Berlin Schöneberg Branch, Berlin District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 86-93.

Covering most of the southwest portion of metropolitan Berlin, the Schöneberg Branch may have been the most expansive of the six branches in the capital city. On the north, it included the mission office at Händelallee 6 and the Tiergarten Park. At the southwest extreme, it bordered the Brandenburg-Potsdam Branch.

Berlin had experienced a veritable golden age in the 1930s. Under the National Socialist government, the country’s economy had blossomed and its international status had also prospered. The Olympic Games of 1936 had invited the world to a Berlin that featured impressive new structures along broad avenues.

Wolfgang (Herbert) Klopfer was born in this Berlin in February 1936—just as the Winter Olympic Games began.[1] His earliest memories are of this huge city with its superb transportation system, parks, forests, and lakes. His family lived in the mission home at Händelallee 6, and the beautiful Tiergarten Park began literally across the street from the picture window of the Klopfer apartment. Herbert remembered that . . .

the huge city park [Tiergarten] provided unlimited opportunities for childhood fun and outdoor recreation. A playground of sandboxes amidst a forest of beautiful trees and wide open green areas suitable for all kinds of ball games was so close to home that we could see our home from where we were playing and hear our mother calling for us from our balcony. It was a quiet neighborhood. . . . a country environment [that] made life in the big city very happy and satisfying.[2]

The Klopfer family attended church in the Schöneberg meeting rooms at Bülowstrasse 82 in the first Hinterhaus. Ingrid Bendler (born 1926) and her mother were also members of that branch. While the Klopfers could walk about one-half hour to church, the Bendlers came from an upscale neighborhood near Grunewald, far to the west, and needed public transportation to get to Bülowstrasse in about an hour. Ingrid remembered the rooms being on the fourth floor in a building that she was not proud to invite a friend to visit. The average attendance was about forty persons.[3]

| Schoeneberg Branch[4] | 1939 |

| Elders | 5 |

| Priests | 3 |

| Teachers | 1 |

| Deacons | 3 |

| Other Adult Males | 18 |

| Adult Females | 97 |

| Male Children | 2 |

| Female Children | 6 |

| Total | 135 |

Ingrid Bendler was the only person of her age in a branch with very few children. Fortunately, Fritz Mudrow, the branch president, took her under his wing and gave her many opportunities to serve:

I was a Sunday School teacher when I was twelve. The Klopfer boys were in my class. . . . [President Mudrow] tried to keep me busy. Almost every Sunday, I had to stay at the back door and greet the people coming in. And he would have me give a poem, sing a song, something just to keep me going.

At the age of ten, Ingrid was inducted into the Jungmädel program of the Hitler Youth. She enjoyed the association with other girls, the activities, the trips, and the events that required the girls to miss school. The uniform was “a white blouse, blue skirt, brown jacket, and a black neckerchief. . . . When I was 15, I was not interested in that program any more and I didn’t participate any longer. There was never any pressure to join the [Nazi] Party or be active in the Hitler Youth.”[5]

Young Herbert Klopfer recalled the early part of the war:

“For a young person that was exciting. For the first two years the war had been reasonably easy for us. Even though we were constantly bombed and had to spend many nights in the basement.” The mission home was just a few blocks from the business district of western Berlin, and the air raids in the neighborhood were very frequent.

A common pastime among elementary school children in large German cities was collecting pieces of shrapnel after bombing raids. As he later explained about the ways little boys had fun during the war, “Numerous splinters of grenade shells and fragments of bombs accumulated all over our street and in the park as they fell from the air. These were favorite ‘toys,’ but also extremely dangerous because of their very sharp and cutting edges.”[6] The children usually kept their collections in shoe boxes and traded them on the school playground.

In 1942, a number of young adults moved into the Schöneberg Branch. These included sisters Inge and Fränzi Otto, each of whom married a soldier soon after their introduction in the branch. According to Ingrid Bendler, “We really celebrated those weddings, we danced all night. We came home at six in the morning and all of us showed up at ten o’clock for Sunday School.” Another new member of the branch, soldier Willi Werner, was ten years older than Ingrid, but they spent every evening of his three-week furlough together, and he became her first love.[7]

Mission Supervisor Herbert Klopfer and his family celebrated the first Christmas of the war in their apartment in the mission home. Erna Klopfer’s parents (Brother and Sister Hein) joined them for the occasion. Note the blackout curtain rolled up at the top of the window (I. Reimer Ebert)

