Justice, Mercy and the Atonement in the Teachings of Alma to Corianton

Daniel B. Sharp

Daniel B. Sharp, "Justice, Mercy and the Atonement in the Teachings of Alma to Corianton," in Give Ear to My Words, ed. Kerry Hull, Nicholas J. Frederick, and Hank R. Smith (Religious Studies Center, Brigham Young University; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2019), 73–88.

Daniel B. Sharp was an associate professor of religious education at Brigham Young University—Hawaii when this was written.

Alma 42 begins, “And now, my son, I perceive there is somewhat more which doth worry your mind, which you cannot understand—which is concerning the justice of God in the punishment of the sinner; for ye do try to suppose that it is injustice that the sinner should be consigned to a state of misery” (Alma 42:1). Alma, speaking in this passage to his son, Corianton, draws upon the Nephite knowledge of the fall, redemption, and concepts of God’s justice and mercy to answer his son’s concern. My purpose in this paper is to explore Alma’s understanding of these doctrines, with a particular emphasis on his concept of justice.

At the outset, it is important to recognize that the Lord speaks to his prophets “line upon line, precept upon precept, here a little and there a little” (2 Nephi 28:30). Because of this fact, not everything that has been revealed through our prophets today was revealed to the ancient prophet Alma. This paper will focus on Alma’s understanding of justice and mercy and allow for the possibility that his understanding may differ from ours in the latter days.[1]

Background

Alma 39–42 takes place within the larger context of Alma’s counsel to his three sons in Alma 36–42. In chapters 39–42, Alma counsels with his son Corianton, who had recently forsaken the ministry to go after a harlot (Alma 39:3). Alma admonishes his son to repent and return to the ministry (Alma 39:5–16; 42:31). Alma also takes this time to elaborate on some doctrines that are troubling his son (Alma 39:17; 40:1; 41:1; 42:1). Ultimately, Corianton repents and returns to the ministry (Alma 49:30).

The Fall

In attempting to get his son to understand the justice of God in punishing the sinner, Alma begins by reiterating to him the doctrine of the fall (Alma 42:2–12). Alma explains to Corianton that because of the fall, this life became a probationary state. He introduces this concept in verse 4 and then elaborates on it until verse 10. God had promised that if Adam partook of the fruit of the knowledge of good and evil he would die, and thus, if Adam had been allowed to eat of the tree of life without dying, “the word of God would have been void” (42:5). Thus it was appointed unto humans to die (42:6), and this death passed on to all.

Alma further explains that not only had a temporal death come upon humanity, but also a spiritual death (Alma 42:7). Alma explains that spiritual death means to be “cut off from the presence of the Lord” (42:9). It was important for the great plan of happiness that people should experience a temporal death. Alma told Corianton, “It was not expedient that man should be reclaimed from this temporal death, for that would destroy the great plan of happiness” (42:8). The soul, however, could never die, and it was expedient that this soul should be reclaimed from its spiritual death (42:9).

This is Alma’s view of the first great effect of the fall: it caused a spiritual separation of all humanity from God. This separation is not because of our personal sins, but rather is the result of the fall of Adam. Even if, hypothetically, a sinless human lived upon the earth, if there had been a fall but no redemption from that fall, upon death that perfect person would still be separated from God for all eternity. This idea is explained by the prophet Jacob. Alma, who was up to this time the keeper of the Nephite records, had access to and no doubt was familiar with this teaching of Jacob.[2] Jacob taught, “For behold, if the flesh should rise no more”—that is, as if there were no redemption from the separation from God—“our spirits must become subject to that angel who fell from before the presence of the Eternal God, . . . and our spirits must have become like unto him, and we become devils” (2 Nephi 9:8–9).

Here Jacob teaches that without the resurrection of the dead—without that redemption from the spiritual death caused by the fall of Adam—all humanity would be hopelessly lost to the devil, regardless of their personal actions. Alma summarizes this same idea when instructing Corianton this way, “And the resurrection of the dead bringeth back men into the presence of God; and thus they are restored into his presence” (Alma 42:23). Alma has already taught that the spiritual death caused by the fall was a separation of the soul from God’s presence (42:9). Here he teaches that the resurrection restores humanity into the presence of God, thus redeeming humanity from the fall.

