Chemnitz Center Branch, Chemnitz District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 165-84.

In 1939, the population of the Chemnitz Center Branch was 469, making it officially the largest branch of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in all of Germany. The city itself had about 375,000 inhabitants.

| Chemnitz Center Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 18 |

| Priests | 12 |

| Teachers | 12 |

| Deacons | 24 |

| Other Adult Males | 80 |

| Adult Females | 282 |

| Male Children | 16 |

| Female Children | 25 |

| Total | 469 |

The Center Branch rented two floors of a building at Schadestrasse 12, a few blocks south of the city’s center. The rooms were located in the first Hinterhaus, and there were quite a few, according to Ilse Franke (born 1915): “The chapel was a long room and we could divide it into classrooms. There was a class in the choir seats on the stand.”[2] Henry Burkhardt (born 1930) remembered a phrase painted above the podium: “The Glory of God Is Intelligence.”[3] A sign on the outside of the building indicated the presence of the Church there.

Herbert Heidler (born 1929) remembered seeing a very large number of children (eighteen years and under) in the Sunday School “because the first ten rows were filled with children.”[4]

Following the standard Sunday meeting format in Germany, Sunday School was held in the morning and sacrament meeting in the evening. At least one hundred forty persons attended meetings on a typical Sunday in 1939. Auxiliary meetings were held during the week—Relief Society and priesthood meetings on Monday at 7:00 p.m. and MIA on Wednesday, with choir practice on Thursday.[5] Ilse Franke fondly recalled her choir experience:

We always had a choir, and I was in every one—children’s choir, youth choir. I have sung all my life. My mother was the director. She always said, “You don’t have a solo voice, but you are a wonderful head.” She used the word head with the choir members. We had fifty voices one time, and sometimes we had a little orchestra—five pieces.

Young people of the Chemnitz Center Branch in 1938 (R. Schumann Hinton)

Young people of the Chemnitz Center Branch in 1938 (R. Schumann Hinton)

Because all of the Church programs were functioning in the branch, leadership meetings were also held. As Henry Burkhardt recalled, there was an advanced training class for the clerks before Sunday School on fast Sunday and a teacher improvement class every other Sunday from 9:00 to 9:45 a.m.

Just before World War II began, Ilse Franke was engaged to Hans Böttcher of the Berlin Center Branch. She had met him at the 1936 Olympic Games in Berlin, and then she waited while he served as a full-time missionary in and near Chemnitz. However, he was drafted into the German army soon after returning home in 1939, and their wedding was postponed. They finally married on December 8, 1939. The official ceremony took place in the civil registry office at city hall in Chemnitz, and the next day a Church service was performed in the chapel of the Center Branch, conducted by district president Karl Göckeritz. The Church service was informal because it had no legal validity in Germany in those days. The nearest Latter-day Saint temple was in faraway Utah. Ilse recalled the event:

We had no honeymoon. He had leave for five days, but it took two days to get to Chemnitz from Poland and two days to get back. My mother and my father would not let us sleep together the first night. The dinner included beef tongue—a delicacy in Germany, but my husband didn’t like it.

Heinz Bonitz recalled hearing the news that Germany had attacked Poland on September 1, 1939:

I listened to the radio when we heard that the Germans had gone into Poland. That is what I remember vividly. Nobody supported the idea of a war. My father had already served in World War I and my mother also. They knew what to expect. [6]

When the war began, Alfred Schulz (born 1899) prayed that as a husband and father, he would be spared military service. He was trained as an office worker and was pleased to be assigned to work at city hall. On several occasions, he was to accompany military units to the front, but his orders were changed each time and he stayed home.[7]

Members of the Chemnitz Center and Schloss Branches shortly before the war.

Members of the Chemnitz Center and Schloss Branches shortly before the war.

Being a member of the Church caused problems in school for Brunhilde Falkner (born 1929) and her elder sister. The principal did not like Latter-day Saints, so Brunhilde’s parents found it better to transfer their daughters to another school rather than to subject them to the principal’s harassment. Unfortunately, a five-minute walk to school then became a twenty-minute walk.[8]

The Nazi Party’s attempts to raise a generation of loyal youth involved the young people of the Chemnitz Center Branch as well. Reactions among Latter-day Saint youth varied, as is clear from the stories of several eyewitnesses. Just after the war began, Siegfried Donner (born 1930) turned ten and was inducted into the Jungvolk organization. “I liked it because of the uniform. I was plain and it made me feel kind of powerful. I was into music, and I played a horn in the marching band. But my mother was against it, because I sometimes had duty on Sundays.” However, things turned sour because Siegfried had long hair, and he was sent to work on a pig farm as a punishment. His mother, who suffered from a nervous condition, protested his treatment with the demand, “Don’t I have any rights for my own boy?” When a Hitler Youth leader answered in the negative, she shouted, “You lousy jerk!” Only a statement from her physician explaining her nervous condition saved her from incarceration, as Siegfried explained.[9]

Thanks to his job of delivering about two hundred newspapers every day, Hyrum Cieslak (born 1930) was able to skip Jungvolk meetings. His father also saw to it that Hyrum never missed a Sunday church meeting due to Jungvolk activities. Fortunately, Hyrum did not suffer any consequences because of his absence.[10] Such passive resistance to Hitler’s program of recruiting young people for his political purposes was common among LDS parents who sought similar excuses for their children.

Herbert Heidler was a member of the Hitler Youth but had an understanding with his adult leader regarding Sundays. He told the man that if there were Hitler Youth meetings on Sundays, he would not be in attendance. Herbert recalled that there was no training in weapons, but some of the songs they sang had words suggesting violence.

Some boys recognized the subtle goals of the Hitler Youth. Henry Burkardt explained that he “could see the problems. As part of the Hitler Youth, I came to understand the meaning and purposes of the Third Reich more and more. I promised myself that I would never be a member of the Party.”

Irene Härtel turned ten years old in 1941 and was inducted into the Jungvolk. One of the aims of the program was to teach German girls modesty and simplicity. Irene recalled, for example, that “I was not allowed to have a bow in my hair or wear earrings. . . . Hitler wanted a German woman or girl to have long hair tied in a bun.”[11] The girls were also taught domestic skills on a regular basis and were required to render community service.

Johannes Lothar Flade (born 1926) turned fourteen in 1940 and was inducted into the Hitler Youth. He is one of many Latter-day Saint eyewitnesses who gave a positive description of the experience:

I enjoyed myself. I was happy. I had a good time. Hitler Youth was just wonderful. I think it was on Tuesdays and Thursdays. [We did] mostly sports, and I was just excited about sports. I was very good. I could run fast and I could throw far and jump far. . . . The only thing that I didn’t do was meet on Sundays. They tried to threaten me, but I was so good in sports, they left me alone. I was already a leader at fifteen.

On New Year’s Day 1940, Hans Böttcher showed up in Chemnitz for a surprise visit. He had been released from the army on special request by his employer, who managed a critical war industry in Berlin. He was in civilian clothing and would not say what he was really working on, but said instead that he made “refrigerator parts.” He remained in Berlin the next two years, but his wife, Ilse, did not move there to join him. “I didn’t want to give up my nice apartment in Chemnitz and move my beautiful new furniture to that huge, scary city,” she explained. Hans was still in Berlin when their first son, Hans, was born in Chemnitz on April 15, 1941.

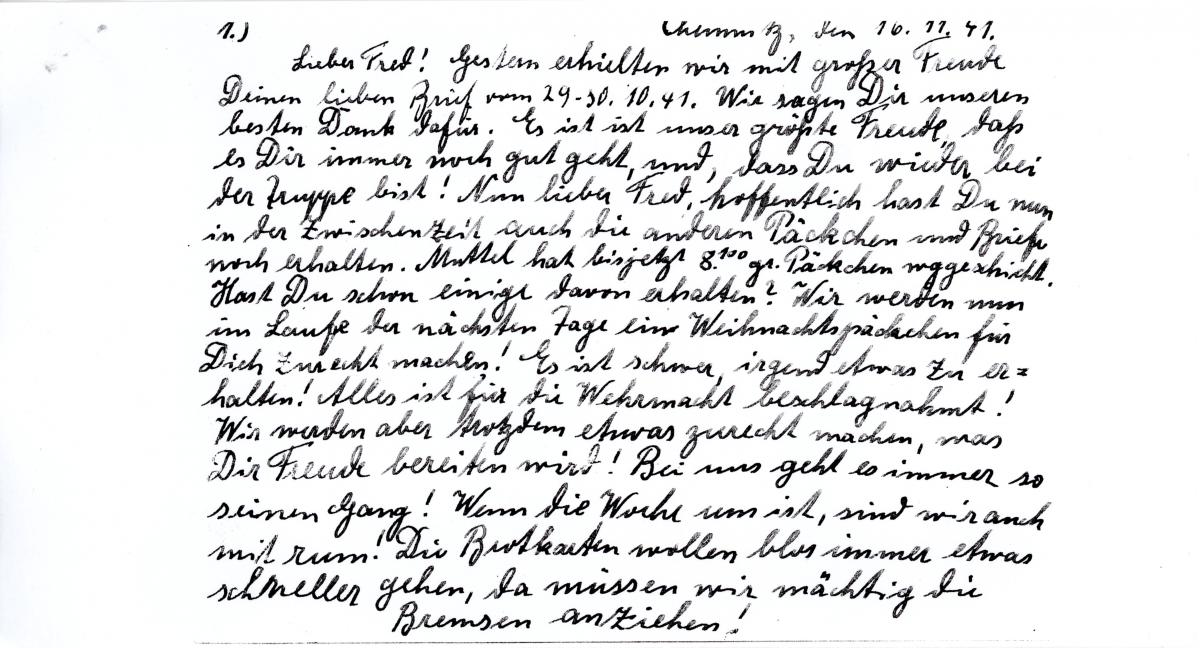

On November 16, 1941, Henry Burkhardt’s father, Richard, wrote one of many letters to his son Alfred (“Fred,” born 1922) on the Eastern Front. The letter was returned by Fred’s company commander when the young soldier was reported missing in action. The contents of the letter are typical among Latter-day Saint families in Germany during World War II:

Dear Fred,

Yesterday we received your fine letter of October 29–30, 1941. Thank you so much! We were so happy to receive it. It is our greatest joy that you are well and back with your comrades again! My dear Fred, we hope that you have been receiving all of the packages and letters we have sent. Mother has sent eight packages of 100 grams each. Have you received any of those? In the next few days, we’ll put together a Christmas package for you. It is so tough to get stuff. Everything is confiscated for the army. . . . It seems that our bread ration coupons are consumed earlier each week. . . . It’s terribly cold and stormy here right now. . . . In Sunday School they announced your greetings to everybody. And they all send their best wishes back to you. . . . I already told you that Erwin was wounded. I have been classified as fit for military duty again. So, everything’s fine, right? Mother is so pleased that you have recovered. She was really worried about you. The boys are very busy, as always. And little Christa can now recite four-line poems. . . . Well, I have to close now. Best wishes from Mother, Papa, and your siblings.[12]

For most of the war years, there were only slight changes in the Chemnitz Center Branch. Brunhilde Falkner could not recall interruptions in the branch meeting schedule or any interference or persecution on the part of the government. “I can remember though that the word Zion was not allowed to be used in our songs or talks.” This is consistent with observations made by eyewitnesses in other branches.

The members of the branch did their best to keep the rooms of the branch in the Schadestrasse in good order during the war. Sigrid Cieslak (born 1935) had the following recollection:

Usually at the time of harvest, the members would bring vegetables from their garden, the biggest ones, and they were displayed. And I remember especially my mother, she always would have a flower arrangement from our garden every Sunday during the season.[13]

The first page of the letter written by Richard Burkhardt to his son, Fred, in Russia in 1941 (H. Burkhardt)

The first page of the letter written by Richard Burkhardt to his son, Fred, in Russia in 1941 (H. Burkhardt)

One of the common memories of members of the Chemnitz Center Branch was a baptismal ceremony held in the backyard of the Emil Heidler home at Helbersdorferstrasse 7. Herbert Heidler provided some detail:

The basin in which we held baptisms was in our garden. It was just 10 meters [33 feet] away from our house and about 2 × 3 meters [7 × 10 feet] in size and about 1 meter [3 feet] deep. I was also baptized in this basin. Later in 1947, my father built an even bigger pool with the size of 7 × 3.5 meters [22 × 11 feet]. We baptized all year round.

Henry Burkhardt explained. “There were listeners in the branch, but our work was to proclaim the gospel.” The term “listeners” refers to government officials. He recalled that branch president Paul Auerswald was once asked to hang the swastika flag in church, but he declined; he wanted to keep the Church and politics separate.

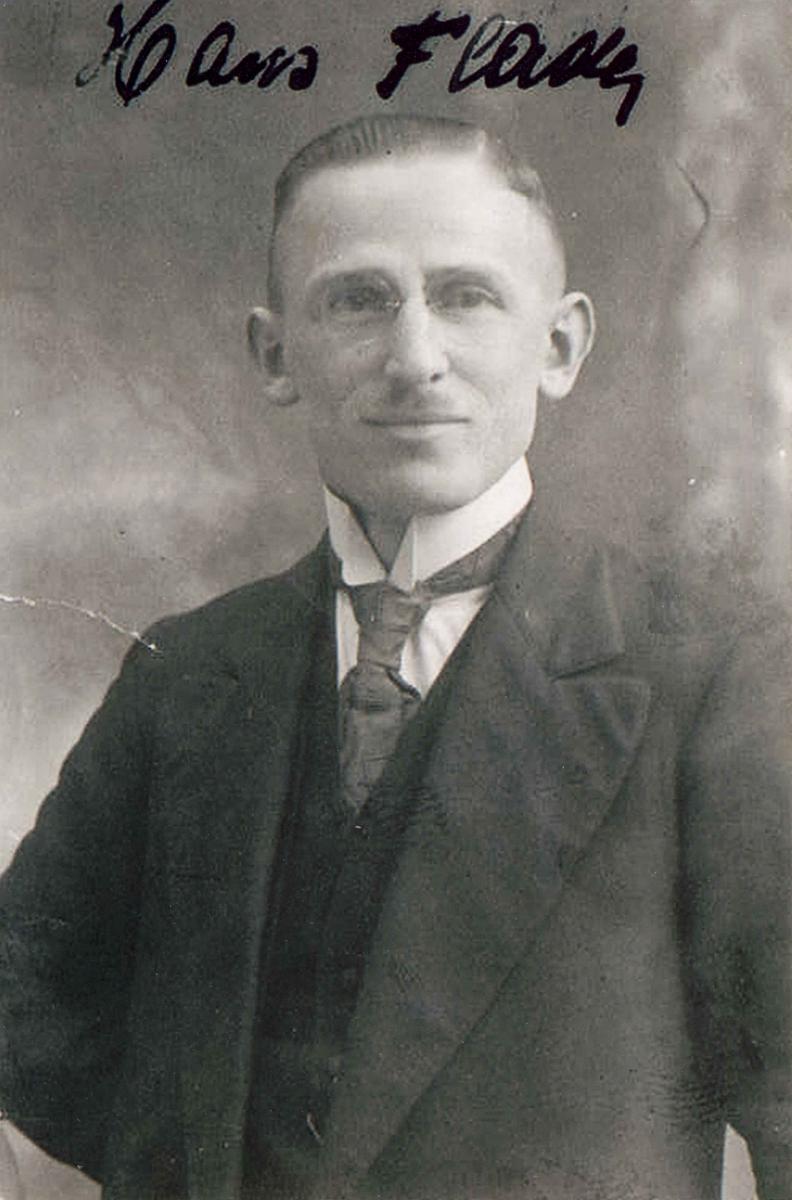

Some Latter-day Saints found it impossible to embrace Hitler and Nazism. Lothar Flade had the following to say about his father, Hans Emil Flade:

My dad was not an anti-Nazi because you couldn’t afford to be that way. You would end up in a concentration camp. But he was a scriptorian, and when you understand the gospel you know what’s coming. About Hitler, he said, “This is the beginning of the end.”

Lothar’s mother and his elder sister were initially swayed by the mass events sponsored by the Nazi Party, but they did not join the Party. Eventually they learned that Hans Emil Flade was right about Hitler and the direction in which Germany as a nation was headed.

Chemnitz Center and Schloss Branch members on an outing in 1940 (S. Donner)

Chemnitz Center and Schloss Branch members on an outing in 1940 (S. Donner)

At city hall, a female colleague once accused Alfred Schulz of making public speeches (in church) against the Nazi Party. He did not mention what the informer believed he had said but wrote the following about his treatment:

I was called in by the Gestapo and interrogated. I was able to prove that the allegations were false but was told that I must not associate myself with the Church any longer. I was to give up all callings in the branch. I spoke with the district president, and he advised me that this was in my best interest. Therefore, at the fall conference, I was honorably released from all of my callings.

In Nazi Germany, public statements criticizing the government could bring dire consequences. Such was the case with the family of Center Branch member Helmut Süss on September 2, 1942. Helmut’s wife, Elsa Elisabeth Jung Süss, was arrested and accused of making treasonous comments. In response, officials of the government took the couple’s three little children (Hanna and twins Edith and Eva) into custody and delivered them to an orphanage in Chemnitz-Bernsdorf. Years later, the matter was carefully studied by Sister Süss’s brother-in-law, Wolfgang Süss (born 1927), who summarized the information he collected as follows:

A resident of the same apartment building had denounced my sister-in-law to the police for making so-called treasonous statements. On one occasion, she was reportedly in a milk store and had complained about the lack of milk for infants. My mother was standing right next to her daughter-in-law and personally heard that comment, whereupon she instructed her to be silent. We do not know whether the informant cited other so-called treasonous statements made by my sister-in-law. However, it may be assumed that she would not have been arrested for a single such comment. Elisabeth was then arrested, put in jail, and we were not informed of her whereabouts. Her husband, my brother Helmut, was a soldier in France at the time. Elisabeth had two children from a previous marriage: her son Werner was placed with a farm family and her daughter Inge was taken in by the Diakonissen Order. . . . Both parents were allowed (under guard) to visit their children in November 1943, after which there was no more contact between the parents and the children or other family members.[14]

Hanna Süss, Elisabeth’s youngest daughter, later recalled the day her mother was arrested: “My mother was taken away when we were home on my birthday in 1942. We were waiting for my siblings to come back from school so we could eat together. We did not have a chance to say good-bye to each other.”[15]

