Cottbus Branch, Spreewald District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 419-24.

The branch in Cottbus, Brandenburg, played a very significant role in the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints toward the end of World War II and in the following months. Located ninety miles southeast of Berlin, Cottbus had about 55,000 inhabitants when the war began. Industrially insignificant, the city was largely spared the ravages of war until January 1945. By the end of the war, it had become the gathering place for Saints from many branches in eastern Germany.[1]

| Cottbus Branch[2] | 1939 |

| Elders | 7 |

| Priests | 4 |

| Teachers | 3 |

| Deacons | 6 |

| Other Adult Males | 9 |

| Adult Females | 42 |

| Male Children | 11 |

| Female Children | 5 |

| Total | 87 |

The history of the East German Mission shows that Wilhelm Eckert was appointed president of the Cottbus Branch on May 1, 1938. His counselors were Adolf Duschl and Guido Schröder.[3] Eyewitnesses later identified the branch president as Fritz Lehnig, but this may have been a temporary and additional responsibility toward the end of the war because Brother Lehnig was officially the president of the Spreewald District throughout the war. The branch met in rented rooms at Lausitzerstrasse 53, a two-story structure owned by the Lehnig family. The upper story had been used as a restaurant but was converted into a chapel and a few classrooms. The cloakroom and the restrooms were located in an anteroom.

Joachim Lehnig (born 1935) recalled the following about the location of the building:

The restaurant in the building used to be called Zum Grauen Affen (“At the Sign of the Grey Ape”), but it was then used as a place where potentially recyclable materials such as paper or bones were collected. This property was very close to the train station, only a five-minute walk away, five minutes into the city and with the streetcar station close by.[4]

The branch observed the typical meeting schedule, with Sunday School held at 10:00 a.m. and sacrament meeting in the evening. Priesthood and Relief Society meetings were held on Monday evening with MIA meeting on Wednesday evenings. Jutta Obst (born 1939) later recalled that her parents always attended the meetings on Monday and Wednesday evenings, leaving their children at home under the care of their eldest son, Lothar.[5]

Although full-time missionaries were a rarity in Germany during the war, individual members continued to tell others about their church and their faith. So it happened that Heinrich Grünewald of Cottbus, a railroad employee, was introduced to the Church by an unidentified member riding the train one day. Heinrich was interested in the message and began to attend Church meetings in Cottbus. His wife, Anne Marie, was busy with their four little children but eventually attended with him. They were baptized together on July 18, 1943, in the Spree River. Heinrich and Anne Marie Grünewald had a very happy home. They taught their children the truths of the gospel and loved the gospel dearly. Like so many other Latter-day Saint fathers, Heinrich did not want to go away to war, but in 1944 the call came. With a premonition about not returning, Brother Grünewald asked the branch president to watch over his family, and he requested of his wife that she marry again if he died, for the children’s sake. Shortly before the end of the war, Heinrich Grünewald disappeared in the Soviet Union.[6]

The family of Otto and Marie Hagen lived at Neustädterstrasse 3 during the war. Brother Hagen was gone for most of the war as a test pilot for new airplanes. Sister Hagen took care of their three little boys. Their home was spared destruction during the air raids and the artillery bombardments. Sometime after the Allied invasion of France on June 6, 1944, Otto Hagen was taken prisoner by the Americans. Church events continued to be observed as well as possible during the war, as Joachim Lehnig attested:

I was baptized in January 1944 in the Spree River. Brother Schröder baptized me—a faithful member with five sons. The place where we usually baptized people was where the river was a little faster than normal so there was also no ice. The baptism took place in the evening hours when it was already dark. My father did not like to give in and accept restrictions for the Church.[7]

Max Obst (born 1903) was a supervisor at the Cottbus railway station. As such, he was classified as exempt from military service. This allowed him to spend the entire war era at home with his wife, Elfriede (born 1907), and their family; however, work days of twelve or more hours were not uncommon for him. In 1944, the Obst family moved to Moltkestrasse, just ten walking minutes from the main rail station.

During the last year of the war, Cottbus became a target of the approaching Red Army. Air-raid sirens wailed on a regular basis, but attacks were fortunately not common occurrences. At times, Brother and Sister Obst were in church when the sirens went off, and young Lothar (now twelve) would carry his three younger sisters, one by one, down into the basement shelter.