There is, however, another effect of the fall. After introducing in Alma 42:9 the idea of the universal spiritual death caused by the fall, Alma writes, “Therefore, as they had become carnal, sensual, and devilish, by nature, this probationary state became a state for them to prepare; it became a preparatory state” (42:10). In addition to the universal separation from God caused by the fall of Adam, there is also the personal separation from God that is caused by our own carnal nature.[3] In these passages (42:2–12), Alma explains to Corianton that the reason this life has become a preparatory state is because humanity will be redeemed from the spiritual death caused by Adam. If there was no redemption from that spiritual death, this life would be a hopeless state. But, because there was a redemption, it is now a time to prepare for that return to God’s presence. Alma makes it clear to Corianton that the return to God’s presence is followed by a personal judgment—“the resurrection of the dead bringeth back men into the presence of God; and thus they are restored into his presence, to be judged according to their works” (42:23).

In order to enlighten Corianton on the justice of God in punishing the sinner, Alma outlined that since the fall, this life has become a preparatory state. He explained to Corianton that the universal separation of humanity caused by the fall will be overcome by the universal resurrection brought about by the resurrection of Jesus Christ, which shall restore all people to the presence of God. This restoration, however, occurs so that people can then be judged according to their works. Thus life is a time to prepare for that restoration to God’s presence.

The use of the word restore in this scripture is not accidental. Alma had just spent a great deal of time explaining the idea of restoration to his son Corianton (Alma 40:2–41:15). Corianton’s inability to understand the justice of God in the punishment of the sinner is due to his misunderstanding of the justice of God, which, as Alma taught, is wrapped up in the concept of the restoration. Therefore, before continuing the exegesis of Alma 42, it is necessary here to review the concepts of restoration and justice, which Alma already outlined to Corianton in chapters 40 and 41.

Restoration and Justice

Alma explains that the plan of restoration is “requisite with the justice of God” (Alma 41:2). In the English versions of the scriptures used by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the word requisite appears only six times. All six are from the Book of Mormon, and four are from Alma chapter 41.[4]

It is difficult, if not impossible, to know what reformed Egyptian word or Hebrew word was upon the gold plates that Joseph Smith translated as the English word requisite. One can only say that Joseph Smith chose the English word requisite to represent the idea that was pressed into his mind in this passage.[5] According to Webster’s 1828 dictionary, the word requisite means “required by the nature of things or by circumstances; necessary; so needful that it cannot be dispensed with.”[6] Thus restoration is required, so needed it cannot be dispensed with, according to God’s sense of justice.

Alma goes on to explain that restoration is not only the idea that the soul and body should be reunited (Alma 40:23; 41:2), but also that people should be restored good for good and evil for evil. Alma asks his son, “Is the meaning of the word restoration to take a thing of a natural state and place it in an unnatural state, or to place it in a state opposite to its nature?” (Alma 41:12). Then he answers his own question and explains that “restoration is to bring back again evil for evil, or carnal for carnal . . . good for that which is good; righteous for that which is righteous” (41:13).

It is this latter idea of restoration, the restoring good for good and evil for evil, that ties restoration in with God’s justice. For, as Alma explains, the justice of God has its own requirements, “And it is requisite with the justice of God that men should be judged according to their works” (Alma 41:3). In God’s plan, it is “so needful that it cannot be dispensed with” that people should be judged according to their actions and then held accountable. If they have done good, they must be restored to that which is good. If they have done evil, then it is requisite with the justice of God that they should be restored to that which is evil (41:3–5). Justice and restoration work hand in hand, so that one cannot exist without the other. For Alma, the work of justice is to restore good rewards for good actions and evil rewards for evil actions, “For that which ye do send out shall return unto you again” (41:15).

