Berlin Spandau Branch, Berlin District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 103-12.

The modern Berlin suburb called Spandau was an independent community until it was incorporated into metropolitan Berlin in 1920. Located at the far northwest corner of the Reich capital, it was home to a branch of the LDS Church that met in rooms rented at Neue Bergstr. 3 in the first Hinterhaus—a venue the Saints enjoyed long before, during, and after World War II.

| Spandau Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 4 |

| Priests | 2 |

| Teachers | 5 |

| Deacons | 3 |

| Other Adult Males | 15 |

| Adult Females | 53 |

| Male Children | 4 |

| Female Children | 0 |

| Total | 86 |

Born in 1925 to parents who had joined the Church just the year before, Rudi Seehagen recalled the layout of the rooms:

It used to be Hülsebeck’s Building Company. My first wife’s parents or grandparents were related to the Hülsebeck family; that’s why we were able to rent the rooms there. There were stalls for horses and storage space for equipment and materials; the offices were above that. The company was no longer in business, so we renovated the rooms. You went through the front building’s foyer then through a double gate then to the left and up the stairs. There were two rooms, and we removed the middle wall; that was our main meeting room. To the left was a smaller room for Relief Society or priesthood meetings. Then upstairs there were two classrooms (a total of four rooms).[2]

Rudi recalled seeing about thirty to forty people in church on a typical Sunday. Sunday School began at 10:00 a.m., with sacrament meeting at 5:00 or 6:00 in the evening.

Wolfram Dittrich (born 1928) recalled details of the seating in the chapel: “The large room had about seven rows of chairs with about ten chairs in each row. The branch presidency was seated on the rostrum.”[3]

Walter Kuefner (born 1933) recalled going to church early on Sunday in the winter season in order to heat the rooms. Traveling to church from the town of Staaken to the west (an hour’s trip), it made for a very early start to his Sunday.[4]

The Spandau Branch meetings continued with only one interruption throughout the war. An unidentified inactive member told her husband, an army officer, about their rooms in the Neue Bergstrasse. He decided to requisition the rooms for storage. Horst Schwermer and district president Fritz Fischer went to the army office and explained their need for the rooms and suggested other places the army could store their equipment. The use of the rooms for Church meetings was restored with only one Sunday lost.

The mothers of the Spandau Branch in about 1940. (R. Seehagen)

The mothers of the Spandau Branch in about 1940. (R. Seehagen)

One of the rare changes in Church practice in Germany during war was the exclusion of songs that included words such as Zion and Jehovah. “That was too Jewish,” recalled Rudi Seehagen. “Sometimes we forgot and remembered only when the word came up in the song. Well, it didn’t cause any problem. At least not in our branch.”

A variation of the ward teaching program was practiced in the Spandau Branch during the war. Rudi Seehagen was assigned to accompany Willi Knoll in visiting a total of thirteen families who lived over a wide area. Rudi remembered how they rode their bikes to communities as far away as Kladow (six miles to the south) and Niederneuendorf (four miles to the north). They were not able to visit all of the families every month.

Helga Abel was born in Spandau to Latter-day Saint parents in 1922. At the age of ten, she was inducted into the Jungvolk, the first phase of the Hitler Youth program (as was done all over Germany through the schools). It was a good experience, as she recalled:

I was singing and doing fun things, so they asked me to join the Jungvolk, and it wasn’t long before I was in charge of my group. And we had outings, and we would sing (I loved to sing), and we would go camping. At that time we didn’t have Primary, but we had the Jungvolk.[5]

When she turned fourteen and was invited to join the League of German Maidens (BDM), her mother put her foot down and denied Helga permission; it would interfere with Church meetings. During a neighborhood Nazi Party meeting in about 1936, Helga’s name was brought up as one who should be blacklisted because of her refusal to join the BDM. Fortunately for her, a non-LDS man, a Mr. Singer, whose wife was a member of the Church, stood up for her and instructed the other Party members to leave Helga Abel alone. “He saved my neck,” she claimed.

