A People Prepared

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green

Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green, “A People Prepared,” in The Field Is White, Carol Wilkinson and Cynthia Doxey Green (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2017), 22-39.

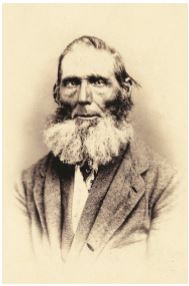

Sidney Rigdon. (Church History Library.)

Sidney Rigdon. (Church History Library.)

In 1830, Parley P. Pratt, Oliver Cowdery, Ziba Peterson, and Peter Whitmer accepted a call to serve a mission for the Church to the Lamanites in a wilderness area of the midwestern United States. Parley had recently embraced the gospel while serving a mission in western New York for the Baptist Church. He received a copy of the Book of Mormon, read it overnight, became convinced that it was true, and was baptized in September of 1830. En route to teach the Lamanites, he and his three missionary companions passed through the Kirtland area of Ohio, where they shared the gospel message with Parley’s Baptist friend Sidney Rigdon and members of Rigdon’s congregations; Rigdon and many of his followers embraced the message.

A Kirtland Comparison

The people of Kirtland were prepared to receive the gospel. Sidney was a former Baptist preacher who had become one of the founders of the Campbellite movement (named after Alexander Campbell), which focused on a return to Christian Primitivism—what they perceived as the original gospel from the time of Christ. By 1824, Rigdon could no longer agree with Campbellite doctrines. His belief in baptismal regeneration (baptism for the remission of sins) put him at odds with the Campbellites. They excommunicated him, and most of his congregation left with him (though the Baptist account does not mention this). Rigdon spoke of restoring the “ancient order of things,” which included laying all of one’s possessions down for the use of the members, which he referred to as his “common stock system.”[1] After he had joined the Latter-day Saints, a personal revelation instructed Sidney: “I have heard thy prayers, and prepared thee for a greater work. Thou art blessed, for thou shalt do great things. Behold thou wast sent forth, even as John, to prepare the way before me, and before Elijah which should come, and thou knewest it not” (D&C 35:3–4).

Like Parley P. Pratt, Wilford Woodruff experienced amazing missionary success among a people prepared for the message of the restored gospel. His success was not in Kirtland in the 1830s, but in the Three Counties area of England in 1840. This chapter considers the conditions that prevailed in England in the latter part of the eighteenth century and early decades of the nineteenth, prior to the arrival of Wilford Woodruff and his colleagues.

Social, Political, and Economic Conditions in Britain

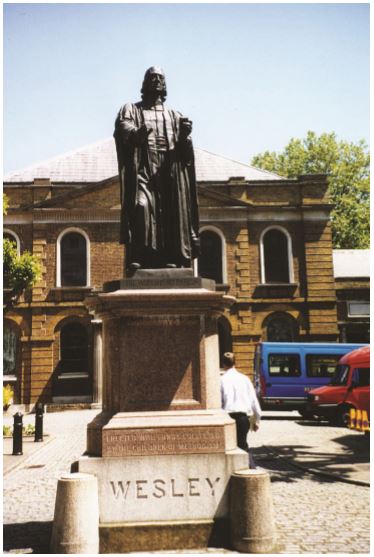

John Wesley's chapel, London, England. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

John Wesley's chapel, London, England. (Photo by Carol Wilkinson.)

During this period, the changing social, political, and economic conditions culminated in a fertile ground for a ripening crop in Herefordshire, Gloucestershire, and Worcestershire prior to the arrival of the Latter-day Saint missionaries. The population in England and Wales increased substantially from 6.5 million in 1750, to nearly 9 million in 1801.[2] Landlords wanted to try new farming methods to meet the increased demand for food for the expanding population. During the Middle Ages, cultivation had been in an open field system, with land partitioned into strips with a common area. Gradual changes had occurred over the centuries, but after 1760, the practice of enclosure greatly accelerated new practices. The landlords introduced updated farming methods to meet the increased demand for food, focusing on large-scale farming by which estates absorbed small holdings. The modern English landscape of small hedge-lined fields dates from the enclosures that existed during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. Within the villages, these changes in farming practices produced social displacement and distress for many of the inhabitants.[3]

With the onset of industrialization in the latter half of the 1700s continuing into the 1800s, many workers moved from rural areas to work in city factories. The conditions often meant working long hours and dealing with the high expense of urban living; for many families, women and children had to work to help keep households solvent. Some children had to work fourteen-hour days and occasionally nineteen-hour days. Child beatings at work were commonplace.[4] Through the 1833 Factory Act, parliament sought to limit child labor, but harsh conditions remained.

A state of unrest prevailed in England during this period due to several conditions and events: social and economic pressures associated with industrialization, the French Revolution in 1789, England’s wars with France during the Napoleonic period (until 1815), and pressures for political reform in England. As a result, in 1832 the Reform Bill was enacted by parliament to enfranchise a larger portion of the male population. In towns, the privilege to vote was given to £10 householders, and in the counties, the vote was extended to include £50 tenants. The result increased the total electorate by about a half, although the vote in England was still restricted to one man in five. This legislation first took effect in the 1837 election.[5]

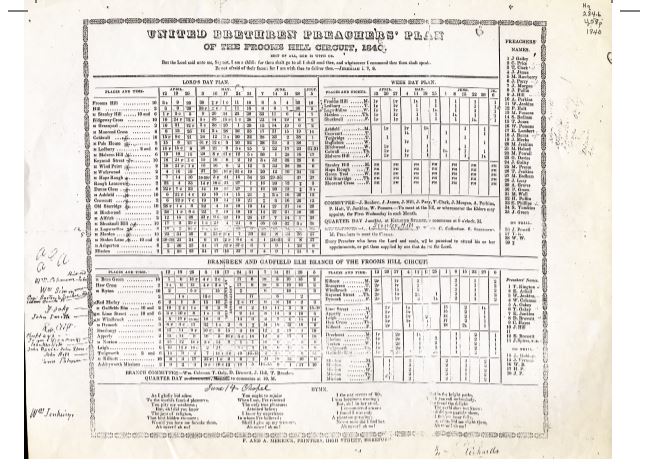

Thomas Kington, superintendent of the United Brethren. (Church History Library.)

Thomas Kington, superintendent of the United Brethren. (Church History Library.)

With the spread of the enclosures after 1760, and the increase in food prices during the French wars, the number of poor people needing help rapidly increased.[6] The New Poor Law of 1834 sought to do away with the old system of poor relief, which many felt was encouraging indolence. Under the new law, workers who had previously received government or parish aid had to labor in workhouses, where conditions were worse than the lowest paying job.[7] Economic depression during the 1830s and 1840s further exacerbated financial despair.

Religious Conditions in Britain

The years immediately following the French Revolution of 1789 brought a political component to the religious environment in Britain. The Church of England rallied in support of the establishment to preserve order and control. Sermons condoned the monarchy and condemned democracy, and the upper and upper-middle classes viewed established religion with renewed interest. Conservatives saw the parish organization of the Church of England as a way to preserve a paternalistic, hierarchical society.[8] People of lower social status were not to mingle with “their betters” on the social scale. The wife of a local parson in Warwickshire would sit in state in her pew, and the poor women had to walk up the church aisle and curtsey to her before taking their assigned seats. The squire and other individuals of status did not wish to look at agricultural laborers in the congregation, nor did they wish the laborers to gaze at them while they worshipped; so they had curtains erected to hide them from the vulgar gaze of the workers.[9]

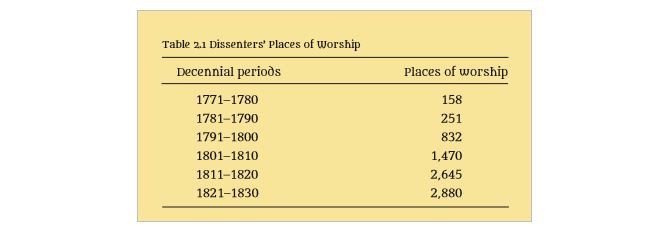

This conservative approach to maintaining order in the country discredited the Church of England for those who wanted political reform and further alienated the working classes. The 1790s saw a great acceleration in the growth of Noncomformist religions, which continued for several decades.[10] Table 2.1 shows the number of Dissenters’ places of worship for this time period. These groups included the Protestant dissenters, Congregationalists, Baptists, Presbyterians, and Quakers.[11] Table 2.1 demonstrates the burgeoning growth of dissenting religions throughout the country during these years of social and political upheaval. The largest occupational group of Nonconformists was artisans rather than the poorest people.[12]

Methodism began with John Wesley’s attempts to seek reform within the Church of England by focusing on a return to the gospel message, itinerant preaching, and “religious societies,” which were voluntary associations of clerics and laymen meeting regularly in search of spiritual fellowship unavailable in the ordinary services of the Church of England. Wesley did not wish to leave the Church of England, but the Church would not accept his ideas.[13] Methodism became a separate denomination after Wesley’s death in 1791. Methodists are not represented in table 2.1, probably because many Methodists did not register their places of worship as “Dissenters.”[14] The Methodist Church grew rapidly from the birth of the movement until 1840, when the second group of Latter-day Saint missionaries arrived in England; growth slowed from this time.[15]

Gadfield Elm chapel ruin. (Photo by Alec Mitchell.)

Gadfield Elm chapel ruin. (Photo by Alec Mitchell.)

Primitive Methodist Church. By the early years of the nineteenth century, some felt that the original mission of Wesley had been repressed by the Methodist Church. For example, Lorenzo Dow, an American Methodist who visited England between 1804 and 1807, displayed his flamboyant preaching in open-air gatherings referred to as camp meetings, which were large gatherings that focused on lay preaching and praying. Camp meetings were condemned by the English Methodist Church because such meetings condoned improper behavior.[16] English Methodists Hugh Bourne and William Clowes continued to hold camp meetings because they liked the down-to-earth manner of preaching and recognized that lay preaching in the open air had been espoused by John Wesley himself. The Methodist Church disagreed and shortly expelled Hugh Bourne and William Clowes,[17] who in 1812 formed the Primitive Methodist Church. The same year, the New Toleration Act extended the freedom accorded to Nonconformist congregations by the Toleration Act of 1689.

Wesley’s methods and organization, his teachings, and most important, his original evangelical aims, were the inspiration of the Primitive Methodist founders and leaders.[18] They believed that everyone sinned, but all could be saved if they repented of their sins. Preaching was of supreme importance to them. They considered the Bible to be the word of God, an infallible guide in life.[19] The “Ranters,” as they were called, believed God speaks directly to men through dreams and visions, so when the Bible offered no direct answer to questions, they turned to direct inspiration. Both male and female preachers were involved.

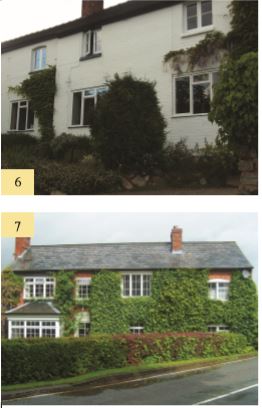

Joseph Trehern of Whiteleaved Oak. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Joseph Trehern of Whiteleaved Oak. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

This new religion appealed to the working classes. Its teachings built their self-esteem in a society that constantly told them they were rough and uncultured.[20] Becoming a Primitive Methodist meant affirming that one’s soul was important, not only in an eternal sense but to other Primitive Methodists. Working-class people were linked together in a community in which each member had responsibilities and chances to serve.[21] According to Werner, “For the inner dynamic of revivalism to function well, four prerequisites had to be met: there had to be a corps of effective revival preachers, a desire for an outpouring of the spirit, a willingness to let decorum fall by the wayside, and some means of communicating revival experiences from one place to another. The Ranters measured the worth of a preacher according to the number of souls won. Women, local preachers, and self-appointed missionaries were all welcome to participate so long as they furthered the ‘converting work.’”[22]

Letting decorum fall by the wayside was just one of the religion’s interesting behaviors. The Primitive Methodists believed in witches, “physical manifestations of the Devil, miraculous healings and special providences,” that were common in England at this time. To them, the world was a battlefield where God and the devil fought for the souls of men and women.[23] However, Primitive Methodism transformed the frustrations many Methodists felt with contemporary Wesleyanism into positive action.[24] The following describes the process of involvement in the Primitive Methodist Church:

A convert who became a Primitive Methodist did more than add his name to a membership roll. The society was less an organization than an extended family in which shared values were substituted for blood ties. To join was to be adopted into that family. Instead of traveling the way of holiness alone, the spiritual pilgrim gained the support and counsel of fellow members and was expected to reciprocate. A newcomer who asked to join, if “accounted eligible,” was given a probationary ticket and a copy of the rules. If he could read, he was to study the rules; if he was illiterate, the preacher was supposed to read and explain the regulations to him. After a quarter spent in attending meetings and endeavoring to live according to Primitive Methodist precepts, the probationary member was given a “complete” ticket and took his full place in society.[25]

A Primitive Methodist minister described the down-to-earth lay preaching methods of Primitive Methodism in the 1840s on the Yorkshire Wolds as a focus on the three Ss—shortness, sense, and salt. Many whose lives were dull and monotonous found, in the various aspects of Primitive Methodist meetings, “a life, a freedom, and a joy to which they had been strangers.”[26]

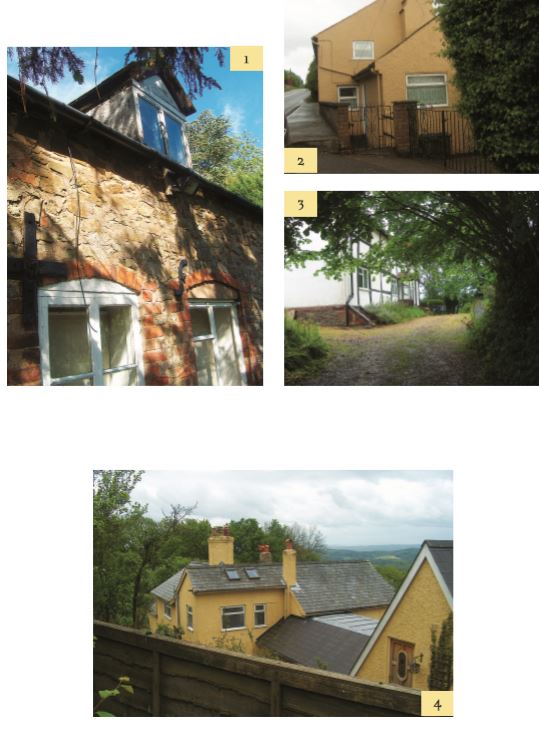

1. James Shine of Whiteleaved Oak, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

1. James Shine of Whiteleaved Oak, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

2. James Hadley of Ridgeway Cross, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

3. Benjamin Warr of Ryton, Gloucesterhire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

4. Joseph Simmonds of Wynds Point, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

James Holden of Brooms Green, Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

James Holden of Brooms Green, Gloucestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

6. William Rowley of Suckley, Worcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

6. William Rowley of Suckley, Worcestershire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

7. Sarah Davis of Bosbury, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthis Doxey Green.)

Joseph Sheen of Whiteleaven oak, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

Joseph Sheen of Whiteleaven oak, Herefordshire. (Photo by Cynthia Doxey Green.)

The United Brethren. Thomas Kington was a preacher for the Primitive Methodists who had labored in Herefordshire until May of 1832.[27] His favorite text was, “Except ye repent, ye shall all likewise perish.”[28] Sometime after leaving Herefordshire, Kington left the Primitive Methodists and founded a group known as the United Brethren. John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, had had dealings with and was influenced by the Moravians,[29] a Protestant group wishing to return the practices of the Roman Catholic Church to the purer practices of Christianity. The 1835 Primitive Methodist Magazine included the following explanation: “In the year 1453, the Hussites having done with wars, being in a suffering state, a number of them repaired to Lititz, on the borders of Moravia and Silesia, and formed themselves into a church, under the title of “THE UNITED BRETHREN.” . . . In the year 1467, the United Brethren, having received assistance from the Waldenses, desired a closer connexion with the Waldenses in Austria, but it did not take effect. It may be proper to observe, that the Moravians in England are of these United Brethren.”[30]

Thomas Kington may have been aware of this history when he decided to use the name United Brethren for his own offshoot group. A description from 1833 to 1840 of the Cwm Circuit of the Primitive Methodist Church, where Kington had labored, indicated some possible disturbances among the membership, which may have been referring to the departure of Kington and others to form the United Brethren:

While Pilawell Circuit was extending its borders in Herefordshire and Monmouthshire, Cwm Circuit was also laudably employed in missionary efforts in the same counties. In the town of Bromyard, in the east of Herefordshire, and at many villages and hamlets around, the missionaries belonging to this circuit labored with zeal and diligence, in the midst of much opposition and despite many hardships and privations. They, however, met with a measure of success. A room was taken on rent in Bromyard and opened for worship on 4 August 1833, and a new chapel was opened there about two years afterwards. But the societies in this part of the country did not flourish like those in the upper part, several untoward circumstances having occurred which retarded their progress.[31]

Thomas Kington became the superintendent of this group of the United Brethren, which also included a standing committee. By 1840, there were forty-seven male and female preachers (with eight on trial) who attended to the spiritual needs of people in forty-two places of worship.[32] The chief preachers met once every three months to arrange the dates and places for preaching on a preachers’ plan for the next quarter. As with the Primitive Methodists, lay preaching was the main practice of the United Brethren. Some preached several times on Sunday and on most evenings of the week, whereas others with more labor commitments preached only on Sunday.[33] They used much of the organization of the Primitive Methodists, including a preachers’ plan that was almost identical.

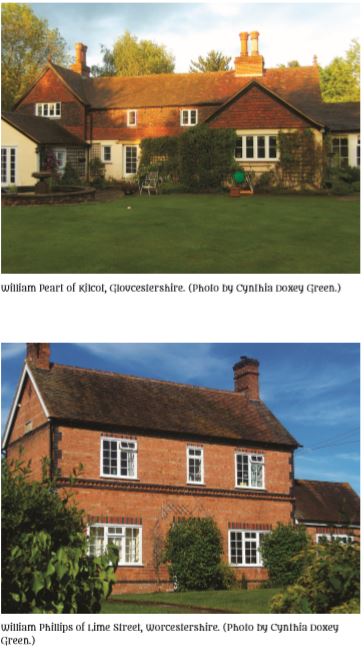

By 1840, the United Brethren group numbered around six hundred people; they had a chapel at Gadfield Elm, along with many houses and barns licensed for preaching in the Three Counties.[34] They had formed into two circuits (or conferences), called Froom’s Hill and Gatfield Elm.[35] We found several of their homes by looking for the names of the United Brethren on the licenses for preaching. We then located these names and their properties on the tithe survey maps in the appropriate county record office. Once we had found the places on the 1¼-inch to 1-mile scale Ordnance Survey maps, we drove to the homes and barns and took photographs. More details of this process are noted in the Appendix. Obviously, some of the homes have been modernized, but the locations are accurate. A sample of some of those homes and barns follows. Other photographs appear to illustrate stories in later chapters.

Little is known of the doctrine and practices of the United Brethren, but preaching was interspersed with individual praying, which so affected the congregation that several might be heard praying simultaneously. The group encouraged families and individuals to pray vocally. Sometimes, as people listened to the preachers, members of the congregation—frequently young females—“would fall down on the floor in a fit of noisy desperation concerning their supposed awful condition of sins committed and unforgiven.”[36] After the preacher had exhorted the individual to believe and the person had agreed to do so, “the young person would spring up and dance around in a noisy fit of ecstasy.”[37] Regarding the beliefs of the United Brethren, Job Smith, who attended their meetings, observed, “There was, beyond all controversy, a deeply devout feeling, devoid of all ostentation, intense opposition to all forms of pride, profanity and every form of immorality.”[38]

These were the social, political, economic, and religious conditions that existed in Britain when Wilford Woodruff and his fellow missionaries arrived in 1840. Just as Sidney Rigdon and his group had their minds in readiness to receive the message of the restored gospel when Parley P. Pratt and his companions arrived in the Kirtland area of the United States, a people were prepared for the same message when Wilford Woodruff and other Latter-day Saint missionaries arrived in the Three Counties area of England. Itinerant and outdoor preaching, shared personal testimonies, a lay ministry and lay member participation, and acceptance of dreams and visions as manifestations of divine intervention were all part of their religious experience. Hence, they would not have been shocked when the missionaries used these methods as they preached the message of the restored gospel.

Notes

[1] Richard S. Van Wagoner, Sidney Rigdon: A Portrait of Religious Excess (Salt Lake City: Signature Books, 1994), 29, 31.

[2] J. F. C. Harrison, ed., Society and Politics in England, 1780–1960: A Selection of Readings and Comments (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), 4.

[3] Harrison, Society and Politics, 22–23.

[4] Samuel Coulson, “Child Labor in the Factories,” in Society and Politics in England, 1780–1960: A Selection of Readings and Comments, ed. J. F. C. Harrison (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), 150–52.

[5] Harrison, Society and Politics, 124.

[6] The Reading Mercury, 11 May 1795, “The Speenhamland System,” in Society and Politics in England, 43.

[7] His Majesty’s Commissioners, “The 1834 Poor Law Report,” in Society and Politics in England, 148.

[8] Hugh McCleod, Religion and the Working Class in Nineteenth-Century Britain (London: Macmillan, 1984), 18.

[9] Joseph Arch, “Rich and Poor in the Parish Church,” in Society and Politics in England, 175.

[10] McCleod, Religion and the Working Class, 18.

[11] Alan D. Gilbert, Religion and Society in Industrial England: Church, Chapel and Social Change, 1740–1914 (New York: Longman, 1976), 34.

[12] Gilbert, Religion and Society, 66.

[13] Gilbert, Religion and Society, 19–21.

[14] Gilbert, Religion and Society, 33, 35.

[15] Gilbert, Religion and Society, 30–31.

[16] Geoffrey Milburn, Primitive Methodism (Peterborough: Epworth Press, 2002), 3, 5.

[17] Milburn, Primitive Methodism, 3, 5, 11.

[18] Milburn, Primitive Methodism, 7.

[19] McCleod, Religion and the Working Class, 26.

[20] McCleod, Religion and the Working Class, 29.

[21] Julia Stewart Werner, The Primitive Methodist Connexion: Its Background and Early History (Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1984), 175–76.

[22] Werner, The Primitive Methodist Connexion, 174.

[23] McCleod, Religion and the Working Class, 27.

[24] Werner, The Primitive Methodist Connexion, 185.

[25] Werner, The Primitive Methodist Connexion, 158.

[26] Henry Woodcock, “Piety among the Peasantry,” in Society and Politics in England, 187–88.

[27] “Memoir of Sarah Harding (Of Frooms Hill, Herefordshire, Cwm Circuit),” Primitive Methodist Magazine 3 (1833): 64–65.

[28] Job Smith, “The United Brethren,” Improvement Era, May 1910, 821.

[29] Milburn, Primitive Methodism, 28.

[30] “An Ecclesiastical History, chapter 80, The Fifteenth Century, p. 172–74,” Primitive Methodist Magazine 5 (May 1835): 174.

[31] John Petty, The History of the Primitive Methodist Connexion from Its Origin to the Conference of 1859 (London: Danks, 1860), 298.

[32] “United Brethren Preachers’ Pan of the Frooms Hill Circuit, 1840,” 248.6 U58p 1840, Church History Library, Salt Lake City.

[33] Job Smith, “The United Brethren,” Improvement Era, July 1910, 820.

[34] Wilford Woodruff, Leaves from My Journal (Salt Lake City: Juvenile Instructor Office, 1881; republished by LDS Archive Publishers, Grantsville, UT, 1997), 126–27.

[35] Smith, “The United Brethren,” 819.

[36] Smith, “The United Brethren,” 820–821.

[37] Smith, “The United Brethren,” 821.

[38] Smith, “The United Brethren,” 821.