Annaberg-Buchholz Branch, Chemnitz District

Roger P. Minert, In Harm’s Way: East German Latter-day Saints in World War II (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University, 2009), 156-63.

The twin towns of Annaberg and Buchholz are located seventeen miles south-southeast of Chemnitz and just six miles from the border of Czechoslovakia. Although geographically isolated in the Erzgebirge Mountains of Saxony, the branch there was strong and active.

Annaberg-Buchholz Branch[1] | 1939 |

| Elders | 15 |

| Priests | 7 |

| Teachers | 11 |

| Deacons | 30 |

| Other Adult Males | 44 |

| Adult Females | 141 |

| Male Children | 13 |

| Female Children | 13 |

| Total | 274 |

The records of the East German Mission show several entries regarding the branch in Annaberg-Buchholz:

Friday, 1 July 1939: “In order to repair the chairs in the Buchholz Branch hall, Chemnitz District, several special meetings were held to enthuse the saints to a united effort to raise money. The result was very good.”[2]

Sunday, 17 July 1938: The Buchholz Branch, Chemnitz District, held a conference.[3]

Saturday, 6 August 1938: The Annaberg Branch choir, Chemnitz District, gave a very successful concert.[4]

Saturday, 8 October and Sunday, 9 October 1938: A branch fall conference was held in Annaberg-Buchholz; Herbert Klopfer [from Berlin] and Elder Roger A. Brown directed the conference.[5]

Sunday, 15 January 1939: The Annaberg-Buchholz Branch moved into a new hall. It was in the same building, but one flight higher.[6]

Sunday, 5 February 1939: An opening program was held in the new branch hall of the Annaberg-Buchholz Branch, Chemnitz District.[7]

Willi Schramm was the branch president. His daughter, Ruth (born 1929), recalled that the members of the branch came from many locations in the Erzgebirge Mountains:

They came from all over. And they came in the winter, with their babies, walking! They had the babies wrapped in the baby carriage—it was just great! In fact, if you didn’t come one or two Sundays [in a row], they [branch leaders] got after you.[8]

Erhard Wagner (born 1917) lived in the small town of Geyersdorf, just less than two miles east of Annaberg-Buchholz. “There were about 1,500 people in the town and six or seven Latter-day Saint families. We had about the largest percentage of membership of any town in Germany. The blood of Israel was very strong in our little town,” he claimed.[9]

Erhard recalled that Relief Society and priesthood meetings were held just before sacrament meeting on Sunday evening, with MIA meetings on Wednesday evenings. “We walked back and forth to church twice every Sunday, one and one-half miles each way,” he later explained. Erhard’s sister, Alice (born 1926), remembered that the walk took an hour and that no bus was available to shorten the time. She also recalled attending Primary after school on Wednesdays and holding group meetings in Geyersdorf on Thursday evenings. She later explained, “We met in different homes. I was always so excited that I was able to go with my parents because I could learn more about the gospel.”[10]

Ruth Schramm lived in Buchholz at Karlsbaderstrasse 19. From her home, she needed about fifteen minutes to go down the hill, across the bridge to Annaberg, up the hill and around the corner to the church rooms at Wilischstrasse 10. Regarding the facility, Alice Wagner later recalled, “We met in a big factory hall on the second floor. On the one side there were only windows and on the other was a door to all the rooms we held the other meetings in.”

Helga Martin (born 1931) recalled seeing pictures of Joseph Smith and Brigham Young on the back walls of the main meeting room. “There was a sign on the street side of the factory that said that we were the Kirche Jesu Christi der Heiligen der Letzten Tage.”[11]

Sunday School was held in the morning, after which most of the members went home for dinner. They returned in the evening for sacrament meeting. Primary meetings were held on Wednesday afternoons after school. Ruth Schramm walked to church with her father on Sundays, but went alone on Wednesdays. “It was a long walk, but it was safe in those days,” she recalled.

In 1938, Erhard Wagner was drafted for two years of service in the German army. At the time, every young man in Hitler’s Germany was required to serve the fatherland. In the summer of 1939, Erhard’s father visited him at the camp in Leipzig where he was completing basic training and told his son what he had heard in BBC radio broadcasts in German from London. Erhard recalled the conversation:

“Son, you’re going to have war really soon. Hitler’s starting a war.” I told him, “Be careful, you have a Nazi living upstairs, and if he finds out [about the radio], you’re gone. He’s a 200 percent Nazi, that guy upstairs.” Two weeks later, on a Sunday, we had to pack everything, march to the Polish border, and on the first of September we were right in [the action]. Nobody had any idea before.