Born in 1915 in Königsberg, East Prussia, Horst Schwermer had already served as a communications specialist in a German army cavalry unit for two years and had moved to Berlin. In the spring of 1938, he went to the city center of Berlin to attend a Latter-day Saint district conference. On the way, he noticed a very pretty young lady in the streetcar. She turned out to be Helga Abel, the girl selected to officially welcome mission president Alfred C. Rees and his wife to the conference and to present them with flowers. “That’s how I found out that she was Helga Abel of the Spandau Branch,” Horst explained.[6] At the time, Helga was only sixteen years old. Horst was an employee of the Lufthansa Airline Company of Berlin.

When she was seventeen, Helga Abel completed her schooling. She had wanted to study pedagogy and become a teacher, but the war had begun and some personal choices were no longer possible. She went to work instead as an assistant to an oral surgeon and stayed in his employ for several years. Toward the end of her tenure—August 30, 1941—she and Horst Schwermer were married. As Horst recalled:

The church wedding took place in our church; Brother [Fritz] Fischer, our district president, was officiating. I picked Helga up from her parents’ apartment in a white wedding carriage drawn by two white horses. After the wedding [at the city hall], we went to Lesky’s photographer to have a picture taken.

Helga Abel and Horst Schwermer were married in the Spandau city hall. Note the portrait of Adolf Hitler in the background. (H. Schwermer)

Helga Abel and Horst Schwermer were married in the Spandau city hall. Note the portrait of Adolf Hitler in the background. (H. Schwermer)

There was no honeymoon for the Schwermers, but soon after the wedding Horst was accepted as a student at a technical college in Berlin and was able to stay at home until he was reactivated in the armed services in 1943. Until then, he served as a counselor to branch president Willy Knoll. The Schwermers’ first son was born in a Berlin hospital. As Helga later recalled:

The doctor was very unhappy with women that had babies because he had seen in Hamburg where people were on the street delivering babies and nobody could take care of them. Then part of the hospital got bombed and burned out. [My baby] was eleven days old when I left Berlin.

As the air raids over Berlin increased in frequency and severity, the city government urged mothers to take their children out of town. Helga Schwermer took the train east with her infant son, Jürgen, and found a place to live near the port city of Stettin. Before leaving home, she had offered to allow another Latter-day Saint family to live in their apartment.[7] Arriving in Stettin, she had to walk for ninety minutes to her new home—one small room in the home of some very nice farm people. “When I look back, I don’t know how we [she and Jürgen] did it. He was only eleven days old, and I walked an hour and a half.”

Helga and Horst Schwermer with their son Jürgen. (H. Schwermer)

Helga and Horst Schwermer with their son Jürgen. (H. Schwermer)

Despite wartime conditions, there were ways for children to entertain themselves. Walter Kuefner was one of many who collected shrapnel fragments after air raids. As he later explained, “We gathered them for how big they were and how new they were. If they were already a little bit rusty, they weren’t from last night. If they were shiny, [they were new].”

Wolfram Dittrich recalled the event that caused his family to move from the Berlin neighborhood of Schöneberg to Spandau in 1942:

I will never forget what happened in the night that our home was bombed. . . . Many houses stood in a row, and in the back we had a yard. Behind our home was a high school in which a bomb fell that night. We sat in our basement, and my brother was so scared because of the air pressure and the noise that he wanted to run away. I grabbed him in the last second. My mother owned a laundry in our building, and behind her working area was our apartment. The walls stood askew, and we could not live in it anymore. For this reason, we had to leave Schöneberg. The furniture was intact, but the walls threatened to collapse.

During the war, it was still important for young people like Wolfram Dittrich to progress in school. As the attacks on Berlin and its suburbs increased, schools were damaged or destroyed. School populations doubled up or held split sessions in some neighborhoods. As he later explained:

The most difficult thing for us was that the schools were also attacked after 1942. When some schools were already severely damaged and could not be used anymore, we had school either in the mornings and some classes in the afternoon because that was the only time that was available.

