The Church in Britain before 1840

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green, “The Church in Britain Before 1840,” in The Field Is White, Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 1-21.

We need background pertaining to the history of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints in the British Isles to understand the growth and development of the Church in the Three Counties area in England (Herefordshire, Worcestershire, and Gloucestershire). On 6 April 1830, Joseph Smith formally organized the Church with a small group of attendees in Fayette, New York. The following year the body of the Church moved to Kirtland, Ohio, where they organized a settlement and built a temple.

A subsequent revelation specified Independence, Missouri, as the place where Zion would be built, so Church members began to move west to that area. The group experienced great opposition from their neighbors, and many were driven out of their homes. The following year, Joseph Smith gathered a group of members in Kirtland and formed a band of volunteers totaling around two hundred, referred to as Zion’s Camp, to travel to Missouri to regain the lost properties. When they were not successful, some of the volunteers became disgruntled and angry. As Joseph disbanded the camp, he voiced a promise from the Lord for those who had been faithful: “I have heard their prayers, and will accept their offering; and it is expedient in me that they should be brought thus far for a trial of their faith” (D&C 105:19).

In February 1835, Joseph Smith ordained the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, nine of whom had been participants of Zion’s Camp.[1] They had proven themselves through this difficult trial. This pattern would be repeated many times in the future with additional trials, just as it is repeated today: good news (the Restoration of the gospel and the designation of the geographical location of Zion), followed by trials (loss of property in Missouri and inability to regain it), followed by increased faith that ultimately leads to blessings (becoming members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles).

The pattern occurred again in 1836 when the dedication of the Kirtland Temple brought an outpouring of spiritual manifestations which many of the Saints were able to witness and record. However, by May 1837, trials had engulfed the fledgling Church. Many Church members engaged in financial speculation (prevalent through the nation); Joseph Smith described this spirit of speculation:

As the fruits of this spirit, evil surmisings, fault finding, disunion, dissension, and apostacy followed in quick succession, and it seemed as though all the powers of earth and hell were combining their influence in an especial manner to overthrow the church at once, and make a final end. Other banking institutions refused the “Kirtland Safety Society’s Notes; The enemy abroad, and apostates in our midsts united in their schemes; flour and provisions were turned towards other markets; and many became disaffected toward me as though I were the sole cause of those very evils I was most strenuously striving against; and which were actually brought upon us, by the brethren not giving heed to my council.

No quorum in the church was entirely exempt from the influence of those false spirits, who were striving against me, for the Mastery; even some of the Twelve were so far lost to their high and responsible calling, as to begin to take sides, secretly with the enemy.[2]

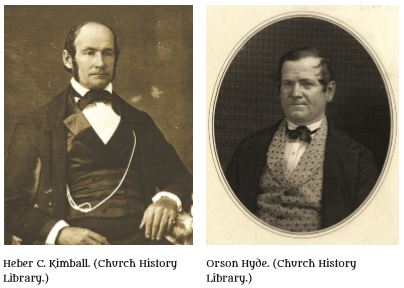

During this difficult time of financial speculation, God revealed to Joseph that “something new must be done for the salvation of his church.”[3] On 4 June 1837, Joseph spoke to Heber C. Kimball in the Kirtland Temple. Heber’s grandson Orson F. Whitney recorded the occasion as Joseph said to Heber, “Brother Heber, the Spirit of the Lord has whispered to me: ‘Let my servant Heber go to England and proclaim my Gospel, and open the door of salvation to that nation.’”[4] Heber was feeling overwhelmed and unfit for the work, so he asked if Brigham Young could accompany him. However, Joseph had other plans for Brigham. Although Heber felt a tremendous burden, his journal entry indicates his great faith:

The idea of being appointed to such an important office and mission, was almost more than I could bear up under. . . . However, all these considerations did not deter me from the path of duty . . . but the moment I understood the will of my heavenly Father; I felt a determination to go at all hazards, believing that he would support me by His almighty power; and endow me with every qualification that I needed. And although my family were dear to me, and I should have to leave them almost destitute; yet I felt that the cause of truth, the gospel of Christ, outweighed every other consideration.[5]