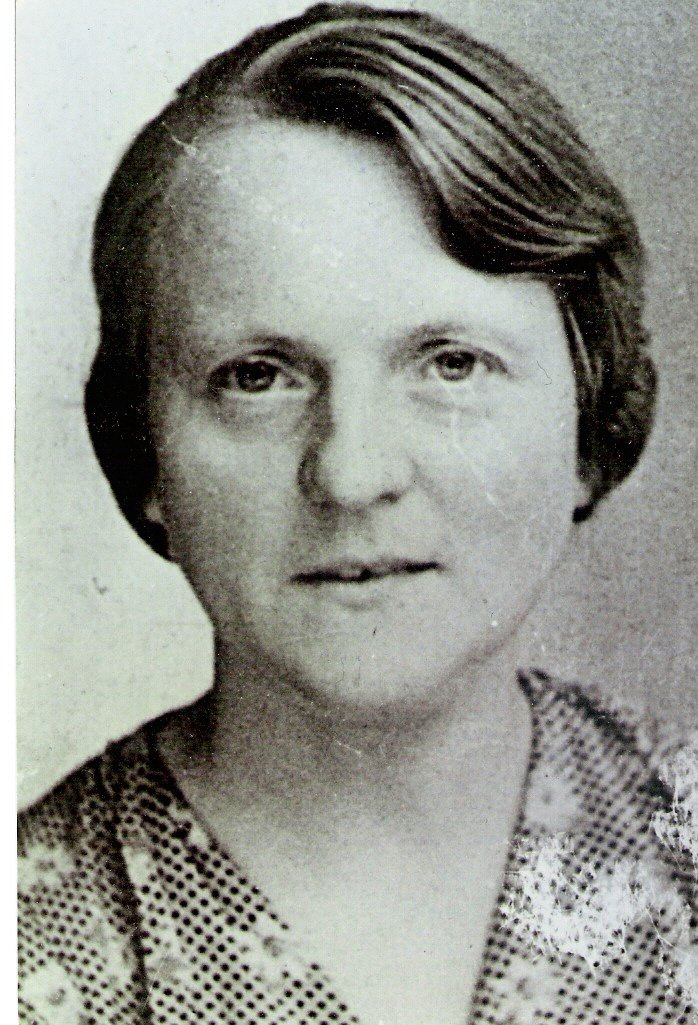

Elisabeth Elsa Jung Süss died in the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. (W. Süss)

Elisabeth Elsa Jung Süss died in the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp. (W. Süss)

According to Wolfgang Süss, his brother Helmut Süss was killed in France on September 5, 1944. Helmut’s wife, Elsa Elisabeth, ended up in the Ravensbrück Concentration Camp near Fürstenberg (eighty miles north of Berlin), where she died on January 25, 1945. Wolfgang’s mother was eventually informed of this in writing.

Regarding the charges against Sister Süss, her daughter Hanna later stated, “We never got anything in writing that explained why all of this happened.”

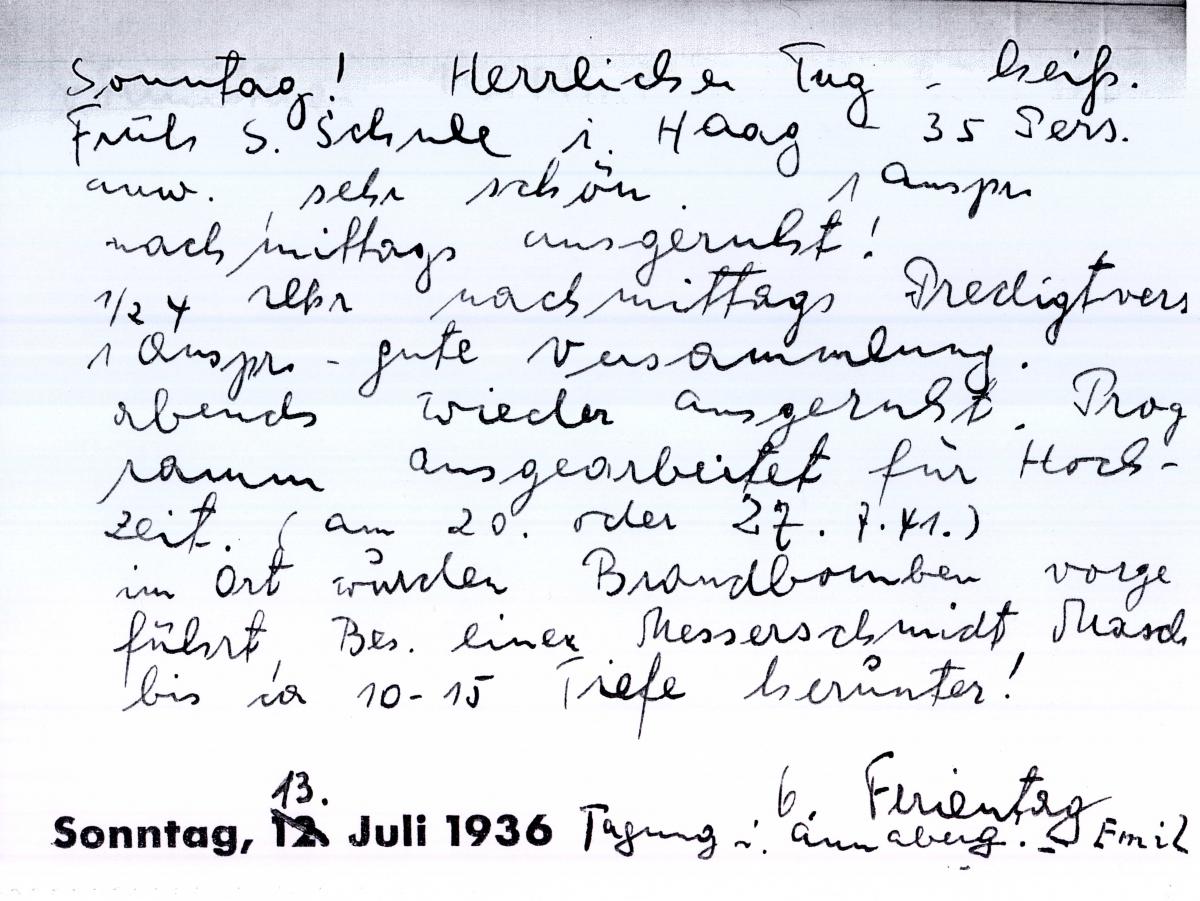

Life at home in a large German city was not all privation and suffering in 1941. District president Karl Göckeritz, an office manager, found time to go to Haag am Hausruck in Austria for a summer vacation. He left home on July 6, 1941, and was apparently gone for two weeks. While in Haag, he spent quite a lot of time with the Rosner family and other members of the branch there. His diary entries give the impression that he left his family at home in Chemnitz.[16]

District president Karl Göckeritz of the Center Branch enjoyed a nice vacation in July 1941. His diary entry indicates that he attended church in the Haag Branch in Austria. The diary was designed for 1936, so he had to change the dates. (H. Göckeritz)

District president Karl Göckeritz of the Center Branch enjoyed a nice vacation in July 1941. His diary entry indicates that he attended church in the Haag Branch in Austria. The diary was designed for 1936, so he had to change the dates. (H. Göckeritz)

That same year, Irene Härtel’s father was drafted into the Wehrmacht. She recalled the day he left their home in Jahnsdorf by Chemnitz:

My mother wept at home and we took the sled and went down with my father to where he had to meet the others. We wept and then our father was gone. When he came back for a few days of vacation once and wore his uniform, I cried that he would not be my father because he wore that [uniform]. I had never seen him in uniform before, and I will never forget that experience.

When the Wehrmacht unleashed its forces against the Soviet Union in June 1941, Alfred Schulz was immediately concerned, as he later wrote: “[Hearing about this] gave me a feeling of sadness. I had a kind of premonition, a worry that cannot really be described. . . . I could not believe that this would result in victory.”

Ilse Franke Böttcher’s husband was drafted again in 1942. His employment was no longer reason for an exemption when Germany was fighting on fronts all over Europe and in Africa. Back at home, Ilse gave birth to a daughter, Margaret, in October 1942. For several months, she lived with her children in the town of Bischofswerda, about sixty miles to the northeast of Chemnitz. Then she went to a small town in Austria with her children and her mother. However, that did not last long because Hans came to Chemnitz on leave and Ilse hurried home to see him. Life for Ilse and her children continued to be a merry-go-round as she followed Hans to a gunnery range in southeast Germany for several months, then returned to Chemnitz when he was sent to Italy.

Daily life during wartime can be challenging and serious, but the normal emotions of young people do not disappear. For example, Lothar Flade was a youth of sixteen when he and two friends were preparing for a 1942 district conference by hanging a large sign over the stage in the Schadestrasse meeting rooms. He later wrote about the incident that occurred at that moment:

I heard the door open at the other end of the chapel. I turned around and saw three young girls enter. One of those girls [Alice Wagner of Annaberg] wore a blue dress and a blue hat. I will never forget it. Something happened to me as I was looking at this girl. I knew at that moment that I was looking at my future wife.[17]

Charlotte Popitz (born 1915) recalled her wartime wedding fondly:

I got married in 1942. In the morning, we went to the civil registration office [at city hall] and in the afternoon we rode in a wedding carriage because gas for a car was not available anymore. It was beautiful. The Chemnitz [Center] Branch was in the Schadestrasse. We met in a factory building, and the priesthood holders had decorated everything beautifully for our wedding. Brother Karl Göckeritz married us in the afternoon. The whole branch celebrated together. . . . The choir sang, and one brother sang a beautiful song.[18]

Sister Popitz Ficker had little time to celebrate with her husband. He had been granted two weeks furlough and was then on his way back to Budapest, Hungary.

On August 28, 1939, Irene Härtel (born 1931) became a member of the Church:

I was the baptized in the backyard of the Heidler family because they had a little pool. We took my father’s motorbike, and there we were not allowed to have three people sitting on it, but we went that way to my baptism, and I was sitting on the tank and my mother behind my father. We also got a little bouquet from [the Heidler’s] garden, and I was confirmed in their living room. I remember it vividly. That day, other people were baptized also.[19]

During the war, Siegfried Donner and his mother were mostly on their own. His father was a government employee and worked at aircraft production facilities such as Peenemünde, where the V-1 rocket was built. “He was hardly ever at home,” Siegfried later explained, “My mother and I lived from whatever we could get. She even chopped up mice to feed to the chickens. If people had known, they wouldn’t have eaten the eggs. And she faithfully paid her tithing. Both of my parents did.”