Rudi Seehagen was too young to serve in the military until the last year of the war, so he continued to attend church with his family in the Spandau Branch. After completing his formal training at the age of fourteen, he began an apprenticeship as a porcelain painter in the Royal Prussian Porcelain Works in Berlin. This proved to be fortuitous because it later kept him out of the Reichsarbeitsdienst (RAD) for perhaps a year. “We were completing a special commission of porcelain for Adolf Hitler, and I was granted a one-year reprieve,” he explained.

The Seehagen family about 1941. Rudi is behind his parents. (R. Seehagen)

The Seehagen family about 1941. Rudi is behind his parents. (R. Seehagen)

Spandau was a prime target for attacks by the American and British air forces. Huge factories there produced electronic equipment and tanks. During the air raids over Spandau, minor damage was done near the Seehagen home, but Rudi did not recall that any branch members lost their homes. Some of the windows in the meetinghouse burst from the air pressure of bombs exploding close by, but the building remained fully usable throughout the war.

Erich Gellersen, a member of the Stade Branch near Hamburg in the West German Mission, joined the Spandau Branch early in the war. As an aeronautical engineer, he had been transferred to Spandau by his employer, the BMW Company. Following every air raid, he rode his motorcycle around town, trying to locate members and learn how they had fared during the attack.

Out in the Pomeranian countryside northeast of Berlin, Helga Schwermer could see the lights of the fires after Allied air raids over the major Baltic port city of Stettin. On one occasion she murmured to herself, “They [the Nazis] want to build a victory on these ruins!” Next door was the family of a high-ranking officer, whose wife apparently heard Helga make what was considered to be a defeatist statement. She told her husband and the situation soon became critical. Helga recounted:

I don’t know if it was the next day or two days later, I got called to [report to] the high Nazi party official. And he gave me hell . . . “Do you know that I should send you to a concentration camp?” And I said, “But I have a baby,” and I don’t remember what he answered to that, but I was just shaking. And then I was standing in the doorway, holding Jürgen, and he said, “You can think that [defeatist idea], but don’t you ever say that out loud again.” So if he had been a convinced Nazi, I would have been in a concentration camp.

Because they lived too far from a concrete air-raid bunker, Fritz Kuefner dug a hole in the yard by the family home in Staaken. He put some logs across it and piled sand on top. According to his son, Walter, “It was more of the real thing; you could see what was happening up there. You could see the airplanes and the explosions. You could sometimes see a plane being hit and the people jumping out with their parachutes.” Being that close to the action, however, could be scary. Walter recalled worrying that the Americans who parachuted from the planes would be hiding along the way to school the next day. “The minute they came down, they were captured, but we kids didn’t know that [at the time].”

Horst Schwermer was reactivated by the military in 1943. Sent directly to the Balkans, he served as a communications officer in a motorized infantry unit. “My vehicle was always right behind the lead one. They called us the ‘fire engine of the Balkans’ because we were always rushed from hot spot to hot spot. Our territory included Yugoslavia, Bulgaria, Romania, Greece, and Albania,” Horst explained.

Helga Schwermer returned from Stettin to Spandau with her son in 1944. The Soviets were pushing toward German territory, and it was no longer safe near Stettin. Back home, she was living next door to her parents and enjoyed their support, as well as her husband’s ongoing income from the Lufthansa office (though Horst was away in the army). She even belonged to a club of ten to twelve young wives who went to the same air-raid shelter together on a regular basis.

