"There Is No More Satisfying Activity"

D. Arthur Haycock's Lifetime of Missionary Labors

Brett D. Dowdle

Brett D. Dowdle, "'There Is No More Satisfying Activity': D. Arthur Haycock's Lifetime of Missionary Labors," in Go Ye into All the World: The Growth and Development of Mormon Missionary Work, ed. Reid L. Neilson and Fred E. Woods (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center, 2012), 365–96.

Brett D. Dowdle was a PhD student in American history at Texas Christian University when this article was published.

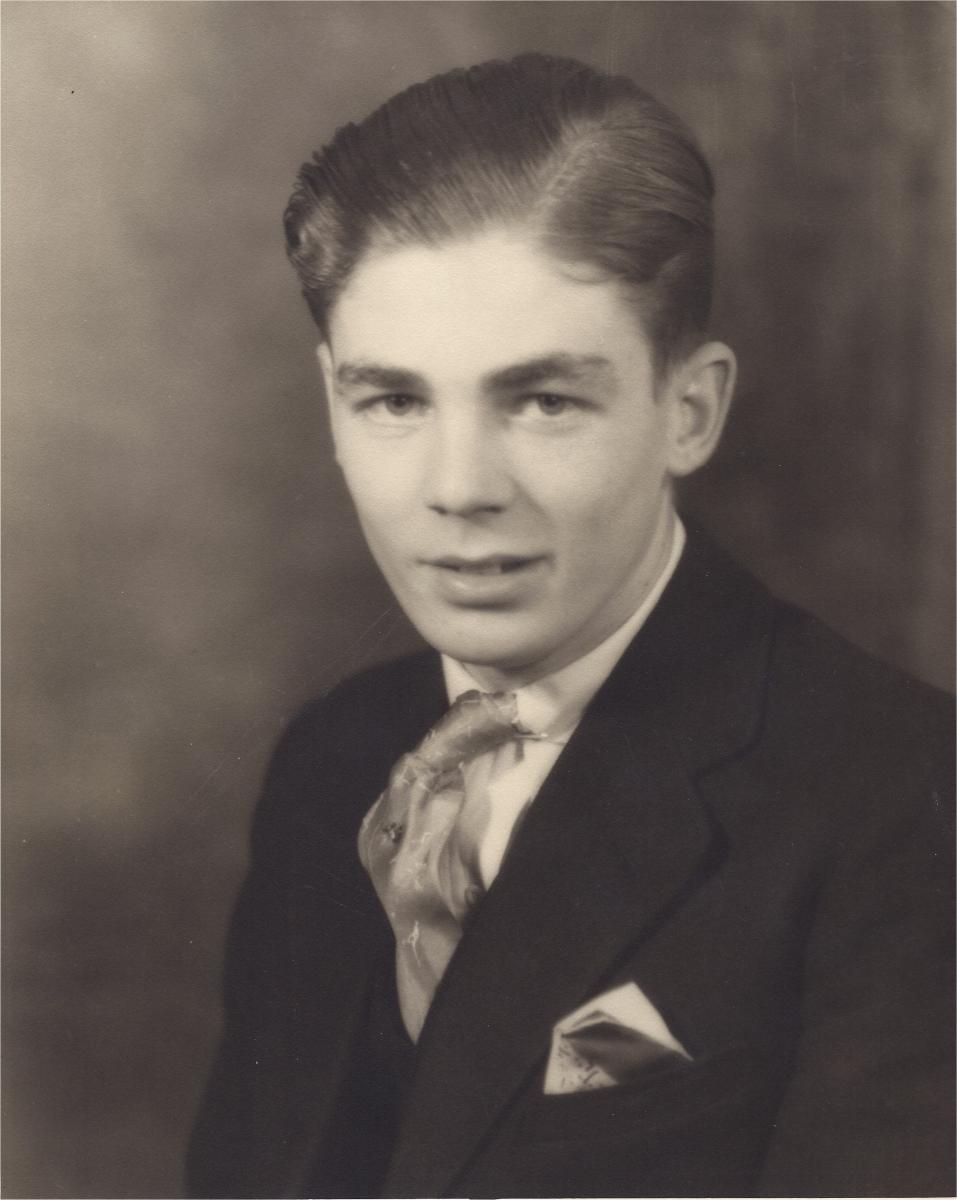

Elder D. Arthur Haycock, 1935, prior to leaving for Hawaii. All images in this chapter are courtesy of Lynette H. Dowdle.

Elder D. Arthur Haycock, 1935, prior to leaving for Hawaii. All images in this chapter are courtesy of Lynette H. Dowdle.

On February 25, 1994, David Arthur Haycock died in Salt Lake City at the age of seventy-seven. [1] Throughout his lifetime, Arthur became acquainted with nearly every facet of and experience afforded by the missionary program operated by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. During these years, Arthur served as a missionary, as a mission president, and as the secretary of the Executive Missionary Committee. In addition, as a member of a devout Mormon family and as personal secretary to five Presidents of the Church, he experienced a variety of other missionary-related experiences. Beyond gaining a general appreciation for those who carried out the proselytizing work of the Church, Arthur witnessed a profound transformation in the Church’s missionary labors in the twentieth century. During his various missionary experiences, Arthur recorded the metamorphosis of missionary work, culminating in the development of the contemporary missionary program of the Church. Although many procedural aspects of the Mormon missionary program dramatically changed between 1916 and 1994, Arthur’s experience also reveals a deep sense of continuity in the underlying principles of missionary work.

Son of a Missionary Father

As Church members, when we discuss missionary work, we often justifiably focus primarily on proselyting efforts and the resultant baptisms, conversions, and even rejections. The history of missionary work, however, is likewise the story of the home front and the influence that missionary work has upon the parents, wives, and children who remained behind. Missionary work is thus a familial enterprise, affecting far more than the elders, sisters, and couples who are issued a formal call to serve. While those who remained behind may not have engaged in the day-to-day labors of contacting investigators and preaching the gospel, theirs is an integral part of the narrative of missionary labors.

In 1922, when Arthur was five and a half years old, his father, David, was called to leave his wife, Lily, and their three children to serve as a full-time missionary in the Northern States Mission. David Haycock’s mission came at a profound sacrifice for the young family. Lily was left to support both the costs of her husband’s missionary labors and the family’s three small children, all during a period of significant financial turmoil and economic depression in Utah and the Intermountain West. [2] To survive financially, Lily and the children moved to Herriman, Utah, where they could be close to her family. After a short time in Herriman, Lily and the children were forced to move to the edge of town when their landlord “decided to move into part of the house” and raise the family’s rent. [3]

During David’s mission, Lily took over full responsibility for the care of the Haycock family. In addition to caring for the ordinary temporal needs of the family, Lily had to perform other difficult tasks, like killing a snake that had come into the house, in spite of her fear of snakes. Furthermore, she was left alone to deal with challenges that included two near-death accidents that threatened the lives of her two sons, Arthur and Gordon. [4]

David Haycock, Arthur's father, ca. 1920, when he was called to serve in the Northern States Mission.

David Haycock, Arthur's father, ca. 1920, when he was called to serve in the Northern States Mission.