Justice and the Fall

As already outlined above, Alma has explained to Corianton that there were two great effects of the fall. First, it caused a universal separation from God’s presence. Regardless of human action, regardless of personal sin or personal righteousness, all humanity was cut off from God’s presence and damned by the fall. Thus, the first effect of the fall made it so that people were not held accountable for their actions, but rather were condemned because of Adam.[7] This is clearly unjust, since justice demands that people be judged according to their works (Alma 41:3–6). Thus it is requisite with the justice of God that people be restored to God’s presence, regardless of their actions. As they had been removed from God’s presence through no fault of their own, they would be restored to God’s presence through no merit of their own.[8] This restoration of all people to God’s presence is the first step in satisfying the demands of God’s justice. The justice of God, however, requires that people be held accountable for their actions. The restoration returns everyone to God’s presence, redeeming them from the fall of Adam so that they can now be personally accountable.

All of this is clearly taught by Father Lehi, who, after explaining that there would be a fall caused by Adam, wrote, “And the Messiah cometh in the fulness of time, that he may redeem the children of men from the fall. And because that they are redeemed from the fall they have become free forever, knowing good from evil; to act for themselves and not to be acted upon” (2 Nephi 2:26). Had it not been for the Messiah who would provide a redemption from the fall, all mankind would not be accountable, and this would be unjust. The redemption from the fall was not a way to escape the justice of God; rather, it is the justice of God that required a redemption from the fall so that humanity could be free to choose for themselves and could thus be held accountable for their actions.

The second effect of the fall, however, was that humanity became “carnal, sensual, and devilish” (Alma 42:10) and thus committed personal sin that would ultimately condemn them during their judgment. If God through his infinite mercy allowed sinners to dwell in his presence, this would be against the justice of God because justice requires that people be held accountable for their actions; the unrepentant sinner must be restored to evil because of the evil he had done. That is the demand of justice.

Alma explains, however, that God prepared repentance. As the justice of God requires that someone who does evil is restored to evil, the justice of God equally requires that one who has gone through repentance be restored to good. Mercy does not entail escaping the demand of justice—mercy is the demand of justice for the penitent.

This relationship between justice and mercy is outlined by Amulek, Alma’s former missionary companion. After discussing that an infinite and eternal atonement would be made, Amulek taught,

And thus he shall bring salvation to all those who shall believe on his name; this being the intent of this last sacrifice, to bring about the bowels of mercy, which overpowereth justice, and bringeth about means unto men that they may have faith unto repentance. And thus mercy can satisfy the demands of justice, and encircles them in the arms of safety, while he that exercises no faith unto repentance is exposed to the whole law of the demands of justice; therefore only unto him that has faith unto repentance is brought about the great and eternal plan of redemption. (Alma 34:15–16)

In this passage, Amulek explains that justice can be satisfied in one of two ways: by mercy or by being exposed to the law. The deciding factor between whether one receives mercy or is exposed to the law is based on whether or not one has exercised faith unto repentance. If one has exercised their faith unto repentance (proper action and desire), then receiving mercy and forgiveness satisfies the demand of justice that people be held accountable for their actions. If one has not repented, the only way to satisfy the demand of justice for accountability is to punish the sinner.

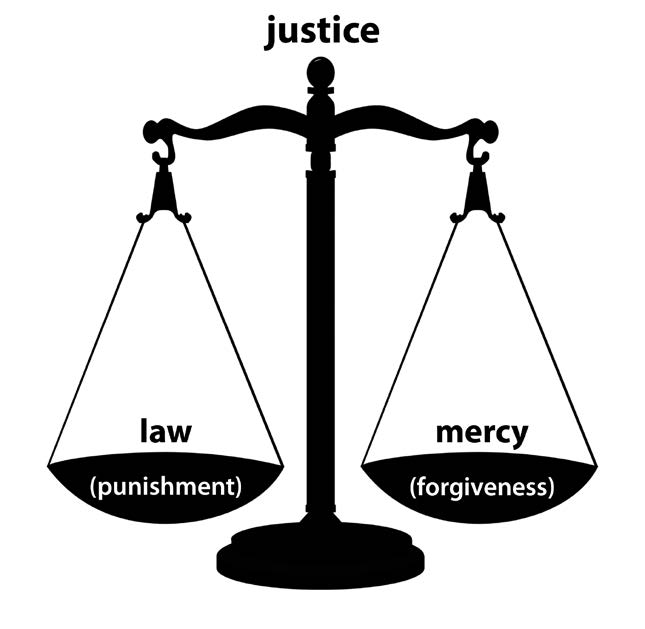

One interpretation of justice and mercy.