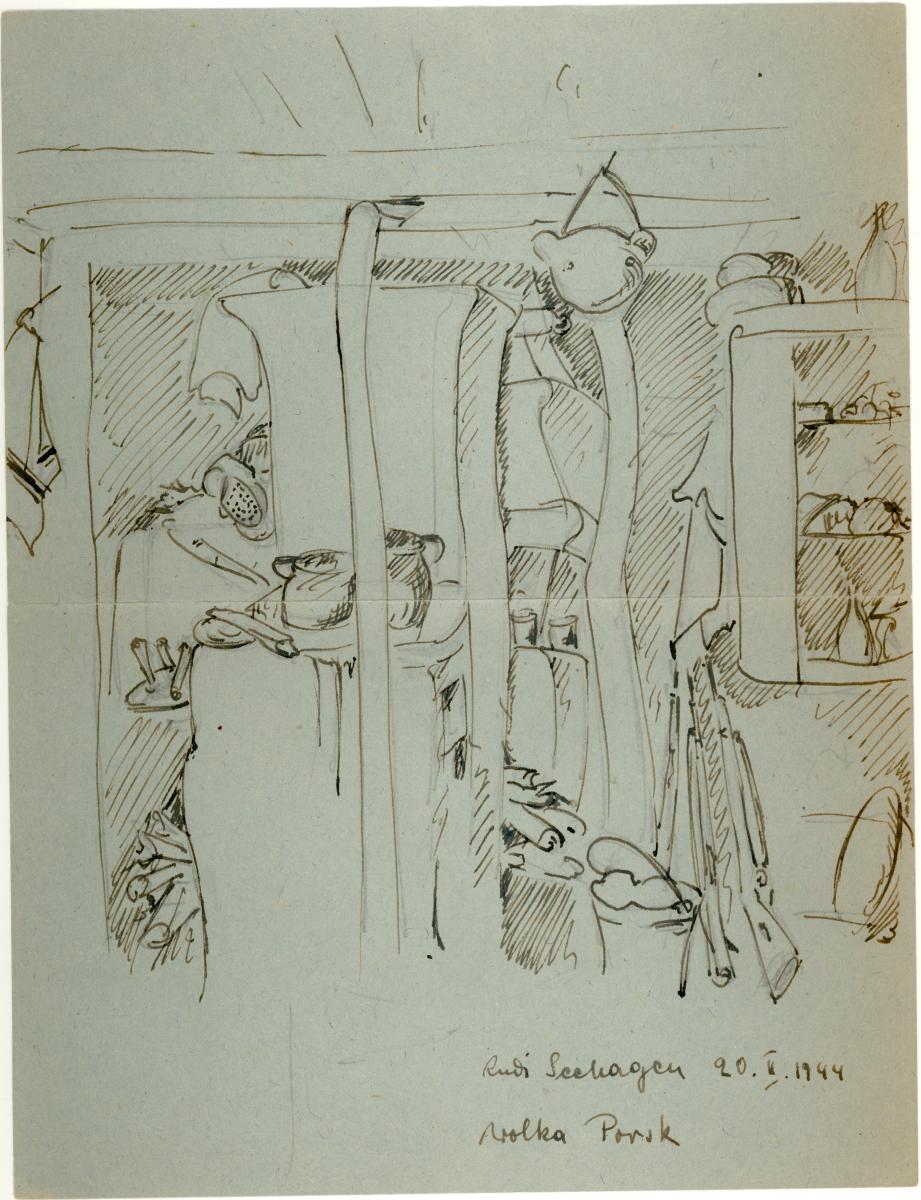

By 1943, the Reich war effort needed every healthy young man. Rudi Seehagen’s exemption was not extended that year, and he was inducted into the Reichsarbeitsdienst. He served with a work unit for three months along the coast of Estonia. Following his release from the RAD, he enjoyed a few days at home before his draft notice arrived. He reported to the local Wehrmacht office and was asked which branch of the military he wished to serve with. Rudi reported having had a serious accident that nearly cost him a foot a few years earlier and requested to be assigned to any unit but infantry. Three days later he was in uniform and on his way to Kobel near the former Polish border for basic training. From there his unit was transported to partisan territory in Russia where conditions were dangerous. It was soon clear that Rudi Seehagen’s request to serve anywhere but in the infantry was not to be fulfilled. As he recalled, “When the army advanced, we were in the vanguard; when they retreated, we were the last to abandon the position. I was never wounded because my Heavenly Father always protected me, but some of my comrades were hurt.”

