Utah’s Role in Protecting the Mormon Trail during the Civil War

Kenneth L. Alford

Kenneth L. Alford, “Utah's Role in Protecting the Mormon Trail during the Civil War,” in Far Away in the West: Reflections on the Mormon Pioneer Trail, edited by Scott C. Esplin, Richard E. Bennett, Susan Easton Black, and Craig K. Manscill (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2015), 205–30.

Kenneth L. Alford was an associate professor of Church history and doctrine at Brigham Young University when this was written.

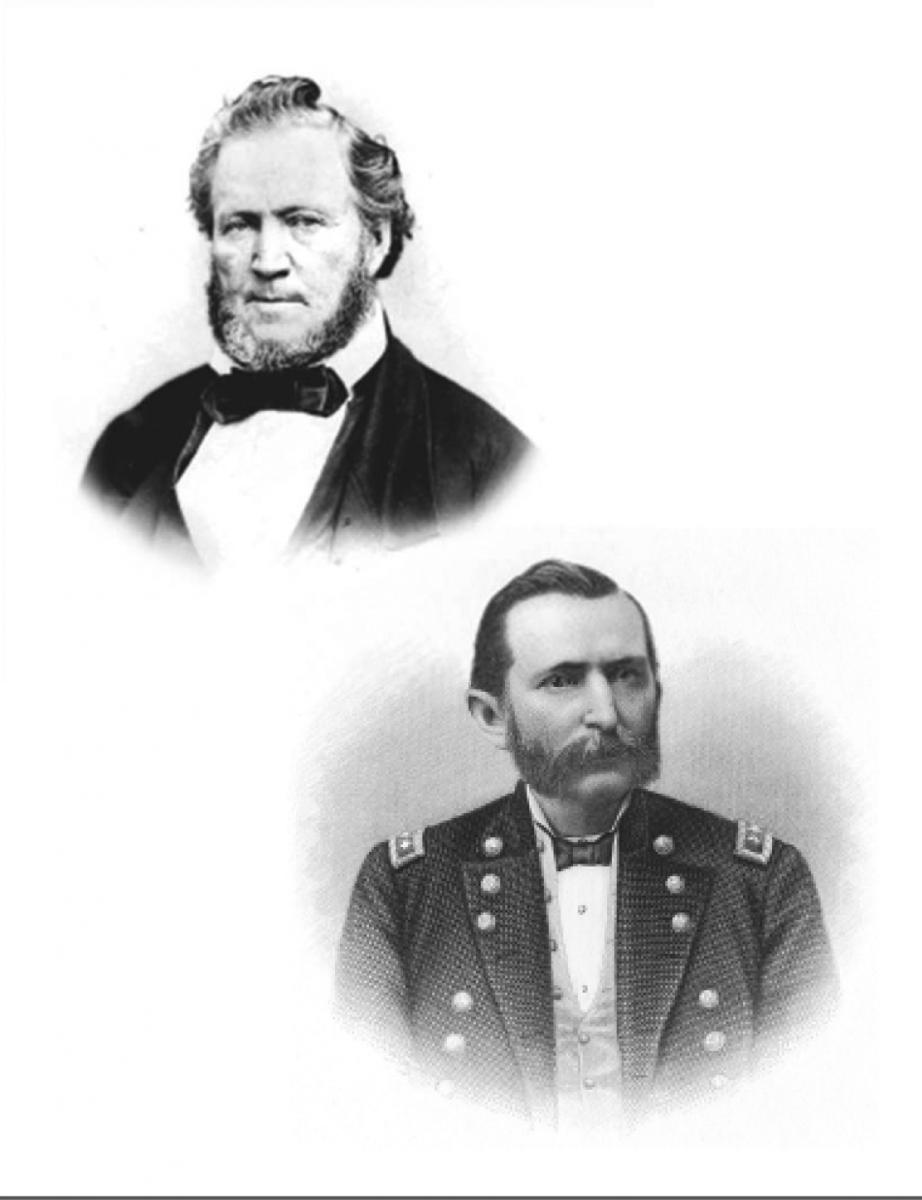

Photograph of Brigham Young by Charles Savage courtesy of the Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. Photograph of Patrick Edward Connor courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

Photograph of Brigham Young by Charles Savage courtesy of the Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University. Photograph of Patrick Edward Connor courtesy of the Utah State Historical Society.

The various overland trails—the Mormon Trail, Oregon Trail, Santa Fe Trail, and California Trail, for example—were used by hundreds of thousands of pioneers to emigrate west, and they figure prominently in American history. Stories from the mid-nineteenth-century Latter-day Saint hegira to the West are important in Mormon memory and folklore. Pioneer exploits and experiences—recorded by Brigham Young’s 1847 vanguard company, the ten pioneer companies that immediately followed, and the handcart companies of the 1850s—are generally well known to Latter-day Saints. Most of the popular retellings are limited, though, to individuals and companies who crossed the plains prior to the Civil War.

As historian Robert Huhn Jones has observed, “Few historians have focused on the plight of the overland roads during the Civil War or the impact of the war on the area they crossed.”[1] Most Civil War histories naturally concentrate on the war east of the Mississippi River and pay scant attention to the West. This essay, on the other hand, focuses on the security and maintenance during the American Civil War of the Mormon Trail between Salt Lake City and Independence Rock in present-day south-central Wyoming.[2]

When Confederate artillery, under the command of P. G. T. Beauregard, fired on Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor during April 1861, America changed forever. Initially, Utah Territory was as isolated from that event as anywhere on the continent could be. The war seemed like a problem for the rest of the country, but not Utah. Tabernacle sermons and journals alike thanked God for the removal of the Church to the safety of the West. It did not take long, though, for the war to affect Utah as well.

Utah Territory before the Civil War

After arriving in the Salt Lake Valley in July 1847 (which was then part of Mexico), the Latter-day Saints enjoyed a decade of relative peace and quiet. During the popularly named Utah War (1857–58), President James Buchanan sent a significant portion of the U.S. Army to quell a Mormon rebellion he believed was occurring in Utah.[3] In the immediate aftermath of the Utah War, almost one-fourth of the U.S. Army was deployed in Utah Territory—with the majority of the soldiers stationed at Camp Floyd, forty miles southwest of Salt Lake City.[4] Although unplanned, the proximity of the Utah War to Southern secession meant that Utah played a consequential role in the nation’s military preparations for the Civil War. Utah was the army’s last major deployment prior to the war and served, in hindsight, as a proving ground for tactics, training, weaponry, and logistics.[5] Many Civil War commanders and soldiers—Union and Confederate—received their last military field training in Utah shortly before the outbreak of the war.