One interpretation of justice and mercy.

Amulek and Alma’s interpretation of justice and mercy.

Amulek and Alma’s interpretation of justice and mercy.

Sometimes justice and mercy are depicted as two sides of a scale. Amulek explains an alternative view, where the law and its consequent punishment would be the opposite of mercy and forgiveness. Rather than justice being one end of a scale, justice is the scale itself. For those who have repented, the atonement of Jesus Christ allows mercy to overpower the scale of justice and tip it away from punishment and toward forgiveness.

Abinadi, who had converted Alma’s father, also taught about the relationship between justice and mercy. After explaining that Jehovah himself would come down to earth and free people from the spiritual death caused by Adam (Mosiah 13:34–15:7), he taught, “And thus God breaketh the bands of death, having gained the victory over death; giving the Son power to make intercession for the children of men—Having ascended into heaven, having the bowels of mercy; being filled with compassion towards the children of men; standing betwixt them and justice; having broken the bands of death, taken upon himself their iniquity and their transgressions, having redeemed them, and satisfied the demands of justice” (Mosiah 15:8–9).

As in the case with the word requisite, it is also impossible to know what reformed Egyptian or Hebrew word lay behind this English translation of the word betwixt. Webster’s 1828 dictionary defines the word as “between; in the space that separates two persons or things; as, betwixt two oaks. Passing between; from one to another, noting intercourse.”[9] The other four uses of the word betwixt in the Book of Mormon seem to be synonymous with the word between. For example, “judge, I pray you, betwixt me and my vineyard (2 Nephi 15:3), or “thus commenced a war betwixt the Lamanites and the Nephites” (Alma 35:13), or “there must needs be a space betwixt the time of death and the time of the resurrection” (Alma 40:6; see Moroni 9:17). This usage does seem consistent with that in the Old Testament.[10] Notably, the first dictionary definition of betwixt is of something between two things in the sense of a location, or as joining two things. “Betwixt two oaks” could describe a hammock or a flower. The other definition is of something (or someone) passing between two things in intercourse.

Thus the image of the Messiah conjured by Amulek as standing betwixt the children of men and justice does not infer a barrier between humanity and justice.[11] Rather, in light of other scriptures, one should see the Messiah as standing betwixt humanity and justice as the bridge that brings humanity to justice. He has made repentance and mercy possible and thus can bring them to the justice they desire. Since justice demands that people be held accountable for their actions, the Messiah satisfied the demands of justice by making repentance possible.

In summary, based on the teachings of Lehi, Jacob, Abinadi, and Amulek, Alma understood that the Messiah would come not to help people escape the justice of God, but rather to allow the justice of God to take effect. Only through the resurrection of Jesus Christ could people return to God’s presence and be judged according to their actions. Also, only through the atonement of Christ could repentance take effect and thus allow our action of repentance to merit mercy.

The Justice of God in Punishing the Sinner

It is this understanding of the justice of God that allows Alma to answer the concern of Corianton. After having explained the effects of the fall in Alma 42:2–11, Alma points out that if there was no plan of redemption (42:11), then there was no means to reclaim humanity from this fallen state (42:12). “Therefore, according to justice, the plan of redemption could not be brought about, only on conditions of repentance of men in this probationary state, yea, this preparatory state; for except it were for these conditions, mercy could not take effect except it should destroy the work of justice” (42:13).

