Breslau South Branch, Breslau District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 121-36.

The Friedrichstrasse ran east–west through the Schweidnitzer Vorstadt area of Breslau. The Breslau South Branch rented rooms in house number 32 of that long street, and the branch territory was essentially the southern part of the city. Manfred Deus (born 1930) and his sister Katharina (born 1933) recalled that the meeting rooms were in the main floor in what had previously been office space. Heinz Koschnike (born 1930) added these details:

We had the entire main floor. There was a corridor between small classrooms and the main meeting room. From the main room, there were two more classrooms behind it. We had restrooms and a cloak room on the other side. The décor was very simple, but we had a very impressive picture of Jesus Christ at the end of the room behind the stage (raised platform).[1]

Priesthood and Relief Society were the first meetings held on Sunday mornings, followed by Sunday School at 10:00 a.m., and sacrament meeting in the evening. Primary and MIA were held on Tuesday, the former in the afternoon and the latter in the evening.[2]

The typical attendance at meetings in the early war years was about one hundred persons, according to Annelies Hendriok (born 1923). For her and the youth of the branch, church involved much more than regular worship services. “I especially liked the dances that the youth group of our branch organized. And the plays that my mother made us perform were always very nicely done.”[3]

| Breslau South Branch[4] | 1939 |

| Elders | 11 |

| Priests | 9 |

| Teachers | 7 |

| Deacons | 18 |

| Other Adult Males | 21 |

| Adult Females | 114 |

| Male Children | 18 |

| Female Children | 12 |

| Total | 210 |

According to Manfred Deus, priesthood service began in one’s early years:

Since the Aaronic Priesthood was in charge of cleaning the building and making the building ready for church services, in the wintertime I had to go there between six and seven o’clock in the morning and fire up the coal stoves; we had a big one in the chapel and separate coal stoves in two of the classrooms.

In July 1938, President Heber J. Grant visited Breslau. According to young Heinz Koschnike:

I saw a prophet of the Lord for the first time, and he made a distinct impression on me. He really liked children and took the opportunity to speak to the children. We all met in the Breslau Center Branch meeting hall. He blessed us all, and he blessed the rooms there, and attendees wondered about that specific blessing. He said that these rooms would survive as the meeting place for the Saints.

Reactions among Latter-day Saints regarding the treatment of Jews in Hitler’s Germany varied, as is evident from eyewitness statements. For example, Richard Deus (born 1903) was not a friend of the Nazi Party. He voiced concerns about the path Germany was taking under Hitler when a nationwide campaign of violence against the Jews left its mark on Breslau. On November 9, 1938, Nazi thugs looted Jewish businesses and invaded apartments as part of what came to be called the “Night of Broken Glass.” The next morning, Brother Deus went out to inspect the damage. As his son, Manfred, recalled:

He had the company car, and we drove through the city, and I saw the synagogues burning and [Jewish] businesses destroyed. . . . I remember my father saying that the Jewish people are not members of our church, but they are still the people that are favored by the Lord. He said this is the beginning of the end of the Hitler regime because Heavenly Father would not tolerate that.

Only eight years old, Heinz Koschnike also had vivid memories regarding the Night of Broken Glass:

A brother in our branch whom I shall not name was standing right behind me on November 9, 1938, during the Reichskristallnacht. I was an eyewitness to the destruction of the synagogue in Breslau and saw how the Jews were standing out in the street weeping. I was touched by that. I then saw this elder of the church, but he told me that I should be ashamed about being sympathetic to the Jews. “You are a German boy,” he said. I went home crying because I was so disappointed. My mother asked me what was wrong, and I said, “I’m not going to church with you anymore. What they teach us there is wrong.” She had a difficult time explaining to me what was what. She said that people have their personal opinions.

To actively support Jews meant risking personal safety. For example, Rudolf Nolte (born 1926) recalled that his father, Franz Nolte, was accustomed to dealing with Jewish merchants. As a police officer, he once needed a pair of boots made and decided to have the work done by a Jewish cobbler who was already in a concentration camp. Somehow he arranged to have the Jewish man issued a pass to leave the camp to see his family. The Gestapo found out, and Franz Nolte was taken to court. Convicted of illegally supporting Jews, he was sentenced to a prison term “until the end of the war and five years thereafter.” He actually served only one year of his sentence (six months in each of two concentration camps—Dachau and Auschwitz), but lost his occupation.[5]

Richard Deus met Church President Heber J. Grant (left) in Breslau in 1938. Brother Deus was the only full-time male missionary in the East German Mission when the war began. (M. Deus)

Richard Deus met Church President Heber J. Grant (left) in Breslau in 1938. Brother Deus was the only full-time male missionary in the East German Mission when the war began. (M. Deus)

Fritz Neugebauer, branch president, was born in 1892 and served in World War I. Perhaps his war experiences soured him on politics. According to his daughter, Ingeborg (born 1926):

My father was never interested in any political happenings and did not want to participate in a party. My father always tried to conduct his life in a way that the Church approved. On Sundays, he was supposed to go and work on air-raid shelters, but he usually pretended to be sick so that he could fulfill his calling as a branch president.[6]

Annelies Hendriok had dreamed of being a pediatrician. However, because her father had worked for a Jewish firm before the war, he had lost his job and was unemployed. The money Annelies needed for medical school was not there. Her mother insisted that she be trained as a hairdresser, which she did for three years.

World War II began on September 1, 1939, with the German invasion of Poland. During the first week of the conflict, one or two minor air raids occurred over Breslau, about seventy-five miles from Polish territory. Little damage was done, and there would be no more attacks on the city until 1945.

When the war began, Elisabeth Wanke (born Elisabeth Bräulich in 1919) had been a member of the Church for only two years. She had married Helmut Wanke (a priest in the Breslau South Branch) in 1938, and the branch had given them a big party, but there had been no time for a honeymoon. Helmut worked for the government, promoting sports and recreation programs in small towns near Breslau and enjoyed the use of an automobile for his work. That employment ended when he was drafted the day the war started. Fortunately, he was first stationed in Breslau and was allowed to visit his young bride quite often for the first year.[7]

The family of Richard and Gertrud Deus lived on Wielandstrasse, about twenty minutes from church on foot. Richard Deus was called in March 1939 to serve as a traveling elder and assigned to work in the Dresden District. He left his wife and four children to serve the Lord as a full-time missionary. In August, when all foreign missionaries were withdrawn from Germany, Richard was the only male missionary left. He served for two more years, part of the time in the Königsberg District and Zwickau District. He wrote the following for the Sonntagsgruss, the mission newsletter, in November 1940:

Wherever I went I was accepted by the government and the people. In the eyes of the members of the Church I saw great joy whenever we elders visited them. Often, their small apartments were rearranged to make room for an extra bed, or they would even make a whole room available for cottage meetings for us. After being fed spiritually, the members went out of their way to provide food for the body also. Many times it was a great sacrifice for them.[8]

“I was baptized exactly on my eighth birthday—October 7, 1939,” explained Hartmut Wegner (born 1931). “It was done at night, in secret if you will, in the Oder River.”[9] The family of Oskar and Hildegard Wegner lived in the suburb of Brockau. A short train ride of ten minutes brought them to the main station in Breslau, and it took another ten minutes on foot to reach the meetinghouse of the South Branch.

