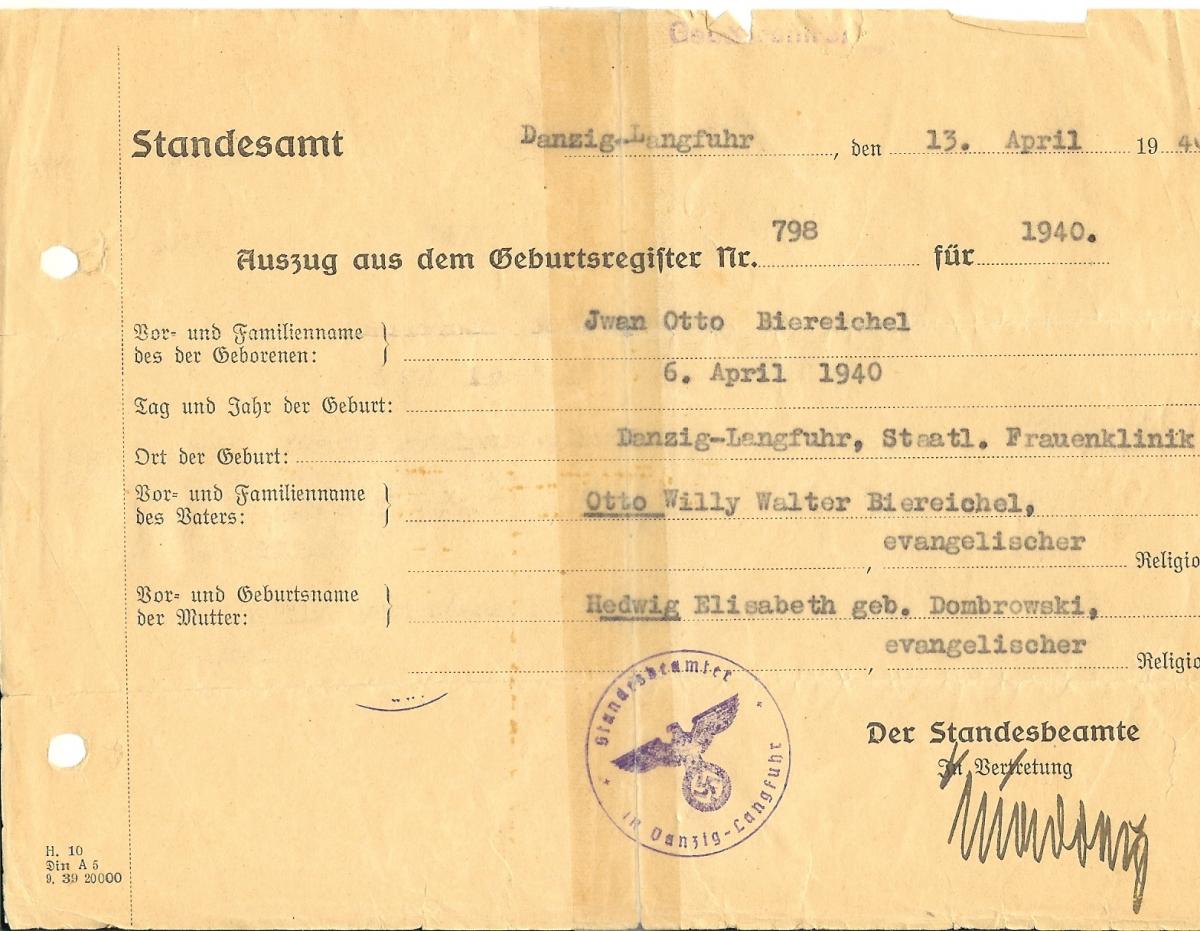

Hedwig Biereichel’s husband was not a member of the Church, but in her opinion, “he was a better man than many of the members.” He was drafted into the German air force ground crew soon after the war began. Their second child, a son, was born on April 6, 1940, and Sister Biereichel gave him the name Ivan, as she described years later: “My husband was gone when [Ivan] was born and was really angry when he came home and found out what name I had chosen.” The civil registrar tried to talk her out of using a Russian name for her son, but she insisted, stating later that she had been inspired to name him “Ivan” (but she had no idea why). Later, she learned how the selection of her son’s given name actually saved her life (see below).