The whole family learned vital lessons about the financial sacrifices of missionary work. David’s absence necessitated the efforts of every family member to meet the Haycock family’s temporal needs. During David’s mission, Arthur became Lily’s “chief helper and worked like a little man, helping with the washing, working in the yard and helping tend the younger children.” [5] These years taught Arthur the value of food. On one occasion, when he tried to dispense with some unwanted eggs in the family’s ash pile, Lily made him pick the eggs out of the pile and finish eating them. [6] On another occasion, Arthur stopped on the way home from the grocery store to eat a loaf of bread, betraying his own hunger and the scarcity of food in the Haycock home. [7]

Although they were surrounded by family in Herriman, the family “spent many, many lonely days and nights” while they waited for David to return from his missionary labors. [8] In one instance, the family sat on their porch and watched as “nearly everyone in town went away” to celebrate the Fourth of July, wholly conscious of the fact that due to their financial circumstances they “had no way to go anywhere.” In David’s absence, Lily often became frustrated because neighbors and friends treated the children “like they were orphans,” taking it upon themselves to discipline them for their rambunctious behavior. [9] According to Lily, many in Herriman “seemed determined [that] Arthur [in particular] was never going to grow up.” [10]

After nearly two years of familial sacrifice and struggle, David Haycock’s mission was cut a few weeks short when news came that his father had died following an accident. David was released to return home a few weeks early to attend the funeral. Despite the sadness of the circumstances that caused David’s early return, Lily wrote that the family was “overjoyed and excited” to have him home. [11]

In spite of the many challenges that David’s missionary service presented to his young family, it also produced several blessings. When upon two different occasions the lives of Arthur and his brother Gordon were threatened by serious accidents, these men’s lives were miraculously preserved. [12] Furthermore, David’s absence fortified the resiliency, strength, and faith of the entire Haycock family. This faith would play a crucial role in the commitment and devotion in the lives of David’s children, including Arthur. Whereas recent generations learn about missionary work by singing Primary songs like “I Hope They Call Me on a Mission,” participating in seminary “missionary weeks,” and watching older siblings serve missions, Arthur and many others from his generation learned about missionary service by watching their mothers struggle to support the family while their fathers were called to serve. In later years, when a variety of missionary calls came to Arthur, he responded with the faith and devotion that he had witnessed in his parents in earlier days. Due to his father’s missionary service, Arthur learned early that missionary work always came at a sacrifice but likewise yielded great blessings.

Although signs abounded that the world in general and the Church in particular were entering a new era of modernity during the early 1920s, David Haycock’s missionary call hearkened back to the nineteenth-century model of Mormon missionary work, in which more experienced priesthood holders generally bore the burden of the Church’s evangelical labors. [13] In coming years, the burdens of missionary work would be increasingly shifted from the shoulders of young married men to the less-burdened shoulders of single young men in their late teens and early twenties.

Training Experiences

Arthur’s adolescent years produced several opportunities for growth and preparation for missionary service. While a student at South Junior High School in Salt Lake City, he was an active participant in South High’s seminary program. Seminary allowed Arthur to receive training in the gospel and the scriptures and brought him under the tutelage of Harold B. Lee, then president of the Liberty Stake and part-time seminary teacher. President Lee and Arthur developed a close relationship during this class. Throughout the rest of his life, President Lee referred to Arthur as “one of his boys.” [14] In later years, when Arthur served as a mission president and secretary to the Executive Missionary Committee, President Lee continued to mentor Arthur, providing him with valuable counsel on a variety of missionary-related matters. [15] The seminary likewise allowed Arthur to become acquainted with Maurine McClellan, his sweetheart and future wife, who was an active partner in Arthur’s missionary service throughout his life. [16]

Arthur graduated from South High School in 1933, during the middle of the Great Depression. He became a beneficiary of Roosevelt’s New Deal and obtained work with the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) in Salt Lake City. Although he was not old enough to work in the CCC camps, Arthur’s skills in bookkeeping and office work allowed him to obtain a position “at the warehouse writing orders for supplies and food and equipment for the 25 to 30 camps in the western United States that were supplied by a convoy from [the Salt Lake] warehouse.” [17] The opportunity to work in the CCC enabled Arthur to have his first major experience in coming into contact with young men from different parts of the nation. The vast majority of those he associated with in the CCC were not Latter-day Saints, which allowed him to form his first close relationships with members of the non-Mormon community. Speaking of this at Arthur’s funeral, President Gordon B. Hinckley stated, “Most of those in that group were tough hard kids, some of them from the ghettos of the big cities of the nation. He learned to get along with them without giving in to the way they talked or the way they acted or the things that occupied their minds.” [18] This experience allowed Arthur to learn that missionary work was not always a matter of formal proselyting but often included forming relationships with and providing examples for friends outside the Church.

First Mission to Hawaii

After working for the CCC for a little over a year, Arthur was called to serve a mission to Hawaii. He was only eighteen at the time of the call, but by his own account, “they weren’t as fussy about ages in those days as they are now.” [19] Without a missionary training center, Elder Haycock left immediately for Hawaii after spending a couple of days at Church headquarters. The night before he left for Hawaii, he gave a ring to his sweetheart, Maurine, solidifying their commitment to each other. [20] Because he was single throughout his missionary service, Arthur’s mission had far less of an impact upon Maurine than his father’s mission had upon Lily and the Haycock children during the 1920s. In a matter of only a few short years, the demographics of missionary work had begun to shift toward single young elders. While there was at least one married elder in Hawaii during the period of Arthur’s service, that elder’s wife had likewise been called to serve in that same mission, suggesting a Church effort to minimize the impact of missionary labors upon young couples. [21]

Upon arriving in Honolulu, Elder Haycock was assigned to spend his first day tracting with another missionary. The experience, however, proved to be far from ideal and introduced him to some of the unfortunate realities of missionary work. Arthur later described this experience:

We left the mission home about nine o’clock in the morning and took the streetcar toward Waikiki and Kaimuki as far as the streetcar would go and then got off and walked up the side of the hill into the tall grass. I wondered how we were going to do any tracting there, because there were no houses anywhere around. [My companion] laid down in the grass and went to sleep and left me standing there. Finally I sat down and then began to read the Bible, which I had with me, to salve my conscience. This was not my idea of missionary work and what I had come to do. . . . This is where I spent the day, and finally I dozed off too. At last, around 4 o’clock, [my companion] got up brushed himself off and stretched and said, “Well, we’ll have to hurry if we [want to] get back to the mission home in time for supper.” [22]

Although difficult, this day proved crucial to Arthur’s later missionary experiences. Relating that he had “always felt cheated about the first day in the mission field,” he determined that “a new missionary deserved a good companion . . . who teaches him to respect and honor the calling and to make out the reports accurately, fairly, and honestly.” He noted that in later years he “used this example hundreds and hundreds of times” as he spoke to “missionaries in Hawaii and around the world.” [23]

Shortly after Arthur’s arrival in Hawaii, Presidents Heber J. Grant and J. Reuben Clark Jr. arrived to organize the Oahu Stake, the first stake outside of the continental United States. [24] In terms of Church wide significance, the creation of this stake demonstrated the continued expansion of the Church beyond the borders of the Great Basin and the Intermountain West’s Mormon Corridor.

While the creation of this stake was an event of historic proportions on a Church wide level, it also held deep personal meaning for Arthur and played a profound role in shaping the remainder of his life. During the visit, he watched Joseph Anderson, President Grant’s secretary, and “made up [his] mind that that was the kind of job that [he] would like to have,” though due to his “lack of education and contacts,” that hope seemed to be nothing more than “a dream.” [25] Learning of Elder Haycock’s desire, Brother Anderson encouraged the young elder to “come and see him” upon returning from his mission. [26] Soon after returning from Hawaii, Arthur took this counsel seriously, applying for a position at Church headquarters “every Monday at noon” for a year until he finally received a position in the Church’s Finance Department. [27]

In addition to providing Arthur with a career goal, Arthur’s missionary experience brought him into contact with both the positive and negative realities of life. Little more than six months into his mission, Elder Haycock received the difficult news that his baby brother, Lawrence, had died of a ruptured appendix. [28] Not wanting him to learn of the death by way of letter, his parents wrote to his mission president and asked him to inform their son of the tragic circumstances. The news came as a hard blow to Arthur, who had frequently written of his love for and desire to see Larry. [29] Although Arthur remained in the field, the pain of Larry’s death was sharp, and when Arthur saw a picture of Larry upon his return home, he responded solemnly, “I am glad I wasn’t here, I couldn’t have handled it.” [30]