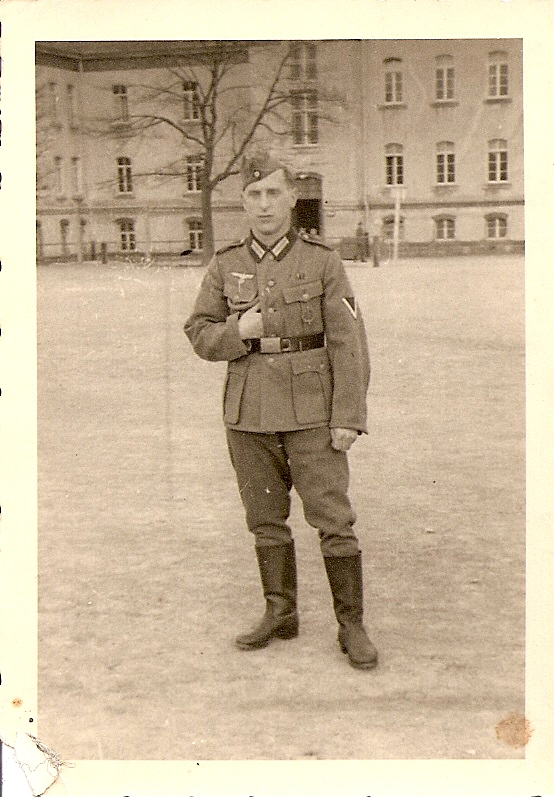

Lothar Flade volunteered for service in the German armed forces. As a leader in the Hitler Youth, he knew that a draft notice was heading his way within months and that he was bound for a specific unit that did not interest him. Volunteering would allow him to join a unit of his choice, in this case the Waffen-SS. This he did in 1943.[20] Because the Waffen-SS troops were under the command of one of Hitler’s closest comrades, Heinrich Himmler, the soldiers received much better care than common army soldiers. As Lothar later explained:

By the time we got into Russia, I saw those poor slobs [regular army] walking along in 45 or 50 degrees below with the storm howling across the fields. I was sitting in a car. We had better food, better weapons. We never had to walk; they drove us every place. It was just wonderful.

By early 1944, Lothar Flade, though still seventeen, was already the leader of a platoon of soldiers in the communications corps. It was their job to lay and maintain wires providing communications among frontline units. Such units suffered heavy casualties, but Lothar was not wounded: “I was just lucky and the Lord took care of me.” A few months later, he volunteered for duty elsewhere and was sent to Normandy in France.

In 1943, Leopoldine Cieslak followed the advice of city officials to protect her children from the ravages of war by sending them to live with relatives in small towns. Sigrid was sent to live with her grandmother in Riesa. She was to stay there until her father came home. Because her grandmother was not a member of the Church and there was no branch nearby, Sigrid was isolated from the Church until 1947, when her father finally returned from an American POW camp.

Hyrum Cieslak was sent to Rittmitz to live with a family on a dairy farm. There he continued his apprenticeship in dairy farming and joined the Wächtler family in attending church in the the Döbeln Branch, about four miles to the northwest. He did not return to Chemnitz until the summer of 1945.

The Wächtler family in Rittmitz (S. Cieslak Rudolph)

The Wächtler family in Rittmitz (S. Cieslak Rudolph)

The tension of air raids and impending death were still vivid in the mind of Susanne Flade Groebs (born 1915) when she described the situation years later:

We spent a lot of hours in the basement of my parents’ house. The sirens were always wailing and it was horrible. We heard crashing all around but nothing happened to us. . . . Nobody wanted to be alone during a raid, so they gathered together. You never knew if a bomb would fall on you. I never want to experience that again.[21]

As a young mother at home without her husband, Ilse Franke Böttcher was pleased with any kind of support she received. Her parents still lived in Chemnitz and helped where they could. Both of her children were born in a local hospital, and the state provided the usual incentives: she was awarded 20 marks (five dollars) each time she nursed a baby for the first six months.

Throughout the war, strict measures were needed to black out German cities at night. Siegfried Donner later explained how windows had to be totally covered so that not the slightest bit of light escaped. “They [the wardens] came and knocked on your windows [if they saw light]. If they came twice, you were in trouble. They thought you were trying to tell the British where we were.”

One evening in 1943, Alfred Schulz came home under the usual black-out conditions and saw a glimmer of light from a window in the living room. Aware of the possible penalties for nonobservance of blackout regulations, he attempted to fix the problem. While doing so, he fell and broke several ribs. He spent the next five weeks recuperating in his apartment.

One of the most difficult aspects of air-raid alarms for Ilse Franke Böttcher was the fact that she had to go from the fourth floor of her apartment building to the basement with her two little children. It seemed that nobody in the building was able to help her. “We had to go to the basement, or they [the insurance company] would not pay if you were killed. But if you were dead, you didn’t get the money anyway.” Each time she left the apartment, she carried her most valuable papers with her.

Chemnitz Center Primary children (S. Cieslak Rudolph)

Chemnitz Center Primary children (S. Cieslak Rudolph)

In the village of Jahnsdorf, the Härtel family lived in an apartment house without a basement, thus when the alarm sounded they walked (or ran) about a hundred yards to a restaurant called Der Felsenkeller. According to Irene, who was not scared that they would be killed:

We always tried to wear as much clothing as possible in case we had to stay away from home for a long time. Sometimes, we had to go into the shelter up to twice or more a night, especially during the last year of the war. We were there a total of fifty times or more. When there was an alarm, we got our luggage that was already prepared and ran to the shelter. The luggage was packed only with necessities.

Several times, Irene hid with her mother and her siblings in a cave behind Der Felsenkeller. The cave went no more than a hundred feet into the mountain and would not likely have protected them if a bomb had landed close to the entrance.

On June 6, 1944, the Allies launched the largest invasion force ever assembled. Crossing the English Channel, they set more than 100,000 soldiers on the beaches of northern France in an attempt to breach Hitler’s so-called Fortress Europe. A few days later, Lothar Flade arrived to join the defensive effort, having just come from the Soviet Union. One month later, the Germans had yielded ground back to brigadier general Henri-Jean Lafontaine, where the war came to an end for Lothar, who was still only seventeen:

When I woke up, I was lying in a hole. [The enemy] had overrun our position and machine-gunned us, and my friend was cut in half and lay there dead next to me. Then they threw one of those little grenades and knocked me out. When I came to, I couldn’t see, and I figured out that I had blood running down into my eyes. I had a couple of pieces of shrapnel in my skull. I scraped them off and must have had a concussion. There was nobody around, so I started to walk to where the Germans were. I came to the edge of the forest, and I found three rifles pointing at me. . . . [The enemy soldiers] just looked at me, and I said, “I’ve got to take a leak.” (I spoke English.) The Canadians began to laugh. I took care of my business, and then they led me away.

Irene Härtel Schönfeld stands at the entrance to the small cave that was used as an air-raid shelter in 1945. The gate was added after the war. (J. Larsen, 2007)

Irene Härtel Schönfeld stands at the entrance to the small cave that was used as an air-raid shelter in 1945. The gate was added after the war. (J. Larsen, 2007)

Charlotte Popitz Ficker had no children during the war, so she was employed and prayed for her husband to come home safely. His last furlough during the war was in 1944, after which he wrote to his wife a few more times. He told her that he was in Austria, then in southeast Germany, where he was a fireman and disarmed bombs. He was captured there by the Americans in the spring of 1945. Because he spoke English very well, he was given favored status among the German prisoners of war, meaning more food and more pleasant work assignments.

The air raids over Chemnitz left the Falkner family intact, but disease took a heavy toll. The year 1944 turned out to be very difficult for Brunhilde Falkner. “In January I moved to Zwickau because both my parents passed away in 1944 due to illness. My mother suffered from cancer and passed away in January while my father had a heart condition and passed away in December.” She moved in with her grandparents, who were not members of the Church. Brunhilde was pleased to belong to a good branch for the remainder of the war.

Throughout 1944, Alfred Schulz served the Reich in various administrative positions. For most of the year, he was in Potsdam by Berlin, but he also spent time in a very quiet and pleasant area of Russia. He was never in any danger. Late in the year, the call went out for all older men to report for duty in the Volkssturm (home guard). For the first few weeks, he was exempted due to his work at city hall, but he contributed by giving blood on many occasions. He also helped out in rescuing people from the ruins of bombed-out buildings.[22]

As a student at the State Academy of Technology, Heinz Bonitz was exempt from military service for a time. He had already spent three months in the Reichsarbeitsdienst, working not far from Schneidemühl. By 1943, the fatherland needed him more as a soldier than as a student, so he was drafted. Following his training in Kolberg and in Teplitz-Schönau, Czechoslovakia, he was a lieutenant of artillery.

Just after the year 1945 began, Heinz was shipped across the Baltic Sea to the Kurland (the German name for the occupied Baltic States). He was wounded there by shrapnel on January 27, 1945. While he was recovering in a hospital in Latvia for the next month, his unit was moved across the Baltic to defend the German heartland. When he received new orders, he doctored the papers to show that he was to report to Stettin, then proceeded to the harbor in nearby Riga. With SS troops on the lookout for soldiers trying to leave the combat zone without authorization, Heinz needed some trickery to board a ship. He later described how this was done:

I took off the insignia from my uniform to look like a common soldier and ran towards the ramp where they were loading [wounded] soldiers onto the ship. I grabbed somebody’s legs and helped them carry him aboard. This is how I got onto the ship. . . . Then I hid in hopes that they would not find me. [About six hours later] the ship left the harbor.

In early 1945, Ilse Franke Böttcher took her children to Aue, about twenty miles south of Chemnitz, to live with her aunt and her uncle. By doing so, she missed the worst hours in the history of her hometown.