The birth certificate of Iwan Biereichel in 1940. The letter J represents I in the name of the child, and the civil registrar erroneously listed Hedwig’s religion as evangelisch (Protestant). (I. Biereichel)

The birth certificate of Iwan Biereichel in 1940. The letter J represents I in the name of the child, and the civil registrar erroneously listed Hedwig’s religion as evangelisch (Protestant). (I. Biereichel)

The meeting rooms at Damm 7 were apparently given up during the early years of the war because Hedwig Biereichel recalled meeting at Guttemplerloge later on. Unfortunately, the calamities of war followed them there: “Then everything was bombed out. . . . All the priesthood leaders were gone and nobody could bless the sacrament anymore. Relief Society was still held [for a while]. We did not see each other [much] anymore.”

The Danzig Branch on Mother’s Day, 1939 (L. Eichler Love)

The Danzig Branch on Mother’s Day, 1939 (L. Eichler Love)

The records of the East German Mission indicate that at least one more move had occurred by 1943—to the address of An der großen Ölmühle 1. Richard Müller recalled that the building was used by some kind of antialcoholism association during the week and by the branch on Sundays. The structure did not survive the fall of Danzig in 1945.

In mid-war, Rose and Lilly Eichler were sent to the town of Wobesde, near the Baltic Sea about sixty-five miles west of Danzig. There they were safe from the air raids over Danzig and were privileged to live with a fine Latter-day Saint family—the Lawrenzes. The girls went to school and church in Wobesde and felt quite at home. When the Eichler family moved to a Danzig suburb, Lilly returned home to them. Rose stayed in Wobesde because she was nearing the end of her public school tenure. She remained there until the late summer of 1945.[11]

An electrician by trade, Heino Müller worked in the Danzig shipyards in the construction of submarines. This critical war industry was Heino’s ticket to civilian life. He reported to the draft board in 1940 for an examination but was exempted from military service. During the war, he was often the only young man attending church in the Danzig Branch. During these years, he also courted former missionary Irmgard Gottschalk of the Breslau Center Branch, and they were married on March 1, 1944.

Wilma Müller was attending a business school when the war broke out in 1939. She then found a job as a secretary but was paid less than 100 marks a month. Her father suggested that she join his company—the Kafemann Company at the Danzig shipyards. She made the transition and was paid more than twice the previous amount. She was still working there in late 1942 when she became engaged to Emil Voge. They were married on October 20, 1942, and she was ready to leave Danzig to live in Lauenburg, Pomerania, but needed permission to do so. As she explained, “The law stated that nobody could walk away from the job unless they had a replacement.” Her sister-in-law Irmgard was willing to assume her job, and Wilma was allowed to move to Lauenburg.[12]

All over Germany and Austria, individual Saints had to decide whether to support the Nazi Party or to avoid the issue. Most of the members of the Damasch and Eichler families were not in favor of Hitler, but a few members of the Danzig Branch joined the Nazi Party after Germany conquered the Free City in 1939. In fact, in early 1942, one of them denounced Margarete’s husband, Ernst Eichler, to the Gestapo as a traitor. According to Sister Eichler’s autobiography,

Ernst was told the police had found out that he worked for the Americans. . . . He denied the charges and asked for an explanation. He was then cross-examined about his Boy Scout activities. . . . Ernst tried to explain that he was in charge of a pathfinder program. . . . [The police] intentionally tried to confuse him and catch him in a contradiction. [author: source?]

During the interrogation, Brother Eichler explained his patriotism based on the Church’s Twelfth Article of Faith. He also explained his loyalty to Jesus Christ and unabashedly defended Christ as a Jew. After three hours, he was released and instructed simply to avoid the use of the term “Boy Scout.”[13]

Lilly Eichler recalled how her father agonized about the political and military situation in the early war years. He would listen to the government propaganda in the radio broadcasts and pace across the floor. “He was just listening and shaking his head. He didn’t say a word, [but] he was totally against it,” Lilly recalled. As a youngster, she saw other people hanging out large swastika flags, and she thought that was exciting. “Why can’t we have a flag?” she asked her mother. “Your father doesn’t want that,” was the response. Finally, Lilly was allowed to have “one of those tiny flags that you hold in your hand.”