The invading Red Army arrived in the vicinity of Cottbus in early 1945. Jutta Obst later recalled one terrifying afternoon in February when Allied airplanes brutally pounded the city. She huddled with her mother and her siblings in the basement for two hours in “earth-shattering terror.” When the attack was over, the house still stood but was substantially damaged:

The power of the explosions broke loose all the doors, including their frames. The wall plaster had fallen off, and all the wall hangings and pictures were broken up; all over the floors. It was a bad scene, a terrible and depressing scene. But we were grateful that we were alive and physically unharmed. Poorly and scanty, we repaired everything and covered the windows with paper.[8]

Volker Hagen (born 1940) recalled what may have been the same air raid. The house next to his was destroyed by the bombs. He later told how the rescue squad “had to come into our fallout shelter and knock a hole in the wall to get to the people in the other bomb shelter next door. [That way they] got them into our bomb shelter to save them because their house was destroyed.”[9] The system used throughout Germany had worked again successfully.

Elfriede Grünewald on her first day in school in September 1944. The traditional Schultüte was filled with goodies. (E. Gruenewald Schulz)

Elfriede Grünewald on her first day in school in September 1944. The traditional Schultüte was filled with goodies. (E. Gruenewald Schulz)

As the war intensified in Cottbus, it was not even safe to walk the streets. Fighter planes swooped down and shot at civilians. On one occasion, Elfriede Grünewald (born 1938) and her brother, Gerhard, were playing outside. Gerhard was tied to a little wagon like a horse by a long rope. Suddenly, an airplane attacked, and Elfriede fled to the house while her brother crawled under the wagon. “We were terrified, but Heavenly Father protected us,” she explained. After that, when Elfriede’s mother sent her to the bakery, the little girl went from one house entrance to the next to make her way down the street safely.[10]

During one harrowing afternoon when as many as eight thousand people were killed in air raids on Cottbus, Anne Marie Grünewald had wanted to work in her garden but could not find the gate key anywhere.[11] When three successive alarms sounded, she prayed with her children and took them to the basement shelter. One bomb landed so close to the house that significant damage was done. When they returned to the kitchen, Sister Grünewald found the garden key on the kitchen table. She realized that if she had found the key earlier, she would likely have been in the garden when the bomb that damaged the home hit the ground. There were six bomb craters between their apartment and their garden plot.[12]

Early in 1945, the city government confiscated part of the Lehnig building. According to young Joachim:

[They took] the large meeting rooms because they used them as a station for the refugees from Silesia and East Prussia. They put wooden beds covered with straw and equipped with blankets in the rooms. They also installed bathrooms and a small kitchen.

Young Gisela Vogt (born 1939) had vivid memories of the dangers experienced in the last months of the war. As she recalled, “We went to bed with our clothes on [to be ready for an alarm]. Once, we were trapped in the basement, and it took about an hour to dig our way out. I once saw a little black body underneath a burned-out automobile. It apparently was the driver who had tried to hide there. You don’t forget those sights and smells.”[13]

By March, the Soviets were approaching the city of Cottbus, and the government encouraged women and children to leave, while the men were required to stay and defend the city. Along with about eighty other members of the Cottbus Branch, Max and Elfriede Obst took their four children and headed west. They were privileged to ride in a delivery van owned by a Brother Sasse. They stayed for several days in a barn near the town of Stradow, about ten miles west of Cottbus. In the meantime, the Red Army conquered Cottbus and just days later streamed past Stradow on their way to Berlin. The LDS refugees decided to return to Cottbus. As they did so, they were surrounded by confusion and destruction, as Jutta Obst recalled:

Everything around us was burning and on fire. Along the way we passed corpses of dead soldiers and dead horses everywhere. The stench of death filled the air. This gruesome sight of death, heaps of twisted steel and concrete, naked blasted walls, was so enormously frightening. . . . I remember being so anxious, nervous, scared, and trembling. The other side of the highway was crowded with Russians and their tanks with trucks, cannon, armored cars, soldiers, etc.[14]

Several eyewitnesses recalled that one of the wagons used on the return trek to Cottbus was pulled by two strong horses. Soviet soldiers confiscated those horses and replaced them with two very old and decrepit animals. On the way, Elfriede Grünewald was instructed to hold tightly to a beautiful young woman named Gerda Eckert (who was only twenty-one) and to call her “Mama” in case the invaders tried to molest Gerda.[15]

Marie Hagen also took her three sons and fled before the Soviets. When they returned from Stradow, their apartment was still intact but inhabited by another LDS family. After a short stay at the Lehnig home, the Hagens moved back into their apartment. According to young Volker, the Soviets soon went through the apartment looking for items to confiscate—principally radios and bicycles. The conquerors soon ordered that those and other specific items be surrendered by the citizenry at city hall.