On Monday, March 5, 1945, the city of Chemnitz was the target of several massive air raids, and much of the city was reduced to rubble overnight. The first attack occurred just after noon, and another came in the early evening. It was then that what may have been the single worst tragedy among Church members in Germany during World War II occurred. Bruno Fischer and his wife Johanna sought refuge in their basement. Their daughters Elisabeth and Erika happened to be there for a short visit, their soldier husbands being far from home. Erika Fischer Lohberger also had her two little boys with her. In addition, two elderly sisters from the Chemnitz Center Branch came from their apartments nearby to be with the Fischers. Survivors reported that the entire building was leveled by the direct hit of a large bomb. Apparently, everyone in the basement of that structure perished instantly—at least eight members of the Chemnitz Center Branch.

Elisabeth Fischer and Heinz Hänsel were married in 1943. (E. Göckeritz McClellan)

Elisabeth Fischer and Heinz Hänsel were married in 1943. (E. Göckeritz McClellan)

Bruno and Johanna Fischer perished in their basement along with six other members of the Chemnitz Center Branch. (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

Bruno and Johanna Fischer perished in their basement along with six other members of the Chemnitz Center Branch. (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

The death of the Fischer family was a trial for the Chemnitz Center Branch members. Charlotte Popitz Ficker recalled how she felt when she learned that they had been killed:

I had known [the Fischers] and was extremely hurt when they died, and this was one time I doubted Heavenly Father. And I asked myself why Heavenly Father would let this happen. My mother reminded me how nice it was that this family was together again.

Charlotte’s mother was referring to the fact that the husbands of the two Fischer sisters—Helmut Lohberger and Heinz Hänsel—were both killed in battle.

Herbert Heidler also had clear memories of that terrible night:

I looked out of my window on the fifth floor and saw how all the bombs were dropped on Chemnitz. They dropped phosphorus and people burned alive. They ran to the next pond trying to extinguish the fire but when they came out [of the water] they were burning again just seconds later. They stayed in the water until somebody helped them to scrape off their skin. These were the most horrible scenes I had to witness.

During the night of March 5–6, Henry Burkhardt felt for the first time that he might die: “My life was seriously threatened. . . . I came out of the basement with a wet blanket over my head. That was the only time I thought I would not survive.” As bad as things were, he recalled that the war taught him to be without fear.

Days after the attack on Chemnitz, Emil Heidler, acting president of the Chemnitz District, sent his son, Herbert, to inquire after the fate of the Fischers. On Sonnenstrasse in front of the ruins of the Fischer home, Herbert found the bodies covered up, already in a most hideous condition. He retrieved some personal items and conveyed them by bicycle to Bruno Fischer’s surviving daughter, Hildegard, in Niederwürschnitz, about nine miles to the southeast.[23]

Siegfried Donner, who lived just a few streets away, also went to inquire about the Fischers and saw the bodies. They were badly burned and already covered with lime. Siegfried then went looking for his best friend; Ludwig Fedelmann was not a member of the Church but a neighbor and a close school friend. His family had sought refuge in the basement of the school rather than at home, but they perished when the school was also reduced to rubble. The next day, Siegfried helped dig his friend out of the rubble, bloodied and dead.

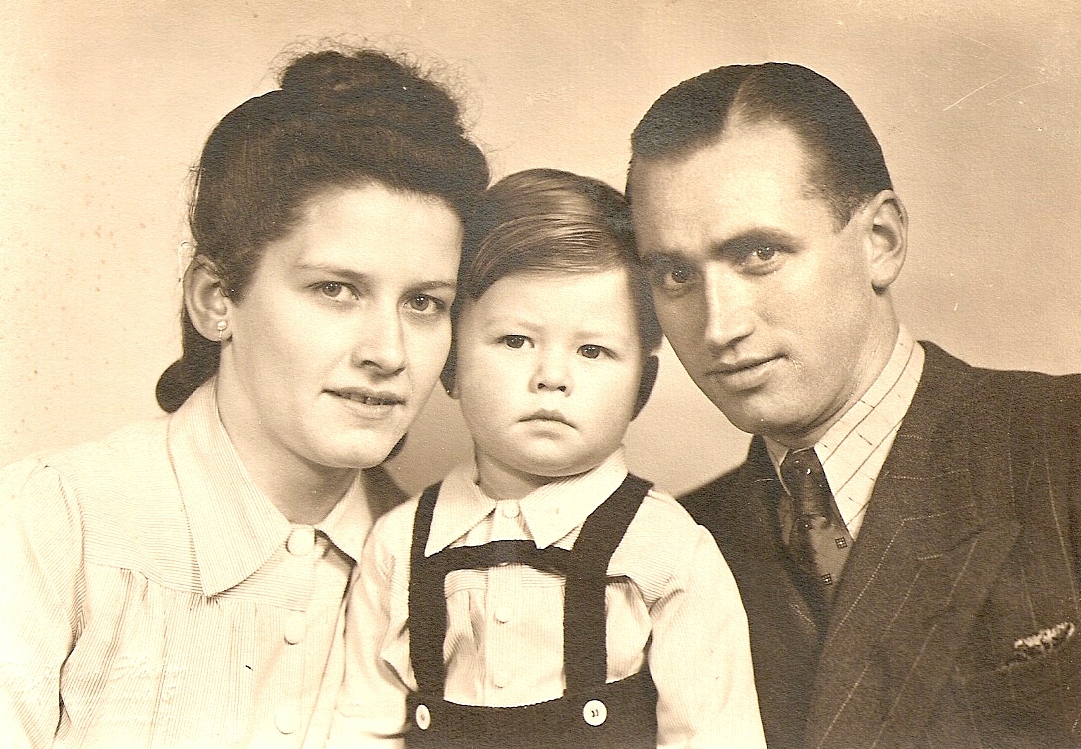

Erika and Helmut Lohberger with their son Peter in about 1942. All three and son Heinz (born 1944) died in the war. (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

Erika and Helmut Lohberger with their son Peter in about 1942. All three and son Heinz (born 1944) died in the war. (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

Reiner Gröbs lived with his family in a suburb about four miles from downtown Chemnitz. He was not yet five years old at the time but years later still had distinct memories of the attack:

I remember the shock of the antiaircraft: Boom! Boom! Boom! Boom! And I remember after the raid was over. . . . We climbed up to the upper story and opened the window. . . . Above the pine trees we could see the flames shooting up. [There were] four or five inches of new snow, and it was really kind of eerily beautiful, because the flames cast purple and orange and red and yellow shadows on the freshly fallen snow.[24]

Hanna Süss was living with her grandmother at the time. They had spent the night in a shoe factory across the street from the apartment. Later, they were taken to the fire station, where her grandmother discovered that one of the twins was missing in the confusion. Fortunately, the girl was found safe.

Young Karl Heinz Göckeritz (born 1935) recalled that in the aftermath of the air raid, an enemy airplane was found lying in the middle of the playground across the street from his home. Years later, he described the experience:

It was right in the middle of the playground; . . . it didn’t hit anything. In the morning when it got light, the police came, but before the police came, all the kids went over there. I was there too. The pilot was laying there dead. He just had one of those little hats on, like a little motorcycle helmet. Then the police came and covered everything up. He was lying outside the plane, but the plane wasn’t on fire or anything. He must have just crashed straight down. Everybody took a piece of the airplane.[25]

From a farm in Hainichen, Hyrum Cieslak could see that Chemnitz was in trouble. As he later explained, “We saw the sky full of planes all day long.” On a bike, he made the twelve-mile trip to Chemnitz to determine the status of his mother. Making his way through the rubble of the city, he saw “bodies stacked like cordwood.” He learned that “neighbors had wondered why my mother had been so calm and did not seem to panic about all the people dying around her. She told them that she prayed. She invited everybody to pray with her and they did.”

Among the many structures that disappeared under the bombs and the fires of that terrifying night were the rooms of the Chemnitz Center Branch at Schadestrasse 12. All of the Church property in the rooms was lost. Henry Burkhardt went there the day after the attack and described the situation in these words:

We went to the branch house on March 6. It was still burning, and we could see how the piano and the organ had fallen from the upper floor to the main floor. Everything was gone. We did not have a meetinghouse anymore. . . . Then we held our meetings in little groups on Sundays because the Schloss Branch rooms were too small. The home teachers informed us where we should meet.

The Schloss Branch meetinghouse at Winklerstrasse was undamaged in the attack. However, after the devastation of the city on March 5, many members were not able to get there, so they held meetings in apartments still intact. As Charlotte Popitz Ficker later recalled:

We also held meetings in people’s houses. Sometimes, there were fifty members in one room. People sat on the windowsills and on anything they could find. Even nonmembers attended who lived in the same house because they were interested in what we had to say. We did not have the sacrament in those meetings.

During most of the war years, the Härtel family of Jahnsdorf had taken a train and a streetcar on their way to church (a distance of six miles). These means were interrupted as a result of the March 5 air raid. As Irene remembered:

We had to walk [to church] after that. I remember one Sunday at the end of the war when we attended the [Schloss] Branch and we had to walk for three hours just to get there. The main hall was very small, and the younger people were asked to stand up and let the elderly sit down. We were young and stood up but had already walked all the way. My sister was very tired and sat down outside of the main room. Later, we found a shortcut to the Schloss Branch, and it did not take three hours anymore. On the way there, we sang songs or took a break to eat something. . . . [Between meetings] we stayed with other families [in town].

In late 1944, branch president Hans Emil Flade was asked by local Nazi Party leaders to assume the position of block air-raid warden. He declined the request. He indicated that his job as the manager of a factory and his work for the Church left him no time to be the warden. His son, Lothar, later learned from his mother that his father had been called “a swine and all kinds of other things,” but he had refused to yield. Two weeks later, Hans Emil Flade was picked up by the police and transported to Berlin to work on a rubble detail, helping to clean up the ruins of the Reich’s capital city. He was essentially a political prisoner.