Harald Damasch (born 1905) was employed in an aircraft factory in Dessau in early 1942 when he carelessly mentioned to colleagues that Germany had little chance of winning a war against both the Soviet Union and the United States. He was arrested soon thereafter and spent several months in a concentration camp. His health was seriously damaged, and after he was released, he told his wife that he had been poisoned. He died shortly after returning to Danzig.[14]

Hedwig Biereichel and her son, Iwan, in 1941 (H. Biereichel)

Hedwig Biereichel and her son, Iwan, in 1941 (H. Biereichel)

According to Richard Müller, his father responded to the pressure of the Nazi Party in a very ingenious way. Instead of becoming a Nazi, he joined another patriotic organization called the Reichskolonialbund—a league promoting the heritage of the German colonial territories in Africa before 1918. All Wilhelm Müller had to do to appear active in the league was distribute literature sent to him from the league headquarters in Berlin. This allowed him to keep the local Nazis at bay.

Hedwig Biereichel’s husband served in the army in Berlin, northeast Germany, Paris, and Italy, where he was captured in 1943 by the Americans. Hedwig did not see him again until 1946. At home in Danzig, Sister Biereichel was not happy with Hitler’s government or the Nazi Party. She later told this story:

I gave food to Russian prisoners working on the trash collection detail. I hid the food in my trash can. Sometimes I went outside to them and gave them the packages that I made so that they could hide it. I did it every week. I did enough things in contradiction to Hitler’s instructions that they should have shot me fifty times. Somebody even reported me because of my son’s name (Ivan).

Somehow, she always had a plausible excuse for her behavior.

During the war, Sister Biereichel attended church regularly with her children. According to her recollection, the Church suffered no persecution at the hands of the government, but officials attended the meetings at times, and hymns featuring the words “Zion” and “Israel” were not to be sung.

Toward the end of 1942, Wilma Müller Voge went to live with her new husband in the town of Lauenburg (now Labes, Poland), two hours west of Danzig and an hour south of Wobesde. Emil Voge was the president of the Danzig District. Because there was no branch in Lauenburg, the Voge family officially belonged to the Wobesde Branch (fifty-five miles to the west). However, it was more convenient for them to attend the Danzig Branch. Emil Voge, a master tailor, was a supervisor in the Zeek Company, which made military uniforms. Wilma later wrote about her service as a member of the Church in their isolated location in Lauenburg:

When I left Danzig I had to be released from my church calling. We both wondered what the Lord wanted me to do in Lauenburg. After a few days I received a letter from the [mission] headquarters in Berlin calling me to be the historical and financial secretary for the Danzig District. They said that the calling had never been given to a sister before but because so many brethren were fighting in the war, they wanted me to do it. . . . We spent so much time together doing the Lord’s work. We traveled together [to visit the branches] until two weeks before [our son] was born [on November 17, 1943]. [author: source?]

When air raids began to strike Danzig on a regular basis, the residents found themselves spending more and more time in bomb shelters and basements. As was the case throughout Germany, if an alarm lasted until after midnight, the start of school the next morning was delayed by one hour. Years later, Lilly Eichler recalled the importance of the timing: “Sometimes [the alarms] ended five minutes before twelve, and we were mad because we were deprived of that extra hour of sleep.” During air raids, the Eichlers usually went to the basement of a large government building nearby (“It was a nasty place!”). Often, Lilly’s father did not go there with the family, being too far from home.

Many of the antiaircraft crews around Danzig consisted of schoolboys. Richard Müller was one of those boys in 1943 at the age of sixteen. With his friends, he was sometimes stationed at a battery for several days at a time. During that time, teachers would come from the school to give the boys their lessons in mathematics, chemistry, and other subjects. A year later, Richard served in the Reichsarbeitsdienst, but only for six weeks because his draft notice arrived on May 15, 1944.

By mid-September 1944, Richard Müller had finished his basic training in Munster near Hannover and was transferred into an Officer Candidate School. He had no desire to become an officer, but his father wrote to advise him to stay in such a program as long as possible, in order to stay out of combat zones. Wilhelm Mueller also advised his son regarding standards of personal conduct, “If you keep the Word of Wisdom, if you keep yourself morally clean, nothing [bad] will happen to you.” One very pleasant aspect of this training period was that Richard was able to attend church meetings (“at least Sunday School,” he explained) in the nearby Celle Branch for five months.[15]

When his draft notice arrived in September 1944, Heino Müller realized that the Reich now needed him more as a sailor than as an electrician. Because he knew submarines inside and out, he assumed that he would be assigned to serve aboard one of those vessels. However, one day, a navy officer announced to the recruits, “I have the honor to hand you over to the Waffen-SS.” Heino Mueller had become a member of the elite combat troops under the personal command of Heinrich Himmler—one of the top men in Hitler’s Germany.

