Aschersleben Branch, Leipzig District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 336-9.

The city of Aschersleben is located in the historical Prussian province of Saxony, some fifty miles northwest of Leipzig. Shortly before World War II began, there were only sixty-one members of the Church there. The city had a population of about 35,000 people.

| Aschersleben Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 0 |

| Priests | 1 |

| Teachers | 0 |

| Deacons | 4 |

| Other Adult Males | 9 |

| Adult Females | 45 |

| Male Children | 2 |

| Female Children | 0 |

| Total | 61 |

East German Mission records indicate that the meetings of the Aschersleben Branch were held at Feldstrasse 21A by the end of 1938. Irene Hampel (born 1928) recalled that the rooms were part of a shoemaker’s business. “The branch was permitted to use one main room and two smaller rooms.” As in most other branches, Sunday School was held in the morning and sacrament meeting in the evenings. Irene and her mother walked home between meetings and back again in the evening. They lived about thirty minutes (walking time) from the meetinghouse.[2]

Rolf Richter (born 1930) remembered that branch meeting location all through the war. They began with one or two rooms and eventually expanded to five rooms.[3]

Just days before the war began, Irene came home from school. Her father was at home, and she asked him why he was not at work. He explained that he had been called into the army. His first tour of duty lasted only three months, after which he stayed home until February 1945.

It was common to see large proportions of German branches in those days consisting of women. The Aschersleben Branch may be an anomaly, however, in that 74 percent of the branch members were in this category. There were very few men. According to Rolf Richter, Melchizedek Priesthood holders from neighboring branches or members of the district presidency attended meetings in Aschersleben on a regular basis. He specifically recalled H. Friedler of Magdeburg coming to Aschersleben to take charge of meetings. On March 30, 1940, Paul Wanke became branch president. He had moved from Breslau in Silesia to nearby Stassfurt.

“Until I was fourteen years old I was a member of the Jungvolk,” recalled Rolf Richter:

I was a drummer in the brass band. I was in that group with body and soul. I liked it so much, and music was my life. When the transition [to Hitler Youth at age fourteen] was supposed to take place, my group leader said to the Hitler Youth leaders that I needed to stay in his group. I was lucky that I did not have to [advance].[4]

Irene’s brother, Heinz Hampel, was hoping to serve in the merchant marine. His plan worked shortly before the war started. However, after Germany attacked Poland on September 1, 1939, Heinz was inducted into the navy and became a signal specialist. On one occasion, he was on shore leave when his ship was attacked and sunk. Several of the crew were lost.

The Aschersleben Branch at the end of the war (R. Richter)

The Aschersleben Branch at the end of the war (R. Richter)

When Irene Hampel became fourteen years of age, she was to be inducted into the League of German Maidens. She refused and was threatened by the local police. Her mother came to her defense with the excuse, “She works from dawn to dusk, so there’s no time.” Irene was allowed to miss the meetings if her father wrote a letter requesting her release. He was not a member of the Church, but wrote the letter.

As the war dragged on, attendance at the meetings of the Aschersleben Branch declined. Irene recalled having as few as six persons in attendance. Sometimes, the only man present was an old man of very poor health. Nevertheless, the meetings continued.

There were eight air raids of mention over the city of Aschersleben during World War II.[5] At least 352 apartments were damaged or destroyed in the city and 244 residents were killed. In addition, several hundred foreign workers lost their lives. Irene Hampel recalled that the sirens began to blare one Sunday during a worship service. “We had a prayer then we went on with our meeting. We didn’t have anywhere to go. . . . There were no public shelters anywhere close. Then we heard the bombs falling on another city a few miles away.”

The Hampel apartment was one of those damaged in the attack of March 31, 1945. Irene was not at home, but her mother was in the cellar. A piece of concrete crashed through the roof and landed in one of their beds, but the damage could be repaired.

Rolf Richter was trained in civil defense procedures. He later described those functions:

When there was an alarm, I had to be where my group leader was to make sure he knew when something happened and to see that the lights were all turned off. I also had to go to factories that were attacked and that was the first time that I saw dead people. I did not have to retrieve the bodies.

On April 18, 1945, the American army conquered Aschersleben. There was enough resistance offered by the defenders that several persons were killed in the process. The Americans stayed in the city until May 23, 1945, when the British forces moved in. They in turn were replaced by the Russian army.[6]

Rolf Richter recalled watching the American army moving into town. “They marched past our home with their tanks on both sides of the street. Being little boys, we stood in our doorway watching them. We weren’t scared and they smiled at us. I saw many black people.” When the Soviets came, conditions deteriorated. Rolf described the situation in a single phrase: “I never experienced anything like that!”