In addition to the trying conditions at home, the mission field itself presented numerous challenges. During these years, Hawaii had not yet become the tourist paradise that would attract millions of visitors later in the century. In spite of the temperate climate and beautiful scenery, at this point, the islands remained something of a remote destination with what most Americans would have described as primitive living conditions. While serving in Kona, Elder Haycock lived “out in the jungle in a little one-room shanty on the side of the chapel.” The house’s shower and bathroom facilities were “outside behind the chapel with nothing to protect [the elders] from prying eyes,” with the only water coming from “what ran off the roof of the chapel into an open wooden tank.” Without a proper cover, this water tank was often a haven for birds, mice, and rats, which led the elders to boil all their water. The house offered no amenities and was “full of rats” that would “run across the floor at night and jump over [the elders’] beds.” Due to these conditions, Arthur’s companion contracted typhoid fever and was sent home early to recuperate. [31]

Whereas Larry’s death and the primitive living conditions taught Arthur that missionary work occasionally taxed the emotions, strength, and endurance of missionaries, other experiences taught him of the profound joys to be found in the work. He witnessed firsthand the devotion of local members and their love for the missionaries. On one occasion Elder Haycock and his companion set out from their residence in Kona “for a thirty-five mile trek . . . to perform a marriage.” They had planned to stay at the home of the branch president but learned on the journey that his wife had just given birth to a new baby. Not wanting to impose, the elders “decided to stay with a Hawaiian sister whose meager resources forced her to live on sour poi and cold rice.” While walking toward their destination, the elders were caught in a large storm with no shelter. “To keep up their spirits, they mused about their favorite foods, what they would eat . . . if they could choose the perfect meal,” settling on “thick slices of bacon with fresh eggs fried in the grease.” Knowing that the elders were out in the storm, the branch president set out in his truck, eventually finding them “cold and weary, and took them to his home.” As the two elders showered and changed clothes, the branch president prepared a dinner of fried pork and fresh eggs. From this experience, Arthur concluded, “‘The Lord looks after his servants if they will do their part.’” [32]

Mother's Day in Honolulu with President Castle H. Murphy, May 12, 1935. Arthur Haycock is second from the right.

Mother's Day in Honolulu with President Castle H. Murphy, May 12, 1935. Arthur Haycock is second from the right.

Despite his mission’s challenges, Arthur fell in love with Hawaii. He later confided in a friend that Hawaii had gotten “in [his] blood,” a feeling that remained with him throughout the rest of his life. [33] His letters to his sweetheart, Maurine, throughout his mission indicated a desire to one day return to the islands with her, perhaps even in a missionary capacity. He boldly wrote to Maurine, “I would be thrilled if some day I could sign [letters] President, Hawaiian Mission,” not suspecting that less than two decades later he would be called to that very position. [34] Thus Arthur had found a home in Hawaii, which was difficult to leave behind and which left him somewhat “uncomfortable away from the islands.” [35]

Home, War, and the Home Front

Upon returning home, Arthur married his sweetheart, Maurine, and secured a coveted position with the Church Finance Department. At the time, the temporal affairs of the Church were managed by a skeleton crew of employees working under the direction of Church leadership. The small number of Church employees was a reminder of the fact that the Church had been affected by nearly sixty years of economic struggles and had lately endured the consequences of two decades of severe depression. These circumstances, however, allowed Arthur to begin to see the inner workings of the Church at close proximity and kept him in close personal contact with the missionary program in spite of the fact that he worked for the finance department. This in turn helped Arthur to see missionary work as part of a worldwide effort that extended well beyond the Hawaiian Islands and which was influenced by the shifting tides of world events.

During his first months working for the Church, Arthur’s duties involved sending funds to missionaries throughout the world. When parents brought money for their missionaries into the office, Arthur worked to convert the money into the appropriate currency and then sent checks to the various mission presidents for distribution to the specified missionaries. [36] Accordingly, this experience deepened Arthur’s understanding of the costs of missionary service and of the sacrifices made by families to support those missionaries.

Arthur’s responsibilities with the missionary program changed dramatically, however, on September 1, 1939, when Germany invaded Poland, prompting England to declare war. Based upon their experience with World War I, Church leaders had hoped that merely transferring the elders to Scandinavia would protect the missionaries from danger and allow them to finish the remainder of their missionary service. Scandinavia, however, was likewise overrun by war, leading to a rush to get the “missionaries home on freighters and everything else . . . through torpedo infested waters.” Miraculously, none of the boats transporting missionaries were sunk, and the majority of the elders were able to continue their missions in the Eastern States Mission. [37] Following this initial miracle, however, the war took a heavy toll on the missionary force of the Church, resulting in the almost complete cessation of the formal missionary program and the further curtailing of the Church office staff. Even staff members like Arthur and Gordon B. Hinckley who were declared unfit for military service were encouraged by Church officials to leave their employment at the Church to “do something more . . . to contribute to the war effort.” [38] Accordingly, with some sense of apprehension that his job with the Church might not still be there after the war, Arthur left his position at the Church offices and began working at the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad Depot in Salt Lake City. Gordon B. Hinckley likewise took a position with the Denver–Rio Grande when he was declared physically unfit for military service. Hinckley worked as the station manager while Arthur “worked in the shops slinging the sledge hammer and repairing the steam engines.” On Hinckley’s recommendation, Arthur was hired as the new station manager when Hinckley was transferred to Denver. [39]

Arthur’s first few years working at the Church offices did little to suggest that he was working for an organization that was poised for massive worldwide expansion. The relatively small number of employees and the Church’s meager budget, combined with the increasing troubles of a worldwide war, did little to instill confidence in the immediate future of worldwide expansion. In spite of such circumstances, however, there were some signs in the late ’30s and early ’40s that the Church was positioning itself for major growth. During this period, Arthur became closely acquainted with Gordon B. Hinckley, a fellow employee who was spearheading a major project to revamp the Church’s publicity efforts. Ultimately, this effort would result in the development of powerful new channels for spreading the Church’s message to interested parties. [40]

Postwar Employment and a Call to Return to Hawaii

Following the war, Arthur accepted an offer from Richard L. Evans to return to the Church as the office manager for the Improvement Era. In 1947, two events happened that brought Arthur back into close contact with the missionary program. First, he was called to be the bishop of the newly organized Riverview Ward in the Pioneer Stake, in which capacity he corresponded with the ward’s missionaries. Second, in July 1947, he was named personal secretary to President George Albert Smith, a position that, although not directly linked with the missionary program, heavily influenced his later missionary activities. [41]

As President Smith’s secretary, Arthur was able to travel to a number of different locations throughout the United States and to become acquainted with several prominent dignitaries, including President Harry S. Truman. [42] From 1947 until his death in 1951, President Smith provided Arthur with valuable training in interfaith relations. This was the case particularly with the Reorganized Church, a relationship which President Smith spent a great deal of time seeking to repair. Arthur relates that some questioned why President Smith spent so much time with the Reorganized Church. President Smith characteristically responded, “They are my kinfolk. . . . I’m an old man, and in the normal course of events, I will soon go to the other side. When I do, if my kinsman, the Prophet Joseph, isn’t there to meet me, I’m going to look him up. After we’ve embraced, I’ll stand back and say, ‘Brother Joseph, I want you to know that while I was on the other side, I did everything in my power to bring your own flesh and blood into the church for which you gave your life.’ I don’t want to have to hang my head.” [43] In this effort, President Smith kept in close contact with President Israel Smith of the Reorganized Church. Israel later attended George Albert Smith’s funeral, describing him as “a great man.” [44]