Riding the train south to Prague for basic training, Heino prayed to his Heavenly Father, “No matter what happens to me, help me that I don’t have to hurt anybody or kill anybody!” His training was brief, a mere five shots from a rifle on the firing range. “The idea of these German troops being so well trained was a fairy tale by that stage of the war,” he later explained. By October, he was a member of the famous SS Hohenstaufen Division, fighting the Americans who were advancing toward Germany. Assigned to the signal corps, Heino was in the thick of the fighting in Belgium when the Germans unleashed their final attack—the Ardennes Offensive that became known as the Battle of the Bulge. He escaped death on several occasions, such as the time when a huge piece of shrapnel landed at his feet: “It was about a foot long with sharp edges. If that had hit me, that would have been the end of me. It landed right at my feet.”

By the time Heino Müller’s battalion was pulled from the front at the Bulge, only one officer and about forty men were left of the six hundred who entered the battle. After a few weeks of rest in Germany, they were shipped to Hungary, where they attacked Soviet positions. Once during heavy artillery fire, Heino moved quickly from one crater to another, theorizing that the enemy changed his trajectory with every shot, such that the safest place would be where the last shell landed. Fortunately, his theory was correct.

In the first few weeks of 1945, the members of the Danzig Branch discussed what they should do as the Red Army approached the city. Branch president Willy Horn had received a letter from Paul Langheinrich (second counselor to the mission leader in Berlin) encouraging the Saints to evacuate the city right away and head west (which some branch members had already done). From Sister Eichler’s recollection:

When Brother Horn finished reading the letter, . . . he [said that he] thought that Heavenly Father would protect us from all the terrors of the war, if we had enough faith in him. . . . He asked us to form a circle with the chairs. . . . We all knelt by the chairs, and Brother Horn offered a very humble and long prayer. When he was finished, he . . . told us to trust in the Lord and to return home with peace in our hearts—all would be well. A week later we heard that some of the members did not listen to his counsel but . . . left for the west. . . . Those of us who stayed behind experienced much agony and hardship.[16]

It would seem that Willy Horn’s inspiration may have been in error on that occasion. In reality, those who rejected his recommendation and left the city right away were spared great hardship. Those who stayed suffered. There were disagreements on the issue even between spouses. For example, Brother Eichler decided that his family should remain in Danzig, though his wife did not agree.

Hermann Lingmann was required by the government to stay and defend Danzig, and his wife decided to stay with him. Thus only their daughter, Esther, boarded a ship in early March for the voyage to the west and safety from the invaders. Sitting in a coal hold of the ship, Esther heard odd sounds, and the lights went out. It was announced that the engine was having mechanical problems. Then word went around that the message was not true; the ship had struck a mine. A while later the ship hit another mine, and Esther went up on deck. There she found the sailors wearing life jackets—apparently ready to abandon their ship, which by then was listing to one side. Fortunately, they were close to a port, and another ship came alongside to rescue them. Eventually, Esther reached Wilhelmshaven in western Germany and was taken in by a local family for the next two weeks.

Hedwig Biereichel was still in Danzig when the Red Army entered the city in the spring of 1945. Her husband was already a prisoner of the Americans, and she had recently given birth to her third child. She was fortunate to be taken into her parents’ home, but no place was safe after Danzig surrendered, especially for a pretty woman thirty years of age. As she later recalled,

Once a soldier wanted to take me, and my father got in the way. He pointed his pistol at my father’s chest and said, “If the woman doesn’t come with me in five minutes, I’ll kill the father.” I was ready to go, rather than have my father killed, when an officer came through the door. Instantly, the soldier put his pistol away and denied that he had threatened us. The officer ordered the soldier out and promised us that this would not happen again. I was ready to kiss the officer’s feet. I owed him my life.

In March 1945, the Soviet army entered Lauenburg. Wilma Voge’s first son, Wilfried, was sixteen months old, and she was six months pregnant. When an enemy soldier found that Emil Voge had a paper with a swastika seal, the soldier decided that Emil was a Nazi and should be executed. A feisty young mother, Wilma jumped in front of her husband and declared, “You kill me and the boy first!” The shocked soldier left the house.

One evening, Russian soldiers entered the home Wilma was staying in and uttered the terrifying command, “Frau, komm!” A young officer intervened and sent the soldiers away. He returned on several occasions to save Wilma and her sons again, such as the night when several homes in the Voge neighborhood caught fire. The homes were built in rows and might all have burned down, but Wilma’s protector gathered several other Russian soldiers and tore down part of the adjoining house to form a firebreak. Later, Wilma wrote, “We knew that the Lord had sent [that soldier] to protect us.”