By 1940, Annelies Hendriok had finished her training as a hairdresser, but she still longed to work in medicine. She had made the acquaintance of a Lutheran pastor who worked in a hospital, and one day sought him out. He arranged for her to begin working there. This upset Annelies’s mother, who had gone to great lengths to find her daughter a position for training in one of the finest salons in Breslau. Nevertheless, Annalies began a two-year program in nursing in a local hospital and worked as a nurse for the duration of the war.

When he became ten years old in 1940, Manfred Deus was inducted into the Jungvolk along with his classmates. “We were kind of forced to attend the meetings, because your ration cards depended on being certified by that organization that you attended and supported the activities.”

Ingeborg Neugebauer also felt pressure from the local government in connection with the Hitler Youth program. Her father, branch president Fritz Neugebauer, did not support her attending Bund Deutscher Mädel activities. The result of this noncooperation was that Ingeborg’s final grade in the training program she completed was reduced one full grade. Other than this penalty, she did not recall any conflicts between Hitler Youth activities and the branch meetings.

“My mother was a feisty woman,” recalled Ursula Kundis (born 1937). She told the Hitler Youth people that if they marched on Sunday, her son would not march with them. On one occasion, she went to collect her husband’s military pay and greeted the officials with “Good morning!” rather than “Heil Hitler.” When chastised for not using the official greeting, she responded: “I’m sorry. The only person I will ever hail is my Father in Heaven.” A hearty “Heil Hitler!” was yelled at her as she left the office.[10]

The Hitler Youth association was not attractive to young Hartmut Wegner. “I was not boy scout material,” he later explained. Fortunately for him, his school was destroyed and he attended split sessions in another building. With classes running from 2:00 until 7:00 p.m., there was no way for him to attend the Jungvolk meetings. “I was never inducted in the first place, which made me happy.” School was not always easy for Hartmut, who recalled, “At one point we all had to declare what religion we were. Of course, everybody laughed in a very harmful sort of way when I said what I was because they associated this with American Westerns of some kind.” However, he did not recall being seriously persecuted because of his faith.

Young Heinz Koschnike had no difficulties being the only Latter-day Saint boy in his neighborhood or in the public school. He was a good student in general but also in the required religion classes. He recounted the following experience:

Across the street from the school there was a candy store. I would go there quite often, and the lady owner once said, “You know, you are different from the other children who come here. What is going on? Why do you behave differently?” I told her about my upbringing, and I told her about my faith in God. Years later, God brought us to Bischofswerda, and we were visiting a sister in a small town nearby. She invited lots of neighbors to her house for a cottage meeting. There were three older persons I baptized there. They were the owners of the candy store in Breslau.

During the war, some Latter-day Saints admired Adolf Hitler and wished to express that admiration publicly. Heinz Koschnike described an incident he witnessed in the rooms of the Breslau South Branch:

One day I came into the priesthood meeting room where we had a large, really impressive picture of Jesus Christ smiling. I saw this brother standing on a chair replacing that picture with a large picture of Adolf Hitler. He took the Christ picture down and hung up the Hitler picture. Then Brother Zelder protested and asked, “What do you think you are doing here? Take it down or I will!” Then the other brother said, “If you do that, I will have the Gestapo here in thirty minutes, and you will be on your way to a concentration camp.” Brother Zelder then climbed up on the chair and switched the pictures. Then he said, “So, Brother, do what you think is right, but don’t forget that you are a member of the Church of Jesus Christ.” The man didn’t report Brother Zelder.

“We quite often had people from the Nazi Party come in and sit and listen to what was going on [in the meetings],” according to Manfred Deus, “They were usually sitting on the back row. We knew who they were because all of the members were known.” Manfred also remembered that hymns featuring the word “Zion” were to be avoided during those instances and the Book of Mormon was quoted less often because of the notion that this was an American church.

The government instituted the rationing of food and other items of daily consumption just days before the war began. “We purchased our food with ration coupons every Saturday,” recalled Ruth Nolte (born 1915):

But we usually ran out before the week was over. We would take a potato, mash it, make it into patties, put various ingredients on it, bake it in our coal stove, and it sort of looked like cookies. I would take those to school. Sometimes mother couldn’t make her potato salad because we had no potatoes. She would grind herring, mix it with some mayonnaise, and spread it on bread. At that age, fifteen or sixteen, you were always hungry.

The Wehrmacht caught up with Elder Richard Deus in early 1941, and he was drafted. After being trained as a medic, he was sent to the Eastern Front, where the German offensive had begun in June 1941.

Under German government policy, a soldier’s wage was equal to what he was paid as a civilian before being drafted. In the case of Richard Deus, this was a serious problem. Because he had been paid nothing as a missionary for the two years before his induction, the army was not obligated to pay him anything at all. It took a substantial effort on his part to get the army to pay him for the support of his wife and four children. Eventually he was granted the minimum pay. At home, his wife was called to be the district Relief Society president. This required her to leave home on Sundays to visit other branches, and on occasion her children went to church alone.

Rudolf Nolte finished eighth grade in 1943. During the school year, his entire class of boys was trained in the operation of an antiaircraft battery near the town of Kraftborn. “We practiced loading and unloading the gun,” he recalled. While there, the boys were visited by their schoolteacher for lessons twice a week. That fall, Rudolf began a term of six months in the Reichsarbeitsdienst program.[11]

Rudolf Nolte was drafted into the army in the March 1944 at the age of seventeen and was initially trained in everything from bridge construction to mine laying. By the time he was eighteen, he was enrolled in an officers training program in the city of Rathenow, west of Berlin. While there, he attended meetings with the branch. He was a deacon at the time and carried a copy of the Pearl of Great Price.

In 1944, Richard Deus developed blood clots in his knees and could not bend his legs. He was then sent to an army hospital in Breslau, where he stayed for about four months. His family was allowed to see him there. When he had recovered enough to serve again, he was sent to Italy where the climate was milder.

Manfred Deus recalled visiting the Liegnitz Branch, about one hour to the west, to provide priesthood services in the absence of worthy brethren there. He took the train there with Carl Aeppin. In addition to assisting in the sacrament service (the only meeting held in Liegnitz at the time), Manfred played the reed organ and gave a talk each week.

In August 1944, three weeks after his fourteenth birthday, Manfred found a draft notice waiting for him. As a new Hitler Youth member, he was to report for duty at the railroad station the next day. With only one and a half days of training with a rifle, he was sent to dig trenches around the city for the defensive troops. At the time, Manfred was the secretary of the Sunday School. He recalled that one hundred or more persons attended on a typical Sunday. The percentage of attendance was calculated based on a branch population of 250.