Back in Cottbus, the Obst family joined the LDS refugee colony at the Lehnig property. In an attempt to protect the women from enemy soldiers (some of whom lived in a building next door), American flags were displayed on the property and were worn by the members of the group. However, as much as Fritz Lehnig and the other priesthood leaders of the group tried to protect the women from molestation, it simply was not possible on an everyday basis. Jutta Obst recalled that “in spite of Lothar’s tender age of thirteen–fourteen, he was made to witness one of the many rapes that even happened in Lehnig’s home.”[16]

Church meetings were held regularly at the Lehnig property, but the members had to gather in secret. The Soviet military occupation authority did not allow such meetings. On at least one occasion, enemy soldiers barged into the chapel during the sacrament service and menaced the congregation. Fortunately, they left without further incident.

The family of Fritz Lehnig suffered from the loss of three sons killed in the war: Werner, Alfred, and Reinhardt. In the recollections of young Joachim:

After 1945, we received notice from the Red Cross that Alfred and Reinhardt could not be found. I was the only one who saw my father sitting at his desk crying with his face in his hands. He stopped after a while and went back to work. He explained to us later that the gospel needs to be taught to every person and that Reinhardt and Fredi would now also be teachers [in heaven]. Reinhardt had served in the East German Mission in 1938 and 1939 and was drafted right after he came home.

Similar sentiments were not the reaction of the Lehnig family when they heard of the death of Adolf Hitler: “We burned his picture,” explained Joachim. Volker Hagen recalled visiting his father in a POW camp in the American Occupation Zone in 1946. Otto Hagen was freed in 1947 and joined his wife and sons in Cottbus. Marie Hagen had been working in a savings and loan company while he had been gone for nearly five years. He was in relatively good health but was tall and—according to Volker—“very skinny; he was just like a straight line.” Shortly after his return, Otto Hagen baptized his son, Volker, in the Spree River.

Sister Grünewald waited for years for Heinrich to return and did not remarry. When she died in 1987, there was still no information regarding his fate. In 1998, her children learned that he had died in a Soviet POW camp two days before Christmas in 1944.[17]