The Annaberg-Buchholz Branch in the 1930s (H. Martin Scharschmidt)

The Annaberg-Buchholz Branch in the 1930s (H. Martin Scharschmidt)

Erhard Wagner had the dubious honor of moving across the border in the first hour of World War II—the German offensive against Poland. He was with an antiaircraft battery that followed close upon the heels of the infantry in the early morning hours of Friday, September 1, 1939. Although his unit marched past dead soldiers of both armies, there was little real resistance and Erhard’s group never fired a shot. The Polish campaign ended in three weeks. From there, they loaded their artillery pieces onto railroad cars and headed westward.

On May 10, 1940, the German army crossed the border into Belgium, the Netherlands, and Luxembourg to begin an offensive that would result in the conquest and occupation of those three countries and eventually France to the south. Again, Erhard Wagner crossed the border on the first day of the campaign but saw no combat until May 19—his birthday—when his unit encountered resistance. “Oh, no, today’s my birthday; maybe it’s my last day,” he thought to himself. He survived the encounter and later had time to enjoy the sights in France. The next move took his unit to the demarcation line in Poland, where the Russians and the Germans had divided the conquered country in 1939. His enlistment term of two years soon elapsed, but there was no discussion of Erhard going home.

Ruth Schramm was one of two LDS children in her school of 500. “Can you imagine what I went through? Everybody else was Lutheran except one Catholic boy. There were a few boys who said, ‘Rutha is a Buddha!’ And Ruth didn’t like that at all!”

Along with the rest of the girls in her school class, Alice Wagner was inducted into the Hitler Youth. In her recollection:

There was a meeting once a week in the evening hours. We had to wear a skirt, a white blouse, and a jacket. It did not bother us. There were no meetings for the Hitler Youth on Sundays, and nobody in school picked on me because I was a member of the Church.

Wolfgang Scharschmidt (born 1928) was also in the Hitler Youth, but the program mattered little to him: “My father did not want us to go and encouraged us to stay home. I always found a reason not to go, and there wasn’t any trouble when I stayed away.”[12]

Mother’s Day in the Annaberg-Buchholz Branch during the war (H. Martin Scharschmidt)

Mother’s Day in the Annaberg-Buchholz Branch during the war (H. Martin Scharschmidt)