Hans Emil Flade died in Berlin in the last week of the war. (J. Flade)

Hans Emil Flade died in Berlin in the last week of the war. (J. Flade)

In early March, Heinz Bonitz left the ship that had conveyed him from Riga, Latvia, to Swinemünde, north of Stettin. While the SS detained him (which again could have been disastrous), the air-raid sirens began to wail, and he went down into a shelter. During the attack, “the building swayed so much that it felt like we were on a ship.” Taking advantage of the confusion, he sneaked out and walked northwest toward Wolgast. There he was detained by police again but managed to escape and board a train south to Pasewalk, then east to Stettin. By some miracle, Heinz actually found his unit there.

Hitler’s birthday, April 20, was always an occasion for bombastic radio announcements. Heinz recalled hearing a speech by Joseph Goebbels, the German propaganda minister, in which he said something akin to this: “After this long and dreadful conflict, we will be able to place a laurel wreath on [Hitler’s] head.” The enemy was apparently not impressed by the message and began to shell Heinz’s position; he was hit in the arm by shrapnel. Still able to walk, he headed for Stettin with a comrade, then decided not to seek a hospital there but continued westward. During the next two weeks, he slowly made his way west across the province of Mecklenburg, then north through Schleswig-Holstein to the city of Flensburg—just short of the Danish border.

On April 23, 1945—just two weeks before the German surrender—Johannes Heidler was killed fighting the invading Red Army. His brother, Herbert, recalled the situation clearly:

We received notice of my brother’s death. There was a boy whom we recognized as a friend of my brother. He told us how he was a witness when Hans was shot. But he also told us that they had to leave him because the Russians had already started a new attack. Since then, my mother always wondered if he was really dead or still alive and maybe taken by the Russians. This thought never left her, and she prayed for clarity in this matter. One morning, we woke up early and my mother was very happy. She told us how she had seen her son during the night in her bedroom. He was dressed in white, and he smiled at her, and she knew that he was happy, although he did not say anything to her.

When the Soviets encircled Berlin in late April, Alfred Schulz was caught in the city. As a Volkssturm soldier, he knew that his chances for survival were poor. He changed into civilian clothing but was still rounded up by enemy soldiers. While Germans were being executed right and left, he too was shot in the neck. Fortunately, the bullet missed a fatal target by mere millimeters, but he fell as if dead. He later wrote about the wound he suffered:

A nerve was separated, and I was paralyzed over half of my body. Later, it was determined that the fifth vertebra in my neck was destroyed and the sixth about seventy percent damaged. I was curious about the process of dying. Everything went black. . . . When I came around, I was lying on my back among many others. I didn’t know if they were dead or alive.

During the weeks after the fall of Berlin, Alfred Schulz recovered enough to be able to walk a bit. By a miracle, he was able to get a message out of the facility where he was held prisoner, and that message was later delivered by a missionary to his family back in Chemnitz. Eventually, Alfred was classified as unfit for labor and released to return to Chemnitz. “It was a glorious reunion,” he explained. “The neighbors and the branch all welcomed me home with great joy.”

As a POW in Scotland, Lothar Flade became a beneficiary of his father’s good works. Before the war, Hans Emil Flade had warned a Jewish colleague of impending danger, so that the man was able to escape the Gestapo and immigrate to Switzerland. That same man later became an officer in the British army and recognized the Flade name. He located Lothar, told him the story, and stated, “If you are half the man your father is, I will help you.” That help came in the form of a transfer to a POW camp in Texas, rather than in Canada.

In the summer of 1945, Ilse and her two children left Aue and returned to Chemnitz. Trying to find a place on the train back home for the three of them proved to be a major challenge, given the confusion at railroad stations all over Germany at the time. At one station, a woman conductor was quite rude to them but was scolded by Ilse’s three-year-old son, Hans, who said, “You’re just an old witch!” His defiant accusation brought about a change in the woman’s attitude, and she found a way to get them into the train.

When World War II ended, Anni Franke exclaimed to her daughter, Ilse Franke Böttcher: “We’ve lost everything but you, and it doesn’t matter. We’re alive!” Ilse returned to Chemnitz with her children and found that most of the surviving Saints were meeting in the rooms of the Schloss Branch on Winklerstrasse.

Just after the war ended, Heinz Bonitz was able to attend church in the Altona Branch near Hamburg. During the summer of 1945, he secured official papers from the British occupational authority confirming his status as a free man. “I was never taken prisoner by anybody,” he later recalled. By November, he could return to the Soviet occupation zone and his hometown of Chemnitz. Unfortunately, his mother had died just a week before, and he found his home destroyed. Heinz explained that his survival was due to a promise made by President Heber J. Grant during his 1938 visit to Dresden: “He told us that whatever happened, we would not perish, but would come to Zion. I did not doubt that. I knew that the war could not stop that.”

The aftermath of the bombing in Chemnitz (S. Wagner Flade)

The aftermath of the bombing in Chemnitz (S. Wagner Flade)

Many years later, Susanne Flade Groebs explained what happened to her spiritually during the war years when she worked hard to raise her son, Reiner, while her soldier husband was gone: “My testimony became stronger and stronger. I prayed that our Heavenly Father would ‘deliver us from evil.’”

Regarding the entire war experience, Henry Burkhardt summarized his feelings in these words: “The gospel was the foundation on which we survived this time. I do not know how we could have survived without the gospel in our lives.”

Herbert Heidler made the following remarks when he contemplated the attitudes of the Chemnitz Center Branch members at the end of the war:

There was a family who had lost all they had, and the next morning they stood up in sacrament meeting and bore testimony and were grateful to be alive. Even the mothers who had lost their sons in the war stood up and were grateful for their lives. Somebody once said during a meeting, that we do not know the answer to everything and there will be tough situations, but we will one day know the answer to all of these questions.

Lothar Flade was in Texas—far from Europe—when the fighting ended. He was eventually moved from Texas to Arkansas, then to Alabama, then to Pine Bluff, Arkansas, where he worked in a munitions factory. In May 1946, he was given his release papers, sent to New York, and put on a ship for Germany. How great his disappointment must have been when the ship was not allowed to dock in Germany but was turned back to Rotterdam in the Netherlands. From there he was sent to Belgium. While he awaited his release, he nearly starved, losing sixty pounds. “They gave us nothing to eat. I went to the bathroom once in four weeks. I will never forget that,” he explained.

By the late summer of 1947, Lothar had been moved back to England. After three years of no mail from home, he was still unaware of the fate of his family, but a letter from his sister finally reached him. She wrote that their father, political prisoner Hans Emil Flade, had been killed in Berlin on the last day of the war. Apparently he had been found dead with a piece of shrapnel embedded in his right forehead.

For more than four years, young Lothar had been isolated from the Church. A deacon, he had no scriptures, no opportunity to partake of the sacrament, no interaction with LDS soldiers—nothing but prayer. The first contact came in 1947. A relative had written to the office of Ezra Taft Benson in London and asked that a missionary be sent to visit Lothar. He was working in the beet harvest that fall near Cambridge when a letter arrived from Elder Benson. The missionary arrived just before Lothar was released, thus he never had a chance to attend Church services in England. He arrived in Chemnitz in late November 1947.[26]

Shortly after the war, Charlotte Popitz Ficker learned that her husband was a prisoner of war under the Americans in southern Germany. Although he was less than two hundred miles away from Chemnitz, she could not visit him. He finally returned to her in 1950.

Regarding the way the Saints in Chemnitz reacted to the trials of wartime, Henry Burkhardt made the following observation:

During this hard time of the war, inactive or less-active members of the Church came back and joined us again. Nobody became less active or fell away from the Church. We all looked for something to hold on to. We held our baptismal services in the little Chemnitz River or in a little basin provided by [the Heidler] family. The sacrament was passed in both Sunday School and sacrament meeting.

The Chemnitz Center Branch lost at least fifty of its members during World War II—more than any other branch in the East German Mission. Nevertheless, the survivors went right to work after the war to find a new place to hold meetings and to carry out the work of the Church.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Chemnitz Center Branch did not survive World War II:

Paul Auerswald b. Neuschönburg, Zwickau, Sachsen 3 Jan 1894; son of Alban Auerswald and Hulda Emilie Meinhold; bp. 17 Sep 1927; conf. 17 Sep 1927; ord. deacon 2 Sep 1928; ord. teacher 2 Jun 1929; ord. priest 6 Apr 1930; ord. elder 19 Oct 1931; m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 15 Feb 1916, Elsa Erna Tanzmann; 2 children; 2m. 16 Mar 1945; d. 1945 (CHL, LR 4326 22, No. 1; IGI)

Walter Bergmann b. Chemnitz, Saxony 1 May 1897; m. 29 Apr 1920, Marie Erna Neuschrank; 5 children; sergeant; d. POW camp, Deutsch-Eylau 31 May 1945; bur. Ilawa, Poland (Poppitz-Ficker; [author: all the other ones say “Puppitz-Ricker” Is it also the Popitz Ficker of the text?] IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Richard Alfred Burkhardt b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 20 Mar 1922; son of Max Richard Burkhardt and Johanna Else Müller; bp. Chemnitz 18 Aug 1930; conf. Chemnitz 18 Aug 1930; MIA Dec 1941 by Leningrad, Russia (H. Burkhardt; IGI)

Alfred “Fred” Burkhardt (H. Burkhardt)

Alfred “Fred” Burkhardt (H. Burkhardt)

