Breslau West Branch, Breslau District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 136-42.

With 265 members, the Breslau West Branch was the tenth largest in all of Germany in 1939. The meetings rooms were located at Westendstrasse 50 in the western suburb of Breslau known as Nicolai-Vorstadt. Werner Hoppe (born 1934) later described the setting:

| Breslau West Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 16 |

| Priests | 16 |

| Teachers | 11 |

| Deacons | 17 |

| Other Adult Males | 46 |

| Adult Females | 134 |

| Male Children | 12 |

| Female Children | 13 |

| Total | 265 |

The branch building was interesting; it was located above the movie theater. It was a big hall that smelled of beer and smoke, but we cleaned it up. We had classrooms and restrooms. The room may have been used for other things during the week. We entered the room from the back. There were no pews, just chairs. There was a stage. We had to do a lot of cleaning. We always met in those rooms throughout the war. I do not recall any damage to the building; if it happened, it was after we left [in 1944].[2]

Ruth Gottwald (born 1929) recalled the following about the rooms there:

We had lots of activities there because the room and the stage were large. And we had district conferences there. Primary and MIA were held during the week. We had sports and lots of stuff. It seemed like there was something going on [at the church] every day.[3]

Kurt Mach (born 1915) was interested in flying, so he joined a flying club in the 1930s. He also qualified for a driver license—a rarity in those days. In 1935, Hitler’s government expanded the Reichsarbeitsdienst program and introduced universal military conscription. Kurt was the perfect candidate for national service. He spent six months of 1936 building roads and planting trees in a beautiful section of his native province of Silesia before being drafted into the air force in April 1937.[4]

During his basic training term, Kurt was stationed in Nordhausen (north-central Germany) and was pleased to join with the very small group of Latter-day Saints in a basement apartment to worship when his schedule permitted. “A marvelous spirit filled the seven to eight members there,” he later wrote.

In August 1939, the month prior to the beginning of World War II, Kurt was injured on the job and classified as unfit to fly. This led to an assignment with air traffic control, and he was initially stationed near the German-Soviet demarcation line in occupied Poland. Engaged since 1939, he was granted permission to marry on May 30, 1940. The civil registrar was actually a farmer who performed the service voluntarily. His conduct was so unpolished that “we had a hard time suppressing our laughter.” His bride was Elisabeth Nowak, not yet a member of the Church, and they had little time to celebrate: he was called back to duty prematurely because Germany had launched several offensives in western and northern Europe.

Kurt Mach was to have shipped out to France in June 1940, but he contracted an infection in his hands while handling munitions and remained near home in Breslau-Zimpel for treatments for the next six months. In 1941, his health deteriorated and he was released from the military but immediately assigned to civilian service with the air force. By the end of that year, two monumental things had occurred: his wife had given birth to a little girl, and Germany had attacked the Soviet Union. Kurt was grateful to be home with his family.

Young Werner Hoppe was baptized in the Oder River on his eighth birthday—August 28, 1942. His entire family attended the ceremony, along with a few members of the branch. Soon thereafter, his father, district president Martin Hoppe, was transferred to the Eastern Front, where he continued to serve the Wehrmacht as a translator.

As the war entered its third year in late 1941, members of the branch wished to preserve the memory of their fallen soldiers. According to Werner Hoppe,“I remember a memorial, a large poster, with the names of the brethren killed during the war, displayed in our meeting rooms. We kept holding meetings all the time [my family] was there, but there were fewer and fewer men in attendance.”

Ruth Gottwald experienced a personal tragedy in 1943, as she later explained:

My father was not a member of the Church. In 1943, he apparently deserted and came home and didn’t want to be in the army anymore. So he was at home for a few weeks, then they took him to the prison at Landsberg/

Warthe and executed him by firing squad. His mother was allowed to visit him there and was told that he was to be shot. They refused to take me there to visit him because they didn’t want me to be exposed to the situation. They didn’t want me to be ostracized at school. They told me that he refused to eat toward the end but just smoked cigarette after cigarette. He just didn’t want to be a part of it anymore.

His death left Ruth and her mother on their own to survive the last two years of the war.