Unfortunately, their protector was not around when other soldiers came to take Emil Voge prisoner. As he was led away, he told his wife, “Our lives are in God’s hands.”

Ernst Eichler (born 1937) remembered the last few days before the invaders conquered Danzig. His family lived in a small suburb on the outskirts of town, and German soldiers fought a hopeless defensive campaign against the Soviet onslaught:

Every house except ours was destroyed. Ours was damaged by our own military. The Russians were advancing fast, and the German artillery lowered their guns so low, they shot right through the roof of our house. When the Russians came [closer], my dad would watch out of the window, he could tell they were coming. And we would go down in our shelter and hide. We could actually see the Russian army from our house.[17]

When the German defense of Danzig proved fruitless and the invaders entered the Eichlers’ neighborhood, the family huddled in a hole Brother Eichler had dug beneath the basement. Ernst recalled the events of March 26, 1945:

We heard soldiers walking around upstairs, you could hear their boots on the floor. We didn’t hear anybody coming down, but my dad failed to engineer this bomb shelter very good; he didn’t put ventilation in it. After about half an hour or so, we were running out of oxygen. And my dad carefully pushed the trap door up to let air in, and as soon as he got up, a rifle was coming down there. So somebody came down into the cellar looking but didn’t know we were down there. But when my dad pushed the door up, the soldier made us all come out. My dad was taken prisoner. And then we had to leave. They forced us out.

Ernst Eichler was the fourth of five children. Those children were old enough at the end of the war to contribute to the effort of collecting food for the family. During the final months of the war, Ernst and his elder sister, Ellen, were sent by their mother to a farmer just outside of town. Their errand was to get some potatoes. Ernst told this story:

We were heading on home carrying a bag of potatoes—there probably wasn’t even ten pounds in it. My sister and I each had one hand on it; she was three years older than me. Then the air-raid sirens went off, and we wanted to get to a shelter. We saw a Russian dive-bomber drop his bombs, then he swooped down right at us with a machine gun and shot the bag of potatoes out of our hands. [Ellen] dove into the bushes, and I did too, and then I lost her. I didn’t know where she was. The potatoes were rolling all over the street. And I was crying, a seven-year-old boy, and I kept calling my sister, I said; “Ellen! Ellen!” And she wouldn’t answer. She was in the bushes just a few feet from me. Finally she said, “Be quiet! They’ll hear us and come back and shoot at us again!”

During the next few months, Hedwig Biereichel came to understand why she had been inspired to name her son Ivan. On many occasions when she attempted to procure food for her children, she ran into obstacles. When she displayed the boy’s birth certificate, those obstacles were removed from her path. The Soviets and the Polish apparently assumed that she had chosen that name because she was a communist sympathizer.

In the summer of 1945, Wilma Voge gave birth to her second son, Nephi Martin, in the house that nearly burned down. Fortunately, Emil had been released from a work detail just a few miles away and made it home for the event. There was no hospital nearby, and Wilma was assisted by a nurse who apparently did not observe proper hygiene practices. Wilma bled profusely and developed a fever. “How I ever lived through this I will never know,” she later wrote.

By the time Richard Müller finished officer’s candidate school in March 1945, thirty of the fifty-six men had been eliminated from the program. Following successful completion of the course, he was sent to Döbeln in Saxony for training with rocket artillery. After three weeks in Döbeln, he was sent back to Munster. As a junior officer, he was given command of thirty men armed with bazookas. Their orders were to stop British tanks advancing along the Hamburg-Hanover Autobahn. While entrenched along the Autobahn, they had a curious experience:

Some women SS guards from the Bergen-Belsen Concentration Camp were marching some female prisoners down the road. The prisoners looked terrible. When the guards saw my thirty men, one of them said, “Here is my chance to get some sex again!” and she started to take off her clothes. I was only eighteen and a half and had never seen a naked woman before. My knees went weak, and I prayed to my Heavenly Father: “Please, please help me!” Then I drew my pistol and threatened my men: “If any of you get involved with these women, I’ll shoot you!” Of course, I had no intention to shoot them. Here were these well-fed SS women taking off their clothes, and over there were the prisoners looking like walking skeletons. Luckily, one of the women yelled, “Come on, we’ve got to get out of here!”