Utah’s unique relationship to the Civil War was influenced by both geography and politics. The boundaries originally proposed in 1849 for the State of Deseret were substantially reduced on September 9, 1850, when the Territory of Utah was created as part of the Compromise of 1850. At the beginning of the Civil War, Utah’s borders included all of present-day Utah, most of Nevada, and parts of Wyoming and Colorado.[6] During the four years of the Civil War, 1861 to 1865, Utah’s boundaries were reduced on three separate occasions. Utah’s eastern border was adjusted in February 1861, when the Colorado Territory was created. In March of that year the Nevada Territory was established, and the Nebraska Territory was given the northeastern portion of Utah Territory (currently part of southern Wyoming). In July 1862, less than one week after President Abraham Lincoln signed the Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act (the first American antipolygamy legislation), an additional portion of Utah Territory west of the thirty-eighth degree of longitude was transferred to Nevada.[7]

Utah’s political situation in the 1860s was as volatile as its borders. During the course of the Civil War, Utah had four territorial governors and several acting governors (who served while the territory awaited the arrival of the next presidential gubernatorial appointee). Alfred Cumming, a Southerner who was placed at Utah’s helm by President James Buchanan near the end of the Utah War, served as territorial governor until he made a quick departure on May 17, 1861. Francis (Frank) Wootton served in Cumming’s absence. When Cumming was asked how Wootton would get along as acting governor, Cumming reportedly replied, “Get along? Well enough, if he will do nothing. There is nothing to do. Alfred Cumming is governor of the Territory, but Brigham Young is Governor of the people. By ——, I am not fool enough to think otherwise. Let Wootton learn that, and he will get along, and the sooner he knows that the better. This is a curious place.”[8]

John W. Dawson, President Abraham Lincoln’s political appointee to replace Cumming as governor, was a “political chameleon,” having been a Whig, a Democrat, a Know-Nothing, an American Party member, and a Republican prior to his appointment as Utah’s territorial governor.[9] Dawson actually served as governor for only three weeks (from December 7 to 31, 1861); he fled the state after being accused “of making indecent proposals to Mormon women, one of whom drove him from her home with a fire shovel.” The first night of his return trip to the East, he was “set upon” and “robbed, kicked and beaten quite severely.” As historian E. B. Long noted, “The circumstances of the whole episode are cloudy and the stories vary.”[10] Frank Fuller, Utah’s territorial secretary, served as acting governor twice—first between Acting Governor Wootton and Governor Dawson and again after Governor Dawson fled the state until Stephen S. Harding arrived in July 1862. Harding was removed from office after serving just eleven months. He was replaced in June 1863 by James Duane Doty, who had previously served as the superintendent of Indian Affairs for Utah Territory. Doty died in office on June 13, 1865—just ten days before the last Confederate commander, Brigadier General Stand Watie, a Cherokee Indian, surrendered in present-day Oklahoma.[11]

Why did Washington care about keeping the trail open and safe during the Civil War? No formal list of reasons was ever articulated during the war, but from a national perspective, the continued flow of communication—by both telegraph and mail—was of paramount importance. The telegraph, which generally ran adjacent to emigrant trails, revolutionized long-distance communication within the nation. The eastern telegraph line from Omaha reached Salt Lake City on October 18, 1861; the western line from Carson City arrived on October 24. Suddenly, it took minutes rather than weeks or months for news to travel across the nation. A considerable amount of mail also traveled on the trail each year. When the trail was not safe, mail and telegraph traffic were both in jeopardy.

A second federal concern involved the possible threat of secession in the West. California, which received statehood in 1850, was a source of needed revenue, and the federal government was anxious to keep it firmly in the Union. If any territory between California and Colorado seceded and joined the Confederacy, it would have created a problem for Washington. Shortly after the telegraph began operation in Utah, Brigham Young sent one of the earliest messages from Salt Lake City: “Utah has not seceded, but is firm for the Constitution and laws of our once happy country.”[12] Finally, and probably last on the list of federal priorities regarding the trail, was the continuing western emigration of settlers. Tens of thousands of settlers, Mormons and non-Mormons, emigrated west throughout the Civil War, many of them trying to flee the war. Enabling and supporting that emigration, though, was not a top government priority; the federal government was facing much larger problems.

Brigham Young and the Latter-day Saints would certainly have ordered their list of priorities differently. From Utah’s perspective, emigration would probably have topped the list, followed closely by mail and telegraph communication. The potential threat posed by secession was not taken seriously, and Latter-day Saints had little desire or interest in the return of Union soldiers.

Responsibility for the security and maintenance of the Mormon Trail that linked “the States” to Utah Territory changed hands four times during the Civil War. In the first period, which lasted from the beginning of the war until the fall of 1861, the trail was the responsibility of the U.S. Army. Throughout the second period, from fall 1861 until spring 1862, seemingly no one was responsible for security and maintenance on the trail. That brief period of anarchy gave way (between April and August 1862) to the third period, a short interlude when Latter-day Saints took an active role guarding and maintaining the trail. And the fourth period—which was the longest as well as the last—extended from fall 1862 until the end of the war, when the trail was once again the responsibility of the U.S. Army. The remainder of this essay will take a closer look at trail responsibility during the Civil War.[13]

The Army Is Responsible (Spring–Fall 1861)

Beginning in June 1858, when the U.S. Army marched through Salt Lake City on their way to establish Camp Floyd, the trail was secured and improved by federal military forces. When South Carolina seceded in December 1860, Camp Floyd was commanded by Colonel Philip St. George Cooke.[14] The camp was soon renamed Fort Crittenden—honoring John J. Crittenden, a U.S. senator, former U.S. representative, and former governor of Kentucky—following the Southern defection of John B. Floyd (President James Buchanan’s secretary of war after whom the camp was originally named). The army was still responsible for security on the trails when the Civil War began. Soldiers stationed in Utah Territory had rebuilt and occupied Fort Bridger as well as other camps and stations along the trail.