A group of Saints met in the Nolte home at Christmastime 1943. (R. Nolte)

A group of Saints met in the Nolte home at Christmastime 1943. (R. Nolte)

Elisabeth Bräulich Wanke was the Primary president for two years during the war. Because Wednesday was traditionally a short day at school, Primary meetings were held after school on those afternoons.

As the war dragged on, conditions in Breslau grew worse, and bad news became a weekly if not a daily reality. However, the members of the Breslau South Branch continued to serve the Lord. Heinz Koschnike later recalled:

There were no interruptions in our meeting schedules right up to the end. Of course, we had mostly older people there. The testimonies we heard in those days were really spiritual. We stuck together like never before. We prayed and wept together. The Lord was with us.

Annelies Hendriok saw her family being pulled apart as the war progressed. Her mother, who was employed at a local army post, was sent to Belgium. Her father—too old to be on active military duty—was sent to the Soviet Union where he worked in materials management. Her brother was drafted into the Waffen-SS, and her sister was in the Reichsarbeitsdienst. Annelies was alone in Breslau and was saddened by the fact that “our entire family was in all kinds of different places.”

As could be expected, the war did not prevent young people from falling in love. Indeed, in some aspects, the war may have expedited the process. Annelies Hendriok recalled how several young men in the three branches of the Church in Breslau were interested in her: “They would often ask me to marry them so that they could return to the front with a little bit of hope.” However, her soldier brother very strictly warned her against making any hasty decision. The advice was good, given the high rate of death among the young men of the Breslau branches.

At her work, Ingeborg Neugebauer met a fine soldier who had lost an arm in the Soviet Union and was assigned to training programs. His name was Paul Gildner. He was not a member of the Church but attended meetings with her now and then. They were married on September 16, 1944. As she later recalled:

We were married in the civil registration office, and later we also had a celebration in our branch house. The entire branch attended. We rode in a white, horse-drawn carriage to our branch building. We even had a red carpet that they had laid down in the entrance to the branch rooms, and we had some golden chairs that we sat on.

Paul Gildner was a God-fearing man who eventually gave up his Sunday soccer games (having only one arm did not diminish his love for the sport) to attend church with his wife. Nevertheless, Ingeborg felt that some members of the Church were disappointed that the branch president’s daughter had married a non-LDS man. Her mother was more accepting, saying that Ingeborg’s husband replaced the son she had lost in the war. The newlyweds found an apartment in the same building in which her parents lived.

By the late winter of 1944–45, the meeting rooms of the Breslau South Branch at Friedrichstrasse 32 had been destroyed. The same was true of the rooms used by the Breslau West Branch. The surviving members of the three branches in the city all gathered in the rooms of the Center Branch at Sternstrasse 40. Heinz Koschnike recalled that the members, who were once surprised at the blessing pronounced on these rooms by President Heber J. Grant in 1938, now recognized that the blessings were literally fulfilled (see above).

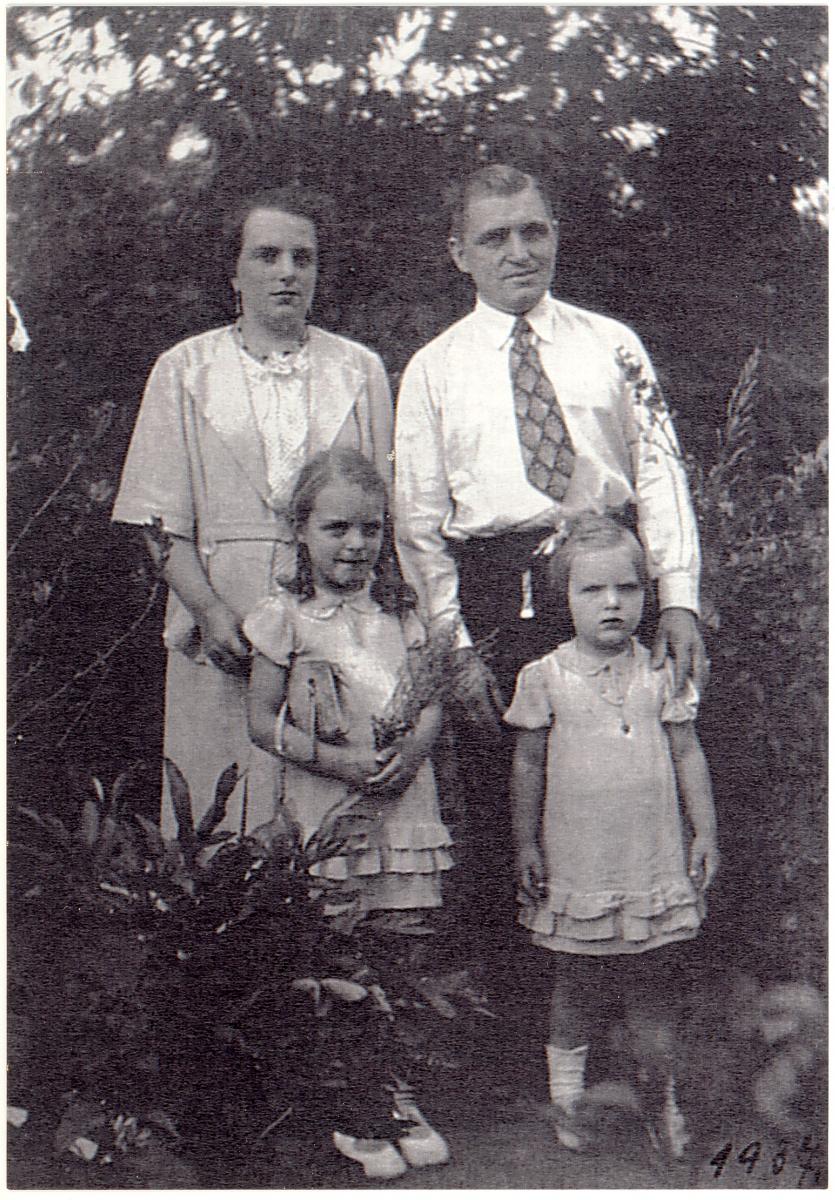

The Glaubitz family of the Breslau South Branch (S. Glaubitz Bellersen)

The Glaubitz family of the Breslau South Branch (S. Glaubitz Bellersen)

The Wanke family was together in East Prussia for Christmas 1944. Just after New Year’s Day, Elisabeth heard a voice one night saying, “You have to leave on the seventeenth!” Nobody was in the room but her husband and her daughter, who were sound asleep. The next morning she informed her husband of the message. He believed that she should stay, and they argued, but she stood her ground, insisting that she must heed the voice and return to Breslau. She left for Königsberg on January 17. The train scheduled to take her back to Breslau was cancelled because the advancing Red Army had cut off the route. Elisabeth was expecting her second child, so she sought out the station’s Red Cross service. A nurse put her on another train just before it was opened to the crowds of teeming refugees. Had she left a day later, she would have been stranded in Königsberg. She was not yet safe, however, because her train was fired upon by the Soviets, and the trip westward via Posen was anything but pleasant. She arrived home in Breslau just in time to be ordered out when the city was declared a fortress. However, her father, Albert Bräulich, was very ill and her mother, Emma, would not leave him. Elisabeth decided to stay, telling her mother: “I’m not going to leave. I’ve seen what happens on those trains. If I’m to die, I want to die at home.” They all stayed in Breslau.