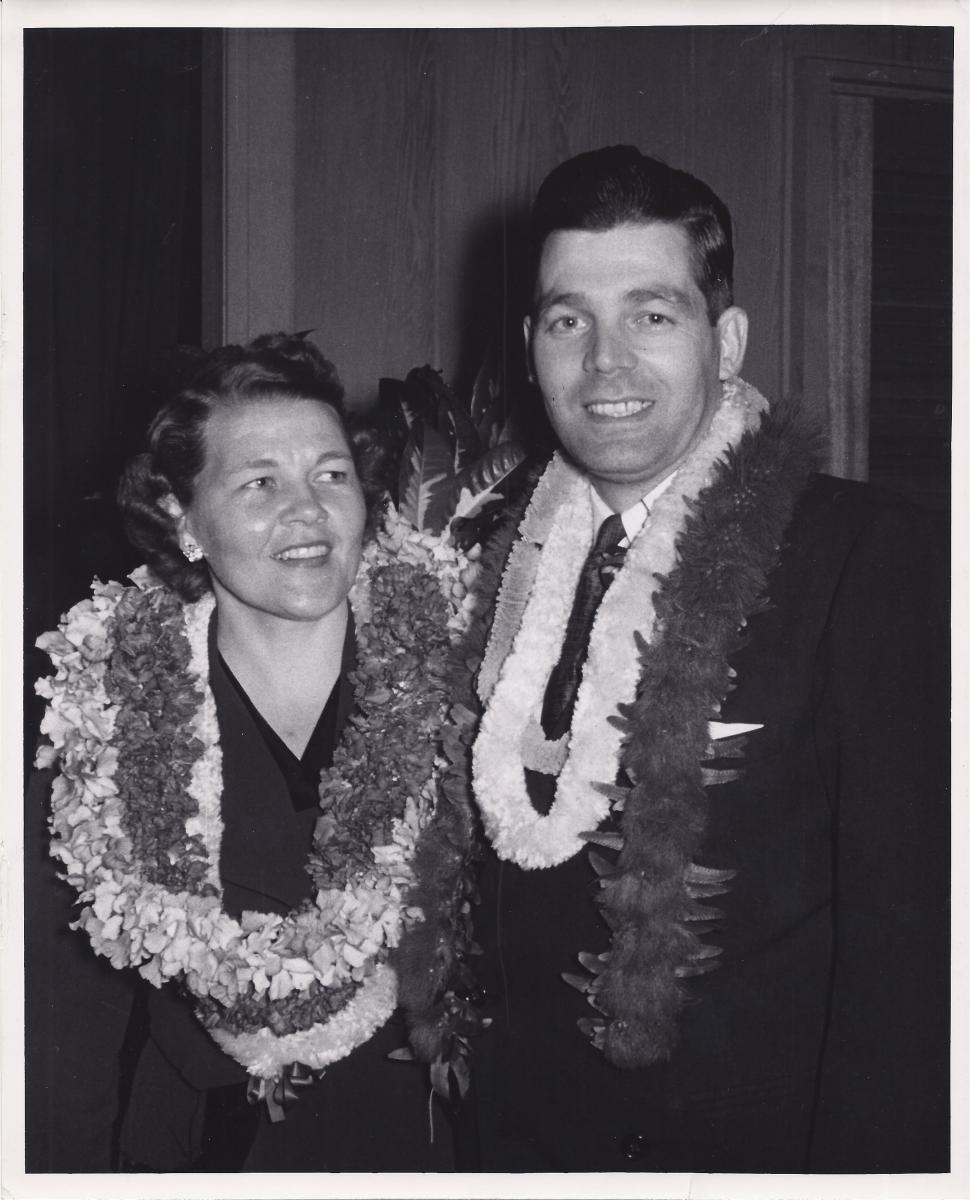

D. Arthur and Maurine M. Haycock at a White House ball in 1954.

D. Arthur and Maurine M. Haycock at a White House ball in 1954.

Arthur’s ability to work with those of other faiths took on even greater importance during the 1950s, when he was asked to move to Washington, DC, to work as an administrative assistant to Elder Ezra Taft Benson in the Department of Agriculture. This position placed Arthur and his family in a new and occasionally uncomfortable environment, but it also provided them with numerous opportunities to develop friends outside of the Church. Although Secretary Benson’s staff included several Latter-day Saints, the majority of the staff members belonged to other faiths. Arthur developed many close relationships with these staff members. Many of these coworkers expressed regret and asked him to “send us a card or two and let us know how you are getting along” when Arthur left Washington to return to Hawaii. [45] These friendships brought Arthur a variety of missionary opportunities in later years, including the opportunity to show J. Earl Coke, the assistant secretary of agriculture, around the mission home in Hawaii in 1954. [46]

Concurrent with Arthur’s service in Washington, his parents were called to serve as missionaries in the Northern States Mission, “with a special assignment to Nauvoo.” [47] Together with Elder and Sister Wilford Wood, Elder and Sister Oscar Wood, and Elder and Sister Paul L. Newmyer, David and Lily helped to create one of the Church’s first historic sites missions. Although much of their assignment consisted of providing tours to visiting Mormons, the use of locations such as Nauvoo for missionary purposes provided evidence for the fact that President McKay had “ushered in a ‘New Era’ of missionary work” that would be defined by bold new methods in sharing the gospel. [48]

Among President McKay’s bold initiatives to increase the efficacy of the missionary program was a change in “the demographic profile of the mission presidents.” Rather than calling older presidents, the First Presidency asked for “younger men out there, vigorous, that know how to motivate people and get this missionary work going.” [49] In February of 1954, at the age of thirty-seven, Arthur was called to be a member of this younger generation of mission presidents.

Although the call came at a significant financial sacrifice, it provided a welcomed change of venue for the family. While Arthur had found the work in Washington “exciting and interesting” and full of cultural and financial advantages, he disliked the Washington environment. [50] Thus, when President Stephen L. Richards extended the call to preside over the Hawaiian Mission, Arthur immediately and enthusiastically responded, “We’ll go.” Before accepting Arthur’s answer, President Richards responded that Arthur “had better talk to [Maurine] and to Brother Benson.” To this Arthur said, “I’ll talk to them, but the answer will still be the same.” After he had received the approval of his family and Secretary Benson, Arthur called President Richards to officially accept the calling to return to his second home, where he was finally able to sign letters “President, Hawaiian Mission.” [51] The Haycocks decided to take their four daughters with them.

As news of the call was published, commendations on the calling poured in from a variety of individuals. [52] Although Arthur had enthusiastically accepted the calling, his acknowledgement of such commendations was more subdued and reflected significant maturation in the years since he had secretly wished to be president of the Hawaii Mission. Likely not remembering his letter written as a young elder, or at least not having been proud of it, Arthur somewhat ironically wrote to a former ward member, “Our call came as a great surprise. Nothing was ever farther from my mind. I have always wanted to go back to Hawaii but, naturally, never ever supposed under such circumstances.” [53] To another friend, he wrote, “As you can readily appreciate, this call came to me as a great surprise, not to mention as a shock. Nothing has ever been further from my mind because I have just never considered myself to be Mission President material. . . . I am frightened as I contemplate the responsibility of such an assignment.” [54]

Acknowledging the weight of his calling, Arthur began preparing for his return to Hawaii. In April 1954, he was invited to come to Salt Lake City to attend general conference and “a three day session of meetings with the Mission Presidents.” Something of a precursor to the Seminar for New Mission Presidents, this experience provided the new mission president with “some much needed instruction and counsel” as well as a greater sense of encouragement and enthusiasm for the work. [55] Additionally he wrote to Ernest Nelson, the current mission president, asking for “the latest facts and figures on the mission” and for information concerning the mission’s proselyting plans and use of foreign languages. This letter also indicated that he was preparing to implement some new ideas—visual aids such as flannel board[s] [and] film strips” based upon what he had learned during the training session in Salt Lake City. [56]

After selling the family’s house in Virginia at a substantial loss, the Haycocks returned to Utah long enough for a short farewell program to be hosted by the Riverview Ward and for Arthur to be set apart by his friend and mentor President J. Reuben Clark Jr. [57] Immediately after the farewell, the Haycocks traveled to Los Angeles, where they boarded the S. S. Lurline for Honolulu, arriving in Hawaii on June 21, 1954. [58] Less than a week after his arrival, President Haycock had visited with missionaries and members on the islands of Oahu, Kauai, Maui, and Hawaii. [59]