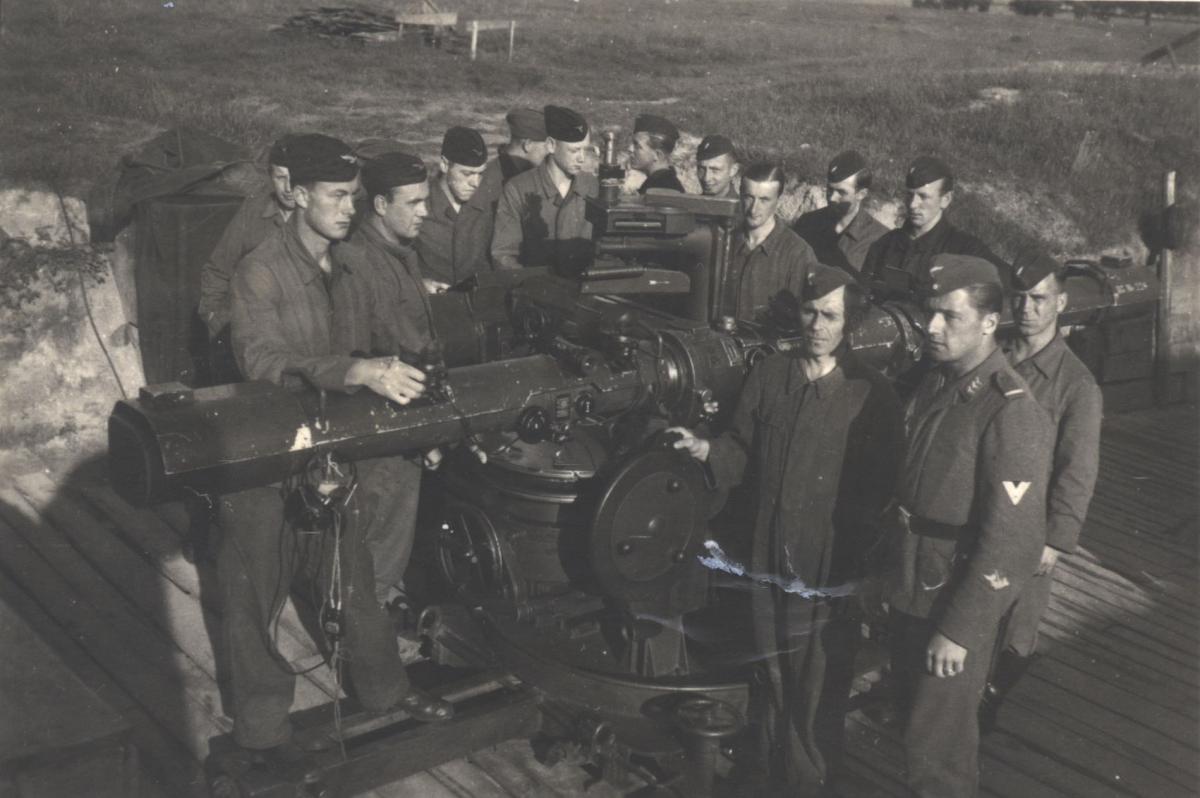

Erhard Wagner was trained in the use of one of the most effective and feared weapons of World War II—the German 88-millimeter howitzer. It could fire a projectile of about two feet in length and three inches in width nearly one-half mile per second. Erhard was responsible for determining the trajectory and the moment of fire. On one occasion in France, his battery of four howitzers shot down in one salvo three airplanes returning to England after a raid over Germany. Regarding his reaction to seeing enemy planes fall from the sky with no parachutes emerging from those planes, he recalled:

War is bad, but how can you feel real sorry about something like that when they come back after killing hundreds in our homeland? They did carpet bombing. Men, women, children, everybody got killed. That’s terrible, you know. . . . We went right . . . to that place where the airplanes had [crashed], and I can’t remember any cheering [about our victory].

In June 1941, the German army launched a massive assault into the Soviet Union. Again, Erhard Wagner was one of the first to cross the border into enemy territory. “When they told us that we were attacking Russia, we couldn’t believe it. We were already fighting a front in Africa, and now we were fighting in the east. . . . It was foolish; we knew that.”