Rudi Seehagen made this sketch of his temporary quarters in Russia in 1944. (R. Seehagen)

Rudi Seehagen made this sketch of his temporary quarters in Russia in 1944. (R. Seehagen)

Because many German soldiers routinely drank alcohol and smoked, Latter-day Saint soldiers were often under pressure to do the same. Rather than give in, Rudi Seehagen traded his cigarette rations for other food items and successfully resisted temptation. He also avoided another problem: stealing. When his buddies raided local farms and stole food from the Russian inhabitants, Rudi did not go along. He already had enough to eat, thanks to his cigarette trades.

Horst Schwermer also enjoyed the advantages of observing the Church’s standards for health, as was evident from an incident at Easter, 1944. His unit had moved into Hungary, and he stopped one Sunday for a drink with his buddies at a country inn:

The boys ordered a beer, and I ordered a glass of milk. This was my national drink. And the boys got their beers, and it took a little longer for me to get my milk, and when it came [the host] had a big plate and a big piece of cake on it and a glass of milk. So when the boys said, “Oh my gosh, that will cost you,” I said, “It doesn’t matter, but it will taste good.” And then [the innkeeper] came to collect the money from all the boys. “Okay, how much do I owe you?” I asked him. “Nothing, you are my guest.”

Because the Reich was becoming desperate for soldiers, Wolfram Dittrich was only in the RAD for two months at the age of sixteen before he was drafted into the army and trained in tank warfare. Wolfram’s unit was then sent to the front to stop the British advance in northwest Germany. “My entire unit consisted of 16-year olds,” he recalled. “In Rheine at the river Ems we first met the British in combat, and after a short time, only twenty-four of us were still alive.” He was soon a British POW and barely seventeen years of age.

Walter Kuefner was only eleven years old when the Red Army surrounded Berlin in April 1945. Despite his youth, he was trained to defend the Fatherland. He recalled: “Just before the end, I was trained to shoot a Panzerfaust [bazooka]. There was a captured English tank about one hundred feet from our trench, and we were supposed to hit it in our training.” Fortunately, he was never forced to use the weapon in combat and did not participate in the fight against the invaders.

Horst Schwermer had been fortunate to attend meetings in the Spandau Branch for much of the war (a rarity among young Latter-day Saint men in Germany). In early 1945, he was sent to the Eastern Front, which at the time was already on German soil—just fifty miles east of Berlin. Horst found an opportunity to meet with the Saints in the Frankfurt on Oder Branch, where a Brother Butkus presided over the meetings. Because many of the members had already fled from the approaching Red Army, attendance was sparse. All during the war, Horst, a priest in the Aaronic Priesthood, carried his scriptures.

Horst Schwermer’s thirtieth birthday, April 29, 1945, came just ten days before the end of the war. At the time, he was part of the headlong retreat of a decimated German army trying to slow the final Soviet drive toward Berlin. He dispatched two successive messengers to tank squadrons at the front, but both failed to return. Therefore, he found a bicycle and set out to deliver the message in person. While talking with the tank crews in the dead of night, he suffered a grievous wound:

I was sitting on my bike, my right foot on the ground, the left one still on the pedal. And then I felt something, and I fell on my face. And I tried several times to get up, and fell down again. And then I reached down with my hand, and I found out, yes, there was nothing below the [left] knee.

A round fired by a Soviet tank had severed his leg. During the hours that followed, Horst lay on the ground and worried about bleeding to death. His first impression was to ask his comrades to shoot him rather than leave him to the enemy. Then he prayed, asking his Heavenly Father, “Why me?” The response was, “You know why!” Then he prayed that his family (now including two sons) might be protected. He never lost consciousness, and when the sun came up the next morning, he was discovered by German soldiers, who loaded him into their car. During the evacuation, the Soviets overtook the group, and they became prisoners. Fortunately, the invaders had relatively good medical personnel, but Horst was placed at the last of the line, and the supply of ether was nearly gone when it came time to operate on his leg. “I took one good, deep breath [of the ether] but was conscious again before they finished.”