Mission Supervisor Herbert Klopfer and his family celebrated the first Christmas of the war in their apartment in the mission home. Erna Klopfer’s parents (Brother and Sister Hein) joined them for the occasion. Note the blackout curtain rolled up at the top of the window (I. Reimer Ebert)

Ingrid Bendler was in school during the first four years of the war. Following her graduation from business college in the spring of 1943, life became a bit more challenging, as she was called upon for government service. Her mandatory Pflichtjahr (year of duty) assignment placed her in a private home as a nanny for essentially no pay. However, she had Sundays off and was able to attend church. When the attacks on Berlin increased in frequency and severity, the family moved out of town, and Ingrid’s term of duty ended ahead of schedule.

Herbert Klopfer remembered air raid alarms as often as twice each night. Whether in the basement or in their living room, his mother, Erna, gathered her sons close and they prayed. Sometimes the sister missionaries who lived upstairs joined them:

They did not want to leave us alone. We huddled together, listening to the engines of enemy airplanes and hearing and feeling the rattling of windows and the detonations of bombs bursting nearby. Our hearts were filled with prayers, always hoping that the next bomb would again pass us up.

In early 1943, mission supervisor Herbert Klopfer (a soldier on active duty) followed the government’s recommendation to move his family out of Berlin. During one of his furloughs, he took them and some of their property to the home of his parents in Werdau, Saxony, four miles west of Zwickau. His wife, Erna, and their two sons would live there for the next seven years. All four of the boys’ grandparents lived under the same roof, as did their aunt.[8]

A branch outing in the forest in the early years of the war (I. Bendler Broughton)

A branch outing in the forest in the early years of the war (I. Bendler Broughton)

The Klopfer family’s move to Werdau was providential. On November 21, 1943, bombs partially destroyed the mission home on Händelallee in Berlin. Brother Klopfer’s counselors, Richard Ranglack and Paul Langheinrich, mobilized members of the Church to move most of the mission office property to the apartment house in which Brother Langheinrich lived. This was inspired action because everything the Klopfers had left behind during their move to Werdau was lost the very next night when the mission home was totally destroyed by phosphorus bombs.[9]

On November 9, 1943, Ingrid Bendler was drafted into the Reicharbeitsdienst and sent to Költschen (east of Berlin):

We had to wear a uniform, live in barracks, and help the farmers in a little farm community. . . . I cleaned the stables, helped with the harvest and threshing. I also helped with making sausages. . . . There was a daily fight with the geese . . . I liked to learn how to bridle the horses.”[10]

It must have been an interesting and exhausting life for a city girl, but Ingrid was pleased to be away from the big city that was being pulverized from the air on a regular basis. In an apparently contradictory sense, she later suggested that it would have been better to be in Berlin than in the countryside: “It is just so much easier to be in the middle of things and experience them yourself than to be far away and imagine how bad it would be.”[11]

Less than a month of her term in the Reichsarbeitsdienst had passed before Ingrid Bendler learned of the death of her dear friends, Inge and Fränzi Otto, and their mother—victims of an air raid. The funeral was “heartbreaking” and left her with a “downright lost feeling.” Their burial was in a mass grave.[12] Wilhelm Werner (a half-brother of Inge and Fränzi) had come from the Eastern Front to attend the funeral. He and Ingrid were engaged before he left, but the two did not meet again until his release from imprisonment in Russia in 1949.

The air raids eventually reached the Bendlers’ neighborhood, and even when the bombs missed their house, the air pressure of nearby detonations shattered their windows. Ingrid’s father worked hard to replace the glass in those windows. While most people in that situation simply covered the window frames with cardboard or wood, Mr. Bendler used glass-wire until he could get real glass, which he did several times a week. He simply refused to give up, insisting: “That’s what the enemy wants; they want us to give up.” During one attack, Ingrid’s mother was hiding in a basement, and the woman sitting next to her was killed. Sister Bendler was “very shook up. Her nerves were shot.”[13]

Herbert Klopfer told of several occasions when his parents were nearly killed, even after leaving Berlin. Once they were on the train from Berlin to Werdau. Just five minutes after the train departed the main station in Leipzig, the city was hit in a massive attack that took the lives of several thousand people, many of whom were trapped in railroad cars inside the main station.[14]

The typical Berlin apartment house in 1939 was built about 1900. It was five stories tall, had twelve-foot ceilings and two apartments per floor.