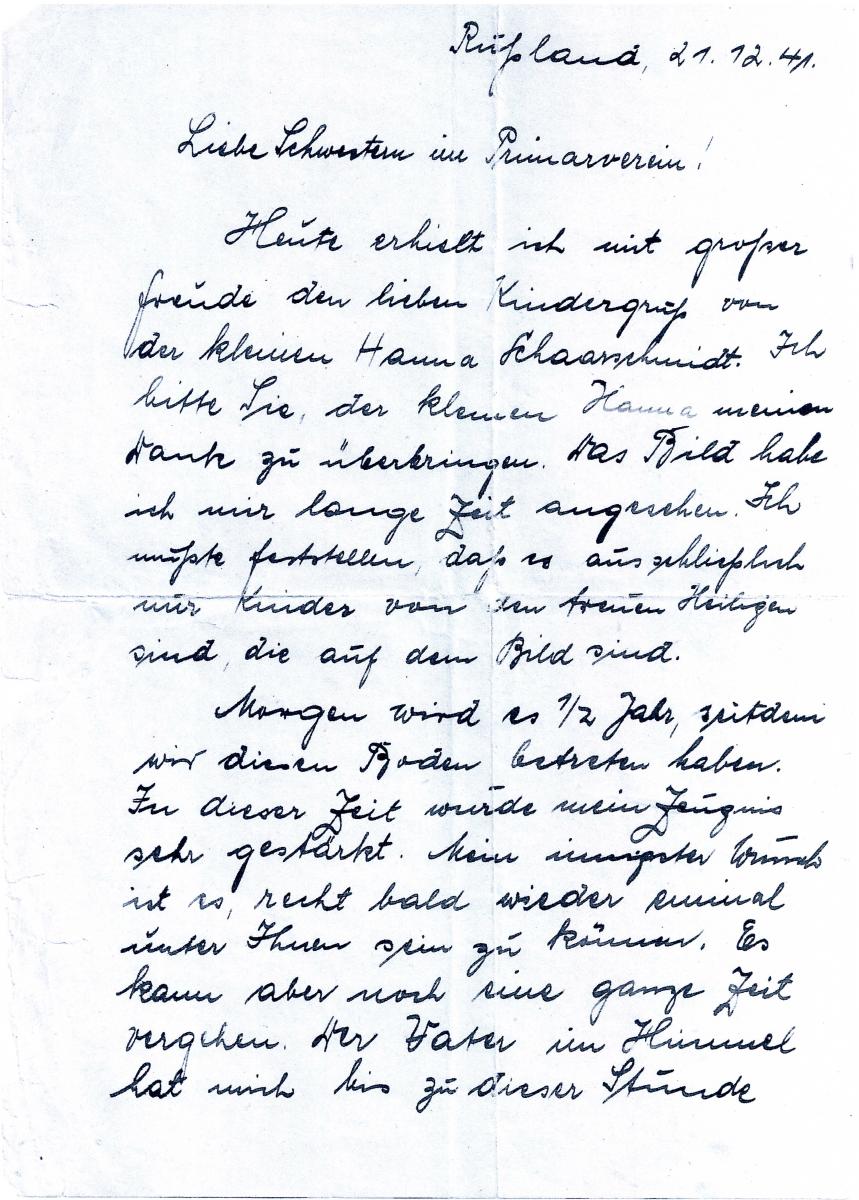

One of the many Latter-day Saints who moved with the Wehrmacht into the Soviet Union in the summer of 1941 was Erhard Wagner’s brother, Kurt, a deacon in the Aaronic Priesthood. In December of that year, he received a photograph of the children of the Annaberg-Buchholz Primary Association. He expressed his gratitude in a letter dated December 21, 1941:

Dear Sisters of the Primary,

Today I received the letter from little Hanna Scharschmidt. Please express to Hanna my deepest appreciation. I have looked at the photograph for a long time. It appears that only the children of faithful Saints are in this picture. Tomorrow it will be one-half year since we entered this country. During this time, my testimony has been strengthened very much. My most fervent wish is to be among you again soon, but that may not be for a long time. My Father in Heaven has guided me through all of this and will continue to do so; of this I am convinced. . . . May you be blessed in your work.[13]

Kurt Wagner wrote to the teachers of the branch Primary in December 1941. (A. Wagner Flade)

Kurt Wagner wrote to the teachers of the branch Primary in December 1941. (A. Wagner Flade)

During a training session in 1941, Erhard Wagner was able to attend church in the Berlin Schöneberg Branch. It was there that he met and eventually fell in love with Marianna Langheinrich, the daughter of the second counselor in the East German Mission leadership. Over the next two years, they were able to spend a few days together and finally were married in his hometown of Geyersdorf in 1943. “The official gave us a copy of Hitler’s book Mein Kampf. We buried it behind my house so the Russians wouldn’t find it [in 1945] and think we were Nazis. It’s still there,” he explained years later.

Erhard Wagner’s unit receiving artillery instruction in Potsdam in 1941 (E. Wagner)

Erhard Wagner’s unit receiving artillery instruction in Potsdam in 1941 (E. Wagner)

Just before Christmas 1941, Erhard was in the Soviet Union, on guard duty at about forty degrees below zero. By the end of his watch, he had contracted such severe frostbite that “blood and water dripped down my chin and right away the skin was gone completely, and raw flesh.” He spent the next nine months in five different hospitals in Latvia and Germany. “I was ready to take my life, believe me, that was so painful when I was wrapped up like a million lice underneath—itching, itching you can’t imagine, and they gave me shots against that itching and then I felt better.” When he finally returned to Russia in late 1942, he was told the sad tale of his unit’s fate:

Two, three days [after I contracted frostbite] the Russian army got some reinforcements, more infantry, more tanks, more guns, more everything, and they broke through our line, we couldn’t hold them. I know when I left that night we were 140 men strong, and eighteen men [were] left [after the engagement], and I wondered, “Would I not be alive today or would I be among those eighteen?” The Lord was really on my side.