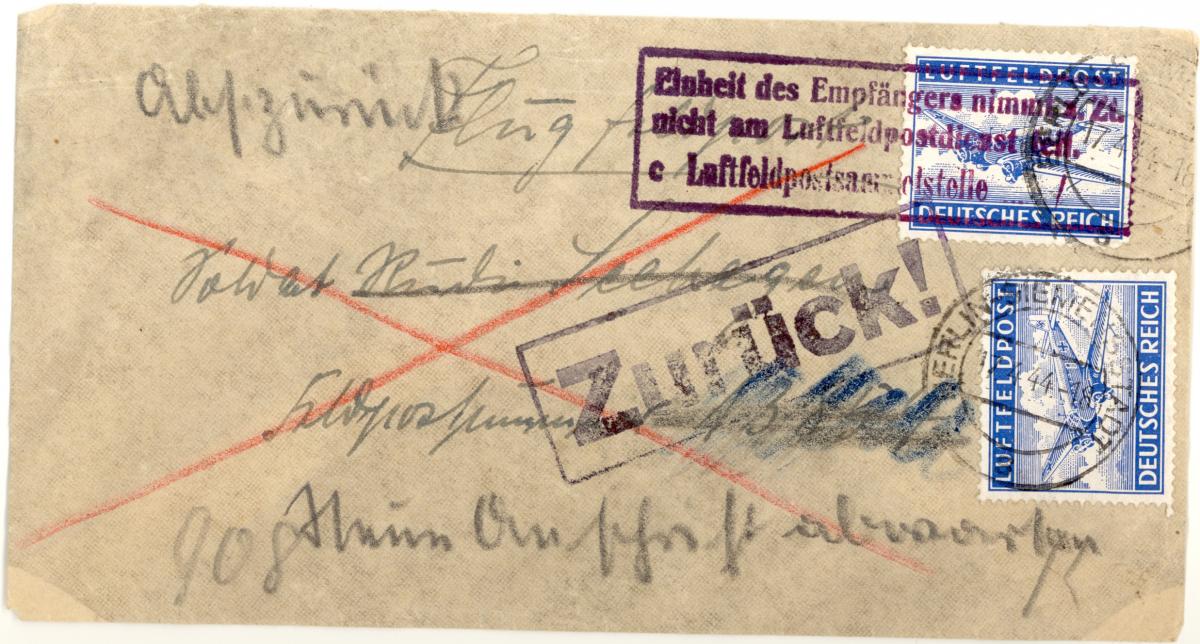

The Seehagen family sent this letter to Rudi in the Soviet Union in 1944, but it was returned as undeliverable ("Zurück!"). He could not be located at the time. (R. Seehagen)

The Seehagen family sent this letter to Rudi in the Soviet Union in 1944, but it was returned as undeliverable ("Zurück!"). He could not be located at the time. (R. Seehagen)

On March 16, 1945 (seven weeks before the war ended), Rudi Seehagen was one of thirteen soldiers cut off from the main German force by the advancing Red Army:

We had held up an entire battalion of Russians for hours. When we ran out of ammunition for our rifles, we used our small arms. Our lieutenant wanted to commit suicide, but I talked him out of that. I told him he might get home someday, otherwise the Russians might do the job for him [kill him]. We destroyed our guns so the Russians could not use them. We used up our last ammo; then we stood up and put our hands in the air. The Russian’s political officer shot one of our officers immediately; then he told his soldiers to pursue our retreating army. They didn’t want to because they were so scared of our army, so he shot five or six of his own men.

Being a prisoner of war was no privilege, but Rudi Seehagen was at least alive. During the next three weeks, he was given almost nothing to eat, and his only source of water was snow. He had no mattress to sleep on and preferred a flat board to the bare ground. On one occasion, the prisoners were being transported to the east by train and were attacked by German fighter planes. Rudi and his comrades dropped to the floor in the aisles while bombs landed to either side of the train. “When we got up, we found that the seats had holes from the shrapnel. I was protected all of the time.”