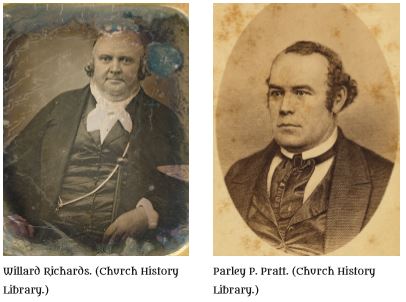

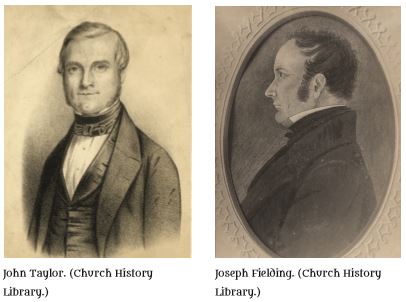

Orson Hyde was present when Heber was ordained to the mission; Orson asked forgiveness of his faults and offered to accompany Heber.[6] Willard Richards, a good friend of Heber, was also anxious to join the group and obtained permission to do so.[7] The previous year on a mission to Canada, Parley P. Pratt had introduced John Taylor to the message of the restored gospel of Jesus Christ. John had joined the Church along with Joseph Fielding; both had family in England. Joseph Fielding was in Kirtland at the time of Heber’s mission call and was ready to accompany him to England. Three other Canadian converts—John Goodson, Isaac Russell, and John Snyder—prepared to meet the group in New York. All seven missionaries sailed on the Garrick on 1 July and reached Liverpool in eighteen days. They were assisted by good weather and a wager from a rival ship, the South America, which never managed to pass the Garrick during the voyage.[8] Instead of joining the other passengers in boarding a steamer to reach shore, Elders Kimball, Hyde, Richards, and Goodson jumped in a small rowing boat and leaped onto the dock ahead of the steamer. Liverpool was England’s main port, and the port through which many emigrants left their homeland. After three days, the missionaries felt led by the Spirit to travel north by coach to the industrial city of Preston, where Joseph Fielding’s brother was a Methodist minister.[9]

Church Beginnings in Lancashire

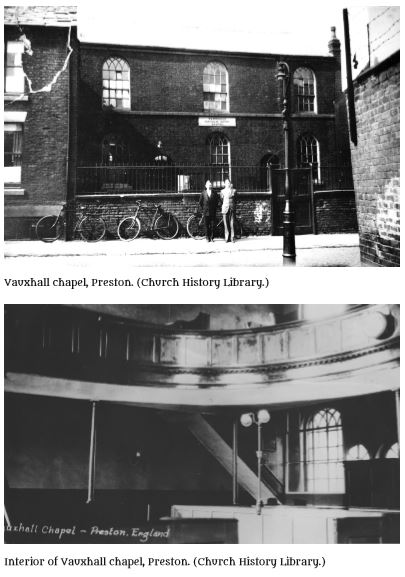

The group of missionaries arrived in Preston on 22 July during a parliamentary election. As the missionaries alighted from the coach, they noticed a gilded banner with the motto “Truth will Prevail.” Involuntarily, they exclaimed, “Amen. So let it be.”[10] While the rest of the missionaries found lodging, Joseph Fielding located his minister brother, James, who welcomed Joseph Fielding.

After James preached the following Sunday morning, 23 July, he offered to let the missionaries preach from his pulpit that afternoon. News of their arrival had spread among the community, so when the community heard that one of the elders would preach later in the day, a large number of people gathered at the Vauxhall chapel to hear them. Many people were interested in the message, so Reverend Fielding opened his chapel again to the elders the following Wednesday. Following the preaching of Elder Hyde that day, many rejoiced and wished to be baptized. At the mention of baptism and the possibility of losing his flock, James Fielding shut his doors to the missionaries. Speaking later of those first sermons, Reverend Fielding said, “Kimball bored the holes, Goodson drove the nails, and Hyde clinched them.”[11]