Christa Glauche and her father moved from Chemnitz to Annaberg-Buchholz after her mother died in 1942. Christa recounted her impressions of the new branch:

The branch [in Annaberg-Buchholz] was very strong at that time. It was all kept very simple, but in every branch I had been in, there was always a picture of Joseph Smith and Jesus Christ. This branch was larger than the one I had been in before.[14]

Georg Karl Richter (born 1908) had been married since 1932 and certainly did not wish to leave his family to become a soldier. However, the Wehrmacht had different plans, and he was drafted. After basic training in nearby Plauen, he was off to Russia in 1942. A deacon in the Aaronic Priesthood, he took the Bible with him everywhere he went.[15]

At Christmastime in 1942, Georg found himself and his comrades surrounded by Soviet troops. On Christmas Eve, they lit a candle and sang Christmas songs, believing that they could not possibly escape and would soon die. Then they prayed. Shortly thereafter, a German truck came by and they jumped aboard. Somehow the truck made it safely through both the Soviet and German lines. They were shot at but escaped unharmed.

A 1938 priesthood meeting of the Annaberg-Buchholz Branch (H. Martin Scharschmidt)

A 1938 priesthood meeting of the Annaberg-Buchholz Branch (H. Martin Scharschmidt)

In early 1943, the Wagner family of Geyersdorf received heart-breaking news from the Eastern Front. Alice later explained their loss:

I had an older brother, Johannes Kurt Wagner, who was born on October 31, 1920, in Geyersdorf. He went missing in Stalingrad [December 1942–January 1943] while serving for the army in Russia. We received a letter stating that he was missing but never found out if he passed away. My brother was twenty [22] years old at that time, and he was a deacon. He was the secretary of the branch president.

In 1944, Erhard Wagner was sent to France and stationed near Cherbourg in Normandy, just a few miles from the beaches where the Allied forces landed on D-day, June 6, 1944. He was still having trouble with the skin on his face, so he was sent to another hospital some miles from the coast, just a few days before D-day. Again, he escaped combat with the enemy and eventually was stationed near Amsterdam in the Netherlands.

In 1943, Marianna Langheinrich Wagner left her parents’ home in Berlin and moved to Annaberg near her husband’s family. Her first child, Klaus Ulrich, was born there.

One day during the slow German retreat from Russia in 1944, Georg Richter was totally exhausted and simply fell down at the side of the road, unable to continue. When he came to, he found himself on the back of a truck. He later learned that somebody determined that he was still alive, and they loaded him onto the truck. He escaped death by a very slight margin.

Only sixteen years of age in 1944, Wolfgang Scharschmidt was needed by Hitler’s Reich, which by then was facing certain defeat. Wolfgang was trained as an assistant antiaircraft gunner and sent off to western Germany. He explained that near the city of Essen, “the Americans came and I was taken prisoner and was brought to a large camp at Wesel. We didn’t even have a roof over our heads and had to sleep in a field—sometimes we even dug holes so we could be a little safer at night.”

There were few attacks on Annaberg-Buchholz during the war, but quite often the route taken by Allied bombers went close enough that alarms were sounded and people rushed to the shelters. As in most towns, there were few official air-raid shelters, so most people sought refuge in their own basements. According to Ruth Schramm, “Even when they didn’t attack our town, we still had to go down [to the shelter], and sometimes we wouldn’t go down during the day. We watched, oh, how many planes were coming over us!”

The building at Wilischstrasse 10 as it appears today (H. Martin Scharschmidt)

The building at Wilischstrasse 10 as it appears today (H. Martin Scharschmidt)

The resilience of children is remarkable, even in wartime. As Helga Martin recalled, they went about their play. Alarms could be unnerving, but they did not worry much about the possibility of being killed in an air raid:

We lived in an area where there were not many attacks, and we were safer than in other towns. I did not live far from school and when the sirens blared, we were allowed to go home, and I also took other children home with me because their way home was longer than mine. When we played in the forest and we had an alarm, we were scared.

Alice Wagner did not have terrible memories of the air raids but recalled that on at least one occasion, a Church meeting was interrupted so that the members could go to the basement. She saw bombers making their way across the skies to other targets and recalled seeing the red sky over Dresden and Chemnitz when those two cities were bombed and burning in early 1945. After the devastating attack on Chemnitz on March 5, refugees made their way to Annaberg, and the Wagners took in several of them.

As the war dragged on, Helga Martin worried more and more about her father:

The most difficult thing was that my father was not home anymore. He was drafted by the Wehrmacht in 1942. In the beginning, he was close to home, but then they transferred him to a place further away. He was part of the retreat from Greece to Yugoslavia. We did not hear from him in over two years when he was missing. We received the notice in 1947 that he had died on September 15, 1945.