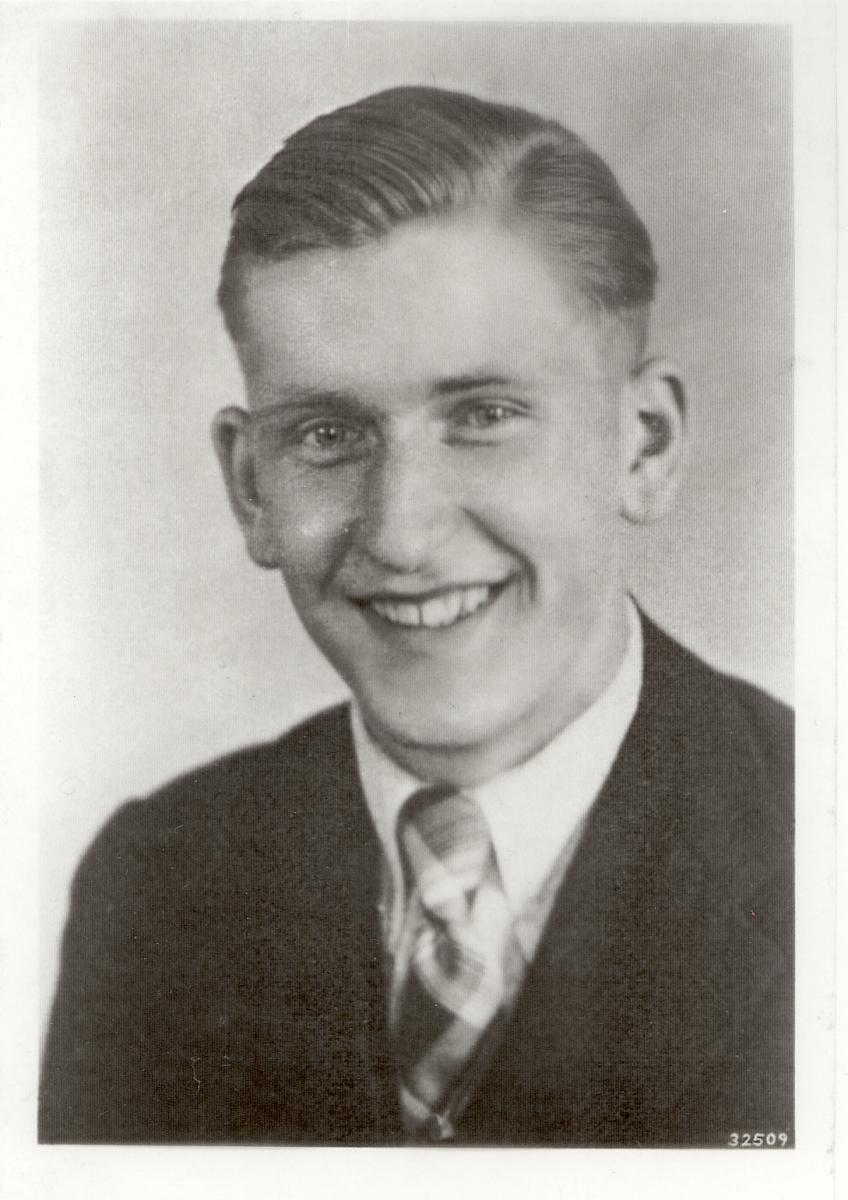

Heinrich Grünewald shortly after he joined the Church in 1943 (E. Gruenewald Schulz)

Heinrich Grünewald shortly after he joined the Church in 1943 (E. Gruenewald Schulz)

The Obst family left Cottbus in April 1946 and took up residence in another Latter-day Saint refugee colony—Langen, south of Frankfurt am Main in the West German Mission. Many other Cottbus refugee camp veterans joined them there. By the time most refugees had fled, the Cottbus Branch was smaller than it had been in 1939.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Cottbus Branch did not survive World War II:

Ernst August Wilhelm Heinz Grabke b. Cottbus, Brandenburg, Preussen 27 Aug 1919; son of Ernst Fritz Wilhelm Grabke and Anna Hedwig Martha Feiertag; bp. 27 Oct 1927; ord. deacon; k. in battle eastern Germany 1943 or 1945 (E. Gäbler; FHL Microfilm 25776, 1930 Census)

Ernst Fritz Wilhelm Grabke b. Cottbus, Brandenburg, Preussen 6 Jan 1881; son of Wilhelm Grabke and Marie Noack; bp. 3 Dec 1925; m. Berlin, Brandenburg, Preussen 8 Oct 1908, Anna Hedwig Martha Feiertag; 3 children; m. Cottbus, Brandenburg, Preussen 30 Mar 1930, Pauline Helene Marks or Voigt; d. Cottbus 6 Feb 1944 (IGI)

Heinrich Grünewald b. Neu-Beideck, Samara, Russia 3 May 1911; son of Balthasar Grünewald and Katharina Elisabeth Hill; bp. 18 Jun 1943; m. Cottbus, Brandenburg, Preussen 5 Mar 1938, Anna Maria Melcher; 4 children; corporal; d. POW Woroschilograd, Russia 20 Dec 1944 (E. Grünewald Schulz; IGI; AF; PRF; www.volksbund.de)

Joachim Lehnig b. Cottbus, Brandenburg, Preussen 29 Dec 1921; son of Fritz Alfred Lehnig and Anna Hildegard Salzbrenner; lance corporal; k. in battle southeast of Witebsk, Belarus 31 Dec 1943 (www.volksbund.de; FHL Microfilm 271386, 1930/

Reinhold Fritz Lehnig b. Crimmitschau, Sachsen 20 Mar 1919; son of Fritz Alfred Lehnig and Anna Hildegard Salzbrenner; bp. 20 Mar 1927; missionary East German Mission, 1938–39; m. 22 May 1940, Elsa Elisabeth Erna Niepraschk; 2 children; d. Stalingrad, Russia 9 Jan 1943 (www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Reinhold Lehnig (J. Lehnig)