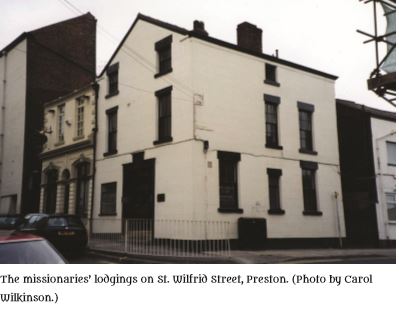

Nine people committed to baptism on Sunday, 30 July, but despite all the good news, the missionaries would face a test of their faith. That morning around daybreak, the missionaries had an encounter with satanic forces at their lodging in Wilfred Street. Isaac Russell awoke Elders Kimball and Hyde, telling them that he was afflicted by evil spirits and asked them to pray for him to receive relief. Elder Kimball described what transpired during that blessing:

While thus engaged I was struck with great force by some invisible power and fell senseless on the floor, as if I had been shot; and the first thing I recollected was, that I was supported by Brothers Hyde and Russel, who were beseeching a throne of grace on my behalf. They then laid me on the bed, but my agony was so great that I could not endure, and I was obliged to get out, and fell on my knees and began to pray, I then sat on the bed and could distinctly see the evil spirits who foamed and gnashed their teeth upon us. We gazed upon them about an hour and a half, and I shall never forget the horror and malignity depicted on the countenances of these foul spirits, and any attempt to paint the scene which then presented itself; or portray the malice and enmity depicted in their countenances would be vain. I perspired exceedingly, and my clothes were as wet as if I had been taken out of the river. . . . I felt exquisite pain, and was in the greatest distress for some time. . . . Yet, by it I learned the power of the adversary, his enmity against the servants of God, and got some understanding of the invisible world.[12]

With great faith, the missionaries overcame the effects of this terrifying experience and performed the first baptisms in England in the River Ribble. Two of the nine converts were so eager to be baptized that they raced each other to see who would be the first to reach the river. The missionaries continued to preach in Preston, experiencing both success and rejection. They decided to spread further afield, and on 1 August, Russell and Snyder went north to Alston and Goodson, and Richards went south to Bedford.[13]

Joseph Fielding continued to live at his brother’s house in Preston, but James’s feelings towards the message of the restored gospel became so bitter that the atmosphere in the home was intolerable, and Joseph left.[14] His sister Ann, who was married to the Reverend Timothy Matthews of Bedford, also rejected the gospel message along with her husband when Brothers Goodson and Richards taught it to them. Joseph wrote, “I am now as a Stranger in my Native land, and almost to my Father’s house. There is not one that I can look to with any Confidence. I am something like Joseph when sold by his Brethren. The Devil would suggest perhaps I am wrong, but it cannot be. I have too much Evidence of the Truth to give way to such a thought. May the Lord help me to stand fast in the Liberty of the Gospel and my Calling.”[15]

Although the Matthews family rejected the message in Bedford, many members of Reverend Matthews’s congregation chose to be baptized.[16] So two ministers in the Fielding family had initially opened their doors to the missionaries, and although they were not interested in the gospel message, they became instrumental in helping many to enter the waters of baptism.

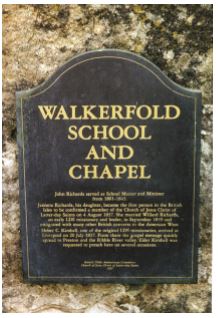

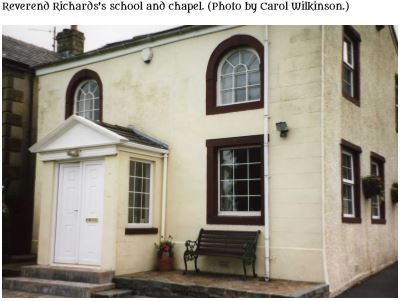

The work in Preston continued into August, and a young woman by the name of Jenetta Richards from Walkerfold, a village further up the River Ribble, was baptized and confirmed. Her father, John Richards, was a minister in Walkerfold, whose home was situated next to the chapel. He opened his doors for Elder Kimball to preach three times during the following week. But when Reverend Richards saw that members of his flock were leaving, he told Elder Kimball in a kindly way that he must close the doors of his chapel to further preaching. Other individuals opened their homes for preaching, and the elders were able to baptize several converts. The preaching continued in private homes, and Walkerfold was the first of many villages in the surrounding area to accept the message of the restored gospel.[17]