Toward the end of the war, Annaberg-Buchholz was attacked from the air and some damage was done to local structures. Ruth Schramm recalled her feelings at the time:

One thing that I will never forget is our [town] church, our Lutheran church got bombed out, and it was gothic. And it was beautiful, that church. . . . When that was burning, that was absolutely awful. The steeple was one flame. And we stood there—it was early in the morning, three or four o’clock, and then when it finally fell over, we all cried. We really did.

According to Helga Martin, branch meetings were temporarily interrupted in the last few months of the war: “Our branch premises were used as a military hospital, and we could not hold our meetings, and we met at home, and the Methodist church allowed us to use their rooms, so we could at least have our sacrament meeting.”

With the death and destruction visited on Germany, it can come as no surprise that some Saints became discouraged. Ruth Schramm recalled that one of her half sisters was terribly worried about her soldier husband:

She said, “Dad, if he doesn’t come home, I’m going to kill myself.” And she had a four-year-old little girl, and my dad got really angry with her. But one thing she did, every Monday it was fast day for her. She fasted faithfully every Monday that he would come home. So, can you imagine, her faith was really . . . I shouldn’t say shattered, but for a few weeks, she didn’t go to church. But then she went back.

It was later learned that her husband had been killed when strafed by a fighter plane near Sevastopol, Russia.

German soldiers inspect the ruins of a French plane downed by antiaircraft fire. (E. Wagner)

German soldiers inspect the ruins of a French plane downed by antiaircraft fire. (E. Wagner)

For Erhard Wagner, the situation near Amsterdam was calm until April 1945, when Canadian troops attacked their position. By then, Erhard’s unit had no ammunition left; they spiked their guns and simply tried to escape. However, there was nowhere to go; Erhard was wounded slightly and captured by the Canadians.

In their remote location in the Erzgebirge Mountains, the residents of Annaberg-Buchholz did not see enemy soldiers until the war was officially over. According to Ruth Schramm, “There were no [German] troops there, so there was no fighting. The Russians just moved in. I heard the commotion because [the streets were] all cobblestones.”

The defeat of Germany was welcomed by many Germans who thought it meant the end of their sufferings. But some had staked all of their hopes on the success of the country, and the defeat was personally devastating. Christa Glauche recalled the reaction of her brother:

There was one experience which I will never forget. My older brother wanted to be an officer and had already been a noncommissioned officer in charge of a company of soldiers. Just after the war ended, my brother came to Annaberg-Buchholz riding his bike. He carried a bazooka. He did not even know that the war had ended, and he was very surprised and cried bitterly. He remembered the six years that he and his friends had tried to survive this horrible time. I will never forget his crying because as an adult I had never seen him cry. He surrendered himself and was only taken prisoner for a little while by the Americans in [nearby] Schwarzenberg.

When the victorious Soviets came looking for women in Annaberg-Buchholz, Ruth Schramm and the other women in the house often crawled out a back window and hid in a shed. They always managed to elude their pursuers.

Even in the small town of Geyersdorf, the women were not safe from marauding enemy soldiers. Alice Wagner recalled a terrifying experience, in which she believed the hand of the Lord played an unmistakable role:

One night, we were sitting at the dinner table eating our meal when we heard a terrible racket outside. We looked out the window and saw Russian tanks, Russian trucks, Russian motorcycles—Russians everywhere! My father said, “Let’s get on our knees and pray that the Lord will not let anything happen to us.” And he prayed, “Father in Heaven, blind these soldiers that they will not be able to see our house and protect us from the danger that threatens everybody in our neighborhood!” An hour and a half later we heard them coming out of the houses, getting into their vehicles and driving away. The next morning my girlfriend from school asked me if that wasn’t the most horrible night ever. When I told her that they hadn’t come into our house, she couldn’t believe it. She told me that they were in every other house. They had raped her and her mother in front of their family.

Christa Glauche survived what could have been a life-threatening encounter with the occupation forces:

I worked at the telephone central office, and the late shift usually lasted until 11:30 p.m. My co-worker and I walked from Annaberg to Buchholz, and there were some Russians who tried to threaten us. I said that I would tell their commanding officer what they tried if they did not stop. One soldier hit me and the day after, my face looked very different. But nothing else happened to us.