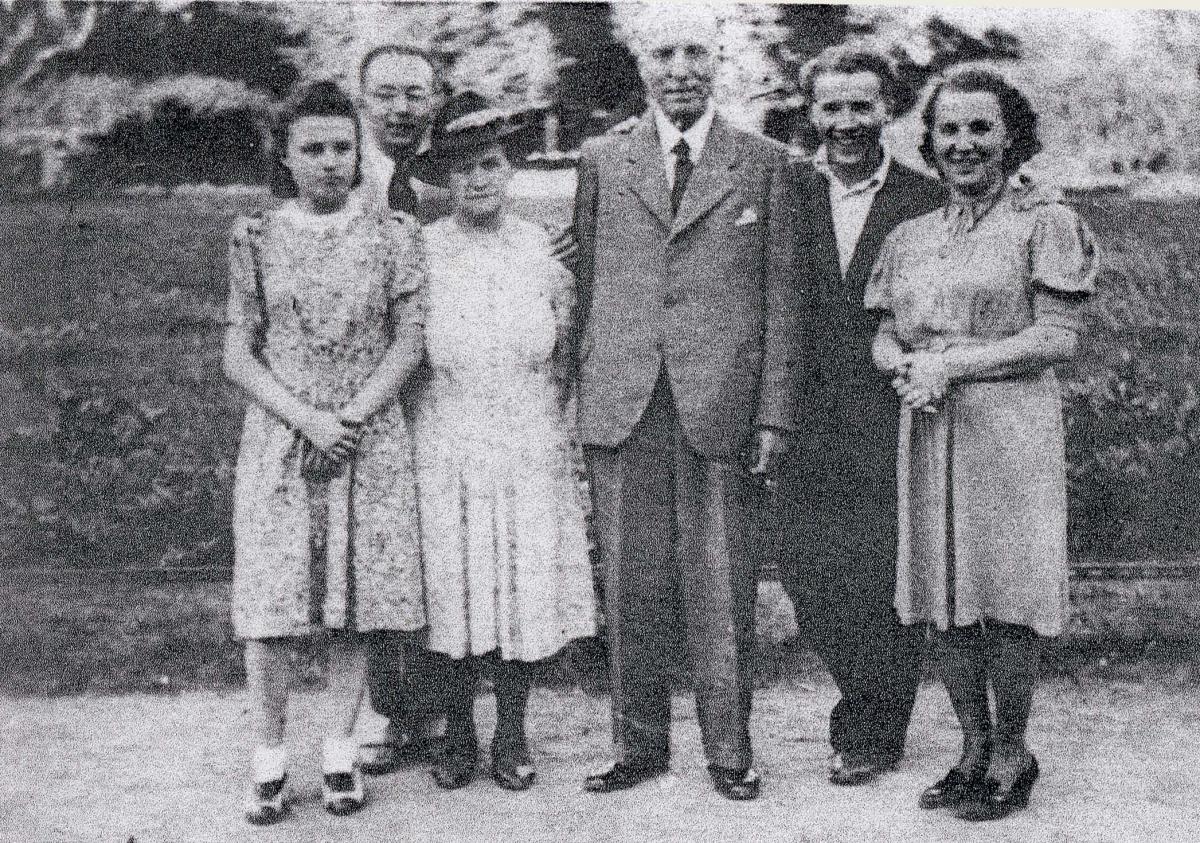

Breslau South Branch members in 1944 (R. Nolte)

Breslau South Branch members in 1944 (R. Nolte)

By 1945, the Breslau South Branch had already lost a number of its unmarried men and fathers in the war. A memorial displaying the names of the fallen was painted on the wall of the main meeting room. According to Heinz Koschnike:

To the right and the left [of the chapel door] we had the Iron Cross. Within the crosses we had the names and dates of the men in beautiful handwriting. One of the older men did the artistic work, Brother Zelder. He had only three sons. The government took his third son from the front to the interior after the first two were killed so that he would be safer, but an attack on the airfield where he was stationed killed him. But Brother Zelder never complained and never lost his testimony. He found his comfort in God, and he radiated this power in his testimony and his spirited talks.

Manfred Deus remembered counting twenty-three names on the wall by the end of the war. The Deus children left Breslau before their father’s name could be added to the branch memorial.[12]

Hartmut Wegner recalled one of the last meetings of the Breslau South Branch in January 1945. “We lined up all of the chairs (there were no pews) in the room in which we held sacrament meetings. We all knelt, each one in front of a chair, and a very heartfelt, highly emotional prayer was sent up: Should we leave or should we stay?” Later, the Wegner family held a council and decided they should leave—except, of course, for Brother Wegner, who was required to stay and defend the city.

With the Red Army approaching Breslau, the local Nazi Party district leader, Karl Hanke, declared Breslau a “fortress” that must be defended to the last man. In January 1945, he gave orders that women and children who wished to leave must do so immediately, but all men were required to stay in the city.

“We didn’t suffer at all until the Fortress [January 1945],” recalled Elisabeth Bräulich Wanke. There was still enough food, fuel, electricity, and water for the city’s residents. By then, her daughter was five years old.

On January 2, 1945, Rudolf Nolte completed a two-week furlough at his home in Breslau. Originally bound for the Eastern Front, he was detained as part of the force to defend the city against the Red Army that was fast approaching. “Our company served a one-block area of apartment houses, a distance of three streets away from where I had lived for almost seventeen years,” he later wrote. Wounded on March 2, he spent the rest of the war in a hospital. When he recovered, the conquerors shipped him east to perform reparations labor.

Paul Gildner was not allowed to leave Fortress Breslau, but he was able to send his wife, Ingeborg, to live with his parents in Langenbielau—a few miles out of town. In February, he was released from Breslau, picked up his wife at his parents’ home, and found passage on a train heading west to Dresden.

Breslau South Branch Mother’s Day photo (S. Glaubitz Bellersen)

Breslau South Branch Mother’s Day photo (S. Glaubitz Bellersen)

Heinz Koschnike was old enough in 1945 to be a member of the Hitler Youth, but he found ways to avoid involvement. When his school comrades were sent to defend Breslau against the besieging Red Army, Heinz found work that offered him an exemption:

Fritz Neugebauer had a teamster business, and he had to take supplies up to the front and the civilians. He told me to come help him so that I would not have to go to the front. I never had to use a weapon. We were on the road constantly to deliver stuff. Of course we were under fire quite often. But we were [Church] members working together. We prayed together every day, and the Lord protected us.