By May 1861, hostile actions on the emigrant trails—by both Indians[15] and whites—caused Utah’s governor, Alfred Cumming, to request that a detachment of soldiers from Fort Crittenden be sent to guard the Overland Trail “for the protection of the Mail, Express, and emigrants, and, if need be, for the chastisement of the Indians.”[16] Soldiers were not sent at that time but were instead ordered by the War Department to leave Utah and join the growing conflict in the East. In June, the New York Times reported that Utah’s governor felt that removing the soldiers “would leave the inhabitants too much exposed to attacks from unfriendly Indians.”[17]

Anarchy on the Trail (Fall 1861–Spring 1862)

As secession spread across the Southern states, the War Department recognized that hundreds of loyal soldiers were stationed in Utah and unable to directly participate in the war. On May 17, 1861, not long after shots were fired at Fort Sumter, Colonel Cooke received orders to return to the East with his entire command.[18] During the summer of 1861, the army closed Fort Crittenden, sold everything they could not take with them, and departed Utah.[19] Indians operating on the trail became increasingly brazen, stealing and pillaging—so much so that even as the army departed, Indians “helped themselves to a goodly toll of Army cattle.”[20] As the soldiers marched east, they passed Mormon emigrants who were heading west.[21] Brigham Young and Church leaders were pleased when the army announced its departure and saw the exodus as a positive development. They were sorry, of course, that the war was occurring, but, quite frankly, they were not sorry that the war created conditions for the army’s removal—leaving them alone once again in their mountain retreat.

The War Department recognized that the withdrawal of the army would leave the Overland Trail exposed. On July 24, 1861, Secretary of War Simon Cameron accepted from California’s governor, John G. Downey, “for three years[,] one regiment of infantry and five companies [of] cavalry to guard the Overland Mail Route from Carson Valley to Salt Lake.”[22] None of those soldiers were sent to Utah Territory at that time.

After the withdrawal of the army, Indians quickly recognized that the soldiers were gone. During the fall of 1861 and into the winter of 1862, there were no longer hundreds of soldiers patrolling the trails, maintaining the telegraph stations, and keeping the mail safe and moving; hostile Indian actions flared up across the region. As the historian Ray Colton observed, “Intelligent Indians saw in the Civil War the opportunity, while the whites were killing one another, to drive the intruders out of the land of their fathers or exterminate them.”[23] There were frequent reports of Indian attacks in the Deseret News, and travel on the trail became increasingly dangerous.[24] Telegraph and mail stations were destroyed, stagecoaches and emigrants were attacked, and mail was scattered and burned by Ute, Shoshone, Kiowa, Bannock, and Cheyenne Indians (who tended to be equestrian). Non-equestrian Indian tribes, such as the Paiutes and Goshutes, were less inclined to violence against soldiers and settlers.[25]

Utah’s territorial militia, the Nauvoo Legion, had operated in a reduced posture following the peaceful resolution of the Utah War. After news of the attack on Fort Sumter reached Utah, Brigham Young directed Daniel H. Wells—who served not only as commanding general of the Nauvoo Legion in Utah but also as his counselor in the Church’s First Presidency—to revitalize and reorganize the legion so that it could respond quickly if called upon to provide soldiers to fight in the Civil War. The reorganization was completed in early 1862, but no actions were taken then to secure the emigrant trails.[26]

Latter-day Saints Guard the Trail (April–August 1862)

General James H. Craig, brigadier general of volunteers, received orders on April 16, 1862, making him responsible for protecting the entire Overland Trail,[27] but he received too few soldiers to adequately maintain security along the trail. By spring 1862, increasingly aggressive Indian actions made travel on the trail difficult and dangerous. Mail and telegraph communication was regularly interrupted. In mid-April, William Hooper (a former Utah Territory delegate to the U.S. Congress who was charged with carrying Utah’s latest statehood request to Washington) and Chauncey W. West (who had been called to serve as a Mormon missionary in England) needed to travel east, but it was too dangerous for them to travel alone.[28] Hooper and Frank Fuller, the territorial secretary who was serving as acting governor (because Utah’s previous governor, John W. Dawson—a newspaper editor from Indiana who had supported Lincoln in the 1860 election—had fled Utah on New Year’s Eve 1861), contacted the Overland Mail Company “to see if they [would] send an escort” to accompany travelers and the mail heading east, but the mail company “decline[d] to have anything to do with it.”[29]

Earlier in April, Major J. E. Eaton, superintendent of the Overland Mail Company, requested assistance from Utah Territory in securing the trail. On April 25, acting governor Frank Fuller issued a call to General Daniel H. Wells for “twenty mounted men duly offered and properly armed and equipped, carrying sufficient ammunition for thirty days’ service in the field” for the purpose of providing “military protection of mails, passengers, and the property of the mail company from the depredations of hostile Indians.” Fuller also requested that the militiamen protect “the persons of passengers” as well.[30] The acting governor further directed that the “officer commanding this expedition will use his discretion as to the movements of his command, as well as the term of service necessary to insure the safety and security of the mail and all persons and property connected therewith, and will communicate freely by telegraph when necessary.”[31] Colonel Robert T. Burton (commander of the First Cavalry Regiment of the Nauvoo Legion and a Salt Lake County sheriff), twenty militiamen, and four teamsters answered the call.[32] The Sacramento Daily Union reported that “the company is composed of picked men, the cream of the regiment that could be spared. . . . Brigham [Young] has sent two of his own sons and a son-in-law, and Heber [C. Kimball] has two of his sons in it.”[33] Burton’s detachment left Salt Lake City the following day.