As the air raids over Breslau began to make the city a very unsafe place to live, Ruth Gottwald and her mother sought refuge in the basement of the building where Sister Paula Hubert lived. Ruth recalled studying the Book of Mormon in that basement. The Gottwalds’ apartment building survived the war, but their windows all burst from the air pressure caused by the exploding bombs, and there was an enormous bomb crater right in front of the building.

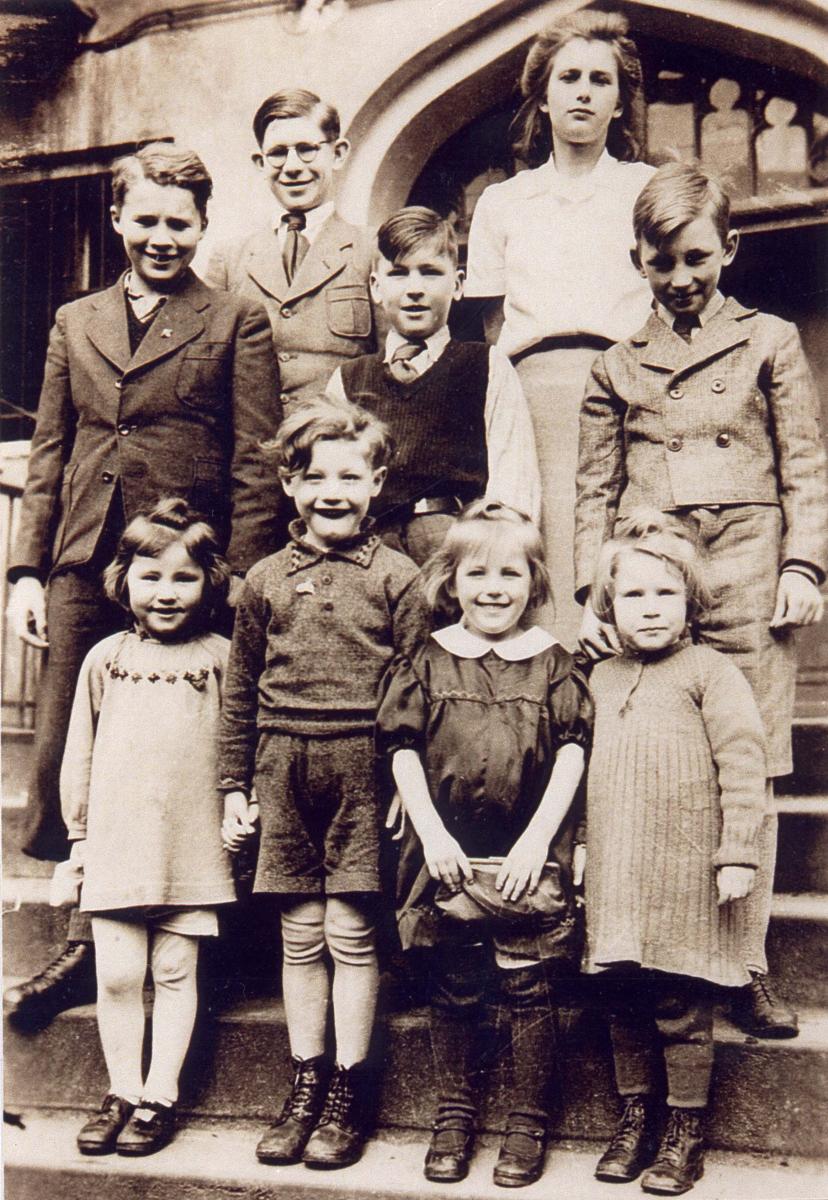

Youth of the Breslau West and Breslau Center Branches (front row from left: Brunhilde Hoppe, Werner Hoppe, Renate Müller, Bruni Deus; middle row: Rudi Nolte, Manfred Deus, Joachim Müller; back row: Werner Nitschke, Edith Müller) (W. Hoppe)

Youth of the Breslau West and Breslau Center Branches (front row from left: Brunhilde Hoppe, Werner Hoppe, Renate Müller, Bruni Deus; middle row: Rudi Nolte, Manfred Deus, Joachim Müller; back row: Werner Nitschke, Edith Müller) (W. Hoppe)

The health problems that left Kurt Mach unfit for active military duty were not severe enough to spare him from serving in the fruitless effort of repelling the Red Army invasion of Germany that began in late 1944. He was drafted in November and sent to a defensive position about twenty miles from Warsaw, Poland. Later, he was sent to Czechoslovakia to be trained in the use of antitank weapons. From there he was able to visit his family in Breslau from January 11 to 13, 1945. Six days later, he returned to the Eastern Front and was captured there by the Soviets.

