Wilford Wood’s Twentieth-Century Treks East: A Visionary’s Mission to Preserve Historic Sites

J. B. Haws

J.B. Haws, “Wilford Wood's Twentieth-Century Treks East: A Visionary's Mission to Preserve Historic Sites,” in Far Away in the West: Reflections on the Mormon Pioneer Trail, edited by Scott C. Esplin, Richard E. Bennett, Susan Easton Black, and Craig K. Manscill (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 251–76.

J. B. Haws was an assistant professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was written.

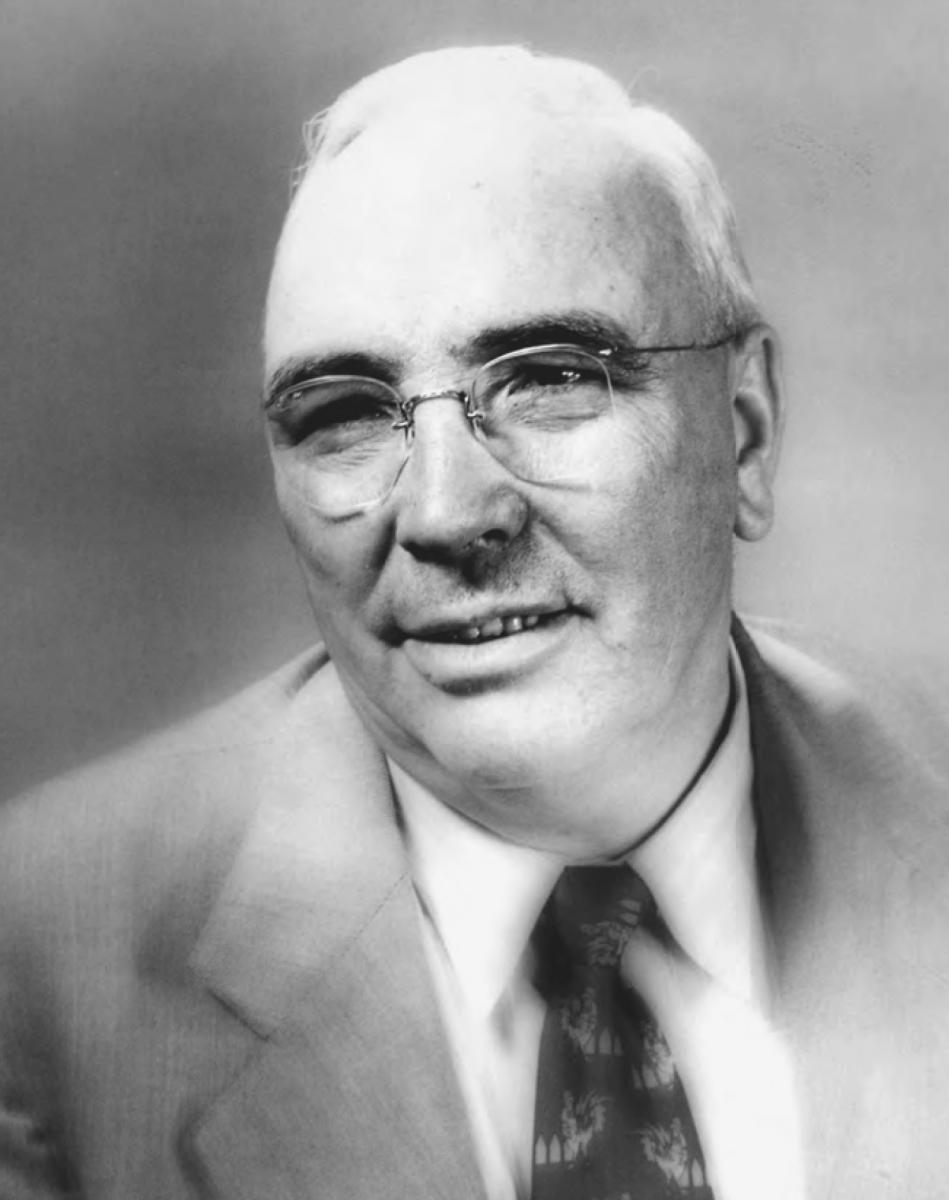

Wilford C. Wood. Photograph taken ca. 1950s. Courtesy of the Wilford C. Wood family.

Wilford C. Wood. Photograph taken ca. 1950s. Courtesy of the Wilford C. Wood family.

Anyone who has looked into The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints’ acquisition of important historic sites has come across Wilford Wood’s name. In some ways, he is now more of a legend than a man. It’s as if he is in the background of every historic photograph, as if he had a cameo appearance in every important recreation of Mormon history in the middle of the twentieth century. Church leaders such as David O. McKay, Gordon B. Hinckley, and Thomas S. Monson have praise him highly. But there are also some aspects of his character and disposition—and, it should be noted, most of these aspects were self-identified—that give observers pause, that seem quirky, to say the least. This paper is unabashed in its desire to pay tribute to him and his contributions to the memorialization and preservation of Latter-day Saint history. So how do readers deal with the quirks?

The hope here is that a measure of the justice due Wilford Wood and his legacy will come through in this one assertion: Wilford Wood was a visionary. The Church currently owns and operates dozens of historic sites across the United States, and informal pilgrimages to those sites have become almost a hallmark of the faith—but it wasn’t always so. Wilford Wood was ahead of his time. He saw and pursued opportunities related to Mormon historic sites that others did not yet recognize or appreciate—and this of his own independent initiative. Latter-day Saints and other interested historians owe much to his foresight and tenacity. However, being ahead of one’s time also means that visionaries have much convincing to do, often by sheer force of personality. And Wilford Wood had force of personality. Importantly, his singular focus seemed to well up both from his native disposition and his Mormon faith. Both impulses need to be considered in this attempt to understand a complex and committed man whose contributions to Mormon history merit the recognition that has come to him. Yet his singular focus also seemed to obscure for him pitfalls that occasionally proved to be difficult for him and his church—pitfalls that also required some sensitive extrications. His story thus has something to say, as an important side note, about a particularly (and paradoxically) Mormon mindset about visionaries. It’s a story that weaves in and out of old Nauvoo, and it’s the story of a man who enthusiastically encouraged a number of courses that the Church is still pursuing today.[1]

A Consummate Salesman

The life of Wilford Wood calls for much more biographical work.[2] He deserves a full portrait, but for now a pencil sketch will have to do. For those familiar with Davis County, Utah, Wilford Wood’s progenitors are the “Woods” in Woods Cross, Utah (a few miles north of Salt Lake City). Born into a Latter-day Saint family in 1893, he grew up on farmland in the hills overlooking the Great Salt Lake.