In contrast, Wolfram Dittrich was treated very well by his British captors. Although he was moved about constantly from camp to camp, he was always allowed to leave the camp for a few hours now and then.

The plight of a young mother with an absent husband was a sad one in Germany in 1945. After the Red Army conquered Berlin, Helga Schwermer and other women in her neighborhood were herded into a large house and ordered into the basement. Soviet soldiers came by constantly to pick out women for their entertainment. They had taken the women’s identification papers and used them to call out the names of their next victims. Helga described the situation:

Every time they would rattle their keys and come into the basement to get another woman, I would take Jürgen and put him on my lap and say, “We’re sick,” and try to scare them off. And young girls age twelve from this group, [after they were assaulted] they killed themselves. They went in the nearby [pond] the next day.

Until July, 1945, Horst Schwermer remained in the infirmary of a Soviet prisoner of war camp recovering from the loss of his leg. He had developed gangrene, and a second amputation was needed; his entire left leg was lost, but his life was saved. During his recuperation, his wife, Helga, was fortunate to learn of his whereabouts, as she recalled:

A German woman who had worked in a Russian prison hospital came to Spandau and told me that my husband was in a Russian prison camp and she was supposed to tell me. I think she might have said that he was an amputee, which at that time sounded wonderful because that meant he was alive!

Determined to learn of the condition of her husband, Helga first sent her father to the Soviet POW camp in Salow (100 miles north of Berlin) to see Horst. Then she and her mother undertook the dangerous journey through territory occupied by the Soviet Army, where sexual assault was a constant threat. After spending the night on the floor of a local farmhouse, the two women sneaked up to the fence surrounding the prison camp and gave the guards some milk, bacon, and cigarettes. Moments later a medical officer appeared and instructed them to wait there. He came back with a nurse’s uniform for Helga to wear, which ruse enabled her to pass the guard station and enter the camp. The tension was high, as she recalled:

I’m sure I must have been shaking, because they looked at the passport, and they looked at me, but they let me go through. And then I went to [Horst] . . . He was only skin and bones. But he was one of the few soldiers that hadn’t cut his curly hair.

In July, Horst was released from prison. He had shrunk from 180 to 96 pounds, and the Russian medical personnel decided that he would not survive the trip to the Soviet Union. He was driven to a railroad station and boarded a train to Berlin. The sight of the devastated city, American soldiers, and the sound of music from the rubble elicited an emotional response: “I cried and cried. On one of the sticks [crutches], I had tied a piece of bread, and on the other end I had tied my triple combination.” He was denied entry to the streetcar because he had no money. Fortunately, a kind woman bought him a ticket, and he rode from downtown Berlin across town to Spandau and a glorious reunion with his wife, Helga, and his two sons.

While thousands of German soldiers were imprisoned in Russia until 1949 and many as late as 1955, Rudi Seehagen was blessed to be released very early from that miserable existence. He had not been allowed to write even one letter home to the parents who had been told that he was missing in action. On October 31, 1945, he was set free in Frankfurt on Oder, just seventy miles from Berlin. Due to the sporadic railway traffic, he needed fully three days to get to the Reich capital that had been bombed beyond recognition. He remembered his homecoming vividly:

The next morning was Sunday [November 4, 1945], and I found my way home by streetcar and subway. I only weighed eighty-six pounds at the time, so I had trouble going up and down the stairs to the trains. When I got off the last streetcar, I ran right into a sister from our branch who was on her way to church. While I went on home, she hurried to church to tell my father I had returned. He had been Sunday School president for years, and very faithful, but that day he told everybody: “You stay here and have Sunday School; I’m going home to see my son!”