The typical Berlin apartment house in 1939 was built about 1900. It was five stories tall, had twelve-foot ceilings and two apartments per floor.

In 1944, Ingrid Bendler was informed that her term of duty with the Reichsarbeitsdienst had been extended by one year. She was asked to become a leader and to make the service her career. However, because she was totally cut off from the Church under those circumstances, she turned down the offer. The government responded with an unofficial punishment—assigning her to be a school teacher in East Prussia. This put her very close to the invading Soviet Army.

In Fröhlichshof, East Prussia, Ingrid was given charge of a class of eighty pupils from six to fourteen years of age. Without any formal teacher training (a total of three days), she had several wonderful experiences in elementary education and became a favorite among the farming population in that small town. One experience was not connected to school but was closely related to the standards of morality taught to her by a faithful mother and her teachers in the Schöneberg Branch:

While I was teaching school in East Prussia, the [Waffen-] SS, that was the elite group of German [soldiers] came through the village. They were all very good-looking young men. They were strong and intelligent. All of them were handpicked. They would come to my door and try to conquer me. I had befriended a very nice shy young man; he told me that all the guys had a bet going . . . that I could not withstand their charms and [would] go to bed with them. . . . I was true to Willy [Werner] and stayed with the teachings of the Church. So I fought them off and I won. Had I been permissive, I would probably have lost the guidance of the Spirit.[15]

After spending Christmas 1944 with her parents in Berlin, Ingrid returned to Fröhlichshof where she heard terrifying rumors of Soviet atrocities committed on German soil. She contacted the local military commanders to express her fears and was allowed to leave on January 18, 1945, traveling with the army to the provincial capital of Königsberg. There she was able to squeeze into a train with several thousand people desperate to go west. The trip to Berlin usually took ten hours, but under the confusion of the time, it took Ingrid three days and three nights to get home.