A small anecdote about Robert Burton’s horse is worth sharing, as his horse was widely renowned for demonstrating extraordinary intelligence. According to William Burton, Robert’s son, one night on the trail east of Fort Bridger “between one and two o’clock in the morning the Colonel was instantly awakened. He thought at first that his horse was grazing on his hair, but he immediately discovered the reason for this unusual browsing. The warning came just in time to save him. An Indian stood at his side with deadly intent. Burton sprang to his feet and shouted, ‘Indians!’ The troops sprang up and several fired at the Indian as he made his escape.”[34] Burton and his soldiers served on the trail from April through the end of May 1862—contending with bad weather, rebuilding mail stations, gathering scattered mail, and repairing roads.[35]

On April 28, 1862, just two days after Colonel Burton’s detachment left Salt Lake City, Brigham Young received a telegram from General Lorenzo Thomas, the U.S. Army’s adjutant general, requesting that he raise a cavalry company of active-duty soldiers from Utah for ninety days’ service on the trail:

Washington, April 28, 1862

Mr. Brigham Young,

Salt Lake City, Utah:

By express direction of the President of the United States you are hereby authorized to raise, arm, and equip one company of cavalry for ninety days’ service. This company will be organized as follows: One captain, 1 first lieutenant, 1 second lieutenant, 1 first sergeant, 1 quartermaster-sergeant, 4 sergeants, 8 corporals, 2 musicians, 2 farriers, 1 saddler, 1 wagoner, and from 56 to 72 privates. The company will be employed to protect the property of the telegraph and overland mail companies in or about Independence Rock, where depredations have been committed, and will be continued in service only till the U.S. troops can reach the point where they are so much needed. It may therefore be disbanded previous to the expiration of the ninety days. It will not be employed for any offensive operations other than may grow out of the duty hereinbefore assigned to it. The officers of the company will be mustered into the U.S. service by any civil officer of the United States Government at Salt Lake City competent to administer the oath. The men will then be enlisted by the company officers. The men employed in the service above named will be entitled to receive no other than the allowances authorized by law to soldiers in the service of the United States. Until the proper staff officer for subsisting these men arrive you will please furnish subsistence for them yourself, keeping an accurate account thereof for future settlement with the United States Government.

By order of the Secretary of War:

L. Thomas, Adjutant-General.[36]

There is some uncertainty regarding who conceived the idea of raising a cavalry company from Utah. In December 1861, Brigham Young notified John M. Bernhisel, Utah’s territorial delegate to Congress, that “we are ready to furnish a home guard for the protection of the telegraph and mail lines and overland travel within our boundaries, upon such terms as other volunteer companies employed by the Government.”[37] On April 11, 1862, Frank Fuller (acting governor), J. F. Kinney (Utah Supreme Court chief justice), Edward R. Fox (Utah surveyor general), and officials from the Overland Mail Company and Pacific Telegraph Company appealed directly to Edwin M. Stanton, President Lincoln’s secretary of war, for assistance in controlling the Indians in Utah who were robbing and destroying Overland Mail Company stations and killing cattle. They asked Secretary Stanton to “put in service” under the command of James D. Doty, Utah’s superintendent of Indian affairs, “a regiment [of] mounted rangers from inhabitants of the Territory.”[38] After learning of the request to Secretary Stanton, Brigham Young wrote on April 14 to John Bernhisel, Utah’s delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives, that “the militia of Utah are ready and able as they ever have been, to take care of all the Indians within our borders, and are able and willing to protect the mail lines, if called upon to do so.”[39]

Ben Holladay, proprietor of the U.S. mail and stage lines that extended from St. Joseph to San Francisco, had also been working behind the scenes with Secretary Stanton and others, including Senator Milton S. Latham from California, to convince President Lincoln to call for a Mormon unit to provide security on the trail because they recognized there were not enough Union soldiers to do so. In an April 1862 letter to Lincoln, Latham suggested that any request to provide soldiers to guard the trail should be sent to Brigham Young.[40]

An April 24 army report “on measures taken to make secure the Overland Mail Route to California” signed by General Lorenzo Thomas, the army’s adjutant general, suggested that extending a request to Brigham Young for soldiers offered “the most expeditious and economical remedy” for raising a military unit from Utah because of Young’s “known influence over his own people, and over the Indian tribes” in the region. Thomas’s letter acknowledged that Brigham Young was “not a functionary recognized by the United States Government” but still “respectfully submitted” that any request should be made directly to him.[41] Lincoln was apparently convinced and authorized the War Department to send the April 28 telegram requesting military support to Brigham Young (and not to the acting governor, Frank Fuller).

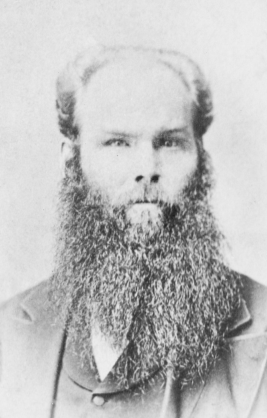

Lot Smith. Courtesy of Church History Library.

Lot Smith. Courtesy of Church History Library.

At 9:00 p.m., “within the hour” from having received the War Department’s April 28 telegram,[42] Brigham Young dictated a letter to his counselor, Daniel H. Wells. While doing so, President Young was probably experiencing a great deal of pain because earlier that day John L. Dunyon, surgeon general of the Nauvoo Legion, had pulled the last five teeth in his mouth.[43] Addressing his letter to “Lieut. General Daniel H. Wells, Commanding the Militia,” President Young directed Wells “in accordance with the express direction of the President of the United States” to “forthwith muster said company into the service of the United States” so that they could get “started at once for the destination and service required.”[44]

General Wells could have selected Colonel Robert T. Burton to command the Utah cavalry company. Burton was already on the trail escorting Hooper and West and was only twenty-five miles outside of Salt Lake City. Instead, Wells chose to give the assignment to Lot Smith, who had an interesting military pedigree. As the youngest member of the Mormon Battalion, Smith had actively disrupted, harassed, and burned army supply trains during the Utah War and was then serving as one of Colonel Robert T. Burton’s battalion commanders in the Nauvoo Legion, Utah’s territorial militia. Although serving as a militia major, Smith was commissioned as an active-duty army captain when he assumed command of his cavalry company.[45] The Lot Smith Utah Cavalry Company was raised—with local men and often borrowed animals—in less than two days.[46] Brigham Young waited until the company had been mustered before he sent this response to General Thomas:

Salt Lake City, April 30, 1862

Adjutant General Thomas, U. S. A. Washington, D. C.