“We had enough food under Hitler’s government, but when the Russians came, that all changed,” recalled Irene Hampel.

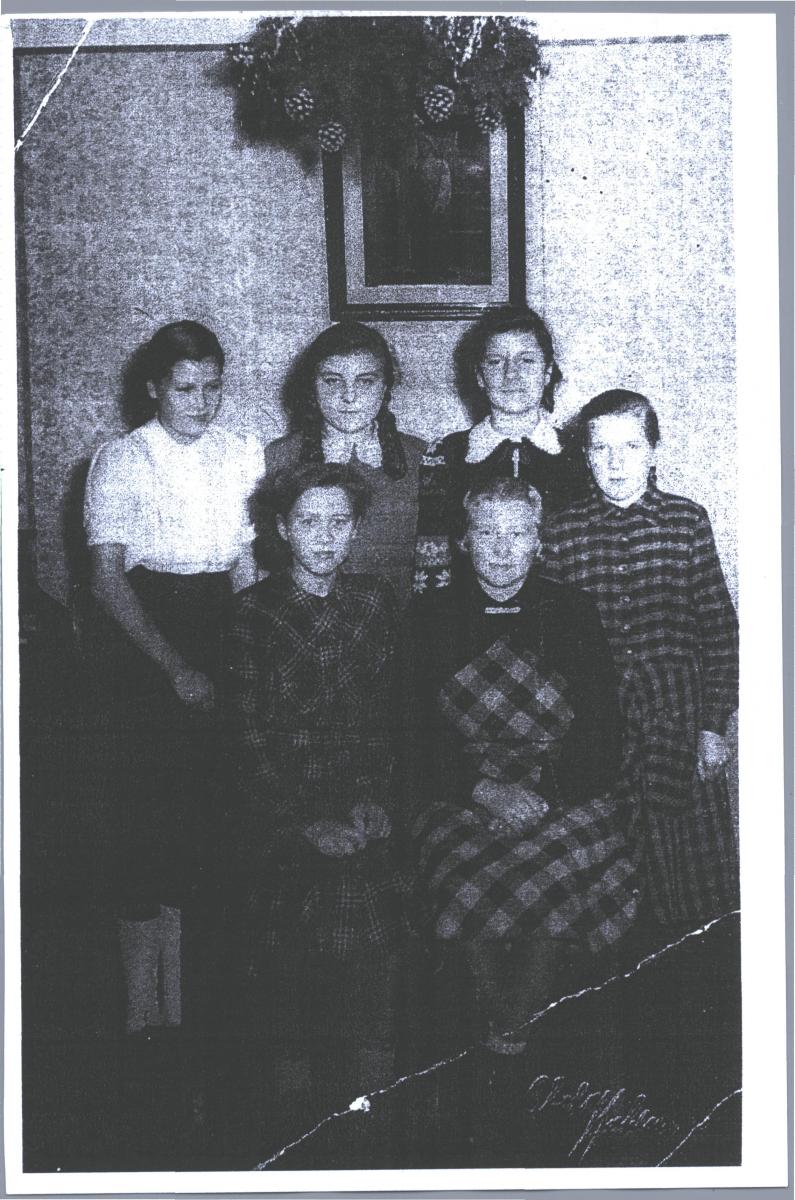

The young women of Aschersleben with their leader, Sister Liebing (R. Richter)

The young women of Aschersleben with their leader, Sister Liebing (R. Richter)

Irene Hampel’s father was taken prisoner by the French and remained in their custody until February 1946. He had been in poor health but was in even worse shape when he came home. Heinz Hampel also returned home safely, arriving in late 1946.

By the end of the war, the auxiliary organizations were no longer holding meetings during the week, but the two Sunday meetings continued to take place, as Rolf Richter later wrote in his branch history. Relief Society, Primary, and MIA began anew in the summer of 1945.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Aschersleben Branch did not survive World War II:

Rudolf Karl Hintz b. 23 Apr 1925; d. wounds 1945 (I. Hampel Kupitz)

Minna Karchner k. air raid Aschersleben, Sachsen 1944 or 1945 (I. Hampel Kupitz)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] Irene Hampel Kupitz, interview by the author, Taylorsville, Utah, March 3, 2006.

[3] Rolf Richter, “Geschichte der Gemeinde Aschersleben” (unpublished history); private collection; trans. the author.

[4] Rolf Richter, interview by the author in German, Aschersleben, Germany, May 31, 2007; summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[5] Angelika Adam, “Seit Zehn Jahren Ehrenbürger,” Ascherslebener Zeitung, April 16, 2005.

[6] Ibid.