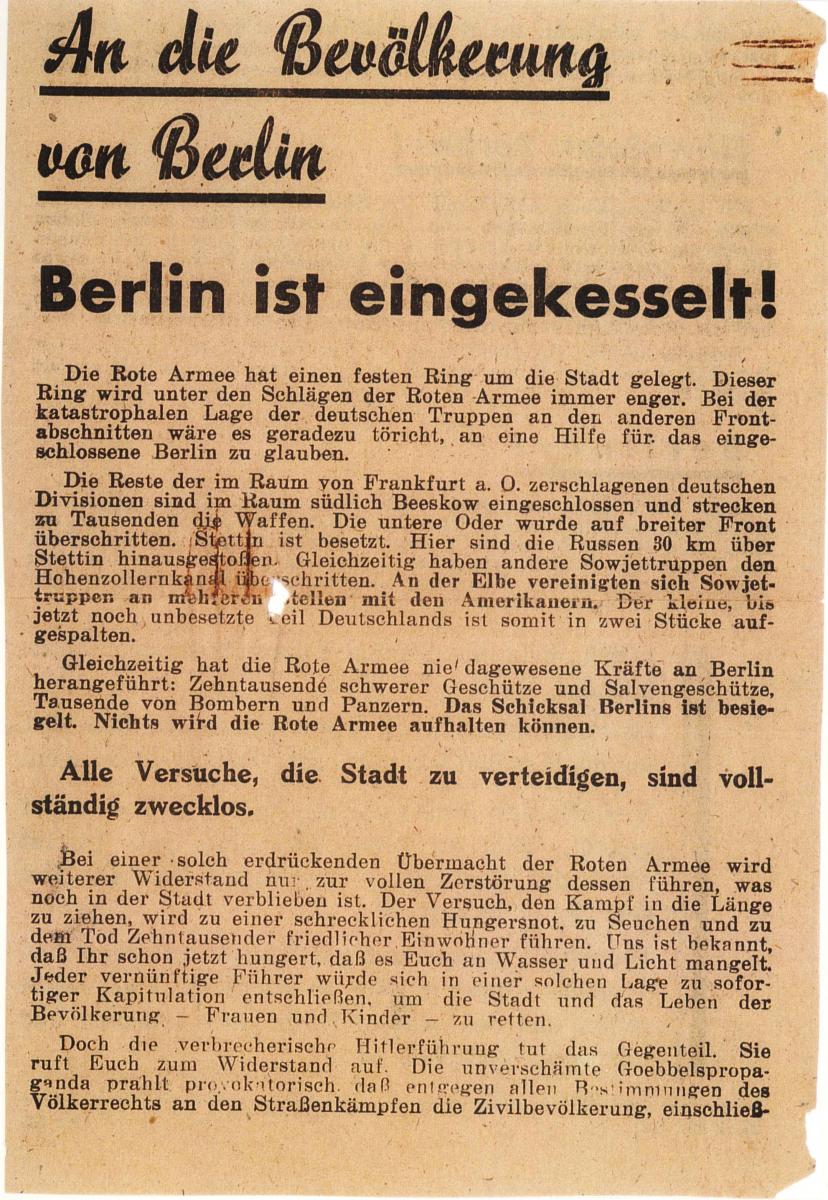

Back in Berlin, Ingrid worked in an office where she dispensed ration stamps. When the Soviet invaders approached the city, they dropped flyers to convince the citizenry that resistance was futile. Artillery shells were soon bursting near the ration stamp office, but Ingrid and the staff continued to work: “When the firing and shelling would get too close we would duck a little, but never could or would we leave our desks, those ration stamps needed to be protected. People wanted to get everything they were allowed to receive.”[16]

“To the residents of Berlin: Berlin is surrounded! Any attempt to defend yourself is totally futile.” This flyer was dropped over the city by Soviet planes in the last week of April 1945 (R. Berger Rudolph)

“To the residents of Berlin: Berlin is surrounded! Any attempt to defend yourself is totally futile.” This flyer was dropped over the city by Soviet planes in the last week of April 1945 (R. Berger Rudolph)

Ingrid’s father was a carpenter employed by the city, so he took his family to city hall where they stayed for the next few weeks in relative comfort. Mr. Bendler had been mustered into the Volkssturm but simply laid down his rifle one day and walked away from the fighting. He felt that dying under those circumstances would be senseless.[17] The carnage everywhere in Berlin was shocking and depressing. Ingrid remembered seeing a dead horse in the street and local residents hurrying to cut hunks of meat from the carcass. In a worse situation, she witnessed the following:

While crossing a very busy intersection, I would always see a flat—very dirty piece of cloth that looked like a piece of uniform. It was no bigger than a pillowcase. There was a sweet sickening smell at the spot. We crossed it many times. One time a neighbor of mine investigated and kicked this cloth with his foot. Out came a finger with a crunched-up wedding ring. No one could ever think this was a human being. It must have been a soldier who was run over by a tank. A clean-up crew picked this “leftover” human being up in one shovel, it was unrecognizable. This was a powerful lesson. Men are nothing by themselves. To literally see a human being reduced to a shovelful of nothing was a sobering experience. It reinforced in me the feeling of dependency to my Father in Heaven. I never felt important after that.[18]

Erna Klopfer and her sons experienced the end of World War II in the relative safety of the small town of Werdau, but her husband, the mission supervisor, had been reported missing in action the previous September. She did not learn of his fate until an emaciated soldier released from a POW camp in the Soviet Union in September 1948 knocked on her door in Werdau. He reported having been at Herbert Klopfer’s side in a squalid camp near Kiev, Ukraine, when Brother Klopfer passed away on March 19, 1945. Brother Klopfer’s health had deteriorated due to hard labor in a salt mine.[19]

The battle for Berlin ended on Ingrid Bendler’s nineteenth birthday, May 2, 1945. In the rubble of the Reich capital, she still went to church, though it now took two hours to walk—one way. She later wrote the following about the Schöneberg Branch at the conclusion of World War II:

Most everyone had lost everything. That didn’t seem to matter. We rejoiced in being together. More and more members would come out of the ashes. Since we still had Sunday School in the morning and sacrament meeting in the evening I just stayed there all day. We rejoiced in being with each other and to see how many of the Saints had survived. Everyone had a story to tell. We were happy to be alive. All our relatives made it through the ending of the war. My brother and family was [sic] o.k. also.[20]

In Memoriam

The following members of the Schöneberg Branch did not survive World War II:

Gerhard Bellmann b. Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 11 Aug 1897, son of Wilhelm Bellmann and Marie Lippmann; sergeant first class; k. in battle 10 Apr 1945; bur. Costermano, Italy (CHL CR 375 8 #2459, 1034–35; www.volksbund.de)