In summing up the behavior of branch members during the final years of the war and the aftermath, Christa stated, “All the members of the Anaberg-Buchholz Branch stayed close to each other during the last hard months of the war. They helped each other in every way.” Eyewitnesses recalled that several Latter-day Saint families arrived as refugees from the East and were taken into already crowded living spaces: the Meier family from Königsberg, the Henkels from Frankfurt an der Oder, and the Births from Schneidemühl.

In September 1945, Erhard Wagner was released by his Canadian captors and made his way home to his wife and son in Annaberg. He could claim to be one of the few German army veterans to march into enemy territory on the first day in all three major German offensives in Europe: Poland, France, and Russia. His wounds were healed, and all he wanted when he got home was to be with his family and to attend church. He had been totally isolated from the Church while at the front, having served continuously from 1938 to 1945. Then, in May 1946, he was called on a mission that lasted until October 1948.

Wolfgang Scharschmidt was released by his captors at the end of 1945. “I was able to go home while others were taken to Belgium or France to work [as involuntary laborers]. But I was not very tall so I was never very valuable to them.” He was all of seventeen years old.

Georg Richter was taken prisoner by the French at the end of the war. After working in coal mines for four years, he was released and returned to his family in Annaberg.

In Memoriam

The following members of the Annaberg-Buchholz Branch did not survive World War II:

Erna—d. from heart failure, 17 Aug 1940 (CHL Microfilm LR 1173 11, 107)

Brigitte Frieda—d. difficult disease 24 Jan 1944 (CHL Microfilm LR 1173 11, 163)

Helmut Otto Goerner b. Zethau, Dresden, Sachsen 13 Nov 1912; son of Karl Julius Goerner and Martha Helene Boerner; bp. 8 Oct 1921; lance corporal; d. Ljubjatowa, southwest of Laura 1 Aug 1944; bur. Pulli, Estonia (IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Alfred Adelbert Hammerle b. Buchholz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 5 Apr 1920; son of Alfred Adelberg Hammerle and Klara Gertrud Nestler; bp. 30 Sep 1933; lance corporal; d. 17 Jun 1944; bur. Orglandes, France (A. Flade; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Richard Hinkel b. Buchholz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 8 Sep 1888; son of Christian Theodor Hinkel and Hulda Grund; m. Buchholz 29 Jul 1922, Johanne Ziegloser; k. in a railroad train under attack by a fighter plane between Wolkenberg and Annaberg, Chemnitz, Sachsen 15 Apr 1945 (A. Wagner Flade; IGI)

Jean Kraemer b. Berlin, Brandenburg, Preussen 7 Mar 1909; son of Johannes Hermann Albert Kraemer and Emma Anna Raabe; bp. 22 Jun 1923; m. Berlin 16 Dec 1937, Auguste Konopatzki; 1 child; d. Mansky, Sachsen, Preussen 11 Mar 1944 (IGI)

Rudolf Johannes Kramer b. Buchholz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 8 Sep 1923; son of Felix Heinrich Kramer and Marthe Friede Mueller; bp. 17 Sep 1931; corporal; k. in battle Sanko, Russia 9 Nov 1943; bur. Sumy, Witebsk, Belarus (IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Rudolf Küler soldier; d. wounds Eastern Front 4 Apr 1942, age 34 (Sonntagsgruss, No. 12, 21 Jun 1942, 47)

Robert Lehrmann d. after a stomach operation 9 Dec 1941 (CHL Microfilm LR 1173 11, 107)

Herbert Karl Lindner b. Annaberg, Chemnitz, Sachsen 17 Dec 1923; son of Karl Rudolf Lindner and Hildegard Louise Groschopf; bp. 17 Dec 1931; d. 26 Nov 1942 (FHL Microfilm 271387, 1935 Census; IGI; AF)

Rudolf Eduard Martin b. Buchholz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 5 Feb 1901; son of August Eduard Martin and Emilie Sidonie Goeckeritz; bp. 10 Apr 1925; m. 29 Apr 1922, Clara Jung; corporal; d. POW camp 46, Bor, Yugoslavia 15 or 16 Sep 1945 (A. Flade; H. Martin Scharschmidt; CHL Microfilm No. 2458, form 42 FP, Pt. 37, 760; IGI; www.volksbund.de)

Bertha Mueller d. old age 19 Jan 1942 (CHL Microfilm LR 1173 11, 107)

Erich Pueschel b. ca. 1918; son of Kajotan Pueschel and Hedwig Krämer; k. in battle (IGI; Glauche-Schlünz)