Upon receipt of your telegram of April 27, I requested General Daniel H. Wells, of the Utah militia to proceed at once to raise a company of cavalry and equip and muster them into the service of the United States army for ninety days, as per your telegram. General Wells, forthwith issued the necessary orders and on the 29th day of April the commissioned officers and non-commissioned officers and privates, including teamsters, were sworn in by Chief Justice John F. Kinney, and the company went into camp adjacent to the city the same day.

Brigham Young[47]

That same day, in a letter to the Lot Smith Cavalry Company, the First Presidency directed the soldiers to “recognize the hand of Providence in [the Saints’] behalf” and to act as emissaries of the Church, to “establish the influence God has given us.” They were to “be kind, forbearing, and righteous in all [their] acts and sayings in public and private . . . that [they] may greet you with pleasure as those who have faithfully performed a work worthy of great praise.” Doing so would enable the men to “again prove that noble hearted American citizens can don arms in the defense of right and justice, without descending one hair’s breadth below the high standard of American manhood.” Counsel was also given to abstain from “card playing, dicing, gambling, drinking intoxicating liquors, or swearing” and to “be kind to [their] animals.” Expectations were expressed that the company would “improve the road as you pass along, so much so as practicable diligence in reaching your destination will warrant, not only for your own convenience but more particularly for the accommodation of the Mail Company and general travel,” showing the First Presidency’s concern for cross-country communication and continued Mormon emigration. The company was further directed that “morning and evening of each day let prayer be publicly offered in the Command and in all detachments thereof, that you may constantly enjoy the guidance and protecting care of Israel’s God and be blest in the performance of every duty devolved upon you.”[48]

The Lot Smith Cavalry Company—with just over one hundred soldiers and teamsters—departed Salt Lake City during the afternoon of May 1. Deep snow in the mountains made travel tedious, and they made little headway. The following day, Brigham Young and Daniel H. Wells traveled up the canyon and spoke with the soldiers. In what is sometimes referred to as the Canyon Discourse, President Young counseled the men to remember that “although you are United States soldiers you are still members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and while you have sworn allegiance to the constitution and government of our country, and we have vowed to preserve the Union, the best way to accomplish this high purpose is to shun all evil. . . . Remember your prayers . . . establish peace with the Indians . . . [and] always give ready obedience to the orders of your commanding officers.” He then promised them that “if you will do this I promise you, as a servant of the Lord, that not one of you shall fall by the hand of an enemy.”[49] A nineteen-year-old private by the name of McNicol later drowned while crossing the Snake River, but as President Young had promised, no soldiers died in combat.[50]

Speaking of the challenges that faced the Lot Smith Cavalry Company as they traveled east, Harvey C. Hullinger, a private who served as the company’s doctor and a self-appointed diarist, was quoted as noting that “only the Latter-day Saints could have surmounted these difficulties and remained cheerful.”[51] Near Independence Rock (which was outside Utah Territory),[52] after crossing much of what is today southwest and south-central Wyoming, the Lot Smith Company reported to Lieutenant Colonel William O. Collins, commander of the Eleventh Ohio Cavalry.[53] A contemporary described Collins as “a very fine old gentleman, rather old for military service, but finely preserved, energetic and soldierly.” Fort Collins, Colorado, was named for him.[54] The Eleventh Ohio and Lot Smith Cavalry Company were jointly charged with protecting the Overland Trail and keeping peace with the Indians on the plains.[55] Smith received orders “to guard the mail route and telegraph line from Green River to Salt Lake City, a distance of about two hundred miles.”[56]

On May 21, 1862, at “Mr. Marchant’s Station at Devil’s Gate” the Burton detachment and the Lot Smith Cavalry Company reportedly met and shared trail information.[57] Throughout the remainder of their service, the Lot Smith Cavalry Company rebuilt telegraph stations, recovered stolen horses and property, built and rebuilt bridges, and provided a military presence on the trail. The company was mustered out at Salt Lake City in mid-August.

The Army Is Again Responsible (Fall 1862 until the War’s End)

The War Department offered to extend the Lot Smith Cavalry Company’s military service shortly after they were released from active duty. On August 25, Secretary Stanton authorized General James Craig to “raise 100 mounted men in the mountains and re-enlist the Utah troops for three months,”[58] but Brigham Young declined because he had learned that the U.S. Army was returning to Utah. Young defiantly declared that “if the Government of the United States should now ask for a battalion of men to fight in the present battle-fields of the nation, while there is a camp of soldiers from abroad located within the corporate limits of this city, I would not ask one man to go; I would see them in hell first.”[59] Stephen S. Harding, Utah’s new governor, informed Washington simply that “things are not right.”[60] Referring to the fact that soldiers would soon be garrisoned again in Utah, a New York Times reporter suggested that it was “much more likely that these Gentile Soldiers from California will create difficulties in Utah than that they will ever settle them. If the troops are designed to operate against the fragments of dying savages west of the Rocky Mountains, we are likely to have an Indian war on our hands this Summer, which, though barren enough of value, will be fertile enough of expenses.”[61]

Frank Thomas, Lot’s One Hundred. This painting is a representation of the Lot Smith Cavalry Company in Echo Canyon on May 1, 1862, at the beginning of their military service. Courtesy of Frank Thomas.

Frank Thomas, Lot’s One Hundred. This painting is a representation of the Lot Smith Cavalry Company in Echo Canyon on May 1, 1862, at the beginning of their military service. Courtesy of Frank Thomas.

Several regiments of California Volunteers commanded by Colonel Patrick Edward Connor arrived in Utah Territory during October 1862. Earlier that fall, Connor traveled to Utah in civilian clothing and decided not to reoccupy Fort Crittenden; he opted, instead, to build a new fort in the foothills overlooking Salt Lake City “on an elevated spot which commands a full view of the city.”[62] Established on October 26, 1862, and named after the late senator Stephen A. Douglas, Camp Douglas (later renamed Fort Douglas in 1878) headquartered the Union military presence in Utah Territory throughout the remainder of the Civil War and into the decades that followed. History does not record that Patrick Connor and Brigham Young ever met face to face, but they had a deep and continuing distrust and apparent dislike for each other.