Gerd Gustav Hermann Burkhardt b. 24 Jul 1920; son of Wilhelmine Marie Precht; bp. 20 Jun 1930; Luftwaffe corporal; shot down 26 Feb 1941; bur. Landeseigener Cem., Neukölln, Berlin, Preussen (Sonntagsgruss, No. 19, 11 May 1941, 76; FHL Microfilm 25733, 1930 Census; IGI)

Heinz Bernhard Hillig b. Limbach, Germany 25 Mar 1911; son of Bernhard Hillig and Marie Flohr; k. in battle Poznan, Poland 1942 (CHL CR 375 8 #2459, 1014–1015; www.volksbund.de)

Auguste Wilhelmine Holz b. Gross Hoppenbruch, Ostpreussen, Preussen 18 or 28 Jun 1862; dau. of Gottlieb Holz and Wilhelmine Priess; bp. 8 Aug 1925; m.—Jaske; d. senility 18 Oct 1939 (CHL CR 375 8 #2458, 1939 data; FHL Microfilm 271366, 1930/

Karl Herbert Klopfer b. Werdau, Sachsen 14 May 1911; son of Max Alfred Klopfer and Marie Hedwig Schaller; bp. 22 Jun 1923; ord. elder; East German Mission Leader Aug 1939-; m. Beuthen, Brandenburg, Preussen 22 May 1934, Erna Luise Hein; 2 children; d. field hospital near Pushka, Kyev, Ukraine, USSR 19 Mar 1945 (H. Klopfer; letter from CO, CHL CR 27140; IGI; FHL Microfilm 271380, 1935 Census)

Walter Oskar Kramer b. Berlin, Preussen 10 Feb 1877; son of Johann Kramer and Louise Beck; m. Olga Wagner; k. air raid Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 5 Mar 1945 (CHL CR 375 8 #2459, 1034–1035)

Heinz Paul Wilhelm Mueller b. Königsberg, Ostpreussen, Preussen 7 Jan 1902; son of Paul F. Müller and Bertha Kopenhagen; d. 13 Nov 1939 (CHL CR 375 8 #2460, 416–17)

Olga Wagner b. Marienberg, Germany 10 Feb 1877; dau. of Louis Wagner and Marie Mann; m. Walter Oskar Kramer; k. air raid Chemnitz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 5 Mar 1945 (CHL CR 375 8 #2459, 1034)

Walter Hugo Wolf b. Spandau, Berlin, Preussen 30 May 1890; son of Heinrich Wolf and Elisabeth Graneberg; m. 10 May 1919, Martha Marie Anna Nickel; 2 children; d. wounds Spandau 18 May 1949 (CHL CR 375 8 #2459, 1014–15; IGI)

Leonhard Zander b. Aachen, Rheinland, Preussen 9 Dec 1864; son of Johannes Zander and Elisabeth Kutsch; bp. 13 Sep 1919; ord. priest; ord. elder; m.; d. Berlin, Preussen 11 Feb 1941 (Sonntagsgruss, No. 10, 9 Mar 1941, 40; FHL Microfilm 245307; IGI)

Notes

[1] After arriving in the United States in 1951, he changed his first name to that of his father, Herbert Klopfer, the supervisor of the East German Mission from 1939 to 1945. See the East German Mission chapter.

[2] Herbert Klopfer, “Childhood in the Big German City of Berlin [1936–1943],” 3 (unpublished personal history). Private collection.

[3] Ingrid Bendler Broughton, interviewed by the author, Kaysville, UT, February 16, 2007.

[4] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[5] Ingrid Bendler, autobiography, 11 (unpublished). Private collection.

[6] Herbert Klopfer “Childhood,” 4.

[7] Ingrid Bendler, autobiography, 14.

[8] Herbert Klopfer, “Childhood,” 4.

[9] See the East German Mission chapter for additional details about those two nights.

[10] Ingrid Bendler, autobiography, 14.

[11] Ibid., 16.

[12] Ingrid Bendler, autobiography, 16. The two Otto girls had married just months before their death. By the end of the war, their husbands had also been killed.

[13] Ibid., 17

[14] Herbert Klopfer, “Childhood,” 5.

[15] Ingrid Bendler, autobiography, 25.

[16] Ibid., 27.

[17] Ibid., 26.

[18] Ibid., 33.

[19] Herbert Klopfer, “Childhood,” 6. Part of the miraculous report was that the soldier had gone first to Berlin, where by coincidence he had learned that the family was living in Werdau.

[20] Ingrid Bendler, autobiography, 33.