Here Alma is simply restating what has been argued above: since justice demands that people be held accountable for their actions, people cannot be given mercy and forgiveness unless they repent. Otherwise, mercy would be robbing justice, which would be demanding accountability for evil actions. Thus it is justice that requires the conditions of repentance to be part of the plan of redemption so that mercy can take effect, or in Alma’s words, “according to justice, the plan of redemption could not be brought about, only on conditions of repentance of men in this probationary state” (Alma 42:13). In order for God to be perfectly just, he must allow for repentance, “And now, the plan of mercy could not be brought about except an atonement should be made; therefore God himself[12] atoneth for the sins of the world, to bring about the plan of mercy, to appease the demands of justice, that God might be a perfect just God,[13] and a merciful God also” (42:15). The atonement of Jesus Christ, which enacts the plan of mercy, appeases what the justice of God has been demanding the entire time.

Alma next turns his attention to the conditions of repentance. He argues that justice requires that the conditions of repentance must be part of the plan of mercy. He then explains what those conditions are: “Now, repentance could not come unto men except there were a punishment” (Alma 42:16). This is a rather unusual claim, but Alma attempts to logically show that one cannot have repentance unless there is punishment. His argument is based on the idea that repentance requires such a thing as sin. Likewise, one can only sin if there is a law that one can transgress. Thus, one cannot have sin without a law. Finally, according to Alma, a law cannot exist unless there is a punishment attached to the law; therefore, one cannot have repentance unless there is punishment (42:17). Alma argues that the punishment affixed to the law gives the law its force (42:18–21). Thus, since justice requires the concept of repentance to exist in order for people to be held accountable for all their actions, justice also requires the concept of punishment to exist because there cannot be repentance without sin, sin without law, and law without punishment; therefore, if there is repentance, punishment must also exist.

“But there is a law given” Alma explains, “and a punishment affixed, and repentance[14] granted” (Alma 42:22). This is the state of humanity: they exist in this probationary state, which is a direct result of the fall. They have been given a law with clearly stated punishments if the law is broken. However, the law also has repentance built in. It is not clear from Alma’s conversation with his son if he has in mind some universal law, a set of laws, or specifically the law of Moses.[15] Either way, it is clear that repentance is built into the giving of law,[16] “which repentance, mercy claimeth” (42:22). If one repents, then one will receive mercy and forgiveness as a reward for their actions; “otherwise, justice claimeth the creature and executeth the law, and the law inflicteth the punishment” (42:22). Note that it is not justice that is inflicting the punishment— since the person did not repent, justice then turns the person over to the law, which inflicts the punishment. Alma, like Amulek before him, sees justice as the scale, determining if the actions of the person merit mercy or the law. “If not so,” if the wicked person were not punished, “the works of justice would be destroyed and God would cease to be God” (42:22). This is obviously an impossible reality; God cannot cease to be God, and thus justice cannot be destroyed, and thus all people must be held accountable for their actions. Justice will execute all of its demands—judging people according to their works—and for those that are truly penitent, mercy shall claim them as their just reward (42:23–25).

Alma would answer Corianton’s question of how God can be just in punishing the sinner by explaining that people have been given a law and told to repent. God’s justice has provided humanity with a way to return to his presence and the opportunity to repent. He has prepared, through his justice, everything needed for this plan of mercy and redemption from the foundation of the world. God then allows everyone to come and partake of this merciful plan. If they will repent, then they will receive their just reward. If, however, they choose not to repent, then justice demands that they be held accountable for their evil actions. They are then exposed to the law, which inflicts the punishment. Alma concludes, “O my son, I desire that ye should deny the justice of God no more. Do not endeavor to excuse yourself in the least point because of your sins, by denying the justice of God” (Alma 42:26–27, 30).

Conclusion

Many members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints view the justice of God as a miserable thing that one should seek desperately to avoid. They envision justice as the opposite of mercy and that the final judgment is based on God attempting to decide whether one should receive justice or mercy. Some see the purpose of the atonement of Jesus Christ as an attempt by God to circumvent administering justice to us by administering it upon his Son. Such a person has a difficult time understanding Jacob’s teaching, “Prepare your souls for that glorious day when justice shall be administered unto the righteous” (2 Nephi 9:46).