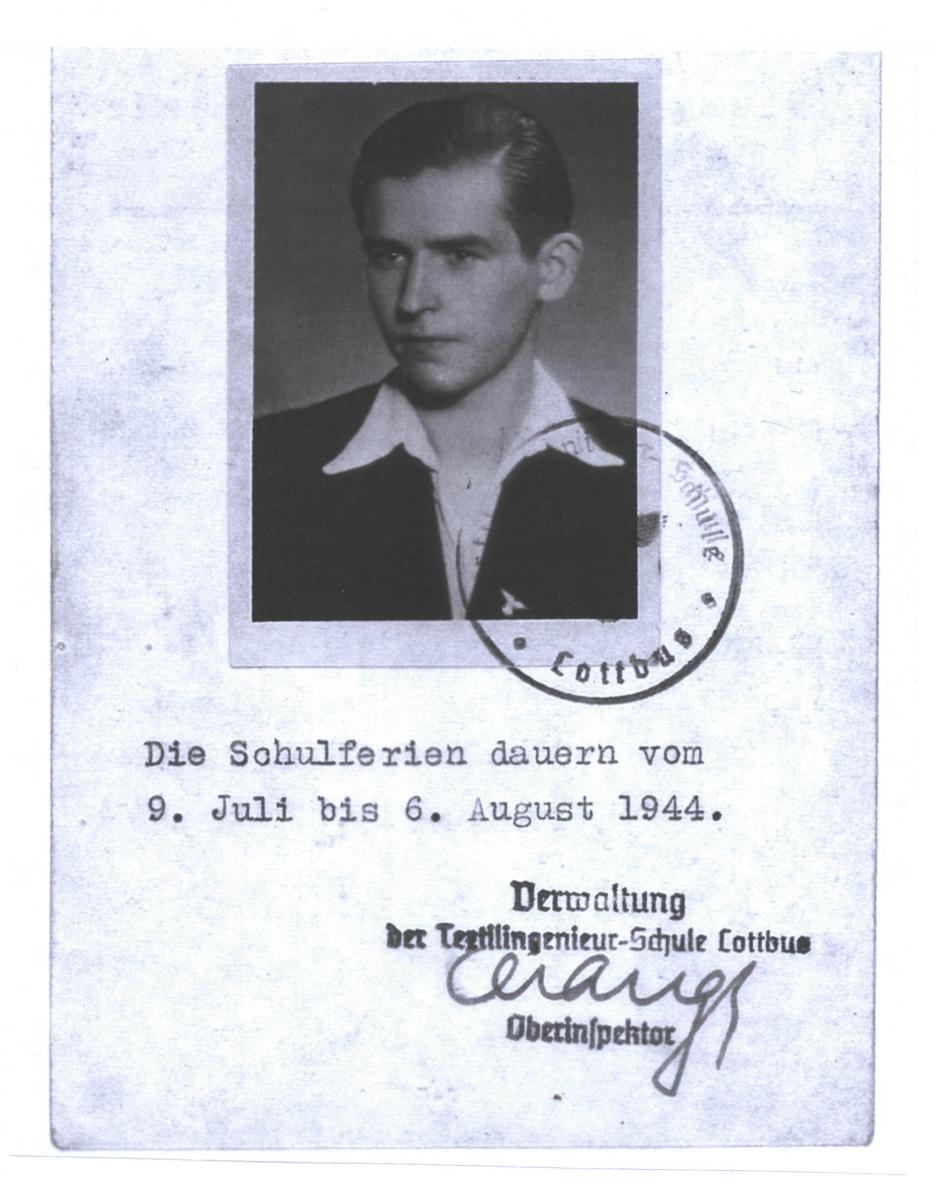

Wilhelm Alfred Lehnig b. Forst, Brandenburg, Preussen 26 Feb 1927; son of Fritz Alfred Lehnig and Anna Hildegard Salzbrenner; bp. 11 Mar 1935; d. 26 Mar 1945 (IGI)

Alfred Lehnig is shown here on his official school card. He died in March of 1945 (J. Lehnig)

Notes

[1] Elfriede Grünewald Schulz, autobiography (unpublished), 2; private collection.

[2] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[3] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, nos. 20–22, East German Mission History.

[4] Joachim Lehnig, interview by the author in German, Salt Lake City, June 16, 2007; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[5] Jutta Obst Burch, “Portrait of My Family” (unpublished family history, 2003), 4; private collection.

[6] Schulz, autobiography, 13–14.

[7] There is no official record of restrictions having been placed on the Church in Cottbus.

[8] Burch, “Portrait of My Family,” 7.

[9] Volker Hagen, interview by the author, Midvale, Utah, December 8, 2006. For details on this civil defense practice, see the introduction.

[10] Schulz, autobiography, 15.

[11] It was the custom in most of Europe to fence in the family garden plot (which was often not close to the home), and the gate was usually locked.

[12] Schulz, autobiography, 16.

[13] Gisela Vogt Berndt, interview by the author in German in Berlin, Germany, August 20, 2006; summarized in English by the author.

[14] Burch, “Portrait of My Family,” 8.

[15] Schulz, autobiography, 17–18.

[16] Burch, “Portrait of My Family,” 11. For additional details regarding life in the refugee colony, see the chapters on the Spreewald District and the Guben and Forst Branches.

[17] Schulz, autobiography, 14.