One day in January 1945, Heinz was on his way home when the air-raid sirens sounded. He ran into the cellar of a nearby apartment building to wait out the attack. He described what happened:

I had this strong feeling that I should leave the cellar immediately. The people there demanded that I stay because the all-clear had not yet been sounded. Despite their demands, I left the cellar immediately and hurried down the street. Suddenly I felt the air pressure from an explosion behind me and knew that something had happened. I turned around and saw that the building where I had been in the cellar had received a direct hit and had collapsed. I started to cry because God had saved my life.

By February 1945, the Red Army had fought their way to within two blocks of the Bräulich apartment, so Elisabeth and her parents were ordered by the police to move toward the center of the city. Elisabeth’s brother-in-law, branch president Fritz Neugebauer, brought his team and wagon around and moved the family’s belongings. The ride through the city center was an adventure, as Elisabeth later recalled:

You wouldn’t believe how scared those horses were when the artillery [shells] hit the big buildings! Oh, the noise! Uncle Fritz had a hard time [controlling] the horses, especially when we went over a great big bridge over the Oder River. I was afraid they would go over the railing and jump down [into the river]. . . . I was pregnant at the time. My little girl and I were sitting next to Uncle Fritz up front. . . . It was a flatbed trailer. Mother and a friend [were in the back and] held on to the luggage.

The Bräulich family was assigned a nice apartment where they stayed until several months after the war. Since leaving her husband on January 17, Elisabeth had no idea where he was. In March, her daughter was born. Elisabeth walked forty-five minutes to the hospital, where she was given a bed in the basement. The nurse gave her a shot to expedite her labor, but used the wrong drug. Her labor lasted ten hours.

Ursula Kundis was only eight years old when the bombings of Breslau became frequent. She remembered her mother making “air-raid cookies” that she always kept ready to take to the basement when the alarms went off. As Ursula later recalled, “The neighbors would say, ‘Mrs. Kundis, would you pray with us? You know how to do it.’ And so we would pray together.” On one occasion, they were surprised when residents of the adjacent house—some of whom were injured when the house collapsed—escaped through a hole in the wall into the basement where the Kundis family sat.[13]

Anna Frieda Sowada responded to the call to evacuate Breslau in early February 1945. She put her daughter, Mary (born 1939) on a sled, wrapped her up in a blanket, and said good-bye to her husband (“I’ll catch up with you,” he replied). Breslau women were told that they would be returning to the city as soon as the invaders were driven back. As it happened, they did not return, but were put on a train heading west, ending up in a small town in Bavaria (southeastern Germany).[14]

Gertrud Deus believed that she needed to stay in Breslau in order to assist single sisters in the city’s three Latter-day Saint branches, but she was then persuaded that her own family’s safety was perhaps more important. Moments after packing up to leave Breslau and locking the door to their apartment, Gertrud Deus turned around and went back. “What are you doing, Mom?” her children asked. “I forgot my genealogical papers!” was the reply. Manfred recalled that it was twelve degrees below zero when they loaded their belongings onto a sled for the trip to the railroad station. The train headed slowly west, with no specific destination. Along the way, their only source of water was snow gathered by passengers when the train stopped. Stops were frequent, and the journey to Görlitz that would normally have lasted about three hours ended up taking three days.[15]

In Görlitz, the Deus family got off of the train and stayed with friends. They had been told that they would be returning to Breslau after the Red Army was driven back, but such optimism was unfounded. After two weeks in Görlitz, they headed farther west to the city of Dresden, arriving there on February 11. Two days later, the worst air raid in Europe during World War II took place there. Tens of thousands perished in the firebombing of that industrially insignificant city crowded with refugees. Fortunately, Gertrud Deus had found a place to live with friends on the outskirts of Dresden. They were not harmed, but the air pressure from the exploding bombs broke the windows of the home in which they were staying.[16]

Oskar Wegner sent his family west on his wife’s birthday—January 22, 1945. Fortunately, he was able to follow them just a week later, having been classified physically unfit for military duty. He caught up with them in Wallenberg, just a few miles south of Breslau. From there they proceeded by truck and train to Bavaria in southeastern Germany.

The Breslau South Branch choir (M. Sowada)

The Breslau South Branch choir (M. Sowada)

Ruth Nolte and her mother had been evacuated from Breslau and arrived in the Dresden main station at precisely the wrong time—just hours before the firebombing on February 13 and 14. They accidentally met Ruth’s sister, Ilse, and her sister-in-law, Iffa, in the station and all sought refuge in the basement shelter. After the first attack (at 10:00 p.m. on February 13), they left the shelter and crossed the river into Dresden Neustadt. There they listened to another attack two hours later. The next day, they walked through the devastated city to the main station to locate their luggage, but it had all burned. With only the clothes on their backs, they found a train to take them west to Chemnitz and south to Annaberg-Buchholz.

Ingeborg Neugebauer Gildner was yet another member of the Breslau South Branch who experienced the firebombing of Dresden firsthand. She later vividly recalled what she saw that terrible night:

During the attack on Dresden, we saw animals [from the zoo] running around [town] and people in the streetcar had died because of the air pressure of the bombs. They looked like they were only sleeping. Fires burned in the city but not where we were. There were planes shooting at the people trying to flee. It was horrible. Everything was in chaos.

Richard Sowada (born 1905) was not as fortunate. He too had arrived in Dresden just a day or two before the firebombing, having left Breslau with his sister and his mother. Later, members of the Deus family reported seeing Brother Sowada in Dresden at the home of some Church members. When the air-raid alarm was sounded, the Deus family and the Sowadas went to different shelters, and Richard Sowada was never seen again. It was eventually assumed that he perished in the attack; he was declared legally dead as of February 14, 1945.

Richard Sowada was the popular choir director in the Breslau South Branch. (M. Sowada)

Richard Sowada was the popular choir director in the Breslau South Branch. (M. Sowada)

The Soviet siege of Breslau was characterized by an incessant artillery barrage. When it was too dangerous to be in the streets, members of the South Branch held worship services in their apartments. According to Heinz Koschnike, “the word was circulated each week that meetings would be held the next Sunday in the apartment of Brother or Sister so-and-so.”

The last church meetings in Fortress Breslau that Elisabeth Bräulich Wanke could recall were held in the apartments of member families. According to her:

Every Sunday afternoon, even when the bombs were falling all the time, it was quiet and we could have sacrament meeting. And we had one deacon, and he would pass the sacrament. And Uncle Fritz [Neugebauer] was a very positive and very faithful member. And he would always give us encouragement that the Lord will protect us there, you know [from] the shooting or the bombing. Uncle Fritz would interrupt the speaker and we would sing a song really loud so we couldn’t hear [the artillery]: “Master, the Tempest Is Raging” or “Jesus, Lover of My Soul.”