At the beginning of December 1862, Colonel Connor notified the army’s Department of the Pacific in San Francisco that “Indians are threatening the Overland Mail Route east and west of here . . . and fears are entertained that they will attack some of the stations of the Overland Mail.”[63] On January 29, 1863, soldiers under the personal command of Colonel Connor marched to the Bear River in southern Idaho (near Preston) and attacked a large Indian camp. Connor declared in his battle report that “it was not my intention to take any prisoners.”[64] As historian Harold Schindler succinctly summarized, “Bear River began as a battle, but it most certainly degenerated into a massacre”[65]—one of the largest Indian massacres in American history. Nineteen soldiers and more than 250 Indian men, women, and children were killed—the exact number of Indian deaths is unknown. The Deseret News reported that “Col. Connor and the Volunteers who went north last week to look after the Indians on the Bear River have, in a very short space of time, done a larger amount of Indian killing than ever fell to the lot of any single expedition of which we have any knowledge.”[66] General Henry W. Halleck, the general-in-chief of the U.S. Army who was widely known by his nickname, “Old Brains,” wrote to Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton “with the recommendation that Colonel Connor be made a brigadier-general for the heroic conduct of himself and his men in the battle of Bear River.”[67] For his heavy-handed approach to quieting the Indian population, Connor was promoted, and his attack at Bear River was viewed by the War Department as a great military victory.[68] Within a year, Connor had the reputation in some circles “of being the greatest Indian-fighter on the continent.”[69] As the end of the war approached, Connor’s forces were supplemented by several units of Galvanized Yankees—former Confederate soldiers who were captured and later “accepted the blue uniform of the United States Army in exchange for freedom from prison.”[70] A series of treaties were signed in rapid succession with Indian tribes in Utah Territory following the Bear River massacre.[71] Indian attacks on the trail generally subsided, and the trail became safer. Connor’s actions brought the results he desired. An August 1865 army report noted that “the mail road and telegraph [are] all quiet.”[72]

Conclusion

The security and maintenance of the Mormon Trail during the Civil War was important to the Latter-day Saints. As a result of the combined efforts of the United States Army and Latter-day Saints to keep the Mormon Trail open during the war, Mormon emigration continued throughout the entire war. Approximately seventeen thousand Latter-day Saints crossed the plains during the Civil War—which is about half the total immigration to Utah that occurred between 1847 and 1860.[73] Although Utah Territory was asked to provide only one active duty military unit during the war, the service of the Lot Smith Cavalry Company provided Utah with an opportunity to actively demonstrate its loyalty to the Union. The Saints served well when they were called, and the Civil War helped Utah become more integrated into the nation.

Notes

[1] Robert Huhn Jones, Guarding the Overland Trails: The Eleventh Ohio Cavalry in the Civil War (Spokane, WA: Arthur H. Clark, 2005), 21.

[2] Previous scholarship has broadly addressed the Civil War in the West but has not looked specifically at the Mormon Trail during the war. See, for example, Ray C. Colton, The Civil War in the Western Territories: Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Utah (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1959); Captain Eugene F. Ware, The Indian War of 1864 (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1960); E. B. Long, The Saints and the Union: Utah Territory during the Civil War (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1981); Dee Brown, The Galvanized Yankees (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1963); and Alvin M. Josephy Jr., The Civil War in the American West (New York: Vintage Press, 1993).

[3] See, William P. MacKinnon, ed., At Sword’s Point, Part I: A Documentary History of the Utah War to 1858, vol. 10 of Kingdom in the West: The Mormons and the American Frontier (Norman: Arthur H. Clark, 2008). At Sword’s Point, Part II, is forthcoming. See also Leroy Hafen, Utah Expedition, 1857–1858: A Documentary Account, 2nd ed. (Norman, OK: Arthur H. Clark, 1983); and David L. Bigler and Will Bagley, The Mormon Rebellion: America’s First Civil War, 1857–1858 (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2011).

[4] Salt Lake City was officially named Great Salt Lake City until 1868 but will be referred to as Salt Lake City throughout this essay. The percentage of the U.S. Army that was stationed in Utah gradually decreased between summer 1858 and summer 1861. On June 30, 1861, Colonel Philip St. George Cooke, commanding the Department of Utah, reported 604 soldiers “present and absent” within his department—a total surely affected by individual desertions to the Confederacy. See “Consolidated abstract from returns of the U.S. Army on or about June 30, 1861,” in War of the Rebellion: A Compilation of the Official Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, 130 vols. (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1880–1901), series 3, vol. 1, 301–10 (hereafter referred to as O.R.).

[5] See William P. MacKinnon, “Prelude to Civil War: The Utah War’s Impact and Legacy,” in Civil War Saints, ed. Kenneth L. Alford (Provo, UT: Religious Studies Center; Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2012), 1–21.

[6] Utah’s borders were, generally, (a) the forty-second parallel on the north, (b) the state of California on the west, (c) the thirty-seventh parallel on the south, and (d) southern Wyoming and western Colorado on the east.

[7] Two additional boundary changes occurred in the years immediately following the Civil War. In May 1866 Nevada received additional land from Utah when Nevada became a state. Utah’s last boundary change took place in July 1868 when Wyoming Territory was created and Congress transferred Wyoming’s southwest corner from Utah to Wyoming. Andrew Love Neff, History of Utah: 1847 to 1869 (Salt Lake City: Deseret News Press, 1940), 691, 709.

[8] Orson F. Whitney, History of Utah, (Salt Lake City: Cannon and Sons, 1893), 2:38.

[9] Long, Saints and the Union, 39.

[10] Long, Saints and the Union, 46, 48.

[11] Colton, Civil War in the Western Territories, 182–89. W. P. Adair and James M. Bell to Brig. Gen. J. C. Veatch, July 19, 1865, in O.R., series 1, vol. 58, part 2, 1099–1101. In the surrender document, Watie is referred to as “Brigadier-General Stand Watie, governor and principal chief of that part of the Cherokee Nation lately allied with the Confederate States in acts of hostility against the Government of the United States.” Watie surrendered at Doaksville in the Choctaw Indian Nation.

[12] The message was sent to J. H. Wade, president of the Pacific Telegraph Company in Cleveland, Ohio. “The Completion of the Telegraph,” Deseret News, October 23, 1861, 5.