Mission President in an Era of Expansion

While many of the members and locations were the same as when he had been a young missionary, the Hawaii Honolulu Mission was remarkably different from what it had been in the 1930s. When Arthur finished his mission in 1937, there had been a total of 32 missionaries and 87 convert baptisms for that year. [60] By the 1950s, the number of missionaries had grown to over 100, with close to 150 baptisms per year. [61] The demographics of the mission reflected the Church’s continued move toward a younger and increasingly single missionary force, as the majority of the missionaries were young single elders and sisters, with a few young married couples and a few senior missionaries intermingled. [62] In addition, there were at least two married elders whose spouses were not serving with them. [63] Along with the increased numbers of missionaries, the mission saw an increase in baptisms. At the end of Arthur’s term as mission president, the Deseret News reported, “Baptisms . . . increased from less than two per missionary to nearly seven in less than four years’ period.” [64]

Though several factors likely influenced this increase, historian R. Lanier Britsch has attributed the growth to the “improved teaching methods” implemented during these years. [65] One of President Haycock’s first initiatives as mission president was to call two elders to serve as “Special Representatives of the Mission Presidency.” These elders were charged with the assignment to travel throughout the mission and give the missionaries “assistance in proselyting methods” as well as “to glean from the missionaries ideas of value to be shared with the other missionaries.” [66] They trained the elders in the use of visual aids and reported that they “found the missionaries . . . only too anxious to accept the suggestions on the new visual aid plan which we have given them.” [67] Also, beginning in 1954, the Hawaii Mission implemented a new program for training its missionaries. During the unproductive two weeks surrounding the Christmas holiday, the missionaries on Oahu attended a course taught by a member of the mission presidency in which they “stud[ied] scriptures, present[ed] lessons on the new [proselyting] plan, receive[d] instructions, and [made] visual aids.” [68] The results of these courses proved to be “very beneficial.” [69] Because of the success of these classes, the mission began holding similar classes for each of the new missionaries who came to Hawaii. [70] It was clear to President Haycock that one of the keys to missionary success was to provide the missionaries with more effective training prior to their entrance into the mission field.

President and Sister Haycock while presiding over the Hawaii Mission, ca. 1955.

President and Sister Haycock while presiding over the Hawaii Mission, ca. 1955.

While the majority of this training would emphasize proselyting methods and the spiritual aspects of missionary labors, the Hawaii Mission also provided the missionaries with adequate cultural preparation. Cultural instruction was a regular part of the missionary meetings, thus allowing the missionaries to better understand the people they were teaching. [71] Along with instruction in the Hawaiian culture, the missionaries were also encouraged to study and become conversant in the Hawaiian language. [72] During his 1955 visit to the islands, President David O. McKay had encouraged the missionaries to “study and learn the Hawaiian language . . . even though it is not used too extensively in most areas of the mission.” He promised the elders that it would “be to our good and advantage and the blessing of the people and the Church” if they would study the language. [73] While it is doubtful that the missionaries ever made extensive use of their language skills, the study of Hawaiian language and culture allowed them to better understand their investigators and present the message in a way that would reach them.

Mission presidency with local leaders, ca. 1957. Photo shows Arthur with local Hawaiin leaders after deciding to release the missionaries from leadership positions.

Mission presidency with local leaders, ca. 1957. Photo shows Arthur with local Hawaiin leaders after deciding to release the missionaries from leadership positions.

Along these lines, President Haycock pushed for the development and elevation of local Hawaiians to positions of ecclesiastical responsibility that had traditionally been held by missionaries. President Haycock worried that these positions prevented the elders from performing the proselyting work that they had been called to do. Elders called to leadership positions often traveled “up and down the island[s]” in administrative rather than missionary capacities. He further worried about the level of responsibility that such callings placed upon young elders, who were called to interview the Saints for “temple recommends, priesthood advancement, branch president positions and so on,” often without knowing “the first thing about interviewing.” Additionally, calling young missionaries as district presidents placed a significant burden on the members, many of whom were qualified to hold those same positions. Arthur later described one elder whose two counselors were “two local brethren [who were] old enough to be his grandfathers” and who had “forgotten more . . . about the Church” than that young elder had ever known about it. Although the missionaries were inexperienced, the local members loyally supported and sustained the elders called to lead them. [74]

Noting this burden on the members, President Haycock determined that the best course to follow was to release the missionaries from leadership positions, replacing them with qualified local brethren. [75] In a conversation with Elder Marion G. Romney, he asked, “What would happen if I released all the missionaries doing these jobs and sent them back to knocking on doors[?]” Elder Romney responded, “Why don’t you try it. They can’t excommunicate you for trying.” With Elder Romney’s approval, Arthur immediately “released all the elders” and replaced them with “all local brethren.” [76] The maneuver gave the Church in Hawaii a “new impetus and added interest” as the Saints felt “the responsibility of leadership.” [77] Not long afterward, stakes were formed throughout the islands that were led by many of these same members. Even local newspapers praised the decision and wrote stories with titles like “Mormon Church Elevates Local Members.” [78] Arthur even hoped that in time native Hawaiians would fill the positions of mission and temple president. [79]

After four years of missionary service and considerable success, President Harry S. Brooks was called to replace President Haycock as the president of the Hawaii Mission. As with all missionary work, his service in the position had come at a sacrifice for both himself and his family. While serving with Arthur, Maurine had missed the death and funeral of her mother. [80] Although she had taken a short trip home to be with her mother, she had returned to Hawaii just weeks before her mother’s death, feeling “that she could not remain away longer from her mission responsibilities.” [81] Describing her demeanor during this ordeal, Arthur wrote in his diary, “Maurine is a real soldier, feels bad that we can’t be present [at the funeral] but holding up very well. I am proud of her.” [82] The mission taxed the family financially, too. Far from financially independent at the time of his call, the six members of the Haycock family had lived on a meager allowance of $225 a month throughout the mission. In Arthur’s words, the family “came home literally with the clothes on our backs,” for a time boarding with his parents. [83] Adding to the strain was the fact that Arthur was uncertain about his future employment, although he had received a number of job offers. On the advice and recommendation of Elder Mark E. Petersen, he eventually accepted a position with the Deseret News.

Despite such challenges, Arthur noted, “We struggled for a long time, but we have never been sorry. We never regretted it, and I am grateful for the privilege of being with those people and serving the hundreds of missionaries who came under our watchful care.” [84] He frequently described the blessings of missionary work, writing to one friend, “We certainly find plenty to keep us busy night and day but as you can readily appreciate, there is no more satisfying activity in all the world than to be sharing the Gospel with our Father’s . . . children.” The mission was a great blessing to the family, providing them with close friendships and associations that would bless the Haycocks for the remainder of their lives. While the family members felt blessed by their associations with all the Saints, they felt particularly blessed as they witnessed “the faith and unselfish devotion of the young missionaries,” saying that it was “enough to stir the emotions and strengthen the testimony of anyone who sees them in action.” [85] For the remainder of their lives, Arthur and Maurine maintained close personal relationships with their missionaries, many of whom “spoke about Arthur [and Maurine] . . . with reverence.” [86] At the end of his life, Arthur proudly noted that two of his missionaries were mission presidents and others were serving as stake presidents. [87]

Missionary Executive Committee and Secretary to Prophets

For the remainder of his life, Arthur continued to be involved in missionary work to one degree or another. In 1963, Arthur was one of twenty-nine men appointed to be members of a newly formed Priesthood Missionary Committee. Serving under the direction of President Joseph Fielding Smith, the committee members were assigned to “assist the General Authorities in conducting stake quarterly conferences as representatives of the Missionary Program of the Church.” [88] In December of that same year, Elder Spencer W. Kimball invited Arthur to become the secretary to the Church’s Missionary Committee. [89] Elders Kimball, Hinckley, and Packer informed him that the position was “not a ‘call,’ but a job”—a job that included a significant cut in pay, no less—and informed Arthur that he “would have to decide.” After counseling with his beloved seminary teacher, Harold B. Lee, Arthur determined to accept the position and once again found himself in immersed in missionary work. [90] This position frequently found Arthur answering phone calls at his desk “long after hours,” but Arthur found the work to be exciting, challenging, and enjoyable. [91]