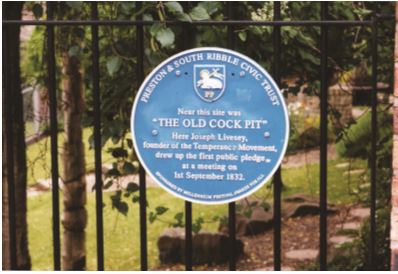

By mid-September some ninety people had joined the Church in the Preston area, and members began to meet in the centrally located “Cock Pit,” previously a site for cock fights, but at that time a meeting place for preaching and temperance groups.[18] By Christmas Day of 1837, over three hundred Saints attended the first general conference of the Church in England.[19] Elders Kimball and Hyde planned to return to America in the spring, so they began to strengthen existing congregations in addition to continuing with missionary work.

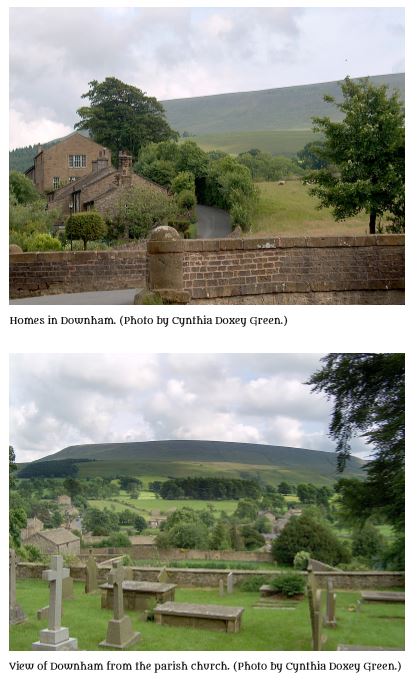

The missionary success in the villages of Downham and Chatburn on the upper River Ribble in Lancashire are noteworthy. When Elder Kimball had first mentioned his interest in going to these villages to share the gospel, local people told him that the area was wicked and the villagers were hardened against the gospel.[20] Undeterred, Heber took Joseph Fielding with him to preach in these two villages; many of the inhabitants accepted the gospel and requested baptism.

River Ribble

River Ribble

A bond of friendship developed, uniting the missionaries and their converts in Downham and Chatburn. Prior to departing for America in April 1838, Elders Kimball and Fielding experienced an emotional farewell with their new English friends. Elder Kimball described the occasion:

The next morning [the villagers] were all in tears, thinking they should see my face no more. When I left them my feelings were such as I cannot describe, as I walked down the street followed by numbers, the doors were crowded by the inmates of the houses to bid us a last farewell, who could only give vent to their grief in sobs and broken accents. While contemplating this scene we were induced to take off our hats, for we felt as if the place was holy ground—the Spirit of the Lord rested down upon us, and I was constrained to bless that whole region of country, we were followed by a great number, a considerable distance from the villages who could hardly then separate themselves from us. My heart was like unto theirs, and I thought my head was a fountain of tears, for I wept for several miles after I bid them adieu.[22]

In recounting this particular experience in Elder Kimball’s life, Orson F. Whitney described how the Prophet Joseph was able to explain the holy feeling that Heber perceived: “The Prophet Joseph told him [Heber] in after years that the reason he felt as he did in the streets of Chatburn was because the place was indeed ‘holy ground,’ that some of the ancient prophets had traveled in that region and dedicated the land, and that he, Heber, had reaped the benefit of their blessing.”[23]

On Sunday, 8 April 1838, over six hundred Saints from Preston and the surrounding area met at the Cock Pit for a mission conference. Joseph Fielding was chosen to be the mission president, with Willard Richards and William Clayton (an English convert) as his counselors.[24] The English Saints raised the money to pay for the Apostles’ trip back to America, and Elders Kimball and Hyde sailed on the Garrick on 20 April, landing in New York City on 12 May 1838. Elders Kimball and Hyde left approximately a thousand members in England.[25]