A few days later, Richard Müller’s unit was caught between the invading Americans and the retreating Germans. As his unit fell apart in the confusion, he and his friend ran for the forest, trying to work their way to a safer environment. By April 27, they had surrendered to British soldiers, were taken to Belgium, and put to work. On September 23, Richard turned nineteen and in accordance to camp tradition, was allowed to eat all he wanted. He threw everything up a half hour later, because “my stomach just couldn’t take it.”

By April 1945, Heino Müller’s Waffen-SS unit had retreated through Yugoslavia to Austria, where they encountered British troops coming from Italy. Heino knew that he was fortunate to surrender to the British, who understood that Waffen-SS soldiers were not the men responsible for the deaths of Soviet POWs or inmates of concentration camps. “That was the best thing that could have happened to me,” he later explained. “If the Russians had captured us, I don’t know if I could have gotten out alive.”

Under first Soviet and then Polish occupation authorities, some Germans in Danzig were evicted while others were forced to stay. The Danzig Branch was torn apart in this confusion. For example, Margarete Eichler and her children became refugees for the next six months, subject to constant danger and privation. Sister Eichler later recorded her first thoughts in this new and insecure stage of life:

We walked for hours and everybody was getting tired. We had not eaten anything for almost 24 hours. I thought of the pioneers [in the United States] and likened our situation to theirs, although they had to leave for their religious beliefs. They, too, had to leave many of their belongings behind, pushing heavy carts on uneven dirt roads into an unknown future. Heavenly Father comforted them and blessed them to make their load seem lighter. I hoped that Heavenly Father would help us too, and that all would be well in the end.[18]

A few days later, they escaped from a burning house but lost much of what little they carried with them, including all of Brother Eichler’s family history documents. Sister Eichler’s Book of Mormon was spared. Indeed, a few weeks later, an angry Red Army soldier took that book from Sister Eichler and tried to tear it up, yelling “Hitler book! Hitler book!” Somehow, he was unable to destroy the book, and she concluded that an invisible force had prevented him from damaging her precious volume.[19] Braving conditions severe enough to crush weaker women, Margarete somehow kept her children and her mother-in-law (weakened by illness) alive and moving away from Danzig.[20]

As the Eichlers headed south, they left notes at every Red Cross station, seeking information about Brother Eichler. On one occasion, a man saw the note they posted and said that he knew where Brother Eichler was. It turned out that he had been shipped to the Soviet Union as a prisoner and then was released because he was very ill and his captors thought that he was dying. Sister Eichler found her husband in a squalid field hospital, covered with newspapers and lying among corpses. As soon as he had recovered sufficiently, they headed west to Berlin and south to Saxony. In October 1945, they arrived at the Latter-day Saint colony at Wolfsgrün near Zwickau.

After Charlotte Schulz Bever was forced to leave Danzig, she headed west to Germany. She settled in Schwerin, north of Berlin, where there was no branch at the time. Fortunately, missionaries located her there soon after her arrival, and a branch was established.

In October 1945, the Voges were evicted from their home, and Wilma was subjected to additional suffering. She was bedridden the entire winter. With the arrival of spring, she was ready to leave what had become Poland. During the last trial, the evacuation to Germany, there was one last tragedy at the railroad station. She wrote this description years later:

As we waited I was busy changing Nephi. We noticed that Wilfried had disappeared. I got almost hysterical, blamed my poor husband for not watching him. It was so bad, because the train was supposed to come shortly and we had to go with or without Wilfried. I was running, asking different people if they had seen a little boy. One lady said that she had seen a little boy with a book under his arm a few blocks away. Thank God, we found him before the train came. Another terrible thing happened. As we looked for Wilfried, someone took my husband’s briefcase with all his genealogy. I thought my husband had lost his mind that day. I don’t think he had ever recovered from the loss as long as he lived. Here he had lost many years work. Only God knows what happened to his records.

In the summer of 1946, the Voge family arrived in Langen near Frankfurt am Main and became members of the growing Latter-day Saint refugee colony there.

Shortly after the Eichlers arrived at Wolfsgrün, the mission leaders in Berlin asked Brother Eichler if he would return to Danzig to help the remaining Saints evacuate that city and travel west to Germany. He reluctantly accepted the assignment (having nearly died just months before) and returned to Danzig. A trip that normally would take one day took three weeks.