Kurt Edmund Richter b. Buchholz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 2 Jun 1911; son of Edmund Karl Richter and Frieda Auguste Viertel; bp. 18 Jun 1921; ord. deacon; m. Buchholz 19 Oct 1929; d. Apr 1945 (IGI)

Walter Hans Roscher b. Annaberg, Chemnitz, Sachsen 22 Dec 1919; son of Venzenz Roscher and Marie Bertha Hofmann Schiller; bp. 6 Apr 1928; k. in battle Russia 1945 (A. Wagner Flade; IGI)

Helmut Paul Schaarschmidt b. Geiersdorf, Annaberg, Chemnitz, Sachsen 10 Feb 1913; son of Otto Paul Dostmann and Anna Maria Schaarschmidt; bp. 10 Sep 1926; m.—Bastian; 1 child; d. Dresden, Dresden, Sachsen 17 Feb 1942 (A. Wagner Flade; IGI, AF)

Richard Willy Siebert b. Buchholz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 20 Aug 1908; son of Ernst Richard Siebert and Fanny Olga Auerbach; bp. 16 Apr 1923; ord. deacon; m. 5 Mar 1938; d. 1944 (A. Wagner Flade; IGI)

Paul Richard Teuchert b. Geiersdorf, Chemnitz, Sachsen [R1] 2 Jun 1877; son of August Julius Teuchert and Ernestine Gottlobine Breitfeld; bp. Annaberg-Buchholz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 5 or 15 Jun 1924; m. Geiersdorf 3 Sep 1905, Marie Emma Heinzmann; 2 children; d. stomach cancer Annaberg-Buchholz 30 Apr 1942 (I. Hinkel; D. Henkel Roscher; IGI; AF)

Willy Uhlig b. Reifland, Chemnitz, Sachsen 1 Dec 1905; son of Ernst Albin Uhlig and Hulda Minna Schaarschmidt; bp. 18 Jul 1914; m.; d. Russia 31 Jul 1949 (A. Wagner Flade; IGI, AF)

Johannes Kurt Wagner b. Geiersdorf[R2] , Chemnitz, Sachsen 31 Oct 1920; son of Paul Martin Wagner and Martha Elisabeth Hilbert; bp. 28 Jun 1929; ord. deacon; corporal; MIA Stalingrad, Russia end of 1942 (A. Langheinrich; A. Wagner Flade; FHL Microfilm 245291, 1930/

Herbert Emil Zimmermann b. Buchholz, Chemnitz, Sachsen 16 Aug 1912; son of Karl Emil Zimmermann and Anna Martha Hermann; bp. 20 Sep 1924; ord. deacon; m. Buchholz 14 Oct 1939, Anna Marga Wolf; staff corporal; k. in battle south of Annenieki, Russia 4 Dec 1944; bur. south of Annenieki (A. Wagner Flade; FHL Microfilm 245307, 1930/

Kurt Wagner (J. Flade)

Kurt Wagner (J. Flade)

Notes

[1] Presiding Bishopric, “Financial, Statistical, and Historical Reports of Wards, Stakes, and Missions, 1884–1955,” CR 4 12, 257.

[2] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 31, East German Mission History.

[3] East German Mission Quarterly Reports, 1938, no. 31.

[4] Ibid., no. 35.

[5] Ibid., no. 43.

[6] Ibid., 1939, no. 53.

[7] Ibid., no. 55.

[8] Ruth Schramm Langheinrich, interview by the author, Salt Lake City, December 15, 2006.

[9] Erhard Wagner, interview by the author, Sandy, Utah, April 6, 2007.

[10] Alice Wagner Flade, interview by the author in German, South Jordan, Utah, February 10, 2006. Unless otherwise noted, summarized in English by Judith Sartowski.

[11] Helga Martin Scharschmidt, telephone interview with the author in German, February 15, 2008.

[12] Wolfgang Werner Scharschmidt, telephone interview with the author in German, February 15, 2008.

[13] Kurt Wagner to Primary leaders of Annaberg-Buchholz, letter, December 21, 1941; trans. the author. Used with the kind permission of Alice Wagner Flade.

[14] Christa Glauche Schlünz, interview by the author in German, Rostock, Germany, June 13, 2007.

[15] Georg Karl Richter, telephone interview with Judith Sartowski in German, March 3, 2008.