In the late summer of 1944, Gertrud Hoppe took her three children and left Breslau, following the city government’s recommendation that women take their children to safer locations. For several months, the Hoppes lived with relatives in a small town near the Polish border. In January 1945, they returned to Breslau, just in time to join the exodus of civilians from the city that was soon surrounded by the Soviets. A train then took Sister Hoppe and her children through Czechoslovakia to Austria.

The Martin Hoppe family of the Breslau West Branch (L. Hoppe)

The Martin Hoppe family of the Breslau West Branch (L. Hoppe)

In January 1945, Kurt Mach’s wife, Elisabeth, was informed that all women and children were to leave Breslau. While she was gathering a few critical items in her basement, she had left her little girls in the apartment upstairs. Suddenly, she heard a voice say, “Go upstairs!” but she looked around and nobody was there. Twice more the same message was audible and seemed to be more urgent. She dropped everything, raced up two flights of stairs, and found her baby daughter choking on a piece of cotton. As she later recalled:

With lightning speed, I tore the stuff out of her mouth and she took a deep breath. I was paralyzed with fear but recovered quickly. I lifted her from the carriage, held her in my arms, and wept. . . . All I could say was, “Thank you, dear Lord, thank you, dear Lord.”[5]

Trying to board an overcrowded train heading west, Elisabeth Mach was pushed back by desperate crowds of refugees. Nobody was willing to help her get the stroller into the train. At one point, three-year-old Karin was nearly pushed under the wheels of the train. When the train was about to depart, Elisabeth Mach was still standing there with two little daughters. Fortunately, the conductor learned of her dilemma. He was able to find a spot in a different car and helped her load the stroller into the train. They made their way to Weisswasser, near Torgau on the Elbe River, where they waited for word from their father, Kurt.

The Gottwalds delayed their departure from Breslau until it was too late. Ruth had been serving coffee and tea to refugees at the main railroad station, and she and her mother were not prepared to leave the city by train. They then chose the next best option, as she later explained:

We had a sleigh that we loaded up and got out just before the city was totally surrounded. There was so much snow. We went about 45 minutes into the forest outside of town. We saw many people who had hanged themselves in the trees. My mother said that we couldn’t survive in those conditions, so we returned to the city.

Ruth Nestripke (born 1925) also tried to leave Breslau with the first wave of evacuees. She was especially offended by the political leaders who provided no means of transportation and no suggestions as to where to go:

When we asked the political bosses where we should go and how we should transport ourselves, they mocked us with the response: “You have feet! Or would you prefer that we carried you?” They called us Volksschädlinge [public liabilities] because we didn’t want to leave and therefore hindered their attempts to defend the city. . . . [They threatened that] whoever didn’t leave the city by the next day at 10 a.m. would be shot on sight, but that didn’t work, either.[6]

Temperatures approached zero, and many who left town froze to death, while others simply gave up any hope of fleeing and returned to the city.

Back in Breslau, living conditions steadily deteriorated. One day, as enemy fighter planes sprayed bullets through the streets, Ruth Nestripke and her aunt ran inside a dairy store for shelter. Ruth fell down, reached for her aunt, and clung tightly to her. When the danger was past, she found that she was holding on to a dead German soldier. “You can imagine what I thought when I saw his face that reflected suffering and death,” she recounted.[7]

A few weeks later, Ruth was hit by shrapnel from Red Army artillery. The metal left a hole nearly two inches in diameter on one side of her thigh and nearly three inches on the other side. Fortunately, Brother Zelder from the Breslau South Branch came by and was able to secure medical treatment for her. “I ground my teeth together because the pain was so intense, but I didn’t want my dear mother to worry about me.”[8]

Ruth Nestripke had to be taken to see the doctor every day for weeks because the wound did not heal. One day, he told her that she had to work to straighten her leg or else she would lose her ability to do so; the metal had torn her tendon. Shortly thereafter, she was looking out her window when a party official saw her and yelled: “Why aren’t you out building street barricades?” “I’m wounded!” “That’s what they all say!” he retorted. She was not surprised when a few minutes later, a soldier came by to arrest her but realized the error and quickly left with the excuse, “I’m just following orders.”[9]

Stranded in Breslau, the Gottwald women were put to work helping to defend the city. Ruth described the situation in these words:

We had to help dig out trenches for the soldiers. They retreated bit by bit and that was really scary. . . . Any time there was a pause in the bombing, people hurried to the stores to try to get something to eat. Then the dive bombers came and shot people in the streets. We didn’t dare go outside. . . . Outside there were dead people all over and huge piles of rubble.