[13] Unless otherwise stated, references within this essay to “the trail” refer to the portion of the Mormon Trail that ran through Utah Territory and present-day Wyoming.

[14] Cooke was an 1827 graduate of the United States Military Academy at West Point (Cullum number 492). See Michael J. Krisman, ed., Register of Graduates and Former Cadets of the United States Military Academy (Chicago: R. R. Donnelley and Sons, 1980), 223. “A native of Virginia, Cooke (not to be confused with the similarly-named and fellow Virginian Philip St. George Cocke—who served the Confederacy as a brigadier general) had ties to Mormons that stretched back to his service with the Mormon Battalion in the 1840s during the Mexican War. Cooke’s southern roots and secessionist family members—J. E. B. Stuart, the famous Confederate cavalry commander, was Cooke’s son-in-law, and his own son, John Rogers Cooke, fought in the Army of Northern Virginia as an infantry brigade commander—caused some concern within the army, but Colonel Cooke declared his loyalty to the Union and earned the rank of brevet major general by the war’s end. Under Cooke’s command, Indian policy in Utah Territory had primarily been the domain of Utah’s frequently changing Indian superintendents and agents. That would change the following year with the arrival of Colonel Patrick Edward Connor and his California volunteers.” Kenneth L. Alford, “Indian Relations in Utah during the Civil War,” in Civil War Saints, 211.

[15] While current usage often favors the term Native Americans or Native peoples, this essay will use the term Indians to conform to common nineteenth-century usage. See, for example, William P. Dole to O. H. Irish, “Utah Superintendency,” March 28, 1865, in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, Accompanying the Annual Report of the Secretary of the Interior for the Year 1865 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1865), 148–49

[16] “Affairs in Utah,” New York Times, June 2, 1861, 2. “Affairs in Utah,” New York Times, June 17, 1861, 5. Whitney noted that “White men took part in these depredations,” and Vetterli suggested the whites involved may have been Southerners who sought to disrupt relations between Washington and the West. Orson F. Whitney, The Making of the State: A School History of Utah (Salt Lake City: Deseret News, 1908), 132; Richard Vetterli, Mormonism, Americanism and Politics (Salt Lake City: Ensign Publications, 1961), 519.

[17] “News of the Day,” New York Times, June 24, 1861, 4.

[18] Long, Saints and the Union, 7.

[19] With the exception of seventeen soldiers left behind to manage affairs at Fort Bridger, Colonel Philip St. George Cooke’s entire command of “ten companies of Infantry Artillery and Dragoons” marched east out of Utah Territory on August 9, 1861. P. St. Geo. Cooke to Bvt Brgr. Genl. L. Thomas, August 9, 1861, “Letters Received by the Office of the Adjutant General (Main Series), 1861–70,” National Archives, RG94, M619, Roll 65. For a list of Fort Bridger’s commanders during the interim period between the August 1861 departure and October 1862 return of federal forces to Utah, see Robert S. Ellison, Fort Bridger, Wyoming: A Brief History (Casper, WY: The Historical Landmark Commission of Wyoming, 1931), 59.

[20] “Affairs in Utah,” New York Times, August 24, 1861, 5.

[21] William G. Hartley, “Latter-day Saint Emigration during the Civil War,” in Civil War Saints, 244.

[22] Simon Cameron to Governor of California, July 24, 1861, in O.R., series 1, vol. 50, part 1, 543.

[23] Colton, Civil War in the Western Territories, 121.

[24] See Alford, “Indian Relations in Utah,” 203–25.

[25] Ned Blackhawk, Violence Over the Land: Indians and Empires in the Early American West (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2006), 231; Colton, Civil War in the Western Territories, 166, 170.

[26] See Ephriam D. Dickson III, “Protecting the Home Front: The Utah Territorial Militia during the Civil War,” in Civil War Saints, 143–60.

[27] Gen. S. D. Sturgis to Headquarters District of Kansas, April 16, 1862, in O.R., series 1, vol. 13, 362.

[28] Brigham Young to Pres. George Q. Cannon, April 15, 1862, Brigham Young Letterpress Copybooks, Church History Library, Salt Lake City, 209–11.

[29] History of Brigham Young, April 25, 1862, CR 100 102, Church History Library; Long, Saints and the Union, 39.

[30] Margaret M. Fisher, Utah and the Civil War: Being the Story of the Part Played by the People of Utah in that Great Conflict, with Special Reference to the Lot Smith Expedition and the Robert T. Burton Expedition (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 1929), 112.

[31] Fisher, Utah and the Civil War, 112.

[32] Fisher, Utah and the Civil War, 113. An April 25, 1862, entry in History of Brigham Young refers to Burton’s unit as a posse. Burton led an interesting and varied life. He was part of the party that rescued the Martin handcart company in 1856, served in the Nauvoo Legion during the Utah War, led militia forces against the Morrisites near Ogden, and served as a member of the Presiding Bishopric for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints from 1874 until his death in 1907. For additional information, see Janet Burton Seegmiller, Be Kind to the Poor: The Life Story of Robert Taylor Burton (n.p.: Robert Taylor Burton Family Organization, 1988).

[33] “Letter from Salt Lake,” Sacramento Daily Union, May 9, 1862, 1. Brigham Young Jr. served as the unit’s adjutant.

[34] Fisher, Utah and the Civil War, 113.

[35] Shortly after returning home, Burton was named as one of the three “Marshalls of the Day” for the 1862 Fourth of July celebration in Salt Lake City and then successfully ran for re-election as sheriff of Great Salt Lake County on the “People’s Ticket.” “Eighty-Sixth Anniversary,” Deseret News, July 2, 1862, 4; “Annual Election—1862,” Deseret News, July 30, 1862, 4.

[36] L. Thomas to Mr. Brigham Young, April 28, 1862, in O.R., series 3, vol. 2, 27.

[37] Brigham Young to John Bernhisel, December 30, 1861, Brigham Young Letterpress Copybooks.

[38] Frank Fuller, I. F. Kinney, Edward R. Fox, Frederick Cook, H. S. R. Rowe, E. R. Purple, Joseph Holladay, and W. B. Hibbad to Edwin M. Stanton, April 11, 1862, in Report of the Commissioner of Indian Affairs for the Year 1862 (Washington, DC: Government Printing Office, 1863), 212.