Lothar Alfred Cieslak b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Jul 1927; son of Alfred Otto Cieslak and Leopoldina Rosalie Ottilie Leibner; bp. 10 Aug 1935; k. in battle Western Front 2 Apr 1945; bur. Soldatenfriedhof Bensheim, Hessen (Hyrum Cieslak; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Herbert Emil Derr b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 22 Nov 1909; son of Emil Derr and Hulda Olga Spindler; bp. 11 May 1918; m.; seaman first class; k. in battle Clisson, Nantes, France 13 Aug 1944; bur. Pornichet, France (www.volksbund.de; IGI)

Ida Minna Eckhardt b. Gablenz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 14 Jul 1865; dau. of Karl Friedrich Eckhardt and Amalie Wilhelmine Gebhardt; bp. 29 Aug 1925; conf. 29 Aug 1925; m. Gablenz 27 Nov 1887, Markus Max Seifert; 9 children; d. stroke Erdmannsdorf, Chemnitz, Sachsen 29 Sep 1939 (CHL LR 1932 21, No. 179; IGI; AF; PRF)

Karl Falkner: b. Nurnberg, Mittelfranken, Bayern 14 Jun 1885; son of Paul Heinrich Falkner and Anna Katharina Lauterbach; bp. 14 Nov 1925; m. 1 Nov 1907, Ida Klara Taubert; 5 children; 2m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Sep 1926, Lina Ella Tierlich; 3 children; 3m. Helene Mehnert; d. illness Chemnitz 22 Dec 1944 (H. Falkner-Pippig; IGI; AF)

Bruno Max Fischer b. Oberwiesenthal, Chemnitz, Sachsen 15 Apr 1881; son of August Ehregott Fischer and Louise Auguste Seltmann; bp. 17 Mar 1923; conf. 17 Mar 1923; ord. deacon 9 Nov 1924; ord. teacher 25 Apr 1926; ord. priest 31 Aug 1931; m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 29 Mar 1909, Johanna Emma Roggenbau; 4 children; k. air raid Chemnitz 5 Mar 1945 (E. Goeckeritz; CHL LR 1632 21, No. 131; IGI; AF)

Elisabeth Linda Fischer b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 24 Apr 1919; dau. of Bruno Max Fischer and Johanna Emma Roggenbau; bp. 14 May 1927; conf. 14 May 1927; m. Annaberg, Chemnitz, Sachsen 13 Mar 1943, Joachin Karl Heinrich Haensel; k. air raid Chemnitz 5 Mar 1945 (CHL LR 1632 21, No. 136; IGI; AF)

Erika Johanna Fischer b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 16 Jun 1916; dau. of Bruno Max Fischer and Johanna Emma Roggenbau; bp. 23 Jun 1924; conf. 23 Jun 1924; m. Chemnitz 30 Sep 1939, Albrecht Hugo Hellmut Lohberger; 2 children; k. air raid Chemnitz 5 Mar 1945 (CHL LR 1632 21, No. 135; IGI)

Emil Hans Flade b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 18 Sep 1892; son of Ernst Emil Flade and Amalia Ida Schroeder; bp. 20 Jun 1925; ord. elder; m. Chemnitz 15 Jul 1914, Paula Hulda Musch; 2 children; police trainee; k. in battle Wedding, Berlin, Preussen Apr or May 1945 (J. Flade; www.volksbund.de; FHL Microfilm 25767, 1930/

Helmut Bruno Fleming b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 12 Jul 1911; son of Bruno Paul Fleming and Flora Minna Hoeppner; bp. 12 Jul 1927; k. in battle 1945 (Puppitz-Ricker; IGI)

Waldemar Fleming b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 29 Nov 1914; dau. of Bruno Paul Fleming and Flora Minna Hoeppner; bp. 5 Jun 1927; d. in asylum (euthanasia?) 1941 (Puppitz-Ricker; IGI)

Selma Liddi Froede b. Zug 4 Jun 1883; dau. of Emil Froede and Pauline Kinden; bp. 31 Jan 1920; conf. 1 Feb 1920; m. 7 May 1935, Fritz Junghanns; k. air raid 8 Mar 1945 (CHL, LR 4326 22, No. 201; IGI)

Joseph Johann Frohm b. Erlangen, Mittelfranken, Bayern 15 Oct 1862; son of Josef Haberich and Theresie Frohm; bp. 8 May 1907; conf. 8 May 1907; ord. elder 13 Oct 1929; m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 12 Feb 1890, Minna Wilhelmine Prell; 2 children; d. old age Chemnitz 24 Mar 1942 (CHL LR 1932 21, No. 326 or 576; IGI; AF)

Helene Anna Frosch b. Dittersdorf, Germany 9 Feb 1878; dau. of Friedrich Frosch and Anna May; m.—Herrmann; d. 6 Feb 1945 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1394–95)

Karl Albert Göckeritz b. Lössnitz, Freiberg, Dresden, Sachsen 1 Nov 1909; son of Max Karl Goeckeritz and Minna Emilie Enderlein; bp. 2 Sep 1919; ord. elder; Chemnitz district president; m. 14 Mar 1934, Magdalena Johanne Derr; 3 children; MIA near Stalingrad, Russia Jan 1943 (Karl-Heinz Goeckeritz; Harald Goeckeritz; IGI)

Joachim Karl Heinrich Haensel b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Jun 1919; son of Karl Oscar Haensel and Flora Martha May; bp. 13 Oct 1927; conf. 13 Oct 1927; ord. deacon 1 Nov 1931; m. Annaberg, Chemnitz, Sachsen 13 Mar 1943, Linda Elisabeth Fischer; policeman; k. in battle Streindorf, Italy 12 Feb 1945; bur. Kranj, Slovenia (www.volksbund.de; CHL LR 1933 21, No. 76 or 356; IGI)

Heinz Hänsel (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

Heinz Hänsel (E. Goeckeritz McClellan)

Erich Lothar Hauck b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 24 Jan 1904; son of Emil Robert Haugk and Hulda Lina Leonhardt; bp. 24 Jul 1926; conf. 24 Jul 1926; ord. deacon 18 Feb 1929; m. 21 Apr 1934, Charlotte Elfriede Goeckeritz; k. in battle 23 or 25 Mar 1945 (CHL, LR 4326 22, No. 144; IGI; Puppitz-Ricker)

Martha Heymann b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 18 Mar 1889; dau. of Franz Louis Heymann and Johanne Christiane Friedericke Doelling; bp. 18 Mar 1910; d. 3 Dec 1941 (K. Göckeritz diary; FHL Microfilm 162783, 1935 Census; IGI; AF)

Erich Walter Hinkel b. Frankenstein, Chemnitz, Sachsen 24 Nov 1911; son of Karl Friedrich Hinkel and Bertha Emma Dietrich; bp. 15 Jul 1922; corporal; k. in battle 22 or 24 Apr 1945; bur. Bad Überkingen, Württemberg (CHL Microfilm No. 2458, form 42 FP, Pt. 37, 1394–95; IGI; AF; www.volksbund.de)

Martha Helene Hoeppner b. Chemnitz 2 Dec 1887; dau. of Friedrich H. Hoeppner and Marie Helene Herzog; d. tumor 6 Mar 1945 (CHL CR 375 8 #2460, 258–59)

Elsa Elisabeth Jung; b. Waldheim, Chemnitz, Sachsen 12 Mar 1902; dau. of Ernst Emil Jung and Anna Helene Otto; bp. 22 Aug 1931; m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 14 May 1927, Hermann Otto Tutzschky; 2 children; 2m. Chemnitz, Helmut Otto Süss; 5 children; arrested Chemnitz 2 Sep 1942; k. in Ravensbrück Concentration Camp, Ravensbrück, Brandenburg, Preussen 25 Jan 1945 (W. Süss; Puppitz-Ricker; IGI; AF; PRF)

Rudolf Kurt Lehmann b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 17 Jun or Jul 1917; son of Ernst Kurt Lehmann and Marie Gertrud Leevig; bp. 5 Nov 1927; conf. 5 Nov 1927; ord. deacon 6 Mar 1932; m. 27 Feb 1941, Gertrud Elfriede Oberländer; lieutenant; k. in battle west of Gamasza, Hungary 6 Mar 1945 (CHL, LR 4326 22, No. 237; IGI; Puppitz-Ricker; FHL Microfilm 271386, 1930/

Ida Wilhelmine Loerner b. Leitz, Thüringen 20 Jun 1870; dau. of Karl Robert Loerner and Karoline Gutenberg; bp. 25 Apr 1925; conf. 25 Apr 1925; m. 2 Mar 1889, Hugo Schmutzler; d. weakness 18 Apr 1940 (CHL LR 1932 21, No. 295 or 545)

Albrecht Hugo Hellmut Lohberger b. Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Chemnitz, Sachsen 23 Aug 1915; son of Ernst Hugo Lohberger and Elsa Anna Mueller; bp. 7 Mar 1928; m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 30 Sep 1939, Erika Fischer; 2 children; Senior Lance-Corporal or Private 1st Class (Obergefreiter); d. Russia OR Raczynk, Poland 23 Aug 1944; bur. Opechowo, Poland (Puppitz-Ricker; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Heinz Jürgen Lohberger b. Chemnitz May 1944; son of Albrecht Hugo Hellmut Lohberger and Erika Johanna Fischer; k. air raid Chemnitz 5 Mar 1945 (IGI)

Peter Hellmut Lohberger b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 7 Oct 1940; son of Albrecht Hugo Hellmut Lohberger and Erika Johanna Fischer; k. air raid Chemnitz 5 Mar 1945 (IGI)

Auguste Luisa Melzer b. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 13 Nov 1851; dau. of Karl August Melzer and Amalie Rudolph; bp. 6 Aug 1920; conf. 8 Aug 1920; m. 29 Jun 1890, Carl Gustav Hahmann; d. old age Apr 1945 (CHL LR 1632 21, No. 105; IGI)