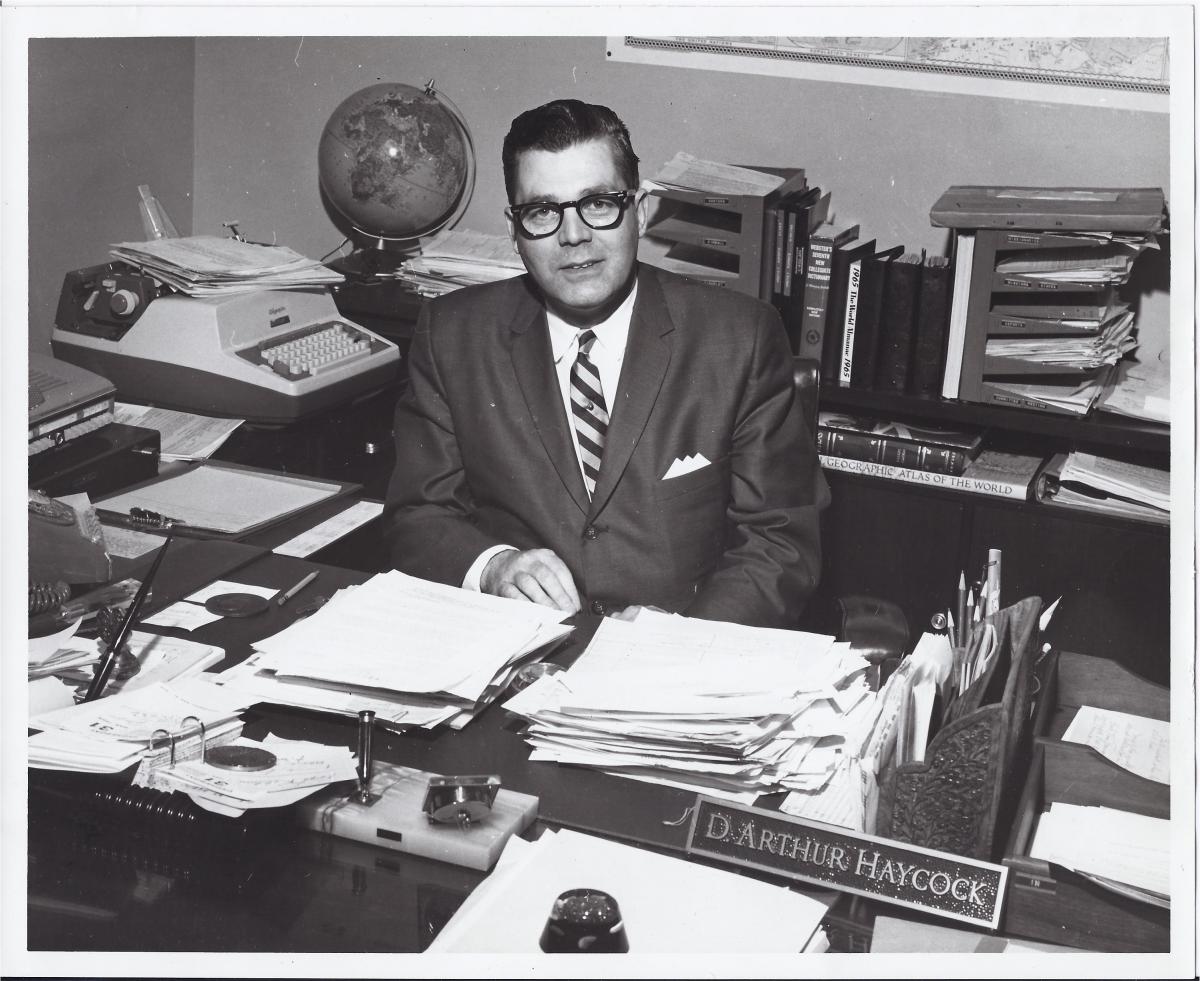

Photo of Arthur Haycock at his desk in the Missionary Department while serving as the executive secretary of the Missionary Department, ca. 1963.

Photo of Arthur Haycock at his desk in the Missionary Department while serving as the executive secretary of the Missionary Department, ca. 1963.

Although Arthur had wanted to remain with the missionary committee, his formal connections to the missionary department ended in the late 1960s when he was assigned to be the secretary to the Quorum of the Twelve. [92] Then, in 1970, when Joseph Fielding Smith became President of the Church, Arthur was once again asked to serve as personal secretary to the President, a position that he continued to hold until his retirement in 1986. Serving in this capacity, Arthur witnessed one of the most dynamic periods of growth in the Church’s history.

Unto Every Nation

Without question, one of the most important missionary-related experiences of Arthur’s experience as secretary came as President Kimball addressed the Regional Representatives Seminar in April 1974. During that meeting, President Kimball called upon the Regional Representatives and the membership as a whole to expand their missionary efforts. He rhetorically asked, “Are we prepared to lengthen our stride? To enlarge our vision?” [93] To accomplish this work, he called upon parents and leaders to better train young men so that every worthy and able young man might serve a mission. Arthur attended that meeting as both the President’s secretary and as a Regional Representative. In later years, as Arthur spoke to groups of Saints throughout the world, he drew upon the theme of missionary work. [94]

Traveling with President Kimball and the First Presidency throughout the world, Arthur witnessed at close proximity the Church’s worldwide growth during the 1970s and 1980s. President Kimball’s efforts to extend the gospel throughout the world even included visits to communist countries in the Soviet Bloc. In August 1977, Arthur was a member of the group that accompanied President Kimball to Warsaw to dedicate Poland for the preaching of the gospel. [95] Immediately following the visit to Poland, President Kimball’s party visited East Germany, where he spoke to the anxious Saints, some of whom “even stood on ladders placed outside the windows so that they could hear the proceedings.” [96]

The worldwide expansion of the Church was a tremendous blessing, but it was not without challenges. Among those challenges was the increasingly perplexing question of the priesthood ban. The priesthood restriction had been a difficult and often painful question in the Church for decades, and one that Arthur had witnessed firsthand. While serving as a young elder, Arthur came into contact with Brother John Pea, a branch clerk in Hilo who was active in genealogy work. While compiling his genealogy, Brother Pea had discovered that he had African ancestry. When the matter was presented to the First Presidency, Arthur was given unwelcome task of informing him “that he could no longer exercise his priesthood,” although he continued to function as branch clerk. In spite of the blow that this news brought to Brother Pea, he remained active in the Church. [97] Doubting some of the information in the research, Arthur interceded with the First Presidency for Brother Pea when he became President Smith’s secretary and then again when he became mission president and eventually secured the Presidency’s permission to allow Brother Pea to “go to the temple and have the priesthood.” Having been the one who told the Peas that “they couldn’t have the priesthood” as a young elder, Arthur was “happy to be able to have something to do with them finally getting to the temple.” [98] Although Arthur stood by and defended the Church’s policy, the experience with Brother Pea had provided him with tangible evidence of how difficult and complicated its implementation often was. Such experiences were not uncommon during the mid-twentieth century, and Arthur likely became aware of several other like cases as plans for the dedication of the São Paulo Brazil Temple went forward during the 1970s. [99] Thus it was with great joy that Arthur recorded in shorthand the Church’s official statement announcing the revelation extending the priesthood to all worthy males in 1978. [100]

Corresponding with the Church’s worldwide expansion was an expansion of the Church’s missionary force. In 1976, President Kimball dedicated the Language Training Mission in Provo to help train missionaries to learn foreign languages. In 1978, “the facility was enlarged and renamed the Missionary Training Center.” [101] Arthur was present at the dedication of the MTC but unfortunately did not leave his feelings about the development on record. Considering the care that Arthur showed for the training of his missionaries in Hawaii during the 1950s, however, it is likely that he viewed the event as a long-awaited blessing.