[39] Brigham Young to Hon. John M. Bernhisel, April 14, 1862, Brigham Young Letter Books, Church History Library. Historian E. B. Long states that Young wired his message to Bernhisel, which is logical, but nothing in the Brigham Young Letterpress Copybooks confirms that the signed letter was actually telegraphed and not mailed. Long, Saints and the Union, 82.

[40] Abraham Lincoln, endorsement, April 26, 1862, in New Letters and Papers of Lincoln, comp. Paul M. Angle (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1930), 291–92.

[41] General Lorenzo Thomas to General Denver, April 24, 1862, in O.R., series 1, vol. 50, part 1, 1023–24.

[42] This quotation is found in Edward W. Tullidge, History of Salt Lake City: by Authority of the City Council and under the Supervision of a Committee Appointed by the Council and Author (Salt Lake City: Star Printing, 1886), 255.

[43] History of Brigham Young, April 28, 1862. After mentioning the teeth extractions, the History of Brigham Young states that “the President is getting a new set of teeth made by Sec’y Frank Fuller.” Fuller, Utah’s acting governor, had practiced as a dentist in Massachusetts prior to becoming involved in politics. See also the Frank Fuller Papers, MS 0305, J. Willard Marriott Library, University of Utah.

[44] Brigham Young to Daniel H. Wells, April 28, 1862, Brigham Young Letterpress Copybooks.

[45] The fact that the Lot Smith Utah Cavalry Company served on active duty meant that soldiers in that unit became eligible for small government pensions after the war if they could prove a war-related injury or disability. Colonel Robert T. Burton and the Nauvoo Legion militiamen who served with him were not commissioned or enlisted by the federal government for the service they provided and did not qualify for either government pensions or as Civil War veterans.

[46] The three-month service provided by Lot Smith Cavalry Company was not unique. Other short-term cavalry units were formed in the West, such as the “hundred-day men,” who served with the Third Colorado Cavalry. Colton, Civil War in the Western Territories, 157.

[47] Quoted in Seymour B. Young, “Lest We Forget,” Improvement Era, March 1922, 336.

[48] First Presidency to Captain Lot Smith and Company, April 30, 1862, in Lot Smith Papers, Special Collections, Harold B. Lee Library, Brigham Young University.

[49] Fisher, Utah and the Civil War, 25–26.

[50] Fisher, Utah and the Civil War, 109.

[51] Fisher, Utah and the Civil War, 40.

[52] Independence Rock (42.49 latitude, 107.13 longitude) was so named because the prevailing view of pioneer company captains was that groups that reached Independence Rock prior to July 4 would arrive safely at their destination. Companies that reached Independence Rock later were in danger of being caught by cold and snow.

[53] David P. Robrock, “The Eleventh Ohio Volunteer Cavalry on the Central Plains, 1862–1866,” Arizona and the West 25, no. 1 (Spring 1983): 23.

[54] Lieutenant Colonel William Collin had a son, Caspar, who served as a lieutenant in his command. Caspar was killed in 1865 at the Battle of the Platte Bridge Station. “The town of Casper, in Wyoming, was named after the son.” Ware, Indian War of 1864, 120.

[55] Fisher, Utah and the Civil War, 26–27; see also J. H. Horton and Solomon Teverbaugh, A History of the Eleventh Regiment, (Ohio Volunteer Infantry) (Dayton, OH: W. J. Shuey, 1866), 72–88.

[56] Colton, Civil War in the Western Territories, 162.

[57] Fisher, Utah and the Civil War, 127.

[58] Governor Stephen Harding to Adjutant-General James Craig, August 25, 1862, in O.R., series 1, vol. 13, 596.

[59] Brigham Young, in Journal of Discourses (London: Latter-day Saints’ Book Depot, 1881), 10:107.

[60] Jas. Craig to Gen. Halleck, August 25, 1862, in O.R., series 3, vol. 2, 596.

[61] “A Needless War in Prospect,” New York Times, May 26, 1862, 4.

[62] P. Edw. Connor to Adjutant General, November 9, 1862, in O.R., series 1, vol. 50, part 2, 218.

[63] P. Edward Connor to Lt. Col. R. C. Drum, December 2, 1862, in O.R., series 1, vol. 50, part 1, 182.

[64] P. Edw. Connor to Lt. Col. R. C. Drum, February 6, 1863, in O.R., series 1, vol. 50, part 1, 187.

[65] Harold Schindler, “The Bear River Massacre: New Historical Evidence,” Utah Historical Quarterly 67, no. 4 (Fall 1999): 302. See also Ephriam D. Dickson III, “Addendum,” in Civil War Saints, 234–35.

[66] “The Fight with the Indians,” Deseret News, February 4, 1863, 5.

[67] H. W. Halleck to Edwin M. Stanton, March 29, 1863, in O.R., series 1, vol. 50, part 1, 185.

[68] Bear River is not the only Indian battle associated with the military career of General Patrick Edward Connor. Shortly after the end of the Civil War in August and September 1865, Connor commanded the Powder River Expedition against Sioux, Cheyenne, and Arapaho Indian tribes in present-day Wyoming and Montana. Approximately one hundred Indian men, women, and children were killed during the expedition. See H. D. Hampton, “The Powder River Expedition 1865,” Montana: The Magazine of Western History 14, no. 2 (1964): 2–15. Bear River is not the only Indian massacre that occurred in the West during the Civil War. At the Sand Creek Massacre (also known as Chivington’s Massacre) on November 29, 1864, hundreds of soldiers from the Colorado Territory militia attacked a friendly Cheyenne-Arapaho village and killed between 70 and 163 men, women, and children. See Colton, Civil War in the Western Territories, 157–59.

[69] Ware, Indian War of 1864, 310.

[70] Brown, Galvanized Yankees, 1.

[71] See Alford, “Indian Relations in Utah,” 218–20.

[72] Geo. F. Price to Maj. Gen. G. M. Dodge, August 15, 1865, in O.R., series 1, vol. 48, part 2, 1187–88.

[73] Hartley, “Latter-day Saint Emigration,” 261.