Elsa Anna Mueller b. Hohenstein-Ernstthal, Chemnitz, Sachsen 22 Feb 1885; dau. of Ernst Louis Mueller and Wilhelmine Auguste Peenert; bp. 5 Nov 1927; m. Hohenstein-Ernstthal 24 Dec 1906, Ernst Hugo Lohberger; 5 children; 2m. 17 Nov 1923,—Mueller; k. air raid Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 5 Mar 1945 (IGI)

Emma Marie Muesch b. Sebastiansberg, Chemnitz, Sachsen 18 Dec 1884; dau. of Johann Anton Muesch and Karoline Sidonia Schlottig; bp. 24 Jul 1926; conf. 24 Jul 1926; m. 14 Dec 1929, Paul Kuehnel; d. intestinal cancer 25 Oct 1941 (CHL LR 1932 21, No. 187; IGI)

Martha Frieda Peter b. Ringthal, Mittweida, Sachsen 19 Aug 1901; dau. of Otto Friedrich Peter and Lina Bertha Leutert; bp. 10 Sep 1927; conf. 10 Sep 1927; m. Mittweida, Leipzig, Sachsen 24 Dec 1921, Martin Johannes Donner; 3 children; d. heart ailment Claussnitz, Leipzig, Sachsen 12 Dec 1940; bur. Claussnitz (Sonntagsgruss, No. 15, 13 Apr 1941, 60; CHL LR 1932 21, No. 208 and LR 4326 22, No. 55; IGI)

Johannes Gerhardt Poppitz b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 2 Jul 1914; son of William Gerhardt Poppitz and Johanne Helene Baum; bp. 2 Jul 1922; MIA Russia 1944 (Puppitz-Ricker; IGI)

Edwin Alfred Preissler b. Borstendorf, Chemnitz, Sachsen 30 Jun 1888; son of Ernst Emil Preissler and Anna Emma Richter; bp. 26 Jul 1923; conf. 26 Jul 1923; ord. deacon 9 Nov 1924; ord. teacher 25 Apr 1926; ord. priest 26 Mar 1928; ord. elder 1 Dec 1929; m. Borstendorf 9 Jul 1911, Maria Elsa Hunger; 5 children; d. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 22 Apr 1940 (CHL LR 1932 21, No. 139; Sonntagsstern, No. 17, 26 May 1940 n. p.; IGI; AF)

Kurt Alfred Preissler b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 17 Mar 1913; son of Edwin Alfred Preissler and Marie Elsa Hunger; m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Dec 1937, Kaethe Hildegard Haehle; 1 child; k. in battle 1943 (Puppitz-Ricker; IGI; AF)

Ida Alma Reichel b. Obernhau [?], Germany 11 Jun 1868; dau. of August Reichel; m.—Braumann; d. old age 24 Sep 1940 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1394–95)

Anna Reissmann b. Geyer, Chemnitz, Sachsen 14 Aug 1866; dau. of Martin Reissmann and Auguste L. Dessauer; bp. 17 Mar 1926; d. 30 Jan 1940 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1394–95)

Marie Helene Richter b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 22 Feb 1877; dau. of Julius Richter and Clara Schubert; d. 8 Oct 1942 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1394–95)

Heinz Otto Rieck b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 28 Sep 1917; m. Chemnitz 4 Oct 1941, Rahel Regina Theodora Göckeritz; MIA near Leningrad, Russia 1 Jan 1944 (Poppitz-Ficker; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Johanna Emma Roggenbau b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 1 Feb 1889; dau. of Hans Friedrich Gustav Arnold Roggenbau and Emma Emilie Hunger; bp. 15 Oct 1921; conf. 15 Oct 1921; m. Chemnitz 29 Mar 1909, Bruno Max Fischer; 4 children; d. air raid Chemnitz 5 Mar 1945 (CHL LR 1632 21, No. 132; IGI; AF; PRF)

Guido Guenther Scheithauer b. Chemnitz 6 Oct 1922; son of Martha Marie Loose; k. in battle (Puppitz-Ricker; FHL Microfilm 245258, 1930 Census)

Martha Elise Schreiber b. Buchholz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 29 Feb 1912; dau. of Moritz Schreiber and Anna Martha Lang; d. diabetes 16 Jan 1945 (CHL CR 375 8 #2460, 258–59)

Markus Max Seifert b. Erdmannsdorf, Chemnitz, Sachsen 20 Mar 1864; son of Friedrich Fuerchtegott Seifert and Juliane Dorothea Emmerich; bp. 28 Jul 1930; m. Gablenz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 27 Nov 1887, Ida Minna Eckhardt; 9 children; d. Erdmannsdorf 18 Mar 1944 (IGI; AF; PRF)

Jutta Monika Suess b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 15 Sep 1940; d. 2 Jun 1942 (W. Suess) [author: is this the same guy as in the next paragraph?]

Helmut Otto Süss b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 26 Feb 1913; son of Georg Walther Suess and Marie Agnes Lindner; bp. 3 Oct 1931; conf. 9 Oct 1931; ord. deacon 30 Nov 1932; m. Chemnitz 28 May 1934, Elsa Elisabeth Jung; 5 children; lance corporal; k. in battle Baumeles Dames, Doubs, France 5 Sep 1944; bur. Andilly, France (W. Süss; Poppitz-Ficker; CHL LR 1933 21, No. 233 or 509; IGI, www.volksbund.de)

Helmut Otto Süss (W. Süss)

Helmut Otto Süss (W. Süss)

Elsa Erna Tanzmann b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 2 or 25 Sep 1895; dau. of Kurt Reinhard Tanzmann and Liba Henriette Schumann; bp. 17 Sep 1927; conf. 17 Sep 1927; m. Chemnitz 15 Feb 1916, Paul Auerswald; 2 children; d. lung ailment Chemnitz 9 Jan 1945 (CHL, LR 4326 22, No. 4; IGI)

Lina Ella Tierlich b. Gablenz, Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Feb 1900; dau. of Heinrich Franz Tierlich and Lina Anna Taubert; bp. 17 Mar 1926; m. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Sep 1926, Karl Falkner; 3 children; d. Chemnitz 7 Jan 1944 (H. Falkner-Pippig; FHL Microfilm 245258, 1930 Census)

Manfred Alexander Vettermann b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Apr 1916; son of Emil Max Vettermann and Emma Margarete Franke; bp. 10 Apr 1925; k. in battle in the West 5 Jan 1945 (Puppitz-Ricker; IGI; AF)

Walter Emil Vettermann b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 7 Jul 1911; son of Emil Max Vettermann and Anna Margarete Franke; railroad policeman; k. on the Slutsk—Minsk Railway, Belarus 27 Jun 1944; bur. between Slutsk and Minsk, Belarus (Poppitz-Ficker; IGI; AF; www.volksbund.de)

Anna Marie Vogelsang b. Krumbach, Leipzig, Sachsen 9 Mar 1893; dau. of Karl Moritz Vogelsang and Auguste Theresia Thuemer; bp. 21 Oct 1919; conf. 22 Oct 1919; k. air raid Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 5 Mar 1945 (I. Franke Böttcher; CHL LR 1632 21, No. 91; IGI; AF)

Amalie Auguste Wittig b. Zöblitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 4 Jun 1867; dau. of Friedrich Moritz Wittig and Christiane Friedricke Uhlmann; bp. 2 Sep 1919; m.—Claus; d. 11 Mar 1944 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1394–95)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Ilse Franke Böttcher, interview by the author, Idaho Falls, Idaho, June 10, 2006.

[3] Henry Burkhardt, interview by the author in German, Leipzig, Germany, June 2, 2007. Unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski, and audio version or transcript of the interview in the author’s collection.

[4] Herbert Heidler, interview by the author in German, Leipzig, Germany, June 2, 2007.

[5] John (Johannes Lothar) Flade, interview by the author in German, South Jordan, Utah, February 10, 2006.

[6] Heinz Albert Bonitz, telephone interview by Judith Sartowski, May 2, 2008.

[7] Alfred P. R. Schulz, papers, 1921–1950, MS 8242, Church History Library.

[8] Brunhilde Falkner Pippig, telephone interview by Jennifer Heckman in German, February 15, 2008.

[9] Siegfried Donner, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, February 2, 2007.

[10] Hyrum Cieslak, interview by the author in German, South Jordan, Utah, January 17, 2008. Of course, not only LDS parents tried to keep their children from becoming involved in Hitler Youth activities. Many Germans were opposed to such programs for political, religious, or cultural reasons.

[11] Irene Härtel Schönfeld, interview by the author in German, Jahnsdorf, Germany, May 29, 2007.

[12] Richard Burkhardt to Fred Burkhardt, letter, November 16, 1941; private collection; trans. the author.

[13] Sigrid Cieslak Rudolph, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, January 17, 2008.

[14] G. Wolfgang Süss, autobiographical report, April 22, 2006; author’s collection.

[15] Hanna Süss-Benten, interview by the author in German, Friedrichsdorf, Germany, August 7, 2006.

[16] Karl Göckeritz, diary, July 1936; private collection; trans. the author.

[17] John Flade, autobiographical report; private collection.

[18] Charlotte Popitz Ficker, interview by the author in German, Nuremberg, Germany, August 13, 2006.

[19] Irene Härtel Schönfeld, interview by the author in German, Jahnsdorf, Germany, May 29, 2007.

[20] See the description of the Waffen-SS (elite combat troops) in the introduction.

[21] Irmgard Susanne Flade Groebs Staufenbeil, interview by Michael Corley in German and English, Salt Lake City, January 25, 2008.

[23] See the Hohenstein chapter for additional details.

[24] Reiner Gröbs, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, January 19, 2007.

[25] Karl Heinz Goeckeritz, interview by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, February 8, 2008.

[26] The date was likely May 2, the last day of fighting in Berlin, rather than the last day of fighting in Europe, which was May 7.