Last Mission to Hawaii and Grandfather of Prospective Missionaries

In 1986, Arthur retired from his position at the Church, and he and Maurine were called to return to Hawaii, this time to preside over the Laie Hawaii Temple. Although this position had little to do with the Church’s formal missionary labors, it served as something of a capstone to Arthur’s lifetime of missionary work. The work in the temple, however, provided Arthur with an opportunity to return to the land that he had learned to love as a missionary and to see the culmination of missionary efforts as he sealed families together in the temple.

During the last six years of his life, Arthur’s connections to the missionary program were those of a grandfather with missionary grandsons. He encouraged his grandsons to prepare for missionary service, and then as they served, he admonished them to work hard and to listen to their leaders. Once, he had the opportunity to visit and have dinner with his grandson David, who was serving in Japan. Although his visit had a familial purpose, Arthur extended care and concern to David’s companions. [102] In the decade following Arthur’s death, three other grandchildren served missions and benefitted from the example of his years of missionary service. [103]

Conclusion

Throughout his various missionary experiences, Arthur Haycock witnessed a profound change in the program and procedure of the Church’s proselyting efforts. It grew from a program that relied heavily upon the sacrifices of families that were willing to send their fathers on missions into a program that utilized the youth and vigor of young and inexperienced single adults. To compensate for these young missionaries’ lack of formal Church experience, the Church developed a vast array of training programs to help them to optimize their missionary experiences. At the same time, Arthur’s experiences revealed that the underlying principles of faith and sacrifice remained central to the success of missionary work. From Arthur’s life experiences, we can see twentieth-century missionary work was characterized by both change in its participants and formal structures and continuity in its aim and principles.

Notes

[1] Among his friends, Brother Haycock was known simply as Arthur. Accordingly, throughout this paper I will refer to him as Arthur.

[2] Following World War I, the United States was thrown into a short depression that lasted until 1921 for the majority of the country. For Utah and the Intermountain West, however, “the depression was not merely temporary because of its effects upon agriculture, mining, and manufacturing.” Thomas G. Alexander, “The Economic Consequences of the War: Utah and the Depression of the Early 1920s,” in A Dependent Commonwealth: Utah’s Economy from Statehood to the Great Depression, ed. Dean May (Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Press, 1974), 57, 60.

[3] Lily Edith Crane Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock: A Review of Arthur’s Life by His Mother,” unpublished manuscript, 6, copy in author’s possession.

[4] Arthur nearly drowned when a group of bullies had “held him by the heels and stuck him head first into a . . . 55 gallon drum of water,” while his brother Gordon was miraculously healed after being tragically run over by a harrow. Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock,” 7; D. Arthur Haycock, “Personal History of D. Arthur Haycock,” unpublished manuscript, 2–4, copy in author’s possession.

[5] Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock,” 5.

[6] Haycock, “Personal History,” 3.

[7] Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock,” 6.

[8] Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock,” 5.

[9] Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock,” 6.

[10] Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock,” 7.

[11] This joy was somewhat tempered by David and Lily’s daughter Donna, who “wouldn’t have anything to do with [David]” for a time, having been only eight months old when David had left on his mission. Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock,” 7–8.

[12] Haycock, “Personal History,” 3–4.

[13] Though a large percentage of the Church’s early missionary force was composed of married men, there were a few others like Joseph F. Smith and Lorenzo Snow, who served as teenaged boys and single adults, that bore a closer resemblance to today’s missionary force.

[14] Haycock, “Personal History,” 61; Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock,” 11.

[15] Hawaii Honolulu Mission Manuscript History, September 29, 1954, LR 3695 2, reel 5, Church History Library, Salt Lake City; D. Arthur Haycock to Harold B. Lee, April 10, 1956, in author’s possession; D. Arthur Haycock to George Q. Cannon, February 1, 1964, in author’s possession; Heidi S. Swinton, In the Company of Prophets: Personal Experiences of D. Arthur Haycock with Heber J. Grant, George Albert Smith, David O. McKay, Joseph Fielding Smith, Harold B. Lee, Spencer W. Kimball, and Ezra Taft Benson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1993), 71–72.

[16] D. Arthur Haycock, Oral History, January 14, 1992, OH 2288, 4, Church History Library.

[17] Haycock, “Personal History,” 7.

[18] Gordon B. Hinckley, sermon at the funeral of D. Arthur Haycock, March 1, 1994, D. Arthur Haycock Funeral Services, Church History Library. One Civilian Conservation Corp participant from Connecticut said, “The CCC kept a lot of kids out of jail, I think. It scattered them all over and taught them how to live with each other, how to get along, and how to work. They got into a different environment and found out about a lot of different things they didn’t even know existed.” Toddy Wozniak, Oral History, July 10, 1971, 2, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[19] Haycock, Oral History, 27, Church History Library.

[20] D. Arthur Haycock to Maurine McClellan, May 20, 1935, in author’s possession.

[21] Elder and Sister Stuart A. Durrant served contemporaneously with Arthur. While serving their mission, the couple had a son, whom they named Stuart Olani Durrant. Years later, while Arthur served as mission president, Olani was called as a missionary to the Hawaii Mission (D. Arthur Haycock to Maurine McClellan, May 27, 1936, in author’s possession; D. Arthur Haycock to Stuart A. Durrant, May 17, 1956, in author’s possession).

[22] Haycock, “Personal History,” 8–9.

[23] Haycock, “Personal History, 9.

[24] R. Lanier Britsch, Moramona: The Mormons in Hawaii (Laie, HI: Institute for Polynesian Studies, 1989), 154–55.

[25] Haycock, “Personal History,” 9.

[26] Haycock, Oral History, 5, Church History Library.

[27] Haycock, Oral History, 5, Church History Library.

[28] There is some confusion over the cause of Larry’s death. Arthur’s letter to Maurine in 1935 states that it was from influenza, while his personal history attributes the cause of death to a ruptured appendix. See Haycock, “Personal History,” 13; D. Arthur Haycock to Maurine McClellan, November 6, 1935.

[29] D. Arthur Haycock to Maurine McClellan, May 17, 1935; D. Arthur Haycock to Maurine McClellan, May 24, 1935; D. Arthur Haycock to Maurine McClellan, June 1, 1935.

[30] Haycock, “David Arthur Haycock,” 13.

[31] Haycock, “Personal History,” 10–11.

[32] Swinton, In the Company of Prophets, 7.

[33] D. Arthur Haycock to R. Lanier Britsch, February 26, 1990, in author’s possession.

[34] D. Arthur Haycock to Maurine McClellan, August 16, 1935, in author’s possession.

[35] Haycock, “Personal History,” 14.

[36] Haycock, “Personal History,” 15–16.

[37] Haycock, Oral History, 5–6, Church History Library.

[38] Haycock, Oral History, 7, Church History Library; Sheri L. Dew, Go Forward with Faith: The Biography of Gordon B. Hinckley (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1996), 128.

[39] Haycock, Oral History, 7–8, Church History Library.

[40] Haycock, Oral History, 7, Church History Library.

[41] See Haycock, “Personal History,” 24–25. To one sister missionary, he wrote, “A Mission is one of the truly glorious experiences ever to come into anyone’s life. We know that you are enjoying every minute of it. Your family is so proud of you and the swell job you are doing. And not only that, we are proud of you. . . . You may be confident that you have the united faith and prayers of all here in the Ward. . . . We look forward to the time when you return and can bless the Ward with your rich experiences and talents.” D. Arthur Haycock to Evelyn Taylor, May 1, 1947, letter in possession of Ardis E. Parshall, Salt Lake City. My thanks to Ardis Parshall for sharing a copy of this letter with me.

[42] Haycock, Oral History, 11, 14, Church History Library.