With the capitulation of Fortress Breslau on May 6, 1945, the conquerors entered the city to find that they had been held at bay for eleven weeks by old men (the Volkssturm) and Hitler Youth. Heinz Koschnike remembered the declaration by his mother, Clara Maria, at the time: “The power of the priesthood kept them out. Normally, it would have been a simple thing for them to storm the city against such weak resistance.”

Latter-day Saint women in Breslau were as attractive to Soviet soldiers as any other German women. Thus it was only a matter of time before Sister Koschnike found herself in serious danger. In the words of her son Heinz:

A drunken soldier came into our house and wanted to get my mother. As a young boy [age fourteen] watching this, I could not just stand there and let it happen. I ran outside and pled to the officer in the street (he was watching out over the entire campaign). His heart was softened, and he came into our house and ordered the drunken soldier out of the room. That is how my mother was saved from this shameful fate.

In their Bavarian village, the Wegners experienced the entry of French troops on April 20, 1945. They were relieved when nobody made any serious attempt to stop the invaders. For them, the war was over. Over the next few months, they made a trek through various parts of the country, ending up in Herne in northwestern Germany. According to Hartmut, “My father’s first concern was always to establish contact with the Church wherever we were. . . . This was our lifeline. If we could find a branch, we would have a connection with somebody.” The Latter-day Saint branch in Herne was probably pleased to welcome the Wegner family.

When the war ended, Mary Sowada and her mother were living with two Catholic nuns in a small Bavarian town. Over the next few months, they were housed in filthy barracks with hundreds of refugees and countless rats and were then sent to northern Germany. They began a new era of life in Braunschweig in the British Occupation Zone.

In the ruins of Dresden, Gertrud Deus was invited by Church members to move into an empty apartment. When the Soviets entered the city in May, the locals thought the invaders were Americans and came out to greet them. When they learned the true identity of the soldiers, the women all ran for safety. Sister Deus did her best to hide her sixteen-year-old daughter, Gisela. On one occasion, a Russian soldier saw Gisela go into the house and tried to find her. He could not find his prey but came back several times to look for her. According to Katharina, “he would just stand there [in the street] and stare at the house because he could swear that he saw [my sister] go in there.”

Richard Deus had spent very little time with his wife and his four children after being called as a missionary in March 1939 and as a soldier in 1941. On April 23, 1945, just two weeks before the end of the war, he was killed in action against the American army in northern Italy. His wife and children had essentially lived without him for more than six years.

When the war ended, Ruth Nolte and her mother were in Annaberg-Buchholz in Saxony (south of Chemnitz). Because they had relatives in the city of Hanover, they were allowed to travel to that city in the British occupation zone. The trip took two months. “The hardest thing about the war was that so many people died,” Ruth later recalled. “You didn’t think much about dying or being killed, but when it was over, you surely were glad to be alive!”

Richard Deus was killed in Italy two weeks before the war ended (M. Deus)

Richard Deus was killed in Italy two weeks before the war ended (M. Deus)

Just before the war ended, Paul Gildner was assigned to a training facility in Salzburg, Austria, and was able to take his wife, Ingeborg, along. He found her in Dresden shortly after the firebombing of February 13 and 14, and they took the long train ride south through Czechoslovakia to Salzburg. It was there that their first child was born a few months later. Then the Gildners located the LDS branch in Salzburg and joined with seven members of that branch to hold meetings. Paul Gildner was baptized a member of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in June 1945—one of the first postwar converts in Germany.

Several months after Germany surrendered, the Allied occupation officials in Austria began to send refugees back to their own homes. Ingeborg and Paul Gildner faced the frightening thought of returning to Breslau, already in Polish hands, and looked for a way west. Fortunately, one of the American soldiers serving in Salzburg was a former missionary in Germany, and he produced the papers the Gildners needed to escape to the west—into the American occupation zone.

Hartmut Wegner’s family did not return to Breslau. Their home had been destroyed, and they had lost all of their property, but more importantly (according to Hartmut years later), “we lost our identity, because our ancestors . . . had been there from the seventeenth century.”

The Breslau apartment house in which the Kundis family lived was eventually bombed out. As Ursula recalled, “We had a piano, it was the only piano in the building. [Mother] could see some [piano] keys in the rubble, and that was it for the house.” Sister Kundis was expelled from Breslau with her family in December 1945 and, after living in refugee camps, was finally reunited with her husband in Bremen, West Germany, in 1946.

On July 2, 1946, Elisabeth Bräulich Wanke was compelled to leave Breslau with her children and her parents. Still uninformed of her husband’s whereabouts, she was eventually given a place to live in distant East Frisia, not far from the Netherlands in northwestern Germany.

In June 1946, Rudy Siebenhaar (born 1929), a native of Breslau, was able to escape from a Soviet prison camp and make his way carefully back to Breslau. On a Saturday afternoon he went to a black market gathering, where he watched two German girls trying to trade porcelain items for food. When their attempts to communicate with the Poles broke down, Rudy intervened and helped them get more for their valuables. He asked if they could meet there the next day, but they said that they would be attending church. “What kind of church?” he inquired. “We are Mormons,” was the response.[17]

Rudy recognized the name of the Church from an encounter with another POW a few months earlier. He had heard the story of the Prophet Joseph Smith and agreed to join the girls for church meetings the next day. The surviving Saints in Breslau all met in one group, in a deaf-mute school building right around the corner from Rudy’s apartment. He was converted and baptized on August 13, 1946.

Branch president Fritz Neugebauer was eventually transported to Holthusen in East Frisia (northwest Germany) and went from there to Wilhelmshaven, where he established contact with the Church again. His wife also escaped to the west to be reunited with her husband, but his mother died in a refugee camp along the way in Czechoslovakia.

About one year after Rudolf Nolte was sent to the Soviet Union, camp guards found and destroyed his copy of the Pearl of Great Price. “I had a testimony,” he later wrote, “but I had no religious affiliation or training for years.” All he ever thought about in those days was when he would be allowed to go home.

Since December 1941, the East German Mission had no contact with Church leadership in Salt Lake City. In the months immediately following the war, branch president Langner in Breslau wrote many letters to Salt Lake City to ask for guidance. Apostle Ezra Taft Benson arrived in Breslau in the fall of 1946 as part of his mission to ascertain the status of the Church members in Europe and to distribute welfare supplies. Heinz Koschnike was there and remembered the gathering well:

One day in 1946 [Elder] Benson came to our apartment with two American officers, all Mormons. He talked to us in a special meeting. I met President Benson in person. He told us that the gospel had to be preached in Poland as well. We stared at each other. We then told him that we wanted to live among Germans, move to Germany. We didn’t want to stay in Poland. He said that he would inquire of the Lord and that we would meet again tomorrow. The next day he said that he had an answer from the Lord. We were to leave, and he would go to Warsaw to arrange it all. We would go to Frankfurt am Main. We didn’t want to go to the Russian Zone in Germany. Which other zone was not important.