By March 1945, the Gottwalds were living downtown and had lost all contact with the Breslau West Branch on Westendstrasse.

By the time the city capitulated on May 6, 1945, many of the buildings had been reduced to rubble. What happened when the Red Army entered the city was, according to Ruth Nestripke, “worse than what we went through during the siege. The Russians were like animals. In fact, they were worse because they disregarded all intelligence and reason.” The Polish came later and continued to rob and assault the civilians. In many cases, they evicted people from their homes with as little as ten minutes’ warning.[10]

Rudi Nolte in the uniform of the Reichsarbeitsdienst (C. Kleist Nolte)

Rudi Nolte in the uniform of the Reichsarbeitsdienst (C. Kleist Nolte)

In October 1945, the Gottwalds were evicted from their apartment by the new Polish government. “Overnight we had to leave. We had one afternoon to pack and the next morning we had to leave.” They took the train west to Liegnitz, then began a disorganized exodus west to Germany. Traveling with them was an uncle who was looking for his family along the way. When they reached Muskau at the new Polish-German border, they were detained. Ruth recounted the events years later:

At Muskau one morning (it was dark, about 5 a.m.) a man showed us the way to cross the border secretly. We were caught by two Russians and they took my backpack. I had 500 marks rolled up in a blanket and they took that and they took my uncle’s last blanket. My uncle had some Church books and some paper money in the books. They took us to a guard station and kept the books overnight. They asked if those were church books, and they gave them back the next morning. They didn’t find the money. Then we walked to the border, through the no-man’s-land, and my uncle started to sing: “O Babylon, O Babylon, we bid thee farewell!”

Once back in Germany, the Gottwalds made their way to Cottbus to join the colony of refugee Saints at the Fritz Lehnig home. There was no room for them there so they were sent to the new Church refugee colony at Wolfsgrün, south of Zwickau. Looking back on their terrible experiences in Breslau at the end of the war, Ruth said:

We never doubted God. That was our salvation, our faith. He protected us. I had grown up in the Church and was blessed. I just kept hoping that we would survive, and He saved us. We always believed in God. . . . The Church was our only salvation. What would we have done without the Church?

Following a bout with dysentery that lasted three months, Kurt Mach was close to death in a Soviet prison camp. Thirty-five to fifty German prisoners were dying of diseases in that camp every day, but death was also the punishment for anybody attempting to record their names. With the end of the war on May 8, 1945, transfers of the prisoners to points farther east began. By September, Kurt was in Pulavy but was considered so unfit for physical labor that he was released by his captors. On September 29, he began the trek home. He somehow survived (though other Germans were dying in great numbers around him) and made it to eastern Germany.

Similar to millions of Europeans, Kurt searched in many offices in the Soviet occupation zone for information about his family. After finding employment in Sömmerda, he began writing letters to relatives to learn the whereabouts of his wife and his daughters (Karola was born in 1944). On December 4, 1945, he received a card informing him that they were in Torgau, a few hours to the north. The reunion was a bit confusing, as he recalled: “Of course I was a changed man. Just a week before my release, they shaved me bald again. We had lost all of our possessions, but we were alive.” He then took his family back to Sömmerda.

After arriving in Austria, Getrud Hoppe was fortunate to find a group of Austrian Latter-day Saints in Haag am Hausruck near Salzburg. The family stayed there for four years then moved across the border into Germany. Looking back on those times, daughter Brunhilde Hoppe decided that she was glad to have been just a young girl during the war: “I was glad that I was not an adult or a mom in the war years because it would be especially hard if you had children then.”