[43] Arthur relates that some questioned why President Smith spent so much time with the Reorganized Church. President Smith characteristically responded, “They are my kinfolk. . . . I’m an old man, and in the normal course of events, I will soon go to the other side. When I do, if my kinsman, the Prophet Joseph, isn’t there to meet me, I’m going to look him up. After we’ve embraced, I’ll stand back and say, ‘Brother Joseph, I want you to know that while I was on the other side, I did everything in my power to bring your own flesh and blood into the church for which you gave your life.’ I don’t want to have to hang my head.” Haycock, Oral History, 15, Church History Library.

[44] Haycock, Oral History, 16, Church History Library.

[45] Audrey L. Warren to D. Arthur Haycock, ca. June 1954, note in author’s possession.

[46] Entry for August 13, 1954, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History and Historical Reports, reel 5, Church History Library.

[47] Entries for October 17, 1953, and March 16–17, 1953, John Taylor Home Journal, MS 139, Church History Library.

[48] Gregory A. Prince and William Robert Wright, David O. McKay and the Rise of Modern Mormonism (Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 2005), 232–34.

[49] Henry D. Moyle, quoted in Prince and Wright, David O. McKay, 233.

[50] Haycock, “Personal History,” 38–39.

[51] Haycock, “Personal History,” 40; Haycock to McClellan, August 16, 1935. Following Arthur’s resignation from the Department of Agriculture, Secretary Benson wrote to Arthur, “While we regret to have you leave, we take great satisfaction that one of our number has been so highly honored.” Ezra Taft Benson to D. Arthur Haycock, June 7, 1954, in author’s possession.

[52] Carlyle S. Miller to D. Arthur Haycock, March 11, 1954, in author’s possession; Daken K. Broadhead to D. Arthur Haycock, March 16, 1954, in author’s possession; Karl D. Butler to D. Arthur Haycock, April 13, 1954, in author’s possession. Douglas R. Stringfellow, a Congressional representative from Utah, wrote, “Although I am sure the Secretary is deeply regretful in losing a person of your caliber, still I personally feel the people of Hawaii could not obtain a more conscientious or ideal L.D.S. leader than yourself.” Douglas R. Stringfellow to D. Arthur Haycock, March 2, 1954, in author’s possession.

[53] D. Arthur Haycock to I. Munroe Ferrell, March 11, 1954, in author’s possession.

[54] D. Arthur Haycock to Karl D. Butler, ca. April 1954, in author’s possession. Arthur had made a second visit to the islands in 1950, with George Albert Smith.

[55] D. Arthur Haycock to Ernest A. Nelson, April 15, 1954, in author’s possession.

[56] Haycock to Nelson, April 15, 1954.

[57] The sale of the Haycock’s home came just as the family was leaving Virginia. On the way out of town, Arthur stopped by the bank only to learn that a deal to sell the house had fallen through. Upon learning this, Arthur “stepped into the other room and said a prayer.” As Arthur returned to the office, “the phone rang, and it was a bank asking if they had any mortgages to sell.” Haycock, “Personal History,” 40–41.

[58] Haycock, “Personal History,” 42–43; entry for June 21, 1954, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[59] Entries for June 25–27, 1954, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[60] Entry for December 8, 1937, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[61] Exact numbers of missionaries and baptisms are not available for 1954. These numbers are based upon later statistics.

[62] D. Arthur Haycock to Delbert L. Stapley, June 19, 1956, in author’s possession.

[63] Maurine M. Haycock to Haycock girls, March 31, 1955, in author’s possession.

[64] “Pres. Haycock Returns from Hawaii Mission,” Church News, August 9, 1958, 5.

[65] Britsch, Moramona, 199.

[66] Undated entry ca. September 29, 1954, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[67] Entry for October 30, 1954, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[68] Entry for December 20, 1954, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library; Honolulu District, entry for December 5, 1954, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[69] Entry for December 27, 1954, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[70] Entry for February 2, 1955, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[71] Entries for March 6, 20, and 27, 1955, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[72] Arthur informed the missionaries that this class was not “optional” but was a “required” and “integral part of each missionary day.” The mission schedule set apart the hour from 8:30 to 9:30 a.m. for language study. Hawaii Mission Presidency to missionaries, May 25, 1955, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[73] Hawaii Mission Presidency to missionaries, May 25, 1955, Church History Library.

[74] Haycock, Oral History, 37, Church History Library.

[75] Arthur’s idea was not altogether unique during this period. During the 1920s and 1930s, John A. Widtsoe had pushed for the release of missionaries from positions of ecclesiastical leadership. See Alan K. Parrish, John A. Widtsoe: A Biography (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 460–65. Both A. Theodore Tuttle and David O. McKay had encouraged Church leaders to elevate local members to leadership positions. See Prince and Wright, David O. McKay, 369–70.

[76] Haycock, Oral History, 37, Church History Library.

[77] Haycock to Durrant, May 17, 1956. Describing the decision to a former Hawaii missionary, Arthur wrote, “This gives them the feeling of belonging, and as they assume the responsibility they grow and develop, and the Lord magnifies them in their callings.” D. Arthur Haycock to Ululani Kamauoha, June 16, 1956, in author’s possession.

[78] Haycock, Oral History, 37, Church History Library; “The L.D.S. Church Turns to Local Leaders,” November 1955, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[79] Haycock, Oral History, 37–38, Church History Library.

[80] D. Arthur Haycock, Diary, August 19, 1957, in author’s possession.

[81] Entry for July 29, 1957, Hawaii Honolulu Mission, Manuscript History, Church History Library.

[82] D. Arthur Haycock, Diary, August 22, 1957, in author’s possession.

[83] Haycock, Oral History, 44–45, Church History Library. Speaking of the family’s finances on the return home, Arthur wrote, “We used our last $20.00 to buy food on the train the night before we arrived.” Haycock, “Personal History,” 45.

[84] Haycock, Oral History, 45, Church History Library.

[85] D. Arthur Haycock to Alfred Wesemann, August 15, 1956, in author’s possession.

[86] Thomas S. Monson, sermon at the funeral of D. Arthur Haycock, March 1, 1994, D. Arthur Haycock Funeral Services, Church History Library.

[87] Haycock, Oral History, 45, Church History Library.

[88] “Personnel Named for Missionary Committee,” Church News, May 18, 1963, 6.

[89] Arthur’s personal history says that this occurred in 1962. Based upon contemporary evidence, however, 1963 seems to be more likely.

[90] Haycock to Cannon, February 1, 1964; Haycock, “Personal History,” 47–48.

[91] Boyd K. Packer to D. Arthur Haycock, May 21, 1966, in author’s possession; Haycock, “Personal History,” 48.

[92] Haycock, “Personal History,” 48.

[93] Spencer W. Kimball, “When Will the World Be Converted?,” Ensign, October 1974, 5.

[94] At the Guatemala Area Conference, Arthur related a visit with President Kimball to one stake in which “President Kimball was urging them to procure more missionaries.” Somewhat flustered, the stake president asked, “President Kimball, just how many missionaries do you want?” to which President Kimball responded, “I want all of them. There is no quota—all of them.” D. Arthur Haycock, discourse, February 22, 1977, in Official Report of the Guatemala Area Conference of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, 20.

[95] Edward L. Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride: The Presidency of Spencer W. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2005), 135–38.

[96] Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride, 138–39.

[97] Haycock, Oral History, 29–30, Church History Library.

[98] Haycock, Oral History, 30–31, Church History Library.

[99] Mark L. Grover, “The Mormon Priesthood Revelation and the São Paulo, Brazil Temple,” Dialogue 23, no. 1 (Spring 1990): 39–53.

[100] Swinton, In the Company of Prophets, 83.

[101] Kimball, Lengthen Your Stride, 115–16.

[102] David Buchanan to Brett D. Dowdle, email, February 20, 2011.

[103] Arthur’s daughter Lynnette H. Dowdle often sent words of counsel and advice to her sons that she had found in letters that her father had written to his missionaries.