Hedwig Biereichel remembered how Brother Eichler came back to rescue the twenty-two Latter-day Saints still in Danzig. At the time, only two priesthood holders were still in Danzig, Brother Horn and Brother Kossin, and meetings were being held in the Horn home. Sister Biereichel told this story:

The brethren sent me to get permission to leave Danzig and I used my lists of [Church] members to get permission. I told them that all the people (22 of them) were my family. We got the permission to go second class on the train. We left on a train on November 21, 1945—our seats were cushioned. Our railroad trip took us across the Oder River bridge at Küstrin. There was a Russian officer in every car so that the Polish would not rob us blind. We were put into the concentration camp at Dora-Mittelbau near Nordhausen. They had changed it into a refugee camp. . . . Later we went to the mission office in Berlin, and from there to Wolfsgrün.

Hedwig Biereichel later made her way to West Germany and was united with her husband in 1946.

The eldest Eichler daughters, Ruth and Rose, eventually joined their parents and siblings in Wolfsgrün, and the family was complete again. Their parents’ agonizing wait was finally over.

Hermann Lingmann was captured by the Red Army but somehow managed to escape during the summer of 1945 and make his way to Glauchau. Soon thereafter, he received a telegram from his wife, who had been safely evacuated from Danzig. He found her and brought her to Glauchau, where they were given a nice apartment by city officials.

Richard Mueller was released from his POW status in Belgium in mid-December 1945 and made his way directly to Celle. After six weeks there, he crossed the border into the Soviet Occupation Zone and found his parents living in a small town near Wismar in Mecklenburg. They were attending church in Rostock. From there, they joined the large colony of Latter-day Saint refugees assembled at Langen in the American occupation zone.

Richard Müller, fourth from right, as a new Wehrmacht recruit (R. Mueller)

Richard Müller, fourth from right, as a new Wehrmacht recruit (R. Mueller)

As a POW, Heino Müller was moved by his British captors to Northern Italy, where he worked as an electrician. During his incarceration, he and his comrades were told that there was no value in returning to Germany yet because in the ruined economy of the defeated nation, there would be no employment for them. He was finally released in June 1947 and made his way to Langen, where he joined his wife in the Latter-day Saint refugee colony. Regarding his short military career, he later made these comments:

Sometimes people have problems because of the war. I never had any problems because I never did anything I had to regret. The Lord probably listened to me and arranged it so that I did not have to hurt anybody, shoot anybody, though I had the chance to do that. . . . I trusted in the Lord. I knew he would help me. I was so sure of it.

Looking back on the war years in Danzig, Lilly Eichler recalled that her family lived in a kind of cocoon. They concentrated on family and church and tried to forget the difficult things happening around them.

Richard Müller later saw clearly how the Lord had blessed his family: “There was hardly any family in Germany who had three sons in uniform and all of them came home safely. None of the three of us got even a scratch.”

For years, the Lingmann family held onto their hope that Heinz would return. Missing in action in Italy since April 1945, he was officially declared dead in 1960. Given the terrible sufferings of the members of the Danzig Branch, the fact that only nine of them are known to have died during the war is remarkable.

Wilhelmine and Wilhelm Ruth. Sister Ruth died in childbirth in 1943. [K, Ruth]

Wilhelmine and Wilhelm Ruth. Sister Ruth died in childbirth in 1943. [K, Ruth]

In Memoriam

The following members of the Danzig Branch did not survive World War II:

Wilhelmine Henriette Braatz b. Cetschau, Danzig, Westpreussen, Preussen 7 Oct 1899; dau. of Johann Edward Julius Braatz and Auguste Catharine Rieck; bp. Free City of Danzig 9 Aug 1934; m. Danzig 11 Aug 1934, Wilhelm Herbert Ruth; 2 children; d. childbirth Danzig 21 Aug 1943; bur. Danzig (Kurt Ruth)

Bruno Erich Damasch b. Danzig, Westpreussen, Preussen 3 Sep 1896; son of Georg Damasch and Johanna Olga Detloff; bp. 9 Sep 1904; m. 5 Jun 1930, Frieda M. Baumgart; 2m. 25 Oct 1941, Herta—; MIA Danzig 1 Mar 1945 (IGI; www.volkbund.de)

Erich Harald Damasch b. Danzig, Westpreussen, Preussen 29 Sep 1905; son of Georg Damasch and Johanna Olga Detloff; bp. 11 Jul 1916; m. 27 Mar 1937; d. ill effects of concentration camp confinement Danzig Free City 12 Dec 1944 (M. Eichler; IGI)