Plaque outside Walkerfold school and chapel. (photo by Carol Wilkinson)

Plaque outside Walkerfold school and chapel. (photo by Carol Wilkinson)

Difficult Times for the Church in America

During the time the missionaries had been in England, dissension had occurred within the Church, and persecution had continued from outside the Church. As a result, the Ohio Saints had left to join the Saints in Missouri. Heber arrived in Far West, Missouri, on 25 July 1838, but a couple of weeks earlier the prophet had received a revelation that would send Elder Kimball back to England accompanied by other apostles. The revelation directed the reorganization of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, calling men to take the places of those who had fallen and specifying the time that they should leave for the next mission. “And next spring let them depart to go over the great waters, and there promulgate my gospel . . . and bear record of my name. Let them take leave of my saints in the city of Far West, on the twenty-sixth day of April next, on the building-spot of my house, saith the Lord” (D&C 118:4–5).

These were trying times, as apostasy continued to be a problem in the Church. The Apostles were not immune: four of them had left the Church after the difficult times in Kirtland. By the end of 1838, Thomas B. Marsh turned against the Church and Apostle David W. Patten was killed. That same year, Governor Lilburn Boggs of Missouri issued an order that the Saints should be “exterminated,” the Hawn’s Mill Massacre occurred, Joseph Smith and several Church leaders were imprisoned in Liberty Jail, and the Saints in Missouri had to move to Illinois. Yet, during these trying times, the revelation came to send the Apostles abroad. The mission would prove to be a strengthening experience for the Apostles and would have positive ramifications for the future of the Church.

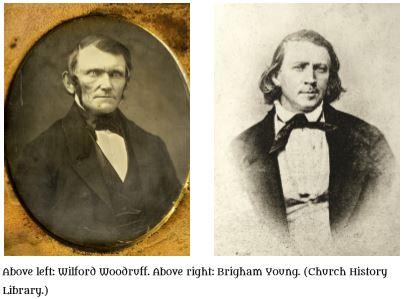

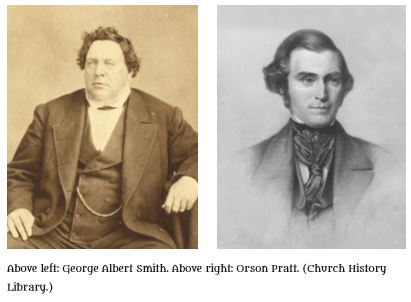

As the senior member of the Twelve Apostles, Brigham Young helped direct the move to Illinois. Despite the dangers of returning to Missouri, the brethren were determined to fulfill the direction received in Doctrine and Covenants section 118 for meeting at Far West. During the early morning of 26 April 1839, Brigham Young, Heber C., Kimball, Orson Pratt, John Taylor, George A. Smith, John E. Page, Wilford Woodruff, and eighteen other Church members met at the designated spot at Far West. After ordaining Wilford Woodruff and George A. Smith as Apostles, they held a short service and placed a symbolic cornerstone for the temple.[26] The men then quickly made their way back to Commerce, Illinois, to join the rest of the Saints. Several months would pass before any of the Apostles left for England, because they had to settle their families in Illinois.

Disease was common in the swampy area in which the Saints had settled, and they were already weak from their trials and deprivations. Yet miraculous healings rewarded the faith of many. During the summer of 1839, Joseph Smith met often with the Apostles to give them instruction on spiritual matters and leadership to help prepare them for their mission.[27]

Departure of Apostles for England

Stream location in Chatburn where early LDS baptisms were performed. (photo by Alan Wilkinson [21])

Stream location in Chatburn where early LDS baptisms were performed. (photo by Alan Wilkinson [21])