Shortly thereafter, the evacuation of the surviving Saints from Breslau began. They included “about one hundred people, mostly women and children, and about twenty men” according to Rudy Siebenhaar. They were shipped in cattle cars to the west. Heinz Koschnike put the number at closer to two hundred persons. The company was delayed at the Polish-German border for at least a week, during which the following happened, according to Heinz:

At the border, we would go up the hill from where the train was standing and have our meals. We called it Mormon Hill, and we had a church service each evening. And Polish people came from the town nearby to join us. More and more of them came, they loved the music, etc.

The plan to take the Saints to Frankfurt in the American occupation zone was thwarted when the Soviet officials refused to allow the Saints to pass through their occupation zone. The refugees were split into two groups and sent to the neighboring towns of Rammenau and Bischofswerda in the province of Saxony in the Soviet occupation zone. The refugees quickly found the Saints in Bischofswerda and went to church the next Sunday:

On Sunday we went to church. That was in a Hinterhaus and there was a winding staircase. Those older sisters who had prayed for us [that priesthood holders would come] were so thrilled to have their prayers answered and they greeted us with tears. There were too many of us to even fit in the rooms. There were about one hundred of us. That was in September 1946.

As a prisoner of war in the Soviet Union, Rudolf Nolte endured terrible conditions. Often given only bread and watery soup amounting to no more than five hundred calories a day, he was almost always assigned hard physical labor lasting twelve hours. As he later recalled, he once tried to steal some sugar:

I noticed an empty sugar sack and proceeded to scoop a little bit of sugar into my can. I was caught and thrown in the prison for five days without food or bedding. It was in the month of March, and we had worked all day in rainy-snowy weather. So I had to cover myself with a wet overcoat. The bunk had only three planks, too small to support me. There I lay, freezing and hungry and isolated from the world. I could have died of pneumonia, and no one would have known or cared. Finally, on the last day of my confinement, I was served a bowl of watery soup. It tasted so good!

When it came time to be released, Rudolf Nolte told his Soviet captors that he was from Hanover. By that time, Breslau, Germany, had become Wroclaw, Poland, and he was afraid that his captors would detain him even longer. He was finally reunited with his family in Hanover in 1948. His father, Franz Nolte, had been drafted late in the war and was reportedly buried in a mass grave at a prison camp near Moscow, Russia.

In 1954, Elisabeth Bräulich Wanke received word that her husband, Helmut Wanke, had been officially declared dead. By that time, she had probably been a widow for nine years.

With the exodus of fall 1946, the Breslau South Branch disappeared into history.

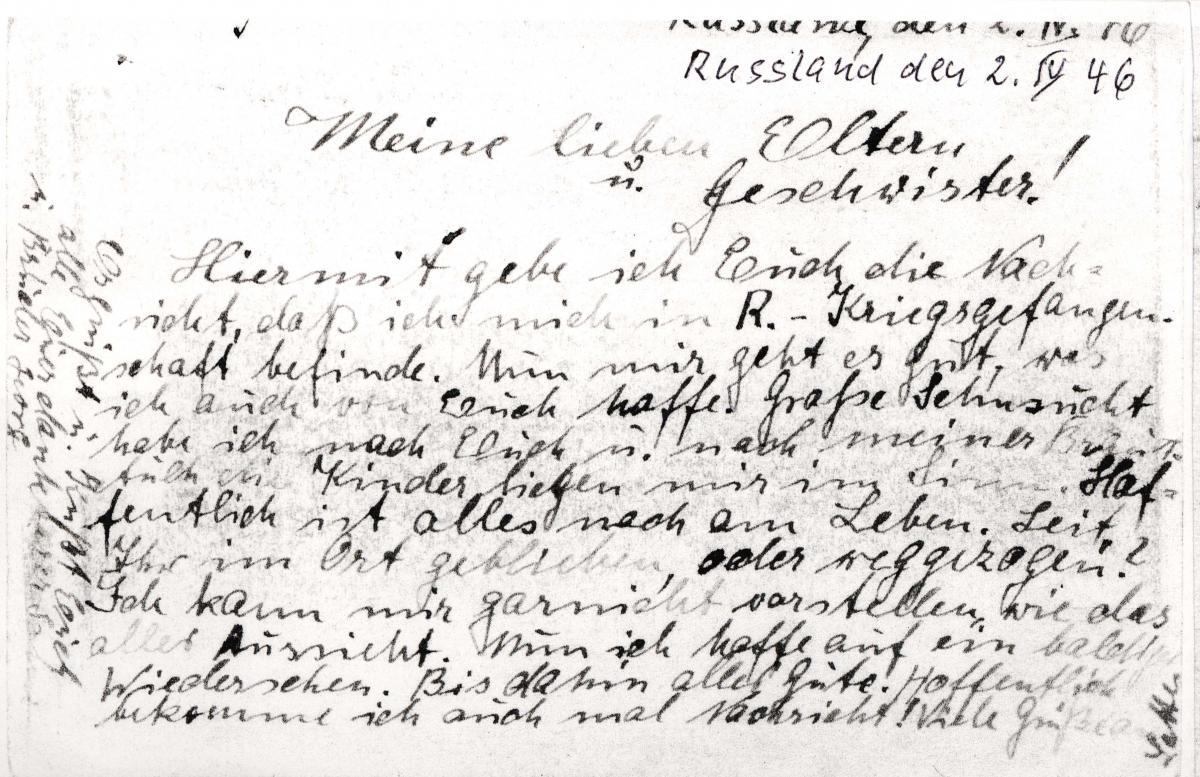

Georg Janitschke wrote this card to his parents in 1946 from a POW camp in Russia. His greatest desire was to be reunited with his family. He died in a POW camp in 1947. (S. Glaubitz Bellersen)

Georg Janitschke wrote this card to his parents in 1946 from a POW camp in Russia. His greatest desire was to be reunited with his family. He died in a POW camp in 1947. (S. Glaubitz Bellersen)

In Memoriam

The following members of the Breslau South Branch did not survive World War II:

Rudolf Erwin Baron b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 8 Aug 1917; son of Alfred Fritz Baron and Metaclara Caecilie Antoine Kosalek; bp. Mar 1934; m. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 20 Jun 1942, Erika Margareth Heine; non-commissioned officer; d. at San. Kp. 409 8 Apr 1945; bur. Baltijsk, Russia (IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Martha Anna Maria Bruma b. 1 Mar 1872 Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen; dau. of Johann August Anton Bruma and Christiane Schmidt; bp. 6 May 1922; m. Breslau 29 Sep 1892, Johann Franz Wanke; 10 children; d. Hohenelbe, Czechoslovakia 27 Apr 1945 (Neugebauer-Gildner; Bräulich-Wanke-Terry; IGI)