Marie Amalie Friederike Enseleit b. Danzig, Westpreussen, Preussen 7 Dec 1854; dau. of Johann Enseleit and Juliana Henriette Wilhelmine Henriette Preuss; bp. 31 Oct 1904; m. Danzig 27 Oct 1876, Louis Theodor Müller; 10 children; d. Danzig Free City 25 Feb 1940 (Sonntagsstern, No. 17, 26 May 1940, n.p.; IGI)

Charlotte Marie Haeldtke b. Danzig, Westpreussen, Preussen 20 Aug 1894; dau. of Richard Wilhelm Haeldtke and Clara Franziska Klose; bp. Aug 1920; m. Danzig Free City Sep 1919, Hermann Karl Wolf; 2 children; d. starvation Danzig Aug 1945 (IGI)

Robert A M Lau b. Danzig, Westpreussen, Preussen Feb 1869; son of Friedrich Lau and Augusta Rohr; bp. 20 May 1907; ord. teacher; m. Julianne Krauser; d. starvation Jun or Jul 1945 (FHL Microfilm 271385, 1930/

Johannes Lingmann b. Schneidemühl, Posen, Preussen 18 May 1921; son of Herman August Lingmann and Paula Elisabeth Weller; bp. 29 Sep 1929; private; d. Apr 1945; bur. Costermano, Italy (IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Maria Katharina Otto b. Weichselmünde, Danzig, Westpreussen, Preussen 20 Apr 1864; dau. of Georg Otto and Katharina Cornelia Goergens; bp. 14 Sep 1924; m. Weichselmünde 18 Nov 1883, Johann Gottlieb Kossin; 12 children; d. lung disease Danzig Free City 21 Sep 1939 (Stern No. 20, 15 Oct 1939, pg. 323; FHL Microfilm 271381, 1930/

Arthur Otto Sawatzke b. Danzig, Westpreussen, Preussen 27 Aug 1897 or 27 Sep 1899; son of Carl Otto Sawatzke and Minne Renate Holstein; bp. 4 or 10 Aug 1927; ord. teacher; m. Schönau, Danzig Free City 2 Aug 1927, Gertrud Marie Sawatzke; 2 or 4 children; d. as forced laborer Russia 15 Aug 1945 or 1946 (Sawatzke; IGI; FHL Microfilm 245257, 1930/

Johannes Hermann Wolf b. Danzig Free City 1 Jun 1922; son of Hermann Karl Wolf and Charlotte Maria Haeldtke; bp. 1 Jun 1930; k. in battle Russia 24 Jul 1944 (H. Müller; IGI)

Notes

[1] The modern Polish name of Danzig is Gdansk.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[3] Hedwig Dombrowska Biereichel, interview by the author in German, Hannover, Germany, August 6, 2006. Unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] Esther Lingmann Vilart, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, April 24, 2008. Unless otherwise noted, transcript or audio version of the interview in the author’s collection.

[5] Margarete Damasch Eichler, autobiography (unpublished, 1999), 57; private collection.

[6] Richard Müller, interview by Michael Corley, Bountiful, Utah, March 14, 2008.

[7] Heino Müller, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, February 29, 2008.

[8] Rose Eichler Wood, “Biography of Rose Wood” (unpublished), 8–9; private collection.

[9] Lilly Eichler Love, telephone interview by Jennifer Heckmann, April 2, 2008.

[10] Charlotte Schulz Bever, interview by the author in German, Schwerin, Germany, June 11, 2007.

[11] See the Wobesde Branch chapter for more about Rose’s experiences in 1945.

[12] Wilma Müller Voge Taylor, “Life Story” (unpublished autobiography, 1985); private collection.

[13] Margarete Damasch Eichler, autobiography, 70–71. The Boy Scout program in Germany was dissolved by government order in 1934. The twelfth article of faith reads as follows: “We believe in being subject to kings, presidents, rulers, and magistrates, in obeying, honoring, and sustaining the law.”

[14] Eichler, autobiography, 60–61.

[15] The Celle Branch was part of the Hanover District of the West German Mission. No other soldier of the East German Mission is known to have had a similar opportunity. Most were totally isolated from the Church while away from home.

[16] Eichler, autobiography, 80–81.

[17] Ernst Eichler, interview by the author, Spanish Fork, Utah, March 31, 2006.

[18] Eichler, autobiography, 91.

[19] Ibid., 100.

[20] Ibid., 115.