By the fall of 1946, all of the surviving members the Latter-day Saint Breslau West Branch had left the city that would be called Wrocław, Poland, and the branch disappeared into history.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Breslau West Branch did not survive World War II:

Anna Pauline Galle b. Sacherwitz, Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 19 Sep 1849; dau. of Gottfried Galle and Johanna Theresia Schmidt; bp. 12 Jun 1908; m. Christian Lerche; 8 children; d. senility 29 Nov 1939 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1939 data; IGI)

Mannfred Hendriock b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 3 Aug 1926; son of Walter Fritz Hendriock and Lisbeth Frieda Auguste Bollach; k. in battle Russia 2 May 1945 (R. Nolte; IGI)

Martin Werner Hoppe b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 10 Oct 1906; son of Otto Martin Paul Hoppe and Emma Anna Ida Schwarz; bp. 15 Dec 1914; m. Nov 1933; 4 children; Breslau District President; corporal; d. Krgsl. 926 mot. Uman, Ukraine, USSR 23 Oct 1943 (A. Langheinrich; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Karl August Kruber b. Schmograu, Schlesien, Preussen 6 Jan 1875; son of Johann Gottlieb Kruber and Christiane Skupin; bp. 10 Jul 1927; m. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 21 Feb 1910, Emilie Anna Marie Winkler; 5 children; d. cancer Breslau 30 Sep 1939 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1939 data; IGI)

Johanna Pauline Moschinsky b. Olschina, Posen, Preussen 19 Feb 1848; dau. of Karl Moschinsky and Friedricke Drescher; bp. 26 Jan 1910; m.—Pola; d. Spalitz, Breslau, Schlesien 3 May 1942 (FHL Microfilm 271394, 1935 Census; IGI)

Richard Alfred Pola b. Spahlitz, Oels, Schlesien, Preussen 19 Oct 1910; son of Ernst Wilhelm Pola and Pauline Mosch; bp. 13 Sep 1920; m. 30 Jun 1941; d. 1 Jul 1941 (FHL Microfilm 271394, 1935 Census; IGI; AF)

Renate Susanne Runge b. Bürgsdorf, Kreuzburg, Schlesien, Preussen 17 Nov 1914; dau. of Paul Wilhelm Runge and Marie Goy; bp. 6 Jun 1925; d. in childbirth Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 5 May 1941; bur. Breslau-Mochbern 8 May 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, No. 23, 8 Jun 1941, p. 92; IGI)

Fritz Alfred Uebrick b. Kaltenbrunn, Schweidnitz, Sachsen, Preussen 20 Mar 1909; son of Paul Johann Übrick and Erna Pauline Klammt; bp. 28 May 1921; lance corporal; d. POW Frolowo, Russia 10 Jul 1944; bur. Sebesh, Russia (F. Tietze; FHL Microfilm 245289, 1925/

Hermann Walter b. Saint Petersburg, Russia, USSR 9 Feb 1896; m. Doberan, Livland, Estonia, USSR 6 Jul 1922, Ursula Kliefoth; 2m. Berlin Lichtenberg, Preussen 5 Dec 1939, Sigrid Hansen; d. Berlin 7 Jan 1945 (SLCGW; IGI)

Anna Maria Weiss b. Ober Struse, Schlesien, Preussen 24 Mar 1884; bp. 6 May 1922; m.—Wolf; d. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 20 Mar 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, No. 20, 18 May 1941, p. 80; IGI)

Christiane Johanna Zwilling b. Malian, Schlesien, Preussen 6 Jun 1873; dau. of Karl Friedrich August Zwilling and Pauline Juliane Seifert; bp. 7 Jul 1909; m. Breslau, Breslau, Schlesien 24 Apr 1899, Friedrich Karl Richter; 6 children; d. cholera Breslau 29 Jun 1945 (IGI; PRF)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Werner Hoppe, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann on June 10, 2008.

[3] Ruth Gottwald Richter, interview by the author in German, Aschersleben, Germany, May 31, 2007, summarized in English by the author.

[4] Kurt W. Mach, autobiography, 1965 (unpublished); private collection.

[5] Elisabeth Nowak Mach, autobiography (unpublished); private collection.

[6] Ruth Nestripke Dansie, journal page 6–7, trans. the author, MS 9556; Church History Library.

[7] Ibid., 9.

[8] Ibid., 10–11.

[9] Ibid., 16–17.

[10] Ibid., 22–23.