On New Year’s Day of 1946, Wolfram Dittrich was released from his captivity under the British near Stade (across the Elbe from Hamburg). He eventually rejoined his parents, who had moved to a town north of Berlin. As he later explained:

Being home in Falkensee again was wonderful, except that the Russians were there. They occupied many of the houses and that was not pleasant. Back in the branch, I realized that not many things had changed. The members who were there before and during the war were also still attending and doing well.

The members of the Spandau Branch had been very fortunate during the war. Despite their proximity to critical war industries and to the Reich capital, and despite the ferocious battle in which the Red Army conquered the metropolis, the meeting rooms and members’ apartments still stood when the smoke and the dust cleared. Following Germany’s official capitulation on May 8, 1945, life in the Spandau Branch went on as before.

According to Helga Schwermer, “I wouldn’t call it a hard life [in 1945]. We didn’t know any better. I still had my parents, I knew [my husband] was alive, and sure, we were hungry, but everybody was—you weren’t any different. And we still went to church every Sunday.”

In Memoriam

The following members of the Spandau Branch did not survive World War II:

Horst Willy Franz Knoll b. Spandau, Brandenburg, Preussen 7 Oct 1924; son of Wilhelm Richard Paul Knoll and Emma Anna Emilie Zastrow; bp. 4 Nov 1932; k. in battle Russia 9 Dec 1943 (R. Seehagen; IGI)

Heinz Werner Konrad Schulze b. Spandau, Brandenburg, Preussen 7 Mar 1938; son of Konrad Heinz Werner Schulze and Marie Margarete Emilie Purann; d. diphtheria Berlin, Preussen 11 Jan 1944 (R. Seehagen; IGI)

Konrad Heinz Werner Schulze or Schumann b. Spandau, Brandenburg, Preussen 12 Feb 1915; son of Reinhold Adolf Konrad Hoffmann and Clothilde Emilie Frieda Schumann; bp. 22 May 1922; m. Spandau 4 Jan 1937, Maria Langner or Purann; 2 children; corporal; k. in battle near Stalingrad, Russia 14 Nov 1942 (R. Seehagen; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Johann Erich Tobler b. Berlin, Brandenburg, Preussen 26 Dec 1891; son of Johannes Paul Gustav Tobler and Hulda Ottilie Brebach; bp. 15 Apr 1925; m. Berlin 29 Feb 1936, Carola Elisabeth Thiemer; k. in battle Spandau, Berlin, Preussen 22 Apr 1945 (CHL Microfilm No. 2458, form 42 FP, Pt. 37, 1949 list: 1378–79)

Hermann Ernst Albert Vogler b. Bredereiche, Brandenburg, Preussen 3 Jul 1891; son of Hermann Ernst Albert Vogler and Friederike Charlotte Hagen; bp. Spandau, Brandenburg, Preussen 17 Apr 1924; m. Belzig, Zauch, Brandenburg, Preussen 9 Jul 1918, Anna Auguste Uebe; 2 children; k. in battle Spandau, Brandenburg, Preussen Apr or May 1945 (R. Seehagen; IGI)

Auguste Zastrow b. Sabow, Pyritz, Pommern, Preussen 25 Apr 1869; dau. of Friedrich Zastrow and Friedricke Bludorn; bp. 10 Oct 1910; d. Berlin, Preussen 13 Oct 1939 (Stern No. 23, 1 Dec. 1939, 372; IGI)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Rudi Seehagen, interview by the author, Sandy, UT, March 9, 2006.

[3] Wolfram Dittrich, telephone interview with Jennifer Heckmann in German, January 25, 2008. German summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[4] Walter Kuefner, interviewed by Michael Corley, Salt Lake City, February 22, 2008.

[5] Helga Abel Schwermer, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, December 8, 2006. See the description of the Jungvolk and Bund Deutscher Mädel programs in the Introduction.

[6] Horst Schwermer, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, December 8, 2006.

[7] When Helga Schwermer returned from Stettin, she found it difficult to get the visitors to leave the apartment, because the air raids over Berlin were beginning to take a serious toll on housing space.