Even though they were battling sickness, Wilford Woodruff and John Taylor were the first to leave for the mission field on 8 August 1839; both were unwell for several weeks on their journey east. Brigham Young and Heber C. Kimball were the next Apostles to leave. Both were extremely ill as they prepared to depart, and their families were in a similarly dire condition. In these difficult circumstances, Brigham left Montrose, Iowa, crossed the Mississippi River, and arrived at Heber’s home in Commerce, Illinois, the same day, 16 September. His wife followed to help nurse him. The following day as Brigham and Heber left Commerce in a wagon, Heber described his feelings as he left his wife Vilate and two of their three children sick in bed: “It seemed to me as though my very inmost parts would melt within me at the thought of leaving my family in such a condition.” The two men decided to give a cheer to their families. They stood up in the wagon, and waving their hats they cried, “Hurrah, hurrah, hurrah for Israel!” Vilate got out of bed and joined Mary Ann Young in bravely calling back to their husbands, “Good bye; God bless you.” The men returned the prayer and left for their mission.[28]

Plaque designating the site of the Cock Pit. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson)

Plaque designating the site of the Cock Pit. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson)

Three other members of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles also made their way to the East as they turned their faces toward England to begin their missions: George A. Smith, followed by Parley P. Pratt and his brother Orson Pratt. Of the seven Apostles who went to the British Isles at that time, Wilford Woodruff and John Taylor were the first to arrive in England on 11 January 1840. The remaining five Apostles arrived in Liverpool on 6 April 1840. Two days later, in company with John Taylor, they traveled to Preston to hold a conference. At the conference on 14 April, they ordained Willard Richards, who had remained in England since the 1837 mission, as an Apostle.[29]

By the time the Apostles arrived from America in 1840, Church membership in Britain had increased to 1,850, and missionary work had started in Scotland.[30] With their experience, enthusiasm, and priesthood direction, the Apostles and other missionaries under their direction were able to effect further growth in the Church in England. One of the areas where the Church saw exponential growth and development was in the Three Counties area of Herefordshire, Worcestershire, and Gloucestershire, hereafter referred to as the Three Counties. The remainder of this book will focus on the Three Counties area, including the preparation of the people for the preaching of the gospel, the missionary work that proceeded there, and the contribution of the Saints who lived in that area.

Notes

[1] Record of the Twelve, 14 February–28 August 1835, The Joseph Smith Papers, http://

[2] History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 [1 September 1834–2 November 1838], http://

[3] Joseph Smith, History of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, ed. B. H. Roberts, 2nd ed. rev. (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1974), 215.

[4] Orson F. Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Bookcraft, 1967), 104.

[5] Heber C. Kimball, Journal of Heber C. Kimball (Nauvoo, IL: Robinson & Smith, 1840), 10.

[6] History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 [1 September 1834–2 November 1838], http://

[7] History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 [1 September 1834–2 November 1838], http://

[8] History, 1838–1856, volume B-1 [1 September 1834–2 November 1838], http://

[9] Kimball, Journal, 15–16.

[10] Kimball, Journal, 16.

[11] Kimball, Journal, 16–18.

[12] Kimball, Journal, 19.

[13] Kimball, Journal, 19–20.

[14] Joseph Fielding, “Diary of Joseph Fielding,” 8, BX 8670.1 .F46, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[15] Fielding, “Diary,” 10.

[16] Kimball, Journal, 24–25.

[17] Kimball, Journal, 21–23.

[18] Kimball, Journal, 25–26.

[19] On the Potter’s Wheel: The Diaries of Heber C. Kimball, ed. Stanley B. Kimball (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1987), Christmas 1837.

[20] Kimball, Journal, 33.

[21] Carol Wilkinson, “Mormon Baptismal Site in Chatburn, England,” Mormon Historical Studies 7, nos. 1 & 2 (Spring/

[22] Kimball, Journal, 34.

[23] Whitney, Life of Heber C. Kimball, 188.

[24] Kimball, Journal, 37–38; Fielding, “Diary,” 19.

[25] Fielding, “Diary,” 19.

[26] Smith, History of the Church, 3:336–39.

[27] Smith, History of the Church, 3:383–92.

[28] Kimball, Journal, 84–85.

[29] James B. Allen, Ronald K. Esplin, and David J. Whittaker, Men with a Mission, 1837–1841: The Quorum of the Twelve Apostles in the British Isles (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1992), 134.

[30] Stanley B. Kimball, Heber C. Kimball: Mormon Patriarch and Pioneer (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981), 70.