Richard Fritz Deus b. 10 Feb 1903 Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen; son of Karl August Ernst Deus and Auguste Johanna Rosalie Mintschke; bp. 3 Aug 1918 Breslau; ord. elder; m. 24 Dec 1926 Breslau, Gertrud Anna Pfeiffer; 4 children; traveling elder in East German Mission 1939–1941; non-commissioned officer; k. in battle San Benedeto, Italy 23 Apr 1945; bur. Futa Pass, Italy (M. Deus; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Georg Albert Franke b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 8 Apr 1906; son of Helene Franke; ord. teacher; d. 8 Jan 1940, Breslau; bur. Breslau 10 Jan 1940. (Sonntagsgruss, No. 41, 10 Nov 1940 n.p.; IGI)

Bruno Augustin Glaubitz b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 3 Sep 1904; son of Augustin Petrus Glaubitz and Klara Korpus; m. Breslau 30 Mar 1929, Margaretha Frieda Janitschke; 3 children; d. Stalingrad, Russia 1 Jan 1943 (IGI)

Georg Karl Janitschke b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 10 Feb 1915; son of Augustin Janitschke and Johanna Torke; bp. 2 Feb 1924; staff corporal; d. as POW Novosibirsk, Russia 20 Jul 1947 (Glaubitz-Bellersen; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Alfred Wilhelm Koska b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 11 Feb 1918; son of August Koska and Anna Rosina Walde; bp. 21 Feb 1926; d. 30 Jun 1944 (IGI)

Wilhelm Max Koska b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 22 Mar 1916; son of August Koska and Anna Rosina Walde; bp. 6 Dec 1924; m. 27 Oct 1939; lance corporal; d. Krasnyj field hospital 625, Russia 9 Aug 1941; bur. Krasnyj, s.w. Smolenzk, Russia (Sonntagsgruss, No. 2, 18 Jan 1942, p. 8; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Werner Lothar Neugebauer b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 11 Mar 1924; son of Fritz Hermann Neugebauer and Hedwig Maria Martha Wanke; bp. Breslau 3 Sep 1932; corporal; k. in battle Osscha, Smolensk, Russia 26 Oct 1943; bur. Orscha, Belarus (Neugebauer-Gildner; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Franz Nolte b. Bernterode, Sachsen, Preussen 23 Mar 1885; son of Heinrich Nolte and Elisabeth Schneider; bp. 11 Dec 1920; m. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 13 Nov 1913, Margaretha Elisabetha Leibner; 4 children; 2m. Anna Katharina Ibold; corporal; d. Soviet POW camp 6 or 11 May 1945 (R. Nolte; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Paul Schmikale b. Nangesinawe, Wangersiuawa, Preussen 30 Aug 1880; son of August Schmikale and Luise Elisabeth Mueller; bp. 24 Sep 1928; ord. elder; m. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 20 Aug 1904, Emillie Anna M. Siegmund; 2 children; d. Breslau 10 Jan 1940 (Sonntagsstern, No. 26, 28 Jul 1940 n.p.; IGI)

Georg Janitschke (S. Glaubitz Bellersen)

Georg Janitschke (S. Glaubitz Bellersen)

Richard Karl Arthur Sowada b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 23 Feb 1905; son of Karl Josef Sowada and Maria Theresia Hedwig Breuer; bp. 20 Oct 1940; m. Breslau 29 Dec 1937, Anna Frieda Bollach; 1 child; k. in air raid Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 13–14 Feb 1945 (Sowada; IGI)

Gustav Gerhard Heinrich Walter b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 25 Jul 1917; son of Gustav Hermann Walter and Elisabeth Martha Goebler; k. in battle (IGI)

Helmut Paul Johann Wanke b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 19 Oct 1911; son of Johann Franz Wanke and Martha Anna Maria Bruma; bp. 6 May 1922; ord. priest; m. Breslau 28 Oct 1938, Elisabeth Maria Bräulich; 2 children; MIA Bischofsburg, Klackendorf, Mensguth, Seeburg, Wartenburg 1 Jan 1945; ruled dead 31 Dec 1945 (Bräulich Wanke Terry; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Arthur M. Weiss b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 14 Jul or 20 Aug 1914; son of Bertha Christiane Oriwall; ord. deacon; lance corporal; d. Lipowik Russia 10 May 1942 (Bräulich Wanke Terry; IGI, www.volksbund.de)

Erwin Josef Zelder b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 26 Nov 1924; son of George Arthur Kurt Zelder and Pauline Auguste Fruehauf; bp. 27 May 1933; d. Breslau 22 May 1944 (IGI)

Herbert Georg Kurt Zelder b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 15 Sep 1914; son of George Arthur Kurt Zelder and Pauline Auguste Fruehauf; bp. 2 Oct 1922; m. Oels, Schlesien, Preussen 16 Sep 1939, Erika Auguste Emma Heinrici; d. Jul 1944 (IGI)

Paul Gerhard Zelder b. Breslau, Schlesien, Preussen 2 Dec 1922; son of George Arthur Kurt Zelder and Pauline Auguste Fruehauf; bp. 26 Feb 1931; noncommissioned officer; d. 20 Sep 1944; bur. Allensteig, Austria (IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Notes

[1] Heinz Koschnike, interview by the author in German, Bischofswerda, Germany, June 7, 2007; summarized in English by the author.

[2] Manfred Deus and Katharina Deus Siebenhaar, interview by the author, Sandy, Utah, March 9, 2006.

[3] Annelies Hendriok Szeszeran, telephone interview with Judith Sartowski, April 9, 2008; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[5] Rudolf Nolte and Ruth Nolte, interview by the author, Sandy, Utah, November 21, 2006.

[6] Ingeborg Neugebauer Gildner, interview by the author in German, Munich, Germany, August 9, 2006.

[7] Elisabeth Bräulich Wanke Terry, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, November 17, 2006.

[8] Richard Deus, “As a Traveling Elder—On the Road,” Sonntagsgruss, no. 43, November 24, 1940; trans. Manfred Deus.

[9] Hartmut (Hart) Wegner, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann, April 9, 2008.

[10] Ursula Kundis De Haan, interview by Rachel Gale, Salt Lake City, June 29, 2007.

[11] Rudolf Nolte, “My Life Story,” 2004 (unpublished personal history); private collection.

[12] The number of fatalities in this account does not match the number of soldiers shown at the end of this chapter. It may be that names of soldiers of all three Breslau branches were included in the memorial.

[13] See the description of such escape holes in the introduction.

[14] Mary Sowada, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, November 17, 2006.

[15] Because Hitler Youth (boys ages 14–17) were required to stay in Breslau, Manfred wore civilian clothing.

[16] See the Dresden Altstadt chapter for details on the firebombing of that city.

[17] Rudy Siebenhaar, interview by the author, Sandy, Utah, March 9, 2006.