I have attempted to unfold Alma’s view of the justice of God. Alma views the atonement of Christ not as a way to circumvent justice but as the natural outcome of God’s justice. The fall had left humanity cut off from God’s presence—carnal, natural, and devilish. The justice of God required that people be held accountable for their actions. Thus, Jesus Christ returns all humanity to God’s presence so that they might be held accountable for their actions—redeeming them from the spiritual separation caused by Adam. Furthermore, this eternal sacrifice allows for repentance. This allows individuals, with the enabling power of the grace of Christ, to change their actions, to modify their behaviors, and to replace their evil acts with righteous desires. The repentance provided by the atonement of Jesus Christ allows us to be judged by the justice of God and to be found deserving of mercy.

Notes

[1] For some latter-day interpretations of these topics, see Boyd K. Packer, “The Mediator,” Ensign, May 1977, 54–56; LaMar E. Garrard, “Creation, Fall, and Atonement (2 Nephi 1, 2),” in 1 Nephi to Alma 29, ed. Kent P. Jackson (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1987), 86–102; Robert L. Millet, “The Regeneration of Fallen Man,” in Nurturing Faith through the Book of Mormon: The 24th Annual Sidney B. Sperry Symposium (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1995), 119–48; Todd B. Parker, “The Fall of Man: One of the Three Pillars of Eternity,” in The Fulness of the Gospel: Foundational Teachings from the Book of Mormon (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003), 77–90.

[2] See Alma 37 for evidence that Alma had faithfully kept the record of the Nephites. Also note that Alma 37:38–47 provides evidence that he was familiar with some of the stories upon the small plates of Nephi.

[3] As Alma made clear, our carnal nature is also a result of the fall. For a greater explanation, see Millet, “Regeneration of Fallen Man,” 122–25.

[4] The other two references are from Mosiah 4:27 and Alma 61:12.

[5] For a discussion about the misspelling of this word in the original Book of Mormon manuscript and Oliver Cowdery’s tendency to pluralize it, see Royal Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants of the Book of Mormon: Part Four Alma 21–55, The Critical Text of the Book of Mormon (Provo, UT: FARMS, Brigham Young University, 2007), 2419–20.

[6] “Webster’s Dictionary 1828—online edition,” http://

[7] Although outside the scope of this paper, this clearly contradicts the second article of faith, “We believe that men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression.” I would point out that the situation where people are condemned for Adam’s transgression is only a hypothetical situation that would happen if there was no atonement. In other words, the second article of faith is true because of the third article of faith—because there is an atonement of Jesus Christ.

[8] See also, Parker, “Fall of Man,” 84. He wrote, “Hence, the spiritual death brought about by Adam is unconditionally overcome for all mankind because they will be returned to God’s presence for judgment. . . . Thus people are accountable only for their own actions.”

[9] http://

[10] See, for example, Genesis 17:11; 23:15; 26:28; 30:36.

[11] Contra Joseph Fielding McConkie and Robert L. Millet, Doctrinal Commentary on the Book of Mormon: Jacob through Mosiah (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1987), 2:233–34; George Reynolds, Commentary on the Book of Mormon: The Words of Mormon and the Book of Mosiah (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1990), 2:17–72; Brant Gardner, Second Witness: Analytical and Contextual Commentary on the Book of Mormon: Enos through Mosiah (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2007), 3:302.

[12] Here we see the language of Abinadi influencing the language of Alma—an indicator that Alma’s theology of justice and mercy was influenced by his knowledge of Abinadi (Mosiah 13:34; 15:1).

[13] For the decision to omit the comma between the words perfect and just, as well as the argument to understand perfect with the adverbial meaning “perfectly just,” see Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants, 2436–38.

[14] For the argument to omit the word a in this verse, see Skousen, Analysis of Textual Variants, 2442.

[15] Note that the example of a law that Alma gave in verse 19 is part of the law of Moses.

[16] Clearly from an ancient Israelite viewpoint, the giving of the law of Moses came with proscribed actions and sacrifices to receive forgiveness (see Bible Dictionary, “Sacrifices”). In support of a more universal point of view, in 2 Nephi 9, Jacob, after explaining that all people will rise from the dead to stand before God to be judged writes, “And he commandeth all men that they must repent” (2 Nephi 9:22–23).