He proselytized for the Church in the Northern States Mission (which covered much of the midwestern United States) from 1915–18. The young missionary earned the honorific title of “Book of Mormon Wood” from his comrades for his effectiveness in distributing copies of the Book of Mormon.[3] He seemed to be the consummate salesman in the best sense of that word. When he believed in what he was doing, his persistence and charisma were forces to be reckoned with and he believed in what he was doing as he spread the message of Joseph Smith’s life work. Wilford Wood’s first visits to Carthage and Nauvoo as a young missionary were deeply formative. He vowed to do what he could throughout his life to honor the memory of the Church’s founding prophet.[4]

Wilford Wood’s success in his chosen occupation as a furrier made that pursuit financially viable. His fur business also facilitated contact with clients like Mormon Apostle David O. McKay, who in the 1930s, along with many other Utah customers, was paying Wood to store furs during the summer in his hillside vault. A 1931 article in the Improvement Era called Wilford Wood the “leading pelt buyer in the five states of Utah, Nevada, Arizona, Idaho, and Wyoming.” He had discovered, the article said, that his so-called “waste land”—his thirty acres of inherited property on a rocky hillside—was as “fine for fur farms” as it was for grazing sheep. His land also contained a grape vineyard, and Wilford Wood fed the fruit to his foxes, which he said gave the animals a superior fur. So confident was he in the quality of the furs that he raised and processed that he fought the rating that Utah furs received at the time. St. Louis fur graders had lumped Utah furs with lower-quality “Southern Stuff,” and this grade hurt the furs’ potential pricing. In a move that seemed to capture the essence of Wilford Wood, he “asked the graders to pick out some of their best [musk]rat skins and he would select the best of his and they wouldn’t be able to tell which was which. And they couldn’t.” He repeated a similar challenge in New York and thus added as much as “twenty percent” to the value of his Utah-grown furs.[5]

With that telling and very representative snapshot of Wilford Wood as an energetic businessman in hand, it is not difficult to imagine him traversing the country—almost always by car—on his way to and from East Coast shows and conventions, directing that same type of vocational energy to his true avocation, Mormon history. (A sample of his travel schedule: in a one-year period, 1952–53, he reported that he “crossed the plains” nineteen times.)[6]

He first began by acquiring Mormon documents and artifacts.[7] Wood recorded many of his stops in the cover pages of a first-edition 1830 Book of Mormon, even though such a practice might make a collector today cringe. He had acquired the book from Sister Rebecca Bean, one of the Church’s pioneering missionaries in Palmyra, New York, in a trade for a fur. He also collected in those cover pages the autographs of the Church’s presiding elders.[8] Wood’s frequent appearances at significant Mormon stops across the country, as well as his inquiries about Mormon memorabilia, made his face fortuitously familiar, and these cross-country contacts paid off in early 1937. The story behind Wilford Wood’s first real-estate purchase—a parcel of the Nauvoo Temple lot—is worth repeating here for what it says about Wilford Wood and his dogged sense of mission.

In February 1937, a telegram came to Wood from Nauvoo, alerting him that the Bank of Nauvoo was planning to auction off a portion of the city lot where the Mormons’ Nauvoo Temple once stood, a parcel that the bank owned by default. Wood’s interest in the property was well known in Nauvoo. Wood also knew well that this announced sale came with some built-in difficulties. Twice before, the bank had tried to auction off the lot, but because the bids never reached a level that satisfied the bank, it had protected its own interests and bought back the parcel. Still, Wilford Wood alerted the First Presidency about the telegraphed announcement, and the First Presidency authorized him to act as the Church’s agent in bidding up to $1,000. The bank had announced that the bidding would start at $1,000, but undeterred, Wilford Wood made the two-day drive from Utah to Nauvoo.

His negotiations with bank officials on the day before the auction did not start well. The bank’s managers insisted that the land would sell for a price in the $1,000 to $1,500 range—and the possibility that the bank would once again step in to end the auction added to the uncertainty. In the thick of these frustrations, Wood recounted that he felt inspired to ask a penetrating question, which opened what was to him a miraculous resolution of the impasse: “Are you going to try to make us pay an exorbitant price for the blood of the martyred Prophet,” he pled, “when you know this property rightfully belongs to the Mormon people?” The bank officials reconsidered; they agreed on the price of $900, and they honored that commitment at the auction the following day when they instructed their agents to refrain from bidding. Wilford Wood told the Improvement Era something that he would repeat again and again as he retold the story: “I felt the spirit of the Prophet Joseph in that room.”[9]

A Flood of Acquisitions

This opened a comparative flood of real-estate acquisitions—fifteen over the next nineteen years. As Kenneth Mays aptly put it in a 2009 tribute to Wilford Wood, “When Wilford C. Wood was born in 1893, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints did not hold title to a single site where a revelation in the Doctrine and Covenants was received or recorded. However, as a result of his years of vision and service, the Church eventually came to own the property or location where forty-eight sections of the Doctrine and Covenants were received.”[10] Wood bought a number of sites connected with the successes and setbacks of Joseph Smith and his followers: Liberty Jail (Missouri), Adam-ondi-Ahman (Missouri), the John Johnson home (Hiram, Ohio), the Isaac Hale and Joseph Smith lots in Harmony (now Oakland, Pennsylvania), the Times and Seasons building and John Taylor home (Nauvoo, Illinois), and the Newel K. Whitney Store (Kirtland, Ohio). Wood’s February 1937 experience in Nauvoo was thus just a small foretaste of what was to come.

That first temple parcel purchase came at a time of increasing interest in Church historic sites. The same April 1937 issue of the Improvement Era that reported the Nauvoo Temple block purchase also highlighted monuments at the Mormon pioneer way stations of Winter Quarters and Mount Pisgah. The Carthage Jail, purchased by the Church in 1903, was restored in 1938.[11] Joseph F. Smith, President of the Church in the first two decades of the twentieth century, had approved efforts to acquire a limited number of sites associated with the foundational events in his progenitors’ lives: Joseph Smith’s birthplace in Sharon, Vermont; the Smith family farm (and Hill Cumorah) near Palmyra, New York; and the Carthage Jail.[12] Still, in the 1930s, Wilford Wood seemed more eager than his contemporaries to expand those types of historic holdings, especially since many Mormon leaders during those Great Depression years might have wondered about the wisdom in expending funds for property far removed from Mormon population centers. Most of Wood’s subsequent purchases he therefore undertook on his own—with the Church, in turn, willing (at least in most cases) to buy the properties from him after he had purchased them.

There is a gold mine of a source about Wilford Wood in the annals of Brigham Young University. He gave a five-day series of lectures at the university’s 1953 Leadership Week called “Exhibits of Mormonism,” and those lectures were recorded and transcribed.[13] Reading those transcripts, one can almost hear him speaking. Even in reading them, the pace is fast—and changes in direction often come midsentence. He was sometimes painfully blunt, true to his reputation, in recounting his experiences and his philosophy about Church events (and Church leadership).[14] He also revealed a heartfelt intensity about his experiences and drive.

Wilford Wood told his audiences at one Leadership Week lecture that just two months after the first temple lot purchase, a party of property holders contacted him with the offer of another section of the Nauvoo Temple lot. An aging opera house stood on this parcel. Wood related that President David O. McKay (then a counselor to Church President Heber J. Grant) advised him, “Don’t buy any more property. A lot of the brethren [Church General Authorities] don’t know what we want to do with the Nauvoo property.” Excitement over historic site preservation among Church leaders was, to say the least, not universal. But someone else’s encouragement trumped President McKay’s cautions. Wilford Wood’s wife told him (again, from Wood’s own account), “Why, you are foolish for not buying that.” Wood told his audience, “President McKay said, ‘Always remember your wife’s judgment is better than yours.’ So I had a good excuse, and I went back [to Nauvoo].”[15]

When he arrived, he met with a banker in Nauvoo—and revealed that he understood just how precarious his position was. “I represent the Church,” Wood told the banker, “but the money I am going to spend is neither the Church’s nor yours. . . . If I buy this property, and the Church does not want it, you are paying half and I am paying half.”[16]

In the end, President Grant did buy the property from Wilford Wood for the $1,100 Wood had paid, and in a twist of fate that Wilford saw as providential, the opera house burned down within a matter of months. Because the building was insured for $1,500, Wood celebrated the fact that this purchase actually made the Church a $400 profit: “President Grant received one quarter of the whole Temple Block, and four hundred dollars in cash. That gave me a better mark in credit for purchasing for the Church than any other start in that work.”[17]

These early successes seemed only to stoke the fires in the belly of this locomotive. When a woman in California initially refused to consider what Wood thought was a reasonable price for “valuable pieces of goods she had that the Church wanted” (presumably a set of uncut printed sheets of the 1830 Book of Mormon), he turned to showing furs to the woman instead. When she picked out the one she wanted, he apologized that the fur in question was not for sale. “Anything’s for sale,” she apparently replied—and the deal for the Book of Mormon sheets was struck soon thereafter.[18]

He described taking watermelons to the home of George Colwell, who owned what had been the properties of Joseph Smith and his in-laws in Harmony (now Oakland), Pennsylvania. “It had rained outside,” Wood said. “When time came to go to bed we hadn’t left. My two daughters had gone with the rest of the family. . . . I would have been there yet if he had not said yes, because I was told to buy that property.” It is not clear from the account if Wilford meant that he was “told to buy that property” by Church superiors or by what he felt was divine inspiration. Regardless, what does seem clear is that he felt the sale was remarkable, since he reported that “the manager of the railroad [in Oakland, Pennsylvania] took me down to [Colwell’s] home, and said, ‘Mr. Wood, I fear you are wasting your time. George Cowald [Colwell] has never sold a piece of property in all his life.’”[19]

In connection with another purchase, Wilford told two General Authorities that he had found a “way of buying these things” that he would “keep to.” He advised, “[One] must not say a good thing about [the] building” that one is pursuing. He had found success with that approach by pointing out to a building’s seller “a crack over the door before we got inside. To make a long story short, this fellow threw up his hands and said, ‘I do not want to own this property. Let’s get out of here. I’m beginning to think this building will fall down and I’ll have to pay for it.’”[20]

He was a resourceful negotiator, to be sure. And the results he achieved, if not always the means, prompted President McKay to write to Wilford Wood in 1944 and say, “Your narration of the difficulties you encounter in obtaining your objectives [specifically the document purchase of the court proceedings related to the deaths of Joseph and Hyrum Smith, and then the real-estate purchase of Adam-ondi-Ahman, Missouri], led me to silently exclaim: Persistency, thou art a jewel, and your name is Wilford Wood! I congratulate you upon your success in overcoming obstacles, and also upon your achievement.”[21]

Persistence and Providence

But Wilford Wood readily attributed his successful real-estate purchases to a source beyond his own tenacity or salesmanship. He saw in his efforts the hand of providence, and over and over again he expressed his personal feelings that he was guided by heaven. He repeated often a blessing that he said came at the hands of President McKay: that if he would not seek for personal gain or riches, his first impression would be right and he would not be deceived.[22]

He saw this operative, for example, in the dreams and visions that marked his career. One reported example came soon after Wood had negotiated for the Reimbold property in Nauvoo, which would become the Church’s spot for a Bureau of Information on the Temple Block. (This was a March 1951 purchase for $16,000.) He had a vision of the possible negative reaction to the Mormons’ return to Nauvoo—particularly the return of Mormon missionaries, since the plan for this new site was to have it staffed by missionaries. He said he saw, when he was asleep “or perhaps . . . awake[,] . . . it doesn’t matter,” housewives running out their back doors and telling each other, “The Mormons are coming.” He felt inspired to host a huge chicken dinner, and he employed the help of Nauvoo’s mayor to do so. Wood invited Nauvoo’s Catholic Monsignor, who had initially been cool to the Church, to offer grace. “As Right Reverend Monsignor said Grace and prayed,” Wood remembered, “the darkness went out and the light came on.”[23]

Other examples of divine help were less elegantly described—and these descriptions can admittedly grate on current sensibilities, even if they were told tongue-in-cheek. The elderly woman who was selling the Reimbold property had also been approached by the presiding bishopric of the Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS). That meeting had come while Wood was in Salt Lake discussing the $16,000 price tag with President McKay. After getting President McKay’s approval, Wood said he hurried back to Nauvoo. In his words:

It was a cold winter day when I went in there. She said to me, “It’s my birthday.” I said, “Yes, are you going to sell your home?” “Well,” she said, “Let me tell you, the full Bishopric of the Reorganized Church have been here. They have asked, ‘If we pay you as much as the Mormons will pay, will you sell to us?’” I asked her, “What did you tell them?” She said, “I couldn’t talk.” Well anytime a woman can’t talk, there’s either a divine power there, or something has gone wrong with her. So I accepted it, that providence . . . then I said, “Are you going to sell to me?” She said, “Yes.” I said, “Put your name down here.”[24]

What should not be missed in all of this, even with bits of his sometimes questionable trademark brand of humor sprinkled in, is that Wilford Wood seemed absolutely sincere about these manifestations of the hand of providence in moving forward this work that he saw as essential. And even if his was an extreme representation of faith that not all of his co-religionists would have fully endorsed, still he seemed to draw on much that is at the heart of Mormonism. Continuing—and even personal—revelation is central to Mormonism, as is a desire to evangelize and spread the gospel message. Wood felt that he was impelled by the first in order to accomplish the second. When, for example, he intended to place a placard designating the site where John the Baptist met Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery and gave them priesthood authority in Harmony, Pennsylvania, Wood said that President George Albert Smith told him, in 1946, “Wilford, you will be guided to the spot and know where to place this sign.”[25] Early in his career, Wilford repeatedly related what he described as inspiration of guidance; by the mid-1950s, he began to recount visions that were longer and more involved.

He reported, for example, that he had a vision of the Prophet Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery in 1955—they appeared on the banks of the Susquehanna River in Pennsylvania to explain priesthood duties.[26] Wood also reported in 1960 that he saw a vision of New Testament Apostles Peter, James, and John conferring greater priesthood on Joseph Smith and Oliver Cowdery, and he even recorded the words of the ordination prayer, together with a description of Joseph Smith’s reflective look when, in that vision, he told Wood that he (Joseph Smith) could not then have imagined that his martyrdom would come fifteen years to the day after that Melchizedek Priesthood ordination.[27]

A Picture of a Mormon Paradox: “Authoritarianism and Individualism”

It seems important to note here that because spiritual communication is, to many, a sacred, personal province, there is much to commend the restraint that several observers have exercised as they have considered Wilford Wood’s autobiographical reports.[28] President David O. McKay’s brother, Robert, told Wood that after he (Robert) had presented to President McKay a report of some of Wilford Wood’s spiritual experiences in 1963, “there was little time for a discussion of the entries or of your experiences pertaining thereto, but the President did say, pointing to the letters and photographs, that what you have is sacred and should be held so, always. He further stated that what you have experienced no man can disprove.”[29] What this restraint seems to speak to, at least in part, is a recognition that the possibility of personal revelation—communion with the divine—is a treasured component of Mormon religious life, even if such communion is reported to have occurred (as in Wilford Wood’s case) in unexpected or uncommon ways.

This paper aims to partake of that same spirit, that same reticence in trying to evaluate what Wood may or may not have experienced. Still, two of his other reported visions do merit further discussion here because of what those visions prompted him to do—and thus they come to bear directly on two of his most instructive, and also most controversial, purchases. What these experiences later in Wilford Wood’s life also reveal is the sometimes tricky negotiation in Mormonism of a paradox that astute Mormon cultural historian Terryl Givens aptly calls the “polarity of authoritarianism and individualism.”[30] This is the interplay in Mormonism between an individual’s right to personal revelation and the “prophetic prerogatives” invested in the Church’s presiding elders to make decisions for the Church as a body.[31] For Latter-day Saints who see this paradox as being productive and counterbalancing instead of being paralyzing, Wood might offer a representative example.[32]

In 1954, Arline Mulch owned the Mormon-built Masonic Hall in Nauvoo. It had been in her family for years. Wood had developed a friendship with Arline Mulch’s father—and by all reports, her father treasured the Masonic Hall. Charles Mulch had evidently told Arline to hold onto it as long as she could, to make it the last property she sold. Arline’s father died in 1949, and Wood heavily pursued the Masonic Hall. In his own report, he said that after two days of repeated negotiations and ten trips from Nauvoo to Keokuk, Iowa, to present possible contracts to Arline, she finally agreed to sell the building and approximately twelve acres for $10,750. Then Wood and others discovered in the building’s cornerstone a copper-box time capsule with important Masonic documents as well as documents from 1840s Nauvoo. Wood was thrilled to present the documents to President McKay (in the Salt Lake Temple, no less). He apparently began spreading the word that both President McKay and Joseph Fielding Smith saw in the documents indications that the Millennium—the triumphal return of Jesus Christ—was only fourty years away. President McKay explicitly stated that he had not taught such things.[33]

But a more difficult controversy arose as Arline Mulch repeatedly wrote to Wilford Wood, literally begging him to nullify the contract and return the property. Her pleas were painfully pathetic, and they started coming within a few days of the sale:

I am very ill and crazed with grief over what I have done. . . . You represent a wonderful Church and a great Church and a great people and I am only a lone woman begging for forgiveness for my great mistake. . . . You are a husband and a father and as I have neither, please be kind to me. . . . I hope and pray that with your generous heart you will see how I feel and give me the help that I need. The whole thing was wrong from the beginning, price and all.[34]

Wood felt the sale was transacted legally, and he thought that the publicity and attention from the sale—and from placing a new time capsule—would placate Arline Mulch. He was wrong. Arline Mulch contracted the services of a lawyer, and word soon spread to Nauvoo-area media outlets that Wood had used high-pressure sales tactics; he had apparently told Arline the night before the sale was finalized that he had seen in vision her deceased father, who had approved the sale. Her lawyer was blunt with Church Apostle Adam Bennion:

Your organization is willing to accept the benefits of these labors and have not only done that but have indicated that you will permit him to continue to prey on other people with his high pressure methods and treat them in the same manner he has treated Miss Mulch. . . . We feel as though your organization, if it continues to use the same methods in this case, should have its activities called to the attention of the world at large. I do not wish to be indelicate [but] the activities of this kind by the Mormon Church in this area will certainly be news for our local radio station, our Des Moines Register representative and our Chicago Tribune representative.”[35]

The Church returned the property. Wilford Wood wrote to another Church leader, “It is the most ridiculous thing to think of to have [Church Apostles Adam S.] Bennion and [George Q.] Morris both say that it is because of my behavior and actions in getting this property that was the cause of the law suit.”[36]

Wood may have been disappointed and angry over the Masonic Hall setback, but he was not deterred in his work. The next year, in 1956, he negotiated the purchase of the John Johnson farm in Hiram, Ohio, a place where Joseph and Emma Smith had lived for an eventful year in the early 1830s. Wood related that after a day of fruitless and frustrating negotiations, he was awakened in the middle of the night by a visit/

But Wood had pushed the contract through before Bishop Thorpe Isaacson of the Church’s Presiding Bishopric had arrived in Hiram. Wood had made the trip by car, and he was upset that he had a few days to wait before Bishop Isaacson would arrive by plane, so Wood apparently proceeded without him. Bishop Isaacson was not pleased when he found out about Wood’s presumptuous negotiations, but after further investigation of the arrangement, by Wood’s report, Bishop Isaacson conceded that Wilford “had been guided.”[38]

To Wood, the most important part of the experience was that Joseph Smith, in this vision, had also shown Wood the spot where he had been tarred and feathered by an angry mob in 1832 and had asked Wood that the spot be appropriately memorialized. Thus Wood planted a border of trees around the thousand-foot-square parcel and then reported to President McKay that the smile on the Prophet Joseph Smith’s face (as seen in a vision) was sublime.[39]

One year previous to this purchase, in early 1955, the Church’s First Presidency had privately worried about Wood’s activities—and then gently acted accordingly. He had been entrusted with a broad range of responsibilities for historic sites. For several years in the late 1940s and early 1950s, Wood had been the one to seek out what were called “Melchizedek Priesthood” missionaries (essentially retired couples) to staff the historic sites as hosts and guides. In 1955, his role in calling those missionaries was discontinued, and the First Presidency expressed a hearty thanks for his work. Historic sites missionaries were subsequently called through the same centralized channels as other Church missionaries.[40]

Wilford Wood continued to have in his charge the affairs at the John Johnson farm in Hiram, Ohio, for another decade. But that assignment notwithstanding, it was apparent that Wood lamented the change in his authority over the historic sites missionaries. This was a delicate issue, and he responded sometimes curtly to those who he felt were undermining his contribution, especially when it had been, as he pointed out, such a self-sacrificing one. He wrote this to Bishop Isaacson in February 1955 as the changes to the missionary assignment process were being considered: “I wish that you would do something about my assignment on this committee. . . . If I do not have the appointment to take care of these missionaries or to be field man or something of responsibility, I am of no value. Oil and water do not mix. [General Authorities on the committee] have the authority and are of oil. I don’t want to just be the water to clean off their windshield when someone splashes mud on it so that their vision is clearer and then as soon as the windshield is clean, they go ahead as though I wasn’t even riding in the same car. Please Bishop, have me excused. . . . I won’t go away mad, I’ll just go away.”[41]

It seems important to remember that even after all of this apparent eccentricity, in 1957, President McKay wrote a note of thanks to Wilford Wood in response to a gift of birthday cantaloupes—and President McKay paid tribute to a diligent soul: “I knew at once that those best wishes came from one who has revived Nauvoo and its importance in church history as has no other man in the church. Affectionately, David O. McKay.”[42] That was the legacy that the president of the Church thought Wilford Wood deserved.

Beginning in these same years, though, Wood complained that the gap was widening between the path he had personally felt inspired to pursue and the path Church leaders chose to pursue. Wilford Wood was direct and public in his criticism of the actions of men such as Church Apostles Joseph Fielding Smith or George Q. Morris, men that he saw as destroyers of valuable historic sites. He strenuously disagreed with the Church projects aimed at renovation and beautification. This is what he told his 1953 Brigham Young University audience:

The hardest, most painful time of my life was when I received the word that Isaac Hale’s home was being torn down and there were two hundred acres of land there. The only excuse that came in was from President Joseph Fielding Smith, the Historian of the Church, that they needed it for a parking place and it was an unsightly thing. Now, . . . they could have found enough parking space on two hundred acres of land that the Church owned, but to say that a historical building is an unsightly thing, or to take any Pioneer’s work and think you can improve on it is a disgrace to you. You make your own life and living and monuments, and let them live because the Pioneers don’t need improvement. They finished their work, all they need to be is secured, protected, and preserved.[43]

He said to neighbor Ray C. Mills in February 1965:

I keep busy going back and forth to the historical properties and I now own not only the property where the Melchizedek Priesthood was restored in Susquehanna, Pennsylvania but last year I secured the Prophet’s home that he lived in while they built the Kirtland Temple in Kirtland, Ohio. These are my own personal property which I shall keep from the destroying hands of the new non-profit church committee that has no sense of value for the precious old originals that cannot be replaced. The non-profit organization spend the Churchs millions tearing down and putting something in their places that is modern and up to date for today but will be out of date in the tomorrows.[44]

Wood was a committed proponent of original condition, and a vocal opponent of the Church’s new committee-based approach to historic sites.[45]

Despite these expressions of disillusionment near the end of his life (he died in 1968), and thanks to the hindsight afforded by several subsequent decades, the irony is that Wilford Wood had by that time accomplished much of what he set out to do. His wife later said that “none of the things he collected were money-making ventures. In fact, he would never tell me what he paid for anything. He did it for one purpose—he loved the Prophet Joseph and the Book of Mormon, and he wanted to help preserve the things and places that had been a part of [Joseph’s] life.”[46] The resources that the Church by then did, and still does, devote to historic sites speaks to the impact of Wilford Wood’s persistent prodding about that preservation, even if Wood did not like the way those resources were allotted to reconstruct the sites themselves. Hundreds of thousands of visitors now tour places like historic Kirtland and Nauvoo, or Liberty Jail and the John Johnson home, every year. In 2002, the Church dedicated a rebuilt Nauvoo Temple on the same lot that Wilford Wood had begun to secure, piecemeal, sixty-five years earlier. And in 2011, the Church initiated an extensive restoration of the Joseph and Emma Smith home site in Harmony/

But one can also hear in Wilford Wood’s disillusionment the paradox that confronts many visionaries working within a hierarchical framework. In Mormonism, “all inspiration is not equal,” such that loyalty to the Church also required that Wilford Wood submit personal initiative to institutional authority.[48] Yet at least in the Masonic Hall case, this reining in of the visionary’s enthusiasm proved to produce eventually the very result Wilford Wood envisioned—and in that type of success, one catches a glimpse of a Mormon mindset that accepts that the tension between “faithfulness and freedom” can still work.[49] The postscript to the story of Arline Mulch is that when the Church returned the Masonic Hall, it asked for the right of first refusal for the property when she did decide to sell. A decade later, when Arline Mulch sold the property to the Church’s nonprofit Nauvoo Restoration, Inc. (this time the parcel was more than a hundred acres instead of just twelve), the Church paid $250,000.[50]

With all this said, it seems most fitting to end with a tribute to Wilford Wood’s foresight and force of personality. It also seems particularly fitting that the tribute comes from one of those in a position of institutional authority who supported, and sometimes carefully circumscribed, Wood’s drive. In a meeting at Wilford Wood’s home in late 1952, at a gathering of the historic sites missionaries, President McKay said this: “Represented here tonight, I think I am not exaggerating any when I give Wilford Wood full credit for these historical places, and he has vision of others. We will appreciate them later because as the years pass these historical places will become of more value and more interest.”[51]

Those who have since stood appreciatively on the historically rich properties that Wilford Wood acquired understand better the import of that prediction and share in that gratitude for zealous visionaries.

Notes

Thanks to Professor J. Taylor Hollist for his indispensable research and writing on Wilford Wood. This paper is indebted to Professor Hollist’s work.

[1] For an important work about Wilford Wood’s place in the larger Mormon movement to rebuild and memorialize Nauvoo, see Scott C. Esplin, “The Mormons Are Coming: The LDS Church’s Twentieth Century Return to Nauvoo,” Mormon Historical Studies 10, no. 2 (Fall 2009): 103–32; see especially pages 110–14. Esplin also considers changes in the philosophy of the Church’s leaders toward historic sites at Nauvoo.

[2] See two recent articles: Thomas S. Monson’s remarks at a 2009 banquet honoring the life and career of Wilford Wood, “Wilford C. Wood,” Mormon Historical Studies 10, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 146–53; and Kenneth R. Mays, “A Man of Vision and Determination: A Photographic Essay and Tribute to Wilford C. Wood,” Mormon Historical Studies 10, no. 1 (Spring 2009): 155–73. J. Taylor Hollist's fine research on Wilford Wood is housed as the Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, L. Tom Perry Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University, Provo, UT.

[3] Ariel Williams, introduction to Wilford Wood’s “Exhibits of Mormonism,” June 15, 1953, 1, bound in a collection of BYU Leadership Lectures under the title “The Immutable Laws of God,” L. Tom Perry Special Collections. Dr. Williams was Wilford Wood’s companion in southern Indiana, and he reported that Wilford Wood distributed/

[4] Williams, in Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” 1.

[5] Frank R. Arnold, “Making Economic Fur Fly,” Improvement Era, May 1931, 396–97.

[6] Williams, in Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” 1.

[7] For example, he “acquired the death masks (casts) of Joseph and Hyrum Smith. George Cannon (1794–1844) is reported to have made the masks at the time the bodies of the martyrs were being prepared for burial.” Mays, “A Man of Vision and Determination,” 159.

[8] Photocopies of the front pages of that 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon are included in the unnumbered introductory pages of Wilford C. Wood, Joseph Smith Begins His Work (Salt Lake City: Wilford C. Wood, 1958). This book is Wood’s self-published reprint of the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon.

[9] M. C. J. (Marba C. Josephson),“Church Acquires Nauvoo Temple Site,” Improvement Era, April 1937, 227.

[10] Mays, “A Man of Vision and Determination,” 155.

[11] The Winter Quarters monument was new in 1936; the Mount Pisgah memorial was a refurbishment of a long-held Church property.

[12] See T. Jeffery Cottle and Richard Neitzel Holzapfel, “Historical Sites,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, ed. Arnold K. Garr, Donald Q. Cannon, and Richard O. Cowan (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2000), 502–4; Kenneth W. Godfrey, “Carthage Jail,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 192–93; Rex C. Reeve Jr., “Hill Cumorah,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 481–82; Arnold K. Garr, “Sharon, Vermont,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 1094–95; David Kenison, “Smith, George Albert,” in Encyclopedia of Latter-day Saint History, 1115–17.

[13] See Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism.”

[14] See Truman Madsen’s response to a 1961 seminar presentation that Wilford Wood made at BYU: “Three comments on Brother Wood’s presentation. He is delightfully frank, even brutal, in his presentation, but he made—as often happens—three rather serious errors.” 1961 Seminar on the Prophet Joseph Smith—February 18, 1961 (Provo, UT: Department of Publications and Adult Education and Extension Services, 1964), 83–84, L. Tom Perry Special Collections.

[15] Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” 4.

[16] Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” 4.

[17] Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” 5.

[18] Williams, in Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” 1. Although Dr. Williams does not specifically mention that the woman had the uncut sheets of the Book of Mormon, several details in the story seem to match Wilford Wood’s later retelling of obtaining those sheets from a woman in Santa Barbara. See Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” 6. Williams said, “One time he went to a woman that wouldn’t sell one of the valuable pieces of goods that the Church wanted. . . . She chose the fur, and he [Wood] obtained for the Church a very valuable piece of goods which he will show before this group”; emphasis added. The story of the Book of Mormon sheets came up in a later lecture, presumably as Wilford Wood was displaying the sheets.

[19] Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” 9. In these Leadership Week lectures, the seller’s name was transcribed variously as “George Cowald” and “George Kowall.” Compare LaMar C. Berrett, The Wilford C. Wood Collection: An Annotated Catalog of Documentary-Type Materials in the Wilford C. Wood Collection (Bountiful, UT: Wilford C. Wood Foundation, 1972), 1:5, for documentation of correspondence between Wilford Wood and George Colwell. The Harmony purchase was made in 1948. See also Mays, “A Man of Vision and Determination,” 165.

[20] Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” June 15, 1953, 10. It is difficult to know for certain which building he was describing.

[21] David O. McKay to Wilford Wood, March 20, 1944, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 6, Church History Library, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 3.

[22] See Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” June 16, 1953, 3; also Wilford Wood to David O. McKay, October 31, 1952, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 13, Church History Library, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 3.

[23] Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” June 15, 1953, 6.

[24] Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” June 15, 1953, 6. Wood also freely told his audience at Brigham Young University, “You know, I have a little book that I keep especially—that I write names in and when I go out to purchase things for the Church, and the people don’t sell them, I think they’re just against the Church, and so I write their names down and pray that they’ll die. As soon as they’re dead, I go back and get the things the Church wants. Now I don’t think there is any more wrong in having them die a little sooner than a little later. Then you can go and have the work done for them after they are dead—you can’t do a blooming thing with them when they’re alive. Besides that, I think there are people walking around that are a lot deader than those in the cemeteries.” Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” June 16, 1953, 5–6. The “work done for them after they are dead” presumably refers to the Latter-day Saint practice of performing saving rites, like baptism, by proxy for those who have died without performing those rites.

[25] J. Taylor Hollist, notes on Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 31, Church History Library, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 2.

[26] Wilford Wood to David O. McKay, December 23, 1955, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 27, Church History Library, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 2.

[27] Wilford Wood, September 30, 1960, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 2, Church History Library, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 2.

[28] See Karl Ricks Anderson to J. Taylor Hollist, March 25, 2007, Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 2. Anderson, a local Kirtland, Ohio, historian and longtime regional Mormon leader called Wood a great man and a visionary, and he wrote that he was not in a position to judge Wood’s visions.

[29] Robert R. McKay to Wilford Wood, January 30, 1963, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 2, Church History Library, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 2.

[30] Terry L. Givens, “Paradox and Discipleship,” Religious Educator 11, no. 1 (2010): 146.

[31] Givens, “Paradox and Discipleship,” 147.

[32] For additional insight into a Mormon approach to this paradox, see Dallin H. Oaks’s explanation of two channels of communication with God: “I refer to the relationship between obedience and knowledge. Members who have a testimony and who act upon it under the direction of their Church leaders are sometimes accused of blind obedience. . . . This is what our critics fail to understand. It puzzles them that we can be united in following our leaders and yet independent in knowing for ourselves. Perhaps the puzzle some feel can be explained by the reality that each of us has two different channels to God”—a “personal” channel and a “priesthood” or hierarchical channel. Dallin H. Oaks, “Testimony,” Ensign or Liahona, May 2008.

[33] I am indebted to the thorough research J. Taylor Hollist has done in connection with the sale of the Masonic Hall. See his retelling of this episode in an unpublished paper, J. Taylor Hollist, “Wilford C. Wood and the Nauvoo Masonic Hall,” Hollist Collection, MSS 6760. For documentation of correspondence between Charles Mulch, Latter-day Saint leaders, Arline Mulch, and Wilford Wood, see Berrett, Wilford C. Wood Collection, 77, 82, 91–92. On the question of the timing of the Millennium, see Taylor Hollist’s transcription of the David O. McKay Papers, August 17, 1954, journal entry, Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 5.

[34] Arline Mulch to Wilford Wood, April 26, 1954, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 10, Church History Library, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 5.

[35] Harold Martin to Adam S. Bennion, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 10, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 5.

[36] See, for example, Wilford Wood to Thorpe Isaacson, February 6, 1955, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 17, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 5.

[37] See Wilford Wood to President David O. McKay and Historical Committee, April 3, 1856, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 3, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 2.

[38] Wilford Wood to President David O. McKay, April 3, 1956, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 3, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 5: “Since coming home I received the report that you and others were unhappy because of my securing the property at Hiram, Ohio. . . . When Bishop Isaacson arrived by plane, I met him at the airport and went over all the details of what I had done. He was disappoint[ed] and wanted to go right back home and could hardly believe the blessings and manifestations which I had received to be true. I insisted that we go to the farm the next morning so that he could meet the people and know exactly what had been done. . . . Before the day was over, . . . he said, ‘I believe you have been guided.’” On Wilford’s impatience, see Wilford Wood to David O. McKay and Historical Committee, April 3, 1956: “Called the next morning and awoke Bishop Isaacson. He said he would not be in Cleveland until Monday night at 6:40 by plane. This meant we would be detained four days waiting for the Bishop. What an unnecessary waste of time.”

[39] Wilford Wood to David O. McKay, April 3, 1956. The Church has not elected to identify that site as such. For recent discussion about the location of the tarring and feathering by a Church-employed historian, see Mark L. Staker, “The Mobbing of Joseph Smith and Sidney Rigdon,” in Hearken, O Ye People: The Historical Setting of Joseph Smith’s Ohio Revelations (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2009), 345–74.

[40] See Wilford Wood to Stephen L. Richards, February 1, 1955, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 14, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 3. Wilford Wood responded to a request for a report of how he had organized the historic sites missionaries in the past. Compare also Stephen L. Richards’ concerns as expressed in Taylor Hollist’s transcription of the David O. McKay Papers, August 17, 1954, journal entry, Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 5: “President Richards wondered if the time has not come when Brother Wood might be given an honorable release from his mission, with appreciation for what he has done. We discussed various places of historic interest in the Church, some of which are not receiving the care they should have. It was agreed that President McKay would call the committee together.” For the decision, see First Presidency to Historical Properties Committee, March 11, 1955, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 14, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 3: “missionaries called to historic places [will] be recommended by bishops and stake presidents and interviewed by members of the General Authorities, as are other missionaries. Let the missionaries so called be subject to the jurisdiction and direction of the mission president in whose mission jurisdiction they are called to serve. The members of your Committee will be expected to have general oversight of the historic properties and the personnel serving in them. In order not to confuse the missionaries, however, your observations and suggestions should go to the personnel through the mission president under whose jurisdiction they labor. We desire to express appreciation for the long and valued services of Brother Wilford C. Wood, and for his abiding interest in places of historic interest to the Church. We are sure that without his interest and suggestions the whole matter would not have received the attention and development which has come to it.”

[41] Wilford Wood to Thorpe Isaacson, February 6, 1955.

[42] David O. McKay to Wilford Wood, August 25, 1957, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 7, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 3.

[43] Wood, “Exhibits of Mormonism,” June 18, 1953, 4.

[44] Cited in Hollist, “Wilford C. Wood and the Nauvoo Masonic Hall,” 9n24. The last historic property Wilford Wood purchased was the Newel K. Whitney store in Kirtland, Ohio. He acquired the store in December 1965, and the Wood family retained ownership of the property until 1979, when “Elder Gordon B. Hinckley formally received title to the . . . store” on behalf of the Church from Wilford Wood’s widow. See Mays, “A Man of Vision and Determination,” 171.

[45] Wilford Wood was also confident that the Church should return to the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon, and when the Prophet Joseph Smith had reportedly appeared to Wood, by Wood’s account Joseph read from the 1835 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants. Wilford Wood to David O. McKay, December 23, 1955: “After I had knelt in prayer and opened my eyes, the Prophet Joseph and Oliver stood before me and instructed me about the Holy Priesthood. The Prophet read the revelations he had received from the Doctrine and Covenants, 1835 edition, with the lectures on faith. The Prophet made it clear about the order of the Holy Priesthood. That complete records should be kept of every ordination.” See also Truman Madsen’s response to Wilford Wood’s 1961 presentation at the BYU seminar on Joseph Smith, 1961 Seminar on the Prophet Joseph Smith—February 18, 1961, 83–84. While the published record of that seminar includes the note that “Mr. Wood’s address”—unlike all other presentations at the seminar—“is not to be published here,” it seems likely, by inference, that one of the points Truman Madsen corrected at the end of the presentation was Wilford Wood’s emphasis on the preferred use of the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon: “[Wood] said, ‘Why would Moroni have taken the plates back if the Book of Mormon were not a perfect translation?’ Again there is a fallacy. In the Book of Mormon itself, the title page says, ‘If there are faults, they are the mistakes of men.’ We have not ever claimed that the Book of Mormon is an infallible book, in structure or content. We cannot. There are mistakes, there are grammatical errors even now, even though we have worked with them for all these years. . . . Remember further that the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon had in it not one grammatical break. . . . this telescoping, by the way, is exactly the kind of thing that would result from a translation. It is first-rank evidence that the Prophet did not, as his enemies claim, create the book, but simply translated it.”

[46] Janet Thomas, “Tracking the Mormon Relic,” This People 2, no. 3 (1981): 33.

[47] See Wilford C. Wood, Joseph Smith Begins His Work, 2 vols. (Salt Lake City: Wilford C. Wood, 1958–62). Volume 1 is Wood’s self-published reprint of the 1830 edition of the Book of Mormon; volume 2 is a reprint of the 1833 Book of Commandments and the 1835 Doctrine and Covenants. These same editions of scriptural books in the Joseph Smith Papers collection are accessible at josephsmithpapers.org/

[48] Givens, “Paradox and Discipleship,” 147.

[49] Givens, “Paradox and Discipleship,” 147.

[50] See Hollist, “Wilford C. Wood and the Nauvoo Masonic Hall,” 4.

[51] From a December 4, 1952 meeting, Collection of Church Historical Materials, MS 8617, microfilm 21, as transcribed in Hollist Collection, MSS